Abstract

Although research shows that “food parenting practices” can impact children’s diet and eating habits, current understanding of the impact of specific practices has been limited by inconsistencies in terminology and definitions. This article represents a critical appraisal of food parenting practices, including clear terminology and definitions, by a working group of content experts. The result of this effort was the development of a content map for future research that presents 3 overarching, higher-order food parenting constructs – coercive control, structure, and autonomy support – as well as specific practice subconstructs. Coercive control includes restriction, pressure to eat, threats and bribes, and using food to control negative emotions. Structure includes rules and limits, limited/guided choices, monitoring, meal- and snacktime routines, modeling, food availability and accessibility, food preparation, and unstructured practices. Autonomy support includes nutrition education, child involvement, encouragement, praise, reasoning, and negotiation. Literature on each construct is reviewed, and directions for future research are offered. Clear terminology and definitions should facilitate cross-study comparisons and minimize conflicting findings resulting from previous discrepancies in construct operationalization.

Keywords: children, eating behaviors, feeding practices, obesity.

INTRODUCTION

Data from many developed parts of the world, including Australia,1 Europe,2 and North America,3,4 consistently demonstrate that children’s dietary intakes fail to meet guidelines. For example, Kirkpatrick et al.3 found that very few children and adolescents in the United States consume recommended intakes of whole grains (<1%), vegetables (7%), fruit (29%), and milk (37%), and most exceed recommended limits for solid fats (97%) and added sugars (90%). Children’s dietary intakes and eating behaviors are influenced by a multitude of interacting factors. Davison and Birch5 and, more recently, Harrison et al.6 used the Ecological Systems Theory to identify the variety of determinants of children’s weight-related behaviors, including diet. Their models recognize multiple levels of influence, including community and society, family and home, and child-specific characteristics.

The home environment plays a particularly important role in shaping children’s habits, including eating behaviors. Parents, as key gatekeepers, strongly influence the home’s physical and social environment through their behaviors. Over 70 years of general parenting research has helped identify numerous ways that parent behaviors and parent–child interactions influence children’s physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development.7–10 These behaviors are often discussed in terms of “parenting style” and “parenting practices.” Parenting style refers to the emotional climate of the parent–child relationship. Levels of warmth and responsiveness compared with control and demandingness are used to categorize parents into 1 of 4 styles: authoritative (high warmth, high control), authoritarian (low warmth, high control), indulgent (high warmth, low control), and uninvolved (low warmth, low control).7 Parenting practices refer to the behaviors or actions (intentional or unintentional) performed by parents for child-rearing purposes that influence their child’s attitudes, behaviors, or beliefs.

While there is a rich foundation of literature about general parenting practices, Costanzo and Woody11 recognized that parenting behavior can vary across situations (i.e., domain-specific parenting) and argued that parents’ style and practices across different contexts (e.g., homework, screen media use, and feeding) should be assessed separately. Following this suggestion, child nutrition researchers have begun studying feeding-specific styles and practices and their relationships with child health status and obesity risk.12,13 In this article, these practices are referred to as “food parenting practices.” This label does not differentiate between maternal and paternal practices, but refers to them collectively. However, most research to date has focused on the practices of mothers.

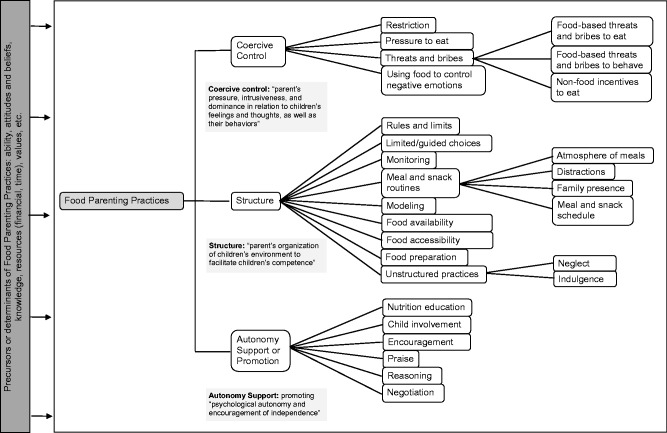

Understanding the relationship between food parenting practices and children’s dietary intakes within the dynamic context of the family is a challenging endeavor, one that is further complicated by inconsistencies in terminology and lack of clear definitions used to describe these parenting behaviors.14 Inconsistencies may be due in part to the rapid growth in this research area over the past 30 years.13 Work performed simultaneously by different research groups, without a foundation of clearly defined constructs, can easily result in the emergence of disparate terminology. At the same time, nutrition guidelines that shape how parents approach child feeding have been constantly evolving,15 as illustrated by the US Dietary Guidelines. Messages in the 1980s were framed around variety and moderation, but in 1995 they were modified to emphasize balance and weight management, only to be modified again in 2005 to add emphasis on calorie control. This reframing of messages may also have influenced the use of different terminology during these years.15 Regardless of the cause, the inconsistent terminology is a hindrance to this field of research. This article brings together experts in the field to develop a comprehensive content map for food parenting practices, including clear terminology and definitions. Food parenting style is discussed where relevant, but the primary focus of the article is clarifying food parenting practices. The food parenting content map (Figure 1) should aid future research efforts by (1) offering terminology and definitions that will facilitate cross-study comparisons and (2) facilitating testing of this model across different countries and populations.

Figure 1.

Content map of food parenting practices

As shown in Figure 1, the content map identifies 3 higher-order food parenting constructs – coercive control, structure, and autonomy support – as well as specific food parenting practice subconstructs. Table 1 16–28 provides brief definitions for each construct, sample questions from existing measures, and alternate terminology that appears in the literature. In the sections below, constructs and subconstructs are more thoroughly defined, and research is briefly reviewed.

Table 1.

Food parenting practice constructs, definitions, sample items, and related terminology from the literature

| Construct | Definition | Sample items from existing measures | Other terms in the literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive control | |||

| Restriction | Parent enforces strict limitations on the child’s access to foods or opportunities to consume those foods. Typically restrictive practices are used to control child’s intake of unhealthy foods |

|

Control |

| Pressure to eat | Parent insists, demands, or physically struggles with the child in order to get the child to eat more food |

|

Insistence on eating |

|

Parent threatens to take/takes something away for misbehavior or promises/offers something to the child in return for desired behavior. Threats and bribes can be used to manage child’s behavior for the purposes of general obedience or behaviors specific to eating. Threats and bribes can be food based, but those around eating behaviors may also be nonfood based |

|

|

| Using food to control negative emotions | Parent uses food to manage or calm the child when he/she is upset, fussy, angry, hurt, or bored |

|

|

| Structure | |||

| Rules and limits | Parent sets clear expectations and boundaries regarding what, when, where, and how much his/her child should eat |

|

|

| Guided choices | Parent allows the child a choice in what he/she eats, but options from which the child must choose are determined by the parent |

|

|

| Monitoring | Parent tracks what and how much the child is eating so that he/she can make sure the child eats sufficient amounts of healthy foods and avoids overeating unhealthy foods |

|

|

|

Parent implements consistency and predictability around meals and snacks with regard to their location, timing, presence of family members, conversational tone, and presence/absence of distractions |

