Abstract

Infants born to diabetic mothers have a higher frequency of impaired neurodevelopment. The omega-3 or n-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is an important structural component of neural tissue and is critical for fetal brain development. Maternal DHA supplementation during pregnancy is linked to better infant neurodevelopment; however, maternal–fetal transfer of DHA is reduced in women with diabetes. Evidence of mechanisms explaining altered maternal–fetal DHA transfer in this population is limited. This review explores existing evidence underpinning reduced maternal–fetal DHA transfer in maternal fuel metabolism in this population. Further research is necessary to evaluate the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in modulating placental fatty acid binding and maternal–fetal DHA transfer. Considerations for clinical practice include a diet high in DHA and/or provision of supplemental DHA to obstetric diabetic patients within minimum guidelines.

Keywords: altered omega-3 transfer, diabetes, infant developmental outcomes, omega-3 fatty acids, PPAR, pregestational type 2 diabetes.

INTRODUCTION

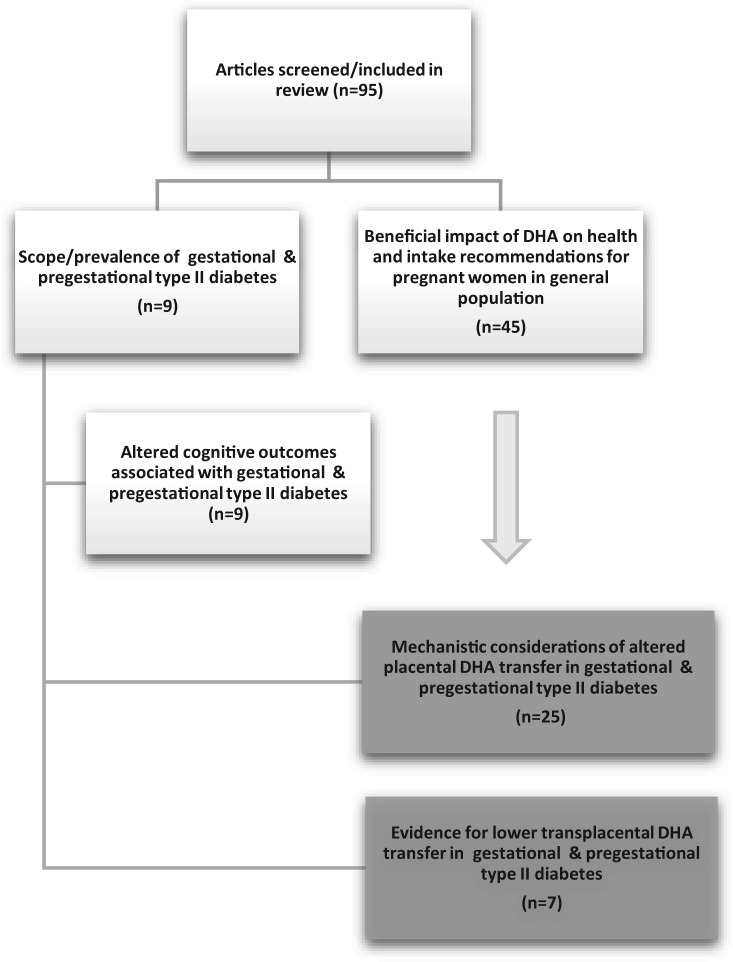

This review provides an overview of the contemporary literature on the risks of gestational diabetes to the fetus and highlights the magnitude of these risks, given that rates of gestational diabetes are rising. The importance of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to infant neurodevelopmental outcomes is presented, as are the risks associated with reduced maternal–fetal DHA transfer in pregnancies complicated by diabetes. Underlying mechanistic aberrations of placental lipid and fatty acid metabolism, as well as the potential influence of diet on epigenetic modulation of lipid pathways, are explored. Key gaps in the literature are identified, and areas of future research are proposed. To accomplish this review, the following terms were searched in the PubMed database: n-3 fatty acids, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), pregestational type 2 diabetes, altered n-3 transfer, and associated infant developmental outcomes. Articles published from 1980 through 2015 were searched to allow for the inclusion of seminal articles related to this topic. A total of 95 articles were identified and included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the literature search strategy

Gestational diabetes is a major public health concern for which a 56% relative increase in prevalence since 2000 has been recorded.1,2 Likewise, the prevalence of pregestational type 2 diabetes has increased significantly.2 Both gestational diabetes and pregestational type 2 diabetes are associated with elevated risk of perinatal mortality.3 Infants born to mothers with pregestational type 2 diabetes or gestational diabetes demonstrate lower cognitive performance,4,5 attention span, and motor function6 and face more than twice the risk of language impairment than infants born to mothers without diabetes.7 In addition, these consequences are not limited to infancy and can extend into adolescence.8 There is a lack of evidence explaining the mechanisms of these increased risks as well as little testing of potential neuroprotective interventions to avoid these diminished neurodevelopmental outcomes.9

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is a long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) derived from essential fatty acids and is a major structural component of neural tissue involved in neurotransmission and cognitive development.10–21 On average, dietary intake of DHA is profoundly below optimal levels during pregnancy,22–27 leading to supplementation recommendations,27 yet many prenatal multivitamins do not contain a preformed source of DHA. DHA supplementation in the third trimester of pregnancy, a critical window of time for fetal brain development,28,29 has the potential to confer neuroprotective properties30 and to prolong gestation, thereby preventing the need for preterm delivery.31,32 In diabetic pregnancies, an alteration in fuel metabolism is characterized by higher levels of β-hydroxybutarate,33–35 although overall oxidation is reduced.36 In addition, reduced PPAR expression is likely to be associated with alterations in placental fatty acid metabolism in diabetic pregnancies,37 thereby impacting the resultant reduced maternal–fetal transfer of DHA.38–44 Umbilical venous DHA is significantly lower in pregnancies complicated by diabetes.38–44 Limited DHA availability also induces an alteration in fatty acid biosynthesis, resulting in the production of Mead acid.45,46 There is a lack of literature evaluating whether supplementation with DHA at higher doses could effectively improve maternal–fetal DHA transfer. Further investigations are necessary to evaluate whether altered fuel metabolism is the mechanism behind inadequate DHA transfer or whether epigenetic interactions affect lipid esterification, metabolism, and utilization in the fetus. Thus, the following question guided this review: What evidence supports altered maternal–fetal placental transfer of DHA in pregnancies complicated by diabetes?

