Abstract

Alcohol use during young adulthood may reflect a learning process whereby positive and negative alcohol-related experiences and interpretations of those experiences drive subsequent behavior. Understanding the effect of consequences and the evaluation of consequences could be informative for intervention approaches.

Objective

To examine the extent to which the number of positive and negative alcohol consequences experienced and the evaluation of those consequences predict subsequent alcohol use and consequences in college students.

Method

Students at three colleges (N = 679) completed biweekly web-based surveys on alcohol use, positive and negative consequences, and consequence evaluations for two academic years. Hierarchical linear modeling tested whether consequences and evaluations in a given week predicted changes in alcohol use and consequences at the next assessment. Moderation by gender and class year also were evaluated.

Results

Evaluating past-week negative consequences more negatively than one’s average resulted in decreases in alcohol use at the next assessment. More negative evaluation of negative consequences was followed in the subsequent observation by a higher number of positive consequences for females but not males. A higher number of positive consequences in a given week was followed by a higher number of both positive and negative consequences in the subsequent observation. Number of negative consequences experienced and evaluation of positive consequences had no effect on later behavior.

Conclusions

Salient negative consequences may drive naturalistic reductions in alcohol use, suggesting the possible efficacy of programs designed to increase the salience of the negative effects of alcohol.

Keywords: alcohol consequences, evaluations, college alcohol use

There are a host of problem outcomes that are associated with alcohol use among college students, including physiological, social, and academic harms (Hingson et al., 2009). The volume and severity of these consequences drive local, regional and national efforts to reduce problem alcohol use among college students (Correia et al., 2012; NIAAA, 2002), but rates of heavy drinking and associated consequences in this high-risk population have remained stable for at least two decades (Johnston et al., 2013).

Different theories have been used to explain the development of problematic alcohol use. Behavioral learning theory posits that behavior is a function of reinforcement, whereby behavior that results in positive experiences (e.g., feeling buzzed) is reinforced and more likely to recur, whereas behavior that results in aversive experiences (e.g., vomiting) is less likely to recur. In the college alcohol research literature, learning theory is supported by evidence that the experience of positive and negative consequences of drinking is associated with subsequent drinking behavior. For example, there is evidence that different negative alcohol-related consequences predict distinct drinking trajectories (Read et al., 2007; 2012), and that experiencing a higher number of negative consequences predicts lower alcohol use and problems years later (White & Ray, 2014). There is evidence as well that positive consequences influence subsequent alcohol use; Park, Kim and Sori (2013) recently demonstrated that higher frequency of positive consequences prospectively predicted greater heavy drinking.

Beyond whether the number of consequences experienced influences subsequent behavior, there is evidence that the way those consequences are interpreted is relevant. Cognitive theories, including cognitive/behavioral theory, the theory of reasoned action, and the theory of planned behavior posit that cognitions are central and proximal influences on specific behaviors. Indeed, evidence is emerging that the extent to which consequences are rated as aversive contributes to whether an individual reports being ready to make changes to his or her drinking (Barnett et al., 2002; 2003; 2006; Longabaugh et al., 1995). Two studies conducted with college students (Gaher & Simons, 2007; Mallett et al., 2008) found evidence that less negative evaluations of negative consequences were positively associated with alcohol use. However, both studies evaluated the cross-sectional association between evaluations and drinking, Gaher and Simons (2007) measured evaluations of hypothetical consequences (not evaluations of consequences recently experienced by participants), and Mallett et al. (2008) measured typical drinking patterns not actual drinking episodes. Reports collected closer in time to the drinking behavior are considered to be more accurate than summaries of drinking in retrospective reports (Gmel & Rehm, 2004), and reports of typical drinking are likely to underrepresent more extreme drinking episodes (Del Boca & Darkes, 2003). Moreover, we cannot infer from this retrospective work whether evaluations of recent alcohol-related consequences influence later drinking behavior.

Research examining associations between subjective evaluations and drinking behavior in college students found that less negative evaluation of negative (physical/behavioral) drinking consequences in one semester was prospectively associated with a higher number of negative alcohol problems, but not alcohol use in the next semester (Patrick & Maggs, 2011). Patrick and Maggs also found that positive evaluations of positive (fun/social) consequences predicted alcohol use but not alcohol problems. Thus, there is some indication that evaluations of both negative and positive consequences are related to subsequent behavior across short timeframes. However, Patrick and Maggs measured participant evaluations of hypothetical consequences, and these evaluations were conducted in the middle of the study, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the effects of evaluations on later behavior. In contrast to the findings in Patrick and Maggs, White and Ray (2014; other results above) found that higher “bother” scores for negative consequences did not predict alcohol use or consequences seven years later. Although longitudinal, and therefore better able to support the notion that evaluations influence later behavior, these two studies are limited in that evaluations were hypothetical (Patrick & Maggs, 2011) and the measurement interval between evaluation of consequences and subsequent alcohol use was long (White & Ray, 2014), limiting the conclusions that can be drawn about associations between consequence evaluations and subsequent behavior.

A recent investigation directly addressed the question about whether aversive experiences influence future drinking. Using a prospective design in a sample of college students, Merrill and colleagues (Merrill et al., 2013) investigated the link between evaluations of negative consequences (i.e., aversiveness) reported one week and the drinking and consequences experienced the subsequent week. This study established that consequences perceived as particularly negative by a student were followed by downward changes in both alcohol use and negative consequences. However, when evaluations were used to predict subsequent negative consequences, the amount of alcohol consumed in the same week was not controlled, thus making it unclear whether the effect of the evaluations on the number of subsequent consequences was a function of reduced drinking. Controlling for same-week alcohol use would provide greater precision about the unique effects of evaluations on the subsequent experience of consequences, allowing for an understanding of whether the way recent consequences are perceived explains variance in the experience of future consequences above and beyond how much one drinks. If evaluations of negative consequences lead to changes in the experience of future consequences after controlling for alcohol use, it might suggest that alcohol-related risk behaviors were reduced (even if consumption was not) and/or that protective behavioral strategies were adopted. Merrill et al. also only measured participants over a period of 10 weeks, and it is important to establish whether the effects of consequences and their evaluations are reliable when examined over a longer period. Additionally, Merrill et al. used the peak evaluation (i.e., the most negative evaluation across all consequences reported in a week) in their analyses. It is possible that different findings would result from averaging evaluation scores across consequences experienced, which is perhaps a better representation of one’s entire experience. Finally, this study included only juniors and seniors, so it is unclear if the findings would be relevant for younger (underage) students.

