Abstract

Context

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention evaluated the economics of the National Program of Cancer Registries to provide the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the registries, and policy makers with the economic evidence-base to make optimal decisions about resource allocation. Cancer registry budgets are under increasing threat, and, therefore, systematic assessment of the cost will identify approaches to improve the efficiencies of this vital data collection operation and also justify the funding required to sustain registry operations.

Objectives

To estimate the cost of cancer registry operations and to assess the factors affecting the cost per case reported by National Program of Cancer Registries–funded central cancer registries.

Methods

We developed a Web-based cost assessment tool to collect 3 years of data (2009-2011) from each National Program of Cancer Registries–funded registry for all actual expenditures for registry activities (including those funded by other sources) and factors affecting registry operations. We used a random-effects regression model to estimate the impact of various factors on cost per cancer case reported.

Results

The cost of reporting a cancer case varied across the registries. Central cancer registries that receive high-quality data from reporting sources (as measured by the percentage of records passing automatic edits) and electronic data submissions, and those that collect and report on a large volume of cases had significantly lower cost per case. The volume of cases reported had a large effect, with low-volume registries experiencing much higher cost per case than medium- or high-volume registries.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that registries operate with substantial fixed or semivariable costs. Therefore, sharing fixed costs among low-volume contiguous state registries, whenever possible, and centralization of certain processes can result in economies of scale. Approaches to improve quality of data submitted and increasing electronic reporting can also reduce cost.

Keywords: cancer registry, cost, economics

Cancer is the second leading cause of death among people in the United States, responsible for approximately 1 in 4 deaths.1 During 2011, more than 1.5 million people in the United States were diagnosed with cancer, and more than half a million died of their cancers.2 Cancer accounts for approximately 5% of overall national health care expenditures.3,4 Information from cancer registries is used to track cancer trends; assess cancer disparities; assess progress toward cancer prevention and control objectives, including those established by Healthy People 2020; and identify additional needs for cancer prevention and control efforts at national, state, and local levels (http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/about.htm/).

The National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) (http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/about.htm) is administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and provides financial and technical support for the operation of central population-based cancer registries. Currently, the NCPR funds 45 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Pacific Island Jurisdictions. Cancer registries in some states and metropolitan areas are also funded by the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program (http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/). Together, the NPCR and the SEER collect data for the entire US population.

Although NPCR has been funded by Congress since 1994, no comprehensive study of the economic costs incurred by the NPCR has been conducted. A previous study used federal funding sources to estimate the average cost per case reported by NPCR-funded registries and to identify factors that explain state variations.5 This study underestimated the true costs because other sources of funding were not included, such as state government funds, and in-kind contributions.6-8 Understanding the true cost of cancer registration is essential to forecast funding requirements, identify resources required to enhance data collection activities, and also to assess efficiencies in data collection approaches. It is also important to systematically quantify the resources required to ensure that high-quality cancer registry data are collected and reported.

The objective of the current study is to estimate the cost of reporting a cancer case by the NPCR-funded registries and to assess the factors affecting the cost per case reported. Prior studies have shown that there are potentially large variations in cost per case among registries.6-8 Central cancer registries are complex and perform many activities, including those related to core surveillance (ie, activities related to data collection and development of the registry database) and advanced activities (such as active follow-up and implementing cancer inquiry response systems to improve quality and completeness of the registry data). Cancer registry budgets are under increasing threat, and, therefore, systematic assessment of the cost will identify approaches to improve the efficiencies of this vital data collection operation and also justify the funding required to sustain registry operations to report high-quality data.

