Abstract

The cannabinoid (CB2) receptor type 2 has been proposed to prevent the degeneration of dopamine neurons in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated mice. However, the mechanisms underlying CB2 receptor-mediated neuroprotection in MPTP mice have not been elucidated. The mechanisms underlying CB2 receptor-mediated neuroprotection of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) were evaluated in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease (PD) by immunohistochemical staining (tyrosine hydroxylase, macrophage Ag complex-1, glial fibrillary acidic protein, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and CD3 and CD68), real-time PCR and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled albumin assay. Treatment with the selective CB2 receptor agonist JWH-133 (10 μg kg−1, intraperitoneal (i.p.)) prevented MPTP-induced degeneration of dopamine neurons in the SN and of their fibers in the striatum. This JWH-133-mediated neuroprotection was associated with the suppression of blood–brain barrier (BBB) damage, astroglial MPO expression, infiltration of peripheral immune cells and production of inducible nitric oxide synthase, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by activated microglia. The effects of JWH-133 were mimicked by the non-selective cannabinoid receptor WIN55,212 (10 μg kg−1, i.p.). The observed neuroprotection and inhibition of glial-mediated neurotoxic events were reversed upon treatment with the selective CB2 receptor antagonist AM630, confirming the involvement of the CB2 receptor. Our results suggest that targeting the cannabinoid system may be beneficial for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD, that are associated with glial activation, BBB disruption and peripheral immune cell infiltration.

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by the degeneration of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons.1 Although the specific cause of PD has not yet been established, there is increasing evidence that PD is associated with neuroinflammatory processes, such as oxidative stress and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines induced by glial activation, blood–brain barrier (BBB) damage and infiltration of peripheral immune cells.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

These activated glia-generated inflammatory mediators, including reactive oxygen species (ROS)/reactive nitrogen species (RNS), are produced by astroglial myeloperoxidase (MPO) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the substantia nigra (SN) of PD patients and in the SN of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated mice.7, 8, 9, 10 Proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) are also increased in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of PD patients11, 12 and in the SN of MPTP-treated mice,8, 13 which results in the death of dopamine neurons. Altered BBB permeability and an increased number of infiltrated peripheral immune cells, such as ED1+ and CD3+ cells, were detected in PD patients.14, 15 These factors also contribute to the degeneration of dopamine neurons in the MPTP mouse model of PD.14

The endocannabinoid system consists of cannabinoid receptors, their ligands and enzymes for the synthesis and degradation of cannabinoids.16 The cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2 receptor) is expressed primarily in the immune system.17 Several results have revealed intense CB2 receptor expression in the mouse brain,18, 19 including in microglia,20 astrocytes and some subpopulations of neurons,17 indicating that it has an important role in the brain. The activation of CB2 receptors by WIN55,212-2 (a synthetic CB1/2 agonist) or JWH-133 (a synthetic CB2 receptor agonist) suppressed the production of TNF-α and NO in lipopolysaccharide-21, 22 or beta-amyloid-treated microglia22, 23 in culture. The activation of CB2 receptors by HU210 (a synthetic CB1/2 agonist) suppressed the expression of proinflammatory mediators, such as TNF-a, IL-1β and iNOS, in cultured astrocytes.24 WIN55,212-2 inhibited CXCL12-induced lymphocyte chemotaxis25 in vitro and suppressed the expression of chemokines (MIP-1α and MCP-1) in the ischemic-injured rat brain.26 Moreover, the activation of CB2 receptors by JWH-133 and O-1966 decreased ischemic injury by reducing MPO activity in vivo27 and attenuated BBB damage in traumatic brain injury.28

Under the neuropathological conditions of PD, endocannabinoid levels are increased in the cerebrospinal fluid.29 In MPTP-treated mice, CB2 receptor expression is upregulated in microglia, and this increase has been implicated in the neuroprotection of dopamine neurons through the inhibition of microglial activation.30 However, the mechanisms underlying CB2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model have not been elucidated. Here we show that CB2 receptor activation prevents glial activation, including the activation of ED1+ microglia/macrophages and astroglial MPO expression; BBB disruption; infiltration of peripheral immune cells such as T lymphocytes; and increased expression of various proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, eventually resulting in the rescue of dopamine neurons in the SN and in the MPTP mouse model of PD.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased from the following companies: WIN55,212-2, JWH-133, and AM630 from Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA) and MPTP from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). WIN55,212-2, JWH-133 and AM630 were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and then diluted with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Animals and treatments

The experimental protocol (KHUASP[SE]-10-030) was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyung Hee University. All experiments were conducted with 8- to 10-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (22–24 g; Charles River Breeding Laboratory, Yokohama, Japan) in a room that was maintained at 20–22 °C with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. For the induction of MPTP toxicity, the mice received four intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of MPTP (20 mg kg−1, free base; Sigma), which was dissolved in saline, at 2-h intervals according to a previously reported method.8, 31, 32, 33 For the administration of the non-selective CB receptor agonist WIN55,212-2 and the selective CB2 receptor agonist JWH-133, which were dissolved in a 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide solution,31 the mice received i.p. injections of WIN55,212-2 (10 μg kg−1 body weight once a day) and various doses of JWH-133 (0.1, 1 or 10 μg kg−1 body weight once a day) 2 days before the MPTP injections and at additional specified time periods beginning 12 h after the last MPTP injection and continuing for 8 days. The CB2 receptor antagonist AM630 (20 μg kg−1) was i.p. administered 30 min before the WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 injections. Some mice were injected with vehicle as a control (see Supplementary Figure 1A for experimental design).

Immunohistochemistry

Brain tissue was prepared for immunohistochemical staining as previously described.31 In brief, brain sections were rinsed in PBS and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at room temperature. The following day, the brain sections were rinsed with PBS-0.5% bovine serum albumin, incubated with an appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), and processed with an avidin–biotin complex kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The bound antiserum was visualized by incubating the tissue with 0.05% diaminobenzidine-HCl and 0.003% hydrogen peroxide in 0.1 M PBS. The diaminobenzidine-HCl reaction was stopped by rinsing the tissue in 0.1 M PBS. The primary antibodies included those directed against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, 1:2000; Pel-freez, Brown Deer, WI, USA), macrophage antigen complex-1 (MAC-1, 1:200; Serotec, Oxford, UK), CD68 (clone ED1 CD68 microglial/macrophage marker (ED-1), 1:1000; Serotec), CD3 (T lymphocytes, 1:500; Serotec), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:5000; Neuromics, Edina, MN, USA) and MPO (1:500; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Stained cells were viewed and analyzed under a bright-field microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Stereological cell counting

Unbiased stereological estimates of the total number of TH-i.p. neurons, MPO-i.p. cells, CD3-i.p. cells and ED1-i.p. cells in the SN were made using the optical fractionator method, which was applied to tissue from the various animal groups using an Olympus Computer-Assisted Stereological Toolbox system version 2.1.4 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously31. Actual counting was performed using a × 100 objective. Estimates of the total numbers of cells were calculated according to the optical fractionator equation.34 More than 300 points over all sections of each specimen were analyzed.

Densitometric analyses

As previously described,31 the optical density of TH-positive fibers in the striatum (STR) was examined at × 35 original magnification using the IMAGE PRO PLUS system (Version 4.0; Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA) on a computer that was attached to a light microscope (Zeiss Axioskop, Oberkochen, Germany) interfaced with a CCD video camera (Kodak Mega Plus model 1.4 I; Kodak, New York, NY, USA). To control for variation in background illumination, the average of background density readings from the corpus callosum was subtracted from that of density readings from the STR for each section. Then, the average of all sections of each animal was calculated separately before the data were processed statistically.

