Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in persons with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Specific risk factors associated with diabetes, such as hyperglycemia and kidney disease, have been demonstrated to increase the incidence and progression of CVD. Nevertheless, few data exist on the effects of traditional risk factors such as dyslipidemia, obesity and hypertension on CVD risk in youth with T1D. Improvements in understanding and approaches to the evaluation and management of CVD risk factors, specifically for young persons with T1D, are desirable. Recent advances in non-invasive techniques to detect early vascular damage, such as the evaluation of endothelial dysfunction and aortic or carotid intima media thickness, provide new tools to evaluate the progression of CVD in childhood. In the present review, current CVD risk factor management, challenges, and potential therapeutic interventions in youth with T1D are described.

Keywords: Diabetes type 1, cardiovascular, lifestyle, pediatrics

Introduction

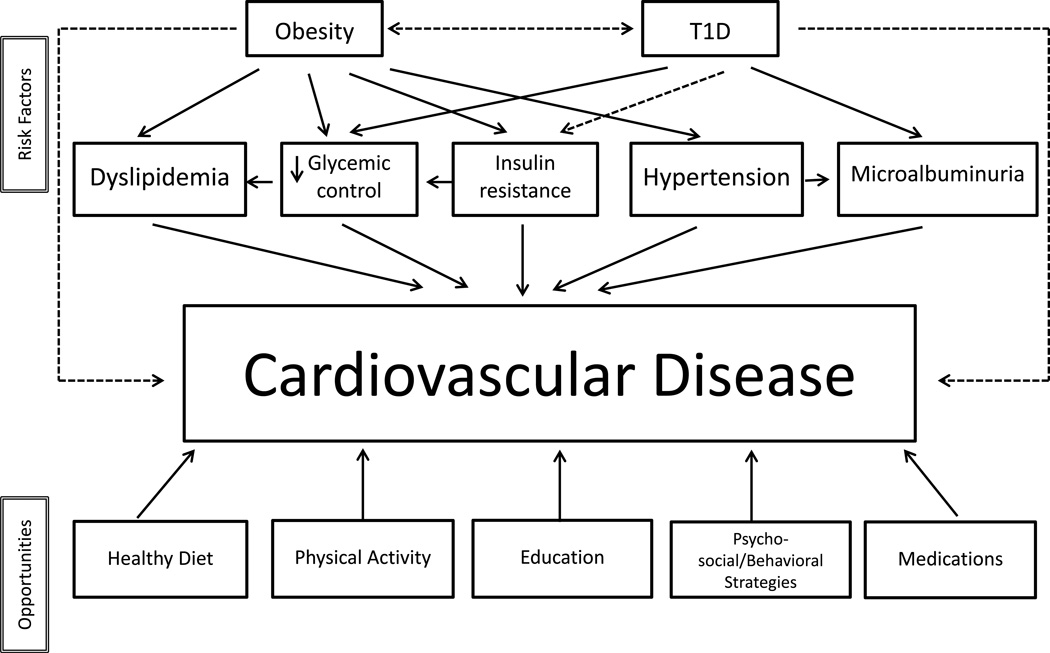

The incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in persons with type 1 diabetes (T1D) is substantially higher than in individuals without diabetes and is the leading cause of their morbidity and mortality [1,2]. In a large population study, the risk of death from CVD in persons with T1D with on-target glycemic control was more than twice the risk in the general population, and 10 times greater in subjects with poor glycemic control [3]. Even if coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral arterial disease become manifest only in adulthood, the process of atherosclerosis at the endothelial level begins early in T1D individuals [4,5]. Therefore, patients with T1D diagnosed during childhood are at especially high risk of developing premature CVD [6]. This review will focus on traditional risk factors for CVD in youth with T1D. The role of glycemic control, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and overweight/obesity in the pathogenesis of CVD in youth with T1D will be discussed as well as opportunities for interventions to reduce their impact (Figure 1). While smoking remains a potent CVD risk factor and should be avoided in all young persons, discussion of this risk factor is not included.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of risk factors and opportunities in the management of cardiovascular risk factors in type 1 diabetes.

Glycemic Control and CVD Risk

The associations between elevated hemoglobin A1c and excess CVD mortality are clear [3] and have been substantiated in the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) follow-up of the effects of intensive glucose control in the Diabetes Control and Interventions Trial (DCCT) [7,8] and a population based registry study from Sweden comparing patients with T1D with age matched controls [3]. However, the relationship between A1c elevations and CVD risk, especially coronary artery disease (CAD) risk, appears to be weaker than the relationship between elevated A1c and microvascular complications in individuals with T1D [9,10].

Poor glycemic control in persons with T1D increases risk for diabetic nephropathy and diabetic nephropathy, in turn, is associated with premature CAD; thus diabetic nephropathy may account for a significant portion of the excess CVD risk found in individuals with T1D [9,11]. Recent studies have tried to sort out an independent effect of glycemic control on CVD risk in T1D. In a longitudinal study[12], renal disease (defined as diabetic nephropathy, end stage renal disease or dialysis-related complications) contributed to 67% of all CVD deaths before 20 years’ duration of T1D and to 85% of all CVD deaths after 30 years T1D duration. Even patients with the earliest and mildest form of diabetic kidney disease, with increased albumin excretion (microalbuminuria) below the proteinuric range, experienced excess CVD mortality versus individuals with T1D and normal albumin excretion [13]. Poorer glycemic control is closely linked to elevated albumin excretion in youth with T1D. In youth participating in the T1D Exchange clinic registry study, those youth with an A1c ≥9.5% had about 5 times the odds of microalbuminuria versus youth with an A1c of 6.5-<7.5% [14].

