Abstract

Difluoromethanesulfonyl hypervalent iodonium ylides 2 were developed as electrophilic difluoromethylthiolation reagents for a wide range of nucleophiles. Enamines, indoles, β-keto esters, silyl enol ethers and pyrroles were effectively reacted with 2 affording desired difluoromethylthio (SCF2H)-substituted compounds in good to high yields under copper catalysis. The reaction of allyl alcohols with 2 under the same conditions provided difluoromethylsulfinyl (S(O)CF2H) products in good yields. The difluoromethylthiolation of enamines is particularly effective with wide generality, thus the enamine method was nicely extended to the synthesis of a series of difluoromethythiolated cyclic and acyclic β-keto esters, 1,3-diketones, pyrazole and pyrimidine derivatives by a consecutive, two-step one-pot reaction using 2.

Keywords: difluoromethylthiolation, hypervalent iodonium ylide, carbene, sulfur, fluorine

1. Introduction

Fluorine (F) and sulfur (S) atoms have been individually recognized over the past couple of decades to be important structural elements with biological activities in drugs [1–10]. These facts, together with the recent successful observation on the market that the trifluoromethyl (CF3) group is frequently found in pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals [11–15], have led medicinal chemists to explore the use of the trifluoromethylthio (SCF3) group as a strategic functional component to assist in drug discovery [16–38]. In recent years, more than a dozen attractive synthetic methods for introduction of the SCF3 group into target compounds have been successively reported [16–38]. In this context, the difluoromethylthio group (SCF2H) has emerged as a next potential subject in this field. While SCF3 is entirely lipophilic, the SCF2H group has the potential to be a weak hydrogen-bonding donor, which results in a suitable hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance of SCF2H-substituted molecules [39–42]. Thus, incorporation of SCF2H into biologically active molecules should permit the efficient design of novel, viable drug candidates. There are several synthetic approaches available for SCF2H-substituted compounds [43–59], such as nucleophilic reaction of appropriate thiolates to difluoromethyl carbine [43–53] and electrophilic or radical difluoromethylation of thiolates [54–56]. These methods rely upon the construction of a bond between S and CF2H, and therefore have some limitations, although recently Goossen et al. provided a solution via copper-mediated difluoromethylation of organothiocyanates [57,58]. Impressively, Shen and co-workers [60] reported Sandmeyer-type direct diifluoromethylthiolation using an N-heterocyclic carbene difluoromethylthiolated silver complex to provide aryl SCF2H compounds. The method is an ideal approach for introducing SCF2H, but the substrate scope is limited to diazonium salts. The same group reported the first shelf-stable electrophilic difluoromethylthiolation reagent, N-difluoromethylthiophtalimide or the Shen reagent (figure 1a) [61].

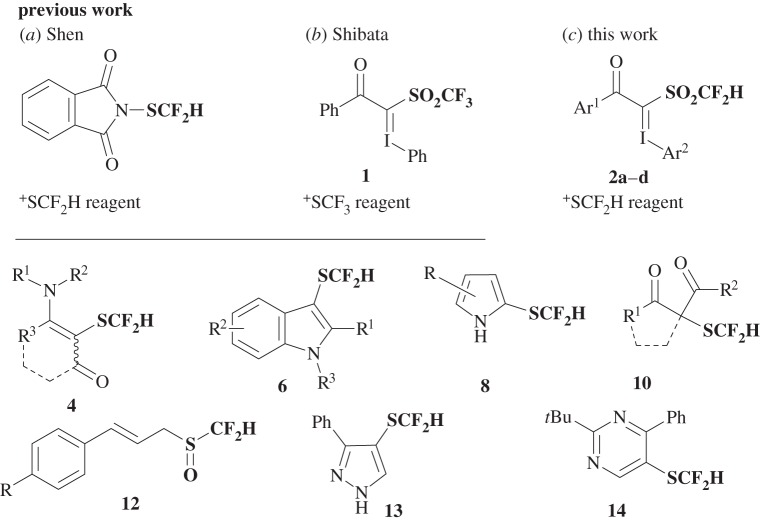

Figure 1.

Previous studies on (a) +SCF2H reagent, (b) +SCF3 reagent and (c) hypervalent iodonium ylides as +SCF2H reagents.

The Shen reagent is efficient, but new reagents and more methods to expand the accessibility to a wide variety of SCF2H compounds are continuously required. Incidentally, we reported in 2013 that trifluoromethanesulfonyl (SO2CF3) hypervalent iodonium ylide 1 is an efficient reagent for the electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolation reaction (figure 1b) [62]. Despite its carbon-SO2CF3 structure, a reactive SCF3 species is unexpectedly, but effectively released from 1 via C–S bond cleavage under copper catalysis allowing it to be transferred into a wide variety of nucleophilic substrates including enamines, indoles, β-keto esters, pyrroles [63], allylsilanes, silyl enol ethers [64], allyl alcohols and boronic acids [65]. Inspired by this powerful reactivity and wide substrate generality and linked to the mechanistic uniqueness of iodonium ylide reagent 1, we describe herein an investigation of novel shelf-stable electrophilic difluoromethylthiolation reagents 2 and their reactivity towards a variety of nucleophiles (figure 1c). Difluoromethanesulfonyl (SO2CF2H) hypervalent iodonium ylides 2 were found to be useful for electrophilic difluoromethylthiolation of a variety of nucleophiles including enamines 3, indoles 5, pyrroles 7 and β-keto esters 9 to provide corresponding SCF2H products 4, 6, 8 and 10. The reaction of allyl alcohols 11 with 2 under the same conditions provided difluoromethylsulfinyl (S(O)CF2H) products 12, instead of SCF2H products, in good yields. These methods can be applied to the synthesis of a series of difluoromethylthiolated cyclic and acyclic β-keto esters, 1,3-diketones 10, pyrazole 13 and pyrimidine 14 by a consecutive, two-step one-pot reaction using 2 under an enamine strategy. The reactivity and reaction mechanism of 2 are discussed.