Neuroprotective role of DHA in central nervous system development

Gestation is a critical period for fetal neurodevelopment, a time when both brain cell differentiation and synapse formation occur.9,28 Nutritional deficiencies during this period can lead to disruptions in development.28 DHA, a long-chain PUFA, is a key nutrient associated with fetal neural tissue formation10 and functional outcomes.11–17 The third trimester of pregnancy is a critical window of time for maternal–fetal DHA transfer and fetal neural synthesis. Incorporation of DHA into fetal neural tissue is significantly higher than that of other key fatty acids.10 Insufficient availability of DHA has been associated with impaired neuronal development47 and decreased catecholamine biosynthesis, resulting in impaired behavioral and learning outcomes in an animal model.48 These results clearly delineate the link between DHA, brain development, and functional status. Although the benefits of DHA during pregnancy are generally well accepted, multiple research groups have demonstrated that DHA intake during pregnancy is well below 50% of the current recommended level of 200 mg/d.22–27,49 Loosemore et al.49 compared the dietary DHA intakes of a cohort with gestational diabetes with those of a control group and reported no significant difference between groups, yet intakes of both the gestational diabetes group (34.05 ± 18.02 mg/d) and the control group (67.69 ± 99.58 mg/d) were far below the recommendation for optimal pregnancy outcome.49 Furthermore, the issue of inadequate DHA intake is problematic across various ethnicities.25

Given the general concern regarding DHA deficiency, increased attention has been focused on the efficacy of maternal DHA consumption during uncomplicated pregnancies to improve developmental outcomes in infants.11–13,15–17 Colombo et al.,11 Helland et al.,12 and Judge et al.14–16 have all demonstrated a relation between improved infant cognitive function and maternal DHA supplementation. Colombo et al.11 demonstrated that infants whose mothers had greater DHA intake performed better on tasks related to habituation and attention and were less distractible at 2 years of age. Although Helland et al.12 reported no advantages in older infants following maternal cod liver oil supplementation during pregnancy and lactation, higher IQ was reported at 4 years of age compared with controls.13 Previously, Judge et al.14–16 investigated maternal DHA consumption and infant sleep organization within the first 48 hours of life, visual acuity at 4 and 6 months of age, and problem-solving abilities at 9 months of age. Benefits of n-3 intake during pregnancy have also been reported in offspring in later childhood.50,51 Campoy et al.50 reported higher mental processing in children at 6.5 years of age whose mothers were supplemented with DHA during pregnancy. Likewise, Boucher et al.51 reported better neurologic function at 11.3 years of age in a cohort of Inuit children. These findings collectively support the benefits of maternal DHA supplementation during pregnancy with regard to cognitive outcomes in offspring from infancy through childhood.

In contrast to findings supporting the neuroprotective role of DHA supplementation during uncomplicated pregnancies, Makrides et al.,17 Ramakrishnan et al.,52 and van Goor et al.53 used the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) in 18-month-old infants of women who had been supplemented with DHA during pregnancy and reported no difference in the Mental Developmental Index score between those infants and placebo groups. Colombo and Carlson54 refute the use of BSID in such studies, noting that it is a “global test designed to identify developmental delay” with assessment of “crude milestones in infancy and early childhood.” In addition, Canals et al.55 reported that the BSID was not predictive of IQ at 6 years of age for children born at term. Colombo and Carlson54 also point to seminal works in developmental psychology indicating that precisely targeted attention and information-processing tests are more predictive of cognitive function in later childhood.56–58 Given the variation in cognitive test procedures and the conflicting results, a recent meta-analysis points to a need for additional investigations.30

Association between DHA intake during pregnancy and longer gestation

Omega-3 or n-3 fatty acids are important for general health and well-being during pregnancy and are associated with longer gestation.31,32,59,60 Carlson et al.59 conducted a phase III, double-blind, randomized control trial and found that the DHA supplementation group (600 mg/d) had a longer gestation (2.9 days; P = 0.041) compared with the placebo group. Moreover, the DHA group had fewer infants born at less than 34 weeks of gestation (P = 0.025) and shorter hospital stays for infants born preterm (40.8 vs 8.9 days; P = 0.026). These findings corroborated earlier reports.31 The effects of n-3 fatty acids on length of gestation are associated with modulation of prostaglandin production and oxytocin signaling.61 This compelling evidence has implications for pregnancies complicated by pregestational type 2 diabetes, which carry an elevated risk of perinatal mortality.3

Association between gestational diabetes and risk of altered cognitive outcomes

Although maternal DHA intake has not been explicitly linked to poorer developmental outcomes in infants of mothers with diabetes, metabolic changes and fuel use disruptions associated with pregnancies complicated by diabetes are well documented.34,35,62,63 Given this evidence, there may be links between gestational diabetes and impaired processes of fetal brain development due to altered fuel utilization, a result of limited availability of critical substrates necessary for neurodevelopment. Evidence of poorer developmental outcomes in the offspring of diabetic mothers at various developmental stages, including infancy,4,44,64 toddlerhood,63 childhood,35 and adolescence,8 has been demonstrated (Table 1). Hod et al.4 investigated developmental outcomes of offspring of diabetic mothers (pregestational type 1 diabetes or pregestational type 2 diabetes) at 1 year of age. Women entered the study at 20 to 28 weeks of gestation, and hemoglobin A1C was monitored and maintained within a normal range. At 12 months of age, infants were assessed using the BSID test, which indicated that the offspring of mothers with pregestational diabetes (type 1 or type 2) had significantly lower mental and psychomotor development compared with controls. Similarly, Kowalczyk et al.62 explored the relationship between metabolic control in diabetic mothers (pregestational type 1 diabetes and gestational diabetes) and psychomotor development (Brunet-Lezine Scale) of their infants. Developmental delay was significantly higher in infants of mothers whose pregestational type 1 diabetes was well controlled during pregnancy than in infants of nondiabetic mothers.

Table 1.

