Summary

Bloom-forming cyanobacteria Planktothrix agardhii and P. rubescens are regularly involved in the occurrence of cyanotoxin in lakes and reservoirs. Besides microcystins (MCs), which inhibit eukaryotic protein phosphatase 1 and 2A, several families of bioactive peptides are produced, thereby resulting in impressive secondary metabolite structural diversity. This review will focus on the current knowledge of the phylogeny, morphology, and ecophysiological adaptations of Planktothrix as well as the toxins and bioactive peptides produced. The relatively well studied ecophysiological adaptations (buoyancy, shade tolerance, nutrient storage capacity) can partly explain the invasiveness of this group of cyanobacteria that bloom within short periods (weeks to months). The more recent elucidation of the genetic basis of toxin and bioactive peptide synthesis paved the way for investigating its regulation both in the laboratory using cell cultures as well as under field conditions. The high frequency of several toxin and bioactive peptide synthesis genes observed within P. agardhii and P. rubescens, but not for other Planktothrix species (e.g. P. pseudagardhii), suggests a potential functional linkage between bioactive peptide production and the colonization potential and possible dominance in habitats. It is hypothesized that, through toxin and bioactive peptide production, Planktothrix act as a niche constructor at the ecosystem scale, possibly resulting in an even higher ability to monopolize resources, positive feedback loops, and resilience under stable environmental conditions. Thus, refocusing harmful algal bloom management by integrating ecological and phylogenetic factors acting on toxin and bioactive peptide synthesis gene distribution and concentrations could increase the predictability of the risks originating from Planktothrix blooms.

Keywords: Ecosystem engineering, Alternative stable states, Metalimnion, Co-evolution, Niche construction, HAB formation and management, Reservoirs

1. Phylogeny

The genus Planktothrix constitutes one of the early described surface bloom-forming cyanobacteria in freshwater, e.g. references in Staub (1961), although its taxonomic affiliation has undergone continuous revision and refinement. For example, for the longest period of scientific record and documentation, it has been classified under the genus Oscillatoria (Gomont, 1892) because it grows in solitary trichomes without sheaths, heterocysts, and akinetes. It has been only since 1988 that the new genus Planktothrix has been separated based on its unique ultrastructural characters as well as its life strategy (Anagnostidis and Komárek, 1988). Subsequently, the phylogenetic differentiation of this genus Planktothrix from Oscillatoria was confirmed by 16S rDNA sequencing (Wilmotte and Herdman, 2001, Suda et al., 2002, Komárek et al., 2014). Currently, the genus Planktothrix is validly described under the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) (Anagnostidis and Komárek, 1988, Gaget et al., 2015), while an attempt to validate the genus name under the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP) failed (Suda et al., 2002, Oren, 2004). More than 25 years ago, in 1989, Castenholz & Waterbury (Oren, 2004) concluded that, in the foreseeable future, the two classification systems (ICBN and ICNP) of cyanobacteria will (co-)exist. This pragmatic solution has been maintained and in the current taxonomy, the polyphasic approach including genetic, physiological, cell-structural, etc., information is routinely applied, e.g. Gaget et al. (2015). Suda et al. (2002) revised water-bloom-forming species of oscillatorioid cyanobacteria and defined three phylogenetic groups: (I) P. agardhii (Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 and P. rubescens (DeCandolle ex Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988, (II) P. pseudagardhii Suda et Watanabe, (III) P. mougeotii (Kützing ex Lemmermann) (Bory ex Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988. This phylogenetic assignment has been emended by Liu et al. (2013) describing P. spiroides Wang et Li 2013 from strains isolated from freshwater in China. Recently, Gaget et al. (2015) described three new Planktothrix species: P. paucivesiculata Gaget et al., P. tepida Gaget et al., P. serta Gaget et al. using the polyphasic approach.

2. Morphology

Filamentous cyanobacteria like Planktothrix are formed by the binary division of cells in one plane at right angles to the long axis, while the cells remain attached to each other with little or no constriction at the cross-walls. Typically, the cells are cylindrical, a little shorter than wide, and the trichomes are solitary, straight, or slightly curved. Those filaments may contain hundreds to thousands of cells, and the trichomes are a few micrometers in diameter. The length of the filaments varies, while some species (P. rubescens) grow in filaments up to a few millimeters in length. The filaments may be attenuated toward the ends or terminal cells of a trichome may be tapered, with or without a cap (calyptra). Currently, nine Planktothrix morphospecies are differentiated and categorized into three groups (Komárek and Anagnostidis, 2007): (1) morphospecies forming wavy and coiled filaments (P. cryptovaginata (Skorbatov) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988, P. planctonica (Elenkin) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988); (2) morphospecies forming rather straight filaments, not attenuated and lacking a cap (P. isothrix (Skuja) Komárek et Komarkova 2004, P. compressa (Utermöhl) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988, P. clathrata (Skuja) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988, P. suspensa (Pringsheim) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988; and (3) attenuated filaments with tapering toward the ends sometimes showing a calyptra (P. agardhii (Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988, P. rubescens (DeCandolle ex Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988, P. prolifica ([Greville] Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988).

To a certain extent, there is correspondence between the morphospecies concept (Anagnostidis and Komárek, 1988) and the polyphasic approach introduced by Suda et al. (2002). For example, the P. agardhii and P. rubescens group (sensu Suda et al., 2002) is similarly differentiated by the morphospecies concept. The species P. mougeotii (sensu Suda et al., 2002) might correspond with P. isothrix (Skuja) Komárek et Komarkova 2004 (Table 1). In contrast P. pseudagardhii (sensu Suda et al., 2002) cannot be differentiated by morphological characters only. Several species of the polyphasic taxonomy approach fit to different morphospecies (e.g. P. mougeotii vs. P. isothrix or P. compressa and P. clathrata). In the near future, it seems possible to merge the polyphasic taxonomy system with the morphospecies concept, not least because the genus Planktothrix is amenable to isolation following standard microbiological techniques (Rippka 1988), and a number of collections with clonal isolates are available: e.g. NIVA-CCA, Norwegian Institute for Water Research, Culture Collection of Algae, https://niva-cca.no/; PCC, Biological Resource Center of Institute Pasteur (CRBIP)-Pasteur Culture Collection of Cyanobacteria, http://cyanobacteria.web.pasteur.fr/; SAG, Culture Collection of Algae at Göttingen University, http://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/about-sag/184983.html; NIES-MCC, National Institute of Environmental Studies, Microbial Culture collection, http://mcc.nies.go.jp/; CCAP, Culture Collection of Algae and Protozoa, http://www.ccap.ac.uk/; CPCC, Canadian Phycological Culture Centre, https://uwaterloo.ca/canadian-phycological-culture-centre. It is noted that Planktothrix isolates from benthic habitats have been reported, which seem to be most closely related to P. mougeotii (Wood et al., 2010). From various habitats, however, P. agardhii and P. rubescens are most commonly isolated and characterized and, therefore, will be focused on in the following sections.

Table 1.

Overview of Planktothrix species differentiated either using polyphasic taxonomy or morphological characters.

| Species defined by polyphasic taxonomy | Reference | Corresp. mophospecies | Reference | Morphol. char./pigmentation1 | Lake habitat type | Geogr. distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. agardhii (Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Suda et al. (2002) | P. agardhii (Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007) | Trichomes blue-green (lacking PE), tapering towards the ends sometimes with cap, <6 μm wide | Shallow polymictic nutrient-rich | Temperate climatic zone |

| P. rubescens (DeCandolle ex Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | -”- | P. rubescens (DeCandolle ex Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007) | Trichomes reddish or pink, tapering towards the ends sometimes with cap, >6 μm wide | Deep dimictic mesotrophic | Temperate climatic zone |

| -”- | -”- | P. prolifica ([Greville]) Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007), Skulberg and Skulberg (1985) | Trichomes reddish or pink, tapering towards the ends sometimes with cap, <6 μm wide | Deep dimictic mesotrophic | Temperate climatic zone |

| P. pseudagardhii Suda et Watanabe 2002 | -”- | – | – | Similar to P. agardhii (Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Shallow or deep polymictic nutrient-rich | Sub(tropical) climatic zone |

| P. mougeotii (Kützing ex Lemmermann) comb. nov. non (Bory ex Gomont) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | -”- | P. isothrix (Skuja) Komárek et Komarkova 2004 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007) | Trichomes (dark)blue-green, cylindrical, not attenuated, cells isodiametric | Benthic (epipelic on mud) and planctic in eutrophic stagnant waters | Cosmopolitan |

| -”- | -”- | P. compressa (Utermöhl) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007) | Trichomes blue-green, cylindrical, not attenuated, finely constricted at cross walls | Shallow nutrient-rich | Germany |

| -”- | -”- | P. clathrata (Skuja) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007) | Trichomes blue–green, cylindrical, not attenuated, finely constricted at cross walls | Benthic (epipelic on mud) and planctic in eutrophic stagnant waters | Germany, Sweden, Australia |

| P. spiroides Wang et Li | Liu et al. (2013) | – | – | Trichomes blue–green (lacking PE), forming regularly loose screw-like coils, hardly attenuated at one end | Shallow polymictic nutrient-rich | Sub(tropical) climatic zone (China) |

| P. paucivesiculata Gaget et al. | Gaget et al. (2015) | – | – | Relatively low number of gas vesicles, blue–green trichomes, cell width 4–5 μm | Shallow nutrient-rich | France |

| P. tepida Gaget et al. | -”- | – | – | Trichomes blue–green, round apical cells | Fish farm pond | Central African Republic |

| P. serta Gaget et al. | -”- | – | – | Trichomes blue–green, round apical cells | Sewage treatment plant | France |

| – | – | P. suspensa (Pringsheim) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Pringsheim (1965), Komárek and Anagnostidis, 2007, D’Alelio et al., 2011 | Trichomes yellowish-green, only 2–4 μm wide | Shallow and deep | Temperate climatic zone |

| – | – | P. cryptovaginata (Skorbatov) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007) | Trichomes blue–green, usually wavy, sometimes with facultative sheaths | In littoral among stones or water plants | Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

| – | – | P. planktonica (Elenkin) Anagnostidis et Komárek 1988 | Komárek and Anagnostidis (2007) | Trichomes blue–green, irregularly wavy, | In littoral among stones or water plants | Eastern Europe and Russia |

PE, phycoerythrin.