Methods

We collected 3 years (fiscal years 2009-2011) of data on funding, cost of operations (including in-kind contributions), and factors that affect the efficiency of operating central cancer registries. Three years of data were collected to allow for a more precise analysis of registry costs and cost per case reported, as well as the sample size necessary to conduct the regression-based analysis presented in this study. The nature of registry operations may result in significant variation in registry activities and, therefore, costs from year to year. In addition, because case reporting may be delayed and data collection for a given case continues over many years, the number of cases reported in any given reporting period may not result in accurate assessments; longer study time periods should result in better estimation.8

Cost data collection

A Web-based Cost Assessment Tool was developed to collect activity-based cost data from the 48 NPCR-funded registries.7,9-11 Details on the development of the tool and the pilot-testing process have been previously reported.7 Cost data were collected across the following budget categories: labor, consultant and contract expenditures, computer software and hardware, travel and training, and administrative or overhead expenses.

The programmatic perspective was used for the analysis, and, therefore, all funding and costs relevant to the program operations were collected. Registries reported funding from 3 types of sources: NPCR funds, other federal funds, and nonfederal funds. Registries provided data about actual (rather than budgeted) cost incurred and information on all in-kind labor and non-labor contributions. Registry staff members were asked to allocate cost and employee time to standardized registry activities. In-house labor (registry staff) is the largest cost incurred by cancer registries, and, therefore, in-depth assessment of staff time spent on activities was undertaken to ensure accurate generation of activity-based costs. In addition, staff compensation was collected using specific detailed categories to ensure all costs related to salary and fringe benefits were captured.

In general, information technology and equipment (eg, computers and office furniture) were covered through the indirect or overhead cost contributions. Many of the registries also used software provided by the CDC, which is available free of charge. Registry operations are complex, and on the basis of preliminary review, we determined that it would not be possible to accurately determine fixed, semifixed, and variable components and, therefore, we did not classify costs into these categories. No information on resources expended by hospitals and other reporting sources to provide data to cancer registries is included in this analysis, as this study uses a programmatic (cancer registry program) perspective. To ensure that data were consistently reported across the registries, registry staff were offered the following: webinar-based training, a user's guide with detailed definitions of each core and advanced activity, and ongoing technical assistance to address any questions about data collection and reporting.

Incidence cases studied

National Program of Cancer Registries–funded registries report all invasive cancers diagnosed among residents of their state on an annual basis to the CDC. In addition to these reporting requirements, many registries collect additional cases. These may include cases reported by SEER registries, cases reported for research purposes, and cases diagnosed in other states. Out-of-state incidence cases may be shared with the appropriate registry through case-sharing agreements. To standardize cost per case calculations, we limited the cases reported to in-state cases collected by the registry.

Calculating cost per case of cancer reported

Following data validation, we derived activity-based cost estimates for each registry. First, we allocated costs to specific registry activities by summing the cost of each registry activity across all budget categories (eg, personnel costs were allocated across activities on the basis of the reported percentage time spent on each activity). Next, we added together expenditures that did not have any associated registry activity and prorated those costs across all registry activities. Then, we calculated cost per case, both overall and by registry activity. Finally, we classified the cost into core and advanced activities. Cost per case values were adjusted to 2011 dollars to account for regional cost of living differences by using the Employment Cost Index.12

Factors affecting cost per case

Region, representing population size and geographic area, is one characteristic that may affect the cost of registry operations beyond variations in costs across regions. CDC uses the US Census regions (Northeast, South, Midwest, or West) for each registry, with the exception of Puerto Rico and the Pacific Island Jurisdictions which are not part of any census region or census division.13 The number of cases collected or the time required to collect data from dispersed data sources may affect the cost of collecting cancer incidence data. We identified population size as low (below 2.8 million people), medium (2.8-6 million people), or high (>6 million people) on the basis of the US Census Bureau population estimates for 2011, and we classified geographic area as small (<42 000 square miles), medium (42 000-69 000 square miles), or large (>69 000 square miles).

Case volume and consolidation effort are both likely to drive cost per case. Case volume is the number of incidence cases diagnosed during a given year and collected by the registry. We classified case volume as low (<10 000 cases), medium (10 000-50 000 cases), and high (>50 000 cases). These cut points were determined by review of the data; medium volume represents most of the registries, with low and high volume identifying outliers. The map in Figure 1 illustrates the volume of incidence cases reported (case volume).

