Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) in humans and in animals leads to an acute and sustained increase in tissue glutamate concentrations within the brain, triggering glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity. Excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) are responsible for maintaining extracellular central nervous system glutamate concentrations below neurotoxic levels. Our results demonstrate that as early as 5 min and up to 2 h following brain trauma in brain-injured rats, the activity (Vmax) of EAAT2 in the cortex and the hippocampus was significantly decreased, compared with sham-injured animals. The affinity for glutamate (KM) and the expression of glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) and glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) were not altered by the injury. Administration of (R)-(−)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline (MS-153), a GLT-1 activator, beginning immediately after injury and continuing for 24 h, significantly decreased neurodegeneration, loss of microtubule-associated protein 2 and NeuN (+) immunoreactivities, and attenuated calpain activation in both the cortex and the hippocampus at 24 h after the injury; the reduction in neurodegeneration remained evident up to 14 days post-injury. In synaptosomal uptake assays, MS-153 up-regulated GLT-1 activity in the naïve rat brain but did not reverse the reduced activity of GLT-1 in traumatically-injured brains. This study demonstrates that administration of MS-153 in the acute post-traumatic period provides acute and long-term neuroprotection for TBI and suggests that the neuroprotective effects of MS-153 are related to mechanisms other than GLT-1 activation, such as the inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels.

Keywords: : EAAT2/GLT-1, glutamate uptake, MS-153, neuroprotection, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of injury-induced mortality and morbidity, with very few options to limit acute and long-term progression of secondary injury.1 Studies on TBI in humans and in animals have demonstrated an acute increase in tissue glutamate concentrations that remain high for up to 5 days in humans.2–7 The sustained elevation of extracellular glutamate levels leads to the overstimulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor subtype and the subsequent overloading of neurons with Ca2+ and Na+, resulting in the activation of phospholipases, endonucleases, and proteases such as calpain and eventual apoptotic and/or necrotic cell death.8 Clinical and experimental studies have determined that glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity is a significant contributor to acute post-traumatic neurodegenerative events.9–11

The termination of glutamate neurotransmission is achieved by rapid uptake of the released glutamate by presynaptic and/or astrocytic transporters12 in a process that is driven by and coupled to ion gradients.13–15 The glutamate transporter EAAT2 /GLT-1 (human/rat homolog)16 is expressed predominantly in glia throughout the brain and spinal cord, and accounts for approximately 95% of glutamate uptake in the central nervous system (CNS),17 implicating this isoform in the maintenance of extracellular glutamate homeostasis in normal and pathological conditions.18–20 Developing EAAT2 as a target for neuroprotection has been explored through the discovery of compounds that can either increase EAAT2 expression or increase the activity of the transporter.21,22 The β-lactam antibiotic ceftriaxone increases EAAT2 expression and has been shown to decrease neuronal damage in animal models of chronic neurodegenerative disorders,23–25 reduce brain glutamate levels, edema, and neuronal death after TBI in the rat,26–29 and attenuate neuropathic pain30, 31 and cytokine production after spinal cord injury in the rat.32 Compounds such as riluzole,33–37 guanosine,38,39 nicergoline,40 (R)-(−)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline (MS-153),41,42 and Parawixin1,43,44 have been reported to be neuroprotective in several models of CNS injury by increasing EAAT2 activity. In addition to reducing elevated brain glutamate levels induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion,45 MS-153 can inhibit voltage-gated calcium channels and prevent ischemia-induced release of glutamate from nerve terminals.46 MS-153 has been shown to affect other conditions that are believed to involve excessive glutamate signaling, such as the inhibition of morphine tolerance and dependence,47 the attenuation of behavioral sensitization development to phencyclidine,48,49 an anxiolytic effect in fear conditioning,50 and attenuation of the conditioned rewarding effects of morphine, methamphetamine, and cocaine.51 MS-153 was recently suggested to have potential as a therapeutic drug for the treatment of alcohol dependence.52,53

In the present study, the hypotheses that the glutamate transporter EAAT2/GLT-1 function is altered by TBI and that treatment with an EAAT2 activator after TBI will reduce neurodegeneration were tested. Lateral fluid-percussion brain injury of moderate severity decreased the Vmax of glutamate uptake in the cortex and hippocampus. Post-traumatic infusion of MS-153 for a period of 24 h decreased the extent of neurodegeneration, neuronal loss, microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) loss, and calpain activation. Importantly, the neuroprotective effect of MS-153 was sustained for up to 14 days after the injury. Interestingly, MS-153 could not reverse the injury-induced decrease in Vmax of glutamate uptake in synaptosomes ex vivo, suggesting that the neuroprotective effects of MS-153 in vivo may be unrelated to its ability to increase glutamate uptake.

Methods

All of the surgical, injury, and care protocols were approved by the Drexel University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are in agreement with the U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

TBI

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (325-411 g) were subjected to lateral fluid-percussion brain injury of 2.1-2.4 atm (n = 83) as previously described54; sham-injured animals (n = 24) were surgically prepared but did not receive the injury. Table 1 lists the animals used throughout the study.

Table 1.

Summary of Animals Used in the Study

| Study | n | Survival time | Injury status | Treatment status | Weight (g) | Apnea (sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate transporter activity and expression | 10 | 5 min- 2 h | Sham | NA | 372 ± 18 | NA |

| 7 | 5 min | Injured | NA | 381 ± 17 | 30 ± 7 | |

| 7 | 15 min | Injured | NA | 378 ± 13 | 36 ± 12 | |

| 7 | 30 min | Injured | NA | 389 ± 11 | 33 ± 13 | |

| 6 | 2 hours | Injured | NA | 387 ± 14 | 31 ± 9 | |

| Histology (Fluoro-Jade B, NeuN and MAP-2 loss) | 4 | 24 h | Sham | Saline | 346 ± 17 | NA |

| 2 | 24 h | Sham | MS-153 (low dose) | 363 ± 19 | NA | |

| 5 | 24 h | Injured | Saline | 379 ± 13 | 32 ± 16 | |

| 6 | 7 days | Injured | Saline | 388 ± 10 | 38 ± 26 | |

| 5 | 14 days | Injured | Saline | 363 ± 12 | 37 ± 6 | |

| 4 | 24 h | Injured | MS-153 (low dose) | 368 ± 21 | 26 ± 3 | |

| 7 | 7 days | Injured | MS-153 (low dose) | 391 ± 15 | 34 ± 13 | |

| 6 | 7 days | Injured | MS-153 (high dose) | 396 ± 12 | 28 ± 4 | |

| 5 | 14 days | Injured | MS-153 (high dose) | 380 ± 17 | 40 ± 5 | |

| Calpain activation | 4 | 24 h | Sham | Saline | 399 ± 30 | NA |

| 4 | 24 h | Sham | MS-153 (low dose) | 393 ± 22 | NA | |

| 7 | 24 h | Injured | Saline | 397 ± 22 | 30 ± 8 | |

| 8 | 24 h | Injured | MS-153 (low dose) | 401 ± 10 | 29 ± 6 |

Apnea was recorded from the time of impact to the time of regular breathing. Statistical analyses were performed as described in the Methods.