3. Ecophysiological adaptations

Within the genus Planktothrix, it is frequently P. agardhii and P. rubescens that dominate the phytoplankton in the water column. Understanding the ecophysiological adaptations helps to explain the competitiveness and invasive ability of Planktothrix.

3.1. Buoyancy

The most successful way to overcome the tendency to sink out of the euphotic zone is to maintain a gas-filled space within the protoplast — a gas vesicle has a density of approx. one tenth that of water and thus gives the cells a lower density (Walsby, 1994). Due to the generation of polysaccharides via photosynthesis, the cellular weight increases and, due to respiration processes, the cellular weight decreases (Reynolds et al., 1987). Changes in cellular weight can be balanced via gas vesicles leading to optimal physiological conditions for the organism either on the surface or at a certain depth in the water column (Konopka et al., 1993). Already during the 1990s, gas vesicle protein genotypes, differing in gas vesicle protein size and gas vesicle strength, have been identified (Beard et al., 2000). Selective pressure on gas vesicle strength include the mixing depth during the winter (Walsby et al., 1998), and correlations between the lake depth and gas vesicle resistance to the collapse by water pressure have been suggested. The resulting hypothesis regarding selective factors influencing gas vesicle protein genetic structure in populations (Hayes et al., 2002) has been confirmed. D’Alelio et al. (2011) isolated a large number of Planktothrix strains from deep lakes in the southern Alps and reported that the fraction of isolates carrying relatively stronger gas vesicles was higher in the deep lakes where the average mixing depth during the winter exceeded one hundred meters.

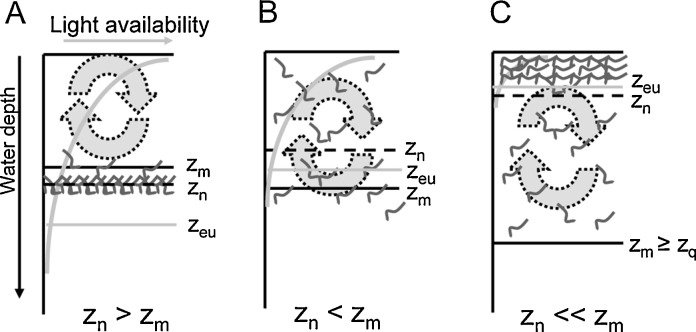

For single Planktothrix filaments, the maximum floating velocity is 10 μm s−1 or 1 m d−1 (Walsby, 2005). The formation of a layer by P. rubescens in the metalimnion (typically in a depth of 8–13 m in stratified, mesotrophic lakes of the temperate climatic zone) is the result of the slow vertical migration of buoyant filaments constantly rising and sinking as a consequence of photosynthetic assimilation. Occasionally P. rubescens filaments rise to the surface and form reddish surface blooms, which is known as the “burgundy blood phenomenon”. In order to form surface blooms, the cells need to be buoyant and the wind conditions need to be calm to allow the cells to float up. Buoyancy depends on the physiological state of the cells: it decreases under high irradiance and increases under low irradiance. Walsby et al. (2005) developed a conceptual model to explain the burgundy blood phenomenon by the occurrence of surface blooms near shallow, leeward shores arising from populations floating up in the deeper regions of the lake. The model relies on the accurate determination of the water depth where the filaments will gain neutral buoyancy (zn). For a given light attenuation in the water column, this depth can be determined under controlled conditions in the laboratory, but it also depends on other factors, such as temperature and nutrient concentrations. For P. rubescens, Walsby et al. (2004) determined that filaments will be neutrally buoyant at 6.5 μmol m−2 s−1. If zn exceeds the mixing depth (zm), the filaments will sink out of the mixed layer and stratify in the metalimnion. This happens during the spring and summer when the water body is thermally stratified and the mean daily light availability is high (Fig. 1A). During autumn, zn decreases as the daily light availability in the water column declines, while zm increases as the intensity of mixing increases. Once zm > zn, the filaments will become entrained in the mixed layer. Nonetheless, as long as the light availability is high (the euphotic zone, zeu ∼ zm), filaments will start to sink on calm days and then no water bloom can occur (Fig. 1B). With increasing zm, the light availability will decrease further as filaments are mixed to a successively greater depth, and the probability that the filaments will become buoyant increases. At a certain zm, filaments will receive such low amounts of light throughout the day (zq) that on calm days they will float up and may form a surface bloom (Fig. 1C). Since the filaments rise rather slowly, only some part of the filaments will contribute to the bloom, and this proportion of the population can be estimated using such a model (Walsby et al., 2005).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model to predict the occurrence of Planktothrix rubescens surface blooms (Walsby et al., 2004). zm, mixing depth; zn, depth in which filaments gain neutral buoyancy; zq, critical depth for buoyancy (modified from Walsby et al., 2005).

Conversely, during a seasonal study, the biomass peak of P. rubescens was found associated with the same isotherm (19.8 °C) throughout the lake suggesting that P. rubescens was passively transported in the water column, e.g. by internal waves through wind action (Cuypers et al., 2011). The same authors reported that, within a single day, the depth of the peak biomass can vary up to 10 m at a specific sampling point or between sampling stations, implying that buoyancy could not overcome internal waves inducing pronounced vertical displacements. Rather internal waves influenced the growth of P. rubescens through physical factors such as light availability or nutrients (Garneau et al., 2013). It has been suggested that such vertical displacement affects the production of Planktothrix biomass and finally horizontal patchiness (Hingsamer et al., 2014).

3.2. Light harvesting and shade tolerance

Within phytoplankton, the species P. agardhii and P. rubescens are known as the most efficient light harvesters, which is, in part, due to specific accessory pigments, the phycobilins. These pigments are bound to water soluble proteins, the phycobiliproteins, which occur in three variants with different optical properties: the blue-green allophycocyanin (APC) and phycocyanin (PC) and the red phycoerythrin (PE). Compared with other algae, these adaptations lead to more efficient light conversions since it enables harvesting light additionally in the green part of the spectrum (around 600 nm), (e.g. Reynolds, 1997, Fig. 27). Due to the low energy requirement to maintain cell metabolism, Planktothrix can sustain a relatively higher growth rate than other algae when light intensities are low (Mur et al., 1978, Van Liere et al., 1979).

Although the chromatic adaptation of Planktothrix isolates has not been observed (Skulberg and Skulberg, 1985, Suda et al., 2002), it has been shown by genome sequence comparison that a PE gene cluster has been horizontally transferred, and it resulted in red pigmentation in a strain that was otherwise more closely related to green-pigmented strains (Tooming-Klunderud et al., 2013). Similarly, within the P. agardhii and P. rubescens complex (sensu Suda et al., 2002), the PC/PE pigmentation pattern was found to be polyphyletic (Kurmayer et al., 2015) suggesting that the phycobilin pigmentation is frequently modified in response to the prevailing light absorption maxima. Nevertheless, the co-occurrence of green- and red-pigmented Planktothrix strains in the same water body has been described only occasionally (e.g. Kurmayer et al., 2011). In deep stratified lakes, the red-pigmented life form seems to outcompete the green-pigmented life form (Davis et al., 2003).

3.3. Nutrient acquisition

The availability of macronutrients, such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), have long been recognized for their key role in the ecology of phytoplankton. The P sources are restricted to the dissolved orthophosphate ions (P-PO4). Most of the N is available as atmospheric N2 while nitrate (N-NO3), nitrite (N-NO2), and ammonium (N-NH4) are dissolved in water. For phytoplankton, in general, growth constants for P vary between 20 and 200 nM for the half saturation constant (Ks), and 0.8–2 mmol P per mol of carbon (C) for Droop's minimum cell quota (q0). The growth constants for N are one order of magnitude higher, e.g. for Ks 300–3000 nM, and for q0 20–50 mmol N per mol C (e.g. in Sommer, 1994, Table 6.2; in Reynolds, 2006, pp. 151–164). Across various phytoplankton species, the Ks values and maximum uptake rates (Vmax) have been found to be similar when expressed in terms of the cell surface area or per unit of cell carbon (e.g. in Reynolds, 1997, Fig. 21; in Reynolds, 2006, Fig. 4.5). For example, when compared with green algae, the growth constants of P. agardhii on both N–NO3 and P–PO4 are in the same nanomolar range, e.g. Van Liere and Mur (1980). Since prokaryotic and eukaryotic algae are in an environment with highly variable P-PO4 concentrations, an enhanced P–PO4 affinity permits to maximize patch encounters (Jacobson and Halmann, 1982). Like other eukaryotic algae, Planktothrix excretes alkaline phosphatases allowing to use dissolved organic P in addition to soluble reactive inorganic P (Feuillade et al., 1990). The capacity to store surplus P as polyphosphate allows the cell numbers to increase 3-fold to 4-fold without the need of the uptake of additional P (Reynolds, 2006).

The cyanobacterium Planktothrix has been shown to store N intracellularly as cyanophycin (a co-polymer of aspartate and arginine) or phycocyanin (Van de Waal et al., 2010). Therefore, Planktothrix may have a competitive advantage against eukaryotic algae under N-limiting conditions even if it cannot fix atmospheric N. Finally, it has been reported that, under conditions of low light availability, the uptake of nitrogenous organic compounds (amino acids like alanine, serine, glycine, glutamine, glutamate) may contribute to the growth of P. rubescens (Krupka and Feuillade, 1988, Zotina et al., 2003, Walsby and Jüttner, 2006). The ability of P. rubescens to compete with other heterotrophic bacteria for the uptake of amino acids at environmentally relevant concentrations has been demonstrated (Feuillade et al., 1988, Salcher et al., 2013). As P. rubescens can form significantly more biomass under stratifying conditions when compared with heterotrophic bacteria in the epilimnion (Van den Wyngaert et al., 2011), a substantial part of N excreted from Planktothrix cells is possibly re-assimilated within the population.