2. Results and discussion

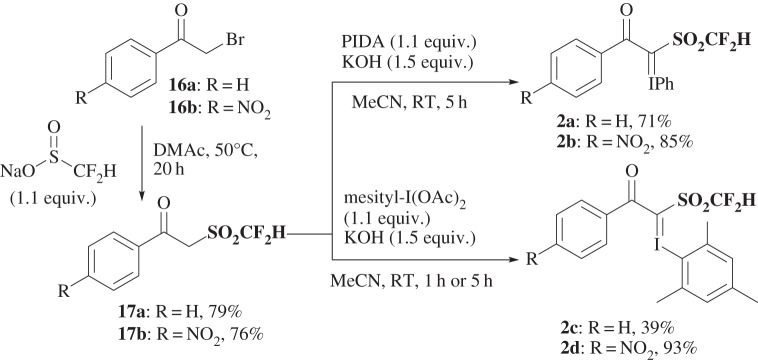

Preparation of difluoromethanesulfonyl hypervalent iodonium ylides 2 is shown in scheme 1. 2-Bromoacetophenone (16a) was treated with sodium difluoromethanesulfinate [66] in dimethyl-\break acetamide (DMAc) at 50°C for 20 h to give 2-difluoromethanesulfonylacetophenone (17a) in 79% yield. The reaction of 17a with phenyliodonium diacetate (PIDA) in the presence of potassium hydroxide provided 2a in 71% yield. Other reagents 2b, 2c and 2d were prepared using a method similar to that for 2a (scheme 1). All the reagents are crystals and stable enough for practical use, except for 2c. They can be maintained in a refrigerator (0°C). The most stable reagent is 2d and 19F-NMR-based stability of the reagents can be ranked as 2d > 2b > 2a >>> 2c (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

Scheme 1.

Preparation of difluoromethylthiolation reagents 2.

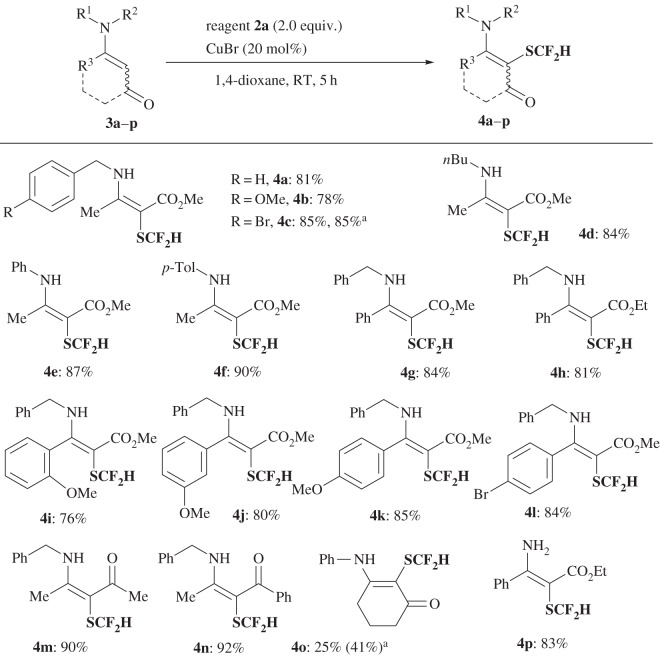

We began our study on difluoromethylthiolation with 2a using β-enamino ester 3a. After screening the reaction conditions (electronic supplementary material, table S2), a catalytic amount of Cu(I)Br (20 mol%) in 1,4-dioxane at room temperature was found to be the best set of conditions, and the difluoromethylthiolation reaction proceeded well providing α-SCF2H-β-enamino ester 4a in 94% yield (run 4, electronic supplementary material, table S2). Substrate generality for the difluoromethylthiolation of β-enamino esters 3 by 2a was investigated (scheme 2). As shown in scheme 2, a wide range of β-enamino esters 3 were found to be suitable substrates, furnishing the corresponding SCF2H-enamines 4 in high yields independent of the substitution on the nitrogen atom (benzyl, alkyl and aryl), the size of the ester group (OMe, OEt) or the enamine skeleton (methyl or aryl enamines). The reactions of enamino ketones 3m,n were also efficient under the same conditions to furnish α-SCF2H-β-enamino ketones 4m,n in 90% and 92% yield, respectively, independent of the existence of enolizable ketone. The use of cyclic enamino ketone 3o was also attempted and the desired product 4o was obtained in 25% yield, which improved slightly to 41% after using reagent 2d. In addition, N-unprotected β-enamino ester 3p was applied under the same conditions to give a high yield of 4p (83%). The structure of 4 was confirmed by 19F NMR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR and mass spectra. The X-ray crystallographic structure of 4c was analysed (CCDC 1446329; electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

Scheme 2.

