Abstract

Parallel advances in molecular imaging modalities and in gene- and cell-based therapeutics have significantly advanced their respective fields. Here we discuss how the collaborative, preclinical intersection of these technologies will facilitate more informed and effective clinical translation of relevant therapies.

In recent years, investigators have made impressive progress in the bench-to-bedside translation of gene- and stem cell-based therapies to address a wide range of pathologies in preclinical and clinical settings. Similar advances in bioimaging have provided powerful tools to monitor their in vivo fate and function. Here, we provide an overview of relevant gene- and cell-based therapy and highlight the applications of molecular imaging technologies to evaluate graft function, regulation, and interaction with host tissue. We emphasize particular strategies to facilitate the continued, collaborative synergy between molecular imaging technologies and gene- and stem cell-based therapeutics, which will expedite their assessment and development.

Clinical and preclinical experience

Corrective gene therapy in the clinics

Gene- and stem cell-based therapies hold potential to help treat a variety of diseases. Investigators have successfully illustrated the principle of isolating, engineering, and re-introducing a “corrected” graft for a variety of diseases with lineage-restricted phenotypes, including X-linked1 and adenosine deaminase deficient2 severe combined immunodeficiency disease, chronic granulomatous disease3, adrenoleukodystrophy4, and Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome5. These therapies, largely limited experimentally to retroviral insertion of the corrected gene product in autologously derived hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), have been met with widely publicized and appropriately directed concerns regarding their safety, despite encouraging demonstrations of phenotype correction. Follow-up reports have shown leukemic6 and pre-leukemic7 induction, clonal T cell expansion8, and genomic instability7 secondary to retroviral-mediated insertional mutagenesis in or near proto-oncogenes. Such events, due to untargeted genome editing, served as an impetus for the temporary Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ban on gene therapy in 2002. The subsequent lifting of the ban in 2003 heralded a more skeptical, and slow-progressing era that has continued to the present for a field yet to realize its full potential.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation in the clinics

Though the aforementioned near pause in gene therapy led to more cautious development in this arena, interest in autologous or allogeneic stem cell-based approaches strengthened significantly. Despite wide interest in use of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for a range of regenerative therapies, including those for inflammatory9, joint10, and cardiac diseases11, among others, questions regarding the clinical efficacy of various stem cell protocols remain. In addition to marginal improvement observed in several stem cell trials, there is also evidence of detrimental side effects as seen with skeletal myoblast therapy for cardiac repair12. The discrepancy between the more definitive preclinical success of stem cell therapies and their less promising early clinical results may be partly attributed to a lack of knowledge regarding in vivo graft behavior.

Promising new therapeutic products are now emerging, in particular those making use of human embryonic stem cell (hESC) and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derivatives. These include the now defunct Geron trial using allogeneic hESC-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells for spinal cord repair13, the Advanced Cell Technology trial using hESC-derived retinal pigment epithelium cells (RPEs) for Stargardt's macular dystrophy14, and the upcoming RIKEN Japan trial using autologous iPSC-derived RPEs for age-related macular degeneration15. As with earlier somatic cell therapies, pluripotent stem cell therapeutics will also need to be extensively tested and evaluated by bioimaging technologies to better understand their fate in vivo.

Genetically engineered stem cells

With the goal of optimizing clinical impact, the most promising approaches combine gene and cell therapy to deliver a corrected or beneficial gene in a therapeutically relevant cell. As an emerging paradigm, T cell immunotherapy offers hope for more targeted chemotherapy by genetically instructing T cell trafficking, direction, or redirection toward tumor cells, with the potential to engineer bi-specific T cells with engineered proliferation and anti-tumor specificities16. A noteworthy, single-patient case example of using PET imaging to track the fate of genetically-labeled and therapeutically-manipulated cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTLs) has demonstrated a valuable platform for integrating gene-cell therapy with molecular imaging17. In this report, CTLs labeled with the PET reporter gene herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) were infused intracranially after resection of a glioblastoma multiforme. PET imaging after administration of the PET reporter probe 9-(4-[18F]-fluoro-3-hydroxymethylbutyl)-guanine ([18F]FHBG) revealed not only accumulation of the engineered CTLs in the patient’s primary tumor but also homing to another metastatic site.

