Abstract

The deactivation mechanism after ultraviolet irradiation of 2-thiouracil has been investigated using nonadiabatic dynamics simulations at the MS-CASPT2 level of theory. It is found that after excitation the S2 quickly relaxes to S1, and from there intersystem crossing takes place to both T2 and T1 with a time constant of 400 fs and a triplet yield above 80%, in very good agreement with recent femtosecond experiments in solution. Both indirect S1 → T2 → T1 and direct S1 → T1 pathways contribute to intersystem crossing, with the former being predominant. The results contribute to the understanding of how some noncanonical nucleobases respond to harmful ultraviolet light, which could be relevant for prospective photochemotherapeutic applications.

Noncanonical nucleobases, i.e., DNA or RNA nucleobases with chemical modifications, are gaining increased attention as researchers are realizing that these modifications provide additional possibilities to encode genetic information.1 One important chemical alteration is thionation, where the oxygen atom of a carbonyl group is substituted by a sulfur atom, yielding a thiobase. Such thiobases have been isolated from transfer-RNAs2−4 from all domains of life,5 but they are also commonly found in artificial DNA and RNA systems. They prevent mispairing in DNA-based nanotechnology;6,7 are employed as fluorescent markers;8−10 and—given their excellent binding affinity to biological targets—are also used clinically as cytotoxic agents,11,12 as anti-inflammatory drugs,13 or as antithyroid drugs.14,15 Particularly due to their medicinal relevance in photochemotherapeutic applications,16−21 unravelling the photophysical and photochemical properties of thiobases is decisive. The ability to produce high triplet yields is pivotal to generate singlet oxygen and other reactive species responsible for the cytotoxicity. This ability seems to be linked to the heavy-atom effect of the sulfur atom, because canonical nucleobases exhibit ultrafast (i.e., few picosecond) internal conversion back to the electronic ground state,22,23 while thiobases do not.24 Understanding the photochemistry of noncanonical nucleobases in general is also important in the context of molecular evolution in prebiotic settings, where only the most photostable molecules survived the harsh ultraviolet irradiation on the early earth.22,25,26

A number of recent studies focused on the excited-state dynamics of thiouracils, but a consensus regarding the mechanism to populate triplet states has not been reached. Time-resolved experimental studies show ultrafast near-unity triplet yield for 2-thiouracil (2TU), 2-thiothymine, 2-thiouridine, and 2,4-dithiouracil.21,27−31 Stationary quantum-chemical calculations are available only for 2TU, but different relaxation pathways are proposed to explain intersystem crossing (ISC).32−34 After populating the lowest bright state S2, all studies agree that internal conversion to the S1 should take place. As a subsequent deactivation pathway, two routes for ISC have been proposed: one direct S1 → T1 and involving mostly planar geometries32,33 and one indirect S1 → T2 → T1 with geometries showing a large degree of pyramidalization.34 Because stationary calculations cannot predict the relative importance of these routes and might even overlook additional pathways, a time-dependent study is mandatory.

Here, we investigate the dynamics of the excited states of 2TU (Figure 1), with the aim of providing a clear-cut deactivation mechanism that can also help to enlighten the general photophysics of thiobases and other noncanonical nucleobases, which is a timely topic.21,24,30,35−42 Accurate CASPT2-based surface hopping molecular dynamics simulations including singlet and triplet states have been performed, employing a local development version of the SHARC (Surface Hopping including ARbitrary Couplings) software suite.43−45 Ab initio methods regularly employed for excited-state dynamics simulations, such as CASSCF or TD-DFT, often give a qualitatively inaccurate description of the potential energy landscape.46−50 Hence, here we rely on the MS-CASPT2(12,9)/cc-pVDZ level of theory (multistate complete active space perturbation theory) for all underlying on-the-fly computations of energies, numerical gradients, and relevant couplings between the electronic states. While this is not the first application of MS-CASPT2 in excited-state dynamics simulations (pioneered by the group of Martínez51), here we employ the largest MS-CASPT2 setup to date, to the best of our knowledge. The usage of the MS variant of CASPT2 for dynamics is necessary, because the single-state variant fails to correctly describe excited-state crossings.51,52 Although MS-CASPT2 can create state-oversplitting artifacts,53,54 the good agreement between single-state and multistate CASPT2 static calculations for 2TU34 suggests that these artifacts are not present here. As will be shown below, this computationally expensive approach achieves very good agreement with the available experimental ISC time scales.21,30,42 The orbitals included in the active space (Figure S1) and other details of the calculations as well as a discussion regarding the quality and stability of the computations can be found in the Supporting Information.

