Abstract

Objective

To describe the association between postmenopausal estrogen therapy use and risk of ovarian carcinoma, specifically with regard to disease histotype and duration and timing of use.

Methods

We conducted a pooled analysis of 906 women with ovarian carcinoma and 1,220 controls; all 2,126 women included reported having had a hysterectomy. Ten population-based case-control studies participating in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC), an international consortium whose goal is to combine data from many studies with similar methods so reliable assessments of risk factors can be determined, were included. Self-reported questionnaire data from each study were harmonized and conditional logistic regression was used to examine estrogen therapy’s histotype-specific and duration and recency of use associations.

Results

Forty-three and a halfpercent of the controls reported previous use of estrogen therapy. Compared to them, current-or-recent estrogen therapy use was associated with an increased risk for the serous (51.4%, OR=1.63, 95% CI 1.27–2.09) and endometrioid (48.6%, OR=2.00, 95% CI 1.17–3.41). In addition, statistically significant trends in risk according to duration of use were seen among current-or-recent postmenopausal estrogen therapy users for both ovarian carcinoma histotypes (ptrend<0.001 for serous and endometrioid). Compared to controls, current-or-recent users for ten years or more had increased risks of serous ovarian carcinoma (36.8%, OR=1.73, 95% CI 1.26–2.38) and endometrioid ovarian carcinoma (34.9%, OR=4.03, 95% CI 1.91–8.49).

Conclusions

We found evidence of an increased risk of serous and endometriod histiotype ovarian carcinoma associated with postmenopausal estrogen therapy use, particularly of long duration. These findings emphasize that risk may be associated with extended estrogen therapy use.

Introduction

Menopausal hormone therapy (HT) containing estrogens is used to relieve climacteric symptoms and prevent osteoporosis among postmenopausal women. Prior to the results of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) in 2002,1 approximately 13 million women in the United States used HT, and while this number declined after the WHI, there are still approximately 5 million HT users.3

A comprehensive meta-analysis by Pearce et al, which included 13 population-based studies of women ages 18 to 79, showed that use of estrogen-alone therapy (ET) was associated with increased risk of ovarian carcinoma (relative risk per 5 years of use=1.22).4 Recent studies since then have shown similar results3,5–7, but important aspects remain unclear including whether differences exist by disease histotype or by duration and timing of use. The recent pooled analysis by the Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies on Ovarian Cancer (Collaborative Group)3 did report histotype-specific findings for serous and endometrioid cancers, but not for mucinous and clear cell cancers. They also found little trend in association with duration of use, contrary to the results of several studies.4,5,7–10 Notably, the Collaborative Group’s analysis included the majority of studies in Pearce et al’s meta-analysis in which a duration association was found. Clarifying these features could have important implications clinically and for risk stratification purposes.

ET is one of the most commonly used HT types, hence a more complete characterization of the ET-ovarian carcinoma association is warranted. We have undertaken a pooled analysis of data from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC) to assess ET’s histotype-specific, duration and recency of use associations with risk of ovarian carcinoma.

Materials and Methods

The OCAC is an international multidisciplinary consortium founded in 2005 (http://apps.ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/consortia/ocac/index.html). Since many groups worldwide are conducting studies to identify risk factors and genetic variation associated with ovarian carcinoma risk, the goal of the OCAC is to provide a forum where data from many individual studies with similar methods can be combined so reliable assessments of the risks associated with these factors can be determined. Data were sent by each study investigator to the consortium data coordinating center at Duke University, which cleaned and harmonized these data.

