Abstract

Background

To examine the source of advanced cancer patients' information about their prognosis and whether this source of information explains racial disparities in the accuracy of patients' life expectancy estimates (LEE).

Methods

Coping with Cancer is a prospective, longitudinal, multi-site study of terminally-ill cancer patients followed until death. In structured interviews, patients reported their LEE and the source of this estimate (i.e., medical provider, personal beliefs, religious beliefs, other). Accuracy of LEE was calculated by comparing patients' self-reported LEE to their actual survival.

Results

The sample for this analysis included 229 Black (n=31) and White (n=198) patients. Only 39.30% of the sample estimated their life expectancy within 12 months of actual survival. Black patients were more likely to have an inaccurate LEE than White patients. A minority of the sample (18.3%) reported that a medical provider was the source of their LEE; none (0%) of the Black patients based their LEE on a medical provider. Black race remained a significant predictor of an inaccurate LEE, even after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and source of LEE.

Conclusions

The majority of advanced cancer patients have an inaccurate understanding of their life expectancy. Black advanced cancer patients are more likely to have an inaccurate LEE than White patients. Medical providers are not the source of information for LEE for most advanced cancer patients, especially Black patients. The source of LEE does not explain racial differences in LEE accuracy. Additional research on mechanisms underlying racial differences in prognostic understanding is needed.

Keywords: Advanced cancer, racial disparities, life expectancy, end of life, illness understanding

Many advanced cancer patients lack an accurate understanding of their illness and prognosis.1,2 Advanced cancer patients tend to underestimate the severity of their diagnosis,3,4 view their prognosis in overly positive and unrealistic terms,5-7 and inaccurately believe that the goal of treatment is to cure their cancer.4,8 In recent studies of advanced cancer patients, fewer than 20% had an accurate understanding of their prognosis.7,9,10

These misunderstandings are related to patients' treatment decisions. Advanced cancer patients who do not recognize that their illness is terminal are more likely to prefer11,12 and receive aggressive care at the end of life (EoL).5,6 They are also less likely to discuss EoL care with their physicians,13 complete advance directives,7,13 receive care consistent with their preferences,12 and receive hospice services.11 Patients' estimates of their life expectancy are also related to their treatment preferences. Advanced cancer patients who believe they have at least a 90% chance of living 6 months or more prefer life extending care over palliative care at higher rates than patients with more realistic prognostic estimates (<90% chance of living 6 months).5

Inaccurate illness understanding is particularly prevalent and problematic among Black cancer patients. Despite similar rates of EoL care discussions with providers,14 Black patients are less likely to understand their illness and prognosis than White patients.15 In addition, Black patients are less likely to complete advance directives14-17 and receive hospice care17,18 and are more likely to receive aggressive EoL care14,18,19 and care inconsistent with their preferences14 than White patients.

Identifying factors that explain patients' understanding of their illness may identify ways to reduce racial disparities in advance care planning and EoL care. Numerous factors may contribute to Black/White disparities in illness and prognostic understanding including religious beliefs,17 care setting (rural versus urban),18 socioeconomic status,18,20 and effectiveness of EoL care discussions.14 However, the results of prior research are mixed.11,15,20 One unexamined factor that may explain cancer patients' misunderstanding of their prognosis and racial differences in this understanding is patients' source of information on their prognosis. The purpose of this study is to examine the source of advanced cancer patients' information on their prognosis and whether the source of this prognostic information explains racial disparities in patients' understanding of their prognosis.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Coping with Cancer (CwC) is a National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Mental Health-funded prospective, longitudinal, multi-site study of terminally-ill cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Patients were recruited from September 1, 2002 to February 28, 2008. Patients in the current sample were recruited from outpatient clinics at the Yale Cancer Center (New Haven, CT), Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System Comprehensive Cancer Clinics (West Haven, CT), Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center (Dallas, TX), Parkland Hospital Palliative Care Service (Dallas, TX), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA), Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA), and New Hampshire Oncology-Hematology (NHOH). Approval was obtained from the human subjects committees of all participating centers; all enrolled patients provided written consent and received $25 for their participation.

Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of metastatic cancer, disease progression after ≥ first-line chemotherapy, life expectancy of ≤6 months as determined by a member of the patient's healthcare team, patient age of 21 years or older, adequate stamina to complete study procedures, presence of an informal caregiver, absence of significant cognitive impairment in the patient and caregiver,21 and English or Spanish proficiency.

Trained research staff conducted a structured interview in English or Spanish with each patient at study entry. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. Patients were followed until death or study closure in March 2010. For patients surviving beyond closure of their participating site, date of death was obtained from the National Death Index (date of last death was in December 2011). We lacked the necessary information to conduct the National Death Index search for 99 patients; these patients were excluded from these analyses.

Of the 993 eligible patients, 726 patients (73.1%) completed the study measures. The most common reasons for nonparticipation were not interested (n=109), caregiver refused (n=33), and too upset (n=23). There were no differences between participants and nonparticipants, except that participants were more likely to be Hispanic (12.1% v. 5.8%, p=.005). However, for the current analysis, only patients who identified as non-Hispanic Black or White were included.

Measures

Demographic and Disease Characteristics

Self-reported demographic characteristics included age, education, gender, race, marital status, religious affiliation, and insurance status. Patient's cancer diagnosis was obtained from a medical record review at baseline. The Charlson Comorbidity Index, Karnofsky Performance Status, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status were obtained by trained research staff using a coding process that was applied uniformly across all patients.

Self-reported Life Expectancy Estimate (LEE) and Source of LEE

Self-reported LEE was assessed with a single item, “how long do you think you have left to live?” Patients provided their response in months and years. Participants were then asked to indicate the source of their LEE. Response options included: the oncologist, other clinic staff, a palliative care physician, the patient's personal belief, the patient's religious belief, and other. The response options of oncologist, other clinic staff, and palliative care physician were grouped into a single category of medical provider.

Accuracy of LEE

The accuracy of patients' LEE was calculated by comparing patients' self-reported LEE to their actual survival time. Patients' actual survival time was based on date of death. For patients who died within the study observation period, date of death was collected from patients' medical records. For patients who survived the study observation period, date of death was obtained from the National Death Index. Accuracy of patients' LEE was assessed with five indicators, the proportion of patients (yes/no) whose LEE fell within: 1) three months of actual survival, 2) six months of actual survival, and 3) 12 months of actual survival and the proportion of patients whose LEE differed by greater than 4) two years of actual survival and 5) five years of actual survival

Statistical Analysis

The relationships between race and patient demographic and disease characteristics were examined with Chi-Square or Fisher's exact test for binary characteristics and t-test or Wilcoxon Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous characteristics. The relationships between race and accuracy of patients' LEE and source of LEE were examined using logistic regression analyses and Fisher's exact test. Finally, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to examine the relationship between race and accuracy of patients' LEE controlling for patient demographic and disease characteristics and source of LEE. Using a forward selection model, demographic and disease characteristics significantly associated with race were entered into the models at a significance threshold of p<.2 and were retained in the final models if significant at p<.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The final sample consisted of 229 White (n=198, 86.5%) or Black (n=31, 13.5%) patients. The sample was 55% male with an average age of 60.1 years (SD=12.4). White patients were older (p=.03) with higher education levels (p<.001) and were more likely to be married (p=.03) and insured (p<.01). Black patients were less likely to be Catholic (p<.001) and more likely to be Pentecostal (p=.02) and Baptist (p=.004) than White patients. Black patients were also less likely to be recruited from Simmons Cancer Center (p=.03), DFCI/MGH (p=.01), and NHOH (p<.01) and more likely to be recruited from Parkland Hospital (p<.001) than White patients (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient demographic and baseline characteristics.