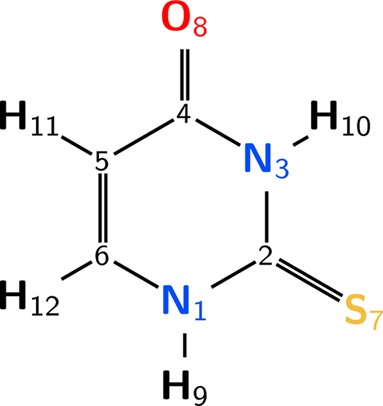

Figure 1.

Structure of 2-thiouracil and atom numbering.

To provide initial conditions for the dynamics simulations, first an absorption spectrum (see Figure S2) was computed from 2000 geometries sampled from the ground-state equilibrium Wigner distribution. The single absorption band obtained shows a maximum at 4.2 eV, almost exclusively due to excitation to the S2 state,34 which is a ππ* excitation from the sulfur atom to one π* antibonding orbital of the pyrimidine ring, denoted as πSπ6* henceforth (see orbital labels in Figure S1). The lower-lying S1 state is of nSπ2 character and does not contribute much to the absorption. Higher-lying excited states were not computed for the absorption spectrum because we are focused on the dynamics after excitation to S2. Accordingly, the dynamics simulations are initiated in the bright S2 state and consider the interaction with all states below, i.e., the S1 and S0 as well as the three lowest triplet states, T1, T2, and T3 (3πSπ2*, 3nSπ2, 3π5π6* at the Franck–Condon geometry). A total of 44 trajectories with a simulation time of 1 ps have been considered; the nuclear dynamics was simulated with a 0.5 fs time step, and the electronic wave function was propagated with a 0.02 fs time step using the “local diabatization” formalism.55,56

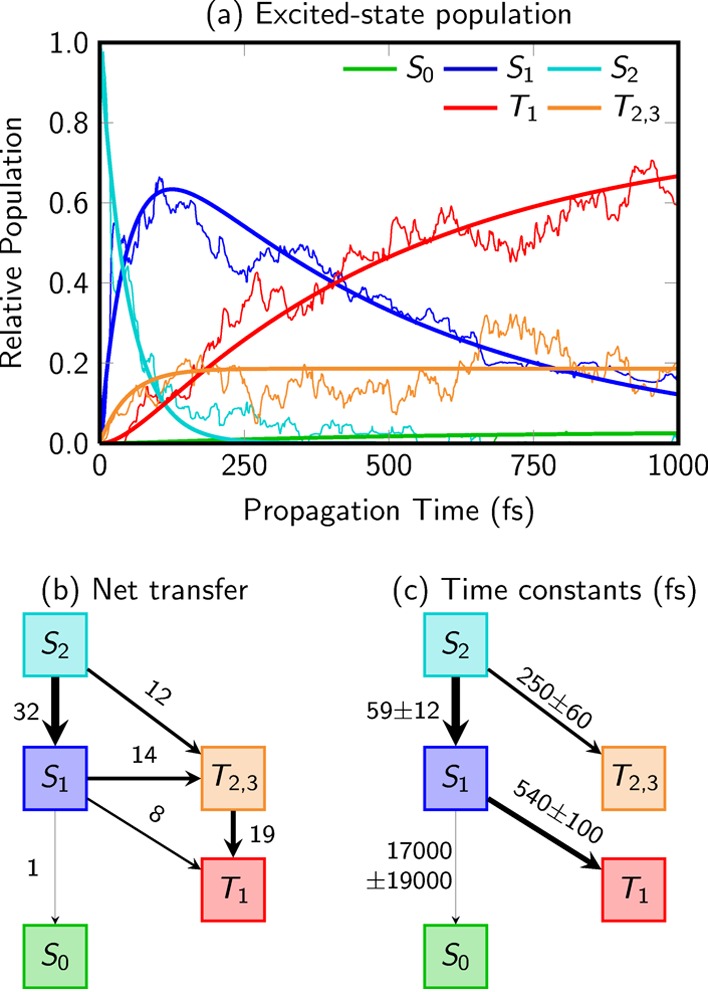

Figure 2a shows the time-evolution of the excited-state populations (thin lines) and the results of a global fit described below (thick lines). For all analysis purposes, the populations of T2 and T3 are merged, because the T3 population is only 2% on average. As can be seen, after excitation to the S2 state, internal conversion to the S1 state is basically completed within 200 fs. Simultaneously, ISC to all three triplet states proceeds on a time scale of a few hundred femtoseconds, whereas hardly any population of the ground state is observed within 1 ps. The triplet population at 1 ps is 80%, while most of the remaining population still resides in S1. This dynamical behavior is different from the canonical nucleobase uracil, where ISC is smaller and ground-state recovery is ultrafast.22,23

Figure 2.

