Abstract

Objectives

The efficacy of tocilizumab (TCZ), an anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, has not previously been evaluated in a population consisting exclusively of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

In a double-blind randomised controlled trial (FUNCTION), 1162 methotrexate (MTX)-naive patients with early progressive RA were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1) to one of four treatment groups: 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and placebo+MTX (comparator group). The primary outcome was remission according to Disease Activity Score using 28 joints (DAS28–erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) <2.6) at week 24. Radiographic and physical function outcomes were also evaluated. We report results through week 52.

Results

The intent-to-treat population included 1157 patients. Significantly more patients receiving 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX and 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo than receiving placebo+MTX achieved DAS28-ESR remission at week 24 (45% and 39% vs 15%; p<0.0001). The 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group also achieved significantly greater improvement in radiographic disease progression and physical function at week 52 than did patients treated with placebo+MTX (mean change from baseline in van der Heijde–modified total Sharp score, 0.08 vs 1.14 (p=0.0001); mean reduction in Health Assessment Disability Index, −0.81 vs −0.64 (p=0.0024)). In addition, the 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX groups demonstrated clinical efficacy that was at least as effective as MTX for these key secondary endpoints. Serious adverse events were similar among treatment groups. Adverse events resulting in premature withdrawal occurred in 20% of patients in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group.

Conclusions

TCZ is effective in combination with MTX and as monotherapy for the treatment of patients with early RA.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01007435

Keywords: Early Rheumatoid Arthritis, DMARDs (biologic), Methotrexate

Introduction

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) can achieve long-term beneficial clinical and radiographic outcomes with early, effective treatment.1–3 For those with severe RA and poor prognostic features (seropositivity, erosive disease, high disease activity), recommendations support early intensive treatment to achieve remission or low disease activity,4 5 thus maximising long-term benefits. This may include use of conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in combination or early initiation of a biological DMARD.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) plays a pivotal role in RA pathogenesis, and has been implicated in the development of systemic symptoms and local inflammation, pannus formation and bone resorption leading to joint damage.6 7 RA disease activity correlates with elevated IL-6 level and activity.7 8

Tocilizumab (TCZ), a humanised monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-6 receptor-α and inhibits IL-6–mediated pro-inflammatory signalling,9 has demonstrated efficacy and safety in the treatment of patients with RA.10–14 Four phase III trials have demonstrated the clinical benefit of combining TCZ with DMARDs in patients with RA with inadequate responses to DMARDs (including antitumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents).10 12–14 Three trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of TCZ monotherapy in patients with RA.11 15 16

The efficacy of inhibiting IL-6 signalling has not been evaluated previously in a population consisting exclusively of methotrexate (MTX)-naive patients with early RA. We present results from the primary analysis of the first 52 weeks of FUNCTION, a 2-year phase III trial evaluating clinical and radiographic efficacy and safety of TCZ, in combination with MTX and as monotherapy, in early RA.

Methods

Trial design

FUNCTION was a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group, phase III trial in which patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1) to 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo or placebo+MTX. The randomisation sequence was stratified by serological status (presence of rheumatoid factor (RF) and/or anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies) and by geographical region. TCZ or placebo was administered intravenously every 4 weeks. MTX/placebo was initiated at 7.5 mg/week (to accommodate local recommendations of some countries at the time of study design), and was increased to a maximum of 20 mg/week by week 8 in patients with ongoing swollen or tender joints.

The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent.

Patients

Adults (≥18 years) with moderate to severe active RA, classified according to revised 1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria,17 of ≤2 years’ duration who had not previously received MTX or biological agents were included. Patients with features of poor prognosis were enrolled: inclusion criteria included Disease Activity Score using 28 joints and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) >3.2, swollen joint count ≥4 (66 joint count), tender joint count ≥6 (68 joint count), ESR ≥28 mm/h or C reactive protein ≥1 mg/dl, positive RF or anti-CCP antibodies or one or more erosion of hands, wrists or feet attributable to RA based on a central radiographic reading. Before baseline, DMARDs were withdrawn for appropriate washout periods (see online supplementary appendix). Patients could continue treatment with oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or oral corticosteroids (≤10 mg/day prednisone or equivalent), provided the doses had been stable for at least 2 or 4 weeks before baseline, respectively, and remained stable throughout the study. Patients could withdraw from the study at any time for any reason. In addition, withdrawal was recommended for patients who had alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevations ≥3× the upper limit of normal (ULN) that was accompanied by total bilirubin >2× ULN; withdrawal was required for patients with ALT or AST elevations >5× ULN.

Endpoints

The proportion of patients achieving remission (DAS28-ESR <2.6) at week 24 was the primary endpoint. Key secondary endpoints included assessment of ACR response criteria, radiographic efficacy by the van der Heijde–modified total Sharp score (mTSS), quality of life using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) physical and mental component scores (PCS and MCS) and physical function assessment by the Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ-DI) score. Exploratory/post hoc analyses included evaluation of Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI <2.8) remission and ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) preliminary criteria for remission. Serum levels of TCZ were measured. Safety was evaluated by the frequency and severity of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of efficacy was performed on the intent-to-treat population (all randomly assigned patients who received at least one TCZ/placebo infusion). The safety population included all patients who received at least one TCZ/placebo infusion and had at least one post-dose safety assessment.

Overall, the study required 1128 patients (282 per arm) to provide 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 10% in DAS28-ESR remission (DAS28-ESR <2.6) rate in the primary comparison between 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX and placebo+MTX (assumed DAS28 remission rates were 26% and 16%, respectively, under the null hypothesis of no treatment difference) in a two-sided test with a 5% significance level. The study was not powered to detect differences between TCZ groups. The sample size was not inflated to account for withdrawals as the primary analysis implemented a non-responder imputation approach that accounted for withdrawals.