Difluoromethylthiolation of enamines 3. Superscript ‘a’ denotes reagent 2d was used instead of 2a.

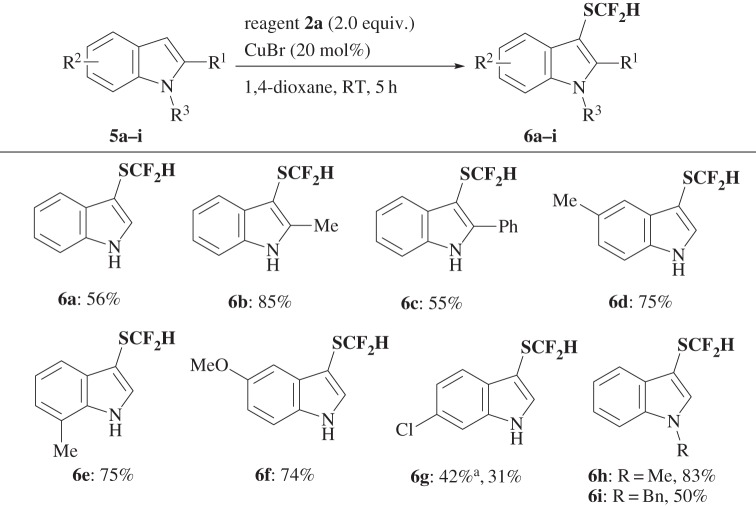

Reagent 2a was found to have wide applicability as a difluoromethylthiolation reagent not only for enamines, but also for a variety of nucleophiles, such as indoles 5 (scheme 3), pyrroles 7 (scheme 4), β-keto esters 9a–c (scheme 5) and silyl enol ether 9d (scheme 5) under the same or slightly modified conditions to provide corresponding SCF2H products 6, 8 and 10 in good yields. When yields were not satisfactory, they could be improved by using regent 2d instead of 2a, in particular, for the difluoromethylthiolation of pyrroles 7 (for optimized reaction conditions, see electronic supplementary material, table S3) and β-keto esters 9 (scheme 5).

Scheme 3.

Difluoromethylthiolation of indoles 5. Superscript ‘a’ denotes reagent 2d was used instead of 2a.

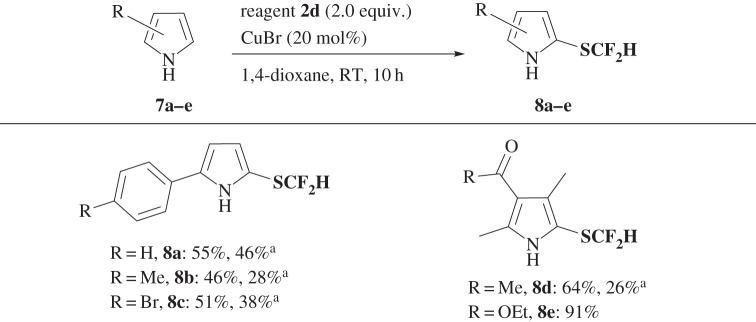

Scheme 4.

Difluoromethylthiolation of pyrroles 7. Superscript ‘a’ denotes reagent 2a was used.

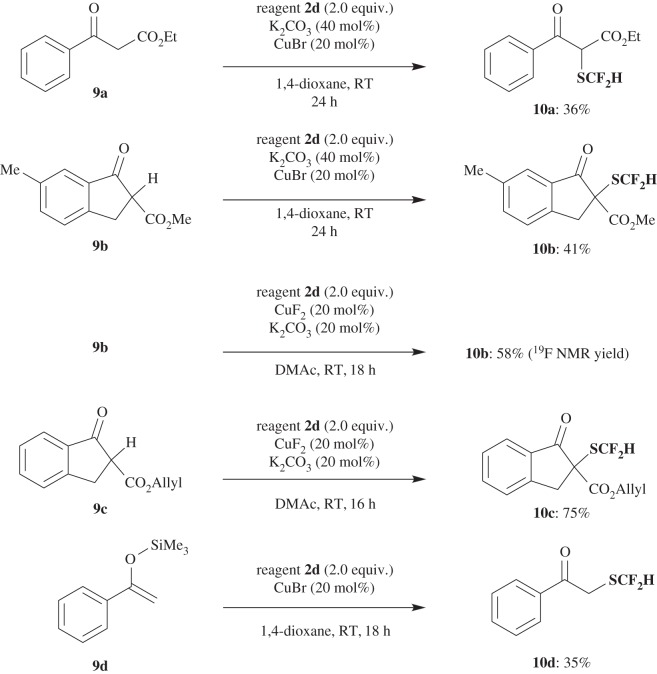

Scheme 5.

Difluoromethylthiolation of β-keto esters 9a–c and silyl enol ether 9d.