(a) Excited-state populations from 44 trajectories (thin lines) and global fits (thick lines) to the populations. (b) Net population transfer (numbers of trajectories) among the electronic states. (c) Fitted time constants (in femtoseconds) from the global fit. The T3 population was absorbed into the T2 population in all panels. The thickness of the lines in panels b and c relates to the amount of transferred population.

To identify the most relevant deactivation pathways and branching ratios, the net population transfer among the excited states is plotted in Figure 2b. Three different ISC routes are revealed: S2 → T2,3, S1 → T2,3, and S1 → T1. The S1 → T2 route (ignoring the T3 population henceforth), proposed in ref (34), accounts for about 40% of the ISC events and is thus the main ISC pathway. However, routes S1 → T1 and S2 → T2, suggested in earlier works,32,33 account for 35% and 25% of ISC, respectively.

Time scales associated with the excited-state populations in Figure 2a could in principle be derived from a global fit to a kinetic model based on the transition graph in Figure 2b. However, the graph is relatively complex because it contains parallel pathways. In terms of chemical reaction network theory,57 the stochiometry matrix corresponding to the transfer graph exhibits a two-dimensional nullspace. Intuitively, this means that several different combinations of rate constants can lead to the same overall population dynamics. Stated differently, for the given transition graph, the populations do not contain enough information to uniquely estimate all individual rate constants. Therefore, attempting to extract the individual transition rates for the three ISC routes by fitting will not be successful because the different ISC rate constants would be strongly correlated and large fitting errors and essentially arbitrary ISC rates would be obtained.

Instead, for the purpose of obtaining time scales, a simplified kinetic model was devised, where the S1 → T2 → T1 pathway is merged into the competing S1 → T1 pathway. A global fit based on this model (see the Supporting Information for more details) yields the time constants presented in Figure 2c and the corresponding fitted functions shown as thick lines in Figure 2a, which closely follow the actual populations. The error estimates given in Figure 2c were obtained with the bootstrapping method.58 They describe mainly the uncertainty in the populations due to incomplete sampling (i.e., due to the small number of trajectories); systematic errors due to the level of theory and the semiclassical nature of the dynamics method are not included. Consequently, the errors serve as a check as to whether the number of trajectories is sufficient. According to the simplified kinetic model, internal conversion from S2 → S1 proceeds with a time constant of 59 fs. The S1 → S0 deactivation is a much slower process that is not well described here because there are too few hops to the ground state. In addition, two ISC time constants were obtained, one of 540 ± 100 fs for S1 → T1 and another of 250 ± 60 fs for S2 → T2. Both values can be combined to obtain an average ISC time constant of about 400 fs, which is in very good agreement with the values of 340–360 fs reported in aqueous and acetonitrile solution using transient absorption spectroscopy,21,30 and also with the 330 fs obtained for 2-thiothymine.28 Our ISC time constant also agrees reasonably well with the value of 775 fs from very recent multiphoton time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy experiments,42 considering that our simulations do not explicitly account for the multiphoton ionization probe. It has been shown that the inclusion of the time-dependent ionization probabilities in the simulations can easily change the time scales by a factor of 2.59 The kinetic model can also be used to extrapolate the populations to times longer than 1 ps. Including the errors associated with the time constants, a total triplet yield of 90 ± 10% has been obtained, in agreement with the experimental value of 75 ± 20%30 and also with the ones of 90 ± 10%28 or 100 ± 5%29 for the related 2-thiothymine.