In addition to studying the in vivo fate of transplanted engineered cells, ex vivo edited cells also offer a valuable investigative platform. For instance, the ability to reprogram patient-specific adult somatic cells to iPSCs by overexpression of pluripotent transcription factors18 has been used for ex vivo disease modeling. Notable examples of recapitulating disease phenotypes in a dish include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis19, spinal muscular atrophy20, long QT syndrome21, and inherited cardiomyopathies22,23, among others. Beyond disease modeling, this platform has also expedited development of high-throughput drug screening24 as well as gene correction in monogenic diseases25.

Bioimaging

From disease modeling to disease monitoring

Gene- and stem cell-based approaches have suffered from a lack of knowledge and control over in vivo graft behavior. Requiring years of preclinical testing, their combined progression will need to overcome the obstacles that have impeded these approaches independently and should benefit significantly from insights gained from bioimaging of gene and stem cell fate. Historically, lineage mapping by physical or genetic labeling has contributed extensively to our understanding of development and stem cell behavior, and assisted in the isolation of important cell populations. To better understand why gene and cell therapies have fallen short of their potential to date, an approach similar to that taken by developmental biologists should be more fully adopted by molecular imaging specialists and translational researchers. The coupling of therapeutic cells or vectors to reporter cassettes to permit live, longitudinal imaging of cellular processes may provide key insights that will help elucidate and harness their full regenerative and corrective capacities, while simultaneously addressing safety and regulatory concerns (Figure 1)26,27.