In summary, prior research has shown that the way consequences of drinking are personally perceived may influence whether or not students make changes in their drinking behavior. Understanding the natural process of change that follows positive and negative alcohol experiences would inform the improvement of college alcohol interventions, most of which include discussion about prior alcohol consequences (Ray et al., 2014). However, research in the area of evaluations of consequences and their importance for alcohol use has been limited by small samples, cross-sectional designs and in some cases retrospective summaries of drinking. In addition, as noted above, behavioral learning theory considers both positive and negative experiences to be important in the reinforcement of behavior, and both types of experiences can result from the same drinking episode; we therefore believe it is essential that the experience of positive and negative consequences and their evaluations be included together in investigations purporting to investigate behavior change. Using a longitudinal prospective design with advanced analytic approaches may provide an improved understanding of the complex interrelationships between the experience of and perceptions about positive and negative alcohol-related consequences.

It is also possible that the association between consequence evaluations and later drinking behavior depends on individual differences, such as gender and class year. White and Ray (2014) found that women rated consequences as more bothersome than men, and there is evidence as well that college women are more reactive than men to receiving alcohol-related sanctions (Carey & DeMartini, 2010). Therefore, it is possible that women are more likely than men to change their behavior in response to negative alcohol consequences. There is also evidence that that younger students are less accepting of negative alcohol consequences (DeMartini et al., 2011) and that youth with less experience with alcohol consequences are more reactive to negative consequences (Barnett et al., 2002; 2006; 2008) and so may be more likely to change their drinking in response to particularly negative alcohol-related experiences. These possible differences by gender or class year can be studied as moderators, that is, the effect of consequence evaluations on subsequent alcohol use may be moderated by gender and age and therefore might suggest adjustments to intervention approaches.

Study Aims

The primary purpose of the current study was to investigate the effect of alcohol consequences and the evaluations of those consequences on later alcohol use and consequences to improve our understanding of putative mechanisms of naturalistic behavior change. In a longitudinal investigation with first- and second-year college students, we investigated whether positive and negative alcohol consequences and evaluations of those consequences in a given week predicted changes in subsequent alcohol use and consequences. In line with behavioral learning and cognitive theories, we expected that experiencing a higher number of negative consequences and showing higher weekly aversiveness ratings (i.e., evaluations) of negative consequences would predict less drinking and a lower number of negative consequences in subsequent observations. We also expected that experiencing a higher number of positive consequences and evaluating those consequences more positively would predict greater subsequent drinking and a higher number of positive consequences. We also investigated gender and class year as moderators of the effects of consequence evaluations on later behavior. We expected that women would be more responsive to aversive consequences than men would, and that students would be more responsive to aversive consequences in their first than in their second year of college. Finally, we extended previous work by examining both average and peak consequence evaluation scores.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a study of 1,053 (57.5% female) students at three college sites, recruited prior to the start of their first year. The study had a multisite, multicohort, longitudinal design and collected regular observations of alcohol use and both positive and negative consequences across the first- and second-year of college (Barnett et al., 2013; 2014; Hoeppner et al., 2012). Participants were omitted from the present study if they did not report drinking (n = 241; 22.9%) or if they reported drinking without negative consequences (n = 122; 11.6%) over the course of the study. An additional 11 (1.0%) participants were deleted listwise for missing data on variables of interest, leaving a final sample of N = 679. Participants were on average 18.36 years old (SD = 0.46) at baseline. The sample was 60.1% (n = 408) female and 11.0% (n = 75) Latino/Hispanic. Participants were 71.9% (n = 488) White, 9.6% (n = 65) Asian-American, 5.9% (n = 40) Black, and 6.0% (n = 41) Multiracial; 6.6% (n = 45) indicated “other” or did not indicate a race (most of these participants reported Latino/Hispanic ethnicity).

Procedures

Incoming students at three colleges/universities in southern New England were included in this study. During the summer prior to the start of each academic year in three consecutive years, a random sample of incoming freshmen from each site was invited to enroll. Racial/ethnic minority students were oversampled. Sampled students received an invitation by mail and email; parents of minor students received a separate mailing and their consent was required before these students could enroll. Following enrollment, participants completed a baseline survey online and were randomly assigned to one of two biweekly assessment groups. Each week, starting with the first week of the first year of college, one of the two alternating groups received an email containing a link to a brief assessment. These assessments were conducted during the two academic years and over the winter breaks, but not during the summer months. For each participant, there were 18 possible assessments in each year (8 in each semester, 2 over winter break), for 36 possible assessments. Participants were compensated $20 for the baseline survey, $2 for every completed biweekly survey, a bonus of $20 if 7 of the 8 surveys in that semester were completed, and a chance to receive a $100 payment upon submission of each biweekly survey. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating sites.

Measures

The baseline survey contained items measuring gender and race/ethnicity.

Alcohol use: Number of drinks per week

The biweekly survey collected number of standard drinks on each day in the past week, using an automatically produced past-week diary grid based on the day the survey was completed. On each survey, participants were provided the definition of a standard drink (12 oz. beer or wine cooler, 5 oz. wine, 1.5 oz. liquor in a shot or mixed drink). The number of drinks in each week was summed.

Alcohol consequences

On each biweekly survey, participants were asked, “In the past week did you have any of the following experiences during or after drinking alcohol?” followed by a set of 23 alcohol-related consequences (11 positive items, 13 negative items; see Table 1). These consequences were chosen from well-established measures of positive and negative outcomes of alcohol use (Fromme et al., 1993; 1997; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992; Kahler et al., 2005; Leigh & Stacy, 1993; Noar et al., 2003; Saunders et al., 1993). Consequences were assessed only for participants who reported one or more drinking days in the week. Numbers of endorsed positive and negative alcohol-related consequences were separately summed for each week. See Barnett et al. (2014) for additional information about this measure.

Table 1.