| Patient Characteristic | All Subjects (N=229) | White (N=198; 86.5%) | Black (N=31; 13.5%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age; Mean±SD | 60.1±12.4 (229) | 60.8±12.4 (198) | 55.7±11.7 (31) | 0.03 |

| Gender | 0.33 | |||

| Male | 55.0% (126/229) | 106 (53.5%) | 20 (64.5%) | |

| Female | 45.0% (103/229) | 92 (46.5%) | 11 (35.5%) | |

| Married | 64.8% (147/227) | 133 (67.9%) | 14 (45.2%) | 0.03 |

| Insured | 78.6% (176/224) | 167 (86.1%) | 9 (30.0%) | <.001 |

| Education; Mean±SD | 13.6±3.3 (229) | 13.9±3.2 (198) | 11.2±3.2 (31) | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 86.5% (198/229) | |||

| Black | 13.5% (31/229) | |||

| Religion | ||||

| Catholic | 38.9% (89/229) | 86 (43.4%) | 3 (9.7%) | <.001 |

| Protestant | 21.8% (50/229) | 44 (22.2%) | 6 (19.4%) | 0.82 |

| Jewish | 4.4% (10/229) | 10 (5.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.37 |

| Muslim | 0.4% (1/229) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.14 |

| No religion | 7.4% (17/229) | 16 (8.1%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.48 |

| Pentecostal | 0.9% (2/229) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.5%) | 0.02 |

| Baptist | 9.6% (22/229) | 14 (7.1%) | 8 (25.8%) | 0.004 |

| Recruitment Site | ||||

| Yale Cancer Center | 19.3% (44/228) | 38 (19.3%) | 6 (19.4%) | 1.000 |

| Veterans Affairs | 4.8% (11/228) | 10 (5.1%) | 1 (3.2%) | 1.000 |

| Simmons Center | 11.0% (25/228) | 25 (12.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.03 |

| Parkland Hospital | 20.2% (46/228) | 22 (11.2%) | 24 (77.4%) | <.001 |

| DFCI/MGHa | 14.0% (32/228) | 32 (16.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.01 |

| NHOHb | 30.3% (69/228) | 69 (35.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <.001 |

| Cancer Type | 0.214 | |||

| Lung | 26.2% (59/225) | 48 (24.6%) | 11 (36.7%) | 0.183 |

| Pancreatic | 7.6% (17/225) | 16 (8.2%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.708 |

| Colon | 11.6% (26/225) | 21 (10.8%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.358 |

| Brain | 3.1% (7/225) | 7 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.598 |

| Stomach | 0.9% (2/225) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.249 |

| Esophageal | 4.9% (11/225) | 11 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.367 |

| Performance Status; Mean±SD (N) | ||||

| Karnofsky Score | 67.3±17.0 (220) | 66.9±17.5 | 69.7±13.8 | 0.415 |

| Zubrod Score | 1.7±0.9 (222) | 1.7±0.9 | 1.6±0.8 | 0.504 |

| Charlson Index | 8.3±3.7 (225) | 8.5±3.9 | 7.5±2.2 | 0.061 |

DFCI=Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; MGH=Massachusetts General Hospital.

NHOH=New Hampshire Oncology Hematology.

Race and Accuracy of Life Expectancy Estimates

Only 11.79% of the sample accurately estimated their life expectancy within three months of actual survival (Table 2). Approximately one-quarter of the sample (25.33%) accurately estimated life expectancy within six months of survival and 39.30% accurately estimated within 12 months of survival. Further, the LEE of 43.67% of the sample differed from actual survival by more than two years and the LEE of 27.95% differed by more than five years.

Table 2. Relationship between race (Black/White) and the accuracy of patients' self-estimates of life expectancy, N=229.

| Race; n(%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| LEE Accuracya | Total sample n(%) | White (N=198) | Black (N=31) | OR (95% CI)b | p-value |

| Within +/-3 months of actual survival | 27 (11.79) | 25 (12.63) | 2 (6.45) | 2.10 (0.47-9.33) | .33 |

| Within +/-6 months of actual survival | 58 (25.33) | 54 (27.27) | 4 (12.90) | 2.53 (0.85-7.57) | .10 |

| Within +/-12mos of actual survival | 90 (39.30) | 86 (43.43) | 4 (12.90) | 5.18 (1.75-15.37) | .003 |

| Differed by more than 2 years of actual survivalc | 100 (43.67) | 76 (38.38) | 24 (77.42) | 0.18 (0.08-0.44) | <.001 |

| Differed by more than 5 year of actual survivald | 64 (27.95) | 44 (22.22) | 20 (64.52) | 0.16 (0.07-0.35) | <.001 |