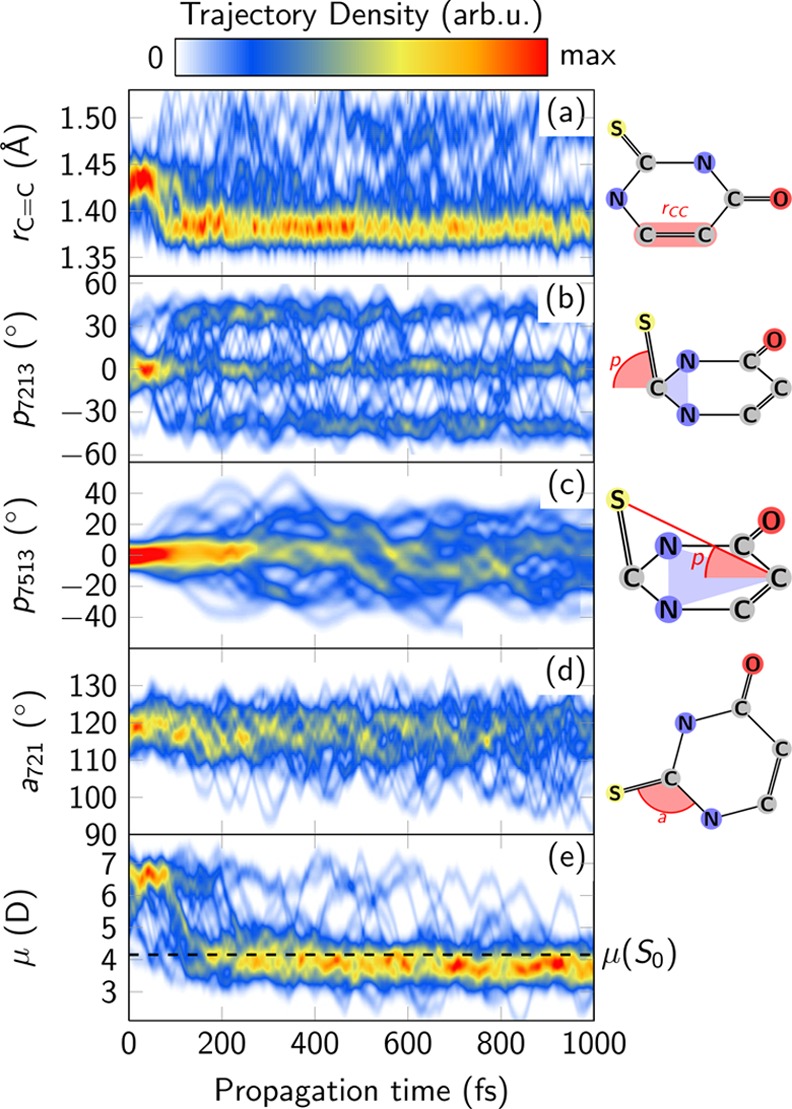

With the aim of identifying important geometrical changes along the excited-state dynamics, the time-evolution of selected internal coordinates is displayed in Figure 3. After excitation in the Franck–Condon region, relaxation to two different S2 minima is possible according to stationary calculations.32−34 These minima differ in structure and the occupation of the antibonding orbitals, either more localized at the C6 atom32−34 or C2 atom34 (recall Figure 1), and therefore are labeled as 1πSπ2* and 1πSπ6 minima, respectively. Which of the minima is actually populated is easily solved by the dynamics simulations. The length of the C5=C6 bond length shown in Figure 3a undoubtedly reveals that most trajectories exhibit a bond length of 1.43 Å during the first 50 fs, which corresponds to the planar 1πSπ6* minimum. In contrast, only two trajectories moved into the pyramidalized minimum (with bond length 1.38 Å) of the 1πSπ2 state, being trapped there for several hundreds of femtoseconds, because there exist sizable barriers to leave this minimum. Accordingly, the S2/S1 (1πSπ2*/1nSπ2) conical intersection presented in ref (34) is not operative. In contrast, because the 1πSπ6* minimum is located very close to another S2/S1 conical intersection involving the (1πSπ6/1nSπ2*) states, it effectively funnels the population toward the S1 state, leading to an S2 lifetime of 59 fs. Subsequently, the bond length distribution shifts to smaller values, and for the rest of the simulation, the trajectories spend most of the time around 1.38 Å, which corresponds to the 1nSπ2 pyramidalized minimum in the S1 state (as well as to other minima, see below).

Figure 3.

Time-dependent evolution of selected internal coordinates in the ensemble of 44 trajectories. The definition of the chosen internal coordinates is schematically depicted on the right (see also Supporting Information). Panel e shows the evolution of the dipole moment of the active state (contour plot) and the ground-state dipole moment μ(S0) (dashed line).

At the operative S2/S1 crossing, both the pyrimidine ring and the thiocarbonyl group are planar, but at the S1 minimum the S atom is displaced out of the ring plane. This strong pyramidalization at the C2 atom is characteristic of the 1nSπ2* minimum and can be quantified by the pyramidalization angles p7213 (defined as the angle between the S7=C2 bond and the C2–N1–N3 plane, see Figure 3b, and related to the planarity of the thiocarbonyl group) and p7513 (which describes how much the S atom is displaced from the molecular plane, see Figure 3c). Both pyramidalization angles are initially distributed around zero, but within 100 fs an equilibrium value of p7213 = ±40° is reached, whereas it takes more than 400 fs for p7513 to stabilize. Inspection of the trajectories (see also Figure S3 in the Supporting Information) confirms that the pyramidalization mechanism involves two stages. First, the system relaxes by puckering the C2 atom out of the ring plane, thereby stabilizing the energy of the 1nSπ2 state by about 0.35 eV. Because only the C2 atom needs to be moved, but not the heavy sulfur atom, puckering takes only tens of femtoseconds after transition to S1 (Figure 3b). In a second stage, the pyramidalizations at the nitrogen atoms N1 and N3 are removed and the planarity of the ring recovered while the pyramidalization at C2 is conserved. Because this second stage necessitates heavy-atom motion, it is far slower, taking several hundred femtoseconds (Figure 3c); this stage leads only to a marginal energetic stabilization (0.03 eV).