Subjective evaluations of negative and positive consequences

| Consequence | Evaluation M (SD)a | Number of times reported (% of 12,919 drinking weeks reported) |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Consequences | ||

|

| ||

| I disappointed others that are close to me | 1.85 (0.80) | 841 (6.5%) |

| I drove after drinking and realized I should not have | 1.74 (0.89) | 337 (2.6%) |

| I got into trouble with my school authorities or police | 1.71 (1.02) | 149 (1.1%) |

| I felt sad or depressed | 1.71 (0.70) | 1342 (10.4%) |

| I got physically sick (e.g. vomit, stomach cramps) | 1.70 (0.78) | 1699 (13.2%) |

| I said something that I wish I hadn’t | 1.68 (0.75) | 1471 (11.4%) |

| I had a romantic or sexual activity that I now regret | 1.62 (0.80) | 746 (5.8%) |

| I had problems with school work | 1.59 (0.83) | 806 (6.2%) |

| I passed out | 1.45 (0.91) | 495 (3.8%) |

| I couldn’t remember some part of the day or night | 1.31 (0.77) | 2212 (17.1%) |

| I accidentally physically hurt someone | 1.21 (0.87) | 148 (1.1%) |

| I was physically injured | 1.15 (0.83) | 418 (3.2%) |

| I got into a physical fight | 0.98 (0.99) | 142 (1.1%) |

| Average negative evaluation score | 1.48 (0.83) | |

|

| ||

| Positive Consequences | ||

|

| ||

| I had a good time | 2.42 (0.60) | 10,258 (79.4%) |

| I enjoyed sex more | 2.32 (0.67) | 920 (7.1%) |

| I talked to someone I was attracted to | 2.13 (0.60) | 5126 (39.7%) |

| I felt less stressed or more relaxed | 2.10 (0.55) | 6547 (50.7%) |

| I was more energetic | 2.04 (0.59) | 4719 (36.5%) |

| It was easier to socialize | 2.04 (0.57) | 6375 (49.3%) |

| I felt like I was part of the group | 2.02 (0.62) | 4357 (33.7%) |

| I was able to take my mind off problems | 1.97 (0.64) | 3664 (28.4%) |

| I felt more sexy | 1.97 (0.68) | 2068 (16.0%) |

| I felt more self-confident and sure of myself | 1.94 (0.68) | 3919 (30.3%) |

| I expressed my thoughts or feelings to someone more easily | 1.73 (0.62) | 2907 (22.5%) |

| Average positive evaluation score | 2.14 (0.62) | |

Note. Negative consequence evaluation: How much did this experience bother you? Positive consequence evaluation: How enjoyable was this experience? 0 = Not at all; 1 = A little; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Very much.

Evaluation of consequences

For each consequence endorsed, participants recorded how much they enjoyed (for positive consequences) or were bothered by (for negative consequences) each consequence, using a 4-point scale with response options 0 (not at all), 1 (a little), 2 (somewhat), and 3 (very much). Average positive and negative evaluation scores were calculated for each week. It is possible that an individual’s most extreme evaluations of negative consequences are more influential on subsequent behavior than the average of his/her evaluations (C. L. Park, 2004), and Merrill et al (2013) used the highest (i.e., peak) negative evaluation in each week. To allow for comparison to prior work, positive and negative consequences with the highest ratings in each week also were identified.

Data Analytic Plan

Data preparation and analytic approach

Prior to running analytic models, outcome variables were lagged to allow for the prediction of behavior from one assessment to the next. A multilevel person-period dataset was created with observations representing the 36 possible assessments nested within the final sample of 679 persons.

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was used to address the primary aims of the proposed study – to examine the prediction of next assessment time point drinking behavior from previous time point number of consequences and evaluations of consequences. HLM was an ideal approach as it (1) allowed examination of within-person associations (i.e., whether subjective evaluations of consequences determine subsequent level of drinking on one week as compared to another), while providing natural controls for between-person differences (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), and (2) can accommodate when spacing between observations and number of observations vary by participant.

Model testing using HLM 6.0 (Raudenbush et al., 2004), began with tests of fully unconditional models to determine intraclass correlations (ICCs) for all three outcome variables – next assessment number of drinks, negative consequences, and positive consequences. Subsequently, both Level 1 and Level 2 predictors were added (described below). At Levels 1 and 2, all continuous variables were person-centered and grand-mean centered, respectively (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Person-centering at Level 1 results in a score representing the deviation from one’s own average score on that variable. This allows for examining the difference in a variable relative to oneself rather than relative to others in the sample, consistent with our theoretical focus on intraindividual change. Grand-mean centering at Level 2 controls for how an individual differs from others on between-person variables.

Across models, intercept and slope effects were specified as random to allow for individual differences in mean levels of use and consequences and slopes of predictors on use and consequences. Prior to forming interactions, dichotomous variables (gender, class year) were recoded using effects coding, to remove collinearity with interaction terms and so that all effects could be evaluated in the context of significant interactions (Aiken & West, 1991). Final models were tested for violations of the assumptions of HLM. A square-root transformation was applied to outcome variables representing number of drinks and negative consequences to resolve their non-normal distributions and to address a violation of normality of Level 1 residuals; positive consequences were normally distributed. Potential violations of homogeneity of variance were addressed by reliance on robust standard errors (Zeger et al., 1988), which should be trustworthy given the large number of participants.

Predicting change in alcohol use (weekly number of drinks) (Model 1)

In the alcohol use outcome model, we included the following time-varying variables of primary interest at Level 1: prior assessment week’s number of negative consequences, number of positive consequences, and subjective evaluation scores of both negative and positive consequences. We controlled for previous week number of drinks and year in school, and for week of the semester, and whether a given assessment fell during the school year vs. winter break (given prior findings that drinking changes over the course of the semester and differs between the academic year and school breaks; Hoeppner et al., 2012). We modeled interactions at L1 to test whether class year (Level 1) would moderate the time-varying effects of negative or positive evaluations on subsequent alcohol use.