|

|

| Modeling | Parent purposefully demonstrates healthy food choices and eating behaviors to encourage similar behaviors in the child; or parent unintentionally exhibits unhealthy eating behaviors in front of the child |

|

|

| Food availability | The amount and types of foods that a parent brings into the home | Often assessed with checklists of common fruits and vegetables (Hearn et al. (1998)24) or high-fat and low-fat foods (Cullen et al. (2004)25) |

|

| Food accessibility | How readily accessible the parent makes healthy and unhealthy foods in the home |

|

Energy-dense food discouraging practice |

| Food preparation | The preparation and cooking methods that a parent employs when preparing meals and snacks, which may impact the healthfulness of the foods served |

|

|

| Unstructured practices | Parent allows child complete control of their eating, including timing and frequency of meals and snacks, and amount and type of foods eaten |

|

|

| Autonomy support | |||

| Nutrition education | The explanations selected may educate the child about foods’ nutritional qualities, such as the benefits of eating healthy foods or the consequences of eating unhealthy ones |

|

Teaching about nutrition |

| Child involvement | Parent actively involves the child during meal planning, grocery shopping, meal preparation, or mealtime |

|

|

| Encouragement | Parent suggests or offers specific foods to the child as a prompt for the child to eat the target foods. Parents may also command or direct their child to eat, but prompts come without a consequence for noncompliance |

|

Prompting |

| Praise | Parent provides positive reinforcement by verbally commending the child for eating specific foods or trying new foods |

|

Nontangible reward |

| Reasoning | Parent uses logic or explanations to persuade the child to change his or her eating behavior |

|

Positive persuasion |

| Negotiation | Parent engages with child to come to an agreement about what or how much the child will eat. Negotiation allows for resolution of different opinions between parent and child by finding an acceptable compromise |

|

Bargaining |

COERCIVE CONTROL

Parental control is a fundamental element in descriptions of parenting practices; however, the definition of control has varied over time and across studies, leading to some confusion about the impact of control on child development.29 The food parenting practices content map purposefully uses the term “coercive control” to highlight a specific type of control: one that reflects attempts to dominate, pressure, or impose the parents’ will upon the child.29 Coercion helps distinguish practices that use “a restrictive over-controlling intrusive autocratic style” (p. 187)30 or those that impose “considerable external pressure on the child to behave according to the parents’ desires” (p. 321).31 Coercive control can involve such parental behaviors as “physical punishment, deprivation of material objects or privileges, the direct application of force, or the threat of any of these,” (p. 286)32 as well as “control attempts that intrude into the psychological and emotional development of the child,” (p. 3296) such as guilt induction, anxiety induction, and love withdrawal.33 A common theme across these definitions is that coercion and psychological control are parent-centered strategies, meaning that they serve the parent’s goals and desires and may not take the child’s emotional or psychological needs into account.

The selection of the term “coercive control” for the content map of food parenting practices allows the isolation of specific parent-centered feeding strategies thought to have a negative impact on children’s eating behaviors and preferences from those parenting behaviors intended to structure a child’s environment to influence the child’s socialization around food. Restriction, pressure to eat, threats and bribes, and using food to control negative emotions are conceptualized as forms of coercive control. Characterizing these practices as coercive reflects their parent-centered nature, but not necessarily the motivation behind them. Whether the motivation for such practices influences children’s perceptions of practices and/or eating behaviors is unclear. Coercive control practices are differentiated from those aspects of control that take a child’s perspective and support autonomous behavior,29 which will be considered henceforth as dimensions of “structure” and “autonomy support”.

Restriction

“Restriction” involves enforcing parent-centered, authoritarian-type limits on a child’s access to foods or opportunities to consume those foods34 and is typically used with palatable foods (e.g., high-fat and high-sugar foods) rather than total caloric intake. Typically, this type of control is of an overt nature that is recognized by the child. The widespread use of the “Restriction” subscale of the Child Feeding Questionnaire16 has promoted consistency in the way restriction has been conceptualized. However, there have been recent attempts to differentiate between types of restriction. For example, parents may restrict the kinds and/or amount of foods eaten.35 Additionally, parents may overtly control what, when, where and how much their child eats, or they may covertly limit opportunities for consumption (e.g., not bringing unhealthy foods into the home).36 In the content map, this latter type of restriction would be reclassified as “Structure.” Similarly, rules about when and where the child eats also might be classified as structure, to the extent that they take the child’s needs into account. Restriction may be differentiated on the basis of parents’ motivation to either promote health or control weight.27

The content map presented here proposes another evolution in the definition of restriction that focuses on coercive practices, which involve little or no reasoning, negotiation, or opportunity for children to make choices. These kinds of restrictions include such overt parent behaviors as threats or commands; they may be guilt inducing or involve punishment; and they do not support child autonomy (i.e., volition, potential for self-regulation). Noncoercive restrictions (e.g., setting limits, monitoring intake, controlling food availability, limiting choices, reasoning with the child) are thought to be more productive practices and have been included in the content map’s “Structure” and “Autonomy Support” sections.

Most of the literature examining the relationships between restriction and children’s eating habits, particularly in longitudinal studies, suggests that restriction has a negative impact on children’s eating habits. While parents may see restriction as a straightforward method for limiting their child’s intake of unhealthy foods, several studies have found that parental restriction is positively associated with children’s desire for restricted foods,37–39 responsiveness to food,40 tendency to overeat,41 intake of snack foods,34,38,39 and adiposity.40,42–44 However, associations between restriction and children’s weight status have been less consistent.37,45–47 Such inconsistencies across studies may reflect a failure to measure more proximal outcomes of food parenting practices (e.g., children’s eating behaviors) or contextual variables that may influence the association of restrictive feeding practices with child obesity risk (e.g., availability of energy-dense foods), as well as a poor understanding of the bidirectional influence of child characteristics on parents’ use of restrictive feeding practices.48 While restriction may be counterproductive to the development of healthy eating habits, both the general parenting and feeding literature also acknowledge that “parents cannot allow children to go unrestricted” (p. 166).29 This new distinction between coercive and noncoercive types of restriction may help resolve some of these discrepant findings and allow greater understanding of the impact of such practices.

Pressure to eat

“Pressure to eat” can be defined as parents’ insistence or demands that their children eat more food, using such strategies as insisting that children clean their plates, providing repeated prompts to eat (even when the child is not hungry), or physically struggling with or forcing the child to eat. As was the case with the definition of restriction, the widespread use of the Child Feeding Questionnaire16 (specifically, the “Pressure to eat” subscale) has been very influential in how this practice has been defined. More recently, there have been efforts to distinguish between practices that pressure a child to eat more food and those that pressure a child to eat more healthy foods (e.g., fruits and vegetables).21 An important distinction for this conceptualization of pressure to eat is the use of coercive practices in which parents make demands that are not necessarily responsive to the child’s feelings or needs to become more independent and volitional with regard to eating choices. This approach allows pressure to eat to be distinguished from such positive feeding practices as encouragements and suggestions, which differ in nuances of execution, such as tone of voice, reciprocity, and responsiveness to the child.49

Historically, research has suggested a negative correlation between pressure to eat and a child’s weight status.50 However, such findings should not be interpreted to mean that pressure to eat protects against overweight. One explanation for this negative association is that parents may be more likely to use pressure when they are concerned that their child is underweight or not consuming enough food and less likely to use pressure when they are concerned their child is overweight. A recent longitudinal analysis explored this relationship using baseline data collected when children were 7–9 years old and follow-up data collected 3 years later. Results of the analysis showed that parental pressure to eat at baseline was not associated with child adiposity at follow-up (controlling for baseline adiposity).45 However, higher child adiposity at baseline was associated with a significant reduction in parental use of pressure to eat over that 3-year period.45 One potential explanation of the observed inverse relationship is that parents of overweight children use less pressure to eat in reaction to having a heavier child. Another explanation may be that such practices have desired effects in the short term (e.g., when getting a child to initially try a food) but, over time, cause children to develop aversions to healthy foods they feel forced to eat.23,51,52 The explanation may depend on the type of pressure being exerted, i.e., pressure to eat in general compared with pressure to eat healthy foods. Food aversions and intake of fruits and vegetables may be more strongly related to the use of pressure to eat healthy foods, while child weight and parental concern for underweight may be more strongly related to pressure to eat more food.

