Abstract

MOF (MYST1, KAT8) is the major H4K16 lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) in Drosophila and mammals and is essential for embryonic development. However, little is known regarding the role of MOF in specific cell lineages. Here we analyze the differential role of MOF in proliferating and terminally differentiated tissues at steady state and under stress conditions. In proliferating cells, MOF directly binds and maintains the expression of genes required for cell cycle progression. In contrast, MOF is dispensable for terminally differentiated, postmitotic glomerular podocytes under physiological conditions. However, in response to injury, MOF is absolutely critical for podocyte maintenance in vivo. Consistently, we detect defective nuclear, endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi structures, as well as presence of multivesicular bodies in vivo in podocytes lacking Mof following injury. Undertaking genome-wide expression analysis of podocytes, we uncover several MOF-regulated pathways required for stress response. We find that MOF, along with the members of the non-specific lethal but not the male-specific lethal complex, directly binds to genes encoding the lysosome, endocytosis and vacuole pathways, which are known regulators of podocyte maintenance. Thus, our work identifies MOF as a key regulator of cellular stress response in glomerular podocytes.

Introduction

Acetylation of core histones was first reported over 50 years ago.1 The acetyl modification is catalyzed by lysine acetyltransferases (KATs) and is essential for chromatin structure and assembly, as well as gene transcription. Although most KATs are critical for early embryogenesis, their functions later in development and adulthood vary in a context-dependent manner.2 For instance, the KAT3A (CBP) and KAT3B (p300) are required for embryonic development,3, 4 whereas they appear to have very limited functions in B- and T-cell development.5, 6 In contrast, KAT6A and KAT6B are highly specific during development and do not operate in a cell autonomous manner.7, 8, 9, 10 Thus, KATs need to be analyzed in a tissue-specific manner.

Based on the nature of their catalytic domain, KATs are divided into five families, among which the MYST (named based on founding members—MOZ, Ybf2/Sas3, Sas2 and Tip60 KATs) family is the largest and most diverse.11 One of the best-characterized KATs in the MYST-family is MOF (also known as MYST1 or KAT8) that specifically acetylates H4K16 in Drosophila,12 mouse13 and human.14, 15 MOF regulates various essential cellular functions such as cell cycle progression,14, 16 maintaining pluripotency in embryonic stem cells17 and responding to DNA damage.16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Highlighting its importance, mice lacking Mof do not develop past the blastocyst stage.13, 23 Until recently, the early lethality of Mof knockout animals also hindered the comprehensive analysis of MOF at later developmental stages and in differentiated cells. At this point, MOF has been shown to be required for optimal T-cell development24 and for the survival of cerebellar Purkinjie cells,25 however, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

In this study, we investigated the role of MOF in both proliferating and postmitotic cells under physiological and stress conditions. We find a critical requirement for MOF to activate transcription of genes required for cell cycle progression and for responding to stressful stimuli in terminally differentiated podocytes.

Results

MOF is critical for transcriptional activation of genes required for cell cycle progression

To better understand the importance of MOF in stress response, we initially established a model of proliferating cells where Mof could be easily removed. We cultured primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from E13.5 embryos carrying a floxed Mof allele13 (designated Moffl) with a CAG-Cre-ERT2 transgene (designated Cre-ERT2T/+), as well as respective controls. To induce deletion of Mof, MEFs were treated with tamoxifen (4-hydroxy tamoxifen) over 3.5 days. Under these conditions, the Mof locus recombined efficiently and no Mof mRNA or MOF protein were detected in Moffl/fl;Cre-ERT2T/+ cells (Figure 1a, Supplementary Figures 1a, b). Consistent with the known enzymatic function of MOF,13, 14 H4K16ac levels were highly diminished after the deletion of Mof (Figure 1a).

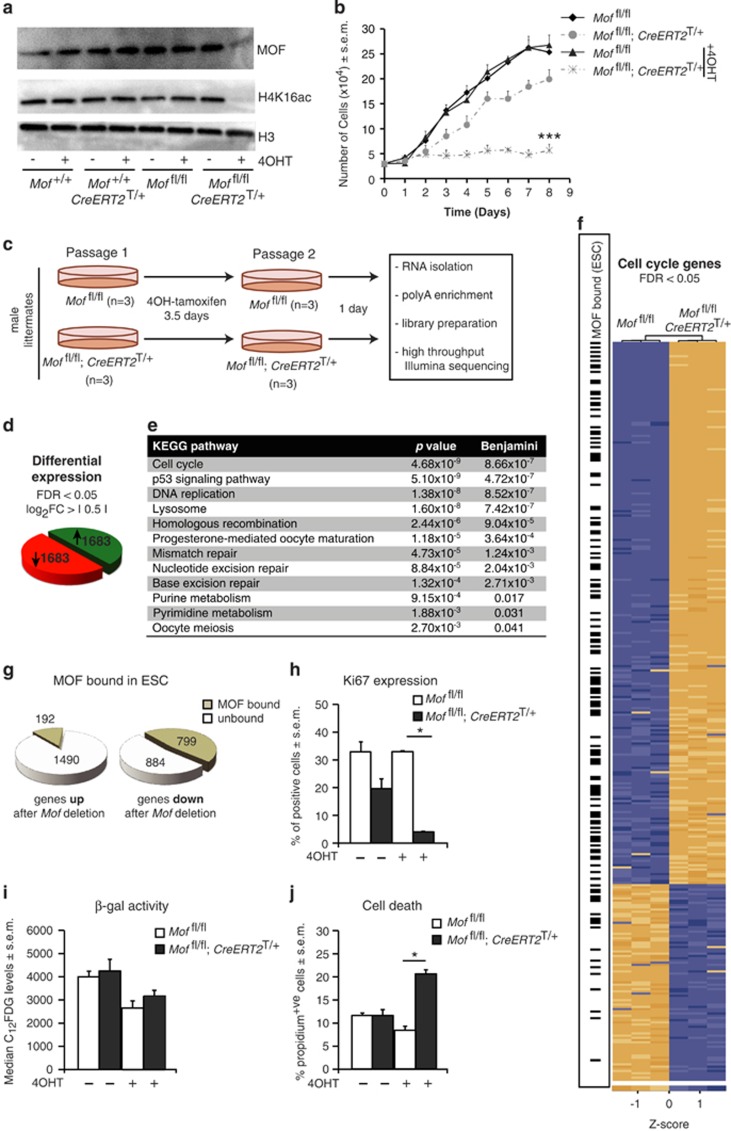

Figure 1.

MOF is required for cell cycle progression. (a) 4-Hydroxy tamoxifen (4OHT)-induced deletion of Mof in Moffl/fl;Cre-ERT2T/+ MEFs over 3.5 days leads to an absence of MOF protein and H4K16ac. (b) Growth curves of Mof-deleted and control MEFs. Mof-deleted MEFs fail to accumulate over the 8-day culture period compared with controls. (c) Experimental outline for culture of Mof MEFs and preparation for RNA sequencing. Passage 1 Moffl/fl;Cre-ERT2T/+ and Moffl/fl MEFs were treated with 4OHT over 3.5 days, passaged and taken 24 h later for expression analysis. (d) Number of differentially expressed genes in Mof-deleted versus control MEFs. A false discovery rate (FDR) cut-off of 0.05 and a log2-fold change cut-off of 0.5 was applied. (e) KEGG pathway analyses of genes differentially expressed in Mof-deleted MEFs. A Benjamani cut-off of 0.10 was applied. (f) Heat map representing cell cycle-related genes that are significantly changed in Mof-deleted MEFs compared with controls (FDR <0.05). The heat map displays normalized counts per gene in each of the three replicates. The majority of cell cycle genes were reduced in expression after Mof deletion and were positive for MOF binding (left panel). (g) Proportion of differentially expressed genes in Mof-deleted samples that are bound by MOF. Approximately half of the downregulated genes were MOF bound, whereas only a small proportion of genes upregulated in Mof-deleted MEFs were bound by MOF in embryonic stem cells. (h) Ki-67 expression analysis in Mof-deleted MEFs compared with controls. Mof deletion resulted in a significant reduction in Ki-67-positive cells. (i) β-Galactosidase activity, which is a marker for senescence, in Mof-deleted and control MEFs. Cells were treated with C12FDG, which fluoresces in the GFP channel once catalyzed by β-galactosidase, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Mof deletion had no effect on β-galactosidase activity. (j) Cell death rates in Mof-deleted MEFs compared with controls. Cell death was measured by propidium iodide (PI) incorporation. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Data were analyzed using analysis of variance, followed by a Student's t-test. Asterisks denote statistical significance at *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001. n=3 per genotype in (d–j).

