Abstract

Nearly half of children with autism have eloped from their caregivers. In assessing elopement, the initial functional analytic results of this case study found positive reinforcement in the form of attention and access to tangibles were the maintaining variables. Functional communication training (FCT) in combination with delay fading was utilized to increase communication and decrease elopement. Results indicated that communication was consistent, elopement remained low, and the child learned to wait.

Keywords: Elopement, Autism, FCT, Delay fading

Elopement is defined as one person leaving a designated area without consent from a parent or caregiver and entering another area where the person’s safety and well-being is at stake (Lang et al. 2009; Tarbox et al. 2003). A child who breaks away from his mother’s grip at a traffic crosswalk, for instance, and sprints out into a busy street is risking injury and even death.

A recent report by Anderson et al. (2012) concluded that elopement is prevalent among children with autism. Nearly 50 % of this population has eloped from a parent or caregiver at least once by the age of 4 years, according to the report, and over one half of these children went missing long enough to cause concern over their safety.

One approach to treating elopement with children is Functional Communication Training or FCT (Carr and Durand 1985). The procedure begins with a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) (Iwata et al. 1982/1994) of the problem and progresses to teaching a child to access the reinforcer(s) identified in the FBA in a safer, more appropriate manner.

FCT research on elopement with a child whose behaviors show either or both an “attention” or “tangible” function, for example, involves teaching a child to access a favorite person or toy by making these stimuli contingent on an appropriate motor and/or verbal-vocal response (Falcomata et al. 2010; Lehardy et al. 2013; Perrin et al. 2008; Piazza et al. 1997; Tarbox et al. 2003). Examples of the approach include Piazza et al. (1997) and Tarbox et al. (2003), who taught individual children to touch or give a card to a tutor or to make a vocal response to access the relevant reinforcer. Increases in such communicative responding, according to these and similar studies, ordinarily produce corresponding decreases in elopement.

A second approach to treating elopement in children includes FCT with this addition: gradually lengthening the amount of time that elapses between the communicative response and the delivery of the relevant reinforcer. The practice is called delay fading (Schweitzer and Sulzer-Azaroff 1988).

Delay fading assumes that a child who elopes is displaying a low tolerance for a delayed reinforcer. The child who breaks his mother’s grip and runs into the street, on this view, cannot wait to get ahold of a toy in the store across the street. It follows that inserting progressively longer periods of time between an appropriate response (e.g., “Toy, please.”) and the delivery of the relevant reinforcer (the toy) would establish a higher tolerance for delayed reinforcement and lower the chances a child will elope.

Current examples of incorporating delay fading into FCT for elopement with children include Falcomata et al. (2010), Lehardy et al. (2013), and Luczynski and Hanley (2013). In one study, by Lehardy and his colleagues, an appropriate request (“Can I get something?”) produced the relevant reinforcer (a camera) without delay. The response to the child’s request on subsequent occasions (“You can get it but first you have to wait.”) signaled the start of a delay fading procedure whereby reinforcers were delivered on a fixed-interval (FI) schedule, contingent on waiting and no elopement.

A variable interval (VI) schedule seems better suited than FI for the practical purpose of delay fading. A VI schedule is convenient to use in applied settings because it does not require constant monitoring, and since the time interval is unpredictable, it better reflects the contingencies of delayed reinforcement in the natural environment. It also lends itself to the practice of schedule thinning (Hagopian et al. 2011), which naturally entails extending the delay to reinforcement.

We examined the feasibility of accomplishing delay fading with VI reinforcement within an FCT approach to elopement for a child with autism by using what is known technically as a conjunctive schedule (Ferster and Skinner 1957) with two components, a fixed-ratio 1 (FR 1) component and a VI component with progressively longer values.

Method

Participant and Setting

Damon, a 9-year-old boy diagnosed with autism, presented with a history of unlocking doors, running into streets and neighbors’ yards, and running from his parents while shopping. All sessions were conducted outside during walks throughout Damon’s neighborhood. The sessions were 10 min and were conducted three to five times a day, four to five times a week.

Response Definition and Measurement

Elopement was defined as moving more than 1 m away from the tutor in any direction. Communication was defined as appropriately requesting items or activities by making a verbal-vocal response (e.g., “Sand, please.”). Frequency data were collected by trained observers on the occurrence of elopement and appropriate requests.