After relaxation to the pyramidalized S1 minimum, ISC proceeds efficiently, promoted by small energy gaps between the three states S1, T2, and T1 as well as sizable spin–orbit couplings (up to 150 cm–1).34 On the basis of the trajectories, the “wagging” mode of the S atom has been identified as an important tuning mode that modulates the gap between the 1nSπ2* and 3πSπ2 states. This mode is quantified with the angle α721, sketched in Figure 3d. This angle affects the energy of the 3πSπ2* state more than that of 1nSπ2 and 3nSπ2* (Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). Thus, at angles of about 102° and 128°, the 3πSπ2 state crosses with the 1nSπ2* state, at energies only slightly above the minimum energy of the S1 minimum energy. At these two angles one can also see that the two triplet characters are exchanged, suggesting a nearby T2/T1 conical intersection that favors very efficient internal conversion between both triplet states. These two angles are regularly reached by the trajectories (Figure 3d), providing ample opportunity for ISC and subsequent internal conversion to T1 to take place.

After the transition to T1, the system equilibrates between two distinct local T1 minima, termed “pyramidalized” and “boat” in ref (34). In Figure 3a, most trajectories exhibit values of the C5=C6 bond length of around 1.38 Å, which is typical for the pyramidalized T1 minimum as well as the S1 minimum. A small fraction of the ensemble shows values around 1.49 Å, corresponding to a population of the boat T1 minimum. Pyramidalization angles p7213 (Figure 3b) around ±40° indicate the pyramidalized T1 minimum and values close to zero indicate a population of the boat T1 minimum. Detailed examination of the individual trajectories showed that the average population ratio in the two T1 minima is approximately 2:1, in favor of the pyramidalized minimum.

Internal conversion to the ground state is minimal, in line with experimental evidence of high ISC yields and phosphorescence.30,60 In agreement with this, none of the reported S1/S0 conical intersections32−34 is observed.

Finally, Figure 3e presents the temporal evolution of the permanent dipole moment of the active state. After excitation to S2, its value is about 6.4 D, whereas after relaxation to the lower states it quickly changes to 3.8 D and then does not change notably. This implies that the involved excited states (S1, T1, and T2) have very similar dipole moments, which are also very close to the value of the ground state (4.2 D, see also ref (34)). This fact has important consequences for the photochemical behavior of 2TU in polar solvents, where more polar states tend to be stabilized while unpolar states increase in energy. In the present case, a polar solvent would decrease the energy of S2 (πSπ6*), further enhancing S2 → S1 internal conversion, and would leave the remaining states, and hence the remaining dynamics, mostly unchanged. This could offer an explanation for the good agreement of our simulations and time-resolved experiments in solution,30 even though the simulations neglect solvation effects. This hypothesis is also supported by the very similar absorption maxima reported for different solvents in the literature (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information). In this regard, 2TU seems to be a rare exception from the observation that solvation strongly affects the dynamics of nucleobases.22,23,26 Especially in uracil, the reported ISC yields are strongly solvent-dependent and vary from a few percent in water to about 50% in aprotic, nonpolar solvents.61,62 The SHARC method, using CASSCF potentials, yields for uracil in the gas phase an ISC yield of 67% (extrapolated from the data reported in ref (63)).

In conclusion, nonadiabatic dynamics simulations show that the mechanism of ISC is very efficient in the noncanonical nucleobase 2-thiouracil. The global sketch shown in Figure 4 summarizes the deactivation mechanism. After excitation to the first bright state S2 of 1πSπ* character, the system quickly moves to a mostly planar conical intersection with the S1 (1nSπ*) state and decays with a time constant of 59 fs to S1. Internal conversion from S2 to S1 mainly involves bond length inversion followed by pyramidalization. Almost no ground-state relaxation was observed; instead, extremely efficient ISC from S1 to T2 and T1 occurs, with an average time constant of 400 fs, in agreement with time-resolved experiments in solution.21,30 The most important ISC channel is the indirect S1 → T2 → T1 one, with S1 → T1 and S2 → T2 playing smaller roles. ISC involves strong pyramidalization of the thiocarbonyl group and is promoted by the wagging mode of the same group, which efficiently modulates the gap between 1nSπ* (S1) and 3πSπ* states. Our extrapolated triplet yield is 90 ± 10%, which agrees nicely with the near-unity yields of several experimental studies.28−30

Figure 4.

Summary of the excited-state dynamics of 2-thiouracil, showing excitation (hν), internal conversion in the singlet states (59 fs time constant), and intersystem crossing (400 fs).