It is likely that improving glycemic control in T1D will lead to significant reductions in CVD risk. American Diabetes Association glycemic targets have recently been lowered and are now harmonized with the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes target of a hemoglobin A1c <7.5% for children with diabetes <18 years old [15,16]. Unfortunately, national and international data consistently describe that youth with T1D are not meeting glycemic targets [17]. In the United States, minority youth especially struggle to reach glycemic targets [18,19]. Adolescents in the late teenage years and young adults during the years of emerging adulthood in the early 20s demonstrate higher A1cs than younger youth [19–21], suggesting that increased autonomy in self-management tasks and competing social and emotional issues during these vulnerable periods contribute to the hyperglycemia and uncontrolled diabetes.

Identifying approaches to improve self-care behaviors to optimize glycemic control during these critical developmental stages is particularly important as antecedents of clinical CVD and CAD are certainly evident by the end of the 2nd decade and the beginning of the 3rd decade of life. However, it is never too late to work towards optimal glycemic control; even after the onset of kidney disease, improvements in glycemic control can favorably alter the risk of diabetic kidney disease progression [22]. Many studies have examined family-based behavioral interventions aimed at improving adherence and glycemic control in youth with T1D [23,24]. In a meta-analysis of adherence-based interventions in pediatric T1D, studies that targeted psychosocial factors in addition to process-oriented, behavioral factors were most effective, although the pooled effect of these interventions on A1c was modest [25]. Technological advances in insulin delivery are also helping to improve glycemic control. Insulin pump therapy with continuous glucose monitoring yielded greater improvement in A1c than multiple daily injections in a 1-year randomized clinical trial [26]. Integrating the continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump into closed loop/artificial pancreas technologies increases glucose time in range in research studies [27,28] but is not yet available for clinical use. Short of therapies that restore or replace beta-cell function, further advances in automated insulin delivery that can simplify diabetes self-care are needed to allow the majority of youth to achieve optimal glycemic control aimed at reducing CVD risk.

Dyslipidemia

Rates of dyslipidemia in the general pediatric population and in pediatric patients with well-controlled T1D are similar. In 164 youth with T1D participating in the SEARCH for diabetes in youth cohort study with A1c <7.5%, rates of total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dl, LDL≥130 mg/dl, or HDL ≤35 mg/dl were each present in 7–8% of the SEARCH study population [29], rates that were slightly lower than those in a comparison population of youth without diabetes. In that same study, rates of elevated triglycerides (≥150 mg/dl) were better in the youth with well-controlled diabetes compared to the youth without diabetes. However, elevations in A1c have been shown to lead to elevations in LDL cholesterol [30,31] and, thus, youth with sub-optimally controlled diabetes have a more atherogenic lipid profile than youth without T1D [29]. Furthermore, rates of atherogenic LDL cholesterol subtypes such as elevated ApoB levels and elevated small, dense LDL particles are greater in youth with T1D than youth without diabetes regardless of metabolic control [29].

The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) [32], American Diabetes Association (ADA) [33] and American Heart Association (AHA) [34] each have guidelines for the evaluation and management of dyslipidemia in pediatric patients with diabetes. While the guidelines differ slightly (Table 1), all agree that dyslipidemia should be more aggressively managed in youth with diabetes versus youth without diabetes. The Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications study demonstrated that LDL ≥100 mg/dl and HDL <45 mg/dl at baseline significantly increased coronary artery disease risk 10 years later, providing epidemiological evidence for lipid targets in individuals with T1D [35]. All guidelines recommend lifestyle changes that include a diet limiting fat intake, exercise, and/or improved glycemic control as first steps in lipid management. While studies focused on lifestyle counselling to improve dyslipidemia in pediatric T1D have not been completed, lifestyle interventions in youth with hyperlipidemia, with obesity, or in the general school-based population have generally shown only modest improvements in lipid levels [36–38]. One interventional study was particularly successful in lowering LDL cholesterol in obese, predominantly Black and Hispanic pediatric patients ages 8–16 who did not generally have elevated LDL at baseline [39]. The intervention was a family-based group intervention consisting of group exercise sessions, behavioral modification sessions and nutrition education. At 24 months, in the intervention group, LDL levels had decreased 4 mg/dl from baseline and were 10 mg/dl less than in youth randomized to the control group (p=.01). In a national survey, the most frequently reported barrier to managing dyslipidemia in youth with type 2 diabetes, reported by over three quarters of pediatric endocrinologists, was difficulty enacting lifestyle changes [40]. These endocrinologists were acknowledging what pediatric studies also demonstrate; even in the best of circumstances, lifestyle changes sufficient to resolve dyslipidemia remain elusive in youth.

Table 1.

Chart of the guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia and hypertension.

| Organization | Screening | Initial Treatment | When to Start Medication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Guidelines | Statin Therapy | ||

|

American Diabetes Association(American Diabetes Association S5–S87) |

|

|

|

|

American Heart Association(Kavey et al. 1562–66) |

|

|

|

|

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute(Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents S213– S256) |

|

|

|

| BP Guidelines |

ACE Inhibitor/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker |

||

|

American Diabetes Association(American Diabetes Association S5–S87) |

|

|

|

|

American Heart Association(Kavey et al. 1562–66) |

|

|

|

|

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute(Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents S213– S256) |

|

|

|

Reference List

American Diabetes Association. "Standards of medical care in diabetes--2015." Diabetes Care 38 Suppl 1 (2015): S5–S87.

Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. "Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report." Pediatrics 128 Suppl 5 (2011): S213–S256.

Kavey, R. E., et al. "American Heart Association guidelines for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease beginning in childhood." Circulation 107.11 (2003): 1562–66.