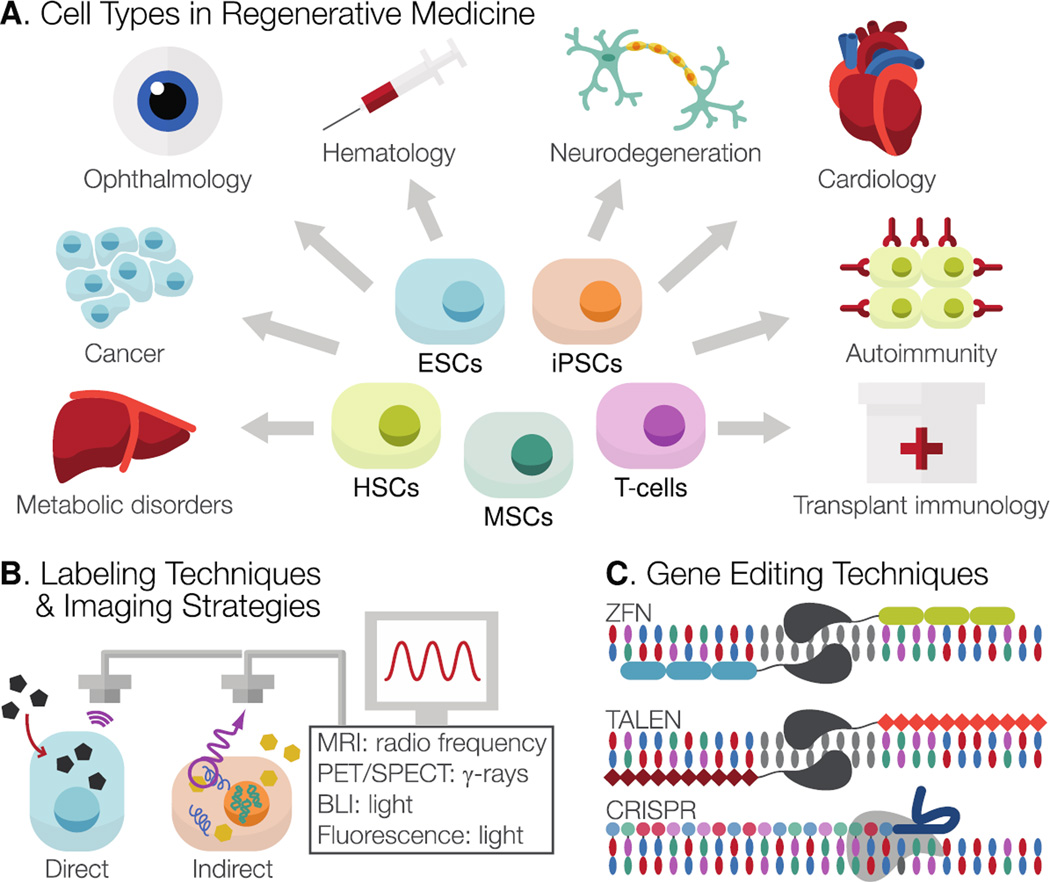

Figure 1. Pathways in gene- and cell-based therapies.

(A) A variety of cell types, including somatic cells (HSCs, T-cells) and pluripotent stem cell (ESCs, iPSCs) derivatives, are available to investigators to address a wide range of pathologies across fields. (B) To enable in vivo monitoring of transplanted cells by protein, enzyme, and receptor-based platforms, cells can be labeled either “directly” (with a physical compound such as iron particles or radiotracers) or “indirectly” (by genetic integration of reporter gene(s)). (C) Targeted genome editing can be achieved by several techniques, including ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR approaches. Dual editing of cells to integrate corrected gene products with reporter cassettes will facilitate informed assessment of their safety and efficacy by bioimaging. HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET/SPECT, positron emission tomography/single photon emission computed tomography; BLI, bioluminescent imaging; ZFN, zinc finger nuclease; TALEN, transcription activator-like effector nuclease; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats.

Defining and labeling the therapeutic population

Imaging Modalities

For regenerative medicine, several cell types are of interest due to their multipotent (e.g., MSCs) or pluripotent (e.g., ESCs and iPSCs) nature. Therapeutic applications of some of these cells have been explored through clinical trials, but unresolved concerns surrounding safety and efficacy are limiting their full clinical implementation28. Chief barriers to full regulatory acceptance of pluripotent stem cell-based therapeutics are their immunogenic and tumorigenic potential; addressing these will require in vivo tracking of transplanted grafts29. In vivo tracking of cell fate involves either “direct” physical labeling of cells by incubating them with a contrast agent, or “indirect” genetic labeling of cells by transfecting them with reporter gene construct(s). The position of and signal from these labels can then be tracked using a charged coupled device (CCD) camera for bioluminescence imaging30 or fluorescence imaging (FLI), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), among other modalities. Selection of the optimal labeling technique and imaging modality depends on the cellular processes that need to be studied as well as the read-outs that are most desirable, with each labeling and imaging strategy having distinct advantages and disadvantages31. To date, most clinical studies have relied on “direct” labeling strategies to track homing and migration of multipotent stem cells or engineered cells (see Table 1). These studies have answered critical questions in regenerative medicine, such as the importance of early stem cell engraftment on predicting late functional improvement32 and the optimal route of cell delivery (comparing transendocardial versus intracoronary routes) into the heart33. In addition, these cardiac regenerative studies highlight the importance of combining bioimaging of organ function with that of cell homing to assess which part of a diseased organ might benefit most from cell therapy34. For immunotherapy using modified cytolytic T-lymphocytes or tumor-specific dendritic cells (DCs), bioimaging has provided clinicians with important insight into the kinetics of anti-tumor cell infiltration into tumor tissue17,35. By using fluorinated (19F) contrast agents to label human DCs for MRI, pre-clinical studies have further demonstrated DC migration to draining lymph nodes, with superior assessment of cell quantity compared to that obtained by other MR imaging labels36,37.

Table 1. Clinical studies using in vivo bioimaging for tracking cell fate.