Threats and bribes

Parents may attempt to shape their children’s behaviors (around eating or general obedience) using highly desired foods as enticements. Offering of highly desired foods may be presented as a threat or a bribe (e.g., threatening to take away dessert unless the child finishes dinner, offering a child a lollipop for behaving during a doctor visit). “Rewards” has been used as a label for both of these practices. The term “rewards” also has been used to refer to parents’ attempts to manage children’s eating behaviors using nonfood-based incentives (e.g., offering a child a sticker for trying a new vegetable). Existing measures often intermingle these constructs within a single scale.19,27,53 Clear conceptualization of these unique parent behaviors requires distinctions about the behavior being targeted (eating vs obedience) and the type of incentive used (food vs nonfood).

The content map distinguishes 3 types of threats and bribes: food-based threats and bribes to eat, food-based threats and bribes to behave, and nonfood-based incentives to eat. Food-based threats and bribes are thought to potentially undermine more internal forms of motivation for eating healthy foods54 and to increase preference for the bribe food.55 Studies have shown that using food as the bribe56,57 or bribing to increase the consumption of moderately liked foods58,59 decreases liking of the target food. In addition, studies have suggested that regularly using food as a threat or a bribe to improve behavior may make it more difficult for children to form preferences for new foods through mere exposure,60 may lead to increased snack consumption,61,62 and may predict increases in body mass index (BMI) z score over time.41 In contrast, research suggests that using nonfood incentives (e.g., stickers) for eating disliked foods (e.g., broccoli) can increase both intake and preference for the target food63–65 (see Cooke et al.66 for a more thorough review). While included within threats and bribes, these nonfood incentives to eat, especially if implemented with clear rules and expectations, may reflect part of the home’s structure that is put in place to teach and reinforce desired behaviors. This is an area where better measures are needed to examine these practices and their impact more clearly and, ultimately, to determine their placement within the content map.

Using food to control negative emotions

“Using food to control negative emotions” refers to parents’ use of food to manage or calm their children when they are upset, fussy, angry, hurt, or bored, as opposed to helping children modulate emotions in other ways (e.g., providing support, assisting in coping).19,27,67 Using food to manage children’s emotions has been theorized to lead to emotional eating in the long term.68 Substantial research has addressed emotional eating, particularly among individuals with disordered eating habits.69 However, there has been less research on the long-term impacts of parents using food to help calm their children, cheer them up, or relieve boredom. There is some evidence that links soothing with food to greater emotional eating in children,41,70 but associations with child weight are mixed.27,41,53,71 It is not yet known whether the use of food to deal with key emotions (e.g., boredom) is detrimental to children’s eating habits.

STRUCTURE

“Structure” is another type of parental control, but it involves use of noncoercive practices. In the present context, “structure” has been defined as “parents’ organization of children’s environment to facilitate children’s competence” (p. 167).29 Structure, with regard to food parenting practices, encompasses parents’ consistent enforcement of rules and boundaries about eating, strategies used by parents to help their children learn and maintain certain dietary behaviors, and the parents’ physical organization of their children’s food environment. Structure includes practices such as rules and limits, limited or guided choices, monitoring, creation of meal- and snack-time routines, role modeling, home food availability and accessibility, food preparation methods, and unstructured practices. While many of the constructs within structure have been addressed in the research literature, they have often been intermingled with more coercive practices.

Rules and limits

“Rules and limits” clarify parents’ expectations regarding what, when, where, and how much their children should eat. Rules can address a variety of issues around children’s eating, such as what types of foods are encouraged or limited,72 when certain foods can be eaten (e.g., appropriate foods for meals or snacks, weekends vs weekdays, special occasions), where meals and snacks can be eaten, or how much food can or should be eaten (e.g., limits on unhealthy foods, minimal expectations for eating healthy foods).73 Rules may also address eating in different contexts (e.g., meals eaten with the family, while at school, or on special occasions).73 Current understanding of how rules and limits influence child eating behaviors has been encumbered in part by a lack of clear delineation between rules and limits and restriction. Even among studies looking specifically at rules and limits, there are inconsistent findings, with some studies suggesting that rules and limits are associated with healthier diets,72,74 higher intakes of fruits and vegetables,75 and lower intakes of snacks76 and sugary beverages.73,77–79 Others show different associations across various dietary components (e.g., significant associations between rules and intake of unhealthy foods such as chips, but not of healthy foods),74,76 and still others find no associations with diet.80 Clear differentiation between rules and limits and restriction may help resolve these discrepant findings and enhance the current understanding of the impact of these unique practices. Additionally, it is likely that the way rules are set, communicated, and applied plays a crucial role in their impact on the child’s food intake. Therefore, it would be helpful to better understand how general parenting style and rules and limits might interact to influence the child’s diet. Furthermore, the long-term impact of having established rules should be explored to see if rules eliminate or reduce the need for parents to use such less productive practices as coercive control because there are rules in place to handle those situations.

Limited or guided choices

“Limited or guided choices” is a means for parents to give their child some control over what he or she eats, but in a way that is controlled or guided according to what the parent thinks is appropriate (e.g., based on the child’s developmental stage or nutritional needs). The options offered by the parent, from which the child must select, are limited to what the parent considers acceptable. The amount of choice a parent allows a child to have over what, when, and how much he or she eats could be envisioned on a continuum. At one end, the parent uses coercive control and gives the child no input, and at the other end the parent is very lax and permissive and completely relinquishes control to the child. Evidence suggests that both extremes have a negative impact on child diet.81,82 The proposed content map presents “limited or guided choices” as a discrete practice, one that represents a balance or sharing of control and decision-making between the parent and child. The challenge for existing measures is to capture this balance. For example, measures may need to include such items as letting the child choose from foods served, as well as less traditional items that may be reverse scored, such as catering to child’s demands (wide choice allowed by parent) and insisting the child eat what is served (no choice allowed by parent).27,28,53 Evidence to date generally has not demonstrated a significant relationship between limited choices (as defined here) and child dietary intake, which may be due in part to the challenge in assessing this construct. What parents define as acceptable choices may also impact potential associations. If parents define acceptable choices to include both healthy and unhealthy foods, then the association with healthy eating habits in children could be obscured.