4. Ecology and biogeography

4.1. Phytoplankton associations

The cyanobacteria P. agardhii and P. rubescens have been shown not only to survive best under self-shading conditions but also to promote these low light conditions by building up more biomass per unit of P and thus causing higher turbidity than other phytoplankton species (e.g. Scheffer et al., 1997). For example, P. agardhii generates a positive feedback loop, creating an environment in which it can hardly be outcompeted by other phytoplankton. In some regions (e.g. lowland areas of the Netherlands and Northern Germany), it perennially dominated shallow eutrophic and hypertrophic water bodies for many years (Van Liere and Mur, 1980, Mur, 1983, Rücker et al., 1997). The species P. agardhii often co-occurs with other solitary filamentous Oscillatoria-like cyanobacteria, such as Limnothrix, Planktolyngbya, and Pseudanabaena (Reynolds et al., 2002), which are characterized as successful in turbid mixed water layers under light deficient conditions. These associations are sensitive to water exchange, but not to grazing by zooplankton. Using an extensive data set (940 samples from 28 mesotrophic to hypertrophic lakes), P. agardhii frequently was found as a minor component of the phytoplankton (representing <10% of the total biovolume), but in several cases it was found to be strongly dominant (>50%); (Bonilla et al., 2012). Its biovolume contribution declined sharply along the gradient from a low to high ratio of depth of the euphotic zone to the depth of vertical mixis (1.62–3.5). The species P. agardhii further showed a sharp increase in biovolume contribution with increasing temperature (11–30 °C) and a sharp decline from 159 to 500 μg L−1 of the total P. Altogether, when the environmental conditions are optimal, P. agardhii has a high chance of dominating the phytoplankton.

The red-pigmented P. rubescens dominates in a greater water depth with higher shares of green light compared to the light conditions at the water surface. By particularly sensitive buoyancy regulation and chromatic adaptation, it can make optimal use of this low light habitat with steep chemical gradients: The plate-like layers, e.g. 1–2 m in thickness (Salcher et al., 2011), which are formed – usually on the lower border to the metalimnion during summer stratification – enables this species to monopolize limiting nutrients because individuals of the same population occurring at high cell density directly take up nutrients that are released from dead cells (Section 3.3). In addition, the increased physical stability of the water column, e.g. due to higher summer temperature in consequence to climate warming enhances vertical positioning and increases the P. rubescens seasonal growth period (e.g. Posch et al., 2012). The effective nutrient uptake strategy may be the reason why for many years deep stratified habitats dominated by P. rubescens have shown little response even to pronounced decreases of total P loading (e.g. Jacquet et al., 2005). Nevertheless, the importance of nutrient availability in the epilimnion as a consequence of deep mixing events has been highlighted particularly in the deep lakes of the Italian Alps (Salmaso, 2005). More recently, a decline of P. rubescens was attributed to the ongoing reduction in total P concentration as a key variable in bloom termination (Jacquet et al., 2014).

4.2. Geographic distribution

The cyanobacterium P. agardhii is frequently reported from the shallow lakes of the temperate climatic zone, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere (Suda et al., 2002). Although less frequently, it is also reported from the (sub)tropical regions in Morocco (Bouchamma et al., 2004), South America (Kruk et al., 2002), Australia (Baker and Humpage, 1994), and from the temperate climatic region of New Zealand (Pridmore and Etheredge, 1987). The red-pigmented P. rubescens show a more restricted pattern of geographic occurrence within the temperate climatic zone. Mass developments of the red-pigmented P. rubescens have been reported frequently over several decades but typically from deep and thermally stratified lakes and reservoirs from countries in Europe (e.g. Jacquet et al., 2005) and North America (e.g. Nürnberg and LaZerte, 2003). The species P. rubescens has also been reported from New Zealand (Pridmore and Etheredge, 1987) but not from (sub)tropical regions.

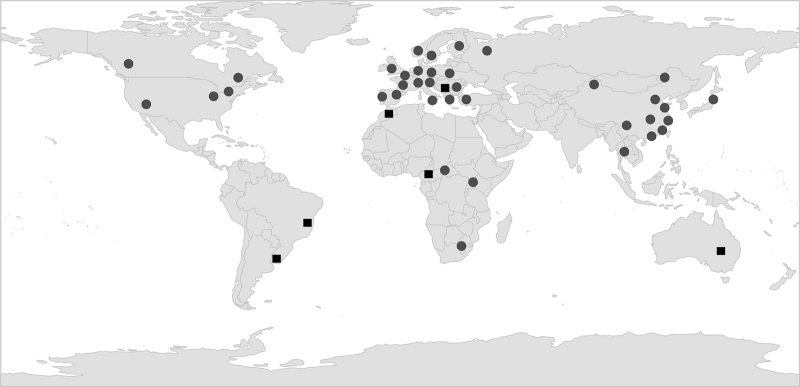

In particular, P. rubescens has a reputation of being a cold water stenotherm species (Reynolds, 1984), adapted to lower temperature (and irradiance) typically found around the thermocline of deep lakes, and unable to thrive at higher temperatures and irradiance. In contrast to other cyanobacteria, relatively low growth rates have been reported at temperatures >30 °C both for P. agardhii and P. rubescens (Suda et al., 2002). When compared with other bloom-forming cyanobacteria of the genus Microcystis, this adaptation can partly explain the underrepresentation of P. agardhii and P. rubescens in the tropical climate zone (Fig. 2). Indeed, in the temperate climatic zone, P. agardhii often forms peak biomass during the spring and autumn while Microcystis blooms during the (late) summer period (e.g. in Chu et al., 2007). Another selective factor is the high light intensity in tropical areas potentially inhibiting the global occurrence of shade-adapted species such as P. rubescens and P. agardhii (e.g. in Oberhaus et al., 2007), while Microcystis has been shown to be the most resistant to high light stress (Paerl et al., 1983). The reason why P. rubescens accumulates in the metalimnion, however, is not due to cold water adaptation, as it could easily grow under temperature and light conditions found in the epilimnion (Walsby et al., 2004). Rather, due to its red pigmentation, it can grow faster than most algae at the low irradiance found at the metalimnion of deep lakes. Thus, this is the habitat in which it can best compete with other phytoplankton species and, consequently, it is most frequently found there.

Fig. 2.

Map showing distribution of records of Planktothrix spp. either from isolation (polyphasic taxonomy, circles) or microscopical inspection (square symbols). Occurrence data from: Pridmore and Etheredge (1987), Baker and Humpage (1994), Kruk et al. (2002), Suda et al. (2002), Kemka et al. (2003), Bouchamma et al. (2004), Wood et al. (2005), Lin et al. (2010), Kurmayer et al. (2015).

Within the genus Planktothrix, distinct ecophysiological preferences for cell growth at different temperatures have been observed between P. agardhii and P. rubescens and another species P. pseudagardhii: 10–20 °C for P. agardhii and P. rubescens and 20–30 °C for P. pseudagardhii (Suda et al., 2002). Similarly, the newly described P. tepida and P. serta have a wider temperature tolerance and grow at 30 °C and 35 °C (Gaget et al., 2015). Accordingly, the natural habitats of strains assigned to P. pseudagardhii have been described mostly from the (sub)tropical climate in Thailand and China (Suda et al., 2002, Lin et al., 2010). The only exception was the P. pseudagardhii strain CW4-5 isolated from Dalai (Hulun) Lake in Inner Mongolia, which has an ice cover (Suda et al., 2002). Conradie et al. (2008) reported the isolation of P. pseudagardhii from the Vaal River system in South Africa with a water temperature ranging from 10 to 27 °C. It is concluded that the geographic occurrence of P. pseudagardhii differs climatically from the occurrence of P. agardhii and P. rubescens probably because of temperature adaptation.

5. Molecular toxicity

5.1. Toxins and the genetic basis of toxin production

The cyanobacterium Planktothrix is a prominent producer of the hepatotoxic heptapeptide MC, which is known to be an effective inhibitor of the eukaryotic protein phosphatases 1 and 2A (Metcalf and Codd, 2012). In contrast, the production of the neurotoxic compound (homo)anatoxin-a (e.g. Skulberg et al., 1992, Viaggiu et al., 2004) has been assigned to Oscillatoria or Planktothrix only occasionally. Recently, it has been shown that (homo)anatoxin-a is produced by the morphologically similar and stratifying cyanobacterium Tychonema bourellyi (Shams et al., 2015).

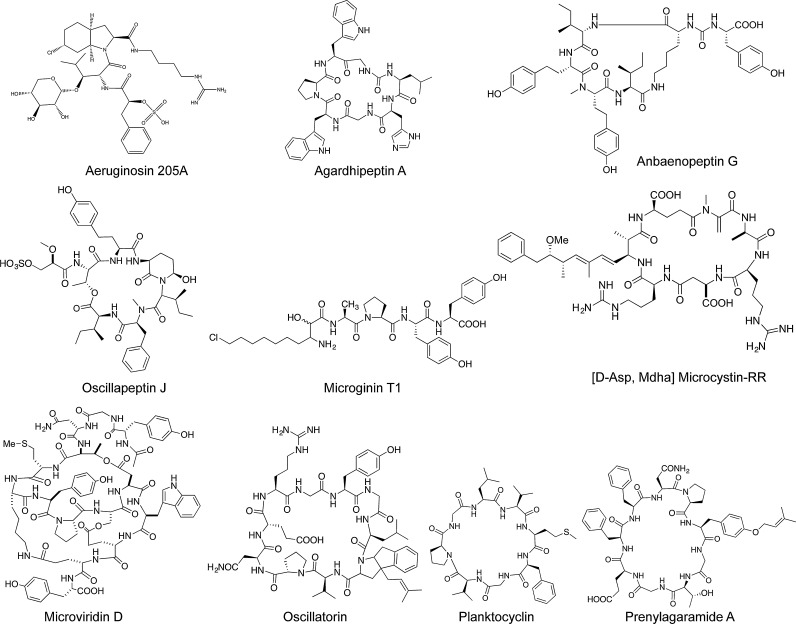

Besides the toxic MCs (e.g. Meriluoto et al., 1989, Luukkainen et al., 1993), a large number of bioactive (cyclic) oligopeptides have been identified from Planktothrix (Oscillatoria) that show the inhibition of serine proteases or other bioactive potential. All of these peptide families consist of a variable number of structural variants that differ in enzyme inhibitory activity (Fig. 3): aeruginosins (oscillarin), inhibiting trypsin and thrombin (e.g. Shin et al., 1997, Kohler et al., 2014); agardhipeptins, inhibiting plasmin (Shin et al., 1996a); anabaenopeptins (oscillamide), inhibiting carboxypeptidase A (e.g. Itou et al., 1999b) or chymotrypsin (Sano and Kaya, 1995); cyanopeptolins (oscillapeptins, planktopeptins), inhibiting tyrosinase (Sano and Kaya, 1996a), chymotrypsin, and elastase (Itou et al., 1999a, Grach-Pogrebinsky et al., 2003) or trypsin (e.g. Blom et al., 2003); microviridins, inhibiting elastase and chymotrypsin (e.g. Shin et al., 1996b); oscillatorin, inhibiting chymotrypsin (Sano and Kaya, 1996b) and planktocyclin inhibiting trypsin and chymotrypsin (Baumann et al., 2007). In addition, some other peptide families have been described to be synthesized by Planktothrix (Oscillatoria), e.g. oscillaginin (Sano and Kaya, 1997), where bioactivity has been shown for structural variants produced by other cyanobacteria, e.g. microginin inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme and leucine aminopeptidase (Kodani et al., 1999). Finally, for a third group of oligopeptides, no bioactivity could be shown, e.g. the prenylagaramides (Murakami et al., 1999), but pronounced bioactivity has been demonstrated for related peptide families, such as the aerucyclamides (e.g. Portmann et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

Overview of toxic and bioactive peptide structural variants representing peptide families isolated from Planktothrix (Oscillatoria).