Medication use for pediatric dyslipidemia also remains challenging. The primary lipid derangement for which medications are indicated is high LDL. Guidelines consistently recommend using statins as first-line therapy, however, studies document insufficient medication use for high LDL in youth with T1D. In the SEARCH cohort, 3% of pediatrics patients over 10 years of age had an LDL >160 mg/dl, while only 1% were treated with lipid-lowering medications [41]. In another cohort, only 3% of those who qualified for statin therapy based upon ADA guidelines were being treated with a lipid-lowering medication [42]. The substantial changes in guidelines for cholesterol management for adults with diabetes [43] are discordant with pediatric guidelines and may be leading to confusion for pediatric diabetes providers. In the 2013 guidelines recommended that all individuals age ≥40 years with T1D should be placed on a statin while very few individuals with T1D age <40 years with LDL <190 mg/dl would qualify for statin therapy. If pediatric endocrinologists were to follow both pediatric ADA guidelines and adult AHA guidelines, they would be placing teenage patients on statins for LDLs ≥130 mg/dl (in the presence of additional CVD risk factors) only to stop them again when the patient reached adulthood. In addition to the discordance between pediatric and adult guidelines, pediatric diabetes providers may also be concerned about the lack of evidence to direct their choice of the optimal age to initiate therapy, the LDL level (if any) indicating the need to initiate therapy, the target LDL level, and/or statin dose to use. The Adolescent Type 1 Diabetes Cardio-renal Intervention Trial (AdDIT) [44], a multinational randomized controlled study of ace inhibitors and statin therapy in high-risk adolescents with T1D (defined as those with high normal urinary albumin excretion) is projected to finish in 2016 [45] and should provide valuable data on the safety and efficacy of statin therapy in adolescents with T1D and on clinical outcomes related to diabetic renal disease, c-IMT, and CVD risk.

Overweight/Obesity

Data about the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children with T1D vary [46]. The global TEENS study showed that around 17% of children and adolescents with T1D are overweight and an additional 10% are obese [47]. In the United States, the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study demonstrated that 34% of youth with T1D are overweight or obese, which is similar to US youth without diabetes (33%) [48]. As has been demonstrated in US youth without diabetes, minority youth (African-American, Asian or Pacific Islander, American Indian, Hispanic) with T1D have a higher risk of obesity than Non-Hispanic white youth with T1D [48].

In addition to traditional risk factors associated with weight gain in the general population, such as high energy intake, poor dietary quality, sedentary behavior, decreased physical activity, and an obesogenic environment [49], specific features related to insulin treatment also contribute to weight gain in youth with T1D. Intensive insulin therapy may lead to weight gain, or can impede efforts at weight loss. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) demonstrated the benefits of tight glucose control on reducing the development of microvascular complications of T1D [50], but also yielded a threefold higher rate of weight gain for patients receiving intensive insulin therapy [51]. Thus, while intensive insulin therapy during the DCCT has been shown to lower the development of micro- and macrovascular complications in patients with T1D, its beneficial effects may be partially offset by concomitant weight gain due to the occurrence of obesity-associated CVD risk factors [52]. Fortunately, recently published data suggest that current approaches to intensive insulin therapy, using more physiologic insulin delivery with insulin analogs and pump therapy, is no longer associated with an increased occurrence of overweight and obesity in youth with T1D [53]. On the other hand, the rates of overweight and obesity in youth with T1D remain elevated at ~33%, as noted above [48]. Prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity with educational and behavioral strategies focused on improving diet and increasing physical activity remain the mainstay of management. Nevertheless, these strategies often yield limited success in the general population, and there are additional barriers to successful implementation in youth with T1D. Young children with T1D consume high-fat, low-fiber diets when compared to youth in the general population in American, European, and Asian cohorts of children [54–56,56]. It has been hypothesized that the attention to matching insulin to carbohydrate intake, may impact on the consumption of other macronutrients [57]. Recommended intakes are rarely achieved in T1D youth, and modifying dietary behaviors represents one of the most challenging goals of nutrition education. Due to environmental, physiological, cultural, and social factors, dietary behavior changes are difficult and often met with ambivalence or resistance [58]. As unhealthy dietary habits may affect the risk of long-term complications, new approaches to support families to facilitate healthful eating are needed. Nutrition education is recognized as necessary, but insufficient as the sole strategy to address all of the factors that impact dietary behaviors. Behavioral approaches that increase motivation and promote skill development for children and families may increase the likelihood of achieving dietary behavior change [59]. Further studies on behavioral nutrition interventions in T1D youth are needed.

Technologies may support the education process. The use of smartphone tools, such as text messaging or applications to monitor dietary intake, could successfully support healthy lifestyle activity, provide education, and encourage healthy nutrition. In a recent study, the feasibility and acceptability of a daily text messaging intervention focused on nutrition and healthy lifestyle activities in youth with T1D was examined [60]. The majority of participants (82%) found the text messaging support useful in helping them with their health goals, opening new lines of investigation to support behavior modification. The cost of these kinds of interventions still remains a barrier to consistent use in large populations.

Regular physical activity is known to have a positive impact on muscle mass, strength, bone density, cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, psychological health, and executive functioning [61]. In young persons with T1D, a beneficial effect of exercise has been reported on total cholesterol, triglyceride levels, A1c, and insulin sensitivity [62]. Nonetheless, a vast majority of youth with T1D spend less time physically active compared to their peers without diabetes [61]. Exercise can be especially challenging for youth with T1D due to the occurrence of exercise induced hypoglycemia [63]. The improved flexibility of new insulin regimens, new insulin analogs, and the greater use of insulin pump therapy have reduced the occurrence of hypoglycemic events but hypoglycemia remains a challenge and often an impediment to exercise for youth with T1D [61,64]. Hypoglycemia in response to exercise demands urgent treatment with additional carbohydrates, sometimes negating the weight benefits of exercise for overweight/obese youth. General guidelines exist for prevention of hypoglycemia during and after exercise [63]; however the majority of studies upon which the management recommendations are based have excluded obese youth with T1D (BMI’s ≥95th percentile) [53,63].