Primary and all secondary efficacy endpoints were evaluated sequentially in a fixed hierarchy of statistical testing (with prioritisation of the primary comparator group, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX) to reduce the occurrence of false-positive conclusions resulting from multiple testing (see online supplementary appendix table S1). For the primary endpoint and dichotomous response variables (eg, ACR responses), TCZ groups were compared with the placebo+MTX group using logistic regression, adjusted for stratification factors (serological status and region) within the model. Patients who withdrew or for whom a DAS28-ESR score or an ACR20/50/70 response could not be determined were considered non-responders.

Changes from baseline in radiographic scores at week 52 were compared between the TCZ and placebo+MTX groups using non-parametric Van Elteren analysis stratified by region and serological status using linear extrapolation for missing data. Other continuous variables (eg, HAQ-DI score) were analysed using analysis of covariance that included treatment group, baseline score and baseline stratification factors. Non-radiographic continuous endpoints used a combination of last-observation-carried-forward and no imputation for missing data.

Results

Patient population

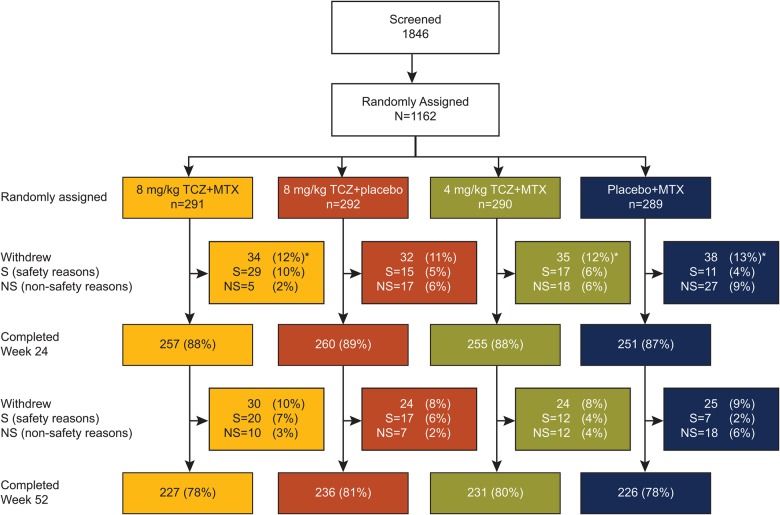

In total, 1162 patients were randomly assigned, and 920 (79%) completed 52 weeks of treatment; 96.1% of patients assigned to 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX or placebo+MTX achieved MTX doses of 15 mg/week or higher (see online supplementary appendix, results and tables S2–S4). Although overall withdrawal rates were similar among groups (figure 1), withdrawals in the placebo+MTX group were driven primarily by non-safety–related reasons (most notably insufficient therapeutic response and treatment refusal); withdrawals in the TCZ groups were driven primarily by safety (AEs, most notably laboratory abnormalities), with the highest incidence in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group, in which 47 of 291 patients (16.2%) experienced an AE that led to withdrawal (see Safety).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. *Five patients (two in the placebo+MTX group, two in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group and one in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group) did not receive study treatment and were excluded from analysis populations. Withdrawals in the placebo+MTX group were mainly driven by insufficient therapeutic response and refused treatment; withdrawals in the TCZ combination therapy groups were mainly related to safety (primarily hepatic transaminase elevations). Two patients randomly assigned to the placebo+MTX group received TCZ at the baseline visit and were allocated to the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group for safety analysis. The ITT population comprised 1157 patients, and the safety population comprised 1153 patients. ITT, intent-to-treat; MTX, methotrexate; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were balanced among treatment groups (table 1). Overall, patients had very early RA (mean duration, 0.4–0.5 years) with little radiographic damage at baseline (mean mTSS score, 5.66–7.72). Most patients were also RF or anti-CCP antibody positive (89%–91% and 86%–87%, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics (ITT population)

| Placebo+MTX n=287 |

4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX n=288 |

8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX n=290 |

8 mg/kg TCZ +placebo n=292 |

Missing values (all groups), n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 229 (80) | 228 (79) | 228 (79) | 219 (75) | 0 |

| Age, years | 49.6±13.10 (50.0) | 51.2±13.84 (53.0) | 49.5±13.70 (50.5) | 49.9±13.22 (51.0) | 0 |

| Duration of RA, years | 0.4±0.48 (0.2) | 0.4±0.49 (0.2) | 0.5±0.53 (0.3) | 0.5±0.48 (0.2) | 0 |

| DMARD naive, n (%)* | 228/282 (80.9) | 236/289 (81.7) | 230/290 (79.3) | 223/292 (76.4) | 4 |

| Number of previous DMARDs† | 0.2±0.41 (0.0) | 0.2±0.41 (0.0) | 0.2±0.49 (0.0) | 0.3±0.52 (0.0) | 0 |

| 0, n (%) | 228 (80.9) | 236 (81.7) | 230 (79.3) | 223 (76.4) | – |

| 1, n (%) | 53 (18.8) | 51 (17.6) | 53 (18.3) | 60 (20.5) | – |

| 2, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 6 (2.1) | 8 (2.7) | – |

| 3, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | – |

| Receiving corticosteroids, n (%) | 109 (38) | 107 (37) | 95 (33) | 118 (40) | 0 |

| RF positive, n (%) | 254 (89) | 255 (89) | 264 (91) | 262‡ (90) | 1 |

| Anti-CCP antibody positive, n (%) | 246 (86) | 245§ (86) | 252 (87) | 247 (86) | 6 |

| DAS28-ESR | 6.6±0.99 (6.5) | 6.7±1.05 (6.7) | 6.7±1.11 (6.8) | 6.7±0.99 (6.7) | 0 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 2.31±2.667 (1.28) | 2.59±3.053 (1.58) | 2.58±2.978 (1.69) | 2.48±3.186 (1.26) | 0 |

| ESR, mm/h | 50.4±26.81 (44.0) | 55.7±30.62 (48.0) | 52.8±30.15 (46.0) | 51.3±28.39 (41.5) | 0 |