These results not only are relevant for 2TU but also evidence how DNA and RNA modifications strongly influence their response to ultraviolet light. For example, thionation can abate the photoprotective abilities inherent to the canonical nucleobases, unless relaxation from the reactive triplet states to the ground state takes place sufficiently fast. However, the ability to populate efficiently triplet states can be exploited to generate singlet oxygen with therapeutic aims, as has been experimentally shown in thiouracils.21,29

Acknowledgments

Funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project P25827, and very generous allocation of computer ressources at the Vienna Scientific Cluster 3 (VSC3) are gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Susanne Ullrich, Marvin Pollum, and Carlos Crespo-Hernández for stimulating discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00616.

Computational and global fitting details, simulated absorption spectrum, and potential energy scans (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Carell T.; Brandmayr C.; Hienzsch A.; Müller M.; Pearson D.; Reiter V.; Thoma I.; Thumbs P.; Wagner M. Structure and Function of Noncanonical Nucleobases. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7110–7131. 10.1002/anie.201201193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon J.; David H.; Studier M. H. Thiobases in Escherchia coli Transfer RNA: 2-Thiocytosine and 5-Methylaminomethyl-2-thiouracil. Science 1968, 161, 1146–1147. 10.1126/science.161.3846.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajitkumar P.; Cherayil J. D. Thionucleosides in Transfer Ribonucleic Acid: Diversity, Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Microbiol. Rev. 1988, 52, 103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Blain J. C.; Zielinska D.; Gryaznov S. M.; Szostak J. W. Fast and Accurate Nonenzymatic Copying of an RNA-like Synthetic Genetic Polymer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 17732–17737. 10.1073/pnas.1312329110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y.; Helm M. RNA Nucleotide Methylation. WIREs RNA 2011, 2, 611–631. 10.1002/wrna.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski F.; Leumann C. J. Alternative DNA Base-Pairs: from Efforts to Expand the Genetic Code to Potential Material Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5669–5679. 10.1039/c1cs15027h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sintim H. O.; Kool E. T. Enhanced Base Pairing and Replication Efficiency of Thiothymidines, Expanded-size Variants of Thymidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 396–397. 10.1021/ja0562447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre A.; Saintomé C.; Fourrey J.-L.; Clivio P.; Laugâa P. Thionucleobases as Intrinsic Photoaffinity Probes of Nucleic Acid Structure and Nucleic Acid-Protein Interactions. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 1998, 42, 109–124. 10.1016/S1011-1344(97)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson L. M. Fluorescent Nucleic Acid Base Analogues. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2010, 43, 159–183. 10.1017/S0033583510000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkeldam R. W.; Greco N. J.; Tor Y. Fluorescent Analogs of Biomolecular Building Blocks: Design, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2579–2619. 10.1021/cr900301e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Périgaud C.; Gosselin G.; Imbach J. L. Nucleoside Analogues as Chemotherapeutic Agents: A Review. Nucleosides Nucleotides 1992, 11, 903–945. 10.1080/07328319208021748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordheim L. P.; Durantel D.; Zoulim F.; Dumontet C. Advances in the Development of Nucleoside and Nucleotide Analogues for Cancer and Viral Diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2013, 12, 447–464. 10.1038/nrd4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennard L. The Clinical Pharmacology of 6-Mercaptopurine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1992, 43, 329–339. 10.1007/BF02220605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. W.; Halverstadt I. F.; Miller W. H.; Roblin R. O. Jr. Studies in Chemotherapy. X. Antithyroid Compounds. Synthesis of 5- and 6- Substituted 2-Thiouracils from β-Oxoesters and Thiourea. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1945, 67, 2197–2200. 10.1021/ja01228a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D. S. Antithyroid Drugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 905–917. 10.1056/NEJMra042972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euvrard S.; Kanitakis J.; Claudy A. Skin Cancers after Organ Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1681–1691. 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey A.; Xu Y.-Z.; Karran P. Photoactivation of DNA Thiobases as a Potential Novel Therapeutic Option. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 1142–1146. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00272-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran P.; Attard N. Thiopurines in Current Medical Practice: Molecular Mechanisms and Contributions to Therapy-Related Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 24. 10.1038/nrc2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reelfs O.; Karran P.; Young A. R. 4-Thiothymidine Sensitization of DNA to UVA Offers Potential for a Novel Photochemotherapy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 148–154. 10.1039/C1PP05188A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridgeon S. W.; Heer R.; Taylor G. A.; Newell D. R.; O’Toole K.; Robinson M.; Xu Y.-Z.; Karran P.; Boddy A. V. Thiothymidine Combined with UVA as a Potential Novel Therapy for Bladder Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1869. 10.1038/bjc.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollum M.; Jockusch S.; Crespo-Hernández C. Increase in the Photoreactivity of Uracil Derivatives by Doubling Thionation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 27851–27861. 10.1039/C5CP04822B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Cohen B.; Hare P. M.; Kohler B. Ultrafast Excited-State Dynamics in Nucleic Acids. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1977–2020. 10.1021/cr0206770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton C. T.; de La Harpe K.; Su C.; Law Y. K.; Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Kohler B. DNA Excited-State Dynamics: From Single Bases to the Double Helix. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2009, 60, 217–239. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollum M.; Martínez-Fernández L.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. Photochemistry of Nucleic Acid Bases and Their Thio- and Aza-Analogues in Solution. Top. Curr. Chem. 2015, 355, 245–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewski A.; Domcke W. On the Mechanism of Nonradiative Decay of DNA Bases: Ab Initio and TDDFT Results for the Excited States of 9H-Adenine. Eur. Phys. J. D 2002, 20, 369–374. 10.1140/epjd/e2002-00164-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinermanns K.; Nachtigallová D.; de Vries M. S. Excited State Dynamics of DNA Bases. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2013, 32, 308–342. 10.1080/0144235X.2012.760884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vendrell-Criado V.; Saez J. A.; Lhiaubet-Vallet V.; Cuquerella M. C.; Miranda M. A. Photophysical Properties of 5-Substituted 2-Thiopyrimidines. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013, 12, 1460–1465. 10.1039/c3pp50058f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taras-Goślińska K.; Burdziński G.; Wenska G. Relaxation of the T1 Excited State of 2-Thiothymine, its Riboside and Deoxyriboside-Enhanced Nonradiative Decay Rate Induced by Sugar Substituent. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2014, 275, 89–95. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2013.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi H.; Kobayashi T.; Suzuki T.; Ichimura T. Excited-State Dynamics of 6-Aza-2-thiothymine and 2-Thiothymine: Highly Efficient Intersystem Crossing and Singlet Oxygen Photosensitization. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 8782–8789. 10.1021/jp102067t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollum M.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. Communication: The Dark Singlet State as a Doorway State in the Ultrafast and Efficient Intersystem Crossing Dynamics in 2-Thiothymine and 2-Thiouracil. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 071101. 10.1063/1.4866447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollum M.; Jockusch S.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. 2,4-Dithiothymine as a Potent UVA Chemotherapeutic Agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17930–17933. 10.1021/ja510611j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G.; Fang W.-h. State-Specific Heavy-Atom Effect on Intersystem Crossing Processes in 2-Thiothymine: A Potential Photodynamic Therapy Photosensitizer. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 044315. 10.1063/1.4776261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbo J. P.; Borin A. C. 2-Thiouracil Deactivation Pathways and Triplet States Population. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1040-1041, 195–201. 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mai S.; Marquetand P.; González L. A Static Picture of the Relaxation and Intersystem Crossing Mechanisms of Photoexcited 2-Thiouracil. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 9524–9533. 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsika S. Modified Nucleobases. Top. Curr. Chem. 2015, 355, 209–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson T.; Bányász A.; Lazzarotto E.; Markovitsi D.; Scalmani G.; Frisch M. J.; Barone V.; Improta R. Singlet Excited-State Behavior of Uracil and Thymine in Aqueous Solution: A Combined Experimental and Computational Study of 11 Uracil Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 607–619. 10.1021/ja056181s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengeliczki Z.; Callahan M. P.; Svadlenak N.; Pongor C. I.; Sztaray B.; Meerts L.; Nachtigallova D.; Hobza P.; Barbatti M.; Lischka H.; et al. Effect of Substituents on the Excited-State Dynamics of the Modified DNA Bases 2,4-Diaminopyrimidine and 2,6-Diaminopurine. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 5375–5388. 10.1039/b917852j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Andrés L.; Merchán M. Are the Five Natural DNA/RNA Base Monomers a Good Choice from Natural Selection? A Photochemical Perspective. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2009, 10, 21–32. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2008.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández L.; González L.; Corral I. An Ab Initio Mechanism for Efficient Population of Triplet States in Cytotoxic Sulfur Substituted DNA Bases: The Case of 6-Thioguanine. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2134–2136. 10.1039/c2cc15775f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández L.; Corral I.; Granucci G.; Persico M. Competing Ultrafast Intersystem Crossing and Internal Conversion: a Time Resolved Picture for the Deactivation of 6-Thioguanine. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1336–1347. 10.1039/c3sc52856a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G.; Thiel W. Intersystem Crossing Enables 4-Thiothymidine to Act as a Photosensitizer in Photodynamic Therapy: An Ab Initio QM/MM Study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2682–2687. 10.1021/jz501159j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.; Sánchez-Rodríguez J. A.; Pollum M.; Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Mai S.; Marquetand P.; González L.; Ullrich S.. Internal Conversion and Intersystem Crossing Pathways in UV Excited, Isolated Uracils and Their Implications in Prebiotic Chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, in press. DOI: 10.1039/C6CP01790H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M.; Marquetand P.; González-Vázquez J.; Sola I.; González L. SHARC: ab Initio Molecular Dynamics with Surface Hopping in the Adiabatic Representation Including Arbitrary Couplings. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 1253–1258. 10.1021/ct1007394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai S.; Marquetand P.; González L. A General Method to Describe Intersystem Crossing Dynamics in Trajectory Surface Hopping. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2015, 115, 1215. 10.1002/qua.24891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mai S.; Richter M.; Ruckenbauer M.; Oppel M.; Marquetand P.; González L.. SHARC: Surface Hopping Including Arbitrary Couplings-Program Package for Non-Adiabatic Dynamics, 2014; sharc-md.org.