Patients with LEE within 3 months of actual survival are included in the proportion of patients with LEE within 6 and 12 months of actual survival; patients with LEE within 6 months of actual survival are included in the proportion of patients with LEE within 12 months of actual survival. Patients whose LEE differed from actual survival by 5 years are included in the proportion whose LEE differed by 2 years.

White=1, Black=0

97 patients overestimated their life expectancy by more than 2 years and 3 patients underestimated their life expectancy by more than 2 years.

All 64 patients overestimated by more than 5 years.

White patients were more likely to accurately estimate their survival within 12 months of actual survival than Black patients (Table 2; OR, 5.18; 95% CI, 1.75, 15.37; p=.003). The LEE of White patients was also less likely to differ from actual survival by two (OR, .18; 95% CI, .08, .44; p<.001) and five years (OR, .16; 95% CI, .07, .35; p<.001) than the LEE of Black patients. Only 12.90% of Black patients' LEE were within 12 months of actual survival, 77.42% differed from actual survival by at least two years, and 64.52% differed by at least five years. Racial differences in LEE accuracy within three and six months of actual survival were not significant (p's>.05).

Race and Source of Life Expectancy Estimates

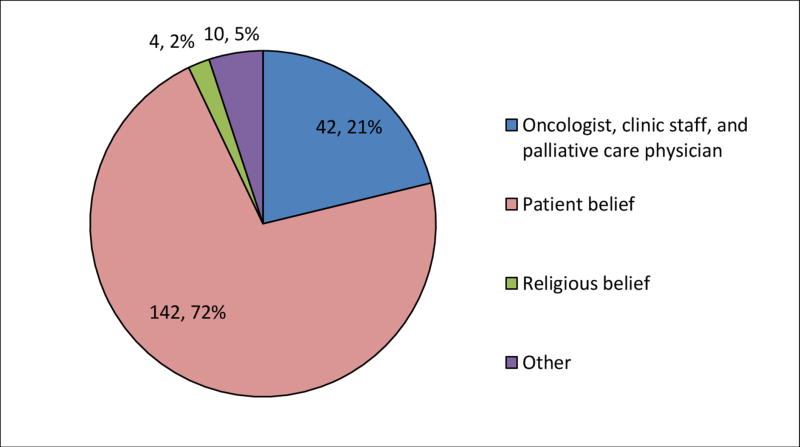

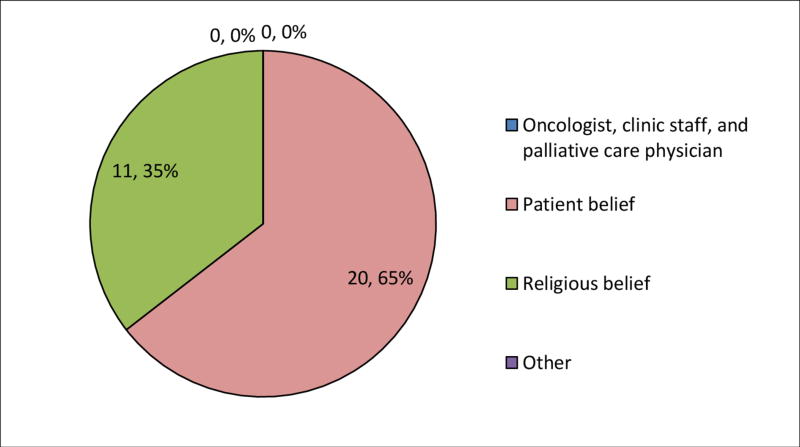

Less than one-fifth of the total sample (18.3%) reported that a medical provider was the source of their LEE. The majority of the sample (70.7%) reported basing their LEE on personal beliefs; 6.6% based their LEE on their religious beliefs. White patients were more likely to base their LEE on a medical provider than Black patients (p<.001; Table 3 and Figures 1 and 2). Notably, none (0%) of the Black patients reported that a medical provider was the source of their LEE. Black patients were more likely to base their LEE on their religious beliefs than White patients (OR, .04; 95% CI, .01, .13; p<.001).