| Tender joint count (68 joints) |

27.4±16.54 (23.0) | 28.1±15.63 (25.0) | 28.7±16.74 (24.5) | 28.7±16.33 (25.0) | 0 |

| Swollen joint count (66 joints) |

16.2±10.44 (13.0) | 16.1±10.16 (13.0) | 17.6±12.38 (14.0) | 16.5±10.10 (13.0) | 0 |

| HAQ-DI score | 1.48±0.665 (1.50) | 1.62±0.662 (1.75) | 1.50±0.625 (1.50) | 1.58±0.672 (1.63) | 11 |

| Patient pain VAS | 59.8±22.02 (62.0) | 59.5±22.62 (61.0) | 61.6±22.10 (65.0) | 62.5±21.82 (65.0) | 4 |

| Physician VAS | 62.7±17.27 (65.0) | 62.4±17.03 (63.0) | 63.6±18.12 (65.0) | 63.9±18.09 (65.0) | 0 |

| Patient global VAS | 63.8±21.51 (66.0) | 65.3±22.50 (66.0) | 66.5±21.46 (70.0) | 67.5±22.39 (71.0) | 0 |

| mTSS | 5.66±14.581 (1.50) | 7.72±17.155 (2.00) | 6.17±11.078 (2.00) | 6.85±16.100 (1.50) | 4 |

| JSN score | 2.34±7.452 (0.00) | 3.60±9.600 (0.00) | 2.67±6.488 (0.00) | 3.00±8.598 (0.00) | 4 |

| Erosion score | 3.32±7.642 (1.00) | 4.13±8.510 (1.50) | 3.49±5.722 (1.50) | 3.85±8.299 (1.00) | 4 |

Data are presented as mean±SD (median) unless stated otherwise.

*Reported for the safety population. Note: all patients were MTX naive per protocol.

†Rates of previous DMARD use included for placebo+MTX, 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX and 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo, respectively, are as follows: hydroxychloroquine, 7%, 4%, 8% and 10%; chloroquine, 4%, 3%, 3% and 4%; sulfasalazine, 6%, 9%, 10% and 9%; leflunomide, 2%, 1%, 1% and 3%; azathioprine, 0%, 0%, 1% and 1%; gold, 0%, <1%, 0% and <1%; and penicillamine, 0%, 0%, <1% and 0%.

‡Based on 291 patients.

§Based on 286 patients.

CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CRP, C reactive protein; DAS28, Disease Activity Score using 28 joints; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index; ITT, intent-to-treat; JSN, joint space narrowing; mTSS, modified total Sharp score; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; TCZ, tocilizumab; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Efficacy

Signs and symptoms

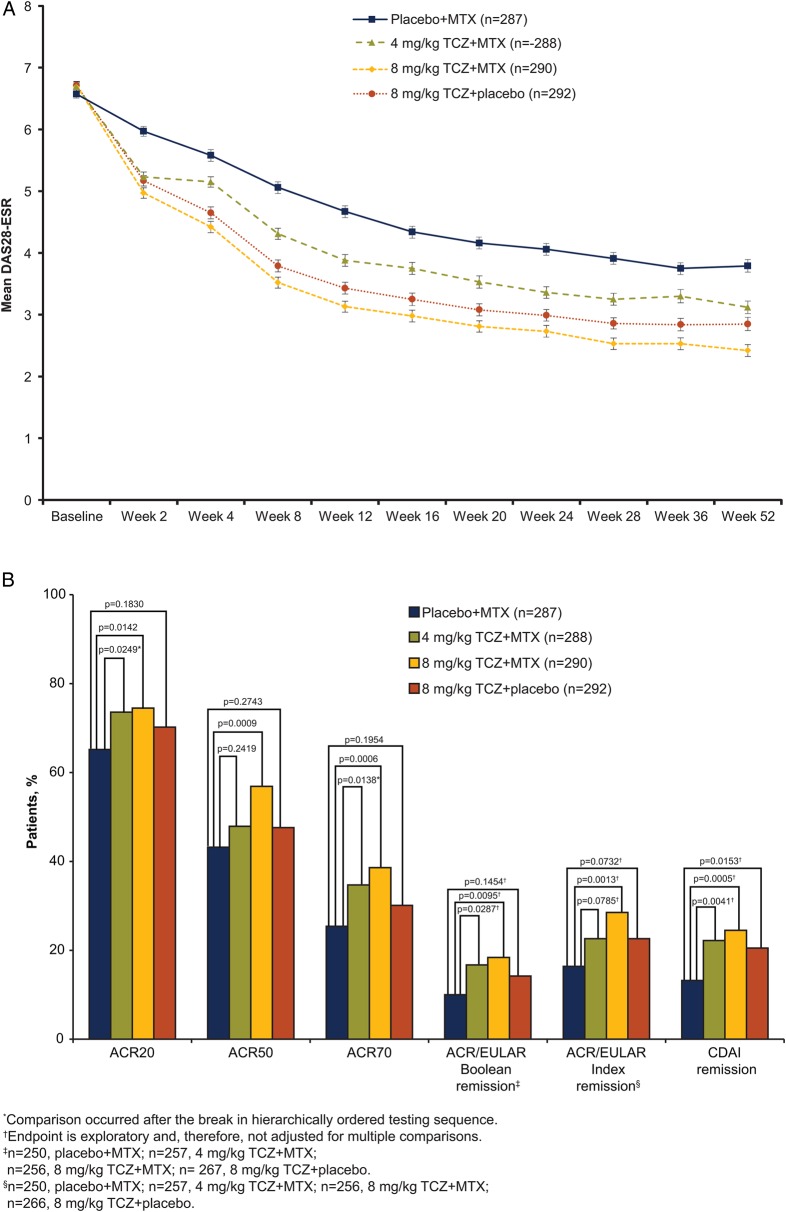

The primary endpoint was met: statistically significantly more patients achieved DAS28-ESR remission at weeks 24 and 52 with 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX than with placebo+MTX (45% vs 15% and 49% vs 20%, respectively; p<0.0001; table 2; OR, 24-week analysis, 4.77; p<0.0001). Significantly more 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo than placebo+MTX patients achieved DAS28-ESR remission at week 24 (39% vs 15%; p<0.0001). Results from sensitivity analyses were consistent with those of the primary analysis (see online supplementary appendix, results and table S5). Mean DAS28-ESR scores decreased over time to week 52 in all groups; the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group consistently showed the greatest decrease from baseline (figure 2A) and the lowest mean scores.