Consistent with previous studies,14, 16 4-hydroxy tamoxifen-induced Mof deletion in Moffl/fl;Cre-ERT2T/+ cells lead to a complete failure of cell accumulation (Figure 1b, Supplementary Figure 1c). Although the importance of MOF in responding to DNA damage in proliferating cells has been widely studied,16, 18, 19, 20 whether other MOF-based mechanisms are required for cell cycle progression are currently unknown. To this end, we undertook gene expression analysis in early passage MEFs (Figure 1c, Supplementary Figure 2). Compared with controls, 1683 genes were significantly upregulated and 1683 downregulated in Mof-deleted MEFs (Figure 1d, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). To uncover which gene networks were regulated by MOF, we undertook GO term and KEGG pathway analyses. In both sets of analyses, ‘cell cycle' genes and ‘DNA replication' genes were most strongly affected (Figure 1e, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Interestingly, the majority of genes in the ‘cell cycle' group were strongly downregulated in Mof-deleted samples (Figure 1f). To test whether these differentially expressed genes were direct targets of MOF, we compared gene expression changes in Mof-deleted MEFs with those genes bound by MOF in embryonic stem cells,26 which represent another proliferative cell population. Interestingly, a significant proportion of cell cycle genes downregulated in Mof knockout MEFs appear to be associated with MOF (48%, Figure 1f, Supplementary Figure 4). This trend extended to all genes that were differentially expressed upon Mof deletion. Approximately half of all genes downregulated in Mof-deleted MEFs were bound by MOF in embryonic stem cells and human CD4 T cells, compared with only 11% of upregulated genes (Figure 1g, Supplementary Figure 3a). Together, these data suggest that in addition to the requirement for MOF in the DNA damage response, MOF binds directly to genes required for cell cycle progression and positively maintains their transcription.

It has previously been suggested that the genomic deletion of Mof by Cre-recombinase, or Mof depletion via small interfering RNA leads to the induction of cellular senescence.16, 22 In contrast, our gene expression and chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses suggest that MOF binds and activates genes required for cell cycle progression, suggesting that senescence maybe a secondary response in more aged or damaged cells. To clarify this apparent discrepancy, we undertook phenotypic analyses to determine the functional defects in Mof knockout MEFs. Consistent with the failure of Mof-deleted MEFs to accumulate (Figure 1b), a ninefold reduction in the number of cells expressing the proliferative Ki-67 marker was observed in Mof-deleted MEFs (Figure 1h). Interestingly, we did not observe an increase in the senescence markers β-galactosidase (Figure 1i, Supplementary Figures 1d and e), Arf or p21 (Supplementary Figure 1f). Only a modest increase in Ink4a mRNA was detected (Supplementary Figure 1f). In addition, the proportion of dead to live cells was increased modestly in Mof knockout MEFs (Figure 1j). However, this increase most likely reflects the lack of proliferation and accumulation of healthy MEFs in Mof knockout cultures, rather than an absolute increase in cell death. Together, our analyses of MEFs at steady state suggest that MOF directly binds and maintains the transcription of genes required for cell cycle progression.

MOF is dispensable in terminally differentiated, postmitotic podocytes under physiological conditions

In order to examine the cellular requirement for MOF in terminally differentiated cells, we focused on the function of MOF in glomerular podocytes. During kidney development, podocytes exit the cell cycle and are retained in the G0 phase after birth.27 Podocytes form the outer part of the kidney filtration barrier and are critical for the normal functioning of the kidney.28 Podocytes harbor foot processes, which along with the associated glomerular basement membrane and the endothelium of the capillaries form a filtration sieve. Podocyte cell death or damage that causes disruption of the foot processes, commonly referred to as podocyte effacement, leads to proteinuria, subsequent glomerulosclerosis and the onset of chronic kidney disease.29, 30

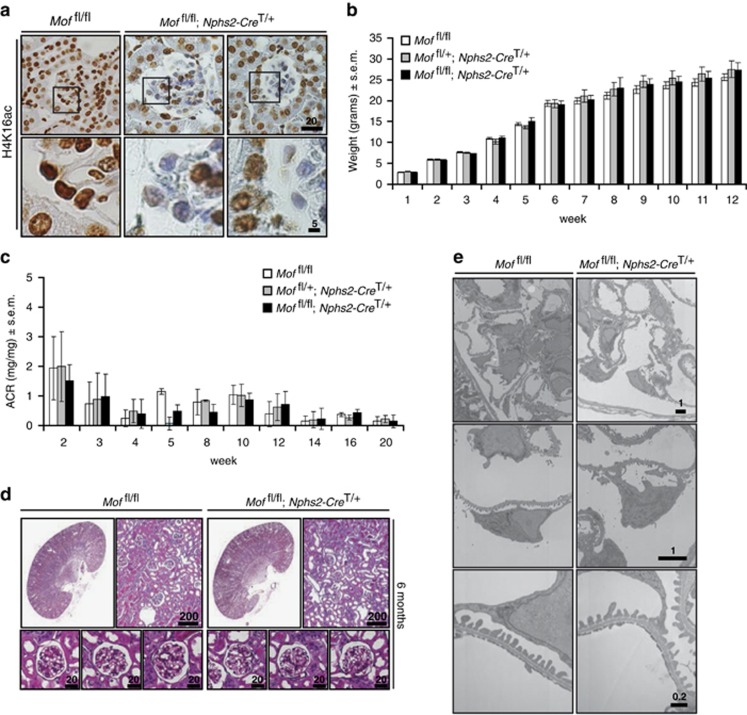

To induce Mof deletion specifically in podocytes, we crossed Mof floxed and Nphs2-CreT/+ mice. The Nphs2 promoter is activated at the late capillary loop stage of glomerular development, after podocytes have entered the G0 phase.31 In the absence of an adequate MOF antibody that detects endogenous MOF by immunohistochemistry, we used depletion of H4K16ac as a marker for Mof deletion. As evident in Figure 2a, H4K16ac levels were significantly reduced in Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ glomerular podocytes compared with controls. Intriguingly, deletion of Mof in podocytes had no effect on weight gain or kidney function of Moffl/fl;Nphs2T/+ mice over the first 20 weeks of life (Figures 2b and c). Furthermore, the overall kidney structure and podocyte morphology, as determined by conventional and electron microscopy, was normal in Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice until at least 6 months of age (Figures 2d and e). Our data suggest that MOF is not critical in terminally differentiated glomerular podocytes at steady state. This is particularly intriguing as all previous reports of Mof depletion in an array of cell types have lead to adverse outcomes.13, 14, 16, 17, 23, 24, 25

Figure 2.

MOF is dispensable from glomerular podocytes at steady state. (a) Immunohistochemical analysis of H4K16ac in mouse kidney sections of 6-month-old Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice and Moffl/fl littermate controls confirming loss of H4K16 acetylation in Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ podocytes. Scale bars are indicated in μm. (b) Weight gain dynamics of Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+, heterozygote Moffl/+;Nphs2-CreT/+ and Moffl/fl control mice (n=6 Moffl/fl, 5 Moffl/+;Nphs2-CreT/+, 4 Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+). (c) Urinary albumin/creatinine ratios (ACR) for Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice and littermate controls (n=6 Moffl/fl, 5 Moffl/+;Nphs2-CreT/+, 4 Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+). Mof deletion in podocytes did not have any effect on the ACR ratio at steady state. (d) Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining of kidney sections from 6 month old Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice and littermate Moffl/fl controls at steady state. No overt morphological defects were evident in Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ kidneys. Scale bars are indicated in μm. (e) Transmission electron microscopy of Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ kidney sections and littermate controls at steady state. No defects in podocyte structure or foot processes were observed in Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ samples. Scale bars are indicated in μm. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. and were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance followed by a Student's t-test.