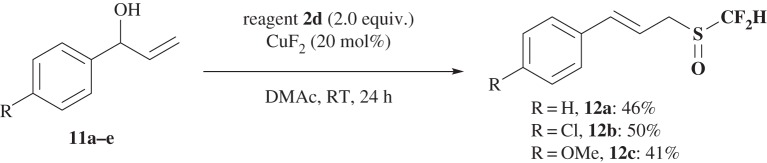

The reaction of allyl alcohol 11a with 2a under the optimized conditions of CuF2 in DMAc (see electronic supplementary material, table S4) gave a difluoromethylsulfinyl, S(O)CF2H compound 12a in moderate yield (46%) via a [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, instead of an SCF2H compound. Both the electron-donating (OMe) and electron-deficient (Cl) groups were applicable in the reaction (scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Reaction of allyl alcohols 11 with 2a.

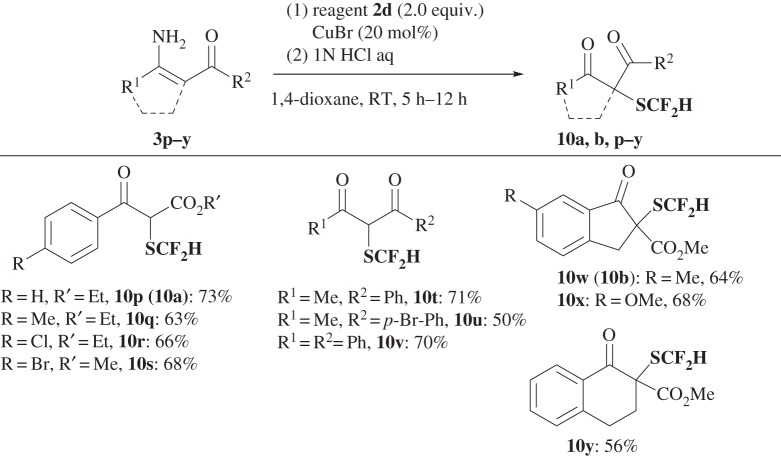

The difluoromethylthiolation reaction by 2 is particularly useful for the reaction of enamines. It should be noted that the difluoromethylthiolation of enamines, i.e. the enamine method, can be expanded to the synthesis of α-SCF2H-β-keto esters and α-SCF2H-1,3-diketones by a one-pot combination of reactions that involves difluoromethylation of unprotected, NH2-enamine esters and enamine ketones 3p–y with 2a and subsequent hydrolysis (scheme 7). A series of acyclic and cyclic α-SCF2H-β-ketoesters and α-SCF2H-1,3-diketones with a variety of substituents were obtained in high yields (10a, b, p–y: 63–73%). This enamine method has the advantage of higher yields relative to the direct reaction with β-keto esters. More importantly, acyclic α-SCF2H, β-keto esters and ketones are not prepared using the Shen reagent [61], presumably due to the lower reactivity of acyclic substrates than cyclic ones (9a–c; scheme 5).

Scheme 7.

Enamine method: two-step, one-pot synthesis of difluoromethylthiolated β-keto esters and 1,3-diketones 10 from NH2-enamines 3p–y.

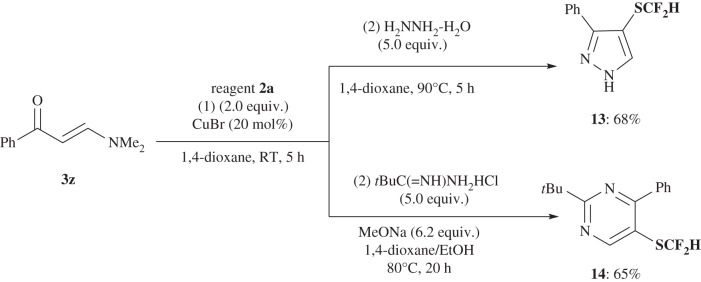

The enamine method was further extended to allow the synthesis of biologically attractive SCF2H-substituent heterocycles of pyrazole and pyrimidine by a similar two-step, one-pot, consecutive reaction procedure (scheme 8). First, enamine ketone 3z was treated with 2a in the presence of CuBr in dioxane at room temperature for 5 h. The addition of hydrazine monohydrate (5.0 equiv.) followed by heating and cyclohydration produced 4-difluoromethylthiolated pyrazole 13 in 68% yield. Similarly, the difluoromethylation of 3z with 2a followed by treatment with tert-butylcarbamidine hydrochloride (5.0 equiv.) and sodium methoxide (6.2 equiv.) under heated conditions gave 5-difluoromethylthiolated pyrimidine 14 in 65% yield.

Scheme 8.

Enamine method: two-step, one-pot synthesis of difluoromethylthiolated pyrazole 13 and pyrimidine 14 from enamine 3z.