Table 2.

Proportions of patients achieving DAS28-ESR remission at week 24 and week 52

| Placebo+MTX n=287 |

4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX n=288 |

8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX n=290 |

8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo n=292 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 24 | ||||

| Responders, n (%) (95% CI) |

43 (15.0) (10.9 to 19.1) |

92 (31.9) (26.6 to 37.3) |

130 (44.8) (39.1 to 50.6) |

113 (38.7) (33.1 to 44.3) |

| p Value vs placebo+MTX | <0.0001* | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| OR (95%) relative to placebo+MTX | 2.72 (1.80 to 4.11) p<0.0001* |

4.77 (3.19 to 7.14) p<0.0001 |

3.70 (2.47 to 5.55) p<0.0001 |

|

| Week 52 | ||||

| Responders, n (%) (95% CI) |

56 (19.5) (14.9 to 24.1) |

98 (34.0) (28.6 to 39.5) |

142 (49.0) (43.2 to 54.7) |

115 (39.4) (33.8 to 45.0) |

| p Value vs placebo+MTX | <0.0001* | <0.0001 | <0.0001* | |

ORs were determined by logistic regression analysis.

*The comparison occurred after a break in the hierarchically ordered testing sequence.

DAS28, Disease Activity Score using 28 joints; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MTX, methotrexate; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Figure 2.

Efficacy endpoints (A) DAS28-ESR over 52 weeks. Mean DAS28-ESR scores by visit. Error bars show SEM (ITT population). (B) Secondary and exploratory endpoints at week 24. (C) Secondary and exploratory endpoints at week 52. (D) Change from baseline in HAQ-DI. All post-withdrawal efficacy data were excluded from analyses. Boolean criteria for ACR/EULAR remission require that the following be satisfied at the same visit: tender joint count (68) ≤1, swollen joint count (66) ≤1, Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (cm) ≤1, C-reactive protein ≤1 mg/dL. The index-based definition of ACR/EULAR remission is an SDAI score ≤3.3. SDAI is defined as the sum of tender joint count (28), swollen joint count (28), Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (cm), Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity (cm) and C-reactive protein (mg/dL). ACR endpoints used non-responder imputation; CDAI used LOCF for missing data; ACR/EULAR and HAQ-DI used no imputation for missing data. ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28, Disease Activity Score using 28 joints; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index; ITT, intent-to-treat; LOCF, last-observation-carried-forward; MTX, methotrexate; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Significantly greater response rates were also observed for 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX versus placebo+MTX for ACR20/50/70 responses at weeks 24 and 52 (p≤0.0142; figure 2B,C). DAS28-ESR remission and ACR response rates indicated improvement in RA signs and symptoms in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX groups at weeks 24 and 52 (table 2, figure 2B, C). A non-significant result in the statistical testing hierarchy (see online supplementary appendix table S1) occurred at the comparison of week 24 ACR50 response between 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and placebo+MTX (p=0.2743). Therefore, all endpoints subsequently tested in the hierarchical chain were considered non-significant. Improvements in SF-36 PCS and MCS were observed in all arms at weeks 24 and 52; the numerically greatest changes were with 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX (see online supplementary appendix figure S1). Analysis of ACR/EULAR Boolean and Index remission and CDAI remission demonstrated numerically higher remission rates with 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX than with placebo+MTX at week 24; however, as exploratory endpoints, these were not adjusted for multiplicity (figure 2B).