Figure 1. Map of US Cancer Registries With Volume of Incident Cancer Cases Recorded by Cancer Registries by Statea.

Abbreviation: NPCR, National Program of Cancer Registries. aOur analysis excludes Pacific Island Jurisdictions. The registry did not report cases diagnosed in 2006 and is still ramping up case reporting. Low case volume distorts cost per case calculations. We also exclude SEER (Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, and Utah), NPCR-SEER (Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey), NPCR states with SEER metro areas (Georgia, Michigan, and Washington), and NPCR states with SEER metro and regional coverage (California) from this study. Shading denotes case volume (low, medium, and high). Patterns denote federal funding sources in place at the time this study began (2009).

We calculate consolidation effort, which is a routine activity performed by all registries, by dividing the number of cases reported by the number of records received and then subtracting that ratio from 1. A single incidence case may have several records attached to it, requiring consolidation to eliminate duplicate records and retention of additional information. Consolidating many records to fewer cases will require more effort and, therefore, may affect registry efficiency.

Other characteristics that may potentially affect registry efficiency include the following: the portion of cases from reporting sources that pass automatic edits; whether a registry has a major contractor who carries out all or a significant portion of the registry's operations; the portion of records that the registry receives via electronic submissions; and North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) Certification status (http://www.naaccr.org/Certification/CertificationLevels.aspx). Automatic edits and electronic submissions could require less effort for case reporting, resulting in a lower cost per case as the percentage of records or cases meeting these criteria increase. NAACCR Certification is awarded on the basis of the completeness, accuracy, and timeliness of the data submitted by registries and, therefore, an important measure of the quality achieved by the registries. Gold or silver status may reflect other unmeasurable registry characteristics that could affect efficiency of registry operations.

Program exclusion criteria

On the basis of consultations with registry experts and preliminary data analysis, we excluded SEER registries (fully or partially funded) from this analysis. Because we are analyzing registry-level data, we excluded these observations from our regression model to avoid unmeasured differences between these registries and the other NPCR registries. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries are required to collect and report more detailed information than NPCR registries; this fundamental difference in registry operations cannot be adequately addressed, nor controlled for in multivariate analysis. In addition, we also excluded the Pacific Regional Central Cancer Registry as CDC awarded the first cooperative agreement only in 2007, and this registry was not fully operational during the data collection period.

Multivariable regression specification

Multivariate analysis was used to assess the factors affecting the cost per case reported by NPCR-funded central cancer registries. We have used the log transformation of the dependent variable, cost per case, to account for the skewness in the distribution of the cost across the registries. We estimated the following equation by using a random-effects model:

where Y is a dependent variable (ie, log of total cost per case reported); X is a vector of registry characteristics; R is a vector of other factors that may affect registry operations; u is the between-entity error term; and ε is the within-entity error term.

Random-effects models allow for estimation of time-invariant variables given that certain registry characteristics do not vary across the 3 years of panel data used in this analysis. We performed a Hausman test to confirm that a random-effects model is appropriate for our analyses.14 Registry characteristics include geographic area, region, population size, case volume, and case consolidation effort. Other factors included in our regression analysis are the percentage of cases received that pass 100% edits and the percentage of records that are submitted electronically. We generated correlation coefficients for all potential variables to avoid multi-collinearity. We used a forced-in stepwise regression approach when developing the model to determine those factors that had a clear effect on cost per case. Although the summary statistics presented below (see discussion of Table 1) include additional variables, the regression model includes only the variables noted previously. All regression analyses and statistical tests of the model were performed by using the Stata statistical package, version 12.0.14

Table 1. Cancer Registry Characteristics, National Program of Cancer Registries.