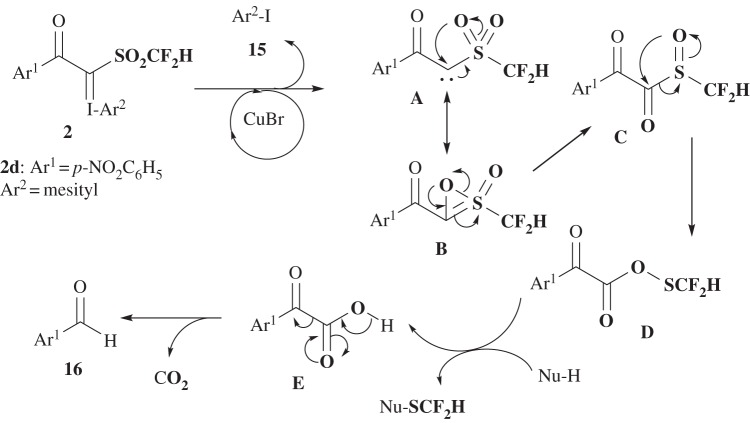

A proposed reaction mechanism of difluoromethylthiolation by reagent 2 is postulated in scheme 9. This mechanism is principally the same as a previous consecutive reaction mechanism [62,63] by SCF3-reagent 1 involving successive (i) copper-catalyzed carbene-generation A, (ii) oxathiirene-2-oxide formation B, (iii) rearrangement to sulfoxide C, and (iv) collapse to thioperoxoate D. Hence, the SCF2H thioperoxoate D is likely to be an actual species for electrophilic difluoromethylthiolation of nucleophiles via decarboxylation of E. Detection of the residues, Ar2-I 15 (Ar2 = mesityl) and Ar1CHO 16 (Ar1 = p-NO2Ph) after the reaction with reagent 2d, together with the previous mechanistic investigation using SCF3-reagent 1 [62,63], strongly support the reaction mechanism shown in scheme 9 (also see electronic supplementary material, scheme S3).

Scheme 9.

The proposed reaction mechanism.

The roles of copper catalysts, CuF2 and CuBr, depending on the substrates are not known. The Lewis acid centre of CuF2 is harder than the Lewis acid centre of CuBr; since Cu(II) is harder than Cu(I), F− is harder than Br−. The reaction mechanism in scheme 9 includes sulfur atoms with different oxidation states with different softness and hardness (from soft to hard: S, S(O) and SO2) [67], thus the catalyst of CuF2 or CuBr might also activate the different stage of each transition state. The more clear explanation should be required based on the detailed study such as molecular calculations.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, the preparation and application of novel electrophilic difluoromethylthiolation reagents 2a–d have been developed. Reagents 2 were found to be useful for the difluoromethylthiolation of a wide range of enamines, indoles, pyrroles and β-keto esters. Allylic alcohols were also reacted with 2 to provide allylic S(O)CF2H compounds via sigmatropic rearrangement. The difluoromethylthiolation of enamines (enamine method) can be widely extended to the synthesis of a variety of SCF2H-β-keto esters, 1,3-diketones, pyrazole and pyrimidine under a two-step one-pot procedure. High yields are obtained with a wide substrate scope and the reactions proceed at room temperature. This should be compared with Shen's recent papers on SCF2H transfer, which need elevated temperatures and prolonged reaction times [61] or stoichiometric amounts of a silver complex. Besides, the access to the SCF2H-β-keto esters and 1,3-diketones is more general by our reagents than the Shen reagent [61]. Because the fluorine often induces some expectation and something interesting [9,10,68–72], our new SCF2H reagents would be efficient tools for the development of novel drugs and functional materials. Further investigation of reagent 2 for the difluoromethylthiolation of other substrates, such as heteroatom nucleophiles (N-, S- or P-nucleophiles), is underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Daikin Industries Ltd for gifting a chemical for the preparation of sodium difluoromethanesulfinate.

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

S.A., O.M. and M.T. conducted and analysed the experiments and compounds. M.S. conducted X-ray crystallographic analysis and gave useful discussion. N.S. designed, directed the project and wrote the manuscript with contributions from S.A., O.M., M.T. and M.S. All authors contributed to discussions and gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research is partially supported by the Platform Project for Supporting in Drug Discovery and Life Science Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), the Advanced Catalytic Transformation (ACT-C) from the Japan Science and Technology (JST) Agency, the Kobayashi International Foundation and the Hoansha Foundation.