Induced proliferation of podocytes requires MOF in ex vivo culture

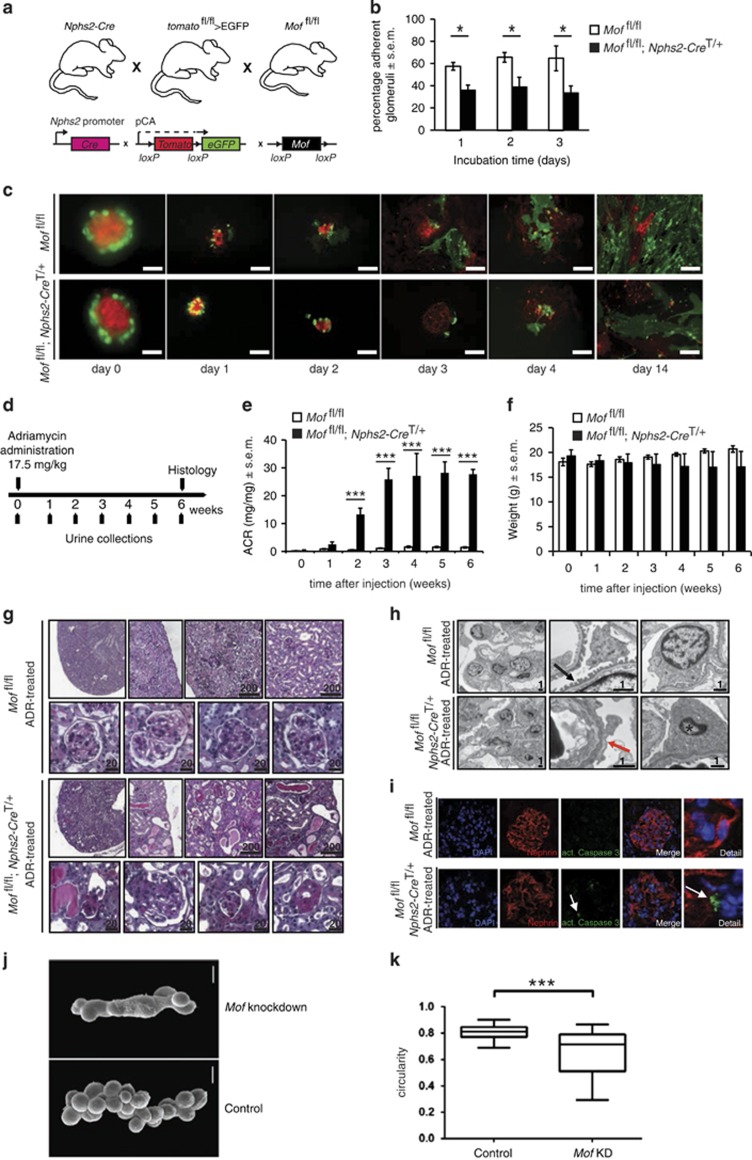

Our previous analyses have revealed that MOF is critical for cell cycle progression, but not for maintenance of differentiated podocytes. We wondered if MOF would also be critical in podocytes if they were artificially induced to enter the cell cycle. For this purpose, we crossed Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ and Tomatofl/fl;eGfp mice (Figure 3a). Tomatofl/fl;eGfp mice normally express Tomato, except when the Tomato locus is recombined by Cre-recombinase and eGfp expression activated. Therefore, in the presence of the Nphs2 transgene, enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) expression is induced specifically in podocytes.32 We isolated podocytes based on GFP expression by flow cytometry and placed cells in culture (Supplementary Figure 5). In contrast to controls, Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ podocytes showed significantly reduced proliferation over a 14-day culture period (Figures 3b and c). These data suggest that although MOF is not required at steady state in differentiated podocytes, it is nevertheless necessary for the accumulation of podocytes when placed ex vivo in culture.

Figure 3.

Mof deletion in glomerular podocytes results in an inability to respond to stress. (a) Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice were crossed with tomatofl/+>eGFP animals to produce Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+;tomatofl/+>eGFPT/+ progeny. Tomato is ubiquitously expressed in these mice, with the exception of podocytes, where the Nphs2-Cre splices out the Tomato and activates eGfp expression. (b) In vitro quantification of proliferating Mof-deleted and control glomeruli isolated from 10-day-old mice. Number of days of in vitro culture is indicated. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of isolated glomeruli from Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+;tomatofl/+>eGFP T/+ mice and littermate controls. Podocytes can be identified by eGFP expression. Scale bars equal 20 μm. (d) Experimental design of stress induction using Adriamycin. Mice were injected intravenously with 17.5 mg/kg Adriamycin. Albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) and body weight were measured one day before injection and then weekly up to 6 weeks after injection. (e) Urinary ACR after Adriamycin treatment of Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ and littermate Moffl/fl controls. n=39 mice per group. (f) Body weight of mice after a single shot of Adriamycin administered to Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ and littermate Moffl/fl controls. n=39 mice per group. (g) Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining of kidney sections from 12-week-old Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice and littermate controls 6 weeks after Adriamycin injection. Scale bars are indicated in μm. (h) Transmission electron microscopy of kidney sections from Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice 6 weeks after Adriamycin injection. Example of a pyknotic nucleus is marked with (*), black arrow indicates normal foot process, whereas red arrow indicates foot process with significant effacement. Scale bars are indicated in μm. (i) Kidney sections from Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice and littermate controls immunostained for Nephrin and activated caspase-3 6 weeks after Adriamycin injection. White arrows indicate positive staining of activated caspase-3. (j) Scanning electron micrographs of GCNs at third larval stage. Genotypes: control—sns-GCN-GAL4/+; Mof KD—sns-GAL4/UAS-Mof-RNAi. Scale bars equal 20 μm. (k) Quantitation of circularity revealing a significant loss of circularity upon RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated Mof knockdown. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Data were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance followed by a Student's t-test. Asterisks indicate significance at *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001.

MOF is required for podocyte maintenance under pathophysiological conditions

Although Mof-deleted podocytes were functionally and morphologically normal at steady state, we next wanted to determine the role of MOF under stress conditions. We used a well-established acute kidney injury model, which is induced through Adriamycin (doxorubicin) treatment and results in the activation of multiple stress response pathways.33 We challenged 6-week-old Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice and Moffl/fl controls with Adriamycin (Figure 3d). In contrast to Moffl/fl controls, Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice were unable to maintain normal kidney function, as documented by urine albumin levels, up to 6 weeks after a single injection of Adriamycin (Figures 3e and f). Consistently, histological and ultrastructural analyses revealed severe signs of glomerular and podocyte damage in Adriamycin-treated Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice (Figures 3g and h). In particular, Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice displayed significant glomerulosclerosis with tubular dilation, flattened tubular epithelium, tubular protein accumulation and segmental glomerular sclerosis compared with controls (Figure 3g). Furthermore, global foot process effacement with significantly increased foot process widths were observed in Adriamycin-treated Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice by electron microscopy (Figure 3h). Consistent with increased morphological deformities in kidneys from Adriamycin-treated Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice, pyknotic nuclei and activated caspase-3-positive cells were observed in Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ and not Moffl/fl control kidneys (Figures 3h and i). Together, these morphological and functional analyses reveal that in postmitotic podocytes, MOF is required to ensure functional maintenance and adaptation in response to injury.

MOF function in podocytes is conserved in Drosophila

MOF is highly conserved from Drosophila to mammals and has been identified as the major H4K16 KAT in these species.12, 13, 14, 15 Given the importance of MOF in murine podocytes, we investigated whether this function is conserved in other species. We analyzed the importance of MOF in Drosophila using the Garland cell nephrocytes (GCNs) as a test system. GCNs possess a number of features in common with mammalian podocytes,34 as well as with renal tubules,35 and essentially function as kidneys in Drosophila. We used the sns-GCN-Gal4 line for targeted expression of Mof-RNA interference starting at embryonic stage 13 and analyzed the cells at the third larval stage. Interestingly, RNA interference-mediated knockdown of mof resulted in highly defective, hyperfused and agglutinated GCNs (Figures 3j and k), suggesting that MOF is critical for kidney function across two very different species.

Mof depletion in podocytes leads to an enrichment for genes affected in kidney disease

Our work thus far has established that MOF is not required for maintenance of podocytes at steady state, but is critical for responding to stress. To investigate how MOF is required to respond to stress at the mechanistic level, we undertook genome-wide gene expression analysis. For this purpose, we cultured the MPC5 podocyte cell line,36 which possesses a temperature sensitive promoter driving the SV40 antigen. MPC5 podocytes are highly proliferative when cultured at 33°C and can be induced to differentiate when placed at 37 °C (Figure 4a). After inducing differentiation, MPC5 cells expressed known markers of podocytes including Nephrin and WT1 (Figure 4b). We infected differentiated MPC5 podocytes with a Mof short hairpin RNA and a Scramble control short hairpin RNA. After selection, a 75% reduction in Mof mRNA was observed in Mof knockdown samples compared with controls (Supplementary Figure 6). Both Mof-depleted and Scramble control samples were treated with Adriamycin and vehicle for 24 h (Figure 4a, Supplementary Figure 7), RNA was then isolated and processed for sequencing.