Functional Analysis

The functional analysis (FA) was based on the procedures described by Tarbox et al. (2003). Because it would endanger the participant given the form of his elopement (running), an alone condition was not conducted. A tangible condition was added to determine whether elopement was maintained by access to items encountered along the walk (see below). Four FA conditions were assessed: attention, tangible, play, and demand. All sessions began with the tutor taking Damon’s hand and informing him they were going on a walk.

Contingent upon elopement during the attention condition, the tutor expressed concern (e.g., “I don’t like it when you walk away from me.”), provided a mild verbal reprimand (e.g., “Don’t run into the street.”), and briefly engaged in physical contact (e.g., touching the arm). For the tangible condition, Damon was given 30 s access to the item that he ran toward. There were times, however, when he could not access an item and his attempts were blocked. For example, if he ran toward a ball in a neighbor’s yard across the street, he was not given access to it. After accessing an item or activity, the tutor took Damon by the hand and continued walking. During the play condition, the tutor praised (e.g., “You’re walking great.”) and gently patted Damon on the back according to a fixed-time (FT) 30-s schedule.

For the demand condition, Damon was asked to reply to various questions throughout the walk (e.g., “What color is that car?”). If his response was appropriate (e.g., “Blue.”) and occurred within 3 s of the demand, praise was given by the tutor (e.g., “You’re right, it’s a blue car.”). A three-step prompt hierarchy with a 3-s delay between each step was used to assist Damon’s response to a demand. When eloping occurred, Damon was given a 30-s break from demands and walking. Walking and questioning resumed after the break.

FCT

Damon was taught to ask properly for relevant items and activities. This process involved stopping him when he eloped, returning him to the spot where elopement began, prompting a verbal-vocal request indicating what he wanted or wanted to do, as needed, and providing brief social praise for complying to the instructions.

Delay Fading

Once Damon was requesting appropriately and eloping infrequently under FCT conditions, a conjunctive FR 1 VI schedule was introduced. Throughout these sessions, when Damon asked for an item or activity, the tutor said, “You have to wait for now, so let’s keep walking.” The VI schedule began timing at this moment, and the first appropriate request that Damon made after the interval elapsed produced the relevant item or activity.

As a conjunctive schedule, two contingencies were in effect, the FR 1 contingency that began the VI schedule, and the VI schedule itself, which reinforced the first request after the end of the interval. The value of the VI component progressed through various phases, when no elopement occurred for three consecutive sessions, from VI 15 s to VI 30 s, VI 45 s, VI 90 s, and finally, VI 300 s (Table 1 shows the values used to achieve the five VIs.)

Table 1.

VI schedule values and increments and progressions

| VI schedule | Increments (s) and progressions |

|---|---|

| VI 12 s | 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 15, 20, 35 |

| VI 30 s | 5, 10, 15, 30, 35, 40, 45, 60 |

| VI 45 s | 5, 10, 15, 30, 35, 40, 45, 60, 90, 120 |

| VI 90 s | 10, 15, 20, 60, 70, 75, 80, 90, 180, 300 |

| VI 300 s | 60, 150, 180, 300, 420, 490, 540 |

If Damon requested an item or activity that was unavailable, he was told, “You cannot have that right now, so let’s keep walking to see what else we can find.” All other interactions with Damon that did not involve asking for something were treated naturally.