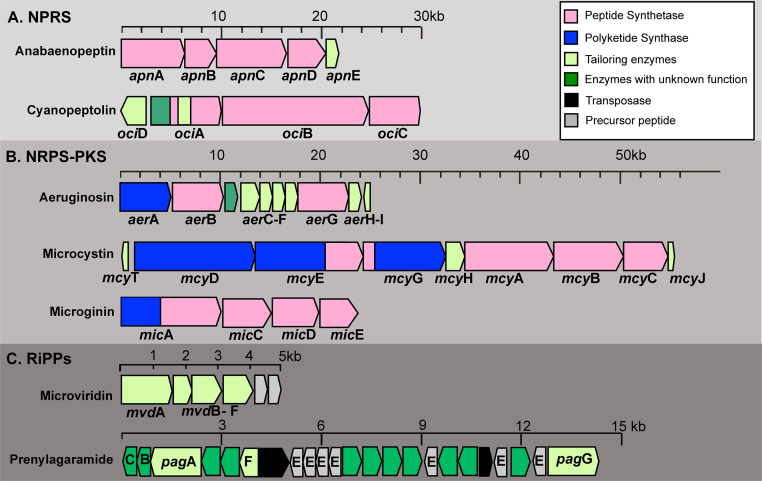

During the last decade, the synthesis pathways for all the peptide families have been elucidated (Fig. 4): MCs (Christiansen et al., 2003), aeruginosins (Ishida et al., 2007), anabaenopeptins (Christiansen et al., 2011), cyanopeptolins (Rounge et al., 2007), microviridins (Philmus et al., 2008), oscillaginin (Rounge et al., 2009), oscillatorin (Rounge et al., 2009), and prenylagaramides (Donia and Schmidt, 2011). The gene clusters for MC, aeruginosin, anabaenopeptin, cyanopeptolin, and oscillaginin typically consist of genes encoding nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) and/or polyketide synthases (PKS) that follow a stepwise synthesis pathway using either amino acids (NRPS) or acetyl-coenzyme A (PKS) as substrate. According to the thio-template mechanism (Fischbach and Walsh, 2006), the substrates are activated and condensed to the growing peptide or fatty acid like carbon chain. Such gene cluster structures have been shown to produce a large number of medicines, including antibiotics, antifungal compounds, antitumor agents, etc. and represent a promising source of new drugs (Fischbach and Walsh, 2006). Although it was anticipated that all cyclic bioactive peptides derived from bloom-forming cyanobacteria are the products of NRPS, it has been shown more recently that some representatives have a ribosomal origin (Philmus et al., 2008, Ziemert et al., 2008a, Leikoski et al., 2009). Ribosomally synthesized bioactive cyclic peptides (RiPPs) are formed through the posttranslational modification of a precursor peptide consisting of two functional subunits — a leader peptide and a core peptide. Microviridins are produced from ribosomally synthesized precursor peptides that are converted into tricyclic depsipeptides through the action of ATP GRASP-like ligases and an unidentified peptidase cleaving the modified precursor peptide (Philmus et al., 2009, Ziemert et al., 2008b). The generated N-terminus of the core peptide is blocked by an acetylation catalyzed by a dedicated acetyltransferase. Cyanobactins (e.g. prenylagaramides, aerucyclamides) are another class of RiPPs that are assembled through the post-translational proteolytic cleavage and head-to-tail macrocyclization of short precursor proteins. Some of the cyanobactin amino acids undergo modifications, such as heterocyclization, oxidation, prenylation, and epimerization. Genome sequencing efforts have shown that, when compared with NRPS, particular RiPPs are taxonomically more widely distributed (e.g. Philmus et al., 2008).

Fig. 4.

Overview of gene clusters encoding either nonribosomal peptide synthesis (NRPS), hybrid polyketide synthesis (PKS)-NRPS, or ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides (RiPPs) in Planktothrix agardhii and P. rubescens.

5.2. Regulation of toxin and bioactive peptide synthesis

In Planktothrix, the entire gene cluster encoding MC biosynthesis (mcy) comprises ten genes (approx. 55 kb), consisting of PKS, NRPS and tailoring enzymes (Fig. 4). McyD, McyE, McyG constitute PKS or hybdrid NRPS-PKS and are responsible for the production of the amino acid Adda and the activation and condensation of D-glutamate. McyA, McyB, McyC are NRPS and responsible for the incorporation of the other five amino acids in positions 7, 1, 2, 3, 4 of the MC molecule (Tillett et al., 2000). Tailoring enzymes comprise an ABC transport protein (McyH), a type II thioesterase (McyT), and an O-methyltransferase (McyJ). The involvement of tailoring mcy genes into MC synthesis has been proven by genetic manipulation (Christiansen et al., 2003, Christiansen et al., 2008a). Comparing the mcy gene cluster with other cyanobacteria revealed that the mcyT gene is exclusively found in Planktothrix. Type II thioesterases (TeII) have been shown to positively influence the synthesis rate of corresponding NRPS (Schwarzer et al., 2002). Accordingly, the experimental inactivation of the mcyT gene led to a significant decrease in MC synthesis (Christiansen et al., 2008a).

In analogy to Microcystis (Kaebernick et al., 2000), for the mcy gene cluster, a bi-directional promoter has been described, which, however, does not show similarity at the nucleic acid level to Microcystis and is located between mcyT (the type II thioesterase) and mcyD (a type I PKS); (Christiansen et al., 2003). This bi-directional promoter regulates two opposite arranged genes that are part of the multidomain enzyme system. In silico analysis of the bi-directional promoter region led to the identification of binding boxes of the ubiquitous nitrogen transcription factor (NtcA) and ferric uptake regulator (Fur). NtcA is an up-regulator and senses the intracellular N status and positively regulates genes by binding to their promoter regions at sites that contain the consensus sequence. In contrast, Fur acts as repressor, and when complexed to ferrous ions, a dimer of Fur binds to a specific DNA sequence (known as Fur-box) located in iron-responsive gene promoters (Martin-Luna et al., 2006). Virtually all experiments on transcription factors have been performed with Microcystis and while N-NO3 availability left mcyD transcription and MC synthesis unaltered (Sevilla et al., 2010), the iron availability influenced mcyD expression and MC synthesis (Sevilla et al., 2008). For Planktothrix, physiologically induced changes in the mcy gene transcription rate by higher irradiance were shown to correlate with the net production rate of MC (Tonk et al., 2005). Overall, similar to Microcystis, no induction by nutrients (nitrogen, iron) of mcy gene expression was observed, rather mcy gene expression was found modulated in response to environmental conditions. Consequently, the hypothesis that MC synthesis production is mostly related to cell division and growth, but various environmental parameters affect MC synthesis indirectly through cellular growth is still relevant (Orr and Jones, 1998, Briand et al., 2005).

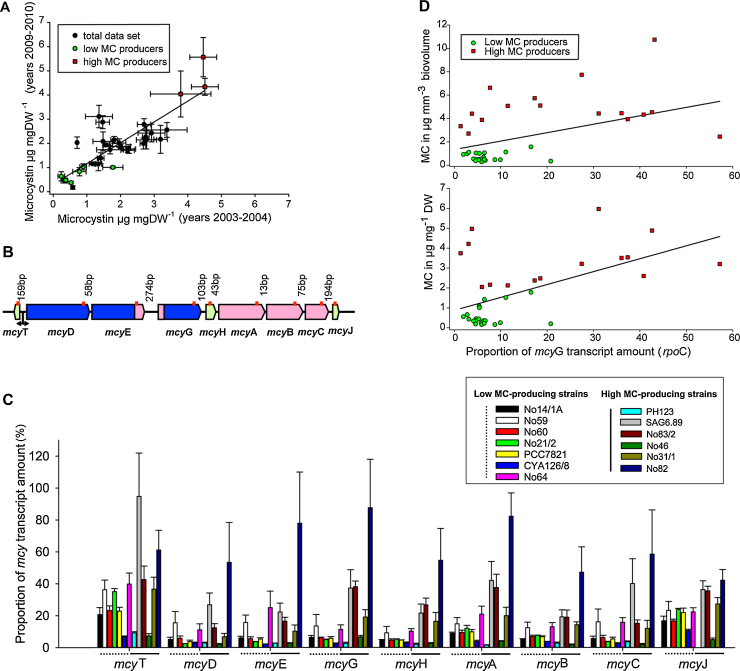

Conversely, even for those strains containing the full mcy gene cluster, the analysis of MC-producing strains showed substantial differences in MC content independent of culture age under identical environmental conditions (Fig. 5A). In P. agardhii and P. rubescens the MC contents have been found to vary 10-fold (n = 17, 0.28–2.9 μg MC mg−1 dry weight), (Welker et al., 2004), and 16-fold (n = 17, 0.3–4.9 μg MC mg−1 dry weight) between strains (Kurmayer et al., 2005). A strain-specific pattern also has been found for the cellular anabaenopeptin contents (Kosol et al., 2009). In order to identify potential causes, thirteen strains were grown semi-continuously under maximum growth rate conditions at 20 °C under high irradiance (50 μmol m−2 s−1) and extracted for both MC and for mRNA to quantify the transcript amount of each of the nine mcy genes in relation to DNA dependent RNA polymerase (rpoC), (Fig. 5B), (Supplemental Information). While for the whole mcy gene cluster there was considerable variation in the transcript amount within individual mcy genes (Fig. 5C), there was a significant difference in the mcyG transcript amount between low and high MC producers (Mann–Whitney U test, n = 36, p = 0.002), (Table 2). Linear regression analysis revealed a significant dependence of the MC content on the mcyG transcript amount (p < 0.01, Fig. 5D). Since the intergenic spacer region located at the 5′-end of mcyG extends 270 bp and contains a high frequency of mutations (Chen et al., 2016) it seems possible that the mcyG transcript amount is of relevance for the translation of the multi-domain enzyme system regulating MC synthesis.