| NPCR Registries (n = 40)a,b | |

|---|---|

| Case volume | |

| Low (<10 000 cases) | 32.5% |

| Medium (10 000-50 000 cases) | 50.8% |

| High (>50 000 cases) | 16.7% |

| Consolidation effort | |

| Low (<22%) | 28.3% |

| Medium (22%-33%) | 44.2% |

| High (>33%) | 27.5% |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 16.7% |

| South | 38.3% |

| Midwest | 25.0% |

| West | 20.0% |

| Geographic area | |

| Small (<42 000 square miles) | 36.7% |

| Medium (42 000-69 000 square miles) | 30.8% |

| Large (>69 000 square miles) | 32.5% |

| Population | |

| Low (<2.8 million) | 37.5% |

| Medium (2.8-6 million) | 35.4% |

| High (>6 million) | 27.1% |

| Other characteristics | |

| Cases passing 100% edits | 52.8% |

| Records submitted electronically | 80.6% |

| Major contractor | 20.0% |

| NAACCR gold status (2011) | 77.5% |

| NAACCR silver status (2011) | 7.5% |

Abbreviations: NAACCR, North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; NPCR, National Program of Cancer Registries.

Excludes the Pacific Regional Central Cancer Registry. Registry did not report cases diagnosed in 2006 and is still ramping up case reporting. Low case volume distorts cost per case calculations.

Excludes NPCR registries that also receive SEER funding: California (San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles), Georgia (Atlanta), Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan (Detroit), New Jersey, and Washington (Seattle-Puget Sound).

Results

Table 1 presents data about several registry characteristics and other factors, including those controlled for in our regression analyses. The largest proportion of the 40 registries included in our analyses were located in the South. Population size and geographic area were fairly evenly distributed. Half of the registries in our sample were programs with medium case volume. The majority of registries also reported medium consolidation effort. Twenty percent of registries had a major contractor who carried out all or a significant portion of the registry's operations. Many of the registries achieved NAACCR gold or silver status in 2011.

Table 2 presents average registry funding and the source of the funding for each reporting year for the 40 study registries. On average, nearly 61% of total registry funding came from NPCR. Nearly 39% of registry funding was from nonfederal sources, whereas less than 1% of registry funds came from other federal sources. The average amount of total funding for each central cancer registry was $1 154 474. Of this amount, $700 998 were NPCR funds, $9021 were other federal funds, and $444 455 were nonfederal funds. Table 2 also presents the distribution of registry expenditures and the cost per case of core and advanced activities for each reporting period and averaged across the 3 years. The majority of registry funds, approximately 93%, were spent on core registry activities. The average cost per case across 3 years of data collected was $60.77 for all activities; $56.52 for core registry activities, and was $4.25 for advanced registry activities.

Table 2. Funding by Source and Distribution of Expenditure on Core and Advanced Registry Activities by Fiscal Year, National Program of Cancer Registries.

| NPCR Registries (n =40)a,b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | Average | |

| Funding amount ($) | ||||

| Total funding received | 1 147 004 | 1 149 302 | 1 167 118 | 1 154 475 |

| Share of funding (%) | ||||

| NPCR | 59.56% | 60.34% | 62.23% | 60.71% |

| Other federal funds | 1.17% | 0.70% | 0.48% | 0.78% |

| Nonfederal funds | 39.27% | 38.96% | 37.29% | 38.51% |

| Registry activities (%) | ||||

| Core | 93.41% | 92.57% | 93.07% | 93.01% |

| Advanced | 6.59% | 7.43% | 6.93% | 6.99% |

| Cost per case ($) | ||||

| Core | $54.19 | $57.08 | $58.30 | $56.52 |

| Advanced | $3.82 | $4.58 | $4.34 | $4.25 |

| All activities (total) | $58.01 | $61.66 | $62.64 | $60.77 |

Abbreviation:NPCR, National Program of Cancer Registries.

Excludes the Pacific Regional Central Cancer Registry. Registry did not report cases diagnosed in 2006 and is still ramping up case reporting. Low case volume distorts cost per case calculations.

Excludes NPCR registries that also receive Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results funding: California (San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles), Georgia (Atlanta), Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan (Detroit), New Jersey, and Washington (Seattle-Puget Sound).