Table 3. Relationship between race and source of life expectancy estimate (LEE), N=229.

| Race | Logistic Regression Analyses | Fisher's Exact | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of LEE | Total sample | White | Black | OR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value |

| Medical provider | 42 (18.3%) | 42 (21.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | -----* | ------ | <.001 |

| Patient belief | 162 (70.7%) | 142 (71.7%) | 20 (64.5%) | 1.40 (0.63-3.10) | .4138 | <.001 |

| Religious belief | 15 (6.6%) | 4 (2.0%) | 11 (35.5%) | 0.04 (0.01-0.13) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Other | 10 (4.4%) | 10 (5.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Total | 229 | 198 (86.5%) | 31 (13.5%) | |||

OR cannot be estimated due to the sparseness of the data.

Figure 1. Source of life expectancy estimates for White patients (n=198).

Figure 2. Source of life expectancy estimates for Black patients (n=31).

Race and Source of LEE Predicting LEE Accuracy

Race and source of LEE were not significantly associated with LEE within three and six months of actual survival in bivariate analyses (ps>.05). Additional analyses predicting these indicators of LEE accuracy were not conducted. In univariable analyses predicting LEE within 12 months of actual survival (Table 4), patients who reported that their medical provider was the source of their LEE were almost 2.5 times more likely to have an accurate LEE than patients who did not rely on a medical provider (OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.24, 4.83; p=.01). In multivariable analyses predicting LEE within 12 months of actual survival, patients who were White (OR, 3.54; 95% CI, 1.13, 11.07; p=.03), not married (OR, .52; 95% CI, .28, .98; p=.04), and recruited from NHOH (OR, 4.71; 95% CI, 2.48, 8.94; p<.001) were more likely to have an accurate LEE. Source of LEE was not associated with LEE accuracy in multivariable analyses.

Table 4. Analysis of race and LEE source predicting accuracy of patient's LEE within 12 months of actual survival, N=229.

| LEE within 12 months actual survival, n(%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Yes (N=90; 39.3) | No(N=139; 60.7) | Univariable Regression | Multivariable Regression | |||

| Sample Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| White | 86 (95.6) | 112 (80.6) | 5.18 (1.75-15.37) | .003 | 3.54 (1.13-11.07) | .03 |

| Age; Mean±SD | 63.2±12.3 | 58.1±12.1 | 1.04 (1.01-1.06) | .003 | ||

| Married | 52 (59.1) | 95 (68.3) | 0.67 (0.38-1.17) | .16 | 0.52 (0.28-0.98) | .04 |

| Insured | 73 (83.9) | 103 (75.2) | 1.72 (0.86-3.43) | .12 | ||

| Education; Mean±SD | 13.6±3.2 | 13.5±3.4 | 1.00 (0.92-1.09) | .96 | ||

| Catholic | 46 (51.1) | 43 (30.9) | 2.33 (1.35-4.04) | .002 | ||

| Muslim | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0.00 (0.00-I) | .99 | ||

| Pentecostal | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 (0.00-I) | .99 | ||

| Baptist | 5 (5.6) | 17 (12.2) | 0.42 (0.15-1.19) | .10 | ||

| Study site | ||||||

| Simmons Center | 4 (4.4) | 21 (15.2) | 0.26 (0.09-0.78) | .02 | ||

| Parkland Hospital | 13 (14.4) | 33 (23.9) | 0.54 (0.27-1.09) | .09 | ||

| DFCI/MGHa | 10 (11.1) | 22 (15.9) | 0.66 (0.30-1.47) | .31 | ||

| NHOHb | 47 (52.2) | 22 (15.9) | 5.76 (3.11-10.66) | <.001 | 4.71 (2.48-8.94) | <.001 |