Monitoring

“Monitoring” refers to the extent to which parents engage in behaviors designed to obtain information about their children’s activities and whereabouts.83,84 Monitoring, with regard to food parenting practices, is often operationalized as the frequency with which parents “keep track” of their children’s consumption of different foods (particularly sweets, snacks, and high-fat foods).16 While most measures of monitoring operationalize this construct in a similar way, studies of the relationships between parental monitoring and children’s diet, eating habits, and weight have produced inconsistent findings. Some studies suggest that parental monitoring is associated with healthier dietary intake (e.g., more fruits, vegetables, and fiber, and fewer snacks, sweets, and sugary drinks)85–87 and fewer disordered eating behaviors.41 However, other studies have failed to show any significant associations between monitoring and children’s diet or weight.16,40,46,71,88–90 One explanation may be that there is a curvilinear relationship between parental monitoring and children’s dietary behavior; that is, monitoring may promote a healthy diet to a certain point, but too much monitoring may be counterproductive and may affect dietary behavior in a negative way.91 Children may benefit from a certain degree of age-appropriate independence and capacity to make their own choices, and the optimum level of monitoring may depend on the child’s temperament, eating style, and age. Children with more disturbed eating habits may prompt a higher degree of parental monitoring.92 For example, Gubbels et al.86 showed a positive association between monitoring and a desirable child diet, but associations did not hold true for relatively hungry children or picky eaters. Furthermore, it has been suggested that a child’s excess weight may prompt a parent’s increased use of monitoring,45,93,94 thus calling into question the directionality of the relationship.

Meal and snack routines

“Meal and snack routines” refer to the parent-created structure involving the location, timing, presence of family members, atmosphere or mood, and presence or absence of distractions during meals and snacks. Existing measures typically capture just 1 or 2 aspects of these routines, such as the frequency with which meals and snacks are eaten together as a family,95,96 the timing of meals and snacks,19,97 the presence or absence of distractions while eating (e.g., TV),98 the general atmosphere during meals,98,99 or rules and manners during meals.100 In addition, timing of meals has often been measured as part of control. The result is that there is limited evidence regarding the impact of mealtime and snack routines on child diet, eating behaviors, and weight. There is some research to suggest that family routines have an important protective influence.101 Specifically, family meals are associated with improved dietary quality among children102,103 and may protect against disordered eating behaviors among adolescents.100 In addition, a few studies have shown that, when distractions (e.g., TV during family meals) are part of the normal meal routines, children tend to have lower diet quality (e.g., fewer fruits and vegetables, more chips and soda).104,105 Meal and snack routines, as defined here, includes a variety of parent behaviors that may need further distinction to understand fully their impact on children’s dietary intake or dietary quality.

Modeling

Many researchers assess modeling by measuring parent diet or what parents eat during meals shared with children.106–109 While a recent meta-analysis found that parent and child diets are related (children tend to eat what their parents eat),110 there is growing recognition that parent diet and parent modeling are two distinct constructs.111 “Role modeling” is often used to refer to more intentional efforts whereby “parents actively demonstrate healthy eating for the child.”27 Parental role modeling includes such behaviors as eating healthy foods in front of children, including foods that may be less preferred, and showing enthusiasm for healthy foods.27,112 A recent literature review of family correlates of child and adolescent fruit and vegetable consumption highlighted that parental modeling (and parent diet) was consistently positively associated with children’s dietary intake.113 One challenge in the current literature is the focus on intentional modeling of healthy habits. While it may not be intentional, parents can (and do) model unhealthy eating behaviors. Accurate assessment of unhealthy role modeling can be challenging because of the lack of awareness of these behaviors and the greater likelihood of response bias when asking about intentional modeling of unhealthy habits. Assessment of unhealthy modeling may have to rely on the use of items about how often unhealthy foods are eaten in front of the child28,114 (more similar to parent diet) and, possibly, reverse-scored items about the intentional avoidance of eating unhealthy foods during meals eaten with the children.

Food availability

“Food availability” is defined as the presence or absence of foods in the home. Food availability practices represent ways in which parents shape the home food environment (i.e., food present in the home). Parents may use food availability to influence their child’s consumption. For example, they may avoid bringing into the home foods they prefer their child not eat, and/or make more available foods they prefer their child eat. Several food parenting practice measures include food availability28,115,116 or environment27 subscales or food checklists.24,25,117 Studies have consistently shown that the availability of fruit and vegetables predicts children’s consumption.113,118 However, there is a gap in the current literature regarding how the availability of unhealthy foods (e.g., soft drinks,119 noncore foods [fats, chips, cookies]120) impacts children’s intake of those foods.

Food accessibility

While availability and accessibility are often merged into a single construct, the content map presented here considers them separately because they may have differential effects on children’s diet and eating behaviors. “Food accessibility” refers to parental actions to control how easy or difficult it is for children to access food by themselves or with limited assistance. Such practices include behaviors such as storing unhealthy foods out of the children’s reach or keeping healthy foods out in the open (e.g., fruit bowl) or stored ready-to-eat (e.g., already washed and cut). Together with food availability, these practices largely determine the home food environment. The home food environment that parents create through food availability and accessibility is also likely to influence the use of other parenting practices. For example, if the presence or visibility of unhealthy foods (e.g., potato chips, cookies, candy) is limited, it may eliminate or reduce the need for overt restriction, excessive rules and limits, and high levels of monitoring. The constructs of food availability and food accessibility illustrate the importance of understanding how practices are used in combination and how the use of some might influence the use of others.

Food preparation

“Food preparation” refers to the methods that parents use to prepare meals as well as the frequency and amount of time parents participate in meal preparation. Food preparation includes such strategies as replacing unhealthy foods with healthier alternatives (e.g., using fruit for dessert, or offering vegetables, or yogurt instead of chips for snacks), using healthier versions of products (e.g., using low-fat milk and cheese for children 2 years and older), avoiding the addition of unhealthy seasonings (e.g., butter or margarine added to cooked vegetables), modifying foods to make them healthier (e.g., trimming visible fat from meat), purposefully including healthy foods (e.g., fruits and vegetables) in meals and snacks, and using healthy instead of unhealthy cooking techniques.121–123 The limited research in food preparation practices suggests that healthier food preparation methods are significantly and inversely correlated with children’s energy intake from fat124 and child BMI percentile.123 “Cooking from scratch” (defined as “using basic ingredients to cook a meal rather than preprepared items” [p. 270]125) has also been positively associated with child vegetable intake, while use of ready-made sauces and dishes was negatively associated with intake and liking of vegetables.125 Although pilot studies have demonstrated that teaching parents cooking skills can have a positive effect,126,127 the long-term impact of food preparation practices on the dietary habits and future cooking strategies adopted by children as they become more independent is still unknown.