References

- 1.Kirsh P. 2013. Modern fluoroorganic chemistry: synthesis reactivity, applications, 2nd edn Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ojima I (ed.). 2009. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. Chichester, UK: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bégué JP, Bonnet-Delpon D (eds). 2008. Biioorganic and medicinal chemistry of fluorine. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V. 2008. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 320–330. (doi:10.1039/B610213C) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagman WK. 2008. The many roles for fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 51, 4359–4369. (doi:10.1021/jm800219f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilardi EA, Vitaku E, Njardarson JT. 2014. Data-mining for sulfur and fluorine: an evaluation of pharmaceuticals to reveal opportunities for drug design and discovery. J. Med. Chem. 57, 2832–2842. (doi:10.1021/jm401375q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beno BR, Yeung KS, Bartberger MD, Pennington LD, Meanwell NA. 2015. A survey of the role of non-covalent sulfur interactions in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 58, 4383–4438. (doi:10.1021/jm501853m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phipps RJ, Toste FD. 2013. Chiral anion phase-transfer catalysis applied to the direct enantioselective fluorinative dearomatization of phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1268–1271. (doi:10.1021/ja311798q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiehoff C, Holland MC, Daniliuc C, Houk KN, Gilmour R. 2015. Can acyclic conformational control be achieved via a sulfur–fluorine gauche effect? Chem. Sci. 6, 3565–3571. (doi:10.1039/C5SC00871A) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fustero S, Simón-Fuentes A, Barrio P, Haufe G. 2015. Olefin metathesis reactions with fluorinated substrates, catalysts and solvents. Chem. Rev. 115, 871–930. (doi:10.1021/cr500182a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Sánchez-Roselló M, Aceña JL, del Pozo C, Sorochinsky AE, Fustero S, Soloshonok VA, Liu H. 2014. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001–2011). Chem. Rev 114, 2432–2506. (doi:10.1021/cr4002879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeschke P. 2004. The unique role of fluorine in the design of active ingredients for modern crop protection. ChemBioChem 5, 570–589. (doi:10.1002/cbic.200300833) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yale HL. 1959. The trifluoromethyl group in medical chemistry. J. Med Chem 1, 121–133. (doi:10.1021/jm50003a001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang T, Neumann CN, Ritter T. 2013. Introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups. Angew. Chem Int Ed 52, 8214–8264. (doi:10.1002/anie.201206566) Angew. Chem. 125, 8372–8423 (doi:10.1002/ange.201206566) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hojczyk KN, Feng P, Zhan C, Ngai MY. 2014. Trifluoromethoxylation of arenes: synthesis of ortho-trifluoromethoxylated aniline derivatives by OCF3 migration. Angew. Chem Int Ed 53, 14 559–14 563. (doi:10.1002/anie.201409375) Angew. Chem. 126, 14 787–14 791 (doi:10.1002/ange.201409375) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toulgoat F, Alazet S, Billard T. 2014. Direct trifluoromethylthiolation reactions: the ‘Renaissance’ of an old concept. Eur. J Org Chem 2014, 2415–2428. (doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301857) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang X, Wu T, Phipps R, Phipps J, Toste FD. 2015. Advances in catalytic enantioselective fluorination, mono-, di-, and trifluoromethylation, and trifluoromethylthiolation reactions. Chem. Rev 115, 826–870. (doi:10.1021/cr500277b) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin G, Kalvet I, Englert U, Schoenebeck F. 2015. Fundamental studies and development of nickel-catalyzed trifluoromethylthiolation of aryl chlorides: active catalytic species and key roles of ligand and traceless MeCN additive revealed. J. Am Chem Soc 137, 4164–4172. (doi:10.1021/jacs.5b00538) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo S, Zhang X, Tang P. 2015. Silver-mediated oxidative aliphatic C–H trifluoromethylthiolation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 4065–4069. (doi:10.1002/anie.201411807) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu H, Xiao Z, Wu J, Guo Y, Xiao JC, Liu C, Chen QY. 2015. Direct trifluoromethylthiolation of unactivated C(sp3)–H using silver(I) trifluoromethanethiolate and potassium persulfate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 4070–4074. (doi:10.1002/anie.201411953) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weng Z, He W, Chen C, Lee R, Tan D, Lai Z, Kong D, Yuan Y, Huang KW. 2013. An air-stable copper reagent for nucleophilic trifluoromethylthiolation of aryl halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 1548–1552. (doi:10.1002/anie.201208432) Angew. Chem. 125, 1588–1592 (doi:10.1002/ange.201208432) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu C, Ma B, Shen Q. 2014. N-Trifluoromethylthiosaccharin: an easily accessible, shelf-stable, broadly applicable trifluoromethylthiolating reagent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9316–9320. (doi:10.1002/anie.201403983) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao X, Wang X, Yang T, Lu L, Shen Q. 2013. An electrophilic hypervalent iodine reagent for trifluoromethylthiolation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3457–3460. (doi:10.1002/anie.201209817) Angew. Chem. 125, 3541–3544 (doi:10.1002/ange.201209817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C, Xie Y, Chu L, Wang RW, Zhang X, Qing FL. 2012. Copper-catalyzed oxidative trifluoromethylthiolation of aryl boronic acids with TMSCF3 and elemental sulfur. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2492–2495. (doi:10.1002/anie.201108663) Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 2542–2545 (doi:10.1002/anie.201208432) Angew. Chem. 125, 1588–1592 (doi:10.1002/ange.201108663) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alazet S, Zimmer L, Billard T. 2013. Base-catalyzed electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolation of terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10 814–10 817. (doi:10.1002/anie.201305179) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang L, Qian J, Yi W, Lu G, Cai C, Zhang W. 2015. Direct trifluoromethylthiolation and perfluoroalkylthiolation of C(sp2)–H bonds with CF3SO2Na and RfSO2Na. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14 965–14 969. (doi:10.1002/anie.201508495) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tlili A, Billard T. 2013. Formation of C–SCF3 bonds through direct trifluoromethylthiolation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 6818–6819. (doi:10.1002/anie.201301438) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baert F, Colomb J, Billard T. 2012. Electrophilic trifluoromethanesulfanylation of organometallic species with trifluoromethanesulfanamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 10 382–10 385. (doi:10.1002/anie.201205156) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferry A, Billard T, Langlois BR, Bacqué E. 2009. Trifluoromethanesulfanylamides as easy-to-handle equivalents of the trifluoromethanesulfanyl cation (CF3S+): reaction with alkenes and alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 8551–8555. (doi:10.1002/anie.200903387) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pluta R, Nikolaienko P, Rueping M. 2014. Direct catalytic trifluoromethylthiolation of boronic acids and alkynes employing electrophilic shelf-stable N-(trifluoromethylthio)phthalimide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1650–1653. (doi:10.1002/anie.201307484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu F, Shao X, Zhu D, Lu L, Shen Q. 2014. Silver-catalyzed decarboxylative trifluoromethylthiolation of aliphatic carboxylic acids in aqueous emulsion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 6105–6109. (doi:10.1002/anie.201402573) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang CP, Vicic DA. 2012. Nickel-catalyzed synthesis of aryl trifluoromethyl sulfides at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 183–185. (doi:10.1021/ja210364r) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C, Chu L, Qing FL. 2012. Metal-free oxidative trifluoromethylthiolation of terminal alkynes with CF3SiMe3 and elemental sulfur. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 12 454–12 457. (doi:10.1021/ja305801m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu JB, Xu XH, Chen ZH, Qing FL. 2015. Direct dehydroxytrifluoromethylthiolation of alcohols using silver(I) trifluoromethanethiolate and tetra-n-butylammonium iodide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 897–900. (doi:10.1002/anie.201409983) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang T, Lu L, Shen Q. 2015. Iron-mediated Markovnikov-selective hydro-trifluoromethylthiolation of unactivated alkenes. Chem. Commun 51, 5479–5481. (doi:10.1039/C4CC08655D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams DJ, Goddard A, Clark JH, Macquarrie DJ. 2000. Trifluoromethylthiodediazoniation: a simple, efficient route to trifluoromethyl aryl sulfides. Chem. Commun 987–988. (doi:10.1039/B002560G) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li M, Guo J, Xue XS, Cheng JP. 2016. Quantitative scale for the trifluoromethylthio cation-donating ability of electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolating reagents. Org. Lett 18, 264–267. (doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03433) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teverovsky G, Surry DS, Buchwald S. 2011. Pd-catalyzed synthesis of Ar–SCF3 compounds under mild conditions. Angew. Chem Int Ed 50, 7312–7314. (doi:10.1002/anie.201102543) Angew. Chem. 123, 7450–7452 (doi:10.1002/ange.201102543) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leroux F, Jeschke P, Schlosser M. 2005. α-Fluorinated ethers, thioethers, and amines: anomerically biased species. Chem. Rev 105, 827–856. (doi:10.1021/cr040075b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu XH, Matsuzaki K, Shibata N. 2015. Synthetic methods for compounds having CF3–S units on carbon by trifluoromethylation, trifluoromethylthiolation, triflylation, and related reactions. Chem. Rev 115, 731–764. (doi:10.1021/cr500193b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ni C, Hu M, Hu J. 2015. Good partnership between sulfur and fluorine: sulfur-based fluorination and fluoroalkylation reagents for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev 115, 765–825. (doi:10.1021/cr5002386) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Hu J. 2005. Facile synthesis of chiral α-difluoromethyl amines from N-(tert-butylsulfinyl)aldimines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5882–5886. (doi:10.1002/anie.200501769) Angew. Chem. 117, 6032–6036 (doi:10.1002/ange.200501769) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brahms DLS, Dailey WP. 1996. Fluorinated carbenes. Chem. Rev 96, 1585–1632. (doi:10.1021/cr941141k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langlois BR. 1988. Improvement of the synthesis of aryl difluoromethyl ethers and thioethers by using a solid-liquid phase-transfer technique. J. Fluorine Chem 41, 247–261. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hine J, Porter JJ. 1960. Methylenes as intermediates in polar reactions. XXI. A sulfur-containing methylene. J. Am Chem Soc 82, 6118–6120. (doi:10.1021/ja01508a036) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deprez P, Vevert JP. 1996. Synthesis of difluoromethylthio imidazole from methylthio imidazole. J. Fluorine Chem 80, 159–162. (doi:10.1016/S0022-1139(96)03497-5) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zafrani Y, Sod-Moriah G, Segall Y. 2009. Diethyl bromodifluoromethylphosphonate: a highly efficient and environmentally benign difluorocarbene precursor. Tetrahedron 65, 5278–5283. (doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.082) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, Wang F, Hu J. 2009. N-Tosyl-S-difluoromethyl-S-phenylsulfoximine: a new difluoromethylation reagent for S-, N-, and C-nucleophiles. Org. Lett 11, 2109–2112. (doi:10.1021/ol900567c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L, Wang F, Ni C, Hu J. 2013. Synthesis of gem-difluorocyclopropa(e)nes and O-, S-, N-, and P-difluoromethylated compounds with TMSCF2Br. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12 390–12 394. (doi:10.1002/anie.201306703) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metha VP, Greaney MF. 2013. S-, N-, and Se-Difluoromethylation using sodium chlorodifluoroacetate. Org. Lett 15, 5036–5039. (doi:10.1021/ol402370f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuchibe K, Bando M, Takayama R, Ichikawa J. 2015. Organocatalytic, difluorocarbene-based S-difluoromethylation of thiocarbonyl compounds. J. Fluorine Chem 171, 133–138. (doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2014.08.013) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen QY, Wu SW. 1989. A simple convenient method for preparation of difluoromethyl ethers using fluorosulfonyldifluoroacetic acid as a difluorocarbene precursor. J. Fluorine Chem 44, 433–440. (doi:10.1016/S0022-1139(00)82808-0) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deng XY, Lin JH, Zheng J, Xiao JC. 2015. Difluoromethylation and gem-difluorocyclopropenation with difluorocarbene generated by decarboxylation. Chem. Commun 51, 8805–8808. (doi:10.1039/C5CC02736E) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujiwara Y, Dixon JA, Rodriguez RA, Baxter RD, Dixon DD, Collins MR, Blackmond DG, Baran PS. 2012. A new reagent for direct difluoromethylation. J. Am Chem Soc 134, 1494–1497. (doi:10.1021/ja211422g) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Surya Prakash GK, Zhang Z, Wang F, Ni C, Olah GA. 2011. N,N-Dimethyl-S-difluoromethyl-S-phenylsulfoximinium tetrafluoroborate: a versatile electrophilic difluoromethylating reagent. J. Fluorine Chem 132, 792–798. (doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2011.04.023) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang W, Zhu JM, Hu J. 2008. Electrophilic (phenylsulfonyl)difluoromethylation of thiols with a hypervalent iodine(III)–CF2SO2Ph reagent. Tetrahedron Lett. 49, 5006–5008. (doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.06.064) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bayarmagnai B, Matheis C, Jouvin K, Goosen LJ. 2015. Synthesis of difluoromethyl thioethers from difluoromethyl trimethylsilane and organothiocyanates generated in situ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 5753–5756. (doi:10.1002/anie.201500899) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jouvin K, Mathesis C, Goossen LJ. 2015. Synthesis of aryl tri- and difluoromethyl thioethers via a C–H-thiocyanation/fluoroalkylation cascade. Chem. Eur J 21, 14 324–14 327. (doi:10.1002/chem.201502914) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fier PS, Hartwig JF. 2013. Synthesis of difluoromethyl ethers with difluoromethyltriflate. Angew. Chem Int Ed 52, 2092–2095. (doi:10.1002/anie.201209250) Angew. Chem. 125, 2146–2149 (doi:10.1002/ange.201209250) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu J, Gu Y, Leng X, Shen Q. 2015. Copper-promoted Sandmeyer difluoromethylthiolation of aryl and heteroaryl diazonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7648–7652. (doi:10.1002/anie.201502113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu D, Gu Y, Lu L, Shen Q. 2015. N-Difluoromethylthiophthalimide: a shelf-stable, electrophilic reagent for difluoromethylthiolation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10 547–10 553. (doi:10.1021/jacs.5b03170) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang YD, Azuma A, Tokunaga E, Yamamoto M, Shiro M, Shibata N. 2013. Trifluoromethanesulfonyl hypervalent iodonium ylide for copper-catalyzed trifluoromethylthiolation of enamines, indoles, and β-keto esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 8782–8785. (doi:10.1021/ja402455f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang Z, Yang YD, Tokunaga E, Shibata N. 2015. copper-catalyzed regioselective trifluoromethylthiolation of pyrroles by trifluoromethanesulfonyl hypervalent iodonium ylide. Org. Lett. 17, 1094–1097. (doi:10.1021/ol503616y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arimori S, Takada M, Shibata N. 2015. Trifluoromethylthiolation of allylsilanes and silyl enol ethers with trifluoromethanesulfonyl hypervalent iodonium ylide under copper catalysis. Org. Lett. 17, 1063–1065. (doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arimori S, Takada M, Shibata N. 2015. Reactions of allyl alcohols and boronic acids with trifluoromethanesulfonyl hypervalent iodonium ylide under copper-catalysis. Dalton Trans. 44, 19 456–19 459. (doi:10.1039/C5DT02214B) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.He Z, Tan P, Ni C, Hu J. 2015. Fluoroalkylative aryl migration of conjugated N-arylsulfonylated amides using easily accessible sodium di- and monofluoroalkanesulfinates. Org. Lett. 17, 1838–1841. (doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00308) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kice JL, Kasperek GJ, Patterson D. 1969. Relative nucleophilicity of some common nucleophiles toward sulfonyl sulfur. Nucleophile-catalyzed hydrolysis and other nucleophilic substitution reactions of aryl α-disulfones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91, 5516–5522. (doi:10.1021/ja01048a020) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soloshonok VA, Ueki H, Yasumoto M, Mekala S, Hirschi JS, Singleton DA. 2007. Phenomenon of optical self-purification of chiral non-racemic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12 112–12 113. (doi:10.1021/ja065603a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Soloshonok VA. 2006. remarkable amplification of the self-disproportionation of enantiomers on achiral-phase chromatography columns. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 766–769. (doi:10.1002/anie.200503373) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Hagan D. 2012. Organofluorine chemistry: synthesis and conformation of vicinal fluoromethylene motifs. J. Org. Chem. 77, 3689–3699. (doi:10.1021/jo300044q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buissonneaud DY, Mourik TV, O'Hagan D. 2010. A DFT study on the origin of the fluorine gauche effect in substituted fluoroethanes. Tetrahedron 66, 2196–2202. (doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.01.049) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tavasli M, O'Hagan D, Pearson C, Petty MC. 2002. The fluorine gauche effect. Langmuir isotherms report the relative conformational stability of (±)-erythro- and (±)-threo-9,10-difluorostearic acids. Chem. Commun. 1226–1227. (doi:10.1039/B202891C) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.