Real-time (RT)-PCR for cytokines and chemokines

Animals treated with or without CB receptor agonists and/or the CB2 receptor antagonist were decapitated 48 h after the injection of MPTP, and the bilateral SN regions were immediately isolated. Total RNA was prepared with RNAzol B (Tel-Test, Friendwood, TX, USA) and reverse transcription was carried out using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primer sequences used in this study were as follows: 5′-CTGCTGGTGGTGACAAGCACATTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATGTCATGAGCAAAGGCGCAGAAC-3′ (reverse) for iNOS; 5′-GCGACGTGGAACTGGCAGAAGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGAGAGGGAGGCCATTTGGGAAC-3′ (reverse) for TNF-α 5′-GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT-3′ (reverse) for IL-1β 5′-TTCTCTGTACCATGACACTCTGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGTGGAATCTTCCGGCTGTAG-3′ (reverse) for MIP-1α 5′-TTCCTGCTGTTTCTCTTACACCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGTCTGCCTCTTTTGGTCAG-3′ (reverse) for MIP-1β 5′-TTAAAAACCTGGATCGGAACCAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCATTAGCTTCAGATTTACGGGT-3′ (reverse) for MCP-1; 5′-TTACCAGCACAGGATCAAATGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGGAAGTAGAATCTCACAGCAC-3′ (reverse) for RANTES; 5′-CCAAGTGCTGCCGTCATTTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCTCGCAGGGATGATTTCAA-3′ (reverse) for IP-10; and 5′-GAGCGAAAGCATTTGCCAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCATCGTTTATGGTCGGAA-3′ (reverse) for 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA). RT-PCR reactions were performed in a reaction volume of 10 μl, including 2 μl 1/50-diluted RT product as a template, 5 μl of SYBR Green PCR master mix (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and 10 pmol of each primer described above. The PCR amplifications were performed with 50 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, annealing at 60 °C for 10 s and extension at 72 °C for 20 s using a Light Cycler (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Average threshold cycle (Ct) values for iNOS, IL-1β, TNF-α, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MCP-1, RANTES and IP-10 that were obtained from triplicate PCR reactions were normalized to the average Ct value for 18S rRNA. To express relative amounts, the ΔΔCt value was calculated by subtracting the ΔCt value of the control group from the ΔCt value of each group. The ratios of expression levels were calculated as 2−(mean ΔΔCt).

FITC-labeled albumin assay

A fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled albumin (MW=69–70 kDa, Sigma) assay was performed to visualize BBB leakage. Animals were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (360 mg kg−1, i.p. injection) and killed 3 days after the last MPTP injection. As previously described,33 in all animals, heparin (100 U kg−1 in 10 ml Hank's balanced salt solution) was injected into the common carotid artery following cardiac puncture. Immediately after heparin was injected, 10 ml FITC-linked albumin (5 mg ml−1) was similarly infused at a rate of 1.5 ml min−1. Within 2 min, the brains were removed and immediately immersed into a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (dissolved in 0.1 M PBS) for 1 day; then, the brains were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. The brains were sectioned on a sliding microtome in 30-μm-thick coronal sections. The sections were collected and floated in 0.1 M PBS and mounted on gelatin-subbed glass slides. Sections were dried and coverslipped using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). To quantify the total area of FITC-labeled albumin leakage, three or four images of the SN region were obtained, thresholded using Image J, quantified and normalized by the value obtained in PBS-injected mice.

Statistics

All values are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. Statistical significance (P<0.05 for all analyses) was assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Instat 3.05 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA), followed by Student–Newman–Keuls analyses.

Results

CB2 receptor activation prevents degeneration of dopamine neurons in the SN of MPTP-lesioned mice in vivo