Unstructured practices

“Unstructured practices” refer to a lack of parental control or minimal structure around child eating (e.g., laissez-faire or complacent practices). In the general parenting literature, this lack of control translates into practices that may be neglectful or overly indulgent.128 Examples of unstructured food parenting practices include providing no oversight, offering no guidance or direction, allowing children to make inappropriate eating decisions (e.g., types of foods eaten, eating between meals), and catering to children’s demands. While these examples demonstrate a lack of control and structure, they have different emotional tones. Lack of oversight and guidance may represent an uninvolved, disengaged, or distracted parent. Catering to children’s demands may represent an overly accommodating, indulgent, sympathetic, tolerant, or defeated parent. These kinds of practices are not well captured or distinguished in the current food parenting literature. The closest semblance of this construct in the current literature comes from research on feeding styles (i.e., parenting styles in the feeding context).129 Specifically, the indulgent style is used to characterize parents who make few demands on what or how much their children eat (low demandingness) but are very nurturing and supportive in their efforts to encourage their children’s eating (high responsiveness).129 Research suggests that this kind of indulgent feeding style is associated with children having a lower diet quality and higher weight.82,129–134 While assessment of the indulgent feeding style captures a general permissive approach to feeding, it does not articulate specific practices and does not specifically distinguish those that are unstructured.

Better measures are needed to operationalize unstructured practices in a way that effectively captures this lack of parental control and structure and helps distinguish it from simply low use of monitoring and rules and limits. A single construct may also be insufficient to capture the multiple ways that lack of structure may manifest itself in parenting practices. Given that uninvolved and indulgent practices imply different emotional tones, this construct may require further division. Once unstructured food parenting practices are well operationalized, researchers can explore how these practices may coexist and interact with other food parenting practices to influence child diet and eating habits.

AUTONOMY SUPPORT

“Autonomy support” can be challenging to conceptualize in the context of child development, largely because “autonomy” and “independence” are often used interchangeably. Certainly, autonomy support is partly about elements of independence such as offering children choices and allowing for age-appropriate independent exploration. However, based on self-determination theory,54 autonomy support can be construed in terms of supporting volition, nurturing the child’s capacity to self-regulate when the parent is not around, and helping him or her develop a sense of personal ownership and endorsement of behaviors the parent is trying to instill.135 Thus, autonomy support for dietary behavior involves the following: (1) providing sufficient structure within which the child can be involved in making food choices at a developmentally appropriate level, (2) engaging in conversations with the child about reasons for rules and boundaries regarding food, and (3) creating an emotional climate during these parent–child food interactions in which the child feels unconditionally loved, valued, and accepted by parents.29,136 Constructs that address these hallmarks of autonomy support have been studied extensively in the context of parenting practices in child feeding and include nutrition education, child involvement, encouragement, praise, reasoning, and negotiation.

Nutrition education

“Nutrition education” refers to parents’ attempts to pass along information and skills to help their children make informed choices about the foods they eat. Nutrition education should support the child’s autonomy because such information presumably guides the direction of volition, self-endorsement, and internalization of eating behaviors. Parents must adjust the messages they use to match the child’s developmental stage. In young children, nutrition education involves simple messages about which foods are healthy and will help them to grow. As children get older, messages can become more complex and incorporate more skill building, such as healthier cooking approaches. A limitation of existing measures is that they typically capture only the use of simple messages to encourage children to eat healthy foods.21,27 It may be useful for measures to also assess education about the nutritional value of foods, the role of foods in health, and hunger and fullness cues. Another challenge to the clear conceptualization of nutrition education is that other practices may be used in conjunction with nutrition education. For example, parents may offer nutrition education messages when they are reasoning with their children about what foods to eat (e.g., “You should drink your milk because it is good for your bones.”). While nutrition education is conceptualized as a distinct construct, it is important to study how it is used in combination with other practices (e.g., cluster analysis of food parenting practices). Nutrition education is a relatively new construct in the literature, and hence few studies have assessed the impact of nutrition education on child diet or weight. One cross-sectional study found a negative association between parents’ use of these nutritional statements and children’s vegetable intake, a relationship that authors hypothesized to be the result of parents’ reactions to their children’s poor eating habits.21

Child involvement

Involving a child in the planning and preparation of meals allows parents to pass down family norms and traditions, and provides an opportunity for children to become more familiar with new foods. Getting children involved in grocery shopping and meal planning often includes soliciting their opinions about what foods to buy and what to prepare for meals, as well as sharing of food decision-making. Few existing surveys assess child involvement in food or meal preparation27; often it is captured by just 1 or 2 items. In older children and adolescents, a related construct is the child’s responsibility for meal and snack preparation.106,137

Encouragement

“Encouragement” can be defined as the ways that parents try to positively, gently, and supportively inspire their children to adopt healthy eating habits or persuade them to consume healthy foods over unhealthy foods. Encouragement differs from pressure to eat, in which the parent demands the child eat more, because the tone and the intention are noncoercive. Often measures operationalize this construct by asking about general encouragement (e.g., try all foods served, taste a new food).19 The literature has fairly consistently shown a positive association between encouragement and children’s intake of fruits and vegetables.85,113,138 The role of encouragement in adolescents’ eating behavior has not been studied as extensively, perhaps in part because parents’ use of encouragement as a food parenting strategy tends to decrease as children get older.139 Intervention researchers trying to teach parents how to provide encouragement may still be challenged by this definition and need more concrete examples of what encouragement looks like. Verbal prompting and suggestions could be seen as specific strategies parents might use to provide encouragement; however, how such prompts are delivered is critical. Assertive and intrusive prompts would align more closely with pressure to eat, and such prompts have been associated with increased child weight.49 Gentle prompts, reminders, suggestions, offerings, and questions (e.g., “Do you want to try the broccoli?”) may be better examples of encouraging and supportive verbal prompts. These less directive attempts to encourage eating help create a more positive, autonomy-supportive environment that may allow prompts to be received more favorably by the child. Additionally, strategies like praise, reasoning, and negotiation (described below) may serve as specific types of encouragement and support. Understanding the impact of encouragement practices will require more deliberate conceptualization and measurement of this practice.

Praise

“Praise” can be defined as a type of positive reinforcement in which a parent provides verbal feedback to the child. Although praise is generally positive in tone, it is important to differentiate types of praise,140 as they may have differential impact on child eating. For example, drawing from the broader child development literature, process praise (e.g., praising child’s willingness to try a new food, even if it was not a preferred food) may confer positive benefits on child eating behavior. This type of praise has been found to be beneficial because children learn to attribute their accomplishments to their effort and deliberate practice. In contrast, person praise (e.g., telling a child that she is a good girl for eating vegetables) may convey conditional parent regard for the child and impede internalization of healthy eating habits.140,141 While not completely intentional, the conceptualization of praise in the food parenting literature more closely resembles process praise, in that praise refers to positive reinforcement offered by parents through verbal acknowledgement and commendation for a child for eating a specific type or quantity of food (e.g., fruits or vegetables, unfamiliar food).

Existing measures generally ask parents to report the frequency with which they praise their children for eating fruits or vegetables, eating foods given to them, trying a new food, or selecting a healthy snack.17,142 Items about praise may also be incorporated into scales assessing parental encouragement.19,114 Researchers have often studied praise as a specific type of intangible reward.66 Laboratory studies in the 1980s suggested that praise might actually decrease children’s liking of familiar (and previously liked) foods.59 However, later cross-sectional surveys showed that praise was associated with healthier eating patterns in children.17 Further, intervention studies have shown that praise can increase acceptance of new foods63,143 and predict success of child obesity treatment.144 While concern persists over the impact of praise on children’s internal motivation to eat certain foods, there is support for the idea that praise may be an effective strategy for encouraging children to consume healthy foods.66,145 The success of praise as a strategy may depend on the nature and tone of the praise (e.g., praising effort, as in “That’s great that you tried that new food,” rather than praising the individual, as in “You’re such a good boy for eating a bite of carrots.”). Future research should examine this aspect of praise more closely.