At Level 2, predictors of the intercept represent predictors of average levels of the outcome variable across the course of the study. Level 2 predictors of the intercept of number of drinks included gender, race/ethnicity (0 = non-White; 1 = non-Hispanic White), mean number of positive and negative consequences per week, mean positive evaluation of positive consequences, and mean negative evaluation of negative consequences. Including these mean variables allowed us to differentiate the influence of consequences and evaluations at the weekly level from the influence of individual differences (between -person) in these variables across time. Given minor differences in cohorts, we also controlled for participant cohort (1–3), and for school site (1–3), given prior findings of differences in alcohol use between sites (Barnett et al., 2013; 2014). Finally, we included gender at Level 2 as a predictor of the slope effects of negative and positive evaluations on subsequent alcohol use to test whether the time-varying effect of evaluations varied by gender.

Predicting change in number of alcohol consequences (Models 2 and 3)

Identical models were used to predict negative and positive consequences separately. These models were similar to the alcohol use model; however, since number of positive and negative consequences were the outcome, mean number of positive and negative consequences were not included as Level 2 predictors. Alcohol consequence models also included a Level 1 control for the number of drinks consumed at the same assessment that consequences were measured.

Results

Response Rates

The average number of 36 potential biweekly surveys completed was 31 (SD = 8). Across a possible 24,444 points of data collection (679 participants x 36 assessment time points), 20,949 (85.7%) were completed. To estimate slope effects of evaluations from one assessment to alcohol use behavior at the next, two consecutive observations of data are required. Out of a possible 23,765 consecutive assessment pairs (679 students x 35 pairs); we observed 19,767 (83%). When a participant does not have data on two consecutive assessments that assessment pair cannot contribute to the statistical estimation of slope effects, however, all assessments contribute to intercept estimation.

Descriptives

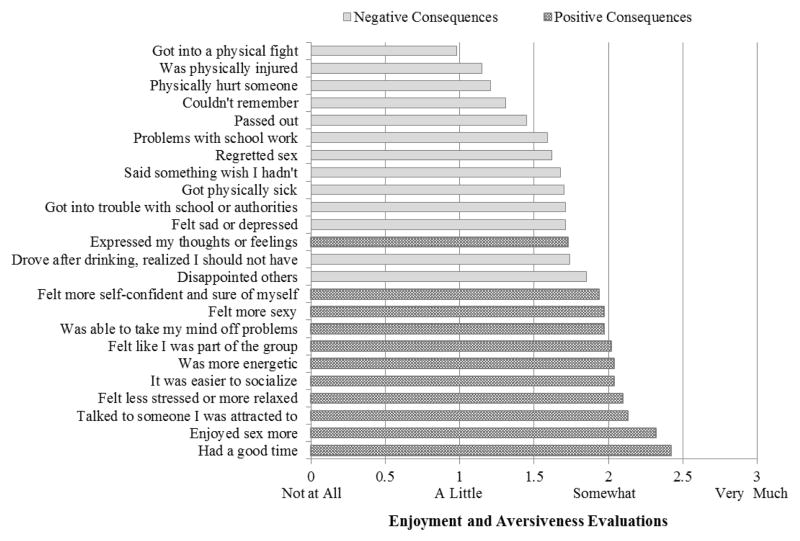

On average, participants reported drinking on 1.85 days per week (SD = 0.76), consuming 6.13 (SD = 8.73) drinks per week and experiencing 0.84 negative consequences (SD = 1.37) and 3.93 positive consequences (SD = 2.93) each week. Men drank at higher levels (M = 7.99 drinks per week, SD = 10.63) than women (M = 4.92, SD = 6.98); t(20,925) = 25.24, p < .001. Alcohol use was reported on 12,919 (61.7%) of the 20,949 weekly assessments completed, and 5,225 (40.4%) assessments on which alcohol use was reported were characterized by at least one negative consequence, while 11,018 (85.3%) were characterized by at least one positive consequence. See Table 1 for mean negative and positive evaluation ratings by consequence, number of assessment weeks on which each consequence was reported, and percent of drinking weeks on which each consequence was experienced. Positive consequences were rated more positively than negative consequences were rated negatively. Indeed, there was little overlap in the ratings scale, with negative consequences rated on average between “a little” and “somewhat” aversive, while average positive consequence ratings hovered around “somewhat” enjoyable (see Figure 1). Table 2 has correlations among the consequence and evaluation variables, at both the within-person (bi-weekly) level and between-person (averaged across weeks) level. The differences in the between- and within-person correlations suggest that it is important to investigate these variables at both within- and between-person levels.

Figure 1.

Evaluation ratings of negative and positive consequences. Consequences were rated on a scale from 0 to 3, with a high rating reflecting a more enjoyable experience for positive consequences and a more aversive experience for negative consequence.

Table 2.

Correlations among number and evaluations of positive and negative consequences

| Number of Neg Cons | Number of Pos Cons | Evaluation of Neg Cons | Evaluation of Pos Cons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Neg Cons | 1.0 | .45*** | .03 | −.05 |

| Number of Pos Cons | .34*** | 1.0 | −.05 | .05 |

| Evaluation of Neg Cons | −.10*** | .07*** | 1.0 | .10** |

| Evaluation of Pos Cons | .17*** | −.10*** | −.07*** | 1.0 |

Note: Within-person (bi-weekly assessment scores) correlations are below the diagonal and between-person (average scores across all weeks) are above the diagonal.

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

In fully unconditional models, we examined the proportion of total variation in weekly number of drinks and consequences at each of the two levels of analysis by calculating intraclass correlations (ICCs). Within-person differences (Level 1) accounted for 58%, 78%, and 61% of the variance in weekly drinks, negative consequences, and positive consequences, respectively; between-person differences (Level 2) accounted for the remaining variance (42%, 22%, and 39%, respectively). Thus, most of the variability in both use and consequences was attributable to how participants differ from themselves across time.

Model 1: Predicting Change in Alcohol Use

Table 3 presents biweekly-level (i.e., within-person, Level 1) predictors of alcohol use followed by person-level (i.e., between-person, Level 2) predictors of alcohol use. Of primary interest for this analysis is the L1 effect of negative evaluations of negative consequences on subsequent drinking. This effect is quantified by calculating the amount of change in alcohol consumed for each unit of deviation between the prior assessment’s evaluations and the individual’s average evaluation score, holding all other model variables constant. Supporting our hypothesis, a higher average subjective negative evaluation score predicted lower alcohol consumption in the subsequent assessment (p < .001). Specifically, in any one week, the more aversive a person’s negative consequences were relative to his/her average evaluations, the fewer drinks he/she was likely to drink in the next observation.