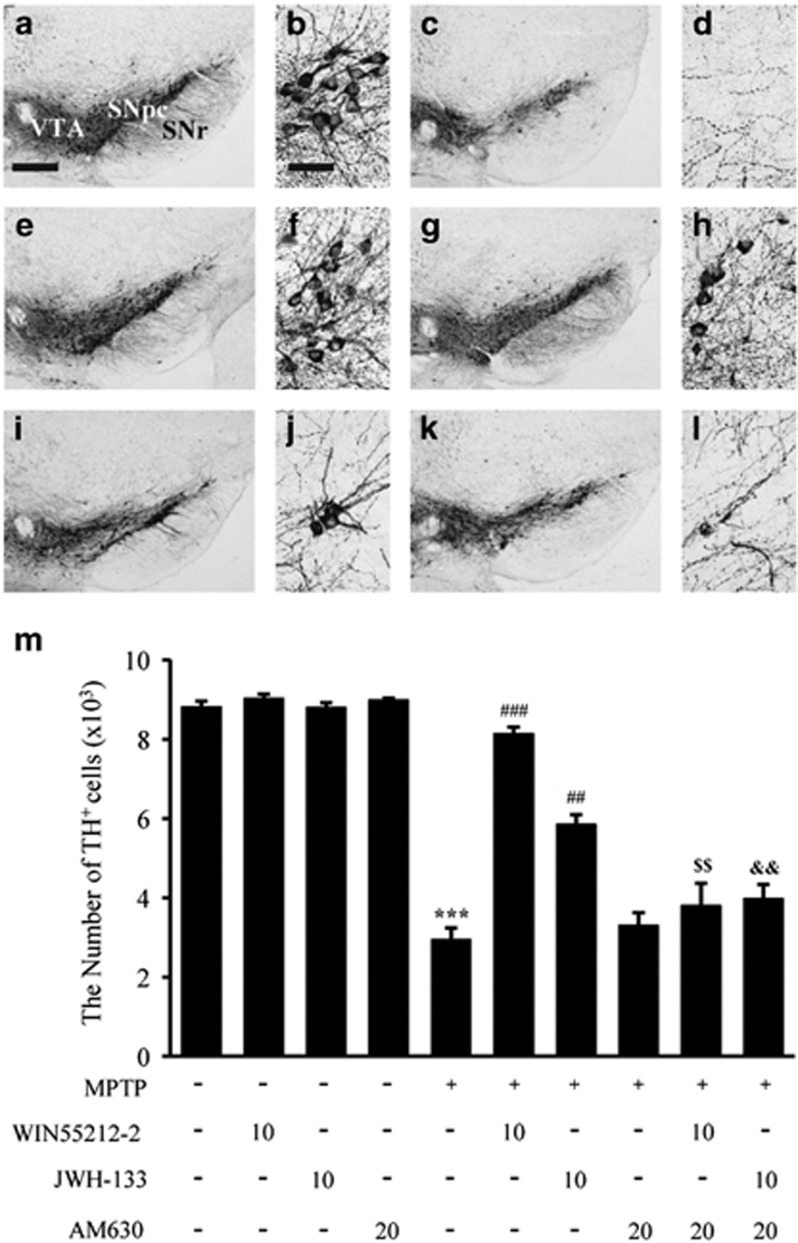

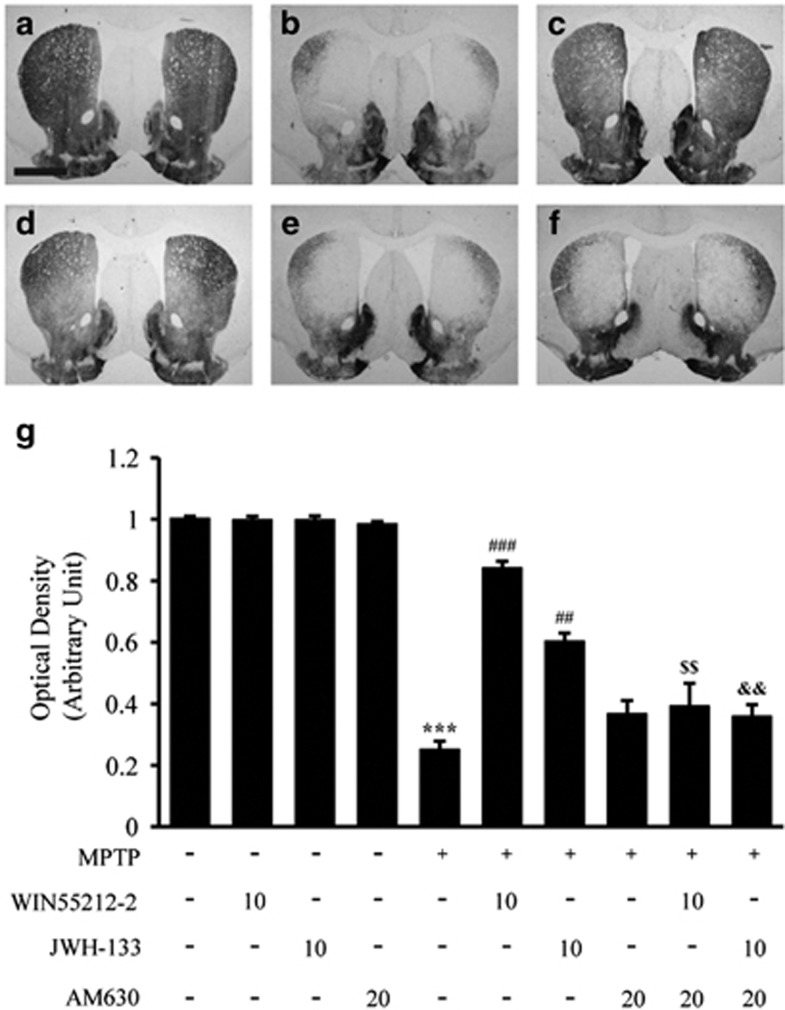

To explore the potential role of the cannabinoid receptor in PD, the mouse MPTP-induced lesion model of PD was used.9, 31 The mice in each group received four i.p. injections of MPTP (20 mg kg−1 body weight) or PBS (control) at 2-h intervals (Supplementary Figure 1A). At 7 days after the last MPTP injection, the brains were removed and sections were immunostained for TH to specifically detect dopamine neurons. Consistent with our recent reports,9, 31 at 7 days, there was a significant loss of TH+ cells in the SN (Figures 1c and d) and of TH+ fibers in the STR (Figure 2b) in the MPTP-injected mice compared with the PBS-treated control mice (Figures 1a and b,2a). By contrast, mice treated with WIN55,212-2 (a CB1/2 receptor agonist) and 10 μg kg−1 body weight JWH-133 (a selective CB2 receptor agonist) exhibited significantly attenuated loss of TH+ cells in the SN (Figures 1e–h) and of TH+ fibers in the STR (Figures 2c and d). As assessed by stereology in the SN, WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 increased the number of TH+ cells by 68% and 36%, respectively, compared to treatment with MPTP only (Figure 1m). WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 also increased the density of TH+ fibers in the STR by 65% and 38%, respectively, compared to treatment with MPTP only (Figure 2g). Treatment with 0.1 or 1 μg kg−1 JWH-133 did not affect the number of TH+ cells in the SN or the density of TH+ fibers in the STR (Supplementary Table 1). It seems noteworthy that pre-treatment with WIN55,212-2 did not alter conversion of MPTP to MPP+,31 although WIN55,212-2 is known to affect the dopamine transporter.30

Figure 1.

The CB2 receptor protects nigral dopamine neurons from MPTP neurotoxicity in vivo. Animals that received PBS as a control (a, b); MPTP (c, d); MPTP and WIN55,212-2 (e, f); MPTP and JWH-133 (g, h); MPTP, WIN55,212-2 and AM630 (i, j); or MPTP, JWH-133 and AM630 (k, l) were killed 7 days after the last MPTP injection. Brain tissues were cut, and SN tissues were immunostained with an antibody to TH to label dopamine neurons. (b, d, f, h, j and l) higher magnifications of (a, c, e, g, i and k), respectively. (m) The numbers of TH+ neurons in the SN were counted. Five to seven animals were used for each experimental group. *P<0.001 significantly different from controls. ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 significantly different from MPTP. $$P<0.01 significantly different from MPTP and WIN55,212-2; and &&P<0.01 significantly different from MPTP and JWH-133 (ANOVA and Student–Neuman–Keuls analysis). SNpc, substantia nigra pars compacta; SNr, substantia nigra pars reticulata; VTA, ventral tegmental area; Scale bars: a, c, e, g, i and k, 300 μm; b, d, f, h, j and l, 50 μm.

Figure 2.

The CB2 receptor protects striatal dopamine fibers from MPTP neurotoxicity in vivo. The STR tissues obtained from the same animals used in Figure 1 were immunostained with a TH antibody to label dopamine fibers. Control (a); MPTP (b); MPTP and WIN55,212-2 (c); MPTP and JWH-133 (d); MPTP, WIN55,212-2 and AM630 (e); and MPTP, JWH-133 and AM630 (f). (g) The optical density of TH+ fibers in the STR. ***P<0.001 significantly different from controls. ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 significantly different from MPTP. $$P<0.01 significantly different from MPTP and WIN55,212-2; and &&P<0.01 significantly different from MPTP and JWH-133 (ANOVA and Student–Neuman–Keuls analysis). Scale bars: a–f, 500 μm.

To determine whether the observed neuroprotective effects were associated with activation of CB2 receptors, we selectively inhibited CB2 receptor function with the CB2 receptor antagonist AM630. In the SN of the MPTP-lesioned mice, AM630 dramatically inhibited the neuroprotective effects of WIN55,212-2 (Figures 1i and j) and JWH-133 (Figures 1k and l). As assessed by stereology, the number of TH+ cells in the SN and in the MPTP+WIN55,212-2+AM630- and MPTP+JWH-133+AM630-treated mice was reduced by 43% (P<0.01) and 32% (P<0.01), respectively, compared with the numbers in the MPTP+WIN55,212-2- and MPTP+JWH-133-treated mice (Figure 1m). AM630 also reduced the number of TH+ fibers in the STR by 48% and 30% in the MPTP+WIN55,212-2+AM630- and MPTP+JWH-133+AM630-treated mice (Figures 2e and f), respectively, compared with the numbers in the corresponding control mice (Figure 2g). The number of TH+ cells in the SN and the density of TH+ fibers in the STR in the AM630-treated MPTP-lesioned mice were similar to those in the MPTP-lesioned mice.

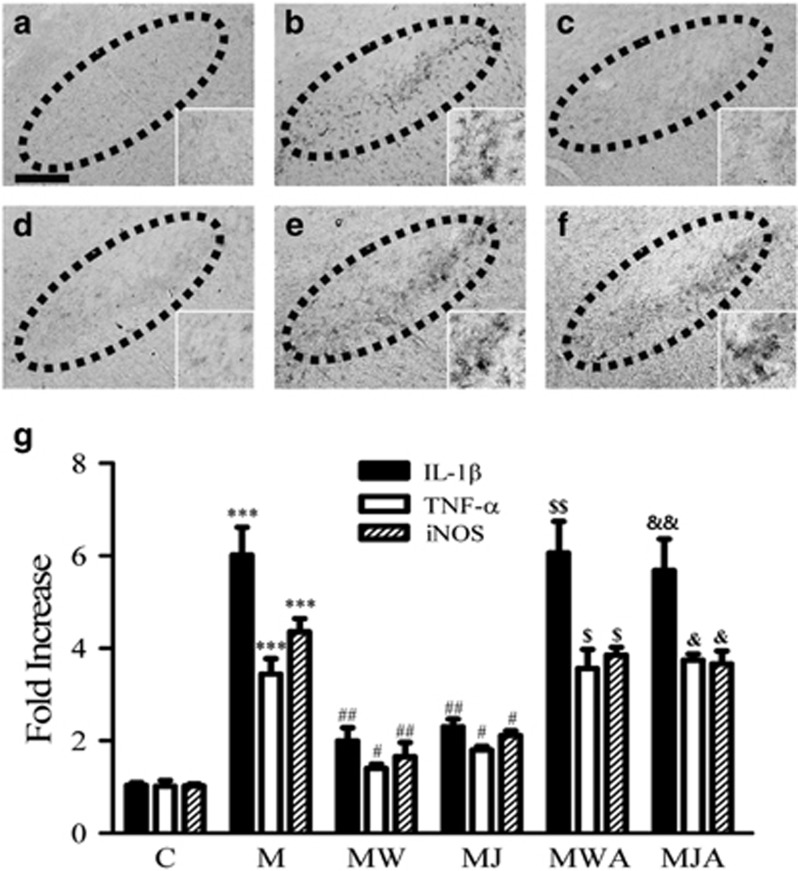

CB2 receptors prevent microglial activation and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the SN of MPTP-lesioned mice in vivo