For the pooled analysis presented here, ten population-based case-control studies that were individually conducted and contributed data to the OCAC were included, with seven conducted in the United States and three in Europe. Details regarding each study have been published previously,11–21 but their main characteristics as well as any overlap with the Collaborative Group’s pooled analysis are presented in Table 1. Cases were women with initial diagnoses of primary ovarian carcinoma (women with primary fallopian tube and peritoneal tumors were excluded). Eligible tumor types included serous, mucinous, endometrioid, and clear cell ovarian carcinomas as well as other epithelial tumor types that were not classified as one of these four main ovarian carcinoma histotypes including mixed cell and Brenner tumors; borderline-malignant tumors were excluded. Controls were women with ovaries (a single ovary was acceptable), who had not been diagnosed with ovarian carcinoma at the time of interview. Reference dates for the women in the studies were usually the dates of diagnosis for the cases and the dates of interview for the controls. The data used in this analysis considered events occurring only prior to the reference dates. All studies included in this analysis had approval from ethics committees and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Table 1.

Description of studies included in analysis

| Study Name | Time Period | Location | Case Ascertainment | Control Ascertainment | Controls (mean/IQR for age) | Cases (mean/IQR for age) | Serous | Mucious | Endometrioid | Clear cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut Ovary Study (CON) 20 | 2002–2009 | USA; CT | Cancer registry or hospital records | Random digit dialing, Health Care Financing Administration records | 49 (60.9/13) | 54 (62.2/12) | 28 | 4 | 12 | 4 |

| Disease of the Ovary Study and their Evaluation (DOV) 19 | 2002–2009 | USA; WA | Cancer registry | Random digit dialing | 224 (66.8/12) | 159 (62.7/8) | 108 | 3 | 15 | 3 |

| German Ovarian Cancer Study (GER) 11, * | 1992–1998 | Germany | Admissions to all hospitals serving the study regions | Population registries | 89 (60.9/11) | 34 (61.5/12) | 17 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Hawaii Ovarian Cancer Study (HAW) 13 | 1994–2007 | USA; HI | Cancer registry | Department of Health Annual Survey, Health Care Financing Administration records | 40 (67.3/16) | 32 (66.1/17) | 18 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Hormones and Ovarian Cancer Prediction (HOP) 14, * | 2003–2008 | USA; western PA, northeast OH, western NY | Cancer registries, pathology databases, physicians’ offices | Random digit dialing | 201 (65.5/16) | 100 (66.6/15.6) | 57 | 5 | 17 | 4 |

| Malignant Ovarian Cancer Study (MAL) 21 | 1994–1999 | Denmark | Cancer registry, gynecological departments | Random digit dialing | 84 (62.6/13) | 47 (61.7/11) | 25 | 4 | 8 | 5 |

| North Carolina Ovarian Cancer Study (NCO) 15 | 1999–2008 | USA; NC | Cancer registry | Random digit dialing | 126 (62.7/11) | 153 (62.9/10) | 94 | 5 | 16 | 11 |

| New England Case-Control Study of Ovarian Cancer (NEC) 17 | 1999–2008 | USA; NH and eastern MA | Cancer registries, hospital tumor boards | Random digit dialing, town books, drivers’ license lists | 67 (63.2/11) | 50 (63.4/12) | 38 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| United Kingdom Ovarian Cancer Population Study (UKO) 12 | 2006–2007 | United Kingdom | Gynecological Oncology NHS centers | Women in the general population participating in the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) | 116 (64.0/9) | 56 (67.0/12) | 30 | 7 | 12 | 4 |

| University of Southern California. Study of Lifestyle and Women’s Health (USC) 16,18, * | 1993–2005 | USA; Los Angeles, CA | Cancer registry | Neighborhood controls | 224 (62.9/12.5) | 217 (64.7/12) | 152 | 17 | 20 | 7 |

| Total: | 1220 | 906† | 567† | 49† | 113† | 42† |

Note: All studies used in-person interviews except GER, which used self-completed questionnaires. MAL used either in-person or phone interviews.

Some of the study’s data were included in the Collaborative Group’s3 analysis.

Sum of numbers do not equal total number of cases because some cases were not classified as one of the four main histotypes considered.