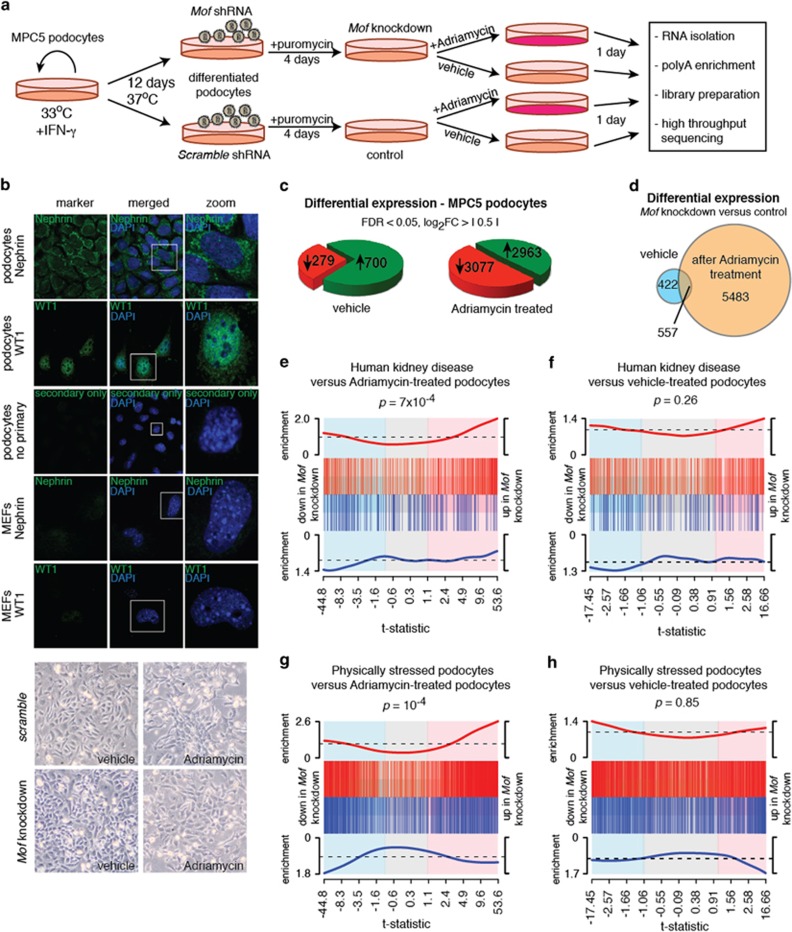

Figure 4.

Mof depletion in podocytes leads to an enrichment for genes deregulated in kidney disease. (a) Experimental outline depicting Mof short hairpin RNA depletion in differentiated MPC5 podocytes. MPC5 podocytes were expanded at 33 °C in the presence of interferon-γ (IFN-γ). To induce differentiation, IFN-γ was removed and cells maintained at 37 °C for 12 days. Differentiated podocytes were infected for 4 days with lentivirus containing a Mof knockdown and Scramble control vectors. After a 4-day selection period, podocytes were treated with Adriamycin (0.25 μg/ml) for 24 h and collected for RNA sequencing analysis. n=3 per treatment. (b) Immunofluoresence staining of differentiated MPC5 cells with podocyte markers Nephrin and WT1. MEFs, which do not express Nephrin and WT1, are provided as a negative control. Lower panel depicts bright-field images of Mof knockdown and Scramble controls treated with Adriamycin and vehicle. Mof depletion did not result in decreased cell viability. (c) Number of differentially expressed genes in Mof knockdown MPC5 podocytes compared with Scramble controls. Many more genes were significantly changed in Mof knockdown samples after Adriamycin treatment compared with vehicle control. (d) Overlap of genes misexpressed in Mof knockdown samples when treated with Adriamycin or vehicle. Only a small proportion of genes differentially expressed in Mof knockdown samples treated with Adriamycin were also differentially expressed in Mof knockdown podocytes treated with vehicle. (e, f) Barcode plot representing the comparison of gene expression changes during human kidney disease (GSE50892) with differential expression in Mof-depleted samples after Adriamycin (e) or vehicle (f) treatment. The pink shaded area represents genes significantly upregulated in Mof knockdown podocytes, whereas the blue shaded area represents genes significantly downregulated in Mof-depleted podocytes. Genes in the gray shaded area were unchanged in Mof knockdown samples compared with Scramble controls. Genes significantly upregulated (false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05) in the GSE50892 data set are represented with red bars, whereas genes downregulated in GSE50892 are represented with blue bars. The enrichment worm represents the extent to which the genes differentially expressed in the GSE50892 data set overlap with gene expression changes in the Mof knockdown data set. A cut-off of FDR <0.05 was applied to identify gene expression changes in the GSE50892 data set. (g, h) Comparison of gene expression changes in physically stressed (stretched) podocytes (GSE66336) with differentially expressed genes in Mof-depleted samples after Adriamycin (g) or vehicle (h) treatment.

Compared with Scramble controls, Mof knockdown podocytes displayed differential expression of 979 genes in vehicle-treated samples, whereas over 6000 genes were differentially expressed after Adriamycin treatment (Figure 4c, Supplementary Tables 5, 6 and 13). Interestingly, there was only a partial overlap between genes misexpressed in Mof knockdown samples treated with vehicle and Adriamycin (Figure 4d), suggesting that MOF is required to maintain normal transcriptional levels of a unique and much larger set of genes under Adriamycin-induced stress conditions.

We next compared gene expression changes because of the depletion of Mof with other published data sets. Glomerular abnormalities are common after orthotopic liver transplantation.37 Genes overexpressed in biopsies of damaged glomeruli (GSE50892, Broin, Akalin, de Boccardo) were also upregulated in Adriamycin-treated podocytes after Mof depletion (Figure 4e, P=7 × 10−4). Interestingly, this overlap between the Mof knockdown data set and biopsies of damaged glomeruli was confined to podocytes treated with Adriamycin, and was not observed in vehicle-treated podocytes (Figure 4f, P=0.26). Similarly, those genes overexpressed after administration of physical stretching stress38 as recently described (GSE66336),39 were also overexpressed in Mof-depleted podocytes after Adriamycin administration (P=10−4) and not vehicle treatment (Figures 4g and h, P=0.85). Together, these data suggest that in the absence of Mof, gene expression changes in podocytes resemble those seen in stressed podocytes or diseased human kidney samples.

MOF maintains transcription of genes required in lysosomes, endocytosis and vacuoles

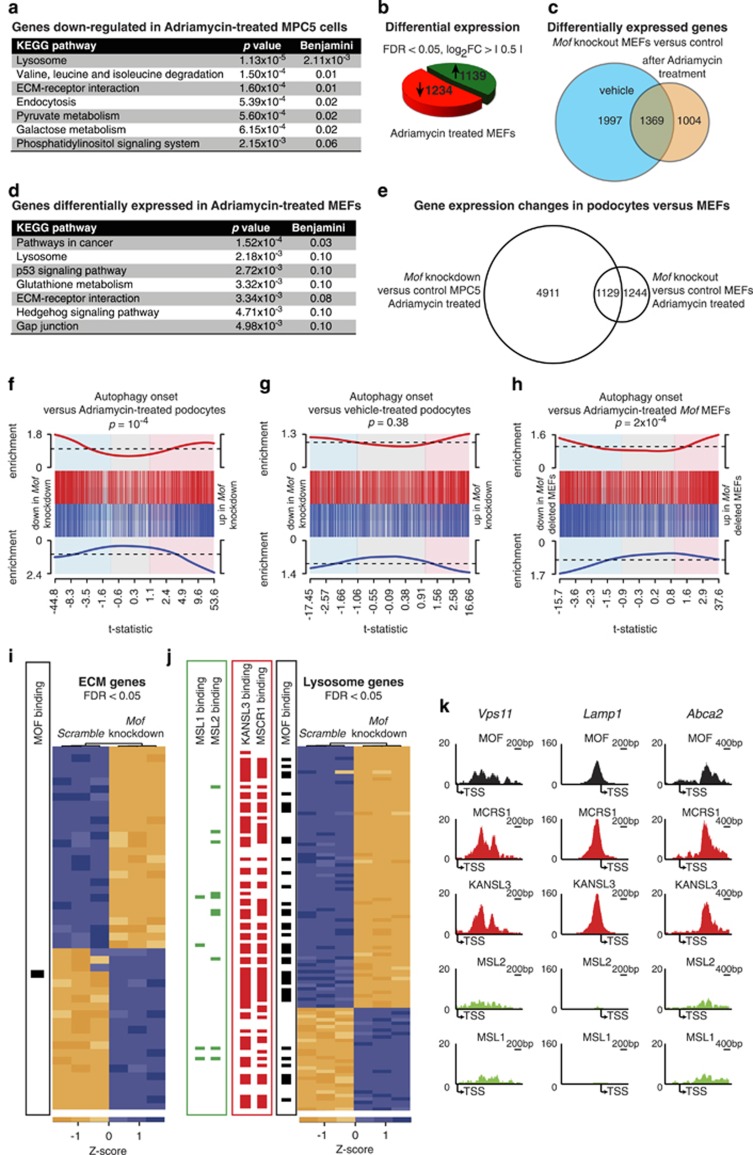

To further investigate which cellular networks could be regulated by MOF, we undertook KEGG pathway and gene ontology analysis (Supplementary Tables 7-12 and 14-18). To focus on direct targets of MOF, we separated downregulated genes from upregulated genes in Mof knockdown podocytes. In MPC5 podocytes, the pathways most significantly downregulated were ‘lysosome', ‘valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation', ‘extracellular matrix–receptor interaction' and ‘endocytosis' (Figure 5a, Supplementary Figures 8 and 9). Similarly, gene ontology analysis for the most enriched cellular compartments returned ‘vacuole', ‘lysosome', ‘lytic vacuole' and ‘organelle membrane' (Supplementary Table 15).