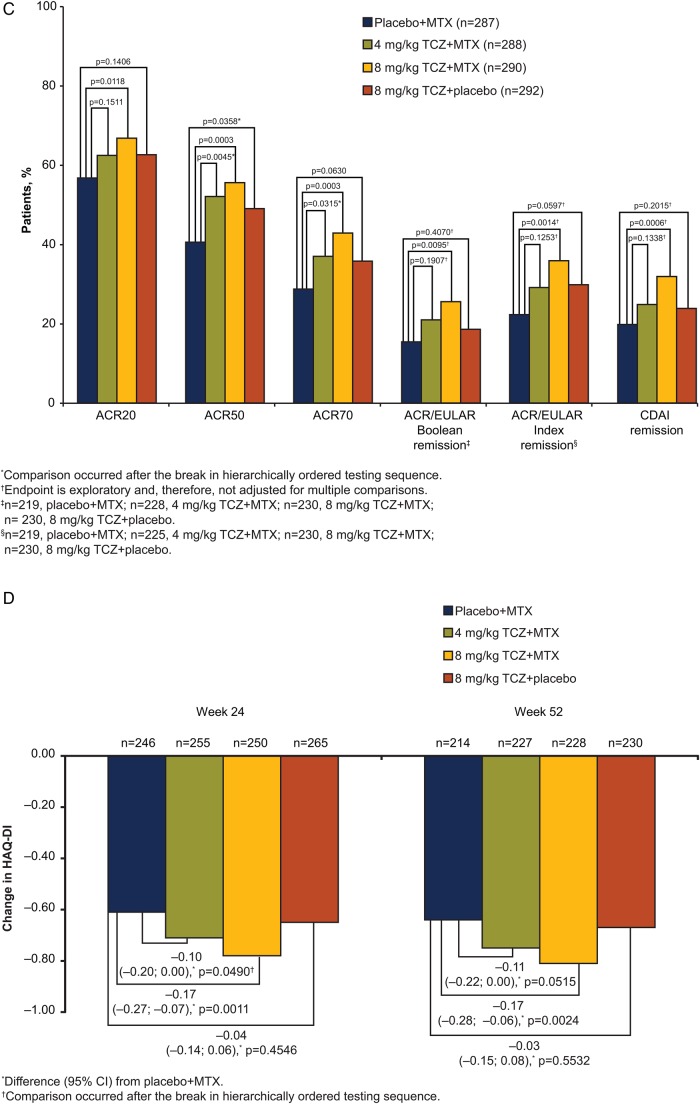

Radiographic

Compared with placebo+MTX, inhibition of joint damage was significantly greater with 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX (mean (SD) change in mTSS=0.08 (2.09) vs 1.14 (4.30); p=0.0001; figure 3A). Mean changes from baseline to week 52 in mTSS were smaller with 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX (mean (SD), 0.26 (1.88) and 0.42 (2.93), respectively) than with placebo+MTX (1.14 (4.30); figure 3A). Up to 83% of patients in all TCZ-treated groups showed no radiographic progression from baseline (change in mTSS ≤0) at weeks 24 and 52, whereas 73% in the placebo+MTX group showed no change (see online supplementary appendix figure S2). Mean change from baseline to week 52 in erosion and joint space narrowing scores followed a trend similar to that of the overall mTSS (figure 3A). Sensitivity analyses confirmed these findings (see online supplementary appendix figure S3). The cumulative distribution plot of change from baseline in mTSS at week 52 shows a shift to the right, indicating less progression of joint damage for the TCZ groups than for the placebo+MTX group (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of joint damage over 52 weeks. (A) Mean change in radiographic scores from baseline to week 52 (ITT population). Missing data were imputed using linear extrapolation. (B) Cumulative probability plot of change in mTSS from baseline based on radiographs taken at baseline, week 24, week 52 and withdrawal. Radiographic endpoints were analysed using a non-parametric Van Elteren analysis method. Because of the primary imputation method of linear extrapolation for patients with one baseline and one or more post-baseline radiographs, 93%, 93%, 94% and 94% of patients in the placebo+MTX group, the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group, the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group and the 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo group, respectively, contributed to the week 52 analysis. Linear extrapolation was used for 15% to 17% of patients across all treatment arms at week 52 (placebo+MTX group, 44/287; 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group, 44/288; 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group, 50/290; 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo group, 45/292). ITT, intent-to-treat; JSN, joint space narrowing; mTSS, van der Heijde–modified total Sharp score; MTX, methotrexate; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Physical function

Significantly greater improvements in mean HAQ-DI scores from baseline to week 52 were observed for 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX than for placebo+MTX (mean, −0.81 vs −0.64; difference (95% CI) from placebo+MTX, −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.06), p=0.0024; figure 2D). Both 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX showed improvements in HAQ-DI scores from baseline to week 52 (mean (difference from placebo+MTX; 95% CI), −0.67 (−0.03 to −0.15; 0.08) and −0.75 (−0.11 to −0.22; 0.00), respectively) at least equal to those of placebo+MTX (−0.64).

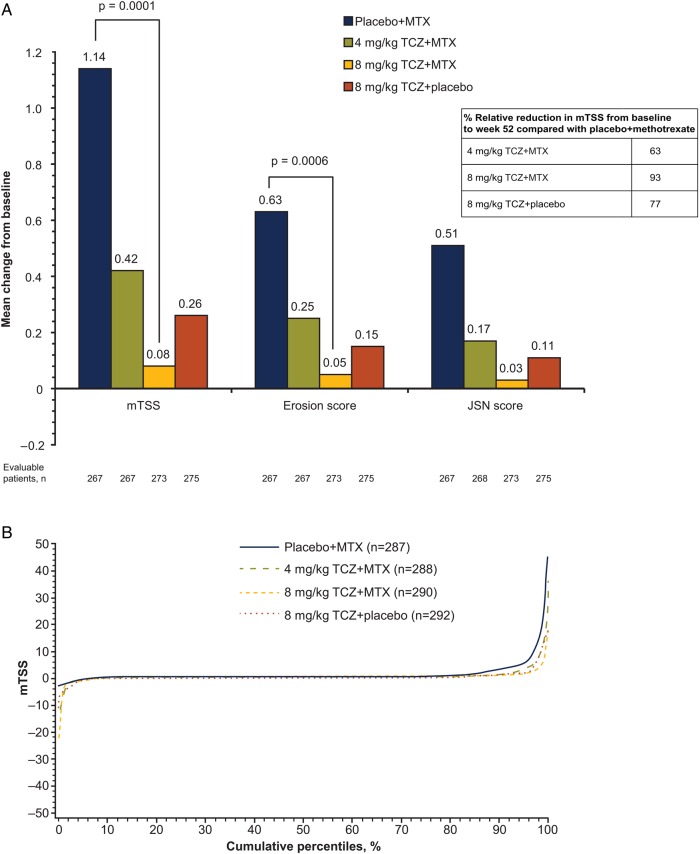

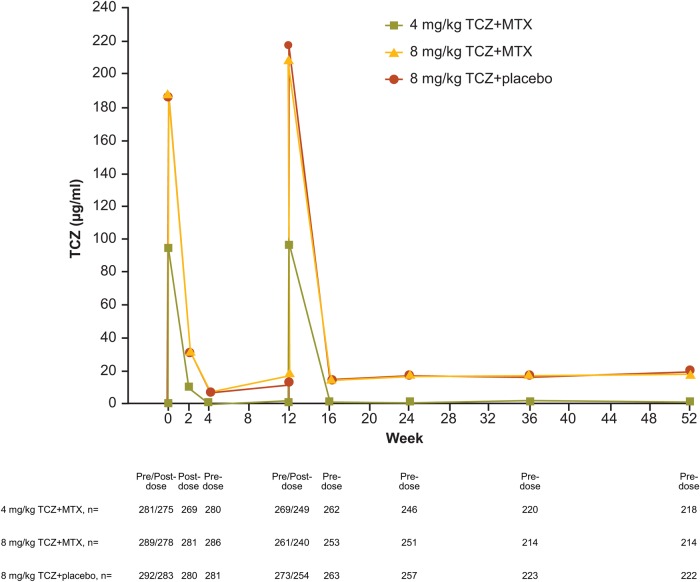

Serum levels

In patients for whom data were available, after the administration of study drug, serum concentration profiles of TCZ were similar with 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX and lower with 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean serum TCZ concentrations. MTX, methotrexate; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Safety