Fig. 5.

(A) Relationship between MC content (μg MC-LR equiv. mg dry weight (DW)−1) as determined from strains of Planktothrix agardhii and P. rubescens in the course of two consecutive experiments performed during 2003–2004 (Kosol et al., 2009) and 2009–2010 (R.K. unpublished data). (B) Schematic view of the mcy gene cluster consisting of nine genes encoding MC synthesis and nucleotide sequence variation within the intergenic spacer region as observed from 13 strains (see Table 2). The red lines indicate the loci used for quantification of the transcript amount by qPCR. (C) Average ± SE transcript amounts of mcy genes determined for low MC-producing and high MC-producing strains using rpoC as a reference (see Table 2). (D) Relationship between mcyG transcript amount and MC content per dry weight or per biovolume from strains (Table 2).

Table 2.

Strains of Planktothrix agardhii and P. rubescens used for the quantification of mcy gene transcript amounts and the total microcystin (MC) content (see also Fig. 5A–D).

| Strain | Mutationa | n | μg MC mg DW−1 | μg MC mm−3 biovolume | %mcyG (rpoC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low MC-producing strains | |||||

| No14/1A | – | 3 | 0.38 ± 0.1 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 6.4 ± 2.1 |

| No59 | – | 2 | 0.46 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 13.5 ± 10.3 |

| No60 | – | 3 | 0.47 ± 0.1 | 0.27 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.4 |

| No21/2 | A | 2 | 0.77 ± 0.4 | 0.77 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.5 |

| PCC7821 | – | 2 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.5 |

| CYA126/8 | – | 3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.55 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.6 |

| No64 | A | 3 | 1.25 ± 0.3 | 1.57 ± 0.2 | 11.4 ± 5.3 |

| High MC-producing strains | |||||

| PH123 | – | 3 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 1.3 |

| SAG6.89 | B2 | 3 | 4 ± 2.1 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 37 ± 24 |

| No83/2 | B3 | 3 | 4.43 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 38 ± 6 |

| No46 | B4 | 2 | 5.26 ± 2 | 2.11 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 1.2 |

| No31/1 | B2 | 3 | 5.98 ± 1.5 | 2.61 ± 0.6 | 19.2 ± 8 |

| No82 | B3 | 3 | 6.01 ± 3.2 | 3.5 | 88 ± 61 |

Mutations: A, insertion of a putative Holiday-junction resolvase between mcyT and mcyD (1294 bp), Chen et al. (2016); B, occurrence of a 144 bp-deletion (B2) or a 17 bp-insertion (B3) or a 4 bp-insertion (B4).

Typically, within individual strains, numerous structurally related peptides have been found to be co-produced with MCs, and it has been shown that strains without MC production obligatory contain other structurally related peptides instead (e.g. Fujii et al., 2000). Strains have been shown to contain 1–7 different peptide structural families (Rohrlack et al., 2008, Kurmayer et al., 2015). There is evidence that the phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) act in trans in Bacillus subtilis and the same PPtase may convert the peptidyl carrier proteins (PCPs) of different NRPS to the active form (Mootz et al., 2001). In addition, different NRPS may depend on the same precursors, e.g. rare d/l-amino acids. For example, the peptides produced by strain CYA126/8, anabaenopeptins m/z 908, 915 and cyanopeptolins m/z 881, 961, all are known to contain the rare non proteinogenic amino acid homotyrosine (Okumura et al., 2009). Indeed after the insertional inactivation of the anabaenopeptilide (cyanopeptolin) synthetase of the MC-producing strain Anabaena 90, an increased synthesis of anabaenopeptin was observed in the mutant strain when compared with the wild type (Repka et al., 2004). In general, the knowledge on the regulation of NRPS and RiPPs in Planktothrix is scarce, although some results suggest that the co-production of peptides, such as anabaenopeptin and microviridin, mostly depends on cellular growth irrespective of whether cultures were light, N-, or P-limited (Rohrlack and Utkilen, 2007).

5.3. Evolution and distribution of toxin synthesis genes

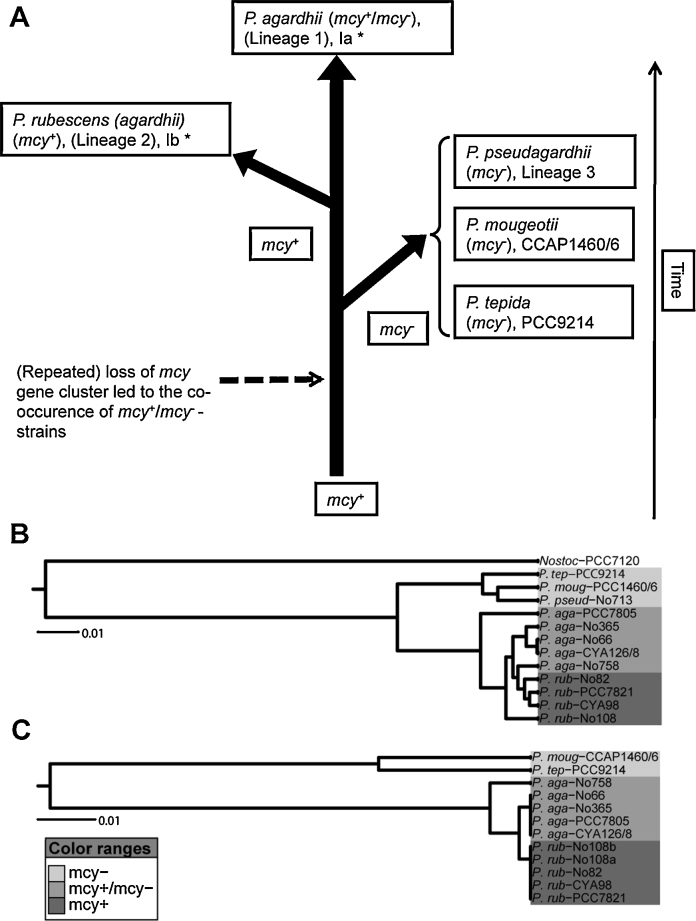

The elucidation of NRPS and RiPPs pathways also paved the way to analyze the distribution and evolution of these toxin synthesis genes within Planktothrix. In general, the activity of multiple enzymes in concert has been considered as a gene collective subjected to both horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and vertical transfer (Fischbach et al., 2008). For the phylum of cyanobacteria it has been shown that mcy and saxitoxin genes are phylogenetically old and probably all modern cyanobacteria share a common ancient ancestor of MC and possibly also saxitoxin synthesis (Fewer et al., 2007, Murray et al., 2011). A recent phylum-wide comparison of more than 120 genomes of different cyanobacteria genera revealed that secondary metabolite synthesis gene clusters are patchily distributed and about one quarter of these gene clusters showed signs of HGT events (Calteau et al., 2014), i.e. were flanked by genes encoding mobile elements (transposases). The majority of these gene cluster families, however, also showed signs of recombination, gene duplication, and gene loss with vertical inheritance. For the mcy gene cluster in Planktothrix, it could be shown that nontoxic strains have lost more than 90% of it (Christiansen et al., 2008a). It could be estimated from the mcy gene cluster remnants that the event of losing the mcy gene cluster happened repeatedly several millions of years ago. In a subsequent study (Kurmayer et al., 2015), several phylogenetic lineages [1 (1A, 1B), 2 (2A), 3] were identified using multi locus sequence analysis (MLSA) and mcy gene cluster remnants were identified in nontoxic strains assigned to different species: P. agardhii (lineage 1, 1A) and P. pseudagardhii (lineage 3). Furthermore, the P. agardhii lineage 1 contained a number of strains that either lost or retained the mcy gene cluster, suggesting that the loss of toxicity per se did not lead to phylogenetic diversification. Consequently, on a global scale, neither toxic nor nontoxic genotypes were strongly favored by natural selection and have, therefore, co-existed for evolutionary periods. Thus, the ecological diversification of either a genotype that lost or a genotype that retained the mcy gene cluster can explain the contrasting proportion of mcy genes in populations growing in individual habitats (e.g. Kurmayer et al., 2011). This mcy gene loss hypothesis was confirmed, as other species such as P. mougeotii (Suda et al., 2002) and P. tepida (Gaget et al., 2015) were also found to carry several hundred base pairs of the mcy gene cluster 5′-end flanking region (Suppl. Table 1). When comparing the phylogenetic tree obtained from MLSA, a phylogenetic congruence was obtained when a phylogenetic tree was calculated independently using these mcy gene cluster flanking regions (254 bp, Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

(A) Scheme on inheritance of the mcy gene cluster in Planktothrix spp. according to Kurmayer et al. (2015) and unpublished data (R.K.). *Ia, Ib denote lineages according to Gaget et al. (2015). (B) Phylogenetic tree showing relatedness of Planktothrix species according to MLSA (Kurmayer et al., 2015). (C) Phylogenetic tree showing relatedness of Planktothrix species according to mcy gene cluster 5′-end flanking regions (254 bp), (R.K. unpublished).