NA, not applicable; MS-153, (R)-(−)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline; MAP-2, microtubule-associated protein 2.

Drug administration

MS-153 was dissolved in saline and administered intravenously as a bolus dose at 5 min after the injury via the femoral vein and followed by the subcutaneous implantation of a mini osmotic pump (Model 2001D; Alze, Cupertino, CA) to deliver the drug for 24 h. Two doses of MS-153 were used; the low dose (25 mg/kg, followed by a continuous infusion of 12.5 mg/h for 23 h) and a high dose (50 mg/kg, followed by a continuous infusion of 25 mg/h for 23 h). The dose and dosing for MS-153 were based on studies in rat models of focal ischemia42,45 and pharmacokinetics that demonstrated that MS-153 crosses the blood–brain barrier and has a serum half-life of approximately 0.7 h.45 Animals that survived to 7 or 14 days following injury were re-anesthetized at 24 h after the injury using isoflurane to remove the osmotic pumps.

Glutamate uptake assays in synaptosomes

Brain- and sham-injured animals were euthanized by decapitation and tissue from the cortex and hippocampus below the impact site was dissected and immediately frozen at −20°C. When ready to perform uptake assays, frozen brain tissue was rapidly thawed and synaptosomes were prepared to examine kinetic parameters of glutamate uptake (Vmax and KM). These were calculated by fitting the raw data to a Michaelis-Menten equation44; Vmax and KM values were normalized to percentage of sham to control for variability among different assays.55 The kinetics of glutamate uptake in synaptosomes from brains of naïve rats in the presence of MS-153 were analyzed using a standard dose–response curve (0.1- 1000 μM of MS-153, pre-incubated for 40 min). The dose–response curves from at least three independent experiments were fitted to the Hill equation. To determine the effect of MS-153 on injury-induced alterations in kinetic parameters of glutamate uptake, synaptosomes from brain-injured rats were tested for glutamate uptake in the presence of 100μM MS-153

Immunoblot analysis

Analysis of GLT-1 and glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) expression after the injury was performed in synaptosomal preparations from brain- and sham-injured animals. Lysates from synaptosomes were subjected to SDS-PAGE (4 μg of protein per lane) and immunoblotted with antibodies against GLT-1 (1:10,000; Millipore, Billercia, CA) or GLAST (1:5,000; AbCam, Cambridge, MA); β-actin (1:1,000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was used as loading control. Detection was performed with infrared-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit DyLight 800, green and anti-mouse DyLight 680 red; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-COR Biosciences). Analysis of spectrin breakdown products (SBDP) were performed in tissue lysate from brains extracted 24 h after the injury as previously described.56

Histological analysis

Brain- and sham-injured animals were anesthetized, transcardially perfused with heparinized saline followed by 10% formalin, and brains processed for histologic evaluation as previously described. 57 Coronal sections (40 μm) were taken between approximately 1.5 mm and 6 mm posterior to bregma, reflecting the rostral-caudal extent of the injury. Staining and quantification of Fluoro-Jade B (FJ-B) reactivity (0.001%; Chemicon; Millipore), neuronal nucleus protein immunoreactivity (NeuN, 1:10,000, clone A60; Millipore), and loss of MAP-2 (1:5,000, clone AP-20; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were performed as previously described.58–60

Statistical analyses

Animal weights at the time of injury, duration of apnea immediately after injury, glutamate uptake kinetics, GLT-1/GLAST expression and SBDP generation in immunoblots, and FJ-B counts were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by appropriate post hoc analyses for comparisons between groups. NeuN cell counts were compared using a two-way ANOVA followed by a Neuman-Keuls post hoc test, using the right hemisphere values as control, as they were similar to both hemispheres in sham animals (not shown). Loss of MAP-2 immunoreactivity was compared using a Student's t-test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Three brain-injured rats (out of 83) died immediately post-injury (3.75 %). Surviving animals exhibited an apnea period of 22–60 sec with no statistical differences among groups (Table 1). Importantly, comparison of animal weights and apnea times across the groups of animals used for the various outcomes did not detect any differences (Table 1).

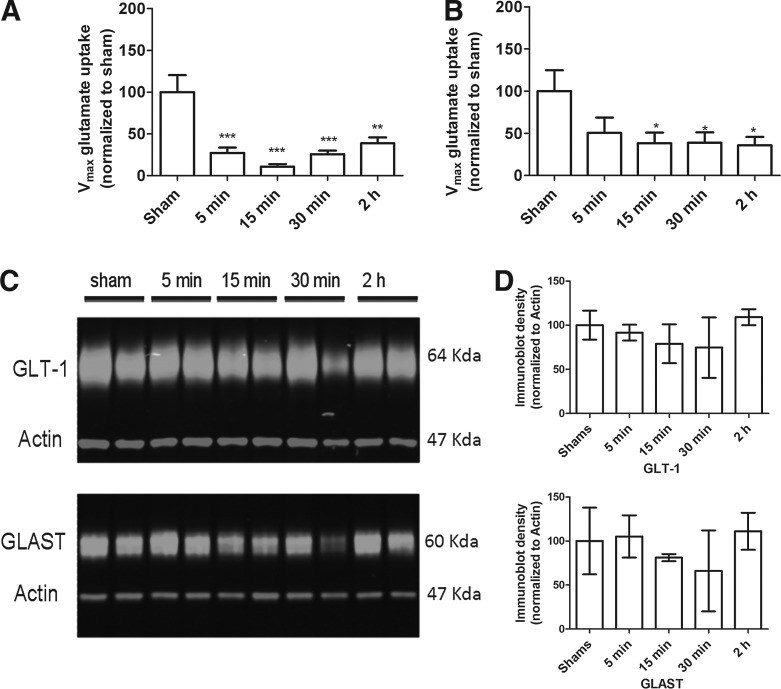

TBI decreased glutamate uptake activity

Lateral fluid-percussion brain injury of moderate severity resulted in a significant decrease of glutamate uptake (Vmax) in synaptosomes obtained from the site of maximal cortical injury (F[4,26] = 10.13; p < 0.001; Fig. 1A) and the hippocampus below the site of impact (F[4,30] = 2.8; p < 0.05; Fig. 1B); this decrease was observed as early as 5 min in the cortex and 15 min in the hippocampus, and was sustained up to 2 h post-injury, compared with sham-injured animals. The Vmax of glutamate uptake was not altered in the corresponding regions in the hemisphere contralateral to the impact site, compared with values for sham-injured rats (not shown). Additionally, the affinity for glutamate (KM) was unchanged in the brain-injured samples, compared with their sham-injured counterparts (not shown). The decrease in Vmax was not accompanied by changes in the expression of GLT-1 or GLAST in cortical (Fig. 1C, 1D) or in hippocampal synaptosomes (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of lateral fluid-percussion brain injury on glutamate uptake and GLT-1 expression. Vmax (nmol.mg−1.min−1) of 3H-L-glutamate uptake was measured in synaptosomes prepared from the injured cortex (A) and hippocampus (B) of brain-injured or sham-injured rats as described in the Methods. (C) Representative immunoblots illustrating GLT-1, glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) and actin expression from brain-injured or sham-injured rat synaptosomes. (D) Quantitative densitometric analysis of immunoblots. Bars represent means and standard deviation, *p < 0.05.