Evidence of poor developmental outcomes in the offspring of diabetic mothers, according to stage of development

| Reference | Stage of development | Participants | Developmental measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hod et al. (1999)4 | Infancy | 72 participants: offspring of 31 women with PGDM and 41 nondiabetic women | BSID-II (MDI and PDI). Orientation/engagement score at 12 mo of age | MDI (91.04 PGDM vs 98.15 controls) P < 0.05 |

| PDI (85.15 PGDM vs 95.54 controls) P < 0.05 | ||||

| Orientation/engagement (41.04 PGDM vs 45.50 controls) P < 0.05 | ||||

| Zornoza-Moreno et al. (2014)44 | Infancy | 63 participants: 23 controls, 21 women with diet-controlled GDM, and 19 women with insulin-treated GDM | BSID-II (MDI and PDI). At 6 and 12 mo of age | 6 mo of age: |

| MDI (↓ in GDM + insulin group vs GDM + diet and controls) P = 0.001a | ||||

| PDI (↓ in the ODM [insulin + diet] vs controls) P = 0.002a | ||||

| 12 mo of age: NS | ||||

| Castro Conde et al. (2013)64 | Infancy | 45 participants: 23 ODM and 22 healthy newborns | Video EEG recording lasting >90 min at 48–72 h of life | Indeterminate sleep (57% ODM vs 25% controls) P < 0.001 |

| EEG findings: | ||||

| Discontinuity (2.5% ODM vs 0% controls) P = 0.044 | ||||

| δ brushes in the bursts (6% ODM vs 3% controls) P = 0.024 | ||||

| Interburst interval (0.3 s ODM vs 0 s controls) P = 0.017 | ||||

| Encoches frontales (7/h ODM vs 35/h controls) P < 0.001 | ||||

| θ/α rolandic activity (3/h ODM vs 9/h controls) P < 0.001 | ||||

| Transient sharp waves (25/h ODM vs 5/h controls | ||||

| Rizzo et al. (1991)63 | Toddlerhood | 223 participants: offspring of 89 women with PGDM, 99 women with GDM, and 35 nondiabetic women | BSID at 2 y of age and Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales at 3, 4, and 5 y of age | MDI (89 ± 18 PGDM vs 90 ± 14 GDM vs 89 ± 13 controls) NS |

| Average Stanford-Binet score (89 ± 14 PGDM vs 93 ± 13 GDM vs 92 ± 10 controls) NS | ||||

| Rizzo et al. (1997)35 | Childhood | 139 participants: 139 offspring of women with diabetes. Correlation with HbA1C | WISC-R and KTEA–Brief Form at 7–11 y of age | WISC-R correlated with HbA1C: |

| Verbal IQ: HbA1C: r = −0.18, P < 0.05 | ||||

| Full-scale IQ: HbA1C: r = −0.16, P < 0.10 | ||||

| Dahlquist & Kallen (2007)8 | Adolescence | 1 300 689 397 participants: 6397 offspring of mothers with GDM and 1 300 683 controls | Linked the Swedish Medical Birth Register with the Swedish School Mark Register (for compulsory school) | Average school marks of children: (3.13 ± 0.01, ODM vs 3.23, controls) P < 0.001 |

Abbreviations and symbols: ↓, lower; ↑, higher; BSID-II, Bayley Scales of Infant Development; EEG, electroencephalogram; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IBI, interburst interval; KTEA, Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement; MDI, mental development index; PDI, physical development index; PGDM, pregestational diabetes mellitus; ODM, offspring of diabetic mothers; NS, not significant; WISC-R, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Revised.

aMean not reported by the author.

Risks associated with diabetic pregnancy extend beyond infancy. Rizzo et al.63 investigated the impact of maternal metabolic alterations on cognitive and behavioral function in infants. Maternal glucose and lipid metabolism were monitored throughout pregnancy in 89 women with pregestational diabetes, 99 women with gestational diabetes, and 35 controls. Metabolic markers included fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1C, episodes of hypoglycemia, episodes of acetonuria, plasma β-hydroxybutarate, and free fatty acids. Markers were correlated with BSID scores at 2 years of age and with Stanford-Binet Scale scores averaged over 3, 4, and 5 years of age. Significant inverse relationships were reported between maternal β-hydroxybutarate levels in the third trimester and both the BSID and Stanford-Binet Scale scores. Free fatty acid levels were also inversely correlated with the Stanford-Binet scale scores.

Impaired language development has also been associated with diabetic pregnancies. Dionne et al.7 conducted a case–control investigation in 18-month-old to 7-year-old children, comparing language outcomes in the offspring of diabetic mothers with outcomes in controls using the McArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory, the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, and the Early Development Instrument at 72 and 84 months of age. Expressive language measures at 18, 30, and 72/84 months were significantly lower in the offspring of mothers with gestational diabetes than in controls. The authors concluded that offspring of diabetic mothers have a 2.2 times greater risk of language impairment.

The effects of diabetes in pregnancy on development of the offspring extend into adolescence.8 Dahlquist and Kallen8 conducted a population-based investigation in Sweden with 6397 children whose mothers were diagnosed with diabetes during pregnancy from 1973 to 1986 and 1 300 683 children born to nondiabetic mothers. In this investigation, data from the Swedish National School Register were used to assess academic performance. Academic grades were significantly lower in children born to diabetic mothers than in reference children, with no gender differences observed; this was also seen after adjustment for perinatal and social confounders. Children of diabetic mothers were at significantly higher risk of dropping out of compulsory education, with decreased probabilities of having passing scores in the core subjects of mathematics, English, Swedish, and sports.8

Collectively, the notion that offspring exposed to diabetes during fetal development are at risk of poorer outcomes is supported.4,8,35,44,63,64 To date, however, there is a lack of literature on links between the fetal environment, the availability of DHA to the fetus, and the functional outcomes in this high-risk population.

Lower placental DHA transfer in pregnancies complicated by diabetes

This section and the next one outline factors related to DHA availability that create an adverse fetal environment in diabetic pregnancies, potentially leading to developmental disruptions.4,40,57,62,63 Insufficient maternal DHA intake is more problematic in diabetic pregnancies because maternal–fetal DHA transfer is altered.38–44 In nondiabetic pregnancies, the placenta takes up DHA preferentially and transfers it from maternal to fetal circulation, resulting in higher venous cord blood levels compared with maternal levels.65–68 In diabetic pregnancies, maternal DHA status is unaltered69,70; however, DHA transfer from maternal to fetal circulation is altered, increasing fetal risk (Table 2).38–44 Classically, this alteration has been evidenced by the presence of Mead acid (20:3 n-9), a PUFA produced as an alternative biosynthetic pathway in situations of PUFA deficiency (i.e., DHA) that serves as a metabolic biomarker. Supplementation with fish oil in late pregnancy has been associated with significantly lower levels of Mead acid.71

Table 2.

