Abstract

Background

Previous research studies have focused on the recipients of interruptions because of the negative impact interruptions have on task performance. It is equally important to understand the initiators of interruptions to help design strategies to lessen the number of interruptions and the possible negatives consequences. The purpose of this study was to examine MDs and RNs as initiators and recipients of interruptions.

Methods

This was an instrumental case study using the shadowing method. A convenience sample of five attending trauma MDs and eight RNs were observed during the 0700–1500 and 1500–2100 shifts in the trauma section of a level one trauma center.

Result

Seventy hours of observations were recorded. Initiator and recipient of an interruption emerged as major roles during categorization of the notes. Medical doctors and RNs were found to be the recipient of an interruption more frequently than the initiator. Findings from this study indicate that MDs and RNs initiate interruptions most often through face-to-face interactions and use of the telephone.

Conclusions

A role-based taxonomy of interruptions was derived from the recorded notes. Strategies to successfully manage interruptions must consider both the role of initiator as well as the recipient when an interruption occurs. It is suggested that the role-based taxonomy presented in this paper be used to classify interruptions in future studies.

Keywords: Interruption, workflow, emergency medicine, taxonomy

1. Introduction

The emergency department (ED) is filled with a plethora of beeping pagers, ringing telephones, alarms and alerts from various medical devices, unscheduled arrival of patients, supplies not being readily available, and unexpected conversations with colleagues. These examples can interrupt the psycho-motor or cognitive workflow of the medical doctors (MDs) and registered nurses (RNs) working in a level one trauma center.

An interruption is defined as a break in the performance of a human activity initiated by a source internal or external to the recipient, with the occurrence situated within the context of a setting or location. This break results in the suspension of the initial task in order to begin the performance of an unplanned task with the assumption that the initial task will be resumed [1]. Medical doctors and RNs are the recipients of many interruptions during a shift resulting from face-to-face interactions with co-workers, telephone calls, email messages, and alarms and alerts from medical devices. These interruption examples depict a role-based event between a recipient and an initiator. The recipient takes the role by accepting the interruption. Consequently, the recipient is negatively affected by the interruption event because of the unexpected intrusion of a secondary task. For that reason, research studies in healthcare have examined the role of recipient because of the negative impact on their task performance [2–6]. Moreover, the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) [7–9], the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [10, 11] and Morbidity and Mortality [12] report that interruptions contribute to preventable medical errors. Thus, it is equally important to understand the role of both the initiator and the recipient.

The initiator has the role of initiating an interruption in either the psycho-motor or cognitive workflow of the recipient. Psycho-motor workflow entails the motor actions used to perform a task. Cognitive workflow involves thinking, problem solving, and information processing. To successfully interrupt the recipient’s workflow, the initiator must present a detectable physical signal to the recipient announcing an impending interruption. Furthermore, it can be argued that the initiator assumes that the recipient is passive and will immediately accept the interruption. Therefore, a successful interruption depends on the detection and acceptance of the impending interruption task by the recipient [1].

A review of the literature found a limited number of studies that specifically consider the role of initiator of interruptions [3, 4, 13, 14]. Coiera and Tombs categorize a communication interruption as either sent or received for nine different MD and RN clinical roles. Findings reported by Coiera and Tombs show that RNs initiated more paging and telephone calls than they received. In contrast, MDs initiated almost all communication interruptions using the telephone. Medical doctors designated as house officers initiated more telephone calls when compared to consultants, senior registrars, or senior house officers. Specifically in the ED, Spencer and Logan categorized a communication interruption as sent or received by MDs and RNs [13]. The MDs were classified as either registrars or junior medical officers. Registered nurses were categorized as either coordinators or having a patient load [13]. Findings from the study showed that clinicians in higher-ranking roles of registrars and coordinators were more often the recipient of interruptions than RNs with patient loads and junior medical officers. The studies, however, provide few details of how MDs and RNs assumed the role as initiators of interruptions.