Figure 5.

MOF is required to maintain transcription of genes involved in lysosomes, endocytosis and vacuole function under stress conditions. (a) KEGG pathway analysis of genes downregulated in Mof-depleted MPC5 podocytes. A Benjamani cut-off of 0.10 was applied. (b) Number of genes differentially expressed in 4-hydroxy tamoxifen (4OHT)-treated Moffl/fl;Cre-ERT2T/+ MEFs compared with Moffl/fl controls after administration of Adriamycin for 24 h. A cut-off of FDR <0.05 and absolute log2(fold change)>0.5 was used. n=3 independent sex and litter-matched MEF lines per genotype. (c) Venn diagram depicting genes differentially expressed in Mof knockout MEFs compared with controls after Adriamycin and vehicle treatment. (d) KEGG pathway analysis of genes differentially expressed in 4OHT-treated Moffl/fl;Cre-ERT2T/+ MEFs compared to controls. A Benjamani cut-off of 0.10 was applied. (e) A comparison of gene expression changes (Venn diagram) in Mof-depleted MPC5 podocytes and Mof knockout MEFs after treatment with adriamycin. Approximately threefold more genes were misexpressed after Adriamycin treatment in Mof-depleted MPC5 podocytes compared with Mof-deleted MEFs. A significance cut-off of FDR <0.05 and absolute log2(fold change)>0.5 was applied. (f-h) Comparison of gene expression changes observed during RasV12 induced autophagy40 (GSE28464) with Mof knockdown samples treated with (f) Adriamycin and (g) vehicle, as well as Mof-deleted MEFs treated with (h) Adriamycin. Genes in the GSE28464 data set were considered upregulated (red bars) or downregulated (blue bars) if they passed the FDR cut-off of 0.05. Note the opposing enrichments in Mof-depleted podocytes treated with Adriamycin, which show an inverse relationship with genes expression changes during autophagy (f), and Mof knockout MEFs treated with Adriamycin, which show a positive correlation with gene expression changes observed in autophagy (h). (i) A heat map showing expression levels of ‘extracellular matrix' genes (KEGG database), differentially expressed in Mof-depleted MPC5 podocytes (FDR<0.05). The heat map displays normalized counts per gene in each of the three replicates. Only one differentially expressed gene was bound by MOF (shown in black). (j) Heat map representing differentially expressed ‘lysosome' genes in Mof-depleted MPC5 podocytes compared with controls (FDR <0.05). A significant proportion of genes showing lower mRNA expression in Mof knockdown samples showed MOF binding. The MOF-bound genes showed overlap with binding of non-specific lethal (NSL) complex members (KANSL3, MCRS1, red) and not male-specific lethal (MSL) complex members (MSL1, MSL2, green). See also Supplementary Figure 10. (k) Depictions of lysosome-related genes Vps11, Lamp1 and Abca2 showing strong binding of MOF, as well as NSL complex members MCRS and KANSL3, but not MSL members MSL1 and MSL2. bp, base pairs; FDR, false discovery rate; TSS, transcriptional start site.

To determine if MOF was required for a similar response in MEFs, we treated Moffl/fl control and Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ MEFs with 4-hydroxy tamoxifen followed by Adriamycin for 24 h and undertook RNA sequencing analysis. Compared with controls, 2373 genes were differentially expressed in Adriamycin-treated Mof-deleted MEFs (Figures 5b and c, Supplementary Tables 19 and 20). Interestingly, the most affected pathways in Mof-deleted MEFs also included ‘lysosome' and ‘extracellular matrix–receptor interaction', in addition to ‘pathways involved in cancer' and the ‘p53 pathway', which reflects the proliferative nature of MEFs (Figure 5d). Reminiscent of podocytes, the three most highly enriched gene ontology terms in the MEF data set were also ‘lysosome', ‘lytic vacuole' and ‘vacuole' (Supplementary Table 22). This overlap between the most highly affected pathways in stressed Mof-deleted MEFs and Mof knockdown podocytes occurred despite only a modest overlap in gene expression changes between MEFs and podocytes (Figure 5e).

Our analyses revealed that the most common pathways affected by the loss of MOF were the lysosome, vacuole and endocytosis pathways. These three pathways have been identified as key components of autophagy.40 We therefore compared gene expression changes upon depletion of Mof and onset of autophagy. Interestingly, gene expression changes in Mof-depleted Adriamycin-treated podocytes showed a strong negative correlation with genes activated during autophagy. Indeed, genes normally activated during autophagy (GSE28464)40 were expressed at low levels in Mof-deficient podocytes (Figure 5f, P=10−4). This relationship was only observed after Adriamycin treatment and not after vehicle treatment (Figure 5g, P=0.38). This is consistent with the fact that autophagy has a strong protective role in models of kidney disease.41, 42, 43, 44, 45 In contrast to podocytes, an opposing relationship was observed in Adriamycin-treated Mof-deleted MEFs, whereby genes normally activated during autophagy were also upregulated in Mof knockout MEFs (Figure 5h, P=2 × 10−4). This disparity between MEFs and podocytes most likely reflects the inherent differences in cell type and function, and further underscores the hypothesis that MOF acts in a context-dependent manner.

MOF maintains transcription of lysosomal, endocytosis and vacuole genes via the non-specific lethal and not male-specific lethal complex

MOF is found in two distinct complexes, the male-specific lethal (MSL) and non-specific lethal (NSL) complexes, in both mammals and Drosophila.15, 26, 46, 47, 48 We investigated whether MOF directly targeted promoters of genes in the lysosome, endocytosis and vacuole pathways and whether it did so via the MSL or NSL complex. We focused on gene expression changes in podocytes, where the above pathways are known to have a protective role in disease. Foremost, we investigated the extracellular matrix genes, which were significantly downregulated in Adriamycin-treated Mof knockdown podocytes (Figure 5a). We obtained the complete list of extracellular matrix genes from the KEGG database. Only one of these genes was bound by MOF in embryonic stem cells26 (Figure 5i), suggesting that changes in gene expression in this pathway are a secondary effect and not a direct consequence of Mof depletion. In contrast, lysosome, endocytosis and vacuole sets of genes, which were significantly downregulated in Mof-depleted, Adriamycin-treated podocytes, showed a significant enrichment for MOF binding (Figure 5j, Supplementary Figure 10). Strikingly, the MOF-bound genes overlapped with binding of NSL complex members KANSL3 and MCRS1, but not MSL complex members MSL1 and MSL2 (ref. 26) (Figures 5j and k, Supplementary Figure 10). These data reveal that MOF is likely to maintain the transcription of genes required in the lysosome, endocytosis and vacuole pathways via the NSL complex.

MOF depletion results in endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi and nuclear structure defects under stress conditions