MS-153 decreased neurodegeneration after TBI

There was no FJ-B(+) reactivity visible in the cortex (Fig. 2A) and hippocampus (Fig. 2D) of sham-injured animals However, at 24 h following brain injury, FJ-B(+) cells were observed within the site of maximal injury in the cortex (Fig. 2B, 2C) and the pyramidal layer of area CA3 of the hippocampus (Fig. 2E, 2F) in both saline- (Fig. 2B, 2E) and MS-153–treated animals (Fig. 2C, 2F). Quantification of FJ-B (+) profiles at 1 day post-injury revealed that MS-153 administration decreased the number of FJ-B (+) cells in the cortex (F[2,10] = 37.2; p < 0.01) by ∼47% (Fig. 2G) and in the hippocampus (F[2,11] = 37.5; p < 0.01) by ∼33%, compared with saline-treated brain-injured animals (Fig. 2H). Interestingly, the reduction in FJ-B (+) cells remained evident at both 7 (Fig. 2I, 2J) and 14 days post-injury (Fig. 2K, 2L). Increasing the dose of MS-153 by 100% did not increase the extent of neuroprotection, with a reduction in neurodegeneration in the cortex of ∼47 and ∼49% (F[3, 19] = 14.8; p < 0.01; Fig. 2I, 2J) with low and high doses of MS-153, respectively, and ∼54% and ∼63% in the hippocampus (F[3,19] = 7.6; p < 0.05; Fig. 2I, 2J). After 14 days following injury and treatment with the high dose of MS-153, a reduction in neurodegeneration of ∼55% was observed in the cortex (F[2, 12] = 39.7; p < 0.0001; Fig. 2K) and of ∼39% in the hippocampus (F[2, 12] = 14.3; p < 0.05; Fig. 2L).

FIG. 2.

Effect of (R)-(−)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline (MS-153) on Fluoro-Jade B (FJ-B) reactivity in the cortex and hippocampus following lateral fluid-percussion brain injury. Representative photomicrographs of FJ-B–stained sections from the cortex (A-C) and area CA3 of the hippocampus (D-F) from sham-injured (A, D), vehicle-treated brain-injured (B, D) and MS-153-treated brain-injured rats (C, F). Note the absence of FJ-B (+) profiles in sham-injured animals (A, D). Scale bar in panel D represents 100 μm for all panels. Quantitative analyses are illustrated in graphs (G) and (H) 1 day post-injury, (I) and (J) 7 days post-injury, and (K) and (L) 14 days post-injury. The dose and dosing of MS-153 are described in the Methods. All values are presented as means and standard deviation. ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001, compared with sham values; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, compared with saline-treated values.

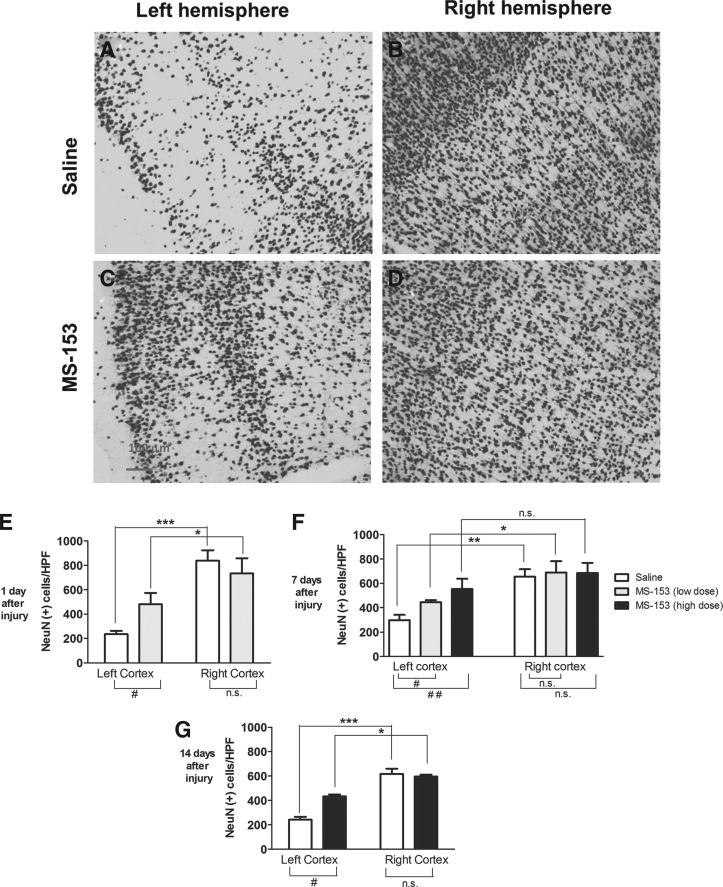

MS-153 increased neuronal survival

To determine whether reduction of FJ-B reactivity was associated with neuroprotection, the number of viable NeuN (+) neurons was counted in the cortex. A decrease in NeuN(+) cell number was observed in the cortex below the site of impact (Fig. 3A, 3C), compared with the hemisphere contralateral to the site of impact (Fig. 3B, 3D).

FIG. 3.

Effect of (R)-(−)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline (MS-153) on NeuN immunoreactivity following lateral fluid-percussion brain injury. Representative photomicrographs illustrating NeuN immunoreactivity in the cortex from the left (injured) hemisphere (A, C) and the right hemisphere (B, D) at 24 h after injury in vehicle-treated (A, B) and MS-153-treated (C, D) brain-injured rats. Scale bar in panel C represents 100 μm for all panels. Analyses of NeuN (+) counts in the cortex at 1 (E), 7 (F) and 14 days (G) after injury. Bars represent mean and standard deviation. #p < 0.01; ##p < 0.001.