Table 3.

Prediction of number of drinks in a week (Model 1)

| Predictors | B (SE) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept of alcohol use | 1.44 (0.29) | 4.90 | .000 |

| Biweekly-level (L1) predictors of alcohol use | |||

| Prior assessment negative evaluationa | −0.10 (0.03) | −3.32 | .000 |

| Negative evaluations x Class year | 0.13 (0.07) | 1.86 | .063 |

| Prior assessment positive evaluationa | 0.08 (0.05) | 1.72 | .086 |

| Positive evaluations x Class year | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.28 | .782 |

| Prior assessment number of negative consequencesa | −0.04 (0.02) | −1.75 | .082 |

| Prior assessment number of positive consequencesa | 0.01 (0.01) | 1.16 | .249 |

| Prior assessment sum of drinksa | 0.02 (0.004) | 5.46 | .000 |

| Week of semester | −0.06 (0.01) | −5.93 | .000 |

| School year week (vs. break) | 0.24 (0.15) | 1.60 | .110 |

| Class year | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.46 | .644 |

| Person-level (L2) predictors of alcohol use (intercept effects) | |||

| Gender | −0.65 (0.09) | −6.91 | .000 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.42 (0.10) | 4.30 | .000 |

| School | 0.14 (0.07) | 1.98 | .048 |

| Cohort | 0.06 (0.06) | 1.11 | .267 |

| Average negative evaluation across weeks | −0.27 (0.09) | −2.91 | .004 |

| Average positive evaluation across weeks | 0.52 (0.11) | 4.85 | .000 |

| Average number of positive consequences across weeks | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.72 | .475 |

| Average number of negative consequences across weeks | 0.63 (0.07) | 8.75 | .000 |

| Person-level (L2) moderators of evaluation effects (slope effects) | |||

| Gender x (L1) negative evaluations | 0.06 (0.06) | 1.01 | .314 |

| Gender x (L1) positive evaluations | 0.12 (0.10) | 1.23 | .219 |

Note. Gender (0.4= female, −0.6 = male), Race/Ethnicity (0 = Non-White, 1 = Non-Hispanic White); three School sites coded 1–3; three Cohorts coded 1–3; School Year Week (0 = Break Week, 1 = School Year Week); Class Year (−0.5 = First-Year, 0.5 = Sophomore); removal of cross-level interaction effects of gender (L2) on evaluations (L1) did not alter the pattern or significance of model findings

Person-centered variable that reflects deviations from the participant’s average score on that variable across weeks.

Bold values are significant at p < .05.

On the other hand, L1 positive evaluations of positive consequences did not predict changes in drinking at the next observation. Further, the number of negative consequences experienced did not predict changes in subsequent drinking, nor did the number of positive consequences experienced. Class year did not moderate the extent to which negative or positive evaluations at one assessment predicted number of drinks in the next assessment, and men and women did not differ on how evaluations of consequences related to subsequent assessment number of drinks. Additional Level 1 and Level 2 effects are listed in Table 3.

Model 2: Predicting Change in the Number of Negative Alcohol Consequences Experienced

As can be seen in Table 4 (left), neither negative nor positive evaluations of consequences at Level 1 predicted the number of negative consequences experienced at the subsequent assessment. Class year did not moderate this effect, and the association between evaluations and negative consequences did not differ by gender.

Table 4.

Prediction of number of negative and positive alcohol consequences (Models 2 and 3)

| Model 2: Predicting Negative Consequences | Model 3: Predicting Positive consequences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Predictors | B (SE) | t | p | B (SE) | t | p |

| Intercept of consequences | 1.34 (0.13) | 10.43 | .000 | 6.24 (0.56) | 11.09 | .000 |

| Biweekly-level (L1) predictors of consequences | ||||||

| Prior assessment negative evaluationa | −0.001 (0.02) | −0.11 | .910 | 0.06 (0.05) | 1.32 | .188 |

| Negative evaluations x Class year | 0.06 (0.03) | 1.85 | .064 | −0.01 (0.11) | −0.14 | .892 |

| Prior assessment positive evaluationa | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.85 | .396 | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.18 | .858 |

| Positive evaluations x Class year | 0.05 (0.05) | 1.00 | .316 | −0.03 (0.16) | −0.22 | .828 |

| Prior assessment number of negative consequencesa | −0.01 (0.01) | −1.00 | .320 | 0.04 (0.03) | 1.41 | .160 |

| Prior assessment number of positive consequencesa | 0.03 (0.01) | 4.29 | .000 | 0.15 (0.02) | 6.38 | .000 |

| Concurrent assessment number of drinksa | 0.04 (0.00) | 17.62 | .000 | 0.12 (0.01) | 16.34 | .000 |

| Week of semester | −0.01(0.01) | −1.61 | .108 | −0.14 (0.02) | −7.41 | .000 |

| School year week (vs. break) | −0.09 (0.07) | −1.22 | .223 | 0.08 (0.22) | 0.36 | .721 |

| Class year | −0.11 (0.03) | −4.43 | .000 | −0.69 (0.09) | −7.51 | .000 |

| Person-level (L2) predictors of consequences(intercept effects) | ||||||

| Gender | 0.06 (0.04) | 1.52 | .129 | 0.21 (0.19) | 1.12 | .265 |

| Race/Ethnicity | −0.08 (0.05) | −1.58 | .114 | 0.14 (0.21) | 0.67 | .505 |

| School | −0.17 (0.03) | −5.74 | .000 | −0.36 (0.15) | −2.43 | .015 |

| Cohort | −0.03 (0.03) | −1.19 | .235 | −0.36 (0.12) | −2.93 | .004 |

| Average negative evaluation across weeks | 0.05 (0.04) | 1.29 | .197 | −0.07 (0.18) | −0.36 | .720 |

| Average positive evaluation across weeks | −0.11 (0.05) | −2.32 | .021 | 0.17 (0.22) | 0.76 | .434 |

| Person-level (L2) moderators of evaluation effects(slope effects) | ||||||

| Gender x (L1) negative evaluations | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.44 | .660 | 0.27(0.10) | 2.85 | .005 |

| Gender x (L1) positive evaluations | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.33 | .744 | 0.20 (0.15) | 1.30 | .193 |

Note. Alcohol use was the sum of past week number of drinks. Gender (0.4 = female, −0.6 = male); Race/Ethnicity (0 = Non-White, 1 = Non-Hispanic White); three School sites coded 1–3; three Cohorts coded 1–3; School Year Week (0 = Break Week, 1 = School Year Week); Class Year (−0.5 = First-Year, 0.5 = Sophomore); removal of cross-level interaction effects of gender (L2) on evaluations (L1) did not alter the pattern or significance of model findings

Person-centered variable that reflects deviations from the individual’s average score on that variable across weeks.