Results and Discussion

Functional Analysis and Baseline

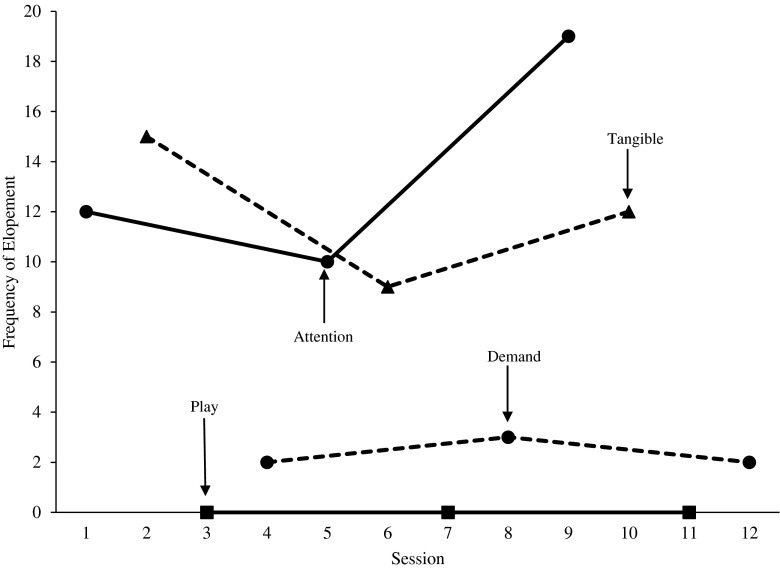

The FA results are shown in Fig. 1. Higher frequencies of elopement occurred during the attention and tangible conditions compared to the demand and play conditions, indicating that the primary functions of Damon’s elopement were the attention and the tangible items he received when he eloped.

Fig. 1.

Results of the functional analysis

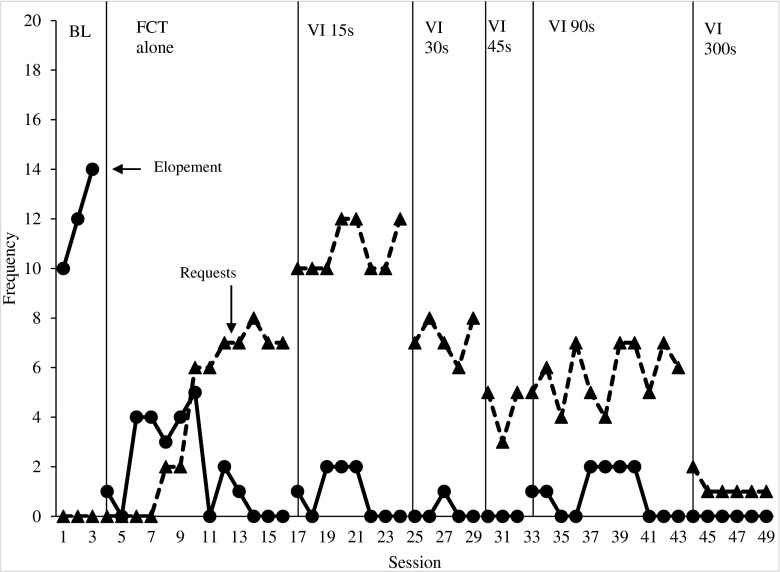

Given the results of the FA (see Fig. 1), baseline sessions were a mix of attention and tangible consequences. When Damon eloped, attention was given to him and he was permitted immediate access to the relevant item or activity for 30 s. As the first panel in Fig. 2 shows, elopement rose steadily, from 10 to 12 to 14 instances across the three baseline sessions, respectively. Damon made no relevant or appropriate verbal-vocal requests during baseline.

Fig. 2.

Baseline, FCT alone, and FCT with VI delay fading

FCT Alone

The results for FCT alone are shown in the second panel in Fig. 2. During this phase, the frequency of Damon’s requests increased steadily from zero to six to eight responses per session for the first half of the phase and stayed at this level throughout the last half of the phase. An increase in the frequency of elopements paralleled the increase in requesting; however, as Damon’s requests stabilized, the frequency of his eloping fell to zero and remained at that level for the rest of the phase.

Delay Fading + FCT

The third panel in Fig. 2 shows that delay fading began with the introduction of the conjunctive (FR 1 VI 15 s) schedule at session 17. The frequency of Damon’s requests rose to 10 per session and remained steady at 10–12 per session throughout this phase. A small increase in the frequency of elopements occurred during the first half of the phase but later fell to zero during the last half of the phase.

The conjunctive (FR 1 VI 30 s) phase results are shown in the fourth panel in Fig. 2. The frequency of Damon’s requests fell from the immediately preceding phase to six to eight per session and remained stable at this level for the entire phase. With the one exception at session 27, Damon did not elope during the phase.