At 1 day post-injury, an increase of ∼104% in the number of NeuN (+) cells was observed in MS-153–treated, brain-injured animals, compared with their vehicle-treated counterparts (Fig. 3E). A two-way ANOVA revealed an injury effect (hemisphere, F[1,12] = 52.2; p < 0.001), a treatment effect (F[1,12] = 1.4; p < 0.05) and an interaction effect (F[1,12] = 8.7; p < 0.05; Fig. 3E). Post hoc analysis indicated a treatment effect on the left hemisphere (p < 0.05) but not on the right hemisphere (p > 0.05). At 7 days, significant hemisphere (F[1,34] = 31.5; p < 0.001) and treatment effects (F[2,34] = 4.5; p < 0.05) were observed in the absence of an interaction between treatment and hemisphere (F[2,34] = 0.5; p > 0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed a dose–dependent effect of MS-153 on NeuN (+) quantification in the left hemisphere: the low dose increased the number of NeuN (+) neurons by ∼49% (p < 0.05) and the high dose by ∼85% (p < 0.01), compared with vehicle-treated animals. No treatment effect was observed in the right hemisphere (p > 0.05; Fig. 3F). At 14 days after the injury, a two-way ANOVA revealed a significant hemisphere effect (F[1,18] =53.1; p < 0.001), a treatment effect (F[1,18] = 53.6; p < 0.001) and an interaction effect (F [1,18] = 82.1; p < 0.001; Fig. 3G). Post hoc analysis indicated a treatment effect on the left hemisphere (p < 0.05) but not on the right hemisphere (p > 0.05).

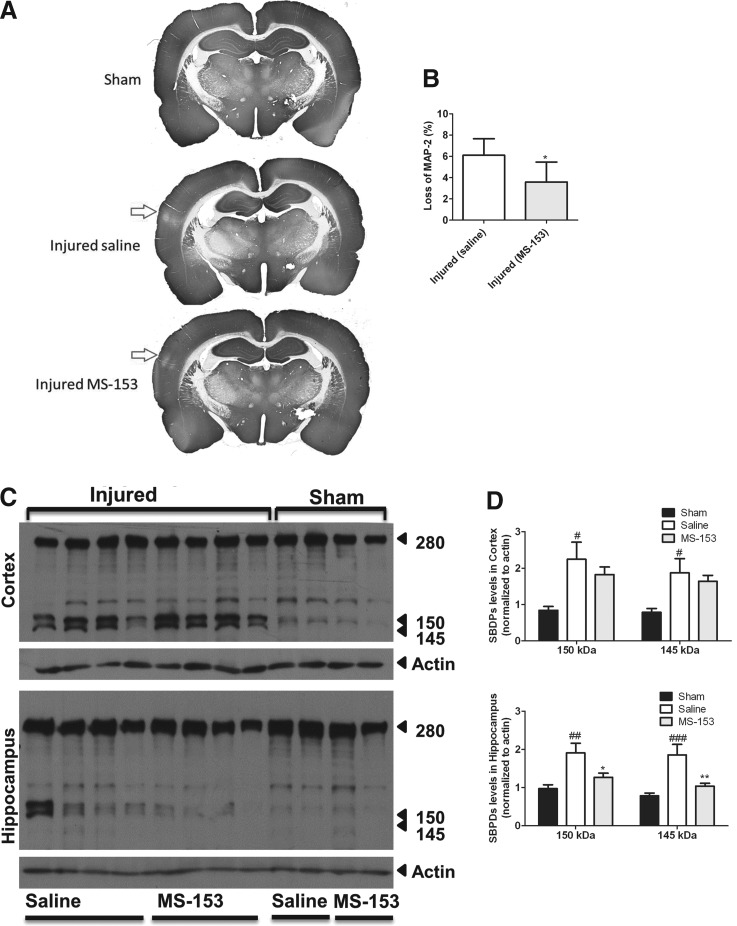

MS-153 decreased MAP-2 loss after TBI

Previous studies have reported that MAP-2 immunoreactivity was profoundly diminished in the cortex and hippocampus in brain-injured animals by 10 min and remains diminished up to 7 days after injury.61 MAP-2 loss is linked to the apoptotic process and is a powerful indicator of the extent of damage caused by brain injury.62,63 Figure 4A illustrates representative coronal sections from sham- (upper image) and brain-injured rats (middle and bottom images), with loss of MAP-2 reactivity depicted by the arrow in brain-injured animals treated either with saline (middle image) or MS-153 (bottom image), representing the area of maximal cortical injury. Quantification revealed that MS-153 significantly decreased the loss of MAP-2 staining, compared with saline-treatment by ∼41.2% (t[8] = 2.3; p < 0.05; Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effect of (R)-(−)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline (MS-153) on microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) immunoreactivity and calpain activation following lateral fluid-percussion brain injury. (A) Representative photomicrographs illustrating showing MAP-2 immunoreactivity in sham-injured rats (upper panel) and in saline-treated, brain-injured rats after traumatic brain injury (middle panel) and MS-153-treated, brain-injured rats (lower panel). Arrow represents the site of maximal cortical injury as denoted by a loss of MAP-2 immunoreactivity. (B) Quantitative analysis of MAP-2 loss. *p < 0.05. (C) Representative immunoblots depicting spectrin breakdown products (SBDPs) in lysates of cortex (upper panel) and hippocampus (lower panel) from sham- and brain-injured animals. Note the presence of the 150-145 kDa doublet in brain-injured samples. (D) Quantification of SBDPs in cortex (upper panel) and hippocampus (lower panel). #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01, compared with sham values; *p < 0.05, compared with saline-treated values.

MS-153 decreased calpain-mediated spectrin proteolysis in the hippocampus

Calpain activation has been implicated in the acute neurodegenerative events following lateral fluid-percussion brain trauma.56 Figure 4C displays spectrin proteolysis in brain-injured tissue at 24 h after injury. Injured samples from the cortex and hippocampus exhibit the typical calpain-mediated spectrin breakdown products at 150 and 145kDa, which were minimally present in sham-injured samples. The relative optical density of both 150 and 145 kDa bands in the injured animals (white bars) was increased, compared with sham-injured animals (black bars, Fig. 4D). In the cortex, the 150kDa band was increased by ∼166% (F[2,21] = 5.7; p < 0.05) and the 145kDa band by ∼138 % (F[2,21] = 5.1; p < 0.05), compared with shams. Even though MS-153 treatment does not significantly reduce SBDPs in cortex (compared with saline), SBDP expression in the MS-153-treated injured cortex was no longer significantly different from sham-injured animals. In the hippocampus, the 150 kDa band was increased by ∼95 % (F[2,21] = 7.9; p < 0.01) and the 145kDa band by 136% (F[2,21] = 10.8; p < 0.001), compared with sham-injured values. Quantification revealed that MS-153 treatment (gray bars) attenuated spectrin breakdown in hippocampus of both 150kDa (F(2,21) = 7.9; p < 0.05), and 145kDa (F[2,21] = 10.8; p < 0.01) bands.