The complex decision making to ensure the right amount and timing of insulin administration, food ingestion before and after exercise, and an understanding of post-exercise glycemic excursions can also discourage youth with T1D from regular physical activity [61]. Individualized plans to manage hypoglycemia during and after exercise may help youth with T1D exercise successfully. New algorithms and decision support technologies may assist in exercise management; these include suspension of basal rates or temporary basal rates for those using pump therapy and the use of real-time continuous glucose monitoring systems [65,66]. Similarly, the low glucose suspend pump feature available with sensor augmented pumps has been shown to reduce the duration and severity of exercise-induced hypoglycemia in adults, without causing rebound hyperglycemia [67]. It is important to support families and youth with T1D in overcoming barriers to practice physical activity by personalizing the management plan.

Obesity and its associated insulin resistance may also improve in obese persons with T1D by pharmacological treatments. Metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist therapy, or sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor therapy may be beneficial therapies for glucose control and the management of co-morbid obesity in adults with T1D [68]. In a recent randomized controlled trial of overweight and obese adolescents with T1D, metformin reduced insulin requirements, suggesting a beneficial role for metformin therapy in overweight and obese youth with T1D[69]. Future research should also address identifying approaches for successful weight management in the substantial numbers of pediatric patient with T1D who are overweight and obese given the challenges associated with exogenous insulin therapy.

Hypertension

Around 4–6% of youth with T1D have elevated blood pressures in the hypertensive range on 1–2 occasions [42,70,71], a rate similar to that found in youth without T1D. Minority youth with T1D, especially Asian Pacific Islanders and American Indians, have substantially higher rates of blood pressure elevations [70]. As has been demonstrated in other populations, overweight and obesity increase the risk of elevated blood pressure in youth with T1D [70]. Studies also demonstrate a relationship between elevated A1c and elevated blood pressure but a causal relationship between high A1c levels and high blood pressure has not yet been established [70].

Recommendations for the treatment of hypertension and prehypertension in youth with T1D differ slightly between ADA guidelines [33] and NHLBI guidelines [32]. NHLBI guidelines distinguish between prehypertension (BP mean that is ≥90th percentile for age, sex, and height or ≥120/80), Stage 1 Hypertension (defined as mean BP ≥95th percentile for age, sex, and height but <99th percentile plus 5 mmHg), and Stage 2 Hypertension (defined as mean BP ≥ 99th percentile plus 5 mmHg) in order to determine the speed and intensity of the workup as well as treatment strategies. The NHLBI guidelines use identical criteria for the evaluation and treatment of elevated BP in youth with and without diabetes, however the treatment target for youth with T1D is a BP <90th percentile for age, sex, and height while for the general population, it is <95th percentile for age, sex, and height. ADA guidelines differ from the NHLBI guidelines by recommending that clinicians consider medications even for blood pressures ≥90th percentile for age, sex, and height (prehypertensive range) if, after 3–6 months of therapeutic lifestyle efforts, BP shows no improvement. Epidemiological evidence for more intensive management of blood pressure in individuals with T1D comes from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications trial, which shows greater than twice the risk for coronary artery disease when the baseline blood pressure was ≥120/90 ten years earlier [35].

The effective management of hypertension in youth remains challenging. Hypertension is not appropriately diagnosed in the majority of both youth in the general pediatric population [72] and youth with T1D [71] with persistent elevations in blood pressure measurements over time. Interventions targeting lifestyle change, including healthy eating and exercise in youth in the general population [38] or in overweight and obese youth [37,39,73] achieve, at most, only small (<2 mmHg) reductions in blood pressure, demonstrating the challenges of implementing effective lifestyle changes for blood pressure management in the pediatric population. Medications, typically angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, are recommended in youth with diabetes and hypertension when lifestyle changes are unsuccessful. However, a recent large U.S. study demonstrated that only 52% of youth with T1D and hypertension (documented by providers in the medical record) were prescribed such therapies and only 32% of those who were treated achieved BP treatment goals [71]. In addition to providing information on statin therapy, the AdDIT trial will provide much needed data on the safety and efficacy of ace inhibitor therapy in youth with T1D [44].

Pediatric Antecedents of CVD: Surrogate Markers of CVD and Associations with Traditional Risk Factors

While the mechanisms behind vascular pathology in youth with obesity and type 2 diabetes have been described [74], the mechanisms underlying vascular pathology as well as the timeliness and need for interventions in youth with T1D are less well understood [75–78]. Endothelial dysfunction and early atherosclerosis relate to hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and hypertension [79,80] as subsequently described.

Surrogate Markers of CVD: Endothelial dysfunction

Because CVD rarely presents in childhood or adolescence, clinical investigators are seeking early markers of increased CVD risk in youth with T1D. Alterations in vascular function typically precede the development of vascular anatomical pathology [76,78] and include reduced endothelial function, reduced arterial compliance, and an increase in circulating inflammatory markers [74]. Endothelial dysfunction is the inability of the artery to sufficiently dilate in response to an appropriate endothelial stimulus [77] and it is an early event in the development of atherosclerosis [77,81]. Several mechanisms and markers of the mechanisms have been implicated in endothelial dysfunction, for example, hyperglycemia [79], oxidative stress, advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), protein kinase C and polyol-pathway activation [82], and inflammation noted by elevations in C reactive protein [79,83]. The dysfunctional endothelium adopts a prothrombotic, proinflammatory, and vasoconstrictive phenotype promoting the early development of atherosclerosis [81,84].

Endothelial function can be assessed non-invasively by flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery; this assessment of endothelial fitness has increased the feasibility of identifying CVD risk in pediatric patients [82]. In youth with T1D, peak FMD was found to be significantly lower in children and adolescents with T1D compared to healthy controls [5,79]. Moreover, the presence of endothelial dysfunction is positively correlated with early structural atherosclerotic damage, measured by carotid intima-media thickness (c-IMT) [5]. Recent data has shown c-IMT mean values to be higher in T1D adolescents compared with healthy controls (p<0.02) [85]. Additionally, in youth with T1D, the rate of urinary albumin excretion positively correlated with aortic intimal media thickness (a-IMT), which is a measure of sublinical atherosclerosis, suggesting that the relationship between renal disease and atherosclerosis may begin in childhood [86].