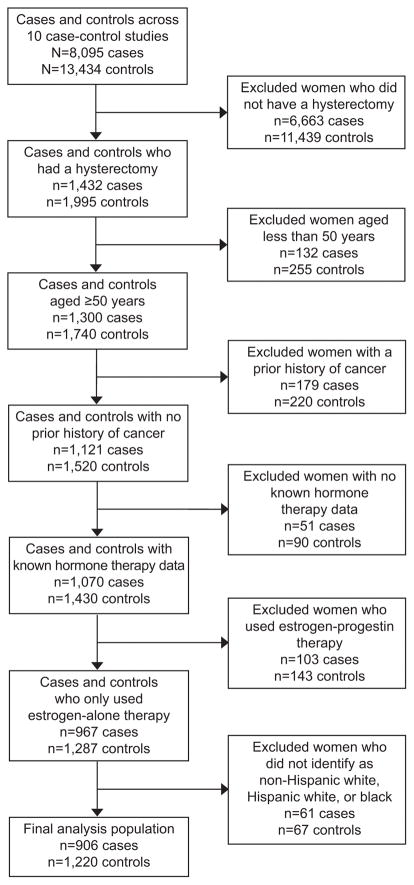

There was a total of 8,095 ovarian carcinoma patients and 13,434 controls across the ten OCAC studies. However, only women who reported having had a simple hysterectomy (without bilateral oophorectomy) were included in our analysis since ET use is very infrequent among women with intact uteri as it is a confirmed risk factor for endometrial cancer,22,23 leaving us with 1,432 cases and 1,995 controls. Additional exclusions included women who were less than 50 years of age at reference date (n=387), had a prior primary cancer diagnosis (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) (n=399), or were missing or had unknown HT information (n=141). We also excluded women who had used HT in an estrogen-progestin combined form (EPT) (n=246) for simplicity of presentation and since its use is likely to skew the primary effect of ET. Only women classified as non-Hispanic white, Hispanic white, or black were considered, hence our final subject set consisted of 2,126 women who had undergone hysterectomy, with 906 ovarian carcinoma cases and 1,220 controls (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of analysis exclusions

Information regarding HT use in all forms as well as potential confounding variables selected a priori, including age, race–ethnicity, education, oral contraceptive (OC) use, parity, endometriosis, tubal ligation, age at menarche, and body mass index (BMI) (typically one year before the reference date), was reported by means of self-completed questionnaires or in-person or phone interviews; we did not have information on previous salpingectomy or BRCA status at the time of this analysis. The questions used to ascertain HT use and, more specifically, ET use are presented in Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Age at menopause among women who have had a simple hysterectomy cannot be determined since the women are no longer menstruating but may still have functioning ovaries. Hence, in our primary analysis here, we have only considered ET use after age 50 given that 50 is the approximate average age at menopause for women in these populations.24 The majority of ET use before age 50 is thus likely to be use when the women were still having regular ovulatory cycles. Given that menopause plays a central role in ovarian carcinoma etiology, it is possible that the added estrogen exposure during the period when endogenous levels of estrogen are naturally high (i.e., before menopause) is less important than exposure at older ages, the majority of which will be in the postmenopausal period.25 Hence, for the analysis presented here, we have defined ET use as use after age 50, with women who only used ET before age 50 included in the baseline ‘never’ users group. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to see if the results were affected if true ‘never’ users were used as the baseline comparison group and if ET use was considered regardless of age at use.

A common approach to dealing with the problem of an unknown age at menopause for women who had a hysterectomy is to use their age at simple hysterectomy as their age at menopause. Hence, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the association between ET use and ovarian carcinoma risk using such an approach. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using ages 48 and 52 instead of 50 as the age at menopause.

ET use was categorized in terms of its recency and its duration of use (in years). Current use was defined as having last used ET within the past year, recent use as within the last one to four years, and past use as five or more years before the reference date. Because current and recent ET users showed similar effects, they were combined in the analyses presented here. Duration of ET use was summed over all episodes of use and the total categorized into the following groups: ‘never’ (including <1 year), 1 to <5 years, 5 to <10 years, and 10 or more years of use. Women who used ET for less than one year were included in the baseline ‘never’ users group as the recall of such short-term use may be greater in cases than controls. All data were cleaned and checked for internal consistency and clarifications were requested from the study investigators when needed.