Most recently, Sevdakus, Healey, and Vincent [15] identified the initiators and recipients of interruptions in the operating room (OR) during communication interruptions. In the OR, surgeons were found most likely to initiate an interruption when compared to anesthetists and RNs. Surgeons were also the recipients of interruptions more often than either anesthetists or RNs. More detail is needed to further describe and characterize when RNs, surgeons, and anesthetists are initiators of interruptions. Therefore, the purpose of this instrumental case study was to examine the roles of MDs and RNs working in a level one trauma center as initiators and recipients of interruptions. An understanding of the initiator will help in the design of strategies to reduce or mitigate the negative outcomes of interruptions.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The design was an instrumental case study using the shadowing method. An instrumental case study is used to gain an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon as well as to generalize from an observational, inductive approach [16]. Shadowing is a qualitative method of direct observations. The observer unobtrusively records the what, when, where, and how the subjects perform their tasks in the real world.

2.2. Subjects

A convenience sample of five MDs and eight RNs working the 0700–1500 and 1500–2100 shifts were invited to participate. A domain expert in emergency medicine identified these shifts as periods of high-interruption. Participation was voluntary.

2.3. Ethical approval and informed consent

Approval was obtained from The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects for the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston prior to initiating the study.

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to beginning an observation. In addition, community consent was obtained from the ED staff. Community consent entails meeting with the people of a specific community such as an ED to explain the risks and benefits of the study [17]. Prior to beginning the study, the observers met with the MDs and RNs to explain the study. Community consent was extended to include the ED charge nurse or attending physician giving permission for the observers to conduct the observation at the beginning of each observation.

2.4. Setting

All observations were made in the trauma section of a level one trauma center academic hospital. The hospital is part of a major medical center located in the Gulf Coast region of the United States of America (USA). The ED occupies 51,000 square feet (4738 square meters) and contains major trauma and cardiac resuscitation rooms.

2.5. Data Collection

Observers typically worked in teams of two and recorded their observations using a semi-structured note form (Fig. 1.) directly to Tablet PCs. The Tablet PCs were equipped with handwriting recognition software which directly transcribed the hand-written notes to word-processed Microsoft Word® documents. Each task was time stamped using the insert time function in Microsoft Word®. Therefore, observations were sequentially recorded on a minute-by-minute basis.

Fig. 1.

Semi-structured form.

The MDs and RNs were shadowed by the observers who recorded tasks performed by the subjects. The recorded observations included: behaviors, interactions with other hospital staff, patients, and other people, as well as the use of any artifacts such as computers and software applications, medical devices, medications, and paper medical records. In this study a task was defined as “actions that can or should be performed by one or more people to achieve a goals” [18]. Additionally, the tasks were limited to those visible to the observers.

Subjects were shadowed for a minimum of 2 hours but not more than 12 hours per session. Recording of observations began once the subject had completed the informed consent.

2.6 Data Analysis

Analysis of data was completed through a triangulation of qualitative and quantitative methods. Triangulation of methods is used to achieve a more comprehensive analysis of the phenomenon under investigation [19]. Data analysis of the notes was supported by using NVivo© [20] and MacSHAPA© [21]. All recorded observational notes for each subject were saved as a rich text format document (rtf) and uploaded into NVivo©. The Hybrid Method to Categorize Interruptions and Activities (HyMCIA) [22] was used to categorize the recorded notes. HyMCIA was developed through the hybridization of a deductive a priori classification framework with the provision of adding new categories discovered inductively in the data using grounded theory [23]. Each recorded task was analyzed, compared to the task list, and categorized using the task list provided by the MDs and RNs. As a new task was identified and categorized from the recorded observational notes, the task list was updated.

Each recorded task was further analyzed to determine if an interruption had occurred and if the subject to took role of recipient or initiator. Two coders analyzed the data for agreement of the categorization of tasks and interruptions. A percent agreement score was calculated at 99.48 percent [24].

3. Results

3.1. Categorization of recorded notes

The roles of initiator and recipient of interruptions were two themes that emerged during categorization of the notes. Table 1 shows examples of coded notes.

Table 1.