Bold values are significant at p < .05.

In contrast, experiencing a higher number of positive consequences during the prior assessment week predicted experiencing a higher number of negative consequences in the next observation. However, a higher number of negative consequences during the prior assessment week did not predict a higher number of negative consequences in the next observation.

Model 3: Predicting Change in the Number of Positive Alcohol Consequences Experienced

As shown in Table 4 (right), neither positive evaluations of positive consequences nor negative evaluations of negative consequences were significantly predictive of the number of positive consequences experienced in the next observation. However, there was an interaction between negative evaluations and gender (i.e., an effect of gender on the slope of negative evaluations on positive consequences). Probing this interaction revealed that for females, higher negative evaluations were associated with a greater number of positive consequences at the following assessment (B = .17, SE = .06, t = 2.67, p = .008) but for males, negative evaluations were not predictive of positive consequences at the following assessment (B = −.10, SE = .07, t = −1.37, p = .171). There was no other evidence of moderation in these models.

At Level 1, higher numbers of positive consequences experienced at one assessment predicted higher numbers of positive consequences at the following assessment. Higher numbers of negative consequences experienced did not predict subsequent number of positive consequences.

Models without Covariates

In the interest of investigating the importance of our primary predictors without covariates, we reran Models 1 (predicting alcohol use), 2 (predicting negative consequences), and 3 (predicting positive consequences) in two ways: (1) with number of negative and positive consequences but without evaluations (or interactions with evaluations) as predictors, and (2) with evaluations, but not number of negative and positive consequences. The only model of these six that differed in results from models in which covariates were included was the prediction of alcohol use (Model 1), when only number of consequences and not evaluations of consequences were included. In this analysis, more positive consequences at one assessment predicted more alcohol use at the following assessment, p < .001). We interpret this as providing evidence for the relative importance of evaluations over number of (positive) consequences. That is, when evaluations are not accounted for, positive consequences appear to significantly predict later drinking; but when evaluations are covaried, positive consequences are not significant, suggesting that the evaluations account for more of the unique variance in subsequent drinking.

Peak Evaluations as an Alternative to Average Evaluations

To test whether results differed when the most extreme evaluation was used rather than the average of the evaluations, and to compare our results to previous findings (Merrill et al., 2013), we re-ran all of the above models using peak evaluations and found no differences in the significance of Level 1 effects.

Discussion

This investigation followed three cohorts of college students from three different college sites using multiple brief assessments over two academic years to investigate how the experience of alcohol-related consequences and the evaluations of those consequences influenced subsequent behavior, while controlling several potentially influential or confounding variables. Strengths of the study include demographic diversity, frequent assessment intervals, and excellent survey completion rates. Consistent with our expectations, higher average aversiveness of negative alcohol-related consequences predicted subsequent reductions in drinking. Importantly, the evaluation of negative consequences, but not the total number of (either negative or positive) consequences experienced in a given week, was uniquely related to drinking in the next observation. Thus, we conclude that the way one interprets one’s negative alcohol-related experiences, not their sheer number, has the most importance for subsequent drinking. The pattern of findings for the effect of negative evaluations on later alcohol consequences was quite different from the alcohol use model. Higher negative evaluations were unrelated to number of negative consequences in the next observation after controlling for alcohol use. Therefore, although evaluating recent consequences negatively may result in reducing one’s subsequent drinking, students do not seem to experience fewer negative consequences as a function of those prior negative evaluations.

We observed an interesting effect of gender on the evaluations of negative consequences, whereby for women, more negative evaluations of negative consequences were associated with a greater number of positive consequences at the next assessment, with no such association for men. That is, while we observed a reduction in drinking across both genders as a function of higher negative evaluations, this reduction in drinking did not result in a similar impact on positive consequences for the two genders. It may be that the reduction in drinking that follows from aversive negative consequences results in women having a more positive time on subsequent occasions, whereas men have no such reaction. This finding requires replication and our tentative interpretation requires additional research. Even so, it highlights the importance of considering positive and negative consequences in the same investigation and the importance of investigating gender differences in the effect of consequence evaluations on alcohol outcomes.

Positive evaluations of positive consequences were not predictive of subsequent alcohol use or number of negative or positive consequences. We can conclude, therefore, that positive evaluations of one’s drinking experiences do not have a direct relationship with subsequent drinking, or with negative or positive outcomes, at least when controlling for negative evaluations and number of negative and positive consequences. This is contrary to theory that would suggest that experiencing enjoyable alcohol-related effects would predict subsequent increases in alcohol-related behavior, and to other work that found positive associations between positive evaluations and alcohol use (Patrick & Maggs, 2011). Our exploratory analyses suggest that positive evaluations are not predictive even when negative consequences and positive consequences are removed (see results), or when negative evaluations are removed (analyses not presented), suggesting the lack of significance is not a function of overlapping variance in these constructs. Nevertheless, given the contradiction of our findings with theory and prior research, future work should continue to investigate the effects of positive consequences and their evaluations over time, including within the context of negative consequences/evaluations, to develop an improved understanding of the learning processes in young adult drinkers.

The number of positive consequences experienced in a week was associated with the subsequent experience of both positive and negative consequences. It is notable that the relationship between positive consequences and subsequent positive and negative consequences was observed even after controlling for alcohol use, suggesting that the increase in consequences in the subsequent observation was not driven solely by changes in drinking. It may be that having a higher than typical number of positive consequences on one occasion (i.e., many good things happened) reinforces the pursuit of these consequences for subsequent occasions, regardless of level of drinking. Furthermore, if students are seeking out the experience of positive consequences (e.g., feeling more sexy, enjoying sex more), they may also be more likely to encounter negative ones (e.g., regretted sexual activity). The fact that we also found that positive consequences were much more frequent than negative consequences raises concern about positive reinforcement for alcohol use. Specifically, positive consequences are frequent and valued so provide a consistent context for decisions about future drinking.