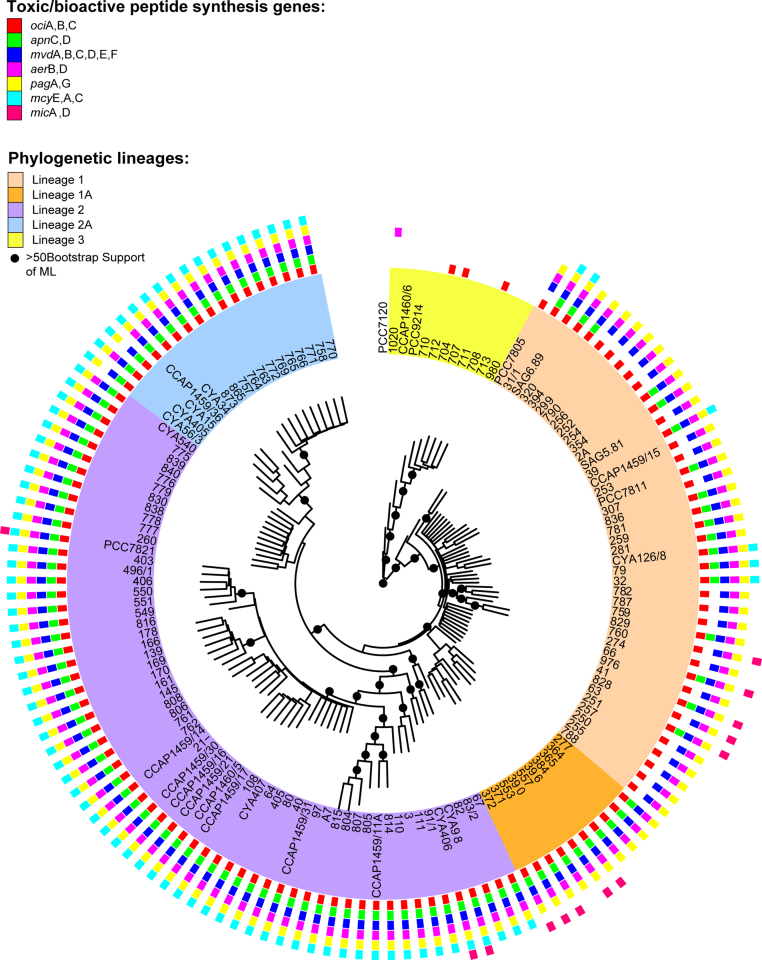

Using the same Planktothrix strains, the presence or absence of additional peptide synthesis (Fig. 4) was tested using several more conserved gene regions (Supplementary Table 2): Strains assigned to P. agardhii and P. rubescens lineages 1 + 2 (Kurmayer et al., 2015) typically contained peptide synthesis gene loci indicative of aeruginoside, anabaenopeptin, cyanopeptolin, and microviridin synthesis pathways (R.K., E.E., unpublished data). In contrast, the putative microginin synthesis gene loci occurred more patchily (Fig. 7). In contrast, the same gene loci could not be detected within the strains assigned to lineage 3 comprising the P. pseudagardhii, P. mougeotii, and P. tepida species. The only exception was the partial ociB gene of the cyanopeptolin synthesis gene cluster putatively encoding the activation of the nonribosomal amino acid Ahp in the course of cyanopeptolin synthesis (Rouhiainen et al., 2000). At present, the information on peptide metabolites within Planktothrix strains assigned to species other than P. agardhii and P. rubescens is limited. Any structural variants of known bioactive peptides (Fig. 3) from the strains of P. pseudagardhii were found (Kurmayer et al., 2015). It has been reported that, for strains assigned to P. tepida, P. serta, and P. paucivesiculata, no evidence for any peptide metabolites has been obtained or only small peaks have been detected that were unrelated to known cyanobacterial peptides (Gaget et al., 2015). From these results, it is tempting to speculate that the production of the above described toxins and bioactive peptides (Fig. 3) is linked to the evolution of the P. agardhii and P. rubescens complex because either NRPS gene clusters (mcy genes) were lost in ancestral genotypes previously, before species diversification (P. agardhii and P. rubescens vs P. pseudagardhii, P. mougeotii, P. tepida), or the known bioactive peptide synthesis gene clusters (NRPS and RiPPs) evolved lately within the P. agardhii and P. rubescens complex.

Fig. 7.

Distribution of gene loci indicative of peptide synthesis gene clusters within Planktothrix phylogenetic lineages (Kurmayer et al., 2015) (R.K., E.E., unpublished data, Supplementary Table 2).

5.4. Gene distribution in field populations and population genetic structure

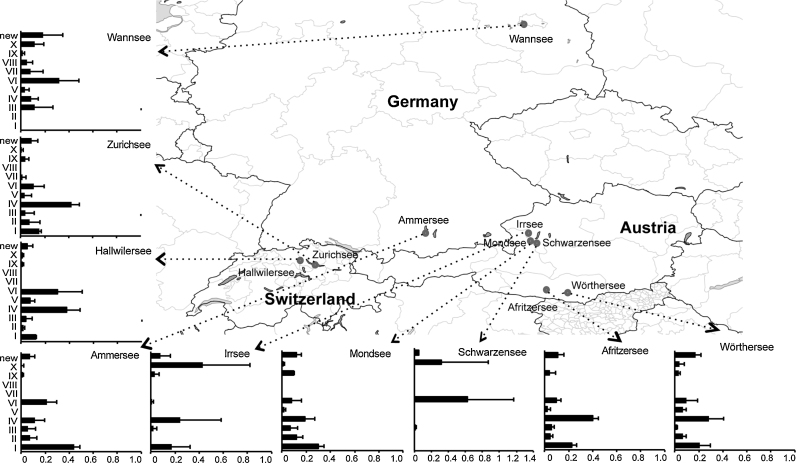

Due to the age of the mcy gene loss event, it was further hypothesized that Planktothrix meanwhile could have adapted to a variety of ecological factors not causally related to MC synthesis (Christiansen et al., 2008a). For example, the strains of toxic lineage 2 (Kurmayer et al., 2015) (Fig. 6) contained many red-pigmented strains assigned to P. rubescens, which have resistance to high hydrostatic pressure under deep-mixing conditions due to adaptation in gas vesicle protein size when compared with green-pigmented P. agardhii strains of lineage 1 (Beard et al., 2000). This hypothesis was tested using phytoplankton samples, which were preserved on glass fiber filters from the deep mesotrophic Lake Zürich (Switzerland) for 29 years from 1980 to 2009 in order to monitor the re-oligotrophication process (Ostermaier et al., 2012). By means of the lineage specific qPCR probes, it could be shown that the green-pigmented nontoxic lineage 1 occurred regularly but never became abundant, while the red-pigmented lineage 2 that retained the mcy gene cluster gained in proportion with the total population increase (Ostermaier et al., 2012). It was concluded that physical factors, such as deep-mixing events in the water column, competitively excluded genotypes from lineage 1 (containing the nontoxic genotypes) and indirectly contributed to the stability of the genotype composition in this ecosystem. This result helps to explain why the composition of the toxic or nontoxic genotypes varies spatially on a geographical scale and red- vs. green-pigmented populations differ consistently in mcy genotype proportion over years (Kurmayer et al., 2011). Consequently, green-pigmented Planktothrix populations typically have a lower proportion of mcy genotypes when compared with red-pigmented Planktothrix populations because many of the green-pigmented genotypes lost the mcy gene cluster (see section 5.3). Within red-pigmented populations, the mcyBA1 (adenylation-domain) genotype composition was found to vary consistently between spatially isolated populations for several years (Fig. 8), suggesting that once a population genotype structure is established in a specific lake habitat, changes in the population's genetic structure are unlikely to occur seasonally. Rohrlack et al. (2008) reported that the same chemotypes (as identified by toxins or bioactive peptide markers) have been isolated repeatedly over a period of 30 years from specific deep mesotrophic lakes in Norway. These data support the overall conclusion that the evolution of toxicity in P. agardhii and P. rubescens populations is slow.

Fig. 8.

Population genetic structure as revealed by mcyBA1 restriction type profiling showing the existence of homogeneous and more heterogeneous populations in geographically close but spatially isolated lakes during several years (Kurmayer and Gumpenberger, 2006).

In environmental microbiology, some effort has been devoted to finding out how much genotypic and possibly phenotypic variation should be considered as selectively neutral (e.g. Thompson et al., 2005). There is evidence that considers much of genetic variation neutral by taking into account the simplistic models of patch colonization in metapopulations (Fraser et al., 2009). Toxigenic cyanobacteria are not an exception and although the potential to generate structural toxic or bioactive peptide diversity is considered advantageous (see section 6), a large part of the genotypic variation partly resulting in phenotypic variation has been found selectively neutral (Kurmayer and Gumpenberger, 2006, Niedermeyer et al., 2014). Thus, the founder effects and random drift need to be invoked regarding why particular genotypes dominate in one habitat but not in another (e.g. De Meester et al., 2002, Van Gremberghe et al., 2009). Such random drift can lead to the appearance of unique and novel MC structural variants in populations of one specific habitat as caused by single point mutations within responsible enzyme domains (Christiansen et al., 2008b). The consequences of random drift for the occurrence of cyanotoxins and bioactive peptides, however, are poorly explored, as scientific studies involve a limited sample size with strain or field samples originating from a specific habitat or region. The mapping of toxin and bioactive peptide diversity within phylogenetic lineages against geographic distance was started only recently, and although many bioactive peptides were found cosmopolitan, the probability that strains differ in peptide composition also increased with the geographic distance (Kurmayer et al., 2015). More prominent examples of biogeographic patterns of toxin production have been reported for the hepatotoxic cylindrospermopsin from Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (e.g. Neilan et al., 2003) or for the neurotoxic saxitoxin from Anabaena circinalis (Beltran and Neilan, 2000). For Planktothrix, it cannot yet be ruled out that phylogenetically indistinguishable strains may produce different toxic compounds in different geographic locations.