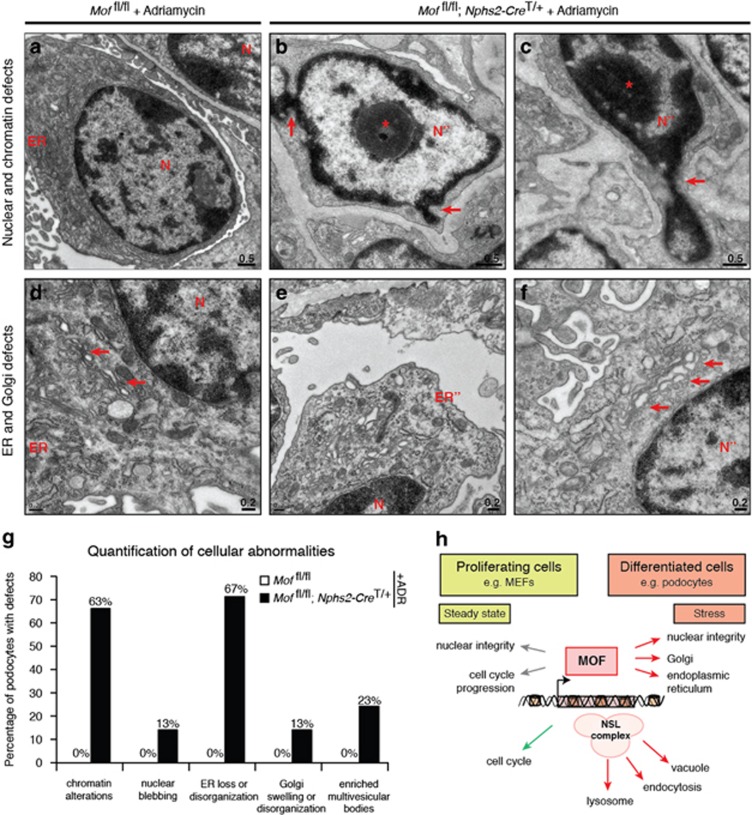

The endocytosis and lysosome pathways involve vesicular transport. Given the transcriptional defects under stress conditions in these pathways because of Mof depletion, we hypothesized that gross cellular defects in organelles that participate in vesicular transport would also be present. In addition, we wanted to investigate chromatin structure, as approximately 6000 genes were deregulated after Adriamycin treatment in Mof knockdown podocytes. For this reason, we undertook electron microscopy studies of podocytes from Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ and Moffl/fl control mice after Adriamycin treatment. Strikingly, we observed severe chromatin condensation defects in 63% of Mof-deleted podocytes (n=83 podocytes), but not in controls (Figures 6a and c, defects marked with N', Figure 6g). In addition, a severe nuclear blebbing phenotype was evident in 13% of all podocytes (arrows in Figures 6b, c and g). Intriguingly, a significant disorganization and in many cases loss of ER was observed in 67% of glomerular podocytes from Adriamycin-treated Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice (compare ER in Figures 6d, e and g). Consistently, severe Golgi defects were observed in 13% of podocytes (arrows in Figures 6d versus f), whereas abnormal accumulation of multivesicular bodies was observed in 23% of Mof-deleted podocytes (Figure 6g). Together, these analyses strongly correlate with our mechanistic analysis and highlight the importance of MOF in maintaining nuclear structure, which is closely related to transcriptional regulation, as well as the ER and Golgi organelles that are critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Figure 6.

Mof deletion results in ER, Golgi, chromatin and nuclear structure defects in vivo in response to cellular stress. (a) Podocyte from Moffl/fl mice after Adriamycin treatment. Note normal nuclear and ER structure. (b, c) Podocytes from Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice after Adriamycin treatment. Abnormal chromatin, as well as nuclear blebbing (marked with red arrows) can be clearly observed in nuclei (marked N'). (d) Moffl/fl podocyte showing a well-established ER system and Golgi cisternae (arrows). (e) Example of ER loss, as well as disorganization of the remaining ER system (marked ER') in a podocyte from Moffl/fl;Npsh2-CreT/+ mice. (f) Depiction of irregular Golgi apparatus showing swelling in a podocyte from Moffl/fl;Npsh2-CreT/+ mice after Adriamycin treatment. (g) Quantification of nuclear, ER and Golgi defects in podocytes isolated from Moffl/fl and Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+ mice (n=83 podocytes) after Adriamycin treatment. (h) A summary model of new MOF functions established during this study. We show the importance of MOF under stress conditions in maintaining the ER, Golgi and nuclear integrity, as well as transcription of genes in the lysosome, vacuole and endocytosis pathways. These are shown in red. Under steady state, it was previously established that MOF is required for cell cycle progression and maintaining nuclear integrity (gray). We show here that MOF directly maintains the transcription of genes required for cell cycle progression (green). All scale bars are presented in μm. Arrows in (b) and (c) mark abnormal nuclear blebbing. Arrows in (d) and (f) mark the Golgi. Double apostrophes indicate abnormal structures. Asterisk in (b) and (c) mark the nucleolus. N, nucleus.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the importance of MOF in responding to cellular stress in the context of proliferating and terminally differentiated cells. We find that MOF is required for cell cycle progression in MEFs and cultured podocytes. Indeed, we uncover that MOF binds directly to genes required for cell cycle progression and maintains their transcription. Although MOF was dispensable for the maintenance of postmitotic glomerular podocytes at steady state, MOF appeared to be a key regulator of podocyte stress response and adaptation. At a mechanistic level, MOF was required in podocytes to maintain transcription of genes of the lysosome, endocytosis and vacuole pathways, which are key regulators of cellular homeostasis in podocytes43, 49 and other cells (Figure 6h). Together, our work establishes a novel role for MOF in maintaining cellular homeostasis in response to stress.

An efficient cellular response is needed for ensuring that homeostasis within a cell is maintained and stress does not induce overt damage and eventually cell death.50 The importance of MOF in responding to stress has been particularly well studied in the context of induced DNA damage. Following DNA damage, there is normally an increase in H4K16ac.16 In the absence of MOF, DNA response proteins including MDC1, 53BP1 and BRCA1 are not recruited to DNA damage foci in a timely manner.16, 22 The response to DNA damage is at least partially imparted by the interaction between MOF and the ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase,18, 19 whereby the ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase phosphorylates MOF at T392.18 This process is particularly important for DNA damage repair in the S, G2 and M phases of the cell cycle,18 and potentially explains the observed G2/M cell cycle arrest in Mof knockout cells. Although the importance of MOF in responding to DNA damage, especially in proliferating cells is well studied,14, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 there are currently no reports investigating the importance of MOF in responding to stress in non-proliferating cells. Here, we provide strong evidence that MOF is required to maintain the lysosome, endocytosis and vacuole pathways, as well as the ER, Golgi and nuclear structure in response to stress. This is particularly true for postmitotic, long-lived podocytes, where alterations in each of these pathways directly underlies the susceptibility to acquired and genetic diseases.43, 49, 51, 52, 53 Although our study provides clear evidence for the importance of MOF in the transcriptional regulation of organelle pathways in podocytes, an additional direct role for MOF in maintaining non-nuclear organelles needs to be addressed in the future.

Chronic kidney disease encompasses a set of debilitating diseases whose incidence is rising in the Western world, especially in elderly individuals. Hallmarks of chronic kidney disease include glomerulosclerosis, inflammation and fibrosis, and are associated with the continuous loss of kidney parenchyma and functional nephrons.29, 30 The kidney normally compensates for this loss by demanding further work from remaining glomeruli, which in turn induces further stress on these components of the kidney. In this study, we found that Mof deletion in podocytes had no adverse functional side effects at steady state at least on a pure C57BL/6 background. However, once low-level damage was induced through Adriamycin administration, Mof-deleted podocytes were not able to cope with the added stress. Our mechanistic analyses revealed that this was in part because of the inability of Mof-deleted podocytes to activate components of the lysosome, vacuole and endocytosis pathways. Interestingly, these three pathways have a key role in autophagy.40 A large body of literature has recently shown the importance of autophagy in protecting kidney cells including podocytes from damage.41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 54 Strikingly, Mof deletion in podocytes phenocopies the effects of autophagy-deficient podocytes in terms of the markedly increased susceptibility toward Adriamycin,43 suggesting that at least in the context of podocytes, MOF is critical for activating part of the autophagy response in reply to cellular stress. Intriguingly, we found that autophagy-related genes were expressed in opposing directions in Adriamycin-treated Mof-deficient podocytes and MEFs. This is likely due to inherent differences between the two cell types. Although autophagy is required to protect against kidney disease,41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 54 autophagy becomes activated in fibroblasts once they come senescent, or once senescence is induced.55 Consistently, it has recently been suggested that downregulation of MOF and H4K16ac are critical for MEFs to induce autophagy and avoid cell death.56 Together with our results, these observations suggest that MOF has a highly context-specific role and is required for different functions depending on the particular circumstances.

In summary, this study provides evidence for MOF-dependent cell-specific regulation of stress adaptive gene regulatory networks. In postmitotic podocytes, MOF directly contributes to the maintenance of the lysosome, endosome and vacuole systems in response to stress, whereas in fibroblasts and undifferentiated podocytes, MOF drives cell cycle progression. Taken together, our work uncovers a novel and critical context-specific role for MOF in protecting cells against cellular stress.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal studies and experimental procedures were performed according to the German animal care and ethics legislation and had been approved by the local government authority, the Committee on Research Animal Care, Regierungspräsidium Freiburg (G11/51 and X10/10H). The Moffl/fl (ref.13) and Nphs2-Cre mice57 strains have been previously described. Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J and Cre-ERT2 mice were sourced from the Jackson Laboratory (JAX, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 background, kept under a 12-h light and dark cycle, and water and standard chow were available ad libitum. Drosophila melanogaster stocks were maintained on standard cornmeal molasses agar food at 25 °C. Experiments were performed at 29 °C for maximal efficiency of the GAL4/UAS-System. Sns-GCN-GAL4 (gift from Susan Abmayr) was used for targeted expression of UAS-Mof-RNA interference (VDRC TiD 105370).