Study, age, race–ethnicity, education, and OC use were included in all statistical models. We conditioned on study, age in five-year groups (50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75+; finer stratification after age 75 was not warranted due to small numbers), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic white, and black), and education (less than high school, high school, some college, and college graduate or higher) and we adjusted for OC use in categories as ordinal variables (‘never’ (including <1 year), 1 to <2 years, 2 to <5 years, 5 to <10 years, and 10 or more years for OC use). Tubal ligation, endometriosis, parity, BMI, and age at menarche were also considered, but their inclusion did not change the beta coefficients for the association between ET use and ovarian carcinoma (including overall, serous, or endometrioid) by more than 10% so the results given below are only adjusted for OC use. Overall, cases were missing 1.7% and 1.1% and controls 1.4% and 0.7% for OC use and education, respectively; missing categories were created for these women so their data could be used in the analysis.

Conditional logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between ET use and risk of ovarian carcinoma. This was done for all ovarian carcinoma cases combined and for its four main histotypes. Similar analytic approaches were applied when assessing the effects of recency and duration of use. All p-values reported are two-sided. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Data from 906 women with ovarian carcinoma (567 serous, 113 endometrioid, 49 mucinous, 42 clear cell, 135 epithelial but not specified as one of the four main histotypes) and 1,220 controls, all of whom had a simple hysterectomy, were included in our analysis. Of these women, 460 cases (50.8%) and 531 controls (43.5%) reported ever having used ET after age 50. Compared to the controls, women who had used ET after age 50 had a 30% increased risk of ovarian carcinoma as shown in Table 2 (50.8%, OR=1.30, 95% CI 1.06–1.59). Most of this risk elevation was observed among long-term users of ET for 10 years or more (both current-or-recent and past users).

Table 2.

Association between ET use over age 50 and risk of ovarian carcinoma overall

| Categories of ET Use | Number of controls | Number of cases | Median duration (years) | OR* | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never used | 689 | 446 | -- | 1.00 | -- | -- |

| Ever | 531 | 460 | 9.20 | 1.30 | 1.06 – 1.59 | 0.013 |

| 1 to<5 years | 149 | 92 | 2.70 | 1.00 | 0.72 – 1.39 | 0.99 |

| 5 to<10 years | 155 | 135 | 7.45 | 1.27 | 0.93 – 1.72 | 0.13 |

| 10+ years | 227 | 233 | 15.12 | 1.54 | 1.18 – 2.01 | 0.002 |

| p-trend: | 0.001 | |||||

| Current-or- recent users† | 432 | 392 | 10.00 | 1.35 | 1.09 – 1.67 | 0.006 |

| 1 to <5 years | 103 | 67 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 0.68 – 1.48 | 0.99 |

| 5 to <10 years | 120 | 112 | 7.20 | 1.35 | 0.96 – 1.90 | 0.087 |

| 10+ years | 209 | 213 | 15.20 | 1.53 | 1.17 – 2.02 | 0.002 |

| p-trend: | <0.001 | |||||

| Past users | 99 | 68 | 6.20 | 1.07 | 0.74 – 1.56 | 0.72 |

| 1 to <5 years | 46 | 25 | 2.20 | 1.01 | 0.59 – 1.74 | 0.97 |

| 5 to <10 years | 35 | 23 | 8.20 | 1.03 | 0.57 – 1.86 | 0.93 |

| 10+ years | 18 | 20 | 13.28 | 1.49 | 0.71 – 3.13 | 0.29 |

| p-trend: | 0.95 |

Note: OR=odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for oral contraceptive use (never (including <1), 1 to <2, 2 to <5, 5 to <10, 10+ years) and conditioned on age (50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75+), education (less than high school, high school, some college, college graduate or higher), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic white, black), and study.