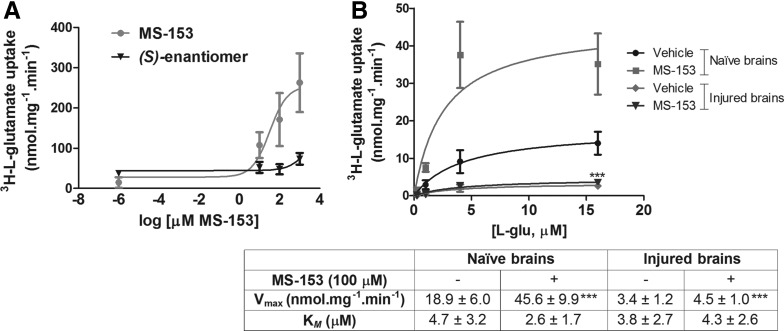

MS-153 increased glutamate transporter activity only in naïve brain preparations

The (R)-enantiomer of MS-153, but not the(S)-enantiomer, increased glutamate uptake in synaptosomes prepared from naïve rat brains in a dose–dependent manner, with an ED50 value of 32.3 ± 0.4 μM (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B illustrates glutamate uptake saturation curves displaying classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics with MS-153 increasing the Vmax of glutamate uptake by ∼140%, compared with phosphate-buffered saline-treated synaptosomes from naïve brains, with no effect on the affinity for the substrate glutamate (KM). The Vmax of glutamate transport in synaptosomes obtained from the cortex at 2 h after injury was decreased by 82% in the presence of phosphate-buffered saline, and 76% in the presence of MS-153 (100 μM, table in Fig. 5B). A two-way ANOVA revealed an injury effect (F[1,19] = 56.7; p < 0.001), a treatment effect (F[1,19] = 233.7; p < 0.001) and an interaction effect (F[1,19] = 47.7; p < 0.001; Fig. 5B). Post hoc analyses revealed that MS-153 significantly increased Vmax in naïve brain synaptosomes (p < 0.001), but not in synaptosomes from injured brains. Naïve values of glutamate transport were not different from sham values (not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effect of (R)-(−)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline (MS-153) on glutamate uptake in synaptosomes ex vivo. (A) Glutamate uptake in synaptosomes from naïve rat brains following incubation with increasing concentrations of the active (R)- or inactive (S)-enantiomer of MS-153. (B) Graph illustrates kinetic analysis of L-glutamate uptake in synaptosomes from either naïve rat brains or injured-brains pre-incubated with 100 μM MS-153. Values for Vmax and KM are presented in the table; KM was not statistically different between the groups. ***p < 0.001 drug, compared with phosphate-buffered saline buffer; ###p < 0.001 injured, compared with naïve values.

Discussion

Lateral fluid-percussion brain injury of moderate severity resulted in a decrease in glutamate uptake activity in synaptosomes from the injured cortex and hippocampus, with no alterations in either the affinity for glutamate or the expression of GLT-1 or GLAST. This supports the idea that the elevated extracellular concentration of glutamate that has been reported following brain injury is partially a result of diminished glutamate uptake and clearance.9

In the present study, we did not observe changes in the total levels of GLT-1 and GLAST up to 2 h post-injury. In the hours/days following brain trauma in the rat64 or in human,65,66 GLT-1 expression has been reported to decrease in the cortex and hippocampus. Further, antisense knockdown of GLT-1 exacerbates neuronal damage following contusive brain trauma in the rat.67 The decrease in Vmax of glutamate uptake activity in the absence of down-regulation of total levels of GLT-1 that was observed in our study suggests that the transporter may be internalized. One mechanism of rapid (within minutes) intracellular trafficking of sodium-dependent neurotransmitter transporters like GLT-1 is linked to the activation of protein kinase C (PKC),68 which is activated post-TBI.69 The internalization model for the decrease in activity also may explain the inability of MS-153, when incubated with synaptosomes ex vivo, to restore Vmax of glutamate uptake in brain-injured samples. Future studies will confirm whether GLT-1/EAAT2 is internalized as a result of the injury using cross-linking assays.70

Another possible explanation for the decrease in Vmax by the injury is reversal of glutamate transport. Under physiological conditions, the conventional transport direction is inward and dependent on the Na+ and K+ gradients; however, in conditions when extracellular Na+ and intracellular K+ decrease, glutamate can be transported in the outward direction.71–73 Indeed, it has been reported that reversal of glutamate transport via GLT-1 is an important event in glutamate release following ischemia.74,75 It is well established that ion gradients that drive glutamate uptake and the enzymes, such as the Na+-K+-ATPase, that maintain these ion gradients, are compromised in the traumatically-injured brain.76,77 Importantly, massive increases in extracellular potassium and the indiscriminate release of glutamate has been reported following concussive brain injury.78 Nonetheless, because we assessed accumulation of radiolabeled glutamate into synaptosomes ex vivo, it is not possible to determine if the lower Vmax is a result of reversal of transport.

The lack of an effect of MS-153 on synaptosomal glutamate uptake in samples from injured brains suggests that the neuroprotective effects of MS-153 seen in our study may be attributed to cellular mechanisms other than a direct effect on GLT-1 activity. MS-153 can block voltage-gated calcium channels through a mechanism that is protein kinase C (PKC)–dependent46; MS-153 inhibits the translocation and activation of PKC-γ that leads to the suppression of the calcium channel current.45 Calcium channel blockers such as emopamil79 and nimodipine80 have been shown to be neuroprotective in TBI. Further, the decrease in calpain-mediated spectrin proteolysis would suggest that the effects of MS-153 are mediated via a reduction of calcium influx into injured cells.46 Several classes of compounds including NMDA receptor antagonists81 and compounds that target calcium influx,79,82 have been shown to ameliorate cellular damage and neurologic deficits, as well as cognitive decline and motor impairments caused by TBI. In models of brain injury, glutamate receptor antagonists, such as kynurenate,83 NBQX, and CGS 19755,84 have been reported to partially ameliorate cytoskeletal injury with preserved immuno-labeling of MAP-2 and to reduce the accumulation of calpain-cleaved spectrin byproducts. However, these compounds have been associated with substantial adverse effects, making them less attractive for translation to patients.85,86 As a result, there currently are no approved pharmacological treatments available for directly halting the deleterious effects of glutamate excitotoxicity.87,88

In conclusion, moderate TBI induced by lateral fluid-percussion trauma resulted in a decreased rate of glutamate uptake in the injured hemisphere, and the GLT-1 activator MS-153 reduced neurodegeneration and neuronal loss for up to 14 days. Whereas MS-153 increased the rate of glutamate uptake in synaptosomes from naïve rat brain, it did not restore the injury-induced decreased activity of GLT-1. However, the lack of involvement of GLT-1 in the neuroprotective effects of MS-153 is based on the ex vivo synaptosomal assays and cannot completely rule out the contribution of glutamate transport activation in vivo to the neuroprotective effect of MS-153. Currently, there is a lack of approved pharmacological treatments for directly reducing the effects of excitotoxicity after acute brain trauma. Also, it is worth noting that MS-153 attenuates excitotoxic effects without blocking glutamate receptors, a process known to cause severe adverse effects.19 To elucidate the role of enhanced GLT-1 activity in modifying pathological outcomes following TBI and to pursue its promise as a therapeutic target in TBI, better tools and more selective GLT-1 compounds would be required.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Rupal Prasad for performing the spectrin immunoblotting experiments. The authors also acknowledge Dr. Joseph M. Salvino for synthesis of the compound MS-153 through Astatech Inc. (Bristol, PA) and for helpful discussions, and Craig Thomas (National Institutes of Health [NIH], National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences), for the chiral separation of the compound.