Conditional Mof depletion in MEFs

MEFs were cultured from embryonic day (E)13.5 Moffl/fl and Moffl/fl;Cre-ERT2T/+ embryos as described previously.58 MEFs were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GlutaMax supplement, Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% fetal calf serum. To induce Mof deletion, MEFs were cultured in presence of 200 nM 4-hydroxy tamoxifen (Sigma T176, Seelze, Germany) for 3.5 days.

Cell proliferation, viability and senescence assays

For ki-67 detection, MEFs were fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences, 554714, Heidelberg, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated Ki-67 antibody overnight at 4°C (BD Biosciences, 556026), washed and analyzed by flow cytometry (LSRII, BD, Heidelberg, Germany). Viability was determined by analyzing propidium iodide (1 μg/ml) incorporation. Cells staining positive for propidium iodide were considered dead. Chromogenic and flow cytometric analyses of senescence were carried out as described by Debacq-Chainiaux et al.59 Gene expression analyses by quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR were carried out as described previously.58

Adriamycin-induced renal injury model

To induce progressive glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial inflammation, 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice received a single intravenous injection of 17.5 mg/kg Adriamycin at day 0.43 Urine albumin concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Mikrofluoral Mikroalbumin Test, Progen, Heidelberg, Germany). Urinary creatinine was quantitated spectrophotometrically with a commercially available kit (Creatinine PAP LT-SYS, Eberhard Lehmann GmbH, Berlin, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Renal morphology

Tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, 4 μm coronal sections were stained with periodic acid–Schiff reagent and analyzed with an Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For electron microscopy, mice were perfused transaortically with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.05% glutaralaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. In all, 50 μm sections were cut on a vibratome and cryoprotected in a solution containing 25% sucrose and 10% glycerol in 50 mM phosphate-buffered saline. Ultrathin sections were then cut, fixed using Bouin solution, dehydrated and incubated in 100% hexamethyldisilazane. After dehydration, samples were coated with gold using a Polaron Cool Sputter Coater E 5100 (Quorum Technologies, Laughton, UK). Samples were imaged using a Leo 1450 VP electron microscope (Zeiss).

Immunofluorescence and western blot analysis

Kidneys were snap frozen in cryogenic Tissue-Tek OCT compound and 6 μm sections were prepared. Kidney sections and differentiated MPC5 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated for 1 h with primary antibodies raised against H4K16ac (Millipore, 07-329, Darmstadt, Germany), nephrin (Abcam, ab58968, Cambridge, UK), activated caspase 3, Nphs2 (Abcam, ab50339), WT1 (Santa Cruz, sc-192, Dallas, TX, USA) and podocin (Santa Cruz, sc-21009). After washing, fluorophore-conjugated Alexa secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) were applied for 30 min. Western blot was undertaken using standard procedures probing with antibodies raised against MOF (Bethyl, A300-992A, Montgomery, TX, USA), H4K16ac (Millipore, 07-329) and histone H3 (Active Motif, 39163, La Hulpe, Belgium).

Isolation of mouse glomeruli

Kidneys dissected from 10-day-old triple transgenic Moffl/fl;Nphs2-CreT/+;tomatofl/+>eGFP and littermate control mice were minced into 1-mm3 pieces and treated with 3 ml enzymatic digestion buffer (300 U/ml collagenase, 1 mg/ml pronase E, 50 U/ml DNase I) at 37 °C for 15 min. The digested kidneys were pressed through cell strainers with decreasing pore sizes (100, 70 and 40 μm) and washed extensively with Hank's balanced salt solution. Cells were collected by centrifugation, re-suspended in 0.5 ml of Hank's balanced salt solution supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin plus 4'6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1 μg/ml) before fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Collected podocytes were cultured in collagen IV-coated tissue culture flasks (Nunc) in RPMI medium supplemented with penicillin–streptomycin, fetal calf serum and insulin–transferrin–sodium selenite supplement (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland) at 37 °C in 95% O2 and 5% CO2.

MPC5 cell culture

MPC5 podocytes were cultured as described previously.36 Differentiation was induced at 37 °C over 12 to 14 days. Knockdown of Mof was carried out as previously described.26

RNA sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation-seq analysis

Mof knockout MEFs and differentiated Mof-depleted MPC5 podocytes along with the appropriate controls were treated with either vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide) or Adriamycin for 24 h (Supplementary Figure 7, MEFs—0.10 μg/ml, podocytes 0.25 μg/ml). RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) and sequenced on the Illumina Hi-Seq. 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Approximately 20 million pair-ended reads were obtained for each sample (Supplementary Table 1). Reads were mapped to the mouse genome (GRCm38) using the Tophat (v2.0.13)60 aligner and counted for Ensembl transcripts (release 78) using featureCounts (v1.4.5-p1).61 Differential gene expression levels were determined using DESeq2 (v1.4.1).62 Genes were considered significantly different at a cut-off false discovery rate value of 0.05 and an absolute log2 fold change of >0.5. GO term and KEGG pathway analyses were carried out using the DAVID platform.63 For gene set enrichment analyses, the Limma64 package was utilized (v3.20.1). Counts were transformed into a log2 per-million-counts using Voom65 and statistical significance determined using Roast66 as previously described.67 Data sets as indicated in the text were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Barcode plots were generated as described.67 Comparison of RNA-seq data set obtained in this study with chromatin immunoprecipitation-seq was performed using a comprehensive chromatin binding profiling data set obtained from Chelmicki et al.26 All data were deposited under the GEO ID GSE70707.

Acknowledgments

We thank K Lam, M Shvedunova and A Chatterjee for helpful discussions. We are grateful for the assistance provided by P Kindle (MPI-IE, Imaging facility) and B Joch (University Freiburg). BNS is supported by a Humboldt postdoctoral fellowship, WBW by a Marie Curie Career Integration Grant and a Margarete von Wrangell Habilitations-Stipendium. AKV and TT were supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, operational infrastructure grants from the Australian Federal Government (IRISS) and the Victorian State Government (OIS). TBH was supported by the DFG (Heisenberg program and CRC992 and CRC1140) and the European Research Council (ERC grant). AA is supported by the DGF CRC1140, CRC992 and CRC746. AA and TBH are part of the BIOSS II (Freiburg), the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