Reasoning

“Reasoning” can be defined as the ways in which a parent uses logic to persuade children to change their eating behavior. Reasoning often involves trying to convince the child of the food’s positive attributes (e.g., tastes, healthfulness) or, in the case of unhealthy foods, trying to convince them of the food’s negative attributes. Existing measures often ask about encouraging children to eat healthfully by telling them that the food tastes good, will make them healthy, smart, and strong, or is liked by their family members and friends.21,28 Vereecken et al.’s17 measure of food parenting practices illustrates how rationale can be used to encourage healthy foods or discourage unhealthy foods. Obviously, some overlap exists between reasoning and nutrition education (described above). On the basis of cross-sectional surveys, it is unclear what impact reasoning has on children’s food intake. There is some evidence that reasoning is associated with increased fruit and vegetable intake, but less evidence that it is associated with decreased sweet and snack intake.17,21,28 Direct observation of family meals has also shown that reasoning was positively associated with child compliance with parents’ requests as well as with child refusals.146 These mixed findings may be due in part to how reasoning was defined and the need to differentiate between reasoning about healthy vs unhealthy foods. It may also be influenced by the parents’ overarching parenting style and whether these reasoning techniques are used consistently.

Negotiation

“Negotiation” allows for a back-and-forth discussion between parent and child to resolve differences about the amount or type of food to be consumed by the child. Negotiation supports the child’s autonomy because parents acknowledge and respect their child’s attitudes and preferences. Negotiation is not well studied, and there are few existing measures. Some measures use a single item to assess negotiation,147 while others incorporate negotiation into scales about reasoning or rationale.17 Items capture common parent–child food-negotiation scenarios, such as tasting a food even if child does not like it, deciding how much of the food the child is allowed to eat, or identifying how much food a child is expected to eat. Some longitudinal data suggest that negotiation is associated with child fruit and vegetable intake.148

DISCUSSION

The literature about food parenting practices has been growing rapidly. However, understanding relationships between food parenting practices and child diet and eating behaviors is a complex task, which has been further complicated by a lack of clear terminology and definitions. The content map, terminology, and definitions provided here should help research groups communicate their findings more clearly. Use of common terminology and definitions will facilitate comparisons across studies and improve efficiency in research efforts. Developing this content map and briefly reviewing existing literature were the first steps toward bringing this field together; however, several considerations for future research were identified in the process.

Key issues for the content map

The definitions offered here may be useful in moving toward consensus in measurement and will need to be incorporated into new measures of food parenting practices in order to achieve this goal. The inadequacy of existing measures was noted as an issue in several practices (e.g., threats and bribes, rules and limits, limited or guided choices, meal and snack routines, unstructured practices, nutrition education, child involvement, encouragement, reasoning, and negotiation). While there has been rapid growth in existing measures, available tools are not always of the desired quality. A recent review of instruments to measure food parenting practices identified 6 critical steps in the development of measures: clear conceptualization of the intended measure (step 1), use of a systematic process for developing (step 2) and refining (step 3) the item pool, and examination of the instrument’s reliability (step 4), validity (step 5), and responsiveness (step 6).13 However, for most measures developed to date, only 2 or 3 of these critical steps were included. The field does not need more measures, it needs better measures. Moving forward, researchers must invest the time and resources needed in these 6 steps to create high-quality measures with well-defined and operationalized constructs and sound psychometric properties.

As better measures are being created, researchers should use the opportunity to test and refine the content map. A key component that needs to be tested is the categorization of specific food parenting practices into the 3 higher-order constructs. This categorization captures hypothesized similarities between different practices; however, these hypotheses should be tested. Refinement of the content map may result in consolidation of similar food parenting practices or further delineation of others. For example, the content map identifies 3 types of threats and bribes: food-based threats and bribes to eat, nonfood-based threats and bribes to eat, and food-based threats and bribes to behave. While conceptually these are separate, in practice these distinctions may or may not be useful. Furthermore, constructs, like unstructured practices, may benefit from greater specification, even beyond the current delineation, into neglect and indulgence.

Researchers have also begun to consider the use of food parenting practices around specific foods (e.g., vegetables, snacks).149 Such differentiation is interesting to consider but is not addressed in the content map presented here. It is unclear how the use of practices may vary depending on the specific foods that parents are trying to get their children to eat. Those working to develop these food-specific measures should consider how they might provide evidence to justify that food parenting practices should be conceptualized this way and to what extent these differentiations are needed. It may be sufficient to differentiate food parenting practices about healthy foods from those of unhealthy foods. The benefit of greater specificity (e.g., fruit parenting practices, vegetable parenting practices, whole-grain parenting practices) is still unclear.

Key issues for food parenting research

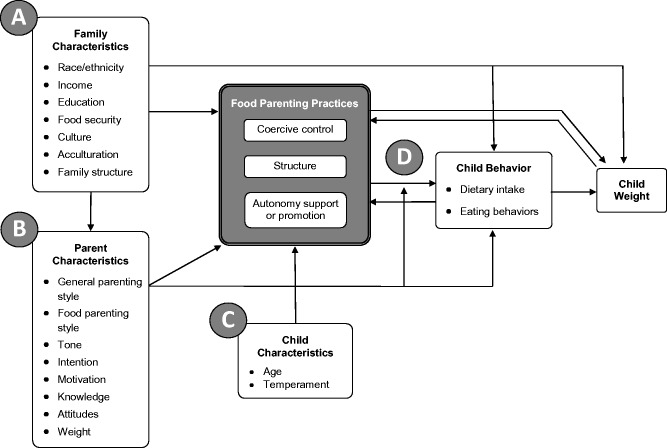

As the field continues to refine its conceptualization of food parenting practices, it will also be working to better understand the complex array of factors that predict the use of these practices and the impact of these practices on child diet and eating habits. Figure 2 presents a conceptual model that highlights key hypotheses that require greater examination. The figure is labeled A, B, C, and D to help link the discussion of key issues below to the relevant component of the conceptual model.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of food parenting practices highlighting current hypotheses in the literature. The figure is labeled with A, B, C, and D to facilitate grouping of these hypotheses. (A) hypotheses around the influence of family characteristics on food parenting practices, child diet, and child weight; (B) hypotheses around the influence of parent characteristics on food parenting practices, child diet, and child weight; (C) hypotheses around the influence of child characteristics on food parenting practices, child diet, and child weight; and (D) hypotheses around the bidirectional relationships between food parenting practices, child diet, and child weight.