AEs/serious AEs (SAEs) were reported in 88.3%/10.7% of 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX patients, 85.6%/8.6% of 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo patients, 88.6%/10.0% of 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX patients and 83.3%/8.5% of placebo+MTX patients (table 3). AEs resulting in premature withdrawal occurred in 20.3% of 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX patients, 11.6% of 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo patients, 12.1% of 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX patients and 7.4% of placebo+MTX patients. In all TCZ treatment groups, the most common reasons for treatment discontinuation were attributed to the investigations system organ class, particularly events related to liver enzyme elevations (the most common preferred terms in TCZ groups were ALT increased (27 patients), transaminase increased (22 patients) and AST increased (4 patients)).

Table 3.

Summary of safety findings (safety population)

| Placebo+MTX n=282 |

4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX n=289 |

8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX n=290 |

8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo n=292 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with one or more event, n (%) | ||||

| Any AEs | 235 (83.3) | 256 (88.6) | 256 (88.3) | 250 (85.6) |

| Infections | 136 (48.2) | 155 (53.6) | 137 (47.2) | 138 (47.3) |

| AEs resulting in premature withdrawal from the study | 21 (7.4) | 35 (12.1) | 59 (20.3) | 34 (11.6) |

| Any SAEs | 24 (8.5) | 29 (10.0) | 31 (10.7) | 25 (8.6) |

| SAEs of special interest | ||||

| Infections | 6 (2.1) | 11 (3.8) | 10 (3.4) | 8 (2.7) |

| Malignancies | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.4) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) |

| Myocardial infarctions | 0 | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Strokes | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypersensitivity reactions | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Gastrointestinal perforations | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic events | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Deaths, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Clinical laboratory abnormalities | ||||

| Neutropenia | ||||

| Grade −3 (<1.0–0.5×109/L) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 10 (3.4) | 8 (2.7) |

| Grade −4 (<0.5×109/L) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Thrombocytopenia (based on platelet count) | ||||

| Grade −3 (<50–25×109/L) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Grade −4 (<25×109/L) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| ALT elevations | ||||

| Grade 1 (>ULN–2.5× ULN) | 120 (42.6) | 125 (43.3) | 136 (46.9) | 115 (39.4) |

| Grade 2 (>2.5–5× ULN) | 21 (7.4) | 35 (12.1) | 59 (20.3) | 19 (6.5) |

| Grade 3 (>5.0–20× ULN) | 3 (1.1) | 10 (3.5) | 10 (3.4) | 5 (1.7) |

| Grade 4 (>20× ULN) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AST elevations | ||||

| Grade 1 (>ULN–2.5× ULN) | 88 (31.2) | 95 (32.9) | 137 (47.2) | 86 (29.5) |

| Grade 2 (>2.5–5× ULN) | 11 (3.9) | 12 (4.2) | 18 (6.2) | 9 (3.1) |

| Grade 3 (>5.0–20× ULN) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.7) | 3 (1.0) |

| Grade 4 (>20× ULN) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

All values are n (%).

ALT ULN=55 U/L.

AST ULN=40 U/L.

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; MTX, methotrexate; SAE, serious adverse event; TCZ, tocilizumab; ULN, upper limit of normal.

The most frequently reported AEs and SAEs were infections; the percentage of infections was similar overall in the two 8 mg/kg TCZ groups and the placebo+MTX group and a numerically higher percentage of infections in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group (table 3). The most frequently reported serious infection was pneumonia, accounting for 12 of 35 serious infections. No opportunistic infections were reported. One newly diagnosed case of tuberculosis occurred in a patient in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group through close exposure to a relative with active tuberculosis.

Elevations in ALT concentrations according to the Common Toxicity Criteria (V.3.0; table 3) occurred most frequently in the TCZ+MTX groups, and were dose dependent: grade ≥2 elevations were seen in 15.6%, 23.8%, 8.2% and 8.5% of patients in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and placebo+MTX groups, respectively. No instances of grade 4 elevations were reported. Most elevations >3× the ULN in all treatment groups occurred at a single time point during the 52-week treatment period (8.3%, 8.3%, 4.5% and 4.6% with 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and placebo+MTX patients, respectively). No associations between neutropenia and serious infections or between thrombocytopenia and bleeding events were observed. Increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol from <160 mg/dL at baseline to ≥160 mg/dL were reported in 8.0%, 12.1%, 15.1% and 3.2% of 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX, 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and placebo+MTX patients, respectively.

Thirteen malignancies were reported (five before day 50); incidences were similar among all groups. Breast cancer was the most commonly reported malignancy (three patients; see online supplementary appendix table S6). Nine deaths occurred: two in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group, one in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo group, four in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group and two in the placebo+MTX group. The underlying cause of death varied across treatment groups (see online supplementary appendix table S7). Three of four deaths in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group were in patients who were older than 80 years.