Table 3 presents the random-effects estimates of regionally adjusted cost per case by using a longitudinal (panel) data set containing 3 years of data for 40 NPCR registries. Note that cost per case is measured in logs to adjust for skewness in the variable. Higher case volume results in significantly lower cost per case, although there is little additional cost reduction for high volume relative to medium case volume (66% vs 54% lower for high and medium volume, respectively, compared to low volume). Even after adjusting for regional differences in employment costs, registries in the Midwest and West have a lower cost per case relative to registries in the South (73% and 30% lower per case, respectively). High consolidation effort (relative to low effort) increases cost per case (32%). As the percentage of records passing all automatic edits increases, cost per case decreases. The same holds true for the percent of records submitted electronically.

Table 3. Cost per Incident Cancer Case Reported, Adjusted for Regional Cost of Living, National Program of Cancer Registries.

| Dependent Variable | Cost per Case—All Activitiesa,b,c | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Independent Variablesd (Comparator in Italics) | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|

| |||

| Estimate | Lower | Higher | |

| Case volume (reference: low) | … | ||

| Medium case volume | −0.782e | −0.853 | −0.711 |

| High case volume | −1.073e | −1.202 | −0.944 |

| Consolidation effort (reference: low) | … | ||

| Medium consolidation effort | −0.029 | −0.161 | 0.220 |

| High consolidation effort | 0.275f | 0.019 | 0.531 |

| Region (reference: South) | … | ||

| Northeast | −0.086 | −0.309 | 0.137 |

| Midwest | −0.552e | −0.656 | −0.449 |

| West | −0.357e | −0.444 | −0.271 |

| Geographic area (reference: small) | … | ||

| Medium geographic area | 0.020 | −0.087 | 0.126 |

| Large geographic area | 0.366e | 0.189 | 0.542 |

| % of records passing 100% edits | −0.098e | −0.105 | −0.092 |

| % of records submitted electronically | −0.493e | −0.773 | −0.213 |

| Constant | 4.963 | ||

| Number of observations | 120.00 | ||

Abbreviation: NPCR, National Program of Cancer Registries.

Excludes the Pacific Regional Central Cancer Registry. Registry did not report cases diagnosed in 2006 and is still ramping up case reporting. Low case volume distorts cost per case calculations.

Excludes NPCR registries that also receive Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results funding: California (San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles), Georgia (Atlanta), Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan (Detroit), New Jersey, and Washington (Seattle-Puget Sound).

Cost per case adjusted using area wage index as noted in text previously. Log values are used.

Final model presented previously. R2 was 0.60 for this model. The following variables were dropped from the specification because of limited explanatory power or correlation between regressors: population size flags (low, medium, high); contractor flag; and North American Association of Central Cancer Registries status (gold or silver).

.001%; robust standard errors.

.05%; robust standard errors.