Human clinical trials or case reports using “direct” and “indirect” labeling strategies for in vivo bioimaging to monitor homing and migration of transplanted cells.

| Labeling: | Imaging Modality |

Cell type | Treatment | Procedure | Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18F–FHBG | PET/MRI | Cytolytic T-cells (CTL) (1×109 cells) |

Immunotherapy for glioblastoma multiforme |

|

|

17 |

| 18F-FDG | PET/CT | Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) (4.5×108) |

Cell therapy after myocardial infarction |

|

|

44 |

| SPIO + 111In-oxine |

MRI + Scintigraphy |

Dendritic cells (DC) (15×106 cells) |

Immunotherapy for melanoma |

|

|

35 |

| SPIO | MRI | Neural stem cells (NSC) |

Cell therapy for brain damage |

|

|

69 |

| 111In-oxine | PET | Circulating progenitor cells (CPC) (106 cells) |

Cell therapy after myocardial infarction |

|

|

45 |

| Technetium- 99m |

SPECT | Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNC) (~100×106) |

Cell therapy for non-ischemic DCM |

|

|

32, 33 |

18F-FHBG: Flurorine 18-9-[4-fluoro-3-(hydroxymethyl)butyl]guanine; 18F-FDG: Fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose; SPIO: super paramagnetic iron oxide; CPC: circulating progenitor cells; MI: myocardial infarction; 111In-oxine: indium oxine; Technetium-99m: 99mTc-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; HSV-tk: herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells

With the current focus on moving pluripotent stem cell derivatives to clinics38, in vivo tracking of these cells is critical in assessing their homing and proliferative potential over time, as well as the exclusion of teratoma formation39. In preclinical studies, more emphasis is placed on “indirect” genetic labeling over “direct” physical labeling because the former technique is not subject to signal dilution upon cell division nor discordance between signal intensity and cell viability upon graft loss40,41. Of note, label uptake by inflammatory cells may produce a false positive readout of graft persistence, due to uncoupling of the label from its original host cell42. Preclinical genetic labeling of stem cells with fluorescent proteins or bioluminescent enzymes has provided investigators with important information regarding graft behavior in small animal models, offering both fast read-outs of longitudinal cell survival and low costs per imaging study. However, the penetrance of these signals is too low for detection in humans, hence largely limiting their application to small animal models43. By contrast, PET and SPECT provide higher sensitivity than do optical techniques, making them better suited for monitoring biological processes in large animal and human studies17,32,33,44,45, while also sensitively permitting visualization of as low as 1×105 engrafted cells30. Although spatial resolution remains a limitation with nuclear medicine imaging, it could be overcome by combining with computed tomography46 (CT) or with MRI. However, the combined PET-CT approach may not be ideal for repetitive assessment of gene or stem cell fate due to the high exposure to ionizing radiation. Hence the combined PET-MRI approach may offer an attractive alternative because of its radiation-free and high spatial resolution qualities47.

Cell labeling strategies

Labeling cells to enable a combined PET-MRI approach will be of great clinical value for gene and cell therapies. Numerous PET reporter systems have been previously described, including those using dopamine-D2 and somatostatin receptors. However, these systems suffer from low sensitivity, as endogenous receptor expression leads to high background signal48–50. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS) has been proposed as an alternative reporter gene due to its wide substrate availability, labeling stability, and well-understood metabolism and substrate clearance51. However, the presence of NIS in other tissues such as the thyroid, stomach, and urinary tract reduces its reporter specificity. For PET imaging in gene and stem cell therapy settings, the most widely used label to date has been the HSV-tk reporter gene17,52–54. This construct offers several benefits, including quantitative and anatomic evaluation of reporter gene expression55. It also has the ability to function as a suicide gene upon administration of exogenous acycloguanosine substrates in pharmacological amounts, making it particularly ideal for ablating unwanted tumorigenic findings54.