Discussion

FUNCTION is the first trial to examine the effects of inhibiting IL-6 signalling as a first-line therapeutic option for RA. The study entry criteria specifically targeted patients with active disease and features of progressive disease (baseline mean DAS28-ESR ranged from 6.6 to 6.7; approximately 90% of enrolled patients were seropositive for RF and/or anti-CCP antibodies), which is the target population for whom early use of intensive therapy, such as with a biological agent, may be appropriate.5

Although the study was not powered to detect differences in treatment effects between the TCZ arms and all doses/regimens of TCZ demonstrated clinical benefit compared with MTX alone, the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group consistently achieved the best outcomes across all efficacy measures. For the duration of the 52-week study, the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX regimen (the primary comparator) significantly improved clinical outcomes and functional ability (measured by HAQ-DI score) and inhibited joint damage progression compared with the MTX-alone regimen. The primary endpoint was met: 45% of 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX patients achieved DAS28 remission at 24 weeks compared with 15% of placebo+MTX patients. Of interest, in contrast to the humanised monoclonal anti-TNF antibody adalimumab,18 the addition of MTX to TCZ did not result in TCZ serum levels significantly higher than levels attained with TCZ monotherapy. Although the underlying mechanisms that drive serum levels of a biological treatment in the context of combination with MTX versus monotherapy are not fully elucidated, our findings suggest that synergy between IL-6 inhibition and MTX action, rather than higher serum drug levels, drives the higher clinical response observed with TCZ+MTX. Exploratory analyses across other disease remission measures (ACR/EULAR Boolean and Index remission, CDAI remission), which were of clinical importance despite their not being validated in a clinical trial setting, also showed that improvement with 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX was at least equal to improvement with MTX alone. Analysis of CDAI remission is of particular interest because this composite disease activity measure does not include an acute-phase reactant, and it demonstrates that control of disease activity in TCZ-treated patients with early RA was independent of the direct pharmacodynamic effect of TCZ in suppressing the synthesis of acute-phase reactant proteins.19

Early radiographic progression contributes to long-term disability, and prevention of structural joint damage is an important therapeutic goal early in and throughout the course of the disease.20 21 Baseline radiographic joint damage was low in all treatment groups, reflecting the early stage of RA in the study population. This finding is consistent with other trials in early RA populations.1 22–24 Throughout 52 weeks, patients treated with TCZ experienced less radiographic progression than patients treated with MTX monotherapy, with the greatest joint damage inhibition in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group. Of note, mTSS progression was low overall, even in the comparator MTX monotherapy arm, as has been observed in other early RA trials.

The recommended starting dose for intravenous TCZ in the USA and Canada is 4 mg/kg,25 in contrast to 8 mg/kg used in the rest of the world; 8 mg/kg TCZ monotherapy has also demonstrated efficacy in patients with RA.11 15 16 Therefore, it was of interest to evaluate these TCZ dose regimens in the early RA population. Both 8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo and 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX achieved DAS28 and ACR efficacy responses consistently at least equal to those observed with placebo+MTX. These regimens also demonstrated suppression of radiographic structural joint damage, with 77% (8 mg/kg TCZ+placebo) and 63% (4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX) relative reduction in mTSS to week 52 compared with rates seen in the MTX+placebo group. Numerically greater inhibition in structural joint damage was observed with 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX than with 8 mg/kg TCZ monotherapy or 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX. Therefore, although 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX is the most effective treatment, both 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX and 8 mg/kg TCZ monotherapy represent good alternative treatments for subsets of patients, such as those unable to tolerate MTX or the higher 8 mg/kg dose because of contraindications or adverse reactions.

Several other biological agents have proven efficacy in the early RA population. Because of differences in study design, comparisons across trials are difficult. Nevertheless, TCZ appears to demonstrate benefits in patients with early RA (in regard to DAS28 remission, ACR responses and radiographic endpoints), compared with patients treated with MTX alone, that are generally consistent with those observed in previous studies of biological therapies in similar populations.1 3 22 26 Although a number of head-to-head comparison studies of different biological agents have recently been published,15 27 these have generally been performed in patients who have more established RA and who have responded inadequately to previous DMARDs. It would be of interest to conduct such studies in more treatment-naive patients with early RA.

AEs observed in the TCZ groups were consistent with the known safety profile of TCZ; no additional safety signals were observed, and the most frequently reported AE was infection in all TCZ groups and in the placebo+MTX group. However, a numerically higher incidence of certain events (infections, malignancies, myocardial infarctions and deaths) was reported in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group than the other groups. Although patients in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group were marginally older than the other patients, there were no imbalances in any other baseline demographic or disease characteristics. The significance of, and reason for, these small numerical differences are unclear. Changes in laboratory parameters (eg, increased hepatic transaminase levels and decreased neutrophil and platelet counts) have been reported for TCZ.10–14 Consistent with the known effects of TCZ and of MTX on transaminase levels, more patients in the TCZ+MTX groups than in either monotherapy group experienced ALT elevations, though AST elevations were similar between TCZ+MTX and TCZ monotherapy. Importantly, most elevations occurred at a single time point, were not sustained and did not result in any clinical sequelae (no serious hepatic events were reported). Thrombocytopenia was similar between TCZ+MTX and TCZ monotherapy groups. Consistent with intravenous TCZ dosing, one hypersensitivity reaction was reported in the 4 mg/kg TCZ+MTX group and one was reported in the TCZ monotherapy group. Rates of AEs resulting in premature withdrawal in this study ranged from 12% in the 4 mg/kg and TCZ monotherapy arms to 20% in the 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX arm; these proportions were higher than in previous studies of TCZ,10–14 which were conducted in more treatment-experienced populations. The higher withdrawal rates might have resulted from the protocol-mandated requirement for withdrawal in response to transaminase elevations (if three consecutive doses of intravenous study drug were missed because of transaminase elevations, the patient was withdrawn).

This study had some limitations. The blinded nature precluded dose modification of intravenous TCZ/placebo, MTX dose was limited to 20 mg/week and laboratory abnormalities were managed, according to protocol, by interruption or discontinuation of intravenous dosing. These conditions may not reflect actual clinical practice. Furthermore, it is unclear whether these results are generalisable to patients with early RA that is less severe.