Evidence of reduced transplacental DHA transfer in pregnancies complicated by diabetes

| Reference | No. of participants | Study design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wijendran et al. (2000)40 | 25 participants: 13 women with GDM and 12 women without diabetes | Case–control study: assessment of maternal and cord vein erythrocyte PL FA at delivery in women with GDM and in controls | DHA maternal erythrocytes: |

| (88 ± 0.26%, GDM;, 4.38 ± 0.31%, controls) P ≤ 0.05 | |||

| DHA cord vein erythrocytes: | |||

| (3.60 ± 0.44%, GDM; 5.70 ± 0.50%, controls) P ≤ 0.05 | |||

| Min et al. (2005)38 | 88 participants: 32 women with type 1 diabetes, 7 women with type 2 diabetes, and 39 women without diabetes | Case–control study: assessment of FA in maternal and cord blood samples obtained at midgestation and at delivery | Women with type 1 diabetes |

| Maternal plasma CPG DHA: | |||

| (3.7 ± 0.9%, type 1; 5.2 ± 1.6%, controls) P < 0.01 | |||

| Maternal RBC DHA: | |||

| (choline 3.4 ± 1.5%, type 1; 5.5 ± 2.2%, controls) P < 0.01 | |||

| (ethanolamine 5.9 ± 2.5%, type 1; 7.5 ± 2.5%, controls) P < 0.05 | |||

| Cord plasma CPG DHA: | |||

| (5.3 ± 1.8%, type 1; 7.1 ± 2.0%, controls) P < 0.01 | |||

| Women with type 2 diabetes | |||

| Maternal plasma CPG DHA: | |||

| (4.2 ± 0.8%, type 2; 5.2 ± 1.6%, controls) P < 0.01 | |||

| Maternal RBC DHA: | |||

| (choline 3.5 ± 1.6%, type 2; 5.5 ± 2.2%, controls) P < 0.05 | |||

| (ethanolamine 5.9 ± 2.5%, type 1; 7.5 ± 2.5%, controls) P < 0.05 | |||

| Cord plasma CPG DHA: | |||

| (5.8 ± 1.2%, type 2; 7.1 ± 2.0%, controls) P < 0.01 | |||

| Thomas et al. (2005)39 | 68 participants: 37 women with GDM and 31 women without diabetes | Case–control study: assessment of plasma FA in neonates born to women with diabetes in the third trimester of gestation | Plasma CPG DHA: |

| (5.65 ± 1.27%, GDM; 6.60 ± 1.87%, nondiabetic group) P < 0.05 | |||

| Plasma mead acid: | |||

| (0.74 ± 0.30%, GDM; 0.42 ± 0.31%, nondiabetic group) P < 0.05 | |||

| Plasma TG DHA: | |||

| (1.60 ± 1.08%, GDM; 1.67 ± 1.05% nondiabetic group) P < 0.01 | |||

| Dijck-Brouwer et al. (2005)41 | 265 participants: 258 infants born to healthy mothers and 7 infants born to mothers with diabetes | Case–control study: assessment of FA in umbilical vessels of infants | DHA deficiency index: |

| Umbilical vein [median (range): 0.94 (0.44–1.1) GDM; 0.56 (0.24–1.28) healthy group] P < 0.01 | |||

| Berberovic et al. (2013)42 | 63 participants: 32 women with type 1 diabetes and 31 healthy pregnant women | Case–control study: assessment of FA in maternal and umbilical vein serum | Umbilical vein serum: |

| AA concentration (239.7 ± 35.21 mg/L, type 1; 119.6 ± 22.89 mg/L, controls) P < 0.001 | |||

| DHA concentration (49.1 ± 4.27 mg/L, type 1; 39.6 ± 10.8 mg/L, controls) P < 0.05 | |||

| AA percentage (12.21 ± 1.64%, type 1; 11.45 ± 1.9%, controls) NS | |||

| Maternal vein serum: | |||

| AA concentration (289.9 ± 22.4 mg/L, type 1; 293.6 ± 101.0 mg/L, controls) NS | |||

| DHA concentration (103.1 ± 42.2 mg/L, type 1; 66.5 ± 11.1 mg/L, controls) P < 0.001 | |||

| Zhao et al (2014)43 | 108 participants: 24 women with GDM and 84 women without diabetes | Prospective singleton pregnancy cohort: assessment of cord plasma FA in newborns of mothers with vs without GDM | DHA (2.9 ± 0.8%, GDM; 3.5 ± 1.1%, controls) P < 0.01 |

| AA (11.3 ± 1.6%, GDM; 11.7 ± 2.0%, controls) P < 0.35 | |||

| Zornoza-Moreno et al (2014)44 | 63 participants: 23 controls, 21 women with diet-controlled GDM, and 19 women with insulin-treated GDM | Prospective cohort study: analysis of DHA percentages in maternal blood plasma collected at time of recruitment and in venous cord plasma collected within 10 min of delivery | Umbilical vein serum: |

| DHA (5.70 ± 1.19%, GDM + diet; 5.51 ± 1.08%, GDM + insulin; 6.51 ± 1.47%, controls) P < 0.05 |

Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; CPG, choline phosphoglycerides; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; FA, fatty acids; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NS, not significant; PL, phospholipid; RBC, red blood cells; TG, triglycerides.

As outlined in Table 2, 7 independent research groups have reported significantly lower maternal–fetal DHA transfer in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes, pregestational type 1 diabetes, and/or pregestational type 2 diabetes than in nondiabetic control pregnancies. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of research related to the mechanism of placental transfer of DHA. Thus, this area warrants further research to obtain evidence to support changes in clinical practice.