Current-or-recent users included those who used ET within the last five years prior to their reference age.

In addition, the ET-ovarian carcinoma association appeared to show distinct histotype-specific associations as presented in Table 3 (serous and endometrioid) and Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx (mucinous and clear cell). Compared to the controls, current-or-recent ET use was statistically significantly associated with an increased risk of both serous (51.4%, OR=1.63, 95% CI 1.27–2.09) and endometrioid (48.6%, OR=2.00, 95% CI 1.17–3.41) histotypes, but not mucinous (31.3%, OR=0.93, 95% CI 0.43–2.00) and clear cell (39.0%, OR=0.87, 95% CI 0.40–1.88) histotypes, although the confidence limits for the mucinous and clear cell effect estimates were wide due to small numbers of cases. When we looked at high-grade (moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, undifferentiated) and low-grade (well differentiated) serous ovarian carcinomas separately, we found increased risks for both and hence the results for all serous cases combined are given.

Table 3.

Association between ET use after age 50 and risk of serous and endometrioid ovarian carcinoma

| SEROUS (N=567) | ENDOMETRIOID (N=113) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories of ET Use | Number of controls | Number of cases | OR* | 95% CI | p-value | Number of cases | OR* | 95% CI | p-value |

| Never used | 689 | 252 | 1.00 | -- | -- | 54 | 1.00 | -- | -- |

| Ever | 531 | 315 | 1.57 | 1.23 – 2.00 | <0.001 | 59 | 1.82 | 1.10 – 3.03 | 0.021 |

| 1 to <5 years | 149 | 62 | 1.26 | 0.86 – 1.83 | 0.24 | 10 | 0.98 | 0.45 – 2.15 | 0.97 |

| 5 to <10 years | 155 | 92 | 1.58 | 1.11 – 2.25 | 0.012 | 17 | 1.64 | 0.78 – 3.47 | 0.19 |

| 10+ years | 227 | 161 | 1.79 | 1.31 – 2.43 | <0.001 | 32 | 3.58 | 1.74 – 7.36 | <0.001 |

| p-trend: | <0.001 | p-trend: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Current-or-recent users† | 432 | 267 | 1.63 | 1.27 – 2.09 | <0.001 | 51 | 2.00 | 1.17 – 3.41 | 0.011 |

| 1 to <5 years | 103 | 46 | 1.37 | 0.88 – 2.14 | 0.16 | 7 | 0.88 | 0.35 – 2.19 | 0.78 |

| 5 to <10 years | 120 | 74 | 1.69 | 1.14 – 2.52 | 0.010 | 15 | 1.72 | 0.76 – 3.87 | 0.19 |

| 10+ years | 209 | 147 | 1.73 | 1.26 – 2.38 | <0.001 | 29 | 4.03 | 1.91 – 8.49 | <0.001 |

| p-trend: | <0.001 | p-trend: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Past users | 99 | 48 | 1.28 | 0.83 – 1.96 | 0.27 | 8 | 1.20 | 0.48 – 3.01 | 0.69 |

| 1 to <5 years | 46 | 16 | 1.05 | 0.55 – 2.01 | 0.89 | 3 | 1.35 | 0.37 – 4.94 | 0.66 |

| 5 to <10 years | 35 | 18 | 1.26 | 0.65 – 2.43 | 0.50 | 2 | 1.46 | 0.25 – 8.66 | 0.68 |

| 10+ years | 18 | 14 | 2.07 | 0.89 – 4.79 | 0.091 | 3 | 1.82 | 0.40 – 8.19 | 0.44 |

| p-trend: | 0.46 | p-trend: | 0.35 | ||||||

Note: OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval

Adjusted for oral contraceptive use (never (including <1), 1 to <2, 2 to <5, 5 to <10, 10+ years) and conditioned on age (50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75+), education (less than high school, high school, some college, college graduate or higher), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic white, black), and study.

Current-or-recent users included those who used ET within the last five years prior to their reference age.