Surrogate Markers of CVD: Arterial Stiffness

Functional and structural changes in the artery wall can reduce arterial compliance, limiting distension of the arterial vessel during systole; favoring obstructive and thrombotic events of the atherosclerotic process [87]. Structural changes in the artery wall differ in the large and small arteries, and include modifications of elastin, collagen fibers and smooth muscle cells. Alterations in function and structure of arterial wall are the earliest changes in the atherosclerotic process in individuals without and with diabetes [88,89]. Recent results from the SEARCH Study demonstrated that increased arterial stiffness (measured by carotid-femoral vascular segment pulse wave velocity, augmentation index and brachial artery distensibility) is present in youth with T1D compared to matched controls without T1D, after controlling for traditional risk factors. These findings indicate that T1D can affect both central and peripheral vasculature [90] and support previous reports [91,92].

Surrogate Markers of CVD and Glycemic control

Hyperglycemia can cause endothelial injury and dysfunction, increasing oxidative stress, via an increase in reactive oxygen species and a reduction of antioxidant reserves [79]. A positive correlation between c-IMT and fasting blood glucose levels (r=0.47, p<0.05) has been demonstrated in adolescents with T1D [79]. Further, there is a positive correlation between long-term hyperglycemia and endothelial dysfunction [93,94], with a key role played by the historical mean A1c rather than current A1c, supporting the role of metabolic memory in determining future vascular damage [93,94]. Thus, further investigations are needed to detect if early markers of vascular damage may be reversed in response, for example, to intensive insulin therapy leading to improved glycemic control [80]. In a clinical trial, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress are partially reversed by intensive insulin therapy [95].

Surrogate Markers of CVD and Dyslipidemia

Hypercholesterolemia has also been associated with an increase in c-IMT in children and youth without diabetes [96]. T1D in youth may impact lipid levels (see above) as well as c-IMT [97,98]. Children with T1D who demonstrate endothelial dysfunction compared to those without endothelial dysfunction have higher concentrations of LDL-cholesterol [5]. Higher triglyceride to HDL-C ratio has also been associated with increased arterial stiffness in youth with T1D [90].

Surrogate Markers of CVD and Overweight/Obesity

Body composition and z-BMI may also affect endothelial function and atherosclerosis. The pro-inflammatory action of obesity and its association with insulin resistance promote the development and progression of atherosclerosis [99]. Obese children and adolescents have altered endothelial function and increased c-IMT when compared to healthy controls [100–103]. In a recent study, c-IMT scores were compared among youth with T1D, obese youth, and controls, and demonstrated higher c-IMT in both youth with T1D and obese youth, with the highest c-IMT scores in obese youth [85]. The potential additive effects of both obesity and T1D on c-IMT warrant further studies.

Surrogate Markers of CVD and Hypertension

Blood pressure is strongly associated with endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and c-IMT [74]. Systolic blood pressure is inversely associated with endothelial function [104] and directly related to arterial stiffness [88,90] and c-IMT [105]. Additional information regarding c-IMT and anti-hypertensive treatment in youth with T1D should be forthcoming in the AdDIT study.

Conclusions

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of premature mortality in patients with T1D. Addressing cardiovascular risk factors during the pediatric and young adult years is likely critical in order to reduce risk for CVD and avoid reductions in life expectancy for persons with T1D. Traditional CVD risk factors, including dyslipidemia, overweight/obesity, hypertension, and smoking, as contributors to CVD risk in patients with T1D, should all be assessed and managed aggressively. Additionally, hyperglycemia and poorly controlled diabetes remain potent predictors of overall mortality and CVD.

Achieving optimal glycemic control continues to be problematic for the overwhelming majority of young persons with T1D. In addition, persons from racial and ethnic minority groups often experience greater challenges with achieving glycemic targets, possibly related to differences in socioeconomic status in these vulnerable subgroups. Recent data have uncovered disparities with respect to the use of advanced diabetes technologies in certain racial and ethnic minority groups [106,107]. Also, racial and ethnic minority groups experience a greater likelihood of developing components of the metabolic syndrome further increasing their risk for CVD. Thus, it is important to address traditional CVD risk factors as well as glycemic control in all pediatric and young adult patients with T1D, with particular attention given to those from racial and ethnic minority groups. Providers should be attuned to the pediatric guidelines for identification and management of dyslipidemia, overweight/obesity, and hypertension with interventions delivered in a culturally sensitive manner especially across the pediatric age span and different racial and ethnic groups.

In the current era, there are many opportunities to preserve health and prevent complications for young persons with T1D. However it remains evident that persons with T1D continue to experience reduced life expectancy, with CVD as the major contributor to premature mortality. Attention to cardiovascular risk factors during the pediatric years along with efforts aimed at optimizing glycemic control may reverse this trend.

Acknowledgments

Lori Laffel reports personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, NovoNordisk, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb/AstraZeneca, Menarini, and Oshad; grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Dexcom; and grants from Bayer.

Footnotes

Author contributions

LL, MK, and EG developed the theme idea and performed the work, drafted the manuscript, discussed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Michelle Katz and Elisa Giani declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Michelle Katz, Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult Section, Genetics and Epidemiology Section, Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, One Joslin Place, Boston, MA 02215, Phone: 617-309-4633, Michelle.Katz@joslin.harvard.edu.

Elisa Giani, Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult Section, Genetics and Epidemiology Section, Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, One Joslin Place, Boston, MA 02215, Phone: 617-309-4460, Elisa.Giani@joslin.harvard.edu.