Mechanistic considerations of aberrant DHA metabolism in pregnancies complicated by diabetes

To date, literature providing a plausible mechanistic explanation for the reduced maternal–fetal DHA transfer observed in diabetic pregnancies is limited. Current evidence points to interruptions in placental utilization of DHA as a free fatty acid and/or impairments in fetal mobilization of DHA as a component of esterified lipids. The role of epigenetic influences in maternal transfer and fetal mobilization of DHA in diabetic pregnancy is a burgeoning area of investigation with implications for regulatory control of lipid metabolism and associated transgenerational programming.

Although a greater percentage of esterified fatty acids than free fatty acids is delivered from maternal to fetal tissue, aberrant maternal fatty acid metabolism characterized by enhanced fatty acid oxidation may explain reduced placental transfer of DHA to the developing fetus. Pregnancies complicated by pregestational type 2 diabetes (β cell dysfunction and insulin resistance) or absence of insulin in pregestational type 1 diabetes have been associated with elevated levels of β-hydroxybutarate.34,35,63 This evidence has great significance because β-hydroxybutarate is a product of ketogenesis, and elevated levels of β-hydroxybutarate indicate that fatty acids have been degraded to release energy via β-oxidation in the citric acid cycle. Hence, in this scenario, PUFAs like DHA would be utilized for energy instead of being incorporated into the fetal neural tissue. In contrast, Visiedo et al.72 reported a 30% reduction in fatty acid oxidation coupled with a 3-fold higher triglyceride concentration in women with gestational diabetes compared with controls.36,72 Given this evidence, increased fatty acid oxidation is not likely to explain the reduced maternal–fetal DHA transfer associated with diabetic pregnancy.

Since esterified fatty acids represent a larger component of lipid delivered to fetal tissue, the role of PPARs as regulators of this process needs to be considered. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are found in trophoblasts, the cells that evolve into the outer layer of the placenta and serve as the functional unit of maternal–fetal nutrient and oxygen transfer. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors control the expression of genes involved in regulating placental lipid metabolism and transfer.37 More specifically, PPARs regulate fatty acid-binding proteins as well as lipases necessary for placental fatty acid metabolism. Altered PPAR functionality may provide a compelling explanation for altered fatty acid metabolism and transfer in pregnancies complicated by diabetes. Two independent research groups have reported lower concentrations of PPARγ and PPARα proteins in placental tissues from women with gestational diabetes than in placental tissues from controls.73,74 Further work is necessary to elucidate the complex interactions of PPAR with placental fatty acid-binding protein and lipases, with particular focus on lipid utilization and programming. Placental lipases play an important role in the cleavage of esterified fatty acids for transport and use by the fetus. Magnusson et al.75 investigated lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase, two key placental lipases located in the syncytiotrophoblast at the microvillous membrane portion of the placenta. Lipoprotein lipase activity was increased in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes but was not significantly different in women with gestational diabetes compared with controls.75 In contrast, Lindegaard et al.36 reported that lipoprotein lipase activity during pregnancy was not significantly different in women with type 1 diabetes compared with controls. Furthermore, endothelial lipase activity was significantly higher in women with type 1 diabetes compared with nondiabetic controls. Radaelli et al.76 also reported increased activation of the endothelial lipase gene in pregnant women with type 1 or gestational diabetes but reduced activity of lipoprotein lipase in both the type 1 and the gestational diabetes groups. Collectively, these results support the need for further investigation of the role of placental lipoprotein lipase activity in diabetic pregnancy.36,75,76 Investigation of the impact of reduced endothelial lipase activity on placental fatty acid transport in diabetic pregnancy is also warranted.

While much has been written regarding the challenges facing offspring exposed to hyperglycemia in utero, the field of epigenetics has created a vast new frontier for researchers interested in elucidating the external effects of nutrition on gene expression.77 Epigenetics is the study of mechanisms that control how genes are switched on and off without any changes to the actual DNA of the cells.78 Fetal overnutrition and macrosomia associated with diabetic pregnancy have been associated with epigenetic changes in offspring, resulting in increased risk of obesity, metabolic syndromes, and a multitude of other disease processes.79 Dabelea and Crume80 describe the epigenetic effect of fetal overnutrition on infants, reporting altered adipocyte metabolism coupled with hyperphagia that results in a vicious cycle of obesity and diabetes. In contrast, infants who were undernourished in utero experience what Gluckman et al.81 term a “mismatch pathway.” Essentially, the undernourished fetus grows accustomed to nutrient restriction in utero; however, in the postnatal period, the infant receives a much-higher-calorie diet that disrupts the energy balance and creates epigenetic changes that predispose the infant to insulin resistance and obesity. Tollefsbol82 reported that epigenetic changes associated with nutritional status are passed on for generations through both maternal and paternal germ cells, impacting fetal gene programming for generations.

Specific to the placenta, multiple research groups have reported that epigenetic influences are associated with differential DNA methylation in diabetic pregnancy.83 Finer et al.84 compared genome-wide variation in DNA methylation in the placentae of women with gestational diabetes and of controls without gestational diabetes. They found genome-wide methylation differences between women with gestational diabetes and controls without gestational diabetes, and these differences were reported to be primarily within the first exon, with implications for placental endocytosis and DNA signaling pathways.84 Multiple abnormalities in DNA methylation in pregnancies complicated by diabetes have been reported. These abnormalities are related to the placental metabolism of lipids, including leptin and adiponectin85 and lipoprotein lipase.86 Further research is necessary to investigate the influence of epigenetic alterations in lipid pathways in diabetic pregnancy in association with the reduced maternal–fetal DHA transfer reported in this population. In summary, existing findings indicate that reduced maternal–fetal DHA transfer is present regardless of diabetic etiology and even with good glycemic control, providing compelling evidence of aberrant metabolic fuel utilization in diabetic pregnancies. Current evidence related to placental fuel utilization supports the role of low endothelial lipase activity, reduced PPAR expression, and other epigenetic interactions that influence lipid pathways as key factors that may provide a mechanistic basis for reduced maternal–fetal transfer of long-chain PUFAs in pregnancies complicated by pregestational type 2 diabetes.