For MRI, the chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) as a contrast agent has been used to improve detection sensitivity. It is based on the principle that mobile protons resonate at a frequency distinct from those in bulk fluid. A proton signal specific to a molecule or CEST substrate is selectively saturated with signal. These protons’ movement toward, exchange with, and subsequent signal transfer to bulk water results in the exchange transfer of signal loss56. While all 1H-based MR reporter genes rely on (super)paramagnetic substances and water relaxation for contrast57–59, the contrast produced by CEST agents can additionally be switched on and off by frequency selection. Using a lysine-rich protein (LRP) reporter, Gilad et al. demonstrated this principle by creating a contrast material that is detectable in the micromolar range, biodegradable, and capable of distinguishing live from dead cells, thus enabling the constant monitoring of endogenous expression levels in daughter cells60. Newer CEST contrast agents such as human protamine-1 address immunogenic concerns regarding the use of animal reporter proteins, and are being investigated for in vivo imaging applications61. Another advantage is that the separation of signals from different CEST contrast agents enable multiple, simultaneous measurements possible from distinct target populations62,63. In contrast to fusion reporter genes, the use of a single reporter gene for multimodal imaging with photoacoustics, MRI, and PET is being explored64.

Targeted genome editing

Significant advances have been made with respect to genome editing technologies, but these advances have not yet been extensively integrated with bioimaging tools. To date, the majority of genetic engineering to a targeted locus has been accomplished by use of zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs). More recently, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) have offered a similarly promising tool, coupling a generic FokI nuclease domain with a specific DNA-binding domain. For ZFNs and TALENs, DNA-binding modules are engineered to match a target DNA sequence. There, they direct double strand breaks and facilitate potential DNA alterations and repair under non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). A third genome editing system also offers strong potential for improving targeted gene therapies: the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) system uses RNA-guided Cas9 DNAse activity to generate sequence-specific target cleavage65.

To date, these three genome editing approaches have been used for correction or modeling of α1-antitrypsin disease66, sickle cell anemia67, and Parkinson’s disease68. Recently, Wang et al. demonstrated how ZFN technology can introduce a reporter cassette into the safe-harbor AAVS1 locus of human ESCs and iPSCs with readout capacity by three independent systems: bioluminescence imaging (Fluc), positron emission tomography imaging (HSV-tk), and fluorescence imaging (mRFP)27. This work provides a platform for future introduction of a dual reporter gene and corrected cassette under the control of the target site promoter, providing important insights into temporal and spatial activity of cell fate. Collectively, these three approaches (ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR) make potent tools for genomic targeting. Investigators now have the ability to (1) guide genomic integration of reporter genes and corrected genes, and (2) to monitor the behavior of edited grafts with bioimaging platforms.

Conclusions

Gene and stem cell therapies, individually or integrated into one therapeutic product, have yet to realize their full potential. Two significant hurdles are (1) a lack of regulatory confidence in the safety and specificity of genomic manipulations in gene correction or in cell differentiation, and (2) a lack of understanding into the long term survival kinetics and behavior of transplanted cells or integrated gene products. We propose here that bioimaging will play a critical role in overcoming these barriers by providing more quantitative and longitudinal readouts of graft and vector behavior, and lead to more informed and comprehensive patient care. The use of bioimaging in an integrated, collaborative approach will offer valuable insight into the delivery, engraftment, survival, and host tissue interactions of vectors and cells, as well as early knowledge of off-target behavior and oncogenic events. By providing powerful tools for guiding clinical practice and scientific development, bioimaging is assured of a bright future as a research field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from NIH HL093172, NIH EB009689, NIH HL095571, CIRM DR2A-05394, and CIRM TR3-05556 (JCW). Special thanks to Ryan Tucker and Christina Sicoli (Manuscript by Design) for figure design. Due to space limit, we are unable to include all of the important papers relevant to bioimaging; we apologize to the investigators who have made significant contributions to this field.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

None.