Accumulating evidence suggests that activated microglia have a critical role in the degeneration of dopamine neurons in the MPTP model.3 Thus, we next examined whether the neuroprotection mediated by CB2 receptor activation was due to the inhibition of MPTP-induced microglial activation in the SN in vivo. Three days after the final MPTP treatment, SN sections were processed for immunostaining with a MAC-1 antibody to detect microglial activation. Consistent with previous studies, including ours,8, 31, 32 numerous MAC-1+ activated microglia, which exhibited larger cell bodies and thick processes, were observed in the MPTP-treated SN (Figure 3b), whereas such cells were largely absent from the PBS-treated control SN (Figure 3a). Treatment with WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 mitigated these effects of MPTP and dramatically decreased the number of activated microglia in the MPTP-treated SN (Figures 3c and d). The blockade of microglial activation was reversed by AM630, the CB2 receptor antagonist (Figures 3e and f). WIN55,212-2, JWH-133 and AM630 alone had no effect on microglial activation (data not shown).

Figure 3.

The CB2 receptor inhibits microglial activation and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the SN in vivo. Animals that received vehicle as a control (a); MPTP (b); MPTP and WIN55,212-2 (c); MPTP and JWH-133 (d); MPTP, WIN55,212-2 and AM630 (e); or MPTP, JWH-133 and AM630 (f) were killed 3 days after the last MPTP injection. Brain tissues were cut, and SN tissues were immunostained with an antibody for MAC-1 to label microglia (a–f). Insets show higher magnifications of a–f. Dotted lines indicate the SNpc. Scale bars: a–f, 200 μm. (g) Real-time PCR showing mRNA expression of proinflammatory mediators in the SN. Total RNA was isolated from the bilateral SN for real-time PCR 1 day after treatment with vehicle as a control (C); MPTP only (M); MPTP and WIN55,212-2 (MW); MPTP and JWH-133 (MJ); MPTP, WIN55,212-2 and AM630 (MWA); or MPTP, JWH-133 and AM630 (MJA). The CB2 receptor dramatically attenuated MPTP-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α and iNOS. The results represent the mean±s.e.m. of three to four separate experiments. ***P<0.001 significantly different from C. #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01, significantly different from M. $P<0.05 and $$P<0.01 significantly different from MW. &P<0.05 and &&P<0.01 significantly different from MJ (ANOVA and Student–Neuman–Keuls analysis).

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that in the MPTP mouse model, activated microglia can produce neurotoxic proinflammatory molecules, including IL-1β, TNF-α and iNOS.8, 10 Thus, we determined whether CB2 receptor activation affected MPTP-induced expression of IL-1β, TNF-α and iNOS in the SN in vivo, resulting in dopamine neuron survival. The results of RT-PCR showed that MPTP-induced transient expression of IL-1β, TNF-α and iNOS (P<0.001) in the SN 24 h after the last MPTP injection. By contrast, treatment with WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 reduced the expression of IL-1β by 66% and 62% (P<0.01), of TNF-α by 61% and 56% (P<0.05) and of iNOS by 69% (P<0.0) and 65% (P<0.05; Figure 3g), respectively, in the MPTP-treated SN. These inhibitory effects of WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 were almost completely reversed by AM630 (Figure 3g). As a control, AM630 alone had no effects. These results further verified that MPTP-induced microglial activation and expression of proinflammatory molecules could be regulated by CB2 receptor activation.

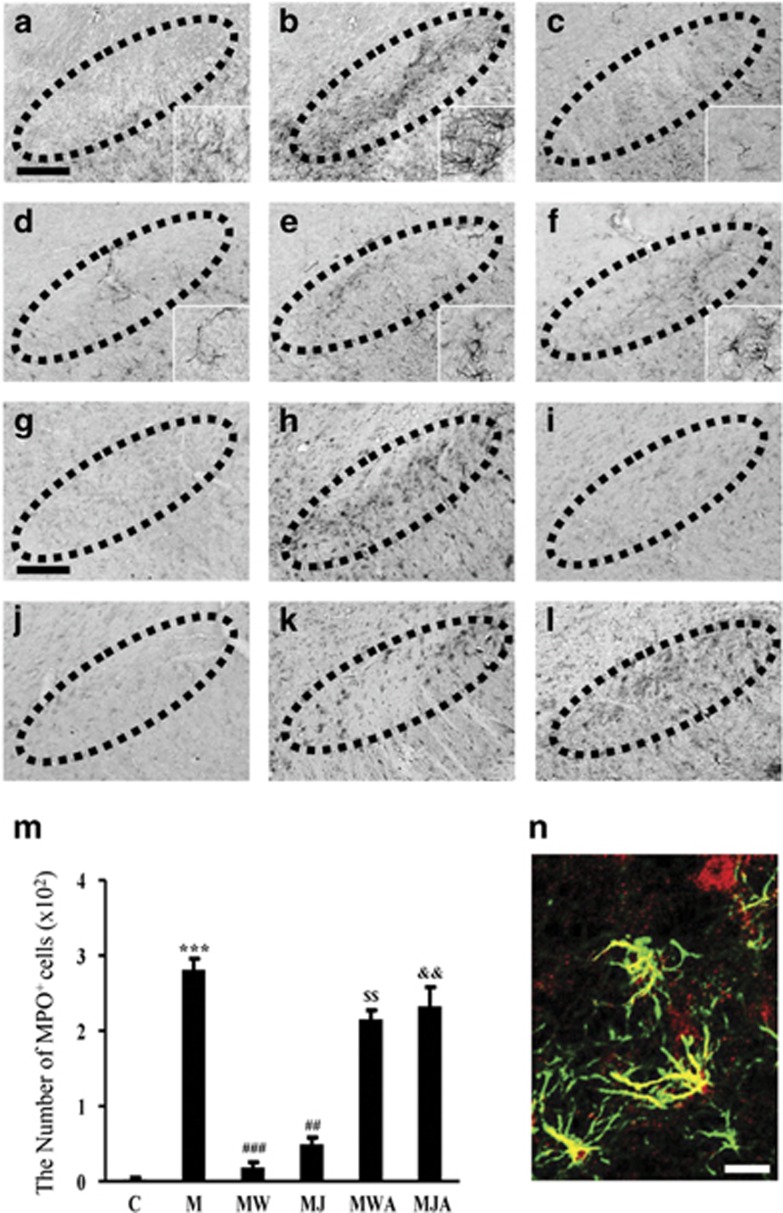

CB2 receptors inhibit astrocytic MPO expression in the SN of MPTP-lesioned mice in vivo

Similar to our previous results,8, 9 GFAP immunostaining of tissues adjacent to those used for MAC-1 immunostaining showed that resting astrocytes (which have small somas with thin dendrites; inset in Figure 4a) were transformed into active astrocytes (which have enlarged cell bodies with short or thick processes; inset in Figure 4b). Treatment with WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 inhibited astroglial activation in the MPTP-treated SN (Figures 4c and d), respectively. These inhibitory effects were reversed by AM630 (Figures 4e and f). Each compound alone had no effect (data not shown).

Figure 4.