CONCLUSION

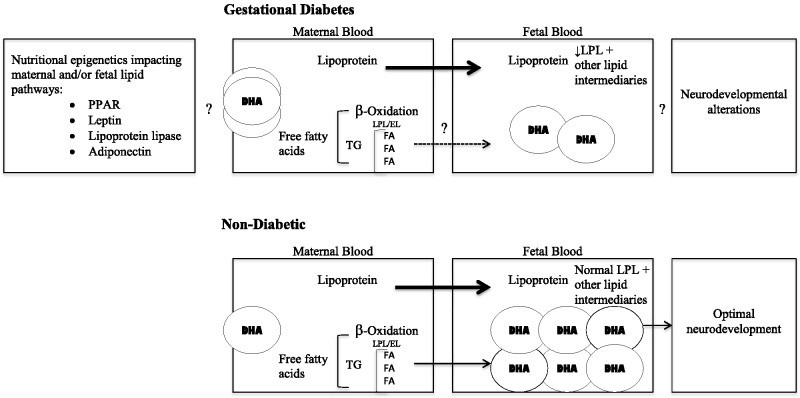

Figure 2 shows the hypothesized model of the interrelationships affecting the reduced availability of DHA to the fetus and the neurodevelopmental outcomes reported in the offspring of diabetic mothers. Offspring of diabetic mothers are at great risk for altered neurodevelopment, potentially resulting in diminished psychomotor and cognitive development that spans from infancy to adulthood. Although poor glycemic control poses a higher risk for negative developmental outcomes, the offspring of pregnant diabetic women with good maternal glycemic control are also at risk.4,34,35,63 Aberrant metabolic fuel utilization has been significantly associated, and repeatedly so, with poorer developmental outcomes in the offspring of mothers with diabetes.34,35,63

Figure 2.

Hypothesized model of the interrelationships impacting the offspring of diabetic mothers. The role of epigenetics in observed lipid pathway impairments is currently unknown with regard to DHA transfer, although the expression of key mediators involved in maternal–fetal lipid transfer has been reported. In diabetic pregnancies, alterations in the metabolic processing of free and/or esterified fatty acids are likely to be involved in the reduced availability of DHA to the fetus. Abbreviations: DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EL, endothelial lipase; FA, fatty acid; GD, gestational diabetes; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; TG, triglyceride.

DHA, an important structural component of neural tissue, is critical to brain development43,77–80 and is associated with prolonged length of gestation.31,59 The reduced maternal–fetal transfer of DHA observed in pregnancies complicated by diabetes38–40 and the associated risk of perinatal mortality3 create an adverse fetal environment and may be linked mechanistically to the metabolic disturbances associated with diabetes in pregnancy. Compounding the problem of decreased maternal–fetal DHA transfer, DHA intake during pregnancy is often far below recommended levels in the general population,22,26 further raising concern about the neurodevelopment of the offspring in this high-risk group. Increased maternal DHA intake during pregnancy has been linked to better developmental outcomes in the general population,11,13,15,16 and these findings indicate maternal DHA supplementation is beneficial to cognitive outcomes in infants. Further work is necessary to investigate if supplementation with higher levels of DHA can modulate observed epigenetic influences imposed by diabetes in pregnancy and ultimately improve DHA transfer from mother to the developing fetus.

Diabetes is associated with impaired incorporation of the choline and methyl groups in the production of phosphatidylcholine, and impairments in phosphatidylcholine production may impede the transport of maternal DHA to the placenta.87 Further research elucidating the role of PPAR and other epigenetic alterations in placental lipid metabolism and fetal programming related to lipid disorders and cardiovascular disease risk is also warranted, given that insulin resistance associated with pregestational type 2 diabetes is related to the upregulation of inflammatory pathways.88 More specifically, upregulation of interleukins, leptin, and tumor necrosis factor-α has been reported.89,90 Given the placenta’s greater affinity for DHA over other fatty acids, it is not surprising that DHA has been associated with increased expression of the placental fatty acid-binding proteins.91 It is not known whether inflammation interferes epigenetically with lipid pathways involved in the esterification and transport of DHA. In contrast, multiple markers of inflammation have been associated with the anti-inflammatory action of n-3 fatty acid supplementation, and thus further investigation of the influence of inflammation on placental epigenetic regulation of maternal–fetal fatty acid transport is warranted.92,93

Further research is necessary to determine the role of DHA as an inflammatory modulator and to establish whether DHA dose can override the reported placental epigenetic alterations in lipid pathways associated with diabetic pregnancy. In the meantime, the literature demonstrates that it is prudent to ensure that pregnant patients with pregestational type 2 diabetes are consuming DHA at the recommended dosage of 200 mg/d.94,95

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr Carol Lammi-Keefe for her team leadership in earlier research projects leading to this review.

Funding/support. Thank you to the University of Connecticut School of Nursing, Center for Nursing Scholarship, for providing resources in support of this manuscript. No external funding was provided.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