The study was supported by DUCOM Tobacco Settlement grant 001564-002 to A.C.K.F. and NIH 5R01NS065017-03 to R.R.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Janowitz T. and Menon D.K. (2010). Exploring new routes for neuroprotective drug development in traumatic brain injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer A.M., Marion D.W., Botscheller M.L., Swedlow P.E., Styren S.D., and DeKosky S.T. (1993). Traumatic brain injury-induced excitotoxicity assessed in a controlled cortical impact model. J. Neurochem. 61, 2015–2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown J.I., Baker A.J., Konasiewicz S.J., and Moulton R.J. (1998). Clinical significance of CSF glutamate concentrations following severe traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurotrauma 15, 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vespa P., Prins M., Ronne-Engstrom E., Caron M., Shalmon E., Hovda D.A., Martin N.A., and Becker D.P. (1998). Increase in extracellular glutamate caused by reduced cerebral perfusion pressure and seizures after human traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study. J. Neurosurg. 89, 971–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker A.J., Moulton R.J., MacMillan V.H., and Shedden P.M. (1993). Excitatory amino acids in cerebrospinal fluid following traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurosurg. 79, 369–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson P., Hillered L., Ponten U., and Ungerstedt U. (1990). Changes in cortical extracellular levels of energy-related metabolites and amino acids following concussive brain injury in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10, 631–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto T., Rossi S., Stiefel M., Doppenberg E., Zauner A., Bullock R., and Marmarou A. (1999). CSF and ECF glutamate concentrations in head injured patients. Acta Neurochir. Supplement 75, 17–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghupathi R. (2004). Cell death mechanisms following traumatic brain injury. Brain Pathol. 14, 215–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faden A.I., Demediuk P., Panter S.S., and Vink R. (1989). The role of excitatory amino acids and NMDA receptors in traumatic brain injury. Science 244, 798–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi J.H. and Hazell A.S. (2006). Excitotoxic mechanisms and the role of astrocytic glutamate transporters in traumatic brain injury. Neurochem. Int. 48, 394–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothman S.M. and Olney J.W. (1995). Excitotoxicity and the NMDA receptor–still lethal after eight years. Trends Neurosci. 18, 57–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danbolt N.C. (2001). Glutamate uptake. Prog. Neurobiol. 65, 1–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szatkowski M. and Attwell D. (1994). Triggering and execution of neuronal death in brain ischaemia: two phases of glutamate release by different mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 17, 359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amara S.G. and Fontana A.C. (2002). Excitatory amino acid transporters: keeping up with glutamate. Neurochem. Int. 41, 313–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gegelashvili G., Dehnes Y., Danbolt N.C., and Schousboe A. (2000). The high-affinity glutamate transporters GLT1, GLAST, and EAAT4 are regulated via different signalling mechanisms. Neurochem. Int. 37, 163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pines G., Danbolt N.C., Bjoras M., Zhang Y., Bendahan A., Eide L., Koepsell H., Storm-Mathisen J., Seeberg E., and Kanner B.I. (1992). Cloning and expression of a rat brain L-glutamate transporter. Nature 360, 464–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suchak S.K., Baloyianni N.V., Perkinton M.S., Williams R.J., Meldrum B.S., and Rattray M. (2003). The ‘glial’ glutamate transporter, EAAT2 (Glt-1) accounts for high affinity glutamate uptake into adult rodent nerve endings. J. Neurochem. 84, 522–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maragakis N.J., Dykes-Hoberg M., and Rothstein J.D. (2004). Altered expression of the glutamate transporter EAAT2b in neurological disease. Ann. Neurol. 55, 469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheldon A.L. and Robinson M.B. (2007). The role of glutamate transporters in neurodegenerative diseases and potential opportunities for intervention. Neurochem. Int. 51, 333–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauriat T.L. and McInnes L.A. (2007). EAAT2 regulation and splicing: relevance to psychiatric and neurological disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 12, 1065–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim K., Lee S.G., Kegelman T.P., Su Z.Z., Das S.K., Dash R., Dasgupta S., Barral P.M., Hedvat M., Diaz P., Reed J.C., Stebbins J.L., Pellecchia M., Sarkar D., and Fisher P.B. (2011). Role of excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EAAT2) and glutamate in neurodegeneration: opportunities for developing novel therapeutics. J. Cell. Physiol. 226, 2484–2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunlop J. (2006). Glutamate-based therapeutic approaches: targeting the glutamate transport system. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 6, 103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothstein J.D., Patel S., Regan M.R., Haenggeli C., Huang Y.H., Bergles D.E., Jin L., Dykes Hoberg M., Vidensky S., Chung D.S., Toan S.V., Bruijn L.I., Su Z.Z., Gupta P., and Fisher P.B. (2005). Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature 433, 73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry J.D., Shefner J.M., Conwit R., Schoenfeld D., Keroack M., Felsenstein D., Krivickas L., David W.S., Vriesendorp F., Pestronk A., Caress J.B., Katz J., Simpson E., Rosenfeld J., Pascuzzi R., Glass J., Rezania K., Rothstein J.D., Greenblatt D.J., and Cudkowicz M.E. (2013). Design and initial results of a multi-phase randomized trial of ceftriaxone in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PloS One 8, e61177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen B.A., Baron D.A., Kim J.K., Unterwald E.M., and Rawls S.M. (2011). β-Lactam antibiotic produces a sustained reduction in extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Amino Acids 40, 761–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan X.D., Wei J., and Xiao G.M. (2011). [Effects of beta-lactam antibiotics ceftriaxone on expression of glutamate in hippocampus after traumatic brain injury in rats]. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 40, 522–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodrich G.S., Kabakov A.Y., Hameed M.Q., Dhamne S.C., Rosenberg P.A., and Rotenberg A. (2013). Ceftriaxone treatment after traumatic brain injury restores expression of the glutamate transporter, GLT-1, reduces regional gliosis, and reduces post-traumatic seizures in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 30, 1434–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui C., Cui Y., Gao J., Sun L., Wang Y., Wang K., Li R., Tian Y., Song S., and Cui J. (2013). Neuroprotective effect of ceftriaxone in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Neurol. Sci. 35, 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei J., Pan X., Pei Z., Wang W., Qiu W., Shi Z., and Xiao G. (2012). The beta-lactam antibiotic, ceftriaxone, provides neuroprotective potential via anti-excitotoxicity and anti-inflammation response in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg 73, 654–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos K.M., Lewis M.T., Morgan K.N., Crysdale N.Y., Kroll J.L., Taylor F.R., Harrison J.A., Sloane E.M., Maier S.F., and Watkins L.R. (2010). Spinal upregulation of glutamate transporter