Coded recorded notes for MD and RN observations

| Coded Notes | Role Category |

|---|---|

| RN initiates a telephone call. | Initiator |

| RN initiates a telephone call but no answer. | Initiator Blocked |

| RN initiates a telephone call and put on hold. | Initiator Delayed |

| MD paged for new trauma patient. | Intended Recipient |

|

MD talking with resident when resident is interrupted to speak with the RN. |

Indirect Recipient |

| MD answers telephone but call is for the RN. | Unintended Recipient |

|

Nurse practitionerwaits until MDacknowledges her to receive report for a patient. |

Recipient Delayed |

|

RN waits to talk with MD but leaves after a few minutes. MD did not acknowledge. |

Recipient Blocked |

The precise roles that were identified are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

A role-based taxonomy of interruption

| Initiator Role | Recipient Role |

|---|---|

|

Initiator - a person who initiates an interruption |

Intended Recipient - the person to be interrupted |

|

Indirect Recipient – the incidental recipient of an interruption; i.e., talking with another in conversation when the intended recipient suspends the original activity |

|

|

Unintended Recipient - not the intended recipient of an interruption; i.e., receiving a phone call that was incorrectly dialed |

|

|

Initiator Blocked - the initiator is blocked from initiating an interruption |

Recipient Blocked - the intended recipient does not accept the interruption |

|

Initiator Delayed - the initiator is delayed in initiating an interruption |

Recipient Delayed - the intended recipient postpones an interruption |

The coded notes provided context for developing the definition for each role.

3.2. Quantification of recorded notes

Quantitative results of the recorded notes are shown in Table 3. Five attending, senior, supervising, faculty trauma MDs were observed. Of the five physicians, four were males and one was a female. The MDs were pre-selected based on scheduling and a willingness to participate. Eight RNs were shadowed. Of the eight RNs, two were male and six were female. The charge nurse for the shift pre-selected which subject would participate.

Table 3.

Results of analysis of the recorded observations

| Clinical Profession |

n | Hours of Observation |

Total Number of Interruptions |

Total Number of Tasks |

Interruptions per Hour |

Tasks per Hour |

Percent of Tasks Interrupted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDs | 5 | 30 h | 328 | 1302 | 10.58 | 42 | 25.19 |

| RNs | 8 | 40 h | 380 | 2310 | 9.5 | 57.75 | 16.45 |

The attending MDs performed fewer tasks but were interrupted more frequently than RNs. The MDs functioned primarily in a supervisory and teaching role whereas the RNs were engaged primarily in providing direct patient care.