6. Toxins and bioactive peptides and niche construction

With increasing evidence that ecological and evolutionary time scales can be congruent (e.g. Ellner, 2013), environmental modifications such as induced by bloom-forming Planktothrix might be recognized as an important selective agent. However, relatively few studies have explored the idea that bloom-forming cyanobacteria act as ecosystem engineers, for example by altering the physico-chemical environment of the water column (Breitburg et al., 2010). Following Matthews et al. (2014), three criteria should be fulfilled so that an organism can be considered as a niche constructor: (i) environmental conditions must be significantly modified, (ii) the environmental modifications also must influence the selection pressure on a recipient of niche construction, and (iii) an evolutionary response in a recipient of niche construction that is caused by the environmental modification of the niche constructor must be detectable. It is tempting to speculate that by building up populations with high density sometimes lasting for years (e.g. Rücker et al., 1997), (Section 3), P. agardhii and P. rubescens act as a niche constructor either in shallow turbid lakes through the formation of one of the two alternative stable states (Scheffer et al., 1997) or in deep mesotrophic lakes by forming metalimnetic layers during the physical stratification of the water column (Salcher et al., 2011). It is more difficult to conclude on the possible evolutionary response, for example due to intra- and extracellularly occurring bioactive secondary metabolites. In the light of the three categories listed by Matthews et al. (2014), the following can be stated: (i) Many of the toxic and bioactive peptides are produced in large amounts (i.e. comparable to the amounts of chlorophyll, 0.1–1% of dry weight). Thus, individual bioactive peptides will affect other aquatic biota qualitatively (due to a potential bioactivity) and quantitatively through providing nutrition, e.g. serving as a substratum for associated heterotrophic microorganisms. Notably, specific enzymes involved in MC degradation by heterotrophic bacteria have been described already two decades ago (Bourne et al., 1996). While these MC-degrading enzymes have been found widely distributed, the specificity of the described MC degradation pathways toward MC structural variants degradation is still under discussion (Dziga et al., 2013). (ii) Since bioactivity has been shown for individual structural variants of one specific peptide family (see Section 5.1) it is reasonable to conclude that in P. agardhii and P. rubescens secondary metabolite synthesis serves in part as a chemical defense against various antagonists. From an evolutionary point of view, it is the metabolic capability to generate structural diversity of secondary metabolites that is considered of evolutionary advantage (Firn and Jones, 2000). The function of chemical defense does not necessarily preclude other intracellular (physiological) roles (e.g. Neilan et al., 2013), but taking the structural variability and bioactivity of the various peptide families (Section 5.1) into account, the mediation of chemical interactions is considered the most parsimonious ultimate factor driving the evolution of bioactive secondary metabolism in Planktothrix. (iii) Examples of adaptive processes possibly driven by toxins and bioactive peptides exist, highlighting the niche construction hypothesis. In general, the macroscopic filaments have a lower risk of being grazed by crustaceans and other herbivorous animals, nevertheless, within zooplankton, different evolutionary strategies to co-exist with MC-producing P. rubescens have been observed (Kurmayer and Jüttner, 1999). Blom et al. (2006) investigated the adaptation of crustaceans to oscillapeptin J and MC. The adaptation process that occurred in Daphnia was explained by the intense contact with the two different peptides as a result of filter-feeding. Accordingly, amoeba have been described to feed on P. rubecens filaments with an indication that ectosymbiontic bacteria (related to Paucibacter toxinivorans, Rapala et al., 2005) contributed to MC degradation (Dirren et al., 2014). More recently, it has been argued that besides chemical deterrence from crustaceans, bioactive peptides mediate chemical defense against fungal parasites such as chytridiomycetes. Sonstebo and Rohrlack (2011) reported weak, albeit significant, relationships between the severity of the infection of a certain P. agardhii and P. rubescens strain by the chytrid isolate and the occurrence of peptides in the same cell culture (cyanopeptolin, anabaenopeptins, MC, microviridin, and aeruginosin). Since these parasites grow with rhizoids by penetrating the host cell wall and releasing proteases to facilitate the digestion of cellular components, which are thereafter adsorbed (Krarup et al., 1994), it is possible that the growth of the fungal parasites is directly influenced by the high intracellular toxin and bioactive peptide concentrations. Indeed experimental inactivation of peptide synthesis by genetic manipulation led to increased sensitivity to parasitic infection for P. agardhii mutants lacking either MC, anabaenopeptin, or microviridin (Rohrlack et al., 2013). Interestingly, different Planktothrix strains also vary in the susceptibility to infection by a certain chytrid isolate (Sonstebo and Rohrlack, 2011) thereby suggesting that chytrid genotypes possibly have become adapted to the bioactive peptides synthesized by Planktothrix through co-evolutionary adaptation. Although this evolutionary interaction is still hypothetical, it can serve as an example how toxins and bioactive peptide production by Planktothrix can lead to niche construction in pelagic ecosystems. Most recently, in Lake Kolbotnvannet (Norway), the population density development has been observed for a specific Planktothrix host genotype and its putative chytrid parasite for a period of 30 years from the sediment extracted DNA (Kyle et al., 2015). Contrary to the expectations from eukaryotic algae using Asterionella formosa and a chytrid parasite as a model (e.g. De Bruin et al., 2008), no classical host-parasite cycling was observed. The lack of a visible host-parasite cycling might be explained by the oligopeptide production of Planktothrix slowing down the co-evolutionary cycle. From an ecological point of view, the metalimnetic life form of red-pigmented Planktothrix might also be invoked to explain why red-pigmented Planktothrix typically has a 100% proportion of mcy genotypes while the proportion of mcy genotypes in green-pigmented populations is much lower (Kurmayer et al., 2011). Since red-pigmented populations typically grow under more oligotrophic conditions when compared with green-pigmented life form occurring in shallow, nutrient-rich waters the chemical defense in general might be a stronger selective factor. Individual peptide production has been genetically inactivated repeatedly in P. agardhii and P. rubescens strains (Kurmayer and Christiansen, 2009), and controlled experiments using various combinations of individual peptide knock out mutants would contribute to clarify the role of individual peptides during a putative Planktothrix host-chytrid co-evolutionary process.

It is generally accepted that chemical interactions occur widely within macroscopic algae or cyanobacteria and various associated biota (phages, heterotrophic bacteria, eukaryotic algae, and protozoans), (e.g. Gerphagnon et al., 2015), while the role of individual bioactive peptides (Section 5.1) is less explored. Sedmak et al. (2008) have proposed that individual structural variants of cyanopeptolins (planktopeptin) and anabaenopeptins isolated from P. rubescens can provoke lysis of Microcystis aeruginosa via the induction of virus-like particles when applied in the nano-micromolar concentration range. While experiments using the direct counting of viral particles and traditional plaque assays would allow to prove this putative peptide-driven induction of lysogeny (Sedmak et al., 2009), this chemical interaction potentially contributes to Planktothrix niche construction. In general, viral infection has been implicated as an important factor that triggers a population decline either in limiting the overall extent of the population development or in influencing the composition of the community and population diversity through host-specific mortality. Very few studies have reported on the phages associated with Planktothrix (Deng and Hayes, 2008, Gao et al., 2009). The morphology of Planktothrix phages includes all three common tailed bacteriophages in the order of Caudovirales: Myoviridae (icosahedral heads and contractile tails), Siphoviridae (icosahedral heads with long, noncontractile flexous tails), and Podoviridae (icosahedral heads with either no or very short tails). In addition, a rare filamentous morphotype of Planktothrix phage has been reported (Deng and Hayes, 2008). Phylogenetic analysis of the major capsid proteins of a Planktothrix phage isolated in China revealed an independent branch that is quite different from other known tailed cyanophages and phages (Gao et al., 2012). Thus, it was suggested that they are probably diverse, and divergent from marine cyanophages. In another study, eleven of the twelve Planktothrix phages isolated in the UK failed to yield gene amplification products, either when using primer pairs known to amplify gene fragments from diverse marine and freshwater cyanophages (Short and Suttle, 2005) or when using primers designed to amplify a gene fragment encoding the major capsid protein from freshwater cyanophages (Baker et al., 2006). Considering the genetic diversity of the phages reported so far as well as the strain-specific influence of bioactive peptides in the induction of lysogeny (Sedmak et al., 2008), it is tempting to speculate that the observed peptide diversity also mediates strain-specific interactions through co-evolutionary processes.

7. Harmful algal bloom management

Population genetic studies have shown that the field populations of P. rubescens always contain MCs – typically in high cellular contents (e.g. Fastner et al., 1999), and the risks of human exposure to MCs thus increases if P. rubescens forms surface blooms or scums. Numerous studies have investigated whether Planktothrix biovolume and/or toxin synthesis gene abundance can be used as a predicting variable for the concentrations of toxins such as MCs. A number of the studies indeed showed a significant relationship between P. agardhii and P. rubescens biovolume and MC concentration (Table 3). Furthermore, the quantification of mcy genes of P. rubescens also showed a high quantitative ability to predict MC concentrations (Ostermaier and Kurmayer, 2010). These results point toward a high stability of population genetic structure in a temporal dimension while between habitats more pronounced variation in average MC content of red-pigmented and green-pigmented Planktothrix populations is observed (Salmaso et al., 2014). The local differences in population average MC content can be explained both by local selective factors (e.g. physical forcing), and also neutral selection and random effects on population genetic structure (see section 5.4). In a few studies, the measurement of toxin synthesis genotype abundance was not found to be a satisfactory method for use in monitoring programs in order to predict MC net production from green-pigmented Planktothrix populations (e.g. Briand et al., 2008). Particularly for MCs, these contrasting results may be caused by: (1) several cyanobacteria producing MCs frequently co-exist in water bodies and not all MC producers may have been identified, (2) the semi-logarithmic calibration curves used for qPCR based quantification cause limitations with regard to the accuracy in estimating mcy genotype numbers (Schober et al., 2007), (3) mutants that contain the respective genes but have been inactivated in MC production (Christiansen et al., 2006) may actually decrease MC concentrations resulting in a higher variability of the outcome of MC concentrations as a factor of biovolume and/or mcy gene abundance. The influence of mutations resulting in MC synthesis inactivation on the average MC content of a Planktothrix population has been the least explored. A spatial-temporal variability of MC synthesis-inactivating mutations has been observed (5–26%, Chen et al., 2016). In order to overcome this uncertainty, the use of quantile regressions has been proposed allowing to estimate the worst case scenario of MC concentrations in a certain ecosystem (e.g. Salmaso et al., 2014).

Table 3.