GLT-1 by ceftriaxone: therapeutic efficacy in a range of experimental nervous system disorders. Neuroscience 169, 1888–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholson K.J., Gilliland T.M., and Winkelstein B.A. (2014). Upregulation of GLT-1 by treatment with ceftriaxone alleviates radicular pain by reducing spinal astrocyte activation and neuronal hyperexcitability. J. Neurosci. Res. 92, 116–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amin B., Hajhashemi V., Hosseinzadeh H., and Abnous K. (2012). Antinociceptive evaluation of ceftriaxone and minocycline alone and in combination in a neuropathic pain model in rat. Neuroscience 224, 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azbill R.D., Mu X., and Springer J.E. (2000). Riluzole increases high-affinity glutamate uptake in rat spinal cord synaptosomes. Brain Res. 871, 175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mu X., Azbill R.D., and Springer J.E. (2000). Riluzole and methylprednisolone combined treatment improves functional recovery in traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 17, 773–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang C., Raghupathi R., Saatman K.E., Smith D.H., Stutzmann J.M., Wahl F., and McIntosh T.K. (1998). Riluzole attenuates cortical lesion size, but not hippocampal neuronal loss, following traumatic brain injury in the rat. J. Neurosci. Res. 52, 342–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntosh T.K., Smith D.H., Voddi M., Perri B.R., and Stutzmann J.M. (1996). Riluzole, a novel neuroprotective agent, attenuates both neurologic motor and cognitive dysfunction following experimental brain injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 13, 767–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brothers H.M., Bardou I., Hopp S.C., Kaercher R.M., Corona A.W., Fenn A.M., Godbout J.P., and Wenk G.L. (2013). Riluzole partially rescues age-associated, but not LPS-induced, loss of glutamate transporters and spatial memory. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 8, 1098–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frizzo M.E., Schwalm F.D., Frizzo J.K., Soares F.A., and Souza D.O. (2005). Guanosine enhances glutamate transport capacity in brain cortical slices. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 25, 913–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frizzo M.E., Lara D.R., Dahm K.C., Prokopiuk A.S., Swanson R.A., and Souza D.O. (2001). Activation of glutamate uptake by guanosine in primary astrocyte cultures. Neuroreport 12, 879–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishida A., Iwata H., Kudo Y., Kobayashi T., Matsuoka Y., Kanai Y., and Endou H. (2004). Nicergoline enhances glutamate uptake via glutamate transporters in rat cortical synaptosomes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 27, 817–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimada F., Shiga Y., Morikawa M., Kawazura H., Morikawa O., Matsuoka T., Nishizaki T., and Saito N. (1999). The neuroprotective agent MS-153 stimulates glutamate uptake. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 386, 263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawazura H., Takahashi Y., Shiga Y., Shimada F., Ohto N., and Tamura A. (1997). Cerebroprotective effects of a novel pyrazoline derivative, MS-153, on focal ischemia in rats. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 73, 317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fontana A.C., de Oliveira Beleboni R., Wojewodzic M.W., Ferreira Dos Santos W., Coutinho-Netto J., Grutle N.J., Watts S.D., Danbolt N.C., and Amara S.G. (2007). Enhancing glutamate transport: mechanism of action of Parawixin1, a neuroprotective compound from Parawixia bistriata spider venom. Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 1228–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fontana A.C., Guizzo R., de Oliveira Beleboni R., Meirelles E.S.A.R., Coimbra N.C., Amara S.G., dos Santos W.F., and Coutinho-Netto J. (2003). Purification of a neuroprotective component of Parawixia bistriata spider venom that enhances glutamate uptake. Br. J. Pharmacol. 139, 1297–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Umemura K., Gemba T., Mizuno A., and Nakashima M. (1996). Inhibitory effect of MS-153 on elevated brain glutamate level induced by rat middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke 27, 1624–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uenishi H., Huang C.S., Song J.H., Marszalec W., and Narahashi T. (1999). Ion channel modulation as the basis for neuroprotective action of MS-153. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 890, 385–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakagawa T., Ozawa T., Shige K., Yamamoto R., Minami M., and Satoh M. (2001). Inhibition of morphine tolerance and dependence by MS-153, a glutamate transporter activator. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 419, 39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abekawa T., Honda M., Ito K., Inoue T., and Koyama T. (2002). Effect of MS-153 on the development of behavioral sensitization to stereotypy-inducing effect of phencyclidine. Brain Res. 926, 176–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abekawa T., Honda M., Ito K., Inoue T., and Koyama T. (2002). Effect of MS-153 on the development of behavioral sensitization to locomotion- and ataxia-inducing effects of phencyclidine. Psychopharmacology 160, 122–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X., Inouei T., Abekawai T., YiRui F., and Koyama T. (2004). Effect of MS-153 on the acquisition and expression of conditioned fear in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 505, 145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakagawa T., Fujio M., Ozawa T., Minami M., and Satoh M. (2005). Effect of MS-153, a glutamate transporter activator, on the conditioned rewarding effects of morphine, methamphetamine and cocaine in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 156, 233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alhaddad H., Kim N.T., Aal-Aaboda M., Althobaiti Y.S., Leighton J., Boddu S.H., Wei Y., and Sari Y. (2014). Effects of MS-153 on chronic ethanol consumption and GLT1 modulation of glutamate levels in male alcohol-preferring rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aal-Aaboda M., Alhaddad H., Osowik F., Nauli S.M., and Sari Y. (2015). Effects of (R)-(-)-5-methyl-1-nicotinoyl-2-pyrazoline on glutamate transporter 1 and cysteine/glutamate exchanger as well as ethanol drinking behavior in male, alcohol-preferring rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 93, 930–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McIntosh T.K., Vink R., Noble L., Yamakami I., Fernyak S., Soares H., and Faden A.L. (1989). Traumatic brain injury in the rat: characterization of a lateral fluid-percussion model. Neuroscience 28, 233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y., Sattler R., Yang E.J., Nunes A., Ayukawa Y., Akhtar S., Ji G., Zhang P.W., and Rothstein J.D. (2011). Harmine, a natural beta-carboline alkaloid, upregulates astroglial glutamate transporter expression. Neuropharmacology 60, 1168–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saatman K.E., Bozyczko-Coyne D., Marcy V., Siman R., and McIntosh T.K. (1996). Prolonged calpain-mediated spectrin breakdown occurs regionally following experimental brain injury in the rat. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 55, 850–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Creed J.A., DiLeonardi A.M., Fox D.P., Tessler A.R., and Raghupathi R. (2011). Concussive brain trauma in the mouse results in acute cognitive deficits and sustained impairment of axonal function. J. Neurotrauma 28, 547–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huh J.W., Widing A.G., and Raghupathi R. (2008). Midline brain injury in the immature rat induces sustained cognitive deficits, bihemispheric axonal injury and neurodegeneration. Exp. Neurol. 