Overall, the findings from our alcohol use and consequence models were quite distinct, with evaluations of negative consequences showing primary relevance for subsequent alcohol use, and the number of positive consequences showing primary importance for the increase in consequences of both types. It is possible that one’s recollections of the negative experiences of recent drinking episodes (i.e., one’s evaluations of aversiveness) are most relevant for (proximal) subsequent decisions about drinking, but that the experience of a higher number of positive consequences drive individuals toward seeking these positive experiences, which may lead as well to negative consequences.

We did not find that students in their first year of college were more responsive to evaluations of consequences; none of our models found a significant interaction between class year and evaluations. We did however find a main effect whereby students reported more consequences in their first year of college than in their second. This latter finding supports the general greater concern for first-year students, the need to understand their experiences with alcohol, and the importance of targeted prevention approaches prior to college or early in the first year (Borsari et al., 2007; Wechsler et al., 1994). Despite important differences found in drinking behaviors between class years (Barnett et al., 2013), it may not be optimal to use class year as a proxy for alcohol experience; further research should consider how actual prior experience with alcohol is associated with response to alcohol-related consequences.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of prior work that used longitudinal methods. Four prior studies are relevant. First, the finding that negative interpretations of negative consequences are important in reducing subsequent alcohol use replicate work by Merrill et al. (2013); we also extended their findings by showing significant effects even when positive consequences and their evaluations were controlled. The current study and Merrill et al.’s previous work also used different measures of alcohol consequences and consequence aversiveness, suggesting that the effect of negative evaluations on subsequent alcohol use is robust. Second, our findings are partially consistent with Patrick and Maggs (2011) who found negative evaluations of negative consequences were associated with greater alcohol problems but not alcohol use one semester later (we found an association with alcohol use not problems), but unlike Patrick and Maggs we did not find that positive evaluations of consequences were relevant for subsequent behavior. Third, our finding that positive consequence experiences were predictive of subsequent positive consequences is partially consistent with other work that found positive consequences were related to subsequent heavy drinking (A. Park et al., 2013). These consistent but somewhat different outcomes may be due to different measurement approaches and analytic methods. Finally, our findings contrast with those of White and Ray (2014) who found that the experience, but not the evaluation of consequences predicted later behavior, but we note that study used between-person analyses and examined the association over a 7-year interval; these methodological and time-interval differences may make the comparison with our findings inappropriate. Our analytic models, in contrast, controlled between-person levels of evaluations and consequences, and therefore the findings reflect individual within-person fluctuations across weeks of the study. In summary, our findings and prior work indicate there are meaningful effects of alcohol-related consequences and their evaluations on subsequent alcohol use. Greater differences between our work and other research are seen when between vs. within-subjects analyses were conducted, and when the intervals between observations were larger. Finally, although not a primary goal of this study, we found that using the peak evaluation instead of the average of evaluations in a week as the predictor showed similar outcomes. We therefore both replicated and extended previous work (Merrill et al., 2013) which used the peak evaluation score.

It is important to note that we do not have an objective indication of the severity of the alcohol consequences we measured and, like other research, we calculated sums for positive and negative consequences, in effect weighing each consequence equally on intensity/severity. However, some consequences are likely more intense or severe than others. Our approach also assumed that the variation in evaluation scores was a function of individual differences in appraisals or differences within an individual on different occasions. We therefore assumed that differences in evaluations of consequences between and/or within our participants were a function of different perceptions of the severity or intensity of the consequences they experienced, and concluded that it was these perceptions that were responsible for the reduction in alcohol use. However, participants may have reduced their drinking as a function of the actual (differential) severity of their consequence. In other words, whereas we framed the evaluation findings as representing differences in interpretation of experiences, we cannot dispute that they may also reflect objective differences in consequence severity. It is likely that both of these effects are active. These different interpretations have obvious implications for assessment and intervention research and we hope future work will account for both.

Limitations

Assessments were every other week so the most immediate change following a drinking week was not captured. The analytic lag that was tested was from one two-week interval to the next, so the persistence of change beyond that interval cannot be assumed, but our findings provide valuable insight into more immediate experiential processes through which changes in alcohol use occur. Consequences were measured at the week level so evaluations reflected an average of the week’s experiences, not experiences associated with a particular drinking episode. However, the modal number of drinking days in a week in this sample was one, so in these weeks, the consequences were directly associated with the one and only day of drinking. Number of consequences was a weekly count of different experiences; since each consequence was counted only once, the same consequence experienced multiple times in a week would be underrepresented. Evaluations were measured on a unidirectional scale, which assumed negative consequences were aversive and positive consequences were enjoyable. There is evidence however, that consequences that are categorized as “negative” may be evaluated by some drinkers as neutral or even enjoyable (Mallett et al., 2008). We suggest future investigations use scales that measure the entire dimension from enjoyment to aversiveness for all consequences. Our participants were from three college sites in the Northeast and results may not generalize to other regions. Participants also were in their first two years of college so results may not generalize to other class years, although findings are very consistent with Merrill and colleagues who investigated only upperclassmen (Merrill et al., 2013). Finally, our primary interest was in studying the effects of negative consequences and their evaluations, so the minority of drinkers (representing about 1 in 10) who reported no negative consequences was not included. Given their lack of negative consequences, these drinkers are a lower-risk group, but their experiences with alcohol and its effects may be informative to investigate.