References

- 1.Lawrence JM. Women with diabetes in pregnancy: different perceptions and expectations. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correa A, Bardenheier B, Elixhauser A, et al. Trends in prevalence of diabetes among delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1993–2009. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:635–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balsells M, Garcia-Patterson A, Gich I, et al. Maternal and fetal outcome in women with type 2 versus type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4284–4291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hod M, Levy-Shiff R, Lerman M, et al. Developmental outcome of offspring of pregestational diabetic mothers. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1999;12:867–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy-Shiff R, Lerman M, Har-Even D, et al. Maternal adjustment and infant outcome in medically defined high-risk pregnancy. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:93–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ornoy A, Wolf A, Ratzon N, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at early school age of children born to mothers with gestational diabetes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;81:10–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dionne G, Boivin M, Séguin JR, et al. Gestational diabetes hinders language development in offspring. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlquist G, Kallen B. School marks for Swedish children whose mothers had diabetes during pregnancy: a population-based study. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1862–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnier C. Evaluation of early stimulation programs for enhancing brain development. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clandinin MT, Chappell JE, Leong S, et al. Intrauterine fatty acid accretion in infant brain: implication for fatty acid requirements. Early Hum Dev. 1980;4:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo J, Kannass KN, Shaddy DJ, et al. Maternal DHA and the development of attention in infancy and toddlerhood. Child Dev. 2004;75:1254–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helland IB, Saugstad OD, Smith L, et al. Similar effects on infants of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids supplementation to pregnant and lactating women. Pediatrics. 2001;108:82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helland IB, Smith L, Saarem K, et al. Maternal supplementation with very-long-chain n-3 fatty acids during pregnancy and lactation augments children's IQ at 4 years of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judge MP, Cong X, DeMare CI, et al. Maternal consumption of a DHA-containing functional food benefits infant sleep patterning: an early neurodevelopmental measure. Early Hum Dev. 2011;88:531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judge MP, Harel O, Lammi-Keefe CJ. A docosahexaenoic acid-functional food during pregnancy benefits infant visual acuity at four but not six months of age. Lipids. 2007;42:117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Judge MP, Harel O, Lammi-Keefe CJ. Maternal consumption of a DHA-functional food during pregnancy: comparison of infant performance on problem-solving and recognition memory tasks at 9 months of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1572–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makrides M, Gibson RA, McPhee AJ, et al. Effect of DHA supplementation during pregnancy on maternal depression and neurodevelopment of young children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1675–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers LK, Valentine CJ, Keim SA. DHA supplementation: current implications in pregnancy and childhood. Pharmacol Res. 2013;70:13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joffre C, Nadjar A, Lebbadi M, et al. n-3 LCPUFA improves cognition: the young, the old and the sick. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2014;91:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brenna JT, Carlson SE. Docosahexaenoic acid and human brain development: evidence that a dietary supply is needed for optimal development. J Hum Evol. 2014;77:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssen CI, Zerbi V, Mutsaers MP, et al. Impact of dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on cognition, motor skills and hippocampal neurogenesis in developing C57BL/6J mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26:24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denomme J, Stark KD, Holub BJ. Directly quantitated dietary (n-3) fatty acid intakes of pregnant Canadian women are lower than current dietary recommendations. J Nutr. 2005;135:206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innis SM, Elias SL. Intakes of essential n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids among pregnant Canadian women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Judge MP, Loosemore ED, deMare CI, et al. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) intake in pregnant women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003:103(suppl 9):167. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Judge MP, Loosemore ED, Farkas SL, et al. Dietary DHA intake across four ethnic groups. FASEB J. 2003;17:71–72. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis NM, Widga AC, Buck JS, et al. Survey of omega-3 fatty acids in diets of midwest low-income pregnant women. J Agromed. 1995;2:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koletzko B, Lien E, Agostoni C, et al. The roles of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy, lactation and infancy: review of current knowledge and consensus recommendations. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gluckman PD, Cutfield W, Hofman P, et al. The fetal, neonatal and infant environments – the long-term consequences for disease risk. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rees A, Sirois S, Wearden A. Maternal docosahexaenoic acid intake levels during pregnancy and infant performance on a novel object search task at 22 months. Child Dev. 2014;85:2131–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gould JF, Smithers LG, Makrides M. The effect of maternal omega-3 (n-3) LCPUFA supplementation during pregnancy on early childhood cognitive and visual development: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:531–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smuts CM, Borod E, Peeples JM, et al. High-DHA eggs: feasibility as a means to enhance circulating DHA in mother and infant. Lipids. 2003;38:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velzing-Aarts FV, van der Klis FR, van der Dijs FP, et al. Effect of three low-dose fish oil supplements, administered during pregnancy, on neonatal long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status at birth. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2001;65:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mead JF. Lipid metabolism. Ann Rev Biochem. 1963;32:241–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rizzo TA, Dooley SL, Metzger BE, et al. Prenatal and perinatal influences on long-term psychomotor development in offspring of diabetic mothers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1753–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rizzo TA, Metzger BE, Dooley SL, et al. Early malnutrition and child neurobehavioral development: insights from the study of children of diabetic mothers. Child Dev. 1997;68:26–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindegaard ML, Damm P, Mathiesen ER, et al. Placental triglyceride accumulation in maternal type 1 diabetes is associated with increased lipase gene expression. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2581–2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gil-Sánchez A, Demmelmair H, Parrilla JJ, et al. Mechanisms involved in the selective transfer of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids to the fetus. Front Genet. 2011;2:57 doi:10.3389/fgene.2011.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Min Y, Lowy C, Ghebremeskel K, et al. Unfavorable effect of type 1 and type 2 diabetes on maternal and fetal essential fatty acid status: a potential marker of fetal insulin resistance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1162–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas BA, Ghebremeskel K, Lowy C, et al. Plasma fatty acids of neonates born to mothers with and without gestational diabetes. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;72:335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wijendran V, Bendel RB, Couch SC, et al. Fetal erythrocyte phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids are altered in pregnancy complicated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Lipids. 2000;35:927–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dijck-Brouwer DA, Hadders-Algra M, Bouswstra H, et al. Impaired maternal glucose homeostasis during pregnancy is associated with low status of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCP) and essential fatty acids (EFA) in the fetus. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73:85–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berberovic E, Ivanisevic M, Juras J, et al. Arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid in the blood of a mother and umbilical vein in diabetic pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1287–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao JP, Levy E, Fraser WD, et al. Circulating docosahexaenoic acid levels are associated with fetal insulin sensitivity. PLoS One. 2014;9:85054 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zornoza-Moreno M, Fuentes-Hernández S, Carrión V, et al. Is low docosahexaenoic acid associated with disturbed rhythms and neurodevelopment in offsprings of diabetic mothers? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benatti P, Peluso G, Nicolai R, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids: biochemical, nutritional and epigenetic properties. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:281–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siguel EN, Chee KM, Gong JX, et al. Criteria for essential fatty acid deficiency in plasma as assessed by capillary column gas-liquid chromatography. Clin Chem. 1987;33:1869–1873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Auestad N, Innis SM. Dietary n-3 fatty acid restriction during gestation in rats: neuronal cell body and growth-cone fatty acids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:312S–314S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeuchi T, Fukumoto Y, Harada E. Influence of a dietary n-3 fatty acid deficiency on the cerebral catecholamine contents, EEG and learning ability in rat. Behav Brain Res. 2002;131:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loosemore ED, Judge MP, Lammi-Keefe CJ. Dietary intake of essential and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy. Lipids. 