Lori Laffel, Chief, Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult Section, Senior Investigator, Genetics and Epidemiology Section, Joslin Diabetes Center, Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, One Joslin Place, Boston, MA 02215, Phone 617.732.2603, FAX 617.309.2451, lori.laffel@joslin.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Research Group. Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Design, implementation, and preliminary results of a long-term follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial cohort. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(1):99–111. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soedamah-Muthu SS, Chaturvedi N, Witte DR, et al. Relationship between risk factors and mortality in type 1 diabetic patients in Europe: the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study (PCS) Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1360–1366. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lind M, Svensson AM, Kosiborod M, et al. Glycemic control and excess mortality in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(21):1972–1982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408214. This study provides data on the excess risk of death according to the level of glycemic control from the Swedish National Diabetes Register.

- 4.Berenson GS. Childhood risk factors predict adult risk associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease. The Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(10C):3L–7L. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02953-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eltayeb AA, Ahmad FA, Sayed DM, Osama AM. Subclinical vascular endothelial dysfunctions and myocardial changes with type 1 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35(6):965–974. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-0883-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harjutsalo V, Maric-Bilkan C, Forsblom C, Groop PH. Impact of sex and age at onset of diabetes on mortality from ischemic heart disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):144–148. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0377. This study demonstrates the gender (female) as risk factor for ischenic heart disease.

- 7. Orchard TJ, Nathan DM, Zinman B, et al. Association between 7 years of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes and long-term mortality. JAMA. 2015;313(1):45–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16107. This study investigates the impact of insulin intensive therapy on mortality in the long-term follow-up of the DCCT cohort.

- 8.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(25):2643–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orchard TJ, Costacou T, Kretowski A, Nesto RW. Type 1 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2528–2538. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fullerton B, Jeitler K, Seitz M, et al. Intensive glucose control versus conventional glucose control for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD009122. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009122.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torffvit O, Lovestam-Adrian M, Agardh E, Agardh CD. Nephropathy, but not retinopathy, is associated with the development of heart disease in Type 1 diabetes: a 12-year observation study of 462 patients. Diabet Med. 2005;22(6):723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Secrest AM, Becker DJ, Kelsey SF, LaPorte RE, Orchard TJ. Cause-specific mortality trends in a large population-based cohort with long-standing childhood-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2010;59(12):3216–3222. doi: 10.2337/db10-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groop PH, Thomas MC, Moran JL, et al. The presence and severity of chronic kidney disease predicts all-cause mortality in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1651–1658. doi: 10.2337/db08-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels M, Dubose SN, Maahs DM, et al. Factors associated with microalbuminuria in 7,549 children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes in the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2639–2645. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiang JL, Kirkman MS, Laffel LM, Peters AL. Type 1 diabetes through the life span: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(7):2034–2054. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) ISPAD Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Children and Adolescents. 2000 Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood JR, Miller KM, Maahs DM, et al. Most youth with type 1 diabetes in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry do not meet American Diabetes Association or International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes clinical guidelines. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2035–2037. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petitti DB, Klingensmith GJ, Bell RA, et al. Glycemic control in youth with diabetes: the SEARCH for diabetes in Youth Study. J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerstl EM, Rabl W, Rosenbauer J, et al. Metabolic control as reflected by HbA1c in children, adolescents and young adults with type-1 diabetes mellitus: combined longitudinal analysis including 27,035 patients from 207 centers in Germany and Austria during the last decade. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167(4):447–453. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clements MA, Foster NC, Maahs DM, et al. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) changes over time among adolescent and young adult participants in the T1D exchange clinic registry. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015 doi: 10.1111/pedi.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller KM, Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, et al. Evidence of a strong association between frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c levels in T1D exchange clinic registry participants. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2009–2014. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skupien J, Warram JH, Smiles A, et al. Improved glycemic control and risk of ESRD in patients with type 1 diabetes and proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(12):2916–2925. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013091002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laffel LM, Vangsness L, Connell A, et al. Impact of ambulatory, family-focused teamwork intervention on glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2003;142(4):409–416. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz ML, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM. Family-based psychoeducation and Care Ambassador intervention to improve glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes: a randomized trial. Pediatr Diabetes. 2014;15(2):142–150. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hood KK, Rohan JM, Peterson CM, Drotar D. Interventions with adherence-promoting components in pediatric type 1 diabetes: meta-analysis of their impact on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1658–1664. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergenstal RM, Tamborlane WV, Ahmann A, et al. Effectiveness of sensor-augmented insulin-pump therapy in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):311–320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dauber A, Corcia L, Safer J, et al. Closed-loop insulin therapy improves glycemic control in children aged <7 years: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):222–227. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hovorka R, Elleri D, Thabit H, et al. Overnight closed-loop insulin delivery in young people with type 1 diabetes: a free-living, randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(5):1204–1211. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guy J, Ogden L, Wadwa RP, et al. Lipid and lipoprotein profiles in youth with and without type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(3):416–420. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maahs DM, Dabelea D, D’Agostino RB, Jr, et al. Glucose control predicts 2-year change in lipid profile in youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2013;162(1):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.006. This epidemiological study describes how changes in glucose control impact changes in the lipid profile in a large cohort of youth with T1D participating in the SEARCH study.