| Lung cancer | 27 (30.3) | 32 (23.5) | 1.42 (0.78-2.58) | .26 | ||

| Charlson Index; Mean±SD | 9.0±3.0 | 7.9±4.1 | 1.09 (1.00-1.20) | .06 | ||

| LEE Source | ||||||

| Medical Provider | 24 (26.7) | 18 (12.9) | 2.44 (1.24-4.83) | .01 | ||

| Personal Belief | 60 (66.7) | 102 (73.4) | 0.73 (0.41-1.29) | .28 | ||

| Religious Belief | 3 (3.3) | 12 (8.6) | 0.36 (0.10-1.33) | .13 | ||

DFCI=Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; MGH=Massachusetts General Hospital.

NHOH=New Hampshire Oncology Hematology.

Note. Accurate within 12 months: No=0, Yes=1; Marital status: Other=0, Married=1; Insured: No=0, Yes=1; White: No-0, Yes=1; Religious affiliations: No=0, Yes=1; Study sites: No=0, Yes=1; Lung cancer: No=0, Yes=1; LEE source: No=0, Yes=1.

Patients whose LEE was based on a medical provider were over two times less likely to report a LEE that differed by two years from actual survival than patients who did not rely on a medical provider in bivariate analyses (OR, .45; 95% CI, .22, .93; p=.03; data not shown). In multivariable analyses predicting LEE that differed by two years from actual survival, Black race (OR, .27; 95% CI, .11, .68; p<.01) and personal belief as the source of LEE (OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.25, 4.70; p<.01) were associated with greater likelihood of an inaccurate LEE. Patients recruited at NHOH were also less likely to report an inaccurate LEE in multivariable analyses (OR, .16; 95% CI, .08, .35; p<.001),

In univariable analyses, patients who based their LEE on a medical provider were over three times more likely to have an accurate LEE than patients who did not rely on a medical provider (OR, .29; 95% CI, .11, .78; p=.02; data not shown). Basing LEE on religious beliefs was associated with over four times greater likelihood of a LEE that differed by five years from actual survival (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 1.48, 12.74; p=.01). In multivariable analyses, recruitment at DFCI/MGH (OR, .33; 95% CI, .11, .94; p<.05) and NHOH (OR, .10; 95% CI, .03, .29; p<.001) were associated with less likelihood of an inaccurate LEE. In addition, Black race (OR, .39; 95% CI, .17, .94; p<.05) was associated with greater likelihood of a LEE greater than five years of actual survival. Patients who based their LEE on a medical provider were more likely to have an accurate LEE (OR, .32; 95% CI, .11, .91; p<.05).

Discussion

This study examined the source of Black and White advanced cancer patients' information on their life expectancy and the relationship between race and source and accuracy of patients' LEE. The majority of the sample reported inaccurate LEE and Black patients were more likely to have inaccurate LEE than White patients. Less than one-fifth of patients reported basing their LEE on information from a medical provider. Black patients were less likely to base LEE on medical providers than White patients. In fact, no Black patients reported basing their LEE on information from medical providers. In univariable analyses, basing LEE on a medical provider was associated with more accurate LEE while basing LEE on religious beliefs was associated with less accurate LEE. However, racial differences in LEE accuracy remained after controlling for source of LEE. Black race was associated with greater likelihood of inaccurate LEE after controlling for sociodemographic and disease characteristics and source of LEE.

The small proportion of patients who reported basing their LEE on information from their medical providers is concerning. An advanced cancer patient's life expectancy is determined primarily by characteristics of the patient's disease and treatment response,22,23 which is the expertise of the medical team. Yet, patients are not basing their LEE on the source most able to provide accurate information. This pattern may explain research indicating that advanced cancer patients frequently do not understand the terminal nature of their illness.5,6,9,11,15 These findings are problematic in light of evidence that patients who over-estimate their prognosis are less prepared for EoL and prefer and receive more aggressive EoL care,5,11 which has been associated with greater distress and worse quality of life and death in patients and worse bereaved caregiver adjustment.24,25

Rather than relying on their medical providers, the majority of both Black and White patients in this study reported basing their LEE on their “personal beliefs.” “Religious beliefs” was an alternative response option for this item; therefore, we can assume that these “personal beliefs” are not religious in nature. Outside of this, however, the characteristics, content, and source of these beliefs are unclear. Additional research is needed to understand the nature of these beliefs.