2004;39:421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campoy C, Escolano-Margarit MV, Ramos R, et al. Effects of prenatal fish-oil and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate supplementation on cognitive development of children at 6.5 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1880S–1888S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boucher O, Burden MJ, Muckle G, et al. Neurophysiologic and neurobehavioral evidence of beneficial effects of prenatal omega-3 fatty acid intake on memory function at school age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1025–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramakrishnan U, Stinger A, DiGirolamo AM, et al. Prenatal docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and offspring development at 18 months: randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120065 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Goor SA, Dijck-Brouwer DA, Erwich JJ, et al. The influence of supplemental docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acids during pregnancy and lactation on neurodevelopment at eighteen months. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2011;84:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colombo J, Carlson SE. Is the measure the message: BSID and nutritional interventions. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1166–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Canals J, Hernandez-Martinez C, Esparó G, et al. Neonatal behavioral assessment scale as a predictor of cognitive development and IQ in full-term infants: a 6-year longitudinal study. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:1331–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bornstein MH, Sigman MD. Continuity in mental development from infancy. Child Dev. 1986;57:251–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colombo J. Infant Cognition: Predicting Later Intellectual Functioning. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCall RB, Carriger MS. A meta-analysis of infant habituation and recognition memory performance as predictors of later IQ. Child Dev. 1993;64:57–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlson SE, Colombo J, Gajewski BJ, et al. DHA supplementation and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:808–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huffman SL, Harika RK, Eilander A, et al. Essential fats: how do they affect growth and development of infants and young children in developing countries? A literature review. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7:44–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim PY, Zhong M, Kim YS, et al. Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids alter oxytocin signaling and receptor density in cultured pregnant human myometrial smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:41708 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kowalczyk M, Ircha G, Zawodniak-Szałapska M, et al. Psychomotor development in the children of mothers with type 1 diabetes mellitus or gestational diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2002;15:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizzo T, Metzger BE, Burns WJ, et al. Correlations between antepartum maternal metabolism and intelligence of offspring. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:911–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Castro Conde JR, González González NL, González Barrios D, et al. Video-EEG recordings in full-term neonates of diabetic mothers: observational study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal. 2013;98:493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Al MD, Hornstra G, van der Schouw YT, et al. Biochemical EFA status of mothers and their neonates after normal pregnancy. Early Hum Dev. 1990;24:239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berghaus TM, Demmelmair H, Koletzko B. Essential fatty acids and their long-chain polyunsaturated metabolites in maternal and cord plasma triglycerides during late gestation. Biol Neonate. 2000;77:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hornstra G, van Houwelingen AC, Simonis M, et al. Fatty acid composition of umbilical arteries and veins: possible implication for fetal EFA-status. Lipids. 1989;24:511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Innis SM. Essential fatty acids in growth and development. Prog Lipid Res. 1991;30:39–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas B, Ghebremeskel K, Lowy C, et al. Plasma AA and DHA levels are not compromised in newly diagnosed gestational diabetic women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1492–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wijendran V, Bendel RB, Couch SC, et al. Maternal plasma phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy with and without gestational diabetes mellitus: relations with maternal factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Houwelingen AC, Sorensen JD, Hornstra G, et al. Essential fatty acid status in neonates after fish-oil supplementation during late pregnancy. Br J Nutr. 1995;74:723–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Visiedo F, Bugatto F, Sánchez V, et al. High glucose levels reduce fatty acid oxidation and increase triglyceride accumulation in human placenta. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jawerbaum A, Capobianco E, Pustovrh C, et al. Influence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activation by its endogenous ligand 15-deoxy Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2 on nitric oxide production in term placental tissues from diabetic women. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holdsworth-Carson SJ, Lim R, Mitton A, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are altered in pathologies of the human placenta: gestational diabetes mellitus, intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia. Placenta. 2010;31:222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Magnusson AL, Waterman IJ, Wennergren M, et al. Triglyceride hydrolase activities and expression of fatty acid binding proteins in the human placenta in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction and diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4607–4614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Radaelli T, Lepercq J, Varastehpour A, et al. Differential regulation of genes for fetoplacental lipid pathways in pregnancy with gestational and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;20:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simmons D. Epigenetic influences and disease. Nat Edu. 2008;1:6 http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/epigenetic-influences-and-disease-895. Accessed December 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu C, Morris JR. Genes, genetics, and epigenetics: a correspondence. Science. 2001;293:1103–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carolan-Olah M, Duarte-Gardea M, Lechuga J. A critical review. Early life nutrition and prenatal programming for adult disease. J Clin Nursing. 2015;24:3716–3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dabelea D, Crume T. Maternal environment and the transgenerational cycle of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:1849–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Low FM. The role of developmental plasticity and epigenetics in human health. Birth Defects Res. 2011;93:12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tollefsbol TO. Transgenerational epigenetics. In: Tollefsbol TO, ed. Transgenerational Epigenetics. London, UK: Elsevier; 2014:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Januar V, Desoye G, Novakovic B, et al. Epigenetic regulation of human placental function and pregnancy outcome: considerations for causal inference. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol. 2015;213(suppl):S182–S196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Finer S, Mathews C, Lowe R, et al. Maternal gestational diabetes is associated with genome-wide DNA methylation variation in placenta and cord blood of exposed offspring. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:3021–3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bouchard L, Hivert ME, Guay SP, et al. Placental adiponectin gene DNA methylation levels are associated with mothers’ blood glucose concentration. Diabetes. 2012;61:1272–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Houde AA, St-Pierre J, Hivert MF, et al. Placental lipoprotein lipase DNA methylation levels are associated with gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal and cord blood lipid profiles. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2014;5:132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huang T, Sun J, Chen Y, et al. Associations of common variants in methionine metabolism pathway genes with plasma homocysteine and the risk of type 2 diabetes in Han Chinese. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2014;7:63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jones ML, Mark PJ, Waddell BJ. Maternal dietary omega-3 fatty acids and placental function. Reproduction. 2014;147:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lappas M. The NR4A receptors Nurr1and Nur77 are increased in human placenta from women with gestational diabetes. Placenta. 2014;35:866–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Enquobahrie DA, Williams MA, Qiu C, et al. Global placental gene expression in gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Larqué E, Krauss-Etschmann S, Campoy C, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supply in pregnancy affects placental expression of fatty acid transport proteins. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Simopoulos AP. Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune disease. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Calder PC. Dietary modification of inflammation with lipids. Proc Nutr Soc. 2002;61:345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Koletzko B, Cetin I, Brenna JT, et al. Consensus statement: dietary fat intakes for pregnant and lactating women. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:873–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jordan RG. Prenatal omega-3 fatty acids: review and recommendations. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]