- 31.Reh CM, Mittelman SD, Wee CP, et al. A longitudinal assessment of lipids in youth with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12(4 Pt 2):365–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128(Suppl 5):S213–S256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl 1):S5–S87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavey RE, Daniels SR, Lauer RM, et al. American Heart Association guidelines for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease beginning in childhood. Circulation. 2003;107(11):1562–1566. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061521.15730.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orchard TJ, Forrest KY, Kuller LH, Becker DJ. Lipid and blood pressure treatment goals for type 1 diabetes: 10-year incidence data from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1053–1059. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obarzanek E, Kimm SY, Barton BA, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of a cholesterol-lowering diet in children with elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: seven-year results of the Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC) Pediatrics. 2001;107(2):256–264. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelishadi R, Hashemipour M, Mohammadifard N, Alikhassy H, Adeli K. Short- and long-term relationships of serum ghrelin with changes in body composition and the metabolic syndrome in prepubescent obese children following two different weight loss programmes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69(5):721–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eagle TF, Gurm R, Smith CA, et al. A middle school intervention to improve health behaviors and reduce cardiac risk factors. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savoye M, Nowicka P, Shaw M, et al. Long-term results of an obesity program in an ethnically diverse pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):402–410. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong K, Potter A, Mulvaney S, et al. Pediatric endocrinologists’ management of children with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):512–514. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kershnar AK, Daniels SR, Imperatore G, et al. Lipid abnormalities are prevalent in youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. J Pediatr. 2006;149(3):314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Margeirsdottir HD, Larsen JR, Brunborg C, Overby NC, Dahl-Jorgensen K. High prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(4):554–561. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0921-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S1–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adolescent type 1 Diabetes Cardio-renal Intervention Trial (AdDIT) BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.AdDit Adolescent Type 1 Diabetes Intervention Trial. 2015 7-9-2015. Ref Type: Online Source. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frohlich-Reiterer EE, Rosenbauer J, Bechtold-Dalla PS, et al. Predictors of increasing BMI during the course of diabetes in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: data from the German/Austrian DPV multicentre survey. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(8):738–743. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304237. This study address risk factors for the increase in BMI during the course of diabetes.

- 47.Lifestyle factors associated with glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes (T1D): the Global TEENs Study. ISPAD. 2014 Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu LL, Lawrence JM, Davis C, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in youth with diabetes in USA: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11(1):4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lake A, Townshend T. Obesogenic environments: exploring the built and food environments. J R Soc Promot Health. 2006;126(6):262–267. doi: 10.1177/1466424006070487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Libman IM, Pietropaolo M, Arslanian SA, LaPorte RE, Becker DJ. Changing prevalence of overweight children and adolescents at onset of insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(10):2871–2875. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Diabetes Association. Implications of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes. 1993;42(11):1555–1558. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Purnell JQ, Zinman B, Brunzell JD. The effect of excess weight gain with intensive diabetes mellitus treatment on cardiovascular disease risk factors and atherosclerosis in type 1 diabetes mellitus: results from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study (DCCT/EDIC) study. Circulation. 2013;127(2):180–187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.077487. This study demonstrates the associations of excess weight gain with sustained increases in central obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and blood pressure, as well as more extensive atherosclerosis during the EDIC follow-up study.

- 53. Baskaran C, Volkening LK, Diaz M, Laffel LM. A decade of temporal trends in overweight/obesity in youth with type 1 diabetes after the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(4):263–270. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12166. This study demonstrates stable trends of overweight/obesity in youth with T1D over a 10 years period.

- 54.Mayer-Davis EJ, Nichols M, Liese AD, et al. Dietary intake among youth with diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(5):689–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mehta SN, Volkening LK, Quinn N, Laffel LM. Intensively managed young children with type 1 diabetes consume high-fat, low-fiber diets similar to age-matched controls. Nutr Res. 2014;34(5):428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.04.008. This study compared dietary intake in youth with T1D vs general US youth, demonstrating that young children with T1D consume high-fat, low-fiber diets compared to the general population.

- 56.Patton SR, Dolan LM, Powers SW. Dietary adherence and associated glycemic control in families of young children with type 1 diabetes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mehta SN, Haynie DL, Higgins LA, et al. Emphasis on carbohydrates may negatively influence dietary patterns in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(12):2174–2176. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minges KE, Magliano DJ, Owen N, et al. Associations of strength training with impaired glucose metabolism: the AusDiab Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(2):299–303. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31826e6cd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nansel TR, Laffel LM, Haynie DL, et al. Improving dietary quality in youth with type 1 diabetes: randomized clinical trial of a family-based behavioral intervention. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:58. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0214-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Markowitz JT, Schultz AT, Cousineau TM, Franko DL, Laffel LMB. Mobile Health (mHealth) Intervention Using Text Messaging Aimed at Healthy Lifestyles for Youth with Diabetes (DM): A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) In preparation. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pivovarov JA, Taplin CE, Riddell MC. Current perspectives on physical activity and exercise for youth with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(4):242–255. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12272. This review highlights benefits and barriers od physical activity in youth with T1D and present a new algorithm for the management of insulin therapy during sport activity.

- 62.Quirk H, Blake H, Tennyson R, Randell TL, Glazebrook C. Physical activity interventions in children and young people with Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2014;31(10):1163–1173. doi: 10.1111/dme.12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):e147–e167. doi: 10.2337/dc10-9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tamborlane WV. Triple jeopardy: nocturnal hypoglycemia after exercise in the young with diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):815–816. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taplin CE, Cobry E, Messer L, et al. Preventing post-exercise nocturnal hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2010;157(5):784–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riddell MC, Milliken J. Preventing exercise-induced hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes using real-time continuous glucose monitoring and a new carbohydrate intake algorithm: an observational field study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(8):819–825. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garg S, Brazg RL, Bailey TS, et al. Reduction in duration of hypoglycemia by automatic suspension of insulin delivery: the in-clinic ASPIRE study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(3):205–209. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Polsky S, Ellis SL. Obesity, insulin resistance, and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2015;22(4):277–282. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Libman I, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al. Metformin as an adjunct therapy does not improve glycemic control among overweight adolescents with type 1 diabetes (T1D) [Abstract] Endocr Rev. 2015;36(2 (Suppl)):OR01–OR05. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr. 2010;157(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nambam B, Dubose SN, Nathan BM, et al. Therapeutic inertia: underdiagnosed and undertreated hypertension in children participating in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry. Pediatr Diabetes. 2014 doi: 10.1111/pedi.12231. This study demonstrates the under-recognition and under-treatment of elevated blood pressure in youth with T1D being managed by pediatric diabetes centers.