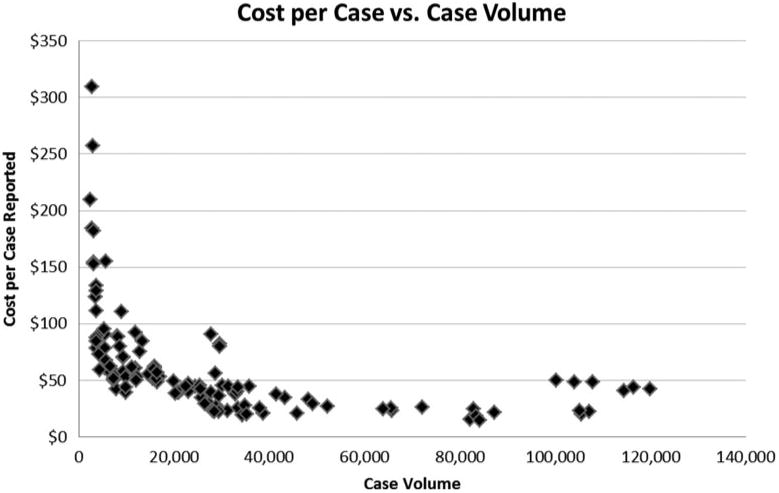

Figure 2 presents the unadjusted distribution of cost per case-by-case volume for all 3 years of data. As case volume increased, cost per case reported tended to decrease as revealed in the multivariate analysis presented in Table 3. The shape of the potential curve connecting the points on the graph is an inverse exponential distribution. There is a wide distribution in cost per case among low-volume registries, those under 10 000 cases, ranging from $40 per case to $310 per case. Larger registries, those that report more than 30 000 cases, all consistently have cost per case of about $50 or lower. Although registries with the highest volume seem to report costs close to $50 per case, there is no systematic evidence indicating diseconomies of scale given the current volume of distribution of cancer case registrations.

Figure 2.

Cost Per Case by Volume of Incident Cancer Cases Reported by Cancer Registries, National Program of Cancer Registries (Years 2009, 2010, and 2011)

Discussion

We analyzed 3 years of cost data reported by 40 central cancer registries funded by the NPCR. We saw little variation in the proportion of funding from different funding sources and in the average distribution of expenditures between core and advanced registry activities across the 3 years of data. The average cost per cancer case reported was about $61, but there was variation across registries. Receipt of high-quality data (as measured by the percentage of records passing automated edits), electronic reporting, and processing large volume of cases all result in significantly lower cost per case. We also identified some regional variation, with registries in the Midwest and West reporting lower costs on average.

The volume of cases reported has a large effect, indicating that there are economies of scale to be achieved as the cost per case significantly decreases with larger volume of cancer cases reported. This also indicates that there are potentially substantially fixed or semivariable costs associated with registry activities. These fixed costs can relate to facilities and other infrastructure required for data processing and reporting. Therefore, sharing of fixed costs among small volume contiguous state registries, whenever possible, and centralization of certain processes, may help reduce the overall average cost of cancer registration. Some state laws preclude the sharing of identifiable cancer registry data, but registries can develop innovative processes to consolidate efforts and still comply with state policies.

In addition, there is not a large difference in cost per case between medium- and high-volume registries, which leads to the conclusion that once registries reach a certain size (about 30 000 cases), there is not much additional economies of scale to be gained. There was large variation in the unadjusted cost per case among low-volume registries, which could indicate that there may be additional lessons to be learned by reviewing low-volume registries that may be efficient or may receive better-quality data that allows them to incur lower costs. We plan to explore the reasons for this variation in cost among low-volume registries in the next series of analyses planned for the economic evaluation of the NPCR registries.

The present research updates the prior work on assessing variation in cost across NPCR-funded cancer registries.5 We used more recent years of data and a more in-depth approach to collect activity-based costs, which focused on assessing all costs regardless of funding source. The prior research5 concluded that cost per case was inversely affected by volume of cancer cases reported, and that size of area served by the registry was positively associated with higher cost. In the present study, area served was not statistically significant, which could reflect shifts in data abstraction and reporting from a more manual process to a larger role of electronic reporting.6 In our sample, about 80% of the registries received a majority of their records electronically, indicating widespread use of electronic reporting. The process of moving away from manual abstraction could substantially decrease travel and staff time, and this could be the reason for the lack of significance of area served in this updated analysis.

Our results indicate that although a key driver of cost per case is case volume, registries receiving high-quality data also have significantly lower cost per case. As health care providers move increasingly toward electronic medical records and an automated process of reporting cancer incidence, there is opportunity for the quality of data received by the cancer registries to improve (only half the registries receive cases that pass 100% of electronic edits currently), and this could result in further efficiencies. Electronic reporting of cancer cases will increase in the near future, as it is a specific public health objective for Stage 2 Meaningful Use.15 Having a wide range of health care providers reporting to cancer registries should address current underreporting of certain cancers, such as melanoma and prostate cancer, which may be diagnosed and treated in physician's offices, and potentially reduce the work by cancer registry staff who collect and manage the data.