Overall, the results of this study support the effectiveness and clinical benefit of TCZ in MTX-naive patients with early progressive RA. The greatest benefit was afforded by 8 mg/kg TCZ+MTX; the other TCZ regimens were at least as effective as MTX in improving signs and symptoms and physical function and in inhibiting joint damage. These results add to the body of evidence showing the efficacy of TCZ as therapy for patients with RA across several populations, including patients who respond inadequately to DMARDs12–14 16 or to anti-TNF agents10 and patients who receive TCZ monotherapy because MTX is contraindicated or cannot be tolerated.11 15 Further observation of these patients, for up to 2 years of blinded treatment, will investigate the maintenance of clinical (HAQ-DI) and radiographic outcomes and the long-term safety of TCZ in patients with early RA and poor prognostic features.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by the authors, with professional writing and editorial assistance provided by Sara Duggan, PhD, Karen Stauffer, PhD, Maribeth Bogush, PhD, and Meryl Mandle, who provided writing services on behalf of F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Revisions to the manuscript were performed by the authors, with professional writing and editorial assistance provided by Sara Duggan, PhD, and Meryl Mandle, on behalf of F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. The authors thank Emma Healy and Susanna Grzeschik of F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., who contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and data analyses and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

Footnotes

Contributors: GRB and WFR contributed to the conception and design of the study. GRB, WFR, RFvV, JK and AR-R contributed to data acquisition. GRB, WFR, RFvV, JK, AR-R, AK, SD and NM analysed and interpreted the data. NM conducted the literature search. GRB, WFR, JK, AK, SD and NM drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Roche. Funding for manuscript preparation was provided by F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Competing interests: GRB reports grants paid to his institution from Roche and personal fees for lectures and consulting from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer and UCB Pharma outside the submitted work. WFR reports grants and personal fees from Roche outside the submitted work. RFvV reports grants from the Karolinska University Hospital during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GSK, Pfizer, Roche and UCB Pharma outside the submitted work; and personal fees from Biotest, Janssen, Lilly, Merck and Vertex outside the submitted work. JK reports grants paid to his institution from Abbott Laboratories, Roche Laboratories and Sanofi-Aventis during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Amgen, Inc., AbbVie Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Eli Lilly and Company, Epirus Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., Genentech, Inc., Hospira, Inc., Janssen Biotech, Inc., Pfizer Inc, Roche Laboratories, Inc. and UCB Pharma outside the submitted work. AR-R reports grants from Chugai, Roche and Pfizer and honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche and UCB Pharma. AK is a full-time employee of Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. SD is a full-time employee of Roche Products Ltd. NM was a full-time employee of Roche Products Ltd. at the time this study was conducted.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Emery P, Breedveld F, van der Heijde D, et al. Two-year clinical and radiographic results with combination etanercept-methotrexate therapy versus monotherapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a two-year, double-blind, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:674–82. 10.1002/art.27268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Fleischmann RM, et al. Long-term safety, efficacy, and radiographic outcome with etanercept treatment in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:1232–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3432–43. 10.1002/art.20568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:625–39. 10.1002/acr.21641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayer JM, Choy E. Therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis: the interleukin-6 receptor. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:15–24. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houssiau FA, Devogelaer JP, Van Damme J, et al. Interleukin-6 in synovial fluid and serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:784–8. 10.1002/art.1780310614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottenberg JE, Dayer JM, Lukas C, et al. Serum IL-6 and IL-21 are associated with markers of B cell activation and structural progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the ESPOIR cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1243–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimoto N, Terao K, Mima T, et al. Mechanisms and pathologic significances in increase in serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor after administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Castleman disease. Blood 2008;112:3959–64. 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1516–23. 10.1136/ard.2008.092932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones G, Sebba A, Gu J, et al. Comparison of tocilizumab monotherapy versus methotrexate monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: the AMBITION study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:88–96. 10.1136/ard.2008.105197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371:987–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60453-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genovese MC, McKay JD, Nasonov EL, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab reduces disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: the tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2968–80. 10.1002/art.23940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kremer JM, Blanco R, Brzosko S, et al. Tocilizumab inhibits structural joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate responses to methotrexate: results from the double-blind treatment phase of a randomized placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab safety and prevention of structural joint damage at one year. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:609–21. 10.1002/art.30158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet 2013;381: 1541–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougados M, Kissel K, Sheeran T, et al. Adding tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab monotherapy in methotrexate inadequate responders: 24-week symptomatic and structural results of a 2 year randomized controlled strategy trial in rheumatoid arthritis (ACT-RAY). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:43–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1580–8. 10.1136/ard.2010.138461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burmester GR, Kivitz AJ, Kupper H, et al. Efficacy and safety of ascending methotrexate dose in combination with adalimumab: the randomised CONCERTO trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1037–44. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Peck R. Clinical pharmacology of tocilizumab for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2011;4:539–58. 10.1586/ecp.11.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindqvist E, Jonsson K, Saxne T, et al. Course of radiographic damage over 10 years in a cohort with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:611–16. 10.1136/ard.62.7.611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolfe F, Sharp JT. Radiographic outcome of recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a 19-year study of radiographic progression. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1571–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. 10.1002/art.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1870–7. 10.1136/ard.2008.101121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tak PP, Rigby WF, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Inhibition of joint damage and improved clinical outcomes with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: the IMAGE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:39–46. 10.1136/ard.2010.137703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genentech, Inc. ACTEMRA (tocilizumab) injection, for intravenous use injection, for subcutaneous use. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc., 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, et al. Golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneously every four weeks in methotrexate-naive patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: twenty-four-week results of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of golimumab before methotrexate as first-line therapy for early-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2272–83. 10.1002/art.24638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, et al. Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a phase IIIb, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65: 28–38. 10.1002/art.37711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.