Contextual factors such as family demographics may influence whether parents adopt certain food parenting practices as well as how these practices influence child diet (Figure 2A). There is a small but growing body of research examining how the use and impact of food parenting practices differ by race, ethnicity, acculturation, education, income, and food security.17,42,150–160 This research has typically focused on only a few select practices, such as restriction and pressure to eat, but results suggest that these demographic characteristics have influence and therefore warrant further study across a broader range of practices. A less researched (but still important) factor to consider is family structure. This factor can be particularly challenging because today’s families exist in multiple forms, including single- parent households (some headed by mothers, others by fathers), co-parenting arrangements, the presence of step mothers or fathers, and extended family (e.g., grandparents) and other nonbiologically related adults. The vast majority of work to date has focused on mothers, who are easier to recruit and often take the lead in feeding in many households. Research into fathers’ food parenting practices and the interaction of mothers’ and fathers’ practices is extremely limited.161–164

Additional contextual factors to consider are such parental characteristics as parenting style (both general style and feeding style), tone, intention, motivation, knowledge, attitudes, and parent weight (Figure 2B). General parenting style and feeding style are hypothesized to moderate relationships between food parenting practices and child diet, with findings from recent studies demonstrating that certain practices are more effective within the context of a positive parenting or feeding style.62,82,165–167 This critical review highlights the need for more research in this area, particularly when trying to understand how parenting style and tone influence the effectiveness of such practices as rules and limits, encouragement, praise, and reasoning. Another parental characteristic to consider is intention, which has often been overlooked in the conceptualization of practices. The current definition of food parenting practices purposefully includes both intentional and unintentional parenting behavior. Even completely unintentional practices, such as role modeling of unhealthy eating behaviors, may have a significant influence on child socialization. However, unintentional practices may pose measurement challenges due to lack of awareness or potential for response bias. In addition to intention, it is also important to consider parents’ underlying motivations behind the use of certain practices. Restriction is one of the few practices for which motivation behind the practice has been captured within the measure.27 However, as noted in the Coercive Control section, it is unclear what impact parents’ motivations have on their children or whether children are even aware of these motivations. Finally, parental knowledge and attitudes also must be considered as potential factors influencing the adoption of food parenting practices and the impact of these practices on children’s diets. As noted within the description of limited or guided choices, parental knowledge and attitudes about what is healthy will likely influence the choices offered to the child and, thereby, the child’s intake. Unfortunately, little attention has been dedicated to examining the impact of parents’ general nutrition knowledge on food parenting practices.168 One recent study found that parent knowledge was a significant predictor of intake of noncore foods but not of intake of fruits and vegetables.169 Furthermore, parent knowledge mediated the effect of authoritative feeding style on child intake of noncore foods.169

Child characteristics are yet another factor that needs to be considered when examining relationships between food parenting practices and child diet (Figure 2C). Child age and developmental stage are particularly important characteristics. Young children are extremely dependent on their adult caregivers for selecting and preparing the foods served at meal and snack times. However, as children get older and become more independent, they may need more autonomy. “Scaffolding” is the term used to capture how the level of assistance given to a child changes over time, providing more assistance and support when the child is young, and then gradually withdrawing support as the child becomes older and more able.170 For example, school-aged children are probably more likely to select after-school snacks on their own. If parents taught their children from an early age where to find and how to prepare easy fruit and vegetable snacks, consumption of fruits and vegetables would likely be higher, even when the parent is not around. The optimal pattern of food parenting practices that facilitate a healthy child diet and adoption of healthy eating habits is likely to change as a child ages, which highlights the need to examine these relationships across multiple age groups of children.

In addition to all of these contextual factors, there is also a great deal of work to be done to disentangle the complex relationships between food parenting practices and child eating behaviors (Figure 2D). Part of this complexity is that relationships may not always be linear. Limited or guided choices and monitoring are but two examples where excessively low or excessively high use of such practices may be detrimental, with best results perhaps achieved when these practices are used moderately. Such curvilinear relationships need to be explored. Another part of the complexity is that these practices are not used in isolation, and some practices may influence the need for others. The description of food availability and accessibility provides a useful illustration of this issue, noting that limiting (or not limiting) the foods brought into the home may influence parents’ need to restrict, limit, or monitor their children’s intake of unhealthy foods. A limitation of the current literature is that practices are often examined independently for correlations between specific practices and such outcomes of interest as child diet or weight. Wiggins et al.171 used taped mealtime conversations to illustrate how multiple practices may be used simultaneously, even within a brief exchange between parent and child. Cluster analysis can identify patterns in the way practices are used together, although this approach has been used infrequently.116

The field would also benefit from additional longitudinal studies examining the long-term impacts of food parenting practices as well as the bidirectional relationships between parental practices and child diet and eating behaviors. Pressure to eat and rules and limits offer interesting hypotheses about immediate vs long-term impacts of these practices. Parents who pressure their child to eat the food served may see the desired effect immediately, but over time this repeated pressure to eat disliked foods may ingrain food aversions.23,51,52 The opposite may be true for rules and limits. Newly adopted food rules may be less effective, especially if children are not accustomed to rules and limits in general. However, with consistent use over time, children may learn the rules and improve their diet. These examples illustrate how immediate and long-term effects may be very different, but longitudinal studies are required before definitive conclusions can be drawn. Longitudinal studies would also help examine the bidirectional nature of parent–child interactions around food. Parents not only influence children but also react to the behaviors and personalities of their children. This issue has been examined in a few studies, specifically around restriction, pressure to eat, and monitoring.45,172,173 These studies suggest that the practices that parents adopt are influenced by such child factors as weight, eating habits, and temperament. While the vast majority of studies to date have used cross-sectional data, there are a few cohort studies (recently completed or currently under way) that may offer good opportunities to examine some of these hypotheses.174–176 The variety of food parenting practices assessed in these studies, however, is often limited. Furthermore, intervention studies are needed to explore effective ways to change food parenting practices and their impact on child diet and eating habits.

A major strength of this critical review is that it reflects the collective thoughts of a working group of individuals with content expertise in food parenting practices who have come together to agree upon clear terminology and definitions to guide this field forward. There are, however, some limitations that are important to recognize, one of which is the lack of a systematic review. The enormous growth in this literature would make a systematic review extremely challenging. The brief review format allows critique of the literature considered to be most relevant by a diverse group of content experts. It was beyond the scope of this review to assess the scientific rigor of individual studies. Some practices are less studied than others, hence the literature referenced includes both weakly and strongly designed studies. Nevertheless, this review is able to briefly summarize current knowledge around each food parenting construct and to highlight the variety of issues that remain in this field. Another limitation of this review is the focus on parents. It is important to recognize that there are likely additional adult caregivers (e.g., grandparents, childcare providers, teachers) whose food practices also influence children’s diet and eating behaviors.