Trends in association with duration of ET use were observed for the serous (ptrend<0.001) and endometrioid (ptrend<0.001) histotypes among current-or-recent ET users. Across all histotypes and duration and timing categories, ET appeared to have the strongest association with risk of endometrioid ovarian carcinoma; compared to the controls, current-or-recent, long-term users of ET for 10 years or more had over a four-fold increased risk (34.9%, OR=4.03, 95% CI 1.91–8.49). Current-or-recent, long-term users also had nearly a two-fold increased risk of serous ovarian carcinoma (36.8%, OR=1.73, 95% CI 1.26–2.38) when compared to controls. In addition, there appeared to be elevated risks of 1.49, 2.07, and 1.82 for overall, serous, and endometrioid ovarian carcinoma, respectively, when we compared past, long-term ET users to our baseline ‘never’ user group (Tables 2 and 3).

Because we assumed that all women in our analysis had an age at menopause of 50, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which each woman’s age at simple hysterectomy was used as her age at menopause, with the duration and timing of use variables re-categorized as such. The results by duration, timing of ET use, and histotype slightly attenuated with ORs of 1.46, 1.64, and 3.72 among current-or-recent ET users of 10 years or more for ovarian carcinoma overall and the serous and endometrioid histotypes, respectively (Appendix 3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). Sensitivity analyses that used a true ‘never’ user baseline group and redefined ET use regardless of age at menopause or with ages 48 and 52 as the age at menopause did not affect the overall findings (data not shown).

Discussion

Most population-based case-control studies and cohort studies have shown that ET use is associated with an increased risk of ovarian carcinoma and considering our findings together with those recently published by the Collaborative Group,3 it seems clear that ET is associated with risk for the serous and endometrioid histotypes of the disease. We found greater increased risk for those who used ET for 10 years or more, including those who last used it more than five years in the past, whereas the Collaborative Group3 did not. This was surprising given that the individual studies that contributed the most statistical information to their analysis (the Million Women Study (MWS)8 and the Danish Sex Hormone Register Study (DaHoRS)5) reported duration associations with ET use in their primary publications. The meta-analysis from Pearce and colleagues4 showed evidence of an ET duration-ovarian carcinoma risk association as well.

From a biological standpoint, an elevated risk of endometrioid ovarian carcinoma with ET use is not surprising given that the cells of origin are histologically similar to endometrial tissue, and ET use is a confirmed risk factor for endometrial cancer.22,26 Danforth et al had suggested that ET may act through similar biologic mechanisms in the development of endometrioid tumors as it does in endometrial cancer.27 Given the increased risk we see for endometrioid ovarian carcinoma and the well-established association between endometriosis and the endometrioid and clear cell histotypes,29 we assessed the ET risk association according to previous history of endometriosis or not, but did not see any heterogeneity in risk (data not shown).

Although the exact mechanism by which ET might affect serous and endometrioid ovarian carcinoma risk remains unknown, estrogens have long been implicated as etiologic factors.31 Ovarian carcinogenesis may be a result of the direct effects of unopposed estrogen and an estrogen-rich environment, which would potentially be enhanced by ET use. The use of ET may also directly stimulate the growth of premalignant or early malignant cells with long-term use increasing the risk of transformation or proliferation.32 In addition, the fallopian tube fimbriae, a proposed cell of origin for high-grade serous carcinoma, have been shown to proliferate at times when estrogenic influences are greater during the menstrual cycle,33,34 and this increased activity results in greater cell proliferation which may enhance the risk of mutations and malignant transformation. Estradiol has also been shown to increase ovarian carcinoma cell proliferation in vitro35 and influence the growth of ovarian tumors in a transplanted mouse model.36 Therefore, while several hypotheses have been put forth to explain ovarian carcinoma etiology, unopposed estrogen appears to play an important role.