Racial differences in the source of prognostic information were striking. Notably, none of the Black patients reported basing their LEE on information from medical providers. This finding is concerning in light of evidence that minority cancer patients are more likely to receive aggressive care at the end-of-life than White patients19 and are less likely to receive EOL care consistent with their stated preferences.14,19 Black cancer patients have less trust in the healthcare system and medical providers than White patients.26,27 This mistrust may explain Black patients' tendency to rely on other sources of information for their LEE to a greater degree than White patients. Further, the majority of oncologists are White28 and do not share the cultural and educational background of their Black patients which may impact communication29 and reduce patients' willingness to rely on the information provided by their medical providers.

Black patients were also more likely to base their LEE on their religious beliefs than White patients. Across studies, racial minorities endorse higher levels of religiosity and greater use of religion to cope.27 This study adds to this body of work by suggesting that Black patients also rely on their religious beliefs to explain specific aspects of their cancer. Integrating Black patients' religious beliefs into patient-provider discussions of prognosis may be a culturally sensitive strategy for improving patients' understanding of prognostic information.

After controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and source of LEE, race remained a significant, albeit slightly weaker, predictor of LEE accuracy. Black patients were two to three times less likely to have an accurate LEE than White patients in adjusted analyses. These findings indicate that source of LEE is important but does not completely explain racial differences in prognostic understanding. Racial categories place a single label on complex cultural beliefs and values that vary across and within racial groups. Given this complexity, it is not surprising that single indicators such as source of LEE do not account for racial differences in prognostic understanding. However, source of LEE may be one factor that contributes to racial differences in prognostic understanding. Further, the relationship between source and accuracy of LEE in this study suggests that source of LEE is an important factor to consider when attempting to improve patients' understanding of their illness.

This study is limited by the small sample of Black patients and a cross-sectional design that does not allow for examination of changes in patients' LEE over time. In addition, these results cannot be generalized to patients with diseases other than advanced cancer and patients of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. Research on patients with other terminal illnesses and from different racial and ethnic backgrounds such as Hispanic and Asian-Americans will provide insight on strategies for tailoring prognostic discussions to meet the unique needs of a greater range of diverse patient populations. Further, due to the small number of patients who reported basing their LEE on palliative care physicians and other clinic staff, we were unable to examine differences in LEE accuracy across different medical providers. Future research that examines differences in LEE accuracy across providers will provide insight into the most effective source of this information for Black and White advanced cancer patients. Finally, the majority of the sample over-estimated their life expectancy. As a result, we were unable to examine differences between patients who over- and under-estimated their life expectancy. Over-estimation of life expectancy likely has different implications for patients' psychosocial well-being, advance care planning, and treatment decisions than under-estimation. Understanding predictors of over- versus under-estimation, including racial and ethnic differences will provide a more detailed understanding of various ways in which patients misunderstand their illness, identify patients at risk for over- and under-estimation, and inform interventions to correct unique types of illness misunderstanding. Despite these limitations, this study points to the need for culturally sensitive communication training programs for medical providers that consider patients' religious and personal beliefs. However, it is important to note that the source of patients' LEE did not explain racial differences in accuracy of LEE.