The CB2 receptor attenuates MPTP-induced astroglial activation and expression of myeloperoxidase (MPO) in the SN in vivo. The SN tissues obtained from the same animals used in Figure 3 were immunostained with a GFAP antibody to label astrocytes (a–f) and with an MPO antibody to evaluate MPO immunoreactivity (g–l). Animals that received PBS as a control (a, g); MPTP (b, h); MPTP and WIN55,212-2 (c, i); MPTP and JWH-133 (d, j); MPTP, WIN55,212-2 and AM630 (e, k); or MPTP, JWH-133 and AM630 (f, l) were killed 3 days after the last MPTP injection. Insets show higher magnifications of a–l. Dotted lines indicate the SNpc. (m) The number of MPO-positive cells in the SN was counted. Four to five animals were used for each experimental group. C, control; M, MPTP; MW, MPTP and WIN55,212-2; MJ, MPTP and JWH-133; MWA, MPTP and WIN55,212-2 and AM630; MJA, MPTP and JWH-133 and AM630. ***P<0.001 significantly different from controls; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 significantly different from MPTP only; $$P<0.01, significantly different from MW. &&P<0.01 significantly different from MJ (ANOVA and Student–Neuman–Keuls analysis). (n) Localization of MPO immunoreactivity in GFAP+ activated astrocytes in the MPTP-treated SN. The SN tissues obtained from the same animals used in b were simultaneously immunostained with antibodies against MPO and GFAP, as a marker for astrocytes. Scale bars: a–l, 200 μm.

Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that MPO is upregulated in astrocytes in the SN of PD patients and MPTP-treated mice.8, 9 Mice deficient in MPO are resistant to MPTP neurotoxicity.7 Accordingly, we examined whether WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 could rescue nigral dopamine neurons by inhibiting MPO expression. Compared with the PBS-treated mice (Figure 4g), the MPTP-treated mice showed a profound increase in the number of MPO+ cells in the SN (Figure 4h). This increase was dramatically attenuated by WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 (Figures 4i and j), respectively. This inhibition was reversed by AM630 (Figures 4k and l for WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133, respectively). Quantification of the number of MPO+ cells in the SN by stereological cell counts confirmed these results, showing that the number of MPO+ cells was 287-fold higher in the MPTP-treated SN than in the SN of PBS-treated controls (P<0.001, Figure 4m). Treatment with WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 reduced the number of MPO+ cells in the MPTP-treated SN by 88% (P<0.01; Figure 4m) and 65% (P<0.001; Figure 4m), respectively. The decrease in the number of MPO+ cells was completely abolished by AM630 (P<0.01; Figure 4m). Consistent with our previous data, additional double-immunofluorescence staining confirmed localization of MPO within astrocytes 3 days post-MPTP injection (Figure 4n).

CB2 receptors inhibit MPTP-induced BBB leakage in the SN in vivo

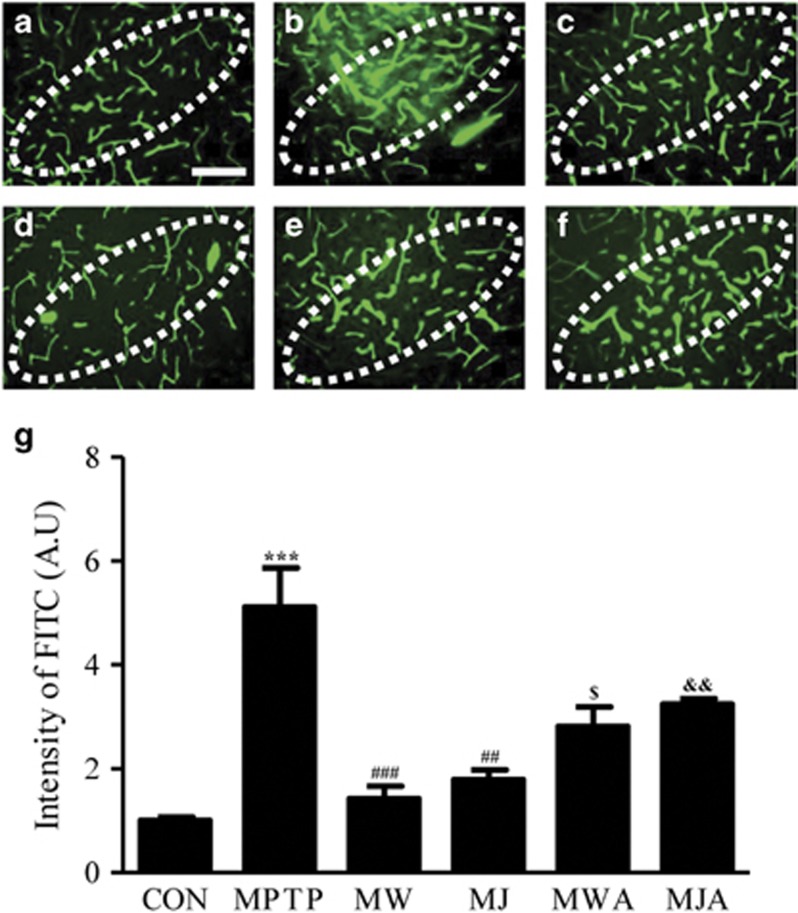

Several clinical and experimental results have shown increased BBB permeability in PD patients35, 36 and MPTP-treated mice,33, 37, 38 and this effect could be involved in the degeneration of dopamine neurons and the activation of glia in the SN. Thus, we examined the effects of WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 on MPTP-induced BBB disruption by detecting FITC-labeled albumin in the brain 3 days after the last MPTP injection. Substantial increases in FITC-labeled albumin levels were evident in the MPTP-treated SN (P<0.001; Figures 5b and g) compared with the SN of the PBS-treated controls (Figures 5a and g). This MPTP-induced increase in FITC-labeled albumin levels in the SN was attenuated by treatment with WIN55,212-2 (P<0.01; Figures 5c and g) and JWH-133 (P<0.001; Figures 5d and g). This inhibition was reversed by AM630 (Figures 5e, f and g), whereas each compound alone had no effect (data not shown).

Figure 5.

The CB2 receptor prevents MPTP-induced BBB disruption in the SN in vivo. At 3 days after the injection of vehicle as a control or of MPTP in the absence or presence of WIN55,212-2, JWH-133 and/or AM630, FITC-labeled albumin was administered to detect brain vascular permeability. Control (a); MPTP (b); MPTP and WIN55,212-2 (c); MPTP and JWH-133 (d); MPTP, WIN55,212-2 and AM630 (e); and MPTP, JWH-133 and AM630 (f). Dotted lines indicate the SNpc. Scale bars: a–l, 100 μm. (g) Bars represent the FITC-labeled-albumin-positive area in the SNpc. Four or five animals were used for each experimental group. Actual values are normalized by the value for the PBS-injected control. CON, control; M, MPTP; MW, MPTP and WIN55,212-2; MJ, MPTP and JWH-133; MWA, MPTP and WIN55,212-2 and AM630; MJA, MPTP and JWH-133 and AM630. ***P<0.001 significantly different from controls; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 significantly different from MPTP only; $P<0.05 significantly different from MW; and &&P<0.01 significantly different from MJ (ANOVA and Student–Neuman–Keuls analysis).