References

- 1.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, et al. Sustained correction of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by ex vivo gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1185–1193. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiuti A, et al. Gene therapy for immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:447–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott MG, et al. Correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease by gene therapy, augmented by insertional activation of MDS1-EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1. Nat Med. 2006;12:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartier N, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boztug K, et al. Stem-cell gene therapy for the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1918–1927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein S, et al. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nat Med. 2010;16:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howe SJ, et al. Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3143–3150. doi: 10.1172/JCI35798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffin MD, et al. Concise review: Adult mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for inflammatory diseases: How well are we joining the dots? Stem Cells. 2013;31:2033–2041. doi: 10.1002/stem.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry F, Murphy M. Mesenchymal stem cells in joint disease and repair. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:584–594. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheikh AY, et al. In vivo functional and transcriptional profiling of bone marrow stem cells after transplantation into ischemic myocardium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:92–102. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.238618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menasche P, et al. The Myoblast Autologous Grafting in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: first randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation. 2008;117:1189–1200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.734103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss S. Geron trial resumes, but standards for stem cell trials remain elusive. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:989–990. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz SD, et al. Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: a preliminary report. Lancet. 2012;379:713–720. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cyranoski D. Stem cells cruise to clinic. Nature. 2013;494:413. doi: 10.1038/494413a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kershaw MH, Westwood JA, Hwu P. Dual-specific T cells combine proliferation and antitumor activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1221–1227. doi: 10.1038/nbt756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaghoubi SS, et al. Noninvasive detection of therapeutic cytolytic T cells with 18F-FHBG PET in a patient with glioma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2009;6:53–58. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimos JT, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebert AD, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moretti A, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lan F, et al. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun N, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:130ra147. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mordwinkin NM, Lee AS, Wu JC. Patient-specific stem cells and cardiovascular drug discovery. JAMA. 2013;310:2039–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simara P, Motl JA, Kaufman DS. Pluripotent stem cells and gene therapy. Transl Res. 2013;161:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joung JK, Sander JD. TALENs: a widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nrm3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, et al. Genome editing of human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells with zinc finger nucleases for cellular imaging. Circ Res. 2012;111:1494–1503. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.274969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Almeida PE, Ransohoff JD, Nahid A, Wu JC. Immunogenicity of pluripotent stem cells and their derivatives. Circ Res. 2013;112:549–561. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kooreman NG, Wu JC. Tumorigenicity of pluripotent stem cells: biological insights from molecular imaging. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7(Suppl 6):S753–S763. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0353.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Templin C, et al. Transplantation and tracking of human-induced pluripotent stem cells in a pig model of myocardial infarction: assessment of cell survival, engraftment, and distribution by hybrid single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography of sodium iodide symporter transgene expression. Circulation. 2012;126:430–439. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Youn H, Chung JK. Reporter gene imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:W206–W214. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vrtovec B, et al. Effects of intracoronary CD34+ stem cell transplantation in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy patients: 5-year follow-up. Circ Res. 2013;112:165–173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.276519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vrtovec B, et al. Comparison of transendocardial and intracoronary CD34+ cell transplantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2013;128:S42–S49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musialek P, et al. Infarct size determines myocardial uptake of CD34+ cells in the peri-infarct zone: results from a study of (99m)Tc-extametazime-labeled cell visualization integrated with cardiac magnetic resonance infarct imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:320–328. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.979633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Vries IJ, et al. Magnetic resonance tracking of dendritic cells in melanoma patients for monitoring of cellular therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1407–1413. doi: 10.1038/nbt1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonetto F, et al. A novel (19)F agent for detection and quantification of human dendritic cells using magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:365–373. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helfer BM, et al. Functional assessment of human dendritic cells labeled for in vivo (19)F magnetic resonance imaging cell tracking. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:238–250. doi: 10.3109/14653240903446902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garber K. Inducing translation. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee AS, Tang C, Rao MS, Weissman IL, Wu JC. Tumorigenicity as a clinical hurdle for pluripotent stem cell therapies. Nat Med. 2013;19:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/nm.3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higuchi T, et al. Combined reporter gene PET and iron oxide MRI for monitoring survival and localization of transplanted cells in the rat heart. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1088–1094. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, et al. Comparison of reporter gene and iron particle labeling for tracking fate of human embryonic stem cells and differentiated endothelial cells in living subjects. Stem Cells. 2008;26:864–873. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amsalem Y, et al. Iron-oxide labeling and outcome of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells in the infarcted myocardium. Circulation. 2007;116:I38–I45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Contag CH, Bachmann MH. Advances in in vivo bioluminescence imaging of gene expression. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:235–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.111901.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang WJ, et al. Tissue distribution of 18F-FDG-labeled peripheral hematopoietic stem cells after intracoronary administration in patients with myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1295–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schachinger V, et al. Pilot trial on determinants of progenitor cell recruitment to the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2008;118:1425–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.777102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doyle B, et al. Dynamic tracking during intracoronary injection of 18F-FDG-labeled progenitor cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1708–1714. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wehrl HF, Judenhofer MS, Wiehr S, Pichler BJ. Pre-clinical PET/MR: technological advances and new perspectives in biomedical research. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(Suppl 1):S56–S68. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacLaren DC, et al. Repetitive, non-invasive imaging of the dopamine D2 receptor as a reporter gene in living animals. Gene Ther. 1999;6:785–791. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang Q, et al. Noninvasive, repetitive, quantitative measurement of gene expression from a bicistronic message by positron emission tomography, following gene transfer with adenovirus. Mol Ther. 2002;6:73–82. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwekkeboom DJ, et al. Somatostatin-receptor-based imaging and therapy of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R53–R73. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung JK. Sodium iodide symporter: its role in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1188–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Black ME, Newcomb TG, Wilson HM, Loeb LA. Creation of drug-specific herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase mutants for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3525–3529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu JC, et al. Molecular imaging of cardiac cell transplantation in living animals using optical bioluminescence and positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2003;108:1302–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091252.20010.6E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cao F, et al. In vivo visualization of embryonic stem cell survival, proliferation, and migration after cardiac delivery. Circulation. 2006;113:1005–1014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gambhir SS, et al. A mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase reporter gene shows improved sensitivity for imaging reporter gene expression with positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2785–2790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore A, Josephson L, Bhorade RM, Basilion JP, Weissleder R. Human transferrin receptor gene as a marker gene for MR imaging. Radiology. 2001;221:244–250. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2211001784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Genove G, DeMarco U, Xu H, Goins WF, Ahrens ET. A new transgene reporter for in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Med. 2005;11:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nm1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Louie AY, et al. In vivo visualization of gene expression using magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:321–325. doi: 10.1038/73780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gilad AA, et al. Artificial reporter gene providing MRI contrast based on proton exchange. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:217–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bar-Shir A, et al. Human Protamine-1 as an MRI Reporter Gene Based on Chemical Exchange. ACS Chem Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1021/cb400617q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McMahon MT, et al. New "multicolor" polypeptide diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer (DIACEST) contrast agents for MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:803–812. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu G, et al. In vivo multicolor molecular MR imaging using diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer liposomes. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1106–1113. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qin C, et al. Tyrosinase as a multifunctional reporter gene for Photoacoustic/MRI/PET triple modality molecular imaging. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1490. doi: 10.1038/srep01490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horii T, Tamura D, Morita S, Kimura M, Hatada I. Generation of an ICF Syndrome Model by Efficient Genome Editing of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Using the CRISPR System. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:19774–19781. doi: 10.3390/ijms141019774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yusa K, et al. Targeted gene correction of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;478:391–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sebastiano V, et al. In situ genetic correction of the sickle cell anemia mutation in human induced pluripotent stem cells using engineered zinc finger nucleases. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1717–1726. doi: 10.1002/stem.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soldner F, et al. Generation of isogenic pluripotent stem cells differing exclusively at two early onset Parkinson point mutations. Cell. 2011;146:318–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu J, Zhou L, XingWu F. Tracking neural stem cells in patients with brain trauma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2376–2378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc055304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.