Ongoing research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying racial differences in patients' understanding of their illness. Important factors to explore include the timing, source, and content of discussions of patients' prognosis and how Black and White patients understand and utilize this information to make treatment decisions. In addition, explication of the nature of patients' religious and personal beliefs related to prognostic understanding will allow providers to integrate these beliefs into prognostic discussions. Due to the personal and potentially individualized nature of these beliefs, mixed methods research designs that provide both an in-depth and aggregate view of these factors will be important. These findings will inform targeted interventions to improve all patients' illness understanding and to reduce racial disparities in illness understanding.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported in part by the following grants: MH63892 (HGP) from the National Institute of Mental Health, CA106370 (HGP) and CA197730 (HGP) from the National Cancer Institute, MD007652 (PKM, HGP) from the National Institute on Minority Heath and Health Disparities, and K23AG048632 (KMT) from the National Institute on Aging and American Federation for Aging Research.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conception and design: All authors; Financial support: HGP, KMT; Administrative support: HGP; Provision of study materials or patients: HGP; Collection and assembly of data: BZ, HGP; Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; Manuscript writing: All authors; Final approval of manuscript: All authors

There are no conflicts of interest for any author.

References

- 1.Applebaum AJ, Kolva EA, Kulikowski JR, et al. Conceptualizing prognostic awareness in advanced cancer: a systematic review. Journal of health psychology. 2014;19(9):1103–1119. doi: 10.1177/1359105313484782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond EL, Corner GW, De Rosa A, Breitbart W, Applebaum AJ. Prognostic awareness and communication of prognostic information in malignant glioma: a systematic review. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2014;119(2):227–234. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1487-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sapir R, Catane R, Kaufman B, et al. Cancer patient expectations of and communication with oncologists and oncology nurses: the experience of an integrated oncology and palliative care service. Supportive care in cancer: Official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2000;8(6):458–463. doi: 10.1007/s005200000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park ER, et al. Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(2):278–285. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(17):2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of Prognostic Disclosure: Associations With Prognostic Understanding, Distress, and Relationship With Physician Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(32):3809–3816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(17):1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Perceptions of Health Status and Survival in Patients With Metastatic Lung Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC, et al. Physicians' propensity to discuss prognosis is associated with patients' awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(6):673–682. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright AA, Mack JW, Kritek PA, et al. Influence of patients' preferences and treatment site on cancer patients' end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116(19):4656–4663. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(7):1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray A, Block SD, Friedlander RJ, Zhang B, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Peaceful awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(6):1359–1368. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Archives of internal medicine. 2010;170(17):1533–1540. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(25):4131–4137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrido MM, Harrington ST, Prigerson HG. End-of-life treatment preferences: A key to reducing ethnic/racial disparities in advance care planning? Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, Harralson T, Harris D, Tester W. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: the role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Annals of behavioral medicine: A publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30(2):174–179. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nayar P, Qiu F, Watanabe-Galloway S, et al. Disparities in End of Life Care for Elderly Lung Cancer Patients. Journal of community health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(33):5559–5564. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tucker-Seeley RD, Abel GA, Uno H, Prigerson H. Financial hardship and the intensity of medical care received near death. Psycho-oncology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pon.3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnan MS, Epstein-Peterson Z, Chen YH, et al. Predicting life expectancy in patients with metastatic cancer receiving palliative radiotherapy: the TEACHH model. Cancer. 2014;120(1):134–141. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan M, Temel JS, Wright AA, Bernacki R, Selvaggi K, Balboni T. Predicting life expectancy in patients with advanced incurable cancer: a review. The journal of supportive oncology. 2013;11(2):68–74. doi: 10.12788/j.suponc.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(29):4457–4464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin JJ, Mhango G, Wall MM, et al. Cultural factors associated with racial disparities in lung cancer care. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2014;11(4):489–495. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201402-055OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song L, Weaver MA, Chen RC, et al. Associations between patient-provider communication and socio-cultural factors in prostate cancer patients: a cross-sectional evaluation of racial differences. Patient education and counseling. 2014;97(3):339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center for Workforce Studies. Forecasting the Supply of and Demand for Oncologists: A Report to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) from the AAMC Center for Workforce Studies. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eggly S, Barton E, Winckles A, Penner LA, Albrecht TL. A disparity of words: racial differences in oncologist-patient communication about clinical trials. Health expectations: An international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. 2015;18(5):1316–1326. doi: 10.1111/hex.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]