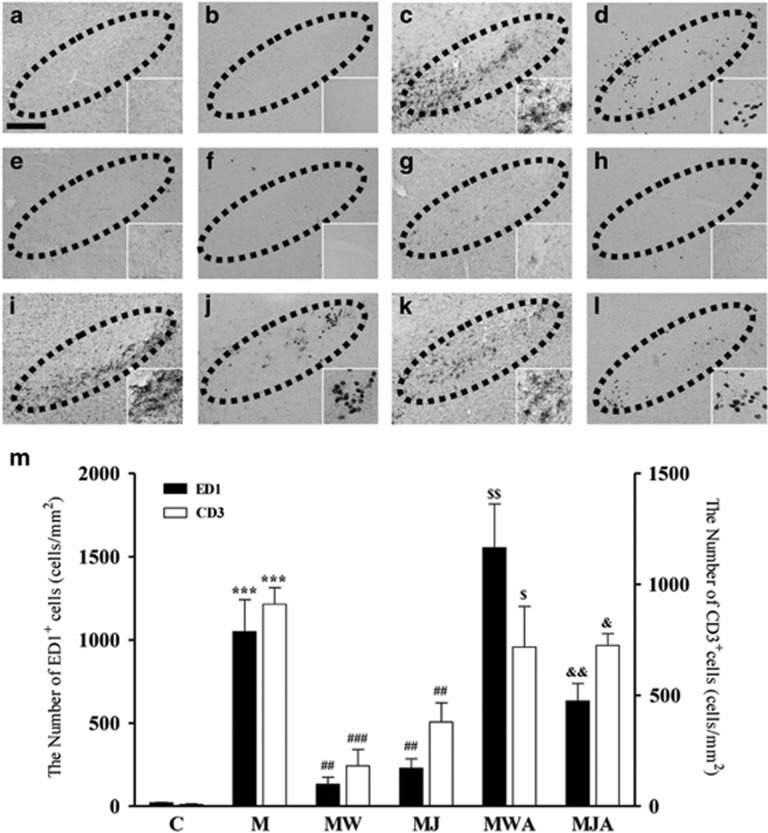

CB2 receptors inhibit MPTP-induced infiltration of peripheral immune cells in the SN in vivo

The infiltration of peripheral macrophages and lymphocytes into the brain has been observed in PD patients,2, 39 and mice deficient in CD4 are resistant to MPTP-induced neurotoxicity.14 Thus, we investigated whether CB2 receptor function affects MPTP-induced infiltration of peripheral immune cells in the SN. To measure the extent of immune cell infiltration, SN tissue was immunostained with ED1 or CD3 antibodies 3 days after the last MPTP injection, which was administered in the absence or presence of CB receptor agonists and antagonists (Figure 6). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed the infiltration of numerous ED1+ microglia/macrophages (Figure 6c) and CD3+ T cells (Figure 6d) in the SN 3 days after the MPTP injection compared with the numbers of these cells in the corresponding PBS-treated control SN (Figures 6a and b). Treatment with WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 markedly inhibited the MPTP-induced infiltration of peripheral immune cells (Figures 6e–h), respectively. This decreased infiltration of peripheral immune cells was reversed by AM630 (Figures 6i–l). Stereological cell counting showed that the numbers of ED1+ or CD3+ cells in the MPTP-treated SN were 1107- or 887-fold higher, respectively, than those in the PBS-treated control SN (P<0.001; Figure 6m). Treatment with WIN55,212-2 reduced the number of MPTP-induced ED1+ or CD3+ cells in the SN by 93% (P<0.001) and 84% (P<0.01), respectively (Figure 6m). Similar to WIN55,212-2, JWH-133 also decreased the number of ED1+ or CD3+ cells in the SN by 81% and 72%, respectively (P<0.01; Figure 6m). This inhibition was reversed by AM630 (P<0.05, P<0.01; Figure 6m).

Figure 6.

The CB2 receptor inhibits MPTP-induced infiltration of peripheral immune cells in the SN in vivo. The SN tissues obtained from the same animals used in Figure 5 were immunostained with an ED1 antibody to label phagocytotic macrophages and microglia (a, c, e, g, i, and k) and with a CD3 antibody to label T cells (b, d, f, h, j, and l). Animals that received PBS as a control (a, b); MPTP (c, d); MPTP and WIN55,212-2 (e, f); MPTP and JWH-133 (g, h); MPTP, WIN55,212-2 and AM630 (i, j); or MPTP, JWH-133 and AM630 (k, l) were killed 3 days after the last MPTP injection. Insets show higher magnifications of a–l. Dotted lines indicate the SNpc. Scale bars: a–l, 200 μm. (m) The number of CD3+ (white bars) or ED1+ (black bars) cells in the SN were counted. Four to five animals were used for each experimental group. C, control; M, MPTP; MW, MPTP and WIN55,212-2; MJ, MPTP and JWH-133; MWA, MPTP and WIN55,212-2 and AM630; MJA, MPTP and JWH-133 and AM630. ***P<0.01 significantly different from controls; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 significantly different from MPTP only; $P<0.05 and $$P<0.01 significantly different from MW; &P<0.05 and &&P<0.01 significantly different from MJ (ANOVA and Student–Neuman–Keuls analysis).

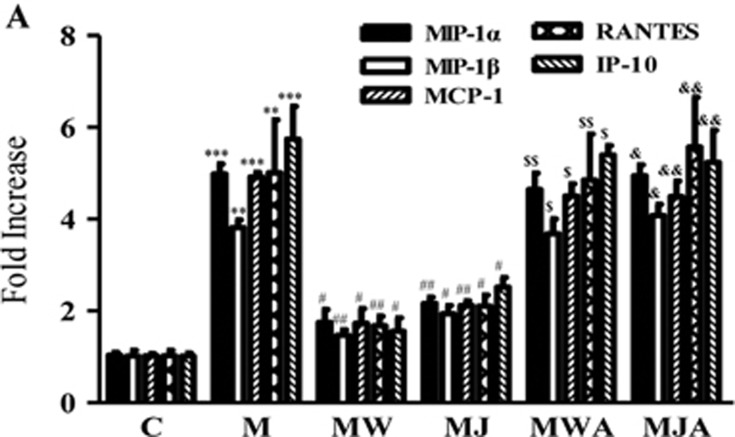

CB2 receptors inhibit MPTP-induced chemokines expression in the SN in vivo

Several reports have shown the elevation of various chemokines in PD patients and the MPTP model,40, 41 and this elevation might be involved in the degeneration of dopamine neurons in the SN.42 Accordingly, we investigated whether CB2 receptor function affected the MPTP-induced expression of various chemokines, including MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MCP-1, IP-10 and RANTES in the SN. At 48 h after the last MPTP injection, which was administered in the absence or presence of CB receptor agonists and a CB2 receptor antagonist, SN tissues were dissected and processed for RT-PCR analysis. The results of RT-PCR showed that MPTP alone significantly increased the expression of various chemokines in the SN (Figure 7). Treatment with WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 attenuated the MPTP-induced increase in the mRNA expression of MIP-1α by 62% and 56%, of MIP-1β by 58% and 55%, of MCP-1 by 61% and 56%, of IP-10 by 61% and 55% and of RANTES by 66% and 54%, respectively, in the SN (Figure 7a). This inhibition was reversed by AM630 (Figures 7a and b)

Figure 7.

The CB2 receptor inhibits MPTP-induced expression of chemokines in the SN in vivo. (a) Real-time PCR showing mRNA expression of chemokines in the SN. Animals that received vehicle or MPTP in the absence or presence of WIN55,212-2, JWH-133 and/or AM630 were killed 2 days later for RT-PCR analysis. The CB2 receptor dramatically reduced the MPTP-induced expression of chemokines, including MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MCP-1, RANTES and IP-10. Graphic representation of the mean±s.e.m. of three to four samples. C, control; M, MPTP; MW, MPTP and WIN55,212-2; MJ, MPTP and JWH-133; MWA, MPTP and WIN55,212-2 and AM630; MJA, MPTP and JWH-133 and AM630. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 significantly different from C. #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 significantly different from M. $P<0.01 and $$P<0.05 significantly different from MW. &P<0.05 and &&P<0.01 significantly different from MJ (ANOVA and Student–Neuman–Keuls analysis).