Future Directions and Implications

The variability in ratings of different (positive and negative) consequences suggests that different consequences are likely to promote different levels of change on average and, as noted above, may be objectively different in intensity/severity. This, as well as our distinctly different findings when considering evaluations and consequences as predictors, suggests that both consequence type and cognitive evaluations of alcohol consequences are important and warrant further investigation. A related area for future research is to elucidate differences in the evaluation of different consequences. For example, given our between-person findings (Level 2) for several of the evaluation terms, it is possible that individual differences (e.g., sensation seeking, impulsivity, alcohol expectancies) or time-varying variables (e.g., affect) are associated with differences in evaluations on average or during a drinking event. In addition, evaluations of the same consequence experienced on different days will differ within a person depending on the context, and the balance between positive and negative alcohol consequences within an event is likely influential for subs equent drinking. On a related point, the evaluation of negative consequences may depend on the evaluation of positive consequences (whereby bad experiences are less aversive when positive experiences are more enjoyable). Future research should consider these possible interdependencies of consequence evaluations. Approaches that utilize ecological momentary assessment methods would better capture the immediate effects of specific consequences, their evaluations, and the contextual factors of individual drinking episodes. Resulting information about between- and within-person differences would have implications for more personalized intervention approaches.

Alcohol outcome expectancies may provide an alternative and/or additional explanation for the decreases in drinking following particularly aversive negative consequences. For example, after blacking out, a student may think that a blackout is more likely to happen if he/she drinks in a similar fashion again and so may decide to reduce consumption. It might be that the combination of “I think blacking out is going to happen” and “It was aversive to black out” would most strongly predict the downward change in drinking, a possibility that would be consistent with the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action.

There are a number of ways in which the findings from this study could be incorporated into prevention and intervention efforts. Focusing prevention campaigns and intervention efforts on how to interpret positive and negative alcohol consequences could be worthwhile. For example, judging from the evaluations of negative consequences in Table 1, college students may not understand the seriousness of passing out or blacking out. Programs devised to increase students’ concern about negative consequences might be beneficial. In individual brief motivational interventions, personalized feedback commonly includes information about the negative consequences participants have experienced (Carey et al., 2007; Ray et al., 2014), the purpose of which is to motivate individuals to avoid future consequences. However, providing feedback on consequences that are actually viewed by a student as neutral or positive may not have the expected effect, and may even reinforce the student’s belief that no change is warranted. Thus, one suggestion is that the assessment conducted prior to such interventions includes an evaluation scale along with the measure of negative consequences. Then when providing feedback only those negative consequences viewed as particularly bothersome to the student could be reviewed, since our findings indicate that these consequences are more likely to lead to reductions in alcohol use.

In summary, this investigation of early college students found the negative evaluations of alcohol consequences had independent effects on subsequent drinking, suggesting that these evaluations are important for reducing drinking. In addition, having a higher number of positive consequences led to experiencing more consequences of both kinds, which could be explained by the positive reinforcement of positive consequences. Findings were consistent with social learning and cognitive behavioral theories and suggest that harnessing the natural influence of one’s personal experiences and modifying interpretations about those experiences may be an effective approach for changing problematic alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA013970 and T32AA007459)

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Borsari B, Hustad JTP, Tevyaw TO, Colby SM, Kahler CW, et al. Profiles of college students mandated to alcohol intervention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(5):684–694. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Clerkin EM, Wood MW, Monti PM, Tevyaw TO, Corriveau D, et al. Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(1):103–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Goldstein AL, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. “I’ll never drink like that again”: Characteristics of alcohol-related incidents and predictors of motivation to change in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(5):754–763. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Lebeau-Craven R, O’Leary TA, Colby SM, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, et al. Predictors of motivation to change after medical treatment for drinking-related events in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16(2):106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Monti PM, Cherpitel C, Bendtsen P, Borges G, Colby SM, et al. Identification and brief treatment of alcohol problems with medical patients: An international perspective. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:262–270. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057123.36127.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Orchowski LM, Read JP, Kahler CW. Predictors and consequences of pregaming using day- and week-level measurements. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(4):921–933. doi: 10.1037/a0031402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP. Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: Implications for prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(10):2062–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, DeMartini KS. The motivational context for mandated alcohol interventions for college students by gender and family history. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(3):218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia CJ, Murphy JG, Barnett NP. College Student Alcohol Abuse: A Guide to Assessment, Intervention, and Prevention. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: State of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, Carey KB, Lao K, Luciano M. Injunctive norms for alcohol-related consequences and protective behavioral strategies: Effects of gender and year in school. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(4):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Katz EC, Rivet K. Outcome expectancies and risk-taking behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1997;21(4):421–442. doi: 10.1023/a:1021932326716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot E, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gaher RM, Simons JS. Evaluations and expectancies of alcohol and marijuana problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(4):545–554. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G, Rehm J. Measuring alcohol consumption. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2004;31:467–540. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs Suppl. 2009;(16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner BB, Barnett NP, Jackson KM, Colby SM, Kahler CW, Monti PM, et al. Daily college student drinking patterns across the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(4):613–624. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41(2):49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2012: Volume 2, College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(7):1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stacy AW. Alcohol outcome expectancies: Scale construction and predictive utility in higher order confirmatory models. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(2):216–229. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Minugh PA, Nirenberg TD, Clifford PR, Becker B, Woolard R. Injury as a motivator to reduce drinking. Academic Emergency Medicine. 1995;2:817–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Are all negative consequences truly negative? Assessing variations among college students’ perceptions of alcohol related consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(10):1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Barnett NP. The way one thinks affects the way one drinks: Subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences predict subsequent change in drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(1):42–51. doi: 10.1037/a0029898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. NIH publication # 02-5010. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2002. A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U.S. colleges. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Laforge RG, Maddock JE, Wood MD. Rethinking positive and negative aspects of alcohol use: Suggestions from a comparison of alcohol expectancies and decisional balance. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(1):60–69. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Kim J, Sori ME. Short-term prospective influences of positive drinking consequences on heavy drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(3):799–805. doi: 10.1037/a0032906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(2):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL. College students’ evaluations of alcohol consequences as positive and negative. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R, Toit M. HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Non-linear Modeling. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ray AE, Kim SY, White HR, Larimer ME, Mun EY, Clarke N, et al. When less is more and more is less in brief motivational interventions: Characteristics of intervention content and their associations with drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(4):1026–1040. doi: 10.1037/a0036593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE, Ouimette P, White J, Swartout A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms predict alcohol and other drug consequence trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(3):426–439. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Isaac NE, Grodstein F, Sellers DE. Continuation and initiation of alcohol use from the first to the second year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(1):41–45. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Ray AE. Differential evaluations of alcohol-related consequences among emerging adults. Prevention Science. 2014;15(1):115–124. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang K, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]