CONCLUSION

Researchers studying food parenting practices have been challenged by inconsistencies in terminology and definitions used to describe the behaviors parents use to influence their children’s eating. Consistent use of the content map described herein could facilitate consistency across studies in the way food parenting practices are named and defined. However, this review of practices has highlighted the many questions that still need to be answered in the quest to understand how food parenting practices impact children’s diets. The conceptual model provides a road map to test the many hypotheses in this area that merit study.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support. This project was supported by the Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a Prevention Research Center funded through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48-DP001944). The findings and conclusions in this journal article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Golley RK, Hendrie GA, McNaughton SA. Scores on the dietary guideline index for children and adolescents are associated with nutrient intake and socio-economic position but not adiposity. J Nutr. 2011;141:1340–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diethelm K, Jankovic N, Moreno LA, et al. Food intake of European adolescents in the light of different food-based dietary guidelines: results of the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:386–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Reedy J, et al. Income and race/ethnicity are associated with adherence to food-based dietary guidance among US adults and children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:624–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1477–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev. 2001;2:159–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison K, Bost KK, McBride BA, et al. Toward a developmental conceptualization of contributors to overweight and obesity in childhood: the six-Cs model. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maccoby E, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. In: Hetherington E, ed. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. Vol 4 New York: John Wiley; 1983:1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maccoby E. The role of parents in the socialization of children: an historical overview. Dev Psychol. 1992;28:1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Power TG, Sleddens EF, Berge J, et al. Contemporary research on parenting: conceptual, methodological, and translational issues. Child Obes. 2013;9(suppl):S87–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandara J. The typological approach in child and family psychology: a review of theory, methods, and research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6:129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costanzo P, Woody E. Domain-specific parenting styles and their impact on the child's development of particular deviance: the example of obesity proneness. J Soc Clin Psych. 1985;3:425–445. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinard CA, Yaroch AL, Hart MH, et al. Measures of the home environment related to childhood obesity: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughn AE, Tabak RG, Bryant MJ, et al. Measuring parent food practices: a systematic review of existing measures and examination of instruments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:61 doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevers DW, Kremers SP, de Vries NK, et al. Clarifying concepts of food parenting practices. A Delphi study with an application to snacking behavior. Appetite. 2014;79:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Food and Nutrition Information Center. Dietary Guidelines for Americans: A Historical Overview. Beltsville, MD: United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36:201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vereecken CA, Keukelier E, Maes L. Influence of mother's educational level on food parenting practices and food habits of young children. Appetite. 2004;43:93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vereecken C, Legiest E, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Associations between general parenting styles and specific food-related parenting practices and children's food consumption. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23:233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wardle J, Sanderson S, Guthrie CA, et al. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obes Res. 2002;10:453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Assema P, Glanz K, Martens M, et al. Differences between parents' and adolescents' perceptions of family food rules and availability. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39:84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeinstra GG, Koelen MA, Kok FJ, et al. Parental child-feeding strategies in relation to Dutch children's fruit and vegetable intake. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lytle LA, Hearst MO, Fulkerson J, et al. Examining the relationships between family meal practices, family stressors, and the weight of youth in the family. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory JE, Paxton SJ, Brozovic AM. Maternal feeding practices predict fruit and vegetable consumption in young children: results of a 12-month longitudinal study. Appetite. 2011;57:167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hearn MD, Baranowski T, Baranowsk J, et al. Environmental influences on dietary behavior among children: availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables enable consumption. J Health Educ. 1998;29:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cullen KW, Klesges LM, Sherwood NE, et al. Measurement characteristics of diet-related psychosocial questionnaires among African-American parents and their 8- to 10-year-old daughters: results from the Girls' health Enrichment Multi-site Studies. Prev Med. 2004;38(suppl):S34–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson-O'Brien R, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, et al. Fruits and vegetables at home: child and parent perceptions. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:360–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musher-Eizenman D, Holub S. Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire: validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:960–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendy HM, Williams KE, Camise TS, et al. The Parent Mealtime Action Scale (PMAS): development and association with children's diet and weight. Appetite. 2009;52:328–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grolnick WS, Pomerantz EM. Issues and challenges in studying parental control: toward a new conceptualization. Child Dev Perspect. 2009;3:165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skinner E, Johnson S, Snyder T. Six dimensions of parenting: a motivational model. Parent Sci Pract. 2005;5:175–229. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rollins BC, Thomas DL. Parental support, power, and control techniques in the socialization of children. In: Burre WR, Hill R, Nye FI, et al., eds. Contemporary Theories about the Family: Research-Based Theories. New York: Free Press; 1979:317–364. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffman ML. Moral development. In: Mussen PH, ed. Carmichael's Manual of Child Psychology. Vol 2 New York: Wiley; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barber BK. Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996;67:3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher JO, Birch LL. Restricting access to palatable foods affects children's behavioral response, food selection, and intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faith MS, Storey M, Kral TV, et al. The Feeding Demands Questionnaire: assessment of parental demand cognitions concerning parent-child feeding relations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:624–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogden J, Reynolds R, Smith A. Expanding the concept of parental control: a role for overt and covert control in children's snacking behaviour? Appetite. 2006;47:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogden J, Cordey P, Cutler L, et al. Parental restriction and children's diets: the chocolate coin and Easter egg experiments. Appetite. 2013;61:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jansen E, Mulkens S, Emond Y, et al. From the Garden of Eden to the land of plenty: restriction of fruit and sweets intake leads to increased fruit and sweets consumption in children. Appetite. 2008;51:570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jansen E, Mulkens S, Jansen A. Do not eat the red food!: Prohibition of snacks leads to their relatively higher consumption in children. Appetite. 2007;49:572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansen PW, Roza SJ, Jaddoe VW, et al. Children's eating behavior, feeding practices of parents and weight problems in early childhood: results from the population-based Generation R Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:130 doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Massey R, et al. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: a prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:24 doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardel M, Willig AL, Dulin-Keita A, et al. Parental feeding practices and socioeconomic status are associated with child adiposity in a multi-ethnic sample of children. Appetite. 2012;58:347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musher-Eizenman DR, de Lauzon-Guillain B, Holub SC, et al. Child and parent characteristics related to parental feeding practices: a cross-cultural examination in the US and France. Appetite. 2009;52:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corsini N, Danthiir V, Kettler L, et al. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Child Feeding Questionnaire in Australian preschool children. Appetite. 2008;51:474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webber L, Cooke L, Hill C, et al. Child adiposity and maternal feeding practices: a longitudinal analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1423–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson CB, Hughes SO, Fisher JO, et al. Cross-cultural equivalence of feeding beliefs and practices: the psychometric properties of the Child Feeding Questionnaire among Blacks and Hispanics. Prev Med. 2005;41:521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown KA, Ogden J, Vogele C, et al. The role of parental control practices in explaining children's diet and BMI. Appetite. 2008;50:252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carnell S, Benson L, Driggin E, et al. Parent feeding behavior and child appetite: associations depend on feeding style. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:705–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lumeng JC, Ozbeki TN, Appugliese DP, et al. Observed assertive and intrusive maternal feeding behaviors increase child adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:640–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scaglioni S, Arrizza C, Vecchi F, et al. Determinants of children's eating behavior. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6 suppl):2006S–2011S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galloway AT, Fiorito LM, Francis LA, et al. 'Finish your soup': Counterproductive effects of pressuring children to eat on intake and affect. Appetite. 2006;46:318–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batsell WR, Brown AS, Ansfield ME, et al. "You will eat all of that!" A retrospective analysis of forced consumption episodes. Appetite. 1998;38:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baughcum AE, Powers SW, Johnson SB, et al. Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001;22:391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benton D. Role of parents in the determination of the food preferences of children and the development of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:858–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mikula G. Influencing food preferences of children by “if-then” type instructions. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1989;19:225–241. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newman J, Taylor A. Effect of a means-end contingency on young children's food preferences. J Exp Child Psychol. 1992;53:200–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Birch LL, Birch D, Marlin DW, et al. Effects of instrumental consumption on children's food preference. Appetite. 1982;3:125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Birch L, Marlin DW, Rotter J. Eating as the "means" activity in a contingency: effects on young children's food preference. Child Dev. 1984;55:532–539. [Google Scholar]