Discussion

Our results show that WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 rescued nigrostriatal dopamine neurons from MPTP neurotoxicity via CB2 receptor activation in vivo. Although the involvement of both CB1 and CB2 receptors in the beneficial effects of cannabinoids in the MPTP mouse model of PD remains controversial, our pharmacological studies carefully suggest that CB2 receptor activation inhibits neuroinflammatory processes, BBB damage and T-cell infiltration, and prevents nigrostriatal dopamine neuronal death in the MPTP mouse model of PD.

Microglial activation is one of the major contributors to neuroinflammation and has been implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of PD.3, 4, 43 Activated microglia can release harmful substances such as proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) and iNOS-derived ROS and RNS, which subsequently cause the degeneration of dopamine neurons in the SN of human patients with PD and in the MPTP mouse model of PD.4, 43, 44 We recently showed that the number of CD-11b+ and Iba-1+-activated microglia was correlated with ED-1+ microglia/macrophage phagocytic activity in the SN of MPTP-treated mice.9, 33 The increase in the number of ED1+ microglia/macrophage was linearly correlated with dopamine neuronal death in the SN of the MPTP-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 2A). The present data show that MPTP significantly increased the number of ED-1+ activated microglia/macrophages in the SN as well as the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α). By contrast, WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 attenuated the number of ED-1+ cells and the expression of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α in the MPTP-treated mice, although these effects were reversed by the CB2 receptor antagonist AM630. Therefore, it is likely that the CB2 receptor has the capacity to prevent microglial activation and to attenuate the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines, which results in the survival of dopamine neurons in the SN of MPTP-treated mice. This is supported by findings that the neuroprotective effect of WIN55,212-2 on dopamine neurons in MPTP-treated mice is afforded by CB2 receptor-mediated suppression of microglial activation.30

Recent studies have highlighted the presence of infiltrating T cells (CD4+ and CD8+ cells) in the SN of PD patients and MPTP-treated mice.14, 45 The infiltration of T cells (CD4+ and CD8+ cells) may be involved in nigrostriatal dopamine neuron death. Brochard et al. showed CD4+ cell-mediated but not CD8+ cell-mediated degeneration of dopamine neurons in MPTP-treated mice.14, 45 Depboylu et al. showed that infiltrating CD3+ T lymphocytes, which include both CD4+ and CD8+ cells, could regulate the adaptive immune system through crosstalk with microglia and/or macrophages in the SN of MPTP-treated mice.14, 45 The present data showed that MPTP increased the number of infiltrating CD3+ T cells in the SN of the MPTP-treated mice. By contrast, WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 significantly reduced the infiltration of CD3+ T cells into the SN of the MPTP-treated mice. These effects were reversed by the CB2 receptor antagonist AM630, suggesting that CB2 receptor activity inhibits T-cell infiltration and contributes to the survival of dopamine neurons in the SN and in the MPTP mouse model of PD. This hypothesis is supported by our observation that the increase in the number of CD3+ cells was well correlated with the extent of dopamine neuronal death in the SN of the MPTP-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 2A).

Several reports have shown that various chemokines are elevated in PD patients and in the MPTP mouse model of PD.40, 41, 42 An increase in chemokines levels is considered a causative factor of the neurodegeneration associated with the infiltration of peripheral immune cells that is observed in PD,40 although the neurotoxic effects of chemokines in PD patients and MPTP models of PD are not well defined. The present data demonstrated upregulation of chemokines in the SN of the MPTP-treated mice. This increase was inhibited by treatment with WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133, and the effects of WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 were reversed by the CB2 receptor antagonist AM630. These data support the hypothesis that the observed neuroprotective effects of CB2 receptor function are associated with its ability to inhibit the expression of various chemokines in MPTP-treated mice.

Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cells in the mammalian brain and can have both beneficial and detrimental roles in PD.46, 47, 48 There is accumulating evidence that, in MPTP-treated mice, astroglial activation can contribute to the degeneration of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons via the generation of neurotoxic mediators.49, 50 One such mediator that is expressed in activated astrocytes is MPO, which is the key enzyme involved in the generation of cytotoxic ROS/RNS.51, 52 MPO is upregulated in activated astrocytes in the ventral midbrain of human patients with PD and in MPTP mice, and in MPO-deficient mice, nigrostriatal dopamine neurons are resistant to MPTP-induced neurotoxicity.7 Our recent reports showed that pharmacological inhibition of MPO protects dopamine neurons from MPTP-induced neurotoxicity.8, 9 These findings are consistent with our present data, which showed that MPO expression in activated astrocytes was increased in the MPTP-treated SN, as determined by double-labeling immunostaining. Additional experiments showed that JWH-133 and WIN55,212-2 reduced the intensity of GFAP+ labeling in astrocytes and the number of MPO+ cells in the MPTP-treated SN in vivo. These effects were reversed by the CB2 receptor antagonist, suggesting that inhibition of astroglial MPO expression contributes to the neuroprotection mediated by the CB2 receptor. However, these results may be irrelevant due to a previous finding of the lack of an inhibitory effect of WIN55,212-2 on astroglial activation in MPTP-treated mice.30 This apparent discrepancy between the results of the two studies is probably due to the different doses (10 μg kg−1 versus 4 mg kg−1) and/or different time points (before versus after MPTP lesion) used in each study.

The BBB restricts the entry of plasma components, blood cells and leukocytes into the brain and maintains a constant brain environment. Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that glial activation-derived proinflammatory molecules exert harmful effects on BBB integrity in MPTP mouse models of PD.38, 53 Considering the protective and supportive role of the BBB on the microenvironment of the brain and the correlation between BBB disruption and dopamine neuron death,54 it has been hypothesized that BBB dysfunction may account for the degeneration of dopamine neurons in the SN of PD patients35, 36, 55 and in the SN of animal models of PD.4, 38, 53 We recently demonstrated that BBB leakage contributes to the degeneration of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons in the SN of MPTP-treated mice.4, 33 The present data showed that WIN55,212-2 and JWH-133 attenuated the infiltration of FITC-labeled albumin from blood vessels into the SN in the MPTP-treated mice. This effect was reversed by the CB2 receptor antagonist AM630, suggesting that CB2 receptor function attenuates MPTP-induced damage to the BBB and prevents the degeneration of dopamine neurons in the SN of MPTP-treated mice.

In summary, we demonstrated that activation of the CB2 receptor inhibits BBB damage, the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in activated microglia, the infiltration of T cells and astroglial expression of MPO, resulting in the survival of dopamine neurons in vivo in the MPTP mouse model of PD. Therefore, it is likely that targeting the CB2 receptor may have therapeutic value in the treatment of aspects of PD related to neuroinflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2008-0061888).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Experimental & Molecular Medicine website (http://www.nature.com/emm)