Supplementary Material

References

- Allfrey VG, Mirsky AE. Structural modifications of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Science 1964; 144: 559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh BN. Crafting the brain - role of histone acetyltransferases in neural development and disease. Cell Tissue Res 2014; 356: 553–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Naruse I, Hongo T, Xu M, Nakahata T, Maekawa T et al. Extensive brain hemorrhage and embryonic lethality in a mouse null mutant of CREB-binding protein. Mech Dev 2000; 95: 133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao TP, Oh SP, Fuchs M, Zhou ND, Ch'ng LE, Newsome D et al. Gene dosage-dependent embryonic development and proliferation defects in mice lacking the transcriptional integrator p300. Cell 1998; 93: 361–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper LH, Fukuyama T, Biesen MA, Boussouar F, Tong C, de Pauw A et al. Conditional knockout mice reveal distinct functions for the global transcriptional coactivators CBP and p300 in T-cell development. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 789–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Fukuyama T, Ney PA, Wang D, Rehg J, Boyd K et al. Global transcriptional coactivators CREB-binding protein and p300 are highly essential collectively but not individually in peripheral B cells. Blood 2006; 107: 4407–4416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau PM, Kim JC, Lu JT, Schwartzentruber JA, Abdul-Rahman OA, Schlaubitz S et al. Mutations in KAT6B, encoding a histone acetyltransferase, cause Genitopatellar syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 90: 282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Voss AK, Chowdhury K, Gruss P. Querkopf, a MYST family histone acetyltransferase, is required for normal cerebral cortex development. Development 2000; 127: 2537–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson MA, Deshpande C, Dafou D, Vissers LE, Woollard WJ, Holder SE et al. De novo mutations of the gene encoding the histone acetyltransferase KAT6B cause Genitopatellar syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 90: 290–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merson TD, Dixon MP, Collin C, Rietze RL, Bartlett PF, Thomas T et al. The transcriptional coactivator Querkopf controls adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 11359–11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss AK, Thomas T. MYST family histone acetyltransferases take center stage in stem cells and development. BioEssays 2009; 31: 1050–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar A, Becker PB. Activation of transcription through histone H4 acetylation by MOF, an acetyltransferase essential for dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol Cell 2000; 5: 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Dixon MP, Kueh AJ, Voss AK. Mof (MYST1 or KAT8) is essential for progression of embryonic development past the blastocyst stage and required for normal chromatin architecture. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28: 5093–5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale M, Rea S, Richter K, Vilar A, Lichter P, Imhof A et al. hMOF histone acetyltransferase is required for histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 6798–6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Cayrou C, Huang R, Lane WS, Cote J, Lucchesi JC. A human protein complex homologous to the Drosophila MSL complex is responsible for the majority of histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 9175–9188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Corsa CA, Pan PW, Wu L, Ferguson D, Yu X et al. MOF and H4 K16 acetylation play important roles in DNA damage repair by modulating recruitment of DNA damage repair protein Mdc1. Mol Cell Biol 2010; 30: 5335–5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Li L, Pandey R, Byun JS, Gardner K, Qin Z et al. The histone acetyltransferase MOF is a key regulator of the embryonic stem cell core transcriptional network. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 11: 163–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Hunt CR, Hegde ML, Chakraborty S, Udayakumar D, Horikoshi N et al. MOF phosphorylation by ATM regulates 53BP1-mediated double-strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Rep 2014; 8: 177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Sharma GG, Young CS, Agarwal M, Smith ER, Paull TT et al. Involvement of human MOF in ATM function. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 5292–5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma GG, So S, Gupta A, Kumar R, Cayrou C, Avvakumov N et al. MOF and histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16 are critical for DNA damage response and double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol 2010; 30: 3582–3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra MP, Horikoshi N, Pushpavallipvalli SN, Sarkar A, Bag I, Krishnan A et al. The role of MOF in the ionizing radiation response is conserved in Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma 2012; 121: 79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Chow MZ, Wang Z, Zhang L, Liu B, Liu X et al. Histone H4 lysine 16 hypoacetylation is associated with defective DNA repair and premature senescence in Zmpste24-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 12325–12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Guerin-Peyrou TG, Sharma GG, Park C, Agarwal M, Ganju RK et al. The mammalian ortholog of Drosophila MOF that acetylates histone H4 lysine 16 is essential for embryogenesis and oncogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28: 397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Hunt CR, Pandita RK, Pae J, Komal K, Singh M et al. T-cell-specific deletion of Mof blocks their differentiation and results in genomic instability in mice. Mutagenesis 2013; 28: 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Hunt CR, Gupta A, Nannepaga S, Pandita RK, Shay JW et al. Purkinje cell-specific males absent on the first (mMof) gene deletion results in an ataxia-telangiectasia-like neurological phenotype and backward walking in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 3636–3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelmicki T, Dundar F, Turley MJ, Khanam T, Aktas T, Ramirez F et al. MOF-associated complexes ensure stem cell identity and Xist repression. eLife 2014; 3: e02024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liapis H, Romagnani P, Anders HJ. New insights into the pathology of podocyte loss: mitotic catastrophe. Am J Pathol 2013; 183: 1364–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkkoetter PT, Ising C, Benzing T. The role of the podocyte in albumin filtration. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013; 9: 328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz W, Gretz N, Lemley KV. Progression of glomerular diseases: is the podocyte the culprit? Kidney Int 1998; 54: 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Shankland SJ. Podocyte biology and response to injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13: 3005–3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell C, Wanner N, Huber TB. Glomerular development - shaping the multi-cellular filtration unit. Sem Cell Dev Biol 2014; 36: 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerries M, Grahammer F, Eiselein S, Buck M, Meyer C, Goedel M et al. Molecular fingerprinting of the podocyte reveals novel gene and protein regulatory networks. Kidney Int 2013; 83: 1052–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VW, Harris DC. Adriamycin nephropathy: a model of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrology 2011; 16: 30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weavers H, Prieto-Sanchez S, Grawe F, Garcia-Lopez A, Artero R, Wilsch-Brauninger M et al. The insect nephrocyte is a podocyte-like cell with a filtration slit diaphragm. Nature 2009; 457: 322–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Zhao Y, Chao Y, Muir K, Han Z. Cubilin and amnionless mediate protein reabsorption in Drosophila nephrocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 209–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Reiser J, Zuniga Mejia Borja A, Pavenstadt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W et al. Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp Cell Res 1997; 236: 248–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Akalin E, Dikman S, Gagliardi R, Schiano T, Bromberg J et al. The variable pathology of kidney disease after liver transplantation. Transplantation 2010; 89: 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endlich N, Kress KR, Reiser J, Uttenweiler D, Kriz W, Mundel P et al. Podocytes respond to mechanical stress in vitro. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal A, Giebel J, Warsow G, Li L, Ummanni R, Schordan S et al. Mechanical stress enhances CD9 expression in cultured podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015; 308: F602–F613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Young AR, Arakawa S, Samarajiwa SA, Nakashima T, Yoshida S et al. Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science 2011; 332: 966–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Wei Q, Dong G, Komatsu M, Su Y, Dong Z. Autophagy in proximal tubules protects against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 1271–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takabatake Y, Kimura T, Takahashi A, Isaka Y. Autophagy and the kidney: health and disease. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant 2014; 29: 1639–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartleben B, Godel M, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Liu S, Ulrich T, Kobler S et al. Autophagy influences glomerular disease susceptibility and maintains podocyte homeostasis in aging mice. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 1084–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cina DP, Onay T, Paltoo A, Li C, Maezawa Y, De Arteaga J et al. Inhibition of MTOR disrupts autophagic flux in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GM, Gomez H, Collage RD, Loughran P, Zhang X, Escobar DA et al. Augmenting autophagy to treat acute kidney injury during endotoxemia in mice. PloS One 2013; 8: e69520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Jin J, Swanson SK, Cole MD, Choi SH, Florens L et al. Subunit composition and substrate specificity of a MOF-containing histone acetyltransferase distinct from the male-specific lethal (MSL) complex. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 4268–4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendjan S, Taipale M, Kind J, Holz H, Gebhardt P, Schelder M et al. Nuclear pore components are involved in the transcriptional regulation of dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol Cell 2006; 21: 811–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja SJ, Charapitsa I, Conrad T, Vaquerizas JM, Gebhardt P, Holz H et al. The nonspecific lethal complex is a transcriptional regulator in Drosophila. Mol Cell 2010; 38: 827–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JJ, Huber TB, Godel M, Jarad G, Hartleben B, Kwoh C et al. Albumin-associated free fatty acids induce macropinocytosis in podocytes. J Clin Invest 2015; 125: 2307–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S, Gorman AM, Hori O, Samali A. Cellular stress responses: cell survival and cell death. Int J Cell Biol 2010; 2010: 214074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir O, Jasiek M, Henique C, Guyonnet L, Hartleben B, Bork T et al. Endothelial cell and podocyte autophagy synergistically protect from diabetes-induced glomerulosclerosis. Autophagy 2015; 11: 1130–1145 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel W, Helmstadter M, Balica J, Hartleben B, Kiefer B, Hrnjic F et al. Vps34 deficiency reveals the importance of endocytosis for podocyte homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 727–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JM, Okamura K, Wakashin H, McFann K, Dobrinskikh E, Kopp JB et al. Podocytes degrade endocytosed albumin primarily in lysosomes. PloS One 2014; 9: e99771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber TB, Edelstein CL, Hartleben B, Inoki K, Jiang M, Koya D et al. Emerging role of autophagy in kidney function, diseases and aging. Autophagy 2012; 8: 1009–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AR, Narita M, Ferreira M, Kirschner K, Sadaie M, Darot JF et al. Autophagy mediates the mitotic senescence transition. Genes Dev 2009; 23: 798–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullgrabe J, Lynch-Day MA, Heldring N, Li W, Struijk RB, Ma Q et al. The histone H4 lysine 16 acetyltransferase hMOF regulates the outcome of autophagy. Nature 2013; 500: 468–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller MJ, Sanden SK, Soofi A, Wiggins RC, Holzman LB. Podocyte-specific expression of cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis 2003; 35: 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh BN, Phipson B, El-Saafin F, Vanyai HK, Downer NL, Bird MJ et al. MOZ (MYST3, KAT6A) inhibits senescence via the INK4A-ARF pathway. Oncogene 2015, e-pub ahead of print 16 March 2015; doi:10.1038/onc.2015.33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Debacq-Chainiaux F, Erusalimsky JD, Campisi J, Toussaint O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protocols 2009; 4: 1798–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 2013; 14: R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014; 15: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protocols 2009; 4: 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W (eds) Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. Springer:, New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol 2014; 15: R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Lim E, Vaillant F, Asselin-Labat ML, Visvader JE, Smyth GK. ROAST: rotation gene set tests for complex microarray experiments. Bioinformatics 2010; 26: 2176–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh BN, Lee SC, El-Saafin F, Vanyai HK, Hu Y, Pang SH et al. MOZ regulates B-cell progenitors and, consequently, Moz haploinsufficiency dramatically retards MYC-induced lymphoma development. Blood 2015; 125: 1910–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.