A potential limitation of the data analysis presented in this study is that the registries report data retrospectively, and the potential for recall error makes the reliability of retrospective data uncertain. A second limitation is the geographic diversity of the registries. The cost data were adjusted to account for regional variation, and we also included the 4 regions as additional control variables in the multivariable regression analysis. Differences between registries may persist despite these attempts to adjust for potential cost of living variations. A third limitation is reporting information about cancer cases, which involves data collection for each case that spans over several years. Therefore, although we used 3 years of data, there may still be a mismatch in aligning registry cost to the specific cases reported because of a lag in the reporting of cancer cases.8 A longer time period may be required to estimate the true cost of cancer registration. Fourth, additional approaches to assess quality of the data may be needed as there is little variation in the core measures used to assess quality of cancer registry data currently. Finally, although we were able to include all established registries funded by the NPCR, the overall sample size of the panel data of 40 registries and 3 years of data may not be large enough to capture all the potential differences between the registries.

This study's findings about the cost of operating cancer registries and factors that affect cost provide CDC and the registries with opportunities to identify cost savings and efficiency improvements. Additional processes to improve the quality of the data submitted to the cancer registries may improve efficiency, and the projected increase in electronic reporting of cancer incidence offers a unique opportunity to address data quality and efficiency. Furthermore, some consolidation and centralization of data collection and reporting processes, particularly among small-volume registries, may reduce the potential high fixed costs faced by cancer registries and decrease the overall cost of reporting a cancer case. Achieving efficiencies in cancer registry data collection is essential to ensure that high-quality data are available to guide the selection and implementation of future cancer prevention and control interventions.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding support for Sujha Subramanian, Maggie Cole Beebe, and Diana Trebino was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Contract No. 200-2002-00575, Task order 009, to RTI International).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Heron M. Death: leading causes for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(6):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2011 Incidence and Mortality Web-Based Report. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; [Accessed April 14, 2015]. www.cdc.gov/uscs. Published 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, Richardson LC, Howard D, Sabatino SA, Finkelstein EA. Cancer treatment cost in the United States: has the burden shifted over time? Cancer. 2010;116(14):3477–3484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard DH, Molinari NA, Thorpe KE. National estimates of medical costs incurred by nonelderly cancer patients. Cancer. 2004;100(5):883–891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weir HK, Berg GD, Mansley EC, Belloni KA. The National Program of Cancer Registries: explaining state variations in average cost per case reported. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(3):A10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramanian S, Green J, Tangka FK, Weir H, Michaud F, Ekwueme D. Economic assessment of central cancer registry operations. Part I: methods and conceptual framework. J Registry Manag. 2007;34(3):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramanian S, Tangka F, Green J, Weir H, Michaud F. Economic assessment of central cancer registry operations. Part II: developing and testing a cost assessment tool. J Registry Manag. 2009;36(2):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tangka F, Subramanian S, Beebe MC, Trebino D, Michaud F. Economic assessment of central cancer registry operations. Part III: results from five programs. J Registry Manag. 2010;37(4):152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French MT, Dunlap LJ, Zarkin GA, McGeary KA, McLellan AT. A structured instrument for estimating the economic cost of drug abuse treatment. The Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Program (DATCAP) J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;14(5):445–455. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson DW, Bowland BJ, Cartwright WS, Bassin G. Service-level costing of drug abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1998;15(3):201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salome HJ, French MT, Miller M, McLellan AT. Estimating the client costs of addiction treatment: first findings from the client drug abuse treatment cost analysis program (Client DATCAP) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71(2):195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed April 14, 2015];Employment cost index. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/eci.toc.htm. Published 2014.

- 13.US Census Bureau. [Accessed April 14, 2015];Geographic terms and concepts—census divisions and census regions. http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html.

- 14.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Public Health Objectives in Stage 2 Meaningful Use ONC and CMS Final Rules Version 1.1. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed April 14, 2015]. http://www.cdc.gov/ehrmeaningfuluse/Docs/Summary%20of%20PH%20Objectives%20in%20Stage%202%20MU%20ONC%20and%20CMS%20Final%20Rules.pdf. [Google Scholar]