Shown in the fifth panel in Fig. 2 are the results for the conjunctive (FR 1 VI 45 s) phase. The number of Damon’s requests remained stable at six to eight per session throughout this short, three-session phase. Damon did not elope during this time.

The conjunctive (FR 1 VI 90 s) phase results are shown in the sixth panel in Fig. 2. The frequency of Damon’s requests remained steady at four to seven per session. A moderate increase in the number of elopements occurred during the first two thirds of this phase. No elopements occurred during the last third of the phase.

The conjunctive (FR 1 VI 300 s) phase results are shown in the last panel in Fig. 2. For the most part, Damon made just one request per session throughout this phase. He did not elope during the phase, which lasted six consecutive sessions, his longest period without eloping.

By itself, FCT reduced Damon’s elopement and increased how often he asked properly for what he wanted. With the addition of delay fading, however, he also learned to ask and then wait before he asked again for what he wanted without eloping. Delay fading extended the benefits accrued with FCT for Damon by creating new opportunities to reinforce instances of a broad and widely reinforced class of behavior, namely waiting calmly for a preferred, albeit delayed, reinforcer.

Delay fading was accomplished in the present study by gradually thinning a VI schedule along a range of values. Practitioners are accustomed to schedule thinning, so thinning a VI schedule to achieve the aim(s) of delay fading is straightforward. Instructing parents and caretakers to use delay fading and to follow a VI thinning schedule seems equally possible. In fact, Damon’s parents were taught to use delay fading after the study was completed. They reported no elopements and mostly proper requests on walks and during family outings.

Moving forward, one matter is to assess the short- and long-term effects of delay fading by itself, relative to FCT by itself, on elopement. A second matter concerns the role of functional analysis. Damon’s FA and subsequent baseline sessions revealed a mixed tangible and attention function for elopement, which is why FCT targeted asking properly both for attention and a tangible. With delay fading, Damon never eloped “for attention” as he had before, but he instead would now run, for example, toward a box of sand without looking back to see whether or not the tutor was attending to him. The delay fading sessions provided praise contingent on tolerating the delay and not eloping, which may have been a sufficient amount of attention for Damon. On the other hand, the function of eloping could have changed to tangible, perhaps as a function of delay fading. In any case, future work on this matter is warranted.

Footnotes

• Decreasing elopement with a child diagnosed with autism

• Utilizing functional communication training (FCT) to teach a child to request items/activities

• Implementing delay fading to increase delay to reinforcement

• Assessing and treating elopement in the natural environment

References

- Anderson C, Law JK, Daniels A, Rice C, Mandell DS, Hagopian L, Law PL. Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2012;130:870–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr EG, Durand VM. Reducing behavior problem through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:111–126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcomata TS, Roane HS, Feeney BJ, Stephenson KM. Assessment and treatment of elopement maintained by access to stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:513–517. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster CB, Skinner BF. Schedules of reinforcement. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Boelter EW, Jarmolowicz DP. Reinforcement schedule thinning following functional communication training: review and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2011;4:4. doi: 10.1007/BF03391770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, B.A., Dorsey, M.F., Slifer, K.J., Bauman K.E., & Richman, G.S. (1982/1994). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lang R, Rispoli M, Mackalicek W, White PJ, Kang S, Pierce N, Mulloy A, Fragale T, O’Reilly M, Sigafoos J, Lancioni G. Treatment of elopement in individuals with developmental disabilities: a systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30:670–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehardy RK, Lerman DC, Evans LM, O’Conner A, LeSage DL. A simplified methodology for identifying the function of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:256–270. doi: 10.1002/jaba.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczynski KC, Hanley GP. Prevention of problem behavior by teaching functional communication and self-control skills to preschoolers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:355–368. doi: 10.1002/jaba.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin CJ, Perrin SH, Hill EA, DiNovi K. Brief functional analysis and treatment of elopement in preschoolers with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23:87–95. doi: 10.1002/bin.256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza CC, Hanley GP, Bowman LG, Ruyter JM, Lindauer SE, Saiontz DM. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:653–672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer JB, Sulzer-Azaroff B. Self-control: teaching tolerance for delay in impulsive children. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1988;50:173–186. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox RSF, Wallace MD, Williams L. Assessment and treatment of elopement: a replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:239–244. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]