- 72.Hansen ML, Gunn PW, Kaelber DC. Underdiagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2007;298(8):874–879. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.8.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pedrosa C, Oliveira BM, Albuquerque I, et al. Markers of metabolic syndrome in obese children before and after 1-year lifestyle intervention program. Eur J Nutr. 2011;50(6):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s00394-010-0148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Short KR, Blackett PR, Gardner AW, Copeland KC. Vascular health in children and adolescents: effects of obesity and diabetes. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:973–990. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s7116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarvisalo MJ, Putto-Laurila A, Jartti L, et al. Carotid artery intima-media thickness in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51(2):493–498. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Juonala M, Viikari JS, Kahonen M, et al. Childhood levels of serum apolipoproteins B and A-I predict carotid intima-media thickness and brachial endothelial function in adulthood: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(4):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF, Jr, Vita JA. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(7):1149–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Halcox JP, Donald AE, Ellins E, et al. Endothelial function predicts progression of carotid intima-media thickness. Circulation. 2009;119(7):1005–1012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.765701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jarvisalo MJ, Raitakari M, Toikka JO, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and increased arterial intima-media thickness in children with type 1 diabetes. Circulation. 2004;109(14):1750–1755. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124725.46165.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bertoluci MC, Ce GV, da Silva AM, et al. Endothelial dysfunction as a predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(5):679–692. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i5.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD. Vascular complications in diabetes mellitus: the role of endothelial dysfunction. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;109(2):143–159. doi: 10.1042/CS20050025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haller MJ, Stein J, Shuster J, et al. Peripheral artery tonometry demonstrates altered endothelial function in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8(4):193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.King GL, Loeken MR. Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress in diabetic complications. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122(4):333–338. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bakker W, Eringa EC, Sipkema P, van Hinsbergh VW. Endothelial dysfunction and diabetes: roles of hyperglycemia, impaired insulin signaling and obesity. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335(1):165–189. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Faienza MF, Acquafredda A, Tesse R, et al. Risk factors for subclinical atherosclerosis in diabetic and obese children. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(3):338–343. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Maftei O, Pena AS, Sullivan T, et al. Early Atherosclerosis Relates to Urinary Albumin Excretion and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: Adolescent Type 1 Diabetes cardio-renal Intervention Trial (AdDIT) Diabetes Care. 2014;37(11):3069–3075. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0700. This study demonstrates the correlation between high urinary albumin excretion and early atheroslerosis detected by aortic intima media thickness in youth with T1D.

- 87.Cohn JN, Quyyumi AA, Hollenberg NK, Jamerson KA. Surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease: functional markers. Circulation. 2004;109(25 Suppl 1):IV31–IV46. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133442.99186.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van BL, et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(21):2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(13):1318–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shah AS, Wadwa RP, Dabelea D, et al. Arterial stiffness in adolescents and young adults with and without type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH CVD study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(5):367–374. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haller MJ, Samyn M, Nichols WW, et al. Radial artery tonometry demonstrates arterial stiffness in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2911–2917. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Palombo C, Kozakova M, Morizzo C, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and large artery structure and function in young subjects with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:88. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ce GV, Rohde LE, da Silva AM, et al. Endothelial dysfunction is related to poor glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes under 5 years of disease: evidence of metabolic memory. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(5):1493–1499. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ceriello A, Esposito K, Ihnat M, Thorpe J, Giugliano D. Long-term glycemic control influences the long-lasting effect of hyperglycemia on endothelial function in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(8):2751–2756. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Franklin VL, Khan F, Kennedy G, Belch JJ, Greene SA. Intensive insulin therapy improves endothelial function and microvascular reactivity in young people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51(2):353–360. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tonstad S, Joakimsen O, Stensland-Bugge E, et al. Risk factors related to carotid intima-media thickness and plaque in children with familial hypercholesterolemia and control subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(8):984–991. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Margeirsdottir HD, Stensaeth KH, Larsen JR, Brunborg C, Dahl-Jorgensen K. Early signs of atherosclerosis in diabetic children on intensive insulin treatment: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(9):2043–2048. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lamotte C, Iliescu C, Libersa C, Gottrand F. Increased intima-media thickness of the carotid artery in childhood: a systematic review of observational studies. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(6):719–729. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1328-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aggoun Y. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. Pediatr Res. 2007;61(6):653–659. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31805d8a8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Caballero AE, Bousquet-Santos K, Robles-Osorio L, et al. Overweight Latino children and adolescents have marked endothelial dysfunction and subclinical vascular inflammation in association with excess body fat and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):576–582. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aggoun Y, Szezepanski I, Bonnet D. Noninvasive assessment of arterial stiffness and risk of atherosclerotic events in children. Pediatr Res. 2005;58(2):173–178. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000170900.35571.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kapiotis S, Holzer G, Schaller G, et al. A proinflammatory state is detectable in obese children and is accompanied by functional and morphological vascular changes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(11):2541–2546. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000245795.08139.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tounian P, Aggoun Y, Dubern B, et al. Presence of increased stiffness of the common carotid artery and endothelial dysfunction in severely obese children: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358(9291):1400–1404. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06525-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pena AS, Wiltshire E, MacKenzie K, et al. Vascular endothelial and smooth muscle function relates to body mass index and glucose in obese and nonobese children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4467–4471. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reinehr T, Kiess W, de SG, Stoffel-Wagner B, Wunsch R. Intima media thickness in childhood obesity: relations to inflammatory marker, glucose metabolism, and blood pressure. Metabolism. 2006;55(1):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hilliard ME, Wu YP, Rausch J, Dolan LM, Hood KK. Predictors of deteriorations in diabetes management and control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Willi SM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in management and outcomes among children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):424–434. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]