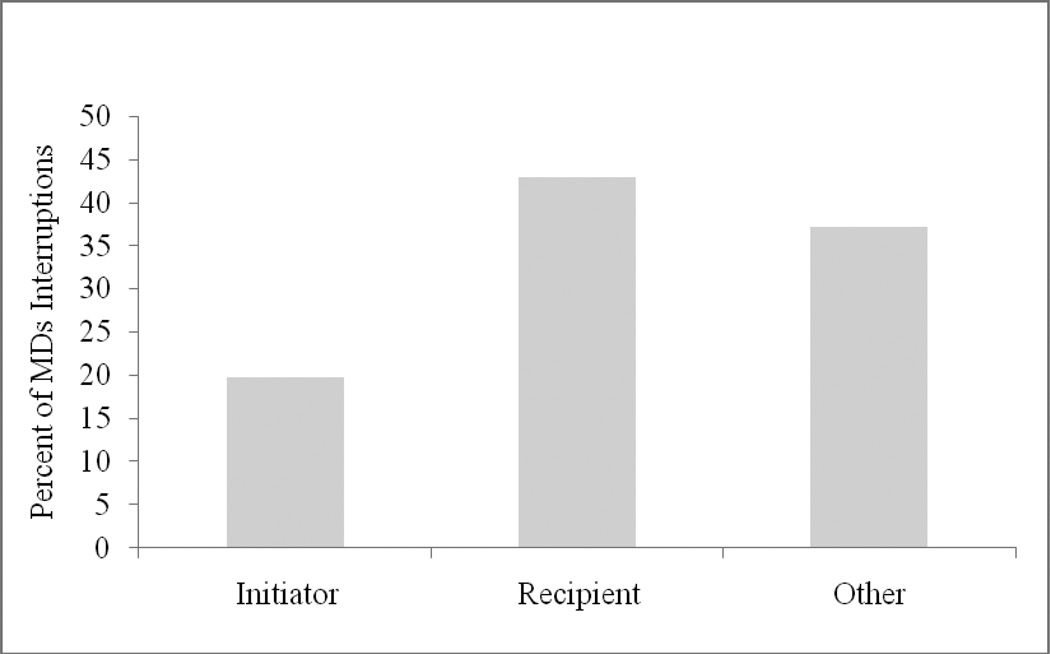

Medical doctors initiated 2.1 interruptions per hour. However, as the recipient of an interruption, MDs were found to have 25.19 percent of all activities interrupted. Consequently, MDs received 10.58 interruptions per hour. As shown in Fig. 2, MDs were more likely to be the recipient of an interruption than initiator.

Fig. 2.

The interruption roles for MDs working in a level one trauma center.

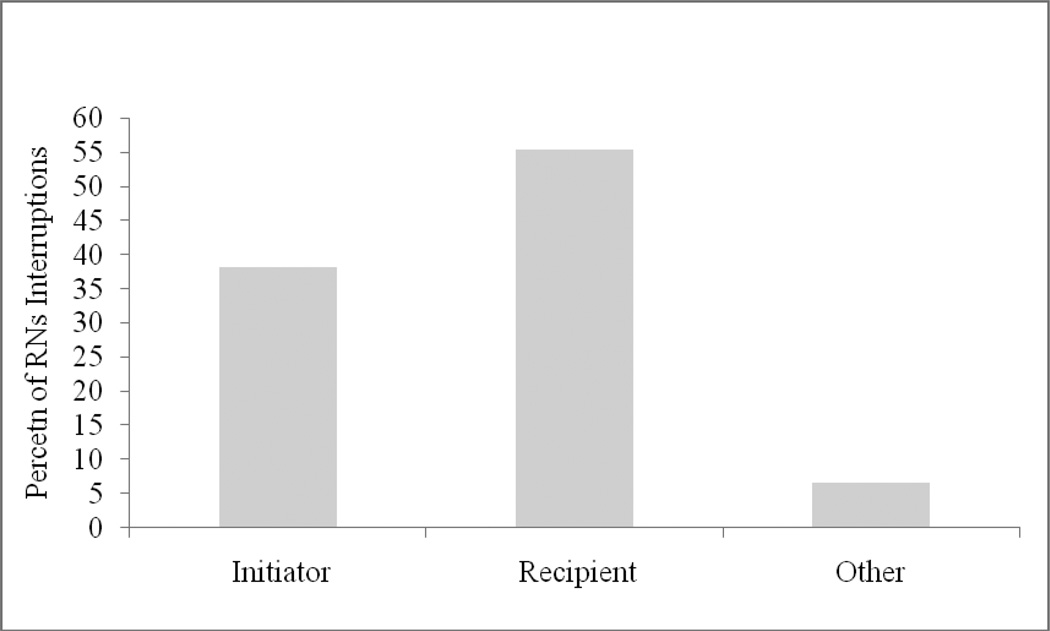

Similarly, RNs were more likely to be the recipient of an interruption rather than the initiator as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The interruption roles for RNs working in a level one trauma center.