Significant linear relationships reported from the literature between Planktothrix cell numbers (biovolume) and microcystin (MC) concentration, mcy genotype and MC concentration, mcy genotype vs. Planktothrix cell numbers (biovolume).

| Planktothrix sp. population | Habitat | Linear regression curve | Range (μg L−1) | P | R2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biovolume vs. MC concentration | ||||||

| Red-pigmented | L. Occhito (IT) | MC (μg L−1) = 0.54 + 3.16 ± 0.25 biovolume mm3 L−1 | 0–17 | <0.001 | nd | Salmaso et al., 2014 |

| Red-pigmented | L. Pusiano (IT) | MC (μg L−1) = −0.18 + 0.69 ± 0.08 biovolume mm3 L−1 | 0.1–4.9 | <0.001 | nd | Salmaso et al., 2014 |

| Red-pigmented | L. Ledro (IT) | MC (μg L−1) = −0.02 + 0.51 ± 0.04 biovolume mm3 L−1 | 0–4.5 | <0.001 | nd | Salmaso et al., 2014 |

| Red-pigmented | L. Garda (IT) | MC (μg L−1) = −0.02 + 0.78 ± 0.08 biovolume mm3 L−1 | 0–0.55 | <0.001 | nd | Salmaso et al., 2014 |

| Green-pigmented | L. Lubosinskie (PL) | MC (μg L−1) = 10.251 + 0.3604 biovolume mm3 L−1 | 4–74 | – | 0.64 | Kokocinski et al., 2011 |

| Green-pigmented | 102 lakes in Brandenburg (DE) | MC (μg L−1) = 0.65 + 1.575 biovolume mm3 L−1 | 0–64 | – | 0.89 | Dolman et al., 2012 |

| Green-pigmented | Lake in Paris (FR) | MC (μg L−1) = 0.512 + 0.034 biovolume mm3 L−1 | 0.1–7.4 | <0.001 | 0.49 | Catherine et al., 2008 |

| Red-pigmented | Lac du Bourget (FR) | MC (μg L−1) = 8500 cells ml−1 | 1–6.7 | – | 0.72 | Briand et al., 2005 |

| mcy genotype vs. MC concentration | ||||||

| Red-pigmented (P. rubescens) | Twelve lakes in the Alps (A, CH, DE) | log10 MC (μg L−1) = 0.98 + 0.8 log10mcyA gene (biovolume mm3 L−1) | 0–6.2 | <0.001 | 0.73 | Ostermaier and Kurmayer, 2010 |

| Planktothrix sp. | Hauninen Reservoir, Raisio (FI) | MC (μg L−1) = 0.0083 + 10−5mcyE gene copies ml−1 | 0–0.24 | <0.001 | 0.84 | Hautala et al., 2013 |

| mcy genotype vs. cells (biovolume) | ||||||

| Planktothrix spp. | 24 lakes in Europe | log10mcyB (mm3 L−1) = −0.441 + 1.010 PC gene log10 biovolume mm3 L−1 | nd | – | 0.78 | Kurmayer et al., 2011 |

| Red-pigmented (P. rubescens) | L. Gerosa (IT) | 106mcyB cells L−1 = −1.74 + 0.97 × 106 cells L−1 | 0–1.03 | <0.001 | 0.98 | Manganelli et al., 2010 |

nd, not determined; PC, phycocyanin.

The blooming of Planktothrix regularly leads to toxic outbreaks, e.g. in December 2013 the water distributed in Užice in Serbia was cancelled for drinking and food preparation because of the intense blooming of toxic P. rubescens in Lake Vrutci, which served as the water supply. There is a history of these relatively sudden mass appearances of toxic P. rubescens in lakes and reservoirs (e.g. Almodovar et al., 2004, Paulino et al., 2009, Naselli-Flores et al., 2007, Salmaso and Padisak, 2007). The often cited (sudden) appearance and disappearance in ecosystems (see examples above) probably needs attention during the surveillance of water bodies, for example in the course of frameworks like the water safety plan (e.g. Chorus, 2005). Typically, during traditional sample processing, approximately 400 units of phytoplankton specimen are counted, which is a number considered to be insufficient to monitor rare species occurring with low percentage. Therefore, Planktothrix occurring subdominantly (e.g. <10%, Bonilla et al., 2012) is overlooked and the possible environmental conditions triggering the sudden increase are not monitored. Compared with microscopy, the application of automated monitoring platforms equipped with a scanning flow cytometer and a multiparameter probe are probably the most efficient in monitoring the build-up of metalimnetic and epilimnetic bloom layers (e.g. Pomati et al., 2011). Mobile autonomous sampling platforms (e.g. Garneau et al., 2013) provide additional information on the spatial-temporal variability of P. agardhii and P. rubescens biovolume distribution. Since these real-time observation tools have been increasingly applied during the last decade, it is expected that environmental factors contributing to the ecological success of P. agardhii and P. rubescens will be better documented. It is known that thermally stratified and eutrophic reservoirs favor metalimnetic stratifying cyanobacteria such as Planktothrix (Naselli-Flores, 2003). Sometimes, new dam reservoirs become colonized by Planktothrix sp. (Pawlik-Skowronska and Toporowska, 2011). According to Padisák et al. (2015), today more than 50,000 reservoirs with dams >15 m exist. They were constructed in arid regions, in particular, and might serve as stepping stones facilitating the dispersal of phytoplankton. If man-made reservoirs can become one of the key habitats of this genus, understanding the invasion potential of Planktothrix sp. is of relevance, not least due to the ongoing construction of hydropower dams worldwide (Zarfl et al., 2015). In summary, the data available warrant research directed toward Planktothrix epidemics in certain habitats and should take into account the invasive potential of certain taxa depending on the environmental setting, including toxin and bioactive peptide production. As soon as Planktothrix sp. is established in a system, a possible research question is whether toxin and bioactive peptide production contributes to the resistance of the Planktothrix sp. total population toward bloom restoration efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the invitation to write this manuscript and to the comments of the two anonymous reviewers. The excellent assistance of Mark Frei, Katharina Moosbrugger, Maria Reischauer, and Anneliese Wiedlroither in the laboratory is gratefully acknowledged. Guntram Christiansen contributed to the experiments and the preparation of parts of this manuscript. We thank Benjamin Philmus for drawing peptide chemical structures. Many colleagues are acknowledged for providing strains material and/or water samples (Reyhan Akcalaan, Olga Babanazarova, Sandra Barnard, David Bird, Alessandra Giani, Frederico Marrone, Luigi Naselli-Flores, Sergio Paulino, and Linda Tonk). The research has been supported financially by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project grant numbers P24070, P20231 to R.K. We thank the European Cooperation in Science and Technology, COST Action ES 1105 “CYANOCOST – Cyanobacterial blooms and toxins in water resources: Occurrence, impacts, and management” for knowledge sharing and networking.[SS]

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.hal.2016.01.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Almodovar A., Nicola G.G., Nuevo M. Effects of a bloom of Planktothrix rubescens on the fish community of a Spanish reservoir. Limnetica. 2004;23(1–2):167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostidis K., Komárek J. Modern approach to the classification system of cyanophytes, 3-Oscillatoriales. Algol. Stud. 1988;50–53:327–472. [Google Scholar]

- Baker A.C., Goddard V.J., Davy J., Schroeder D.C., Adams D.G., Wilson W.H. Identification of a diagnostic marker to detect freshwater cyanophages of filamentous cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72(9):5713–5719. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00270-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P.D., Humpage A.R. Toxicity associated with commonly occurring cyanobacteria in surface waters of the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1994;45(5):773–786. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H.I., Keller S., Wolter F.E., Nicholson G.J., Jung G., Süssmuth R.D., Jüttner F. Planktocyclin, a cyclooctapeptide protease inhibitor produced by the freshwater cyanobacterium Planktothrix rubescens. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70(10):1611–1615. doi: 10.1021/np0700873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard S.J., Davis P.A., Iglesias-Rodriguez D., Skulberg O.M., Walsby A.E. Gas vesicle genes in Planktothrix spp. from Nordic lakes: strains with weak gas vesicles possess a longer variant of gvpC. Microbiology. 2000;146(8):2009–2018. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran E.C., Neilan B.A. Geographical segregation of the neurotoxin-producing cyanobacterium Anabaena circinalis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66(10):4468–4474. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4468-4474.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom J.F., Baumann H.I., Codd G.A., Jüttner F. Sensitivity and adaptation of aquatic organisms to oscillapeptin J and [d-Asp3,(E)-Dhb7]microcystin-RR. Arch. Hydrobiol. 2006;167(1–4):547–559. [Google Scholar]

- Blom J.F., Bister B., Bischoff D., Nicholson G., Jung G., Süssmuth R.D., Jüttner F. Oscillapeptin J, a new grazer toxin of the freshwater cyanobacterium Planktothrix rubescens. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66(3):431–434. doi: 10.1021/np020397f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla S., Aubriot L., Soares M.C.S., González-Piana M., Fabre A., Huszar V.L.M., Lürling M., Antoniades D., Padisák J., Kruk C. What drives the distribution of the bloom-forming cyanobacteria Planktothrix agardhii and Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012;79(3):594–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchamma E., Derraz M., Naji B., Dauta A. Influence of nutrient conditions on the growth and intracellular storage capacities (nitrogen and phosphorus) of Planktothrix agardhii isolated from eutrophic El Kansera impoundment waters (Morocco) Acta Bot. Gall. 2004;151(4):381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Breitburg D.L., Crump B.C., Dabiri J.O., Gallegos C.L. Ecosystem engineers in the pelagic realm: alteration of habitat by species ranging from microbes to jellyfish. Integ. Comp. Biol. 2010;50(2):188–200. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand E., Gugger M., Francois J.-C., Bernard C., Humbert J.-F., Quiblier C. Temporal variations in the dynamics of potentially microcystin-producing strains in a bloom-forming Planktothrix agardhii (Cyanobacterium) population. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74(12):3839–3848. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02343-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand J.-F., Jacquet S., Flinois C., Avois-Jacquet C., Maisonnette C., Leberre B., Humbert J.-F. Variations in the microcystin production of Planktothrix rubescens (Cyanobacteria) assessed from a four-year survey of Lac du Bourget (France) and from laboratory experiments. Microb. Ecol. 2005;50(3):418–428. doi: 10.1007/s00248-005-0186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne D.G., Jones G.J., Blakeley R.L., Jones A., Negri A.P., Riddles P. Enzymatic pathway for the bacterial degradation of the cyanobacterial cyclic peptide toxin microcystin LR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62(11):4086–4094. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4086-4094.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calteau A., Fewer D.P., Latifi A., Coursin T., Laurent T., Jokela J., Kerfeld C.A., Sivonen K., Piel J., Gugger M. Phylum-wide comparative genomics unravel the diversity of secondary metabolism in Cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:977. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catherine A., Quiblier C., Yepremian C., Got P., Groleau A., Vincon-Leite B., Bernard C., Troussellier M. Collapse of a Planktothrix agardhii perennial bloom and microcystin dynamics in response to reduced phosphate concentrations in a temperate lake. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008;65(1):61–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q., Christiansen, G., Deng, L., Kurmayer, R., 2016. Emergence of nontoxic mutants as revealed by single filament analysis in bloom-forming Planktothrix. BMC Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chorus I. Water Safety Plans. In: Huisman J., Matthijs H.P., Visser P., editors. Harmful Cyanobacteria. Springer; Netherlands: 2005. pp. 201–227. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen G., Fastner J., Erhard M., Börner T., Dittmann E. Microcystin biosynthesis in Planktothrix: genes, evolution, and manipulation. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185(2):564–572. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.2.564-572.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen G., Kurmayer R., Liu Q., Börner T. Transposons inactivate biosynthesis of the nonribosomal peptide microcystin in naturally occurring Planktothrix spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72(1):117–123. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.117-123.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]