Supplementary Material

References

- Savitt JM, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: molecules to medicine. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 1744–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel SH. CD4+ T cells mediate cytotoxicity in neurodegenerative diseases. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 13–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007; 8: 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YC, Ko HW, Bok E, Park ES, Huh SH, Nam JH et al. The role of neuroinflammation on the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. BMB Rep 2010; 43: 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang O. Role of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurobiol 2013; 22: 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N, Miller F, Cazaubon S, Couraud PO. The blood-brain barrier in brain homeostasis and neurological diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1788: 842–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DK, Pennathur S, Perier C, Tieu K, Teismann P, Wu DC et al. Ablation of the inflammatory enzyme myeloperoxidase mitigates features of Parkinson's disease in mice. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 6594–6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YC, Kim SR, Jin BK. Paroxetine prevents loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting brain inflammation and oxidative stress in an experimental model of Parkinson's disease. J Immunol 2010; 185: 1230–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh SH, Chung YC, Piao Y, Jin MY, Son HJ, Yoon NS et al. Ethyl pyruvate rescues nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons by regulating glial activation in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. J Immunol 2011; 187: 960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberatore GT, Jackson-Lewis V, Vukosavic S, Mandir AS, Vila M, McAuliffe WG et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase stimulates dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model of Parkinson disease. Nat Med 1999; 5: 1403–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi M, Harada M, Kondo T, Riederer P, Inagaki H, Minami M et al. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6, epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha are elevated in the brain from parkinsonian patients. Neurosci Lett 1994; 180: 147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T, Sawada M. Biochemistry of postmortem brains in Parkinson's disease: historical overview and future prospects. J Neural Transm Suppl 2007; 72: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DC, Jackson-Lewis V, Vila M, Tieu K, Teismann P, Vadseth C et al. Blockade of microglial activation is neuroprotective in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson disease. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 1763–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochard V, Combadiere B, Prigent A, Laouar Y, Perrin A, Beray-Berthat V et al. Infiltration of CD4+ lymphocytes into the brain contributes to neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto Y, Ito H, Ayaki T, Takahashi R. Immunohistochemical localization of apoptosome-related proteins in Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res 2014; 1571: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Fontana A, Cadas H, Schinelli S, Cimino G, Schwartz JC et al. Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature 1994; 372: 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz J, Romero J, Velasco G, Tolon RM, Ramos JA, Guzman M. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor: a new target for controlling neural cell survival? Trends Pharmacol Sci 2007; 28: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JP, Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Liu QR, Tagliaferro PA, Brusco A et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: immunohistochemical localization in rat brain. Brain Res 2006; 1071: 10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES. Neuropsychobiological evidence for the functional presence and expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the brain. Neuropsychobiology 2006; 54: 231–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter L, Franklin A, Witting A, Wade C, Xie Y, Kunos G et al. Nonpsychotropic cannabinoid receptors regulate microglial cell migration. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 1398–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchinetti F, Del Giudice E, Furegato S, Passarotto M, Leon A. Cannabinoids ablate release of TNFalpha in rat microglial cells stimulated with lypopolysaccharide. Glia 2003; 41: 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Moreno AM, Reigada D, Ramirez BG, Mechoulam R, Innamorato N, Cuadrado A et al. Cannabidiol and other cannabinoids reduce microglial activation in vitro and in vivo: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. Mol Pharmacol 2011; 79: 964–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez BG, Blazquez C, Gomez del Pulgar T, Guzman M, de Ceballos ML. Prevention of Alzheimer's disease pathology by cannabinoids: neuroprotection mediated by blockade of microglial activation. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 1904–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Gutierrez S, Molina-Holgado E, Guaza C. Effect of anandamide uptake inhibition in the production of nitric oxide and in the release of cytokines in astrocyte cultures. Glia 2005; 52: 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanikawa T, Kurohane K, Imai Y. Regulatory effect of cannabinoid receptor agonist on chemokine-induced lymphocyte chemotaxis. Biol Pharm Bull 2011; 34: 1090–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez D, Faustino J, Derugin N, Wendland M, Lizasoain I, Moro MA et al. Reduced infarct size and accumulation of microglia in rats treated with WIN 55,212-2 after neonatal stroke. Neuroscience 2012; 207: 307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murikinati S, Juttler E, Keinert T, Ridder DA, Muhammad S, Waibler Z et al. Activation of cannabinoid 2 receptors protects against cerebral ischemia by inhibiting neutrophil recruitment. FASEB J 2010; 24: 788–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amenta PS, Jallo JI, Tuma RF, Elliott MB. A cannabinoid type 2 receptor agonist attenuates blood-brain barrier damage and neurodegeneration in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res 2012; 90: 2293–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Fezza F, Galati S, Battista N, Napolitano S, Finazzi-Agro A et al. High endogenous cannabinoid levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of untreated Parkinson's disease patients. Ann Neurol 2005; 57: 777–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DA, Martinez AA, Seillier A, Koek W, Acosta Y, Fernandez E et al. WIN55,212-2, a cannabinoid receptor agonist, protects against nigrostriatal cell loss in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurosci 2009; 29: 2177–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YC, Bok E, Huh SH, Park JY, Yoon SH, Kim SR et al. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 protects nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons against MPTP neurotoxicity by inhibiting microglial activation. J Immunol 2011; 187: 6508–6517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YC, Kim SR, Park JY, Chung ES, Park KW, Won SY et al. Fluoxetine prevents MPTP-induced loss of dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting microglial activation. Neuropharmacology 2011; 60: 963–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YC, Kim YS, Bok E, Yune TY, Maeng S, Jin BK. MMP-3 contributes to nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuronal loss, BBB damage, and neuroinflammation in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Mediators Inflamm 2013; 2013: 370526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in thesubdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec 1991; 231: 482–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortekaas R, Leenders KL, van Oostrom JC, Vaalburg W, Bart J, Willemsen AT et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in parkinsonian midbrain in vivo. Ann Neurol 2005; 57: 176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani V, Stefani A, Pierantozzi M, Natoli S, Stanzione P, Franciotta D et al. Increased blood-cerebrospinal fluid transfer of albumin in advanced Parkinson's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2012; 9: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao YX, He BP, Tay SS. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation attenuates blood brain barrier damage and neuroinflammation and protects dopaminergic neurons against MPTP toxicity in the substantia nigra in a model of Parkinson's disease. J Neuroimmunol 2009; 216: 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lan X, Roche I, Liu R, Geiger JD. Caffeine protects against MPTP-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction in mouse striatum. J Neurochem 2008; 107: 1147–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH. Innate inflammation in Parkinson's disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2: a009373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale M, Iarlori C, Thomas A, Gambi D, Perfetti B, Di Nicola M et al. Peripheral cytokines profile in Parkinson's disease. Brain Behav Immun 2009; 23: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoji M, Pagan F, Healton EB, Mocchetti I. CXCR4 and CXCL12 expression is increased in the nigro-striatal system of Parkinson's disease. Neurotox Res 2009; 16: 318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaro MA, Cianciulli A. Current opinions and perspectives on the role of immune system in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Curr Pharm Des 2012; 18: 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease: a target for neuroprotection? Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 382–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC, Vyas S, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012; 18(Suppl 1): S210–S212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depboylu C, Stricker S, Ghobril JP, Oertel WH, Priller J, Hoglinger GU. Brain-resident microglia predominate over infiltrating myeloid cells in activation, phagocytosis and interaction with T-lymphocytes in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson disease. Exp Neurol 2012; 238: 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Episcopo FL, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, Marchetti B. Reactive astrocytes are key players in nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurorepair in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease: focus on endogenous neurorestoration. Curr Aging Sci 2013; 6: 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappold PM, Tieu K. Astrocytes and therapeutics for Parkinson's disease. Neurotherapeutics 2010; 7: 413–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila M, Jackson-Lewis V, Guegan C, Wu DC, Teismann P, Choi DK et al. The role of glial cells in Parkinson's disease. Curr Opin Neurol 2001; 14: 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki C, Watanabe Y, Yokoyama H, Shimoda T, Kato H, Araki T. Delayed treatment with arundic acid reduces the MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in mice. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2008; 28: 417–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin LM, Strycharska-Orczyk I, Murray R, Langston JW, Di Monte D. Increased vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons in MPTP-lesioned interleukin-6 deficient mice. J Neurochem 2002; 83: 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood 1998; 92: 3007–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnhold J, Flemmig J. Human myeloperoxidase in innate and acquired immunity. Arch Biochem Biophys 2010; 500: 92–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Ling Z, Newman MB, Bhatia A, Carvey PM. TNF-alpha knockout and minocycline treatment attenuates blood-brain barrier leakage in MPTP-treated mice. Neurobiol Dis 2007; 26: 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rite I, Machado A, Cano J, Venero JL. Blood-brain barrier disruption induces in vivo degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons. J Neurochem 2007; 101: 1567–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai BS, Monahan AJ, Carvey PM, Hendey B. Blood-brain barrier pathology in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease: implications for drug therapy. Cell Transplant 2007; 16: 285–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.