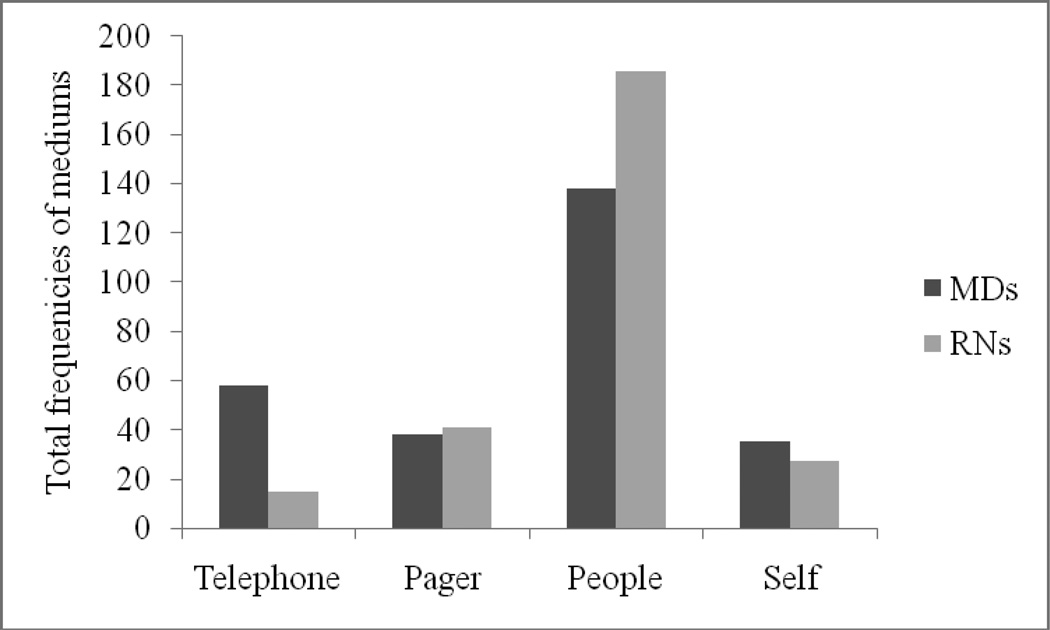

Furthermore, 16.45 percent of all RN activities were interrupted. Registered nurses were interrupted at an average rate of 11.65 interruptions per hour. The RNs initiated 36.16 percent of observed interruptions. When compared to MDs, RNs were more likely to initiate an interruption. This could be attributed to differences in clinical responsibilities. For instance, RNs may initiate an interruption to give report to another nurse when transferring a patient to another unit or when requesting an MD to assess a patient because of a change in condition. Analysis of the notes indicated that MDs and RNs most often used face-to-face encounters to initiate an interruption (Fig. 4). The telephone was also commonly used as a medium to deliver an interruption. Mobile or cellular telephones were used by MDs in addition to traditional landline telephones (POTS). Mobile telephones were not available for use by staff RNs. Consequently, RNs only used POTS to initiate an interruption.

Fig. 4.

Mediums used to interrupt MDs and RNs.

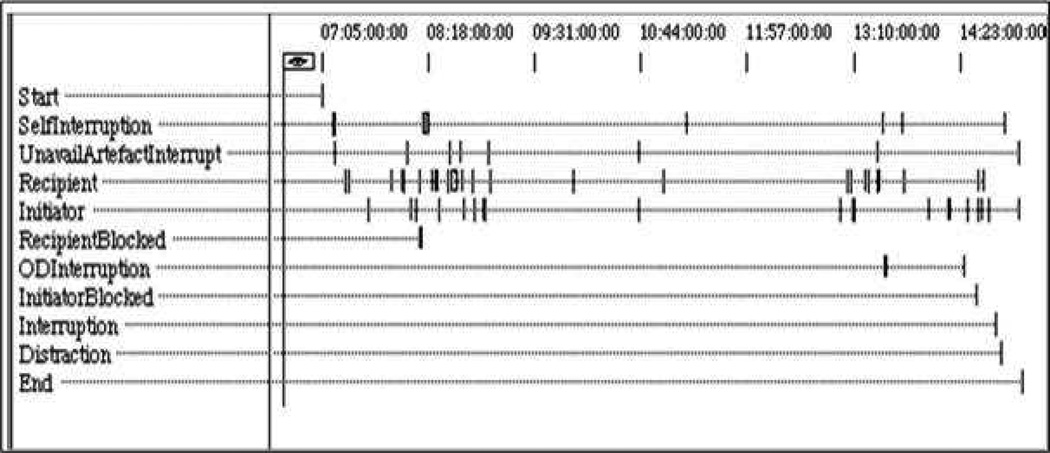

Upon finalization of the taxonomy, the data were analyzed using MacSHAPA© to graphically depict when the study subject engaged in the role of initiator or recipient of an interruption (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

A timeline display for the role of initiator and recipient of interruptions for a single subject.