213, 84–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sato M., Chang E., Igarashi T., and Noble L.J. (2001). Neuronal injury and loss after traumatic brain injury: time course and regional variability. Brain Res. 917, 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saatman K.E., Feeko K.J., Pape R.L., and Raghupathi R. (2006). Differential behavioral and histopathological responses to graded cortical impact injury in mice. J. Neurotrauma 23, 1241–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saatman K.E., Graham D.I., and McIntosh T.K. (1998). The neuronal cytoskeleton is at risk after mild and moderate brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 15, 1047–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Castillo M.R. and Babson J.R. (1998). Ca(2+)-dependent mechanisms of cell injury in cultured cortical neurons. Neuroscience 86, 1133–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu S.Y., Chen Y.T., Tseng M.Y., Hung C.C., Chiang W.F., Chen H.R., Shieh T.Y., Chen C.H., Jou Y.S., and Chen J.Y. (2008). Involvement of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) in oral cancer cell motility: a novel biological function of MAP2 in non-neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 366, 520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rao V.L., Baskaya M.K., Dogan A., Rothstein J.D., and Dempsey R.J. (1998). Traumatic brain injury down-regulates glial glutamate transporter (GLT-1 and GLAST) proteins in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 70, 2020–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ikematsu K., Tsuda R., Kondo T., and Nakasono I. (2002). The expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 2 in traumatic brain injury. Forensic Sci. International 130, 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Landeghem F.K., Weiss T., Oehmichen M., and von Deimling A. (2006). Decreased expression of glutamate transporters in astrocytes after human traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 23, 1518–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rao V.L., Dogan A., Bowen K.K., Todd K.G., and Dempsey R.J. (2001). Antisense knockdown of the glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 exacerbates hippocampal neuronal damage following traumatic injury to rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 13, 119–128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gonzalez-Gonzalez I.M., Garcia-Tardon N., Gimenez C., and Zafra F. (2008). PKC-dependent endocytosis of the GLT1 glutamate transporter depends on ubiquitylation of lysines located in a C-terminal cluster. Glia 56, 963–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang K., Taft W.C., Dixon C.E., Todaro C.A., Yu R.K., and Hayes R.L. (1993). Alterations of protein kinase C in rat hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 10, 287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Conrad K.L., Ford K., Marinelli M., and Wolf M.E. (2010). Dopamine receptor expression and distribution dynamically change in the rat nucleus accumbens after withdrawal from cocaine self-administration. Neuroscience 169, 182–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Szatkowski M., Barbour B., and Attwell D. (1990). Non-vesicular release of glutamate from glial cells by reversed electrogenic glutamate uptake. Nature 348, 443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Billups B. and Attwell D. (1996). Modulation of non-vesicular glutamate release by pH. Nature 379, 171–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jabaudon D., Scanziani M., Gahwiler B.H., and Gerber U. (2000). Acute decrease in net glutamate uptake during energy deprivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 5610–5615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Phillis J.W. and O'Regan M.H. (1996). Mechanisms of glutamate and aspartate release in the ischemic rat cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 730, 150–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grewer C., Gameiro A., Zhang Z., Tao Z., Braams S., and Rauen T. (2008). Glutamate forward and reverse transport: from molecular mechanism to transporter-mediated release after ischemia. IUBMB Life 60, 609–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Werner C. and Engelhard K. (2007). Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth 99, 4–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lima F.D., Souza M.A., Furian A.F., Rambo L.M., Ribeiro L.R., Martignoni F.V., Hoffmann M.S., Fighera M.R., Royes L.F., Oliveira M.S., and de Mello C.F. (2008). Na+,K+-ATPase activity impairment after experimental traumatic brain injury: relationship to spatial learning deficits and oxidative stress. Behav Brain Res. 193, 306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Katayama Y., Becker D.P., Tamura T., and Hovda D.A. (1990). Massive increases in extracellular potassium and the indiscriminate release of glutamate following concussive brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 73, 889–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okiyama K., Smith D.H., Thomas M.J., and McIntosh T.K. (1992). Evaluation of a novel calcium channel blocker, (S)-emopamil, on regional cerebral edema and neurobehavioral function after experimental brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 77, 607–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aslan A., Gurelik M., Cemek M., Goksel H.M., and Buyukokuroglu M.E. (2009). Nimodipine can improve cerebral metabolism and outcome in patients with severe head trauma. Pharmacol. Res. 59, 120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vetiska S. and Tymianski M. (2014). Neuroprotectants Targeting NMDA Receptor Signaling. In: Handbook of Neurotoxicity. Kostrzewa R.M. (ed). Springer; New York, pps. 1381–1402 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheney J.A., Brown A.L., Bareyre F.M., Russ A.B., Weisser J.D., Ensinger H.A., Leusch A., Raghupathi R., and Saatman K.E. (2000). The novel compound LOE 908 attenuates acute neuromotor dysfunction but not cognitive impairment or cortical tissue loss following traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 17, 83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hicks R.R., Smith D.H., and McIntosh T.K. (1995). Temporal response and effects of excitatory amino acid antagonism on microtubule-associated protein 2 immunoreactivity following experimental brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 678, 151–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Minger S.L., Geddes J.W., Holtz M.L., Craddock S.D., Whiteheart S.W., Siman R.G., and Pettigrew L.C. (1998). Glutamate receptor antagonists inhibit calpain-mediated cytoskeletal proteolysis in focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 810, 181–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maas A.I.R. (2000). Assessment of agents for the treatment of head injury: problems and pitfalls in trial design. CNS Drugs 13, 139–154 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ikonomidou C. and Turski L. (2002). Why did NMDA receptor antagonists fail clinical trials for stroke and traumatic brain injury? Lancet Neurol. 1, 383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marklund N. and Hillered L. (2011). Animal modelling of traumatic brain injury in preclinical drug development: where do we go from here? Br. J. Pharmacol. 164, 1207–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lau A. and Tymianski M. (2010). Glutamate receptors, neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Pflugers Arch. 460, 525–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]