Limitations of our analysis include the self-reported nature of our data. Because case-control studies inquire about previous exposures when subjects are already aware of their disease status, recall bias is possible as cases may be more likely to search for explanations for their disease and assign greater significance to past events than controls. However, studies have shown high agreement between self-reported estrogen use and prescription data.39 In addition, case patients have not been shown to preferentially report HT use more than controls.40 We considered ET use only after age 50 to be relevant in an attempt to mainly consider only use after ovarian function had ceased. Sensitivity analysis showed little effect when changing this to age 48 or 52, the latter which will only include use that is almost all in the postmenopausal period.

A potential concern with case-control studies such as those included in our analysis is that some ineligible women (those who had a bilateral oophorectomy) could have been recruited as controls even though they would not be at risk of developing ovarian carcinoma. However, oophorectomy results in a loss of estrogen production, which may make such women more likely to use ET, thus potentially biasing our findings towards the null. If this type of bias is present, any association between ET use and risk of ovarian carcinoma would be underestimated.

Our analysis offers evidence of an increased risk of ovarian carcinoma with ET use after the age of 50. This is especially true for risk of serous and endometrioid tumors for long durations of use, shedding light on the distinct histotype-specific etiologies. Although ET use has declined since the WHI, a significant number of women continue to use it today. Physicians and patients should be aware of the risk of ovarian carcinoma associated with its long-term use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by donations from by the family and friends of Kathryn Sladek Smith to the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund. It was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA14089, R01 CA61132, R01 CA141154, P01 CA17054, N01 PC67010, R03 CA113148, and R03 CA115195 [USC], R01 CA112523 and R01 CA87538 [DOV], R01 CA58598, N01 PC67001, and N01 CN55424 [HAW], R01 CA76016 [NCO], R01 CA54419 and P50 CA105009 [NEC], R01-CA074850 and R01-CA080742 [CON], R01-CA61107 [MAL], and R01 CA95023, R01 CA126841, M01 RR000056, P50 CA159981, and K07 CA80668 [HOP]); California Cancer Research Program (0001389V20170 and 2110200 [USC]); German Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany, Programme of Clinical Biomedical Research (01GB9401 [GER]); German Cancer Research Centre (GER); Danish Cancer Society (94 222 52 [MAL]; Mermaid I [MAL]; Eve Appeal (UKO); Oak Foundation (UKO); the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre (UKO); US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (W81XWH1010280 [NEC], DAMD17-02-1-0669 [HOP], and DAMD17-02-1-0666 [NCO]); Roswell Park Alliance Foundation (HOP); and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32 ES013678 for A.W.L.). Research reported in this publication was partially supported by NCI award number P30 CA008748 (PI: Thompson) to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. In addition, research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30 CA046592.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Usha Menon owns shares of Abcodia Ltd, a biomarker validation company. Dr. Marc Goodman is a consultant to Johnson and Johnson. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented at the American Association for Cancer Research 10th Biennial Ovarian Cancer Research Symposium Seattle University, Seattle, WA, September 8–9, 2014.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291(1):47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collaborative Group On Epidemiological Studies Of Ovarian C. Beral V, Gaitskell K, et al. Menopausal hormone use and ovarian cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of 52 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61687-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearce CL, Chung K, Pike MC, Wu AH. Increased ovarian cancer risk associated with menopausal estrogen therapy is reduced by adding a progestin. Cancer. 2009;115(3):531–539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morch LS, Lokkegaard E, Andreasen AH, Kruger-Kjaer S, Lidegaard O. Hormone therapy and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2009;302(3):298–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsilidis KK, Allen NE, Key TJ, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of ovarian cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(8):1075–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9782-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hildebrand JS, Gapstur SM, Feigelson HS, Teras LR, Thun MJ, Patel AV. Postmenopausal hormone use and incident ovarian cancer: Associations differ by regimen. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2928–2935. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beral V, Bull D, Green J, Reeves G Million Women Study C. Ovarian cancer and hormone replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2007;369(9574):1703–1710. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riman T, Dickman PW, Nilsson S, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer in Swedish women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(7):497–504. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moorman PG, Schildkraut JM, Calingaert B, Halabi S, Berchuck A. Menopausal hormones and risk of ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royar J, Becher H, Chang-Claude J. Low-dose oral contraceptives: protective effect on ovarian cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2001;95(6):370–374. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20011120)95:6<370::aid-ijc1065>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balogun N, Gentry-Maharaj A, Wozniak EL, et al. Recruitment of newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients proved challenging in a multicentre biobanking study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(5):525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lurie G, Terry KL, Wilkens LR, et al. Pooled analysis of the association of PTGS2 rs5275 polymorphism and NSAID use with invasive ovarian carcinoma risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(10):1731–1741. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9602-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness RB, Dodge RC, Edwards RP, Baker JA, Moysich KB. Contraception methods, beyond oral contraceptives and tubal ligation, and risk of ovarian cancer. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(3):188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moorman PG, Calingaert B, Palmieri RT, et al. Hormonal risk factors for ovarian cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(9):1059–1069. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu AH, Pearce CL, Tseng CC, Templeman C, Pike MC. Markers of inflammation and risk of ovarian cancer in Los Angeles County. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(6):1409–1415. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terry KL, De Vivo I, Titus-Ernstoff L, Shih MC, Cramer DW. Androgen receptor cytosine, adenine, guanine repeats, and haplotypes in relation to ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2005;65(13):5974–5981. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pike MC, Pearce CL, Peters R, Cozen W, Wan P, Wu AH. Hormonal factors and the risk of invasive ovarian cancer: a population-based case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(1):186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodelon C, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Doherty JA, Rossing MA. Sun exposure and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(12):1985–1994. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Risch HA, Bale AE, Beck PA, Zheng W. PGR +331 A/G and increased risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(9):1738–1741. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glud E, Kjaer SK, Thomsen BL, et al. Hormone therapy and the impact of estrogen intake on the risk of ovarian cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2253–2259. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beral V, Bull D, Reeves G Million Women Study C. Endometrial cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1543–1551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grady D, Gebretsadik T, Kerlikowske K, Ernster V, Petitti D. Hormone replacement therapy and endometrial cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(2):304–313. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00383-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morabia A, Costanza MC. International variability in ages at menarche, first livebirth, and menopause. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(12):1195–1205. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pike MC. Age-related factors in cancers of the breast, ovary, and endometrium. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(Suppl 2):59S–69S. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9681(87)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar VCR, Robbins SL. Basic Pathology. 6. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danforth KN, Tworoger SS, Hecht JL, Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of postmenopausal hormone use and ovarian cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(1):151–156. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, et al. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):385–394. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho SM. Estrogen, progesterone and epithelial ovarian cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:73. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou B, Sun Q, Cong R, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(3):641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donnez J, Casanas-Roux F, Caprasse J, Ferin J, Thomas K. Cyclic changes in ciliation, cell height, and mitotic activity in human tubal epithelium during reproductive life. Fertil Steril. 1985;43(4):554–559. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.George SH, Milea A, Shaw PA. Proliferation in the normal FTE is a hallmark of the follicular phase, not BRCA mutation status. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(22):6199–6207. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nash JD, Ozols RF, Smyth JF, Hamilton TC. Estrogen and anti-estrogen effects on the growth of human epithelial ovarian cancer in vitro. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(6):1009–1016. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198906000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laviolette LA, Hodgkinson KM, Minhas N, Perez-Iratxeta C, Vanderhyden BC. 17beta-estradiol upregulates GREB1 and accelerates ovarian tumor progression in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandini L, Pentti K, Tuppurainen M, Kroger H, Honkanen R. Agreement of self-reported estrogen use with prescription data: an analysis of women from the Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Prevention Study. Menopause. 2008;15(2):282–289. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181334b6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paganini-Hill A, Clark LJ. Comparison of patient recall of hormone therapy with physician records. Menopause. 2007;14(2):230–234. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000235364.50028.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.