The timeline indicates the times when the subject was either the initiator or recipient of an interruption. Also, the timeline shows the specific task the initiator used to interrupt another person or when the subject was interrupted. Furthermore, the timeline for each observation graphically reveals how interruptions segment workflow into unequal units resulting in suspended unfinished tasks for the recipient of an interruption. In this study both RNs and MDs resumed tasks more often than leaving them unfinished or forgotten. In a number of observations details, were not sufficient to indicate if the primary interrupted task was unfinished or forgotten. The subject may have considered the task complete at the time of interruption. However, this perception would not be obvious to the observer.

4.0. Discussion

This study identified the interruption roles of initiator and recipient for MDs and RNs from recorded observations in the trauma section of a level one trauma center. Findings from this study indicate that MDs initiated an interruption less often than receiving one. Similarly, RNs took the role as initiator of an interruption less often than that of recipient. Interruptions can also be initiated through environmental conditions such as when supplies or services are not available. Both MDs and RNs most often initiated an interruption through face-to-face interactions. Furthermore, the telephone was identified to be the second most frequently used medium through which to deliver an interruption.

When using synchronous technologies such as the telephone, the initiator needs to know how and when to deliver the interruption to lessen the negative impact on task performance for the recipient. This is an escalating challenge as mobile technologies, such as mobile telephones and personal digital assistants (PDAs) become more common in the ED. The use of mobile telephones has been reported as improving patient safety due to the rapid delivery of information to MDs [25]. However, the study did not report if the delivery of information via a mobile telephone interrupted the recipient’s workflow.

Currently, the recipient of an interruption may have limited choices about how to manage the instant accessibility as some mobile technologies may lack features that would allow one to postpone receiving the interruption as opposed to older technologies, such as pagers and landline telephones. The mobile telephones in this study did not have a voice mail feature that would permit the recipient to delay the interrupting telephone call. Then again messages left in voicemail could result in indefinite deferment in responding to the message. With a pager, the recipient paged did not need to immediately attend to the page message, as it was stored in memory of the devices. For landline telephones, a clerical person is usually designated to answer calls. This person could intercept the interruption by taking a message or possibly provide information to the initiator of the call. In this study, only MDs had mobile telephones while RNs did not. However, as mobile technology comes into widespread use in the clinical setting, there is a greater need to study its impacts on the interruption roles of initiator and recipients.

The initiator of an interruption contributes to an increase in the cognitive load for the recipient because interruptions result in task switching [3]. Empirical research studies have found task switching results in increased time to perform tasks [26–29] as well as an increase in performance errors [30, 31].

In an observational study of office workers, O’Conaill and Frohilch reported that 60 percent of tasks were resumed. However, 40 percent of interrupted tasks were left unfinished [32]. In a similar observational study of office workers, Marks, Gonzales, and Harris reported 77.2 percent of interrupted tasks were resumed while 27.8 percent of interrupted tasks were left unfinished [33]. Findings from this study showed resuming an interrupted task was consistent with results reported by other researchers.

It is recommended that future research studies identify the types and consequences of interruptions caused by technology. It is suggested that the role-based taxonomy presented in this paper be used to classify interruptions in other studies of interruptions. Findings from those studies can then be used to design strategies to mitigate or decrease the negative effects of interruptions with consideration given to the role of initiator as well as recipient.

5.0. Conclusion

A role-based taxonomy of interruptions was derived from the recorded notes using grounded theory. The categories within the taxonomy show that MDs and RNs initiate interruptions as well as receive them.

This study suggests the need to develop strategies to decrease or mitigate the negative effects of interruptions and must consider the interaction between the initiator and the recipient of an interruption. Failure to consider why the interruption was initiated will lead to the formulation of ineffective strategies to manage interruptions. The introduction and use of technology in the clinical setting to manage interruptions must be critically evaluated so that MDs and RNs do not initiate unnecessary interruptions.

What was known before the study

The clinical environment is described as interrupt-driven resulting in an unpredictable workflow.

The recipients of interruptions have been studied extensively.

Few studies have examined the initiators of interruptions.

What is known after the study

MDs and RNs initiated fewer interruptions than they received.

MDs and RNs initiated interruptions most often through face-to-face encounters.

A role-based taxonomy of interruptions has been developed to classify initiators and recipients of interruptions.

Strategies to decrease or mitigate the negative effects of interruptions must consider the interaction between the initiator and the recipient.

Failure to consider why an interruption was initiated will lead to the formulation of ineffective strategies to manage interruptions.

The introduction and use of technology needs to be critically evaluated so that MDs and RNs do not initiate unnecessary interruptions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a training fellowship from the Keck Center for Computational and Structural Biology of the Gulf Coast Consortia (NLM Grant No. 5 T15 LM07093) and Grant R01 LM07894 from the National Library of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brixey JJ, et al. A concept analysis of the phenomenon interruption. Advances in Nursing Science. 2007;30(1):E26–E42. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200701000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coiera E. Clinical communication - A new informatics paradigm; Proc. American Medical Informatics Association Autumn Symposium; 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coiera E, Tombs V. Communication behaviours in a hospital setting: an observational study. BMJ. 1998;316(7132):673–676. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7132.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coiera EW, et al. Communication loads on clinical staff in the emergency department. MJA. 2002;176(9):415–418. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm C, et al. Work interrupted: a comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2001;38(2):146–151. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chisholm CD, et al. Emergency department workplace interruptions: Are emergency physicians "interrupt-driven" And "multitasking"? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1239–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel Event Alert. [cited 2006 November 29];2001 Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. A follow-up review of wrong site surgery. [cited 2006 March 8];Sentinel Event Alert. 2001 Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Preventing ventilatorrelated deaths and injuries. [cited 2006 November 29];Sentinel Event Alert. 2002 Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aspden P, et al., editors. Preventing medication errors. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. p. 287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wears RL. Caution interrupted. [cited 2007 September 12];AHRQ WebM&M [Online journal] 2004 Available from: http://www.webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx?caseID=73&searchStr=interruptions.

- 13.Spencer R, Coiera E, Logan P. Variation in communication loads on clinical staff in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(3):268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez G, Coiera E. Interruptive communication patterns in the intensive care unit ward round. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2005;74:791–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sevdalis N, Healey AN, Vincent CA. Distracting communications in the operating theatre. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2007;13(3):390–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stake RE. Qualitative Case Studies. In: Denzen NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, Inc.; 2005. pp. 443–462. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weijer C. Benefit-sharing and protection for communities in genetic research. Clinical Genetics. 2000;58:367–368. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.580506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicente KJ. Cognitive Work Analysis: Toward safe, Productive, and Healthy Computer-Based Work. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlebaum Associates; 1999. p. 392. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy ME. Methodological triangulation: A vehicle for merging quantitative and qualitative research methods. IMage: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1987;19(3):130–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1987.tb00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.QRS. NVivo 2.0. Australia: Doncaster Victoria; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanderson PM, et al. MacSHAPA. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brixey JJ, et al. Towards a hybrid method to categorize interruptions and activities in healthcare. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2007;76(11–12):812–820. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. New York: Aldine Publishing; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brixey JJ, et al. Interruptions in a level one trauma center: A case study. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2008;77(4):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soto RG, et al. Communication in critical environments: Mobile telephones improve patient care. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:535–541. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000194506.79408.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J. The effects of timing of interruption on human action. La Jolla: Department of Psychology and Institute for Cognitive Science; 1987. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czerwinski M, Horvitz E, Wilhite S. Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI 2004. Vienna, Austria: 2004. A diary of task switching and interruptions. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gopher D, Armony L, Greenshpan Y. Switching tasks and attention policies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2000;129(3):308–309. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.129.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cellier JM, Eyrolle H. Interference between switched tasks. Ergonomics. 1992;35(1):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dismukes K, Young G, Sumwalt R. Cockpit Interruptions and Distractions: Effective Management Requires a Careful Balancing Act. ASRS Directline. 1998;(10):4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffon-Fouco M, Ghertman F. Operational Safety of Nuclear Power Plants. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency; 1984. Recueil de donnees sur les facteurs humains a Electricite de France; pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connaill D, Frohlich D. Timespace in the workplace: Dealing with interruptions. CHI'95 Mosaic of Creativity. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mark G, Gonzalez VM, Harris J. Technology, Community, and Safety. Portland, OR: 2005. No task left behind? Examining the nature of fragmented work. [Google Scholar]