- Serrano-Andrés L.; Merchán M. Quantum Chemistry of the Excited State: 2005 Overview. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 2005, 729, 99–108. 10.1016/j.theochem.2005.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S.; Taketsugu T. Nonradiative Deactivation Mechanisms of Uracil, Thymine, and 5-Fluorouracil: A Comparative ab Initio Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 491–503. 10.1021/jp206546g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama A.; Harabuchi Y.; Yamazaki S.; Taketsugu T. Photophysics of Cytosine Tautomers: New Insights into the Nonradiative Decay Mechanisms from MS-CASPT2 Potential Energy Calculations and Excited-State Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 12322–12339. 10.1039/c3cp51617b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbatti M.; Borin A. C.; Ullrich S. Photoinduced Processes in Nucleic Acids. Top. Curr. Chem. 2015, 355, 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai S.; Richter M.; Marquetand P.; González L. Excitation of Nucleobases from a Computational Perspective II: Dynamics. Top. Curr. Chem. 2015, 355, 99–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H.; Levine B. G.; Martínez T. J. Ab Initio Multiple Spawning Dynamics Using Multi-State Second-Order Perturbation Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 13656–13662. 10.1021/jp9063565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley J.; Malmqvist P. Å; Roos B. O.; Serrano-Andrés L. The Multi-State CASPT2 Method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 288, 299. 10.1016/S0009-2614(98)00252-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gozem S.; Huntress M.; Schapiro I.; Lindh R.; Granovsky A. A.; Angeli C.; Olivucci M. Dynamic Electron Correlation Effects on the Ground State Potential Energy Surface of a Retinal Chromophore Model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 4069–4080. 10.1021/ct3003139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granovsky A. A. Extended Multi-Configuration Quasi-Degenerate Perturbation Theory: The New Approach to Multi-State Multi-Reference Perturbation Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 214113. 10.1063/1.3596699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granucci G.; Persico M.; Toniolo A. Direct Semiclassical Simulation of Photochemical Processes with Semiempirical Wave Functions. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 114, 10608–10615. 10.1063/1.1376633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plasser F.; Granucci G.; Pittner J.; Barbatti M.; Persico M.; Lischka H. Surface Hopping Dynamics using a Locally Diabatic Formalism: Charge Transfer in the Ethylene Dimer Cation and Excited State Dynamics in the 2-Pyridone Dimer. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 22A514. 10.1063/1.4738960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M. In Chemical Reactor Theory: A Review; Amundson N., Lapidus L., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1977; pp 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nangia S.; Jasper A. W.; Miller T. F.; Truhlar D. G. Army Ants Algorithm for Rare Event Sampling of Delocalized Nonadiabatic Transitions by Trajectory Surface Hopping and the Estimation of Sampling Errors by the Bootstrap Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 3586–3597. 10.1063/1.1641019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H.; Allison T. K.; Wright T. W.; Stooke A. M.; Khurmi C.; van Tilborg J.; Liu Y.; Falcone R. W.; Belkacem A.; Martínez T. J. Ultrafast Internal Conversion in Ethylene. I. The Excited State Lifetime. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 244306. 10.1063/1.3604007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taherian M.-R.; Maki A. Optically Detected Magnetic Resonance Study of the Phosphorescent States of Thiouracils. Chem. Phys. 1981, 55, 85–96. 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85087-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hare P. M.; Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Kohler B. Solvent-Dependent Photophysics of 1-Cyclohexyluracil: Ultrafast Branching in the Initial Bright State Leads Nonradiatively to the Electronic Ground State and a Long-Lived 1nπ* State. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 18641–18650. 10.1021/jp064714t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brister M. M.; Crespo-Hernández C. E. Direct Observation of Triplet-State Population Dynamics in the RNA Uracil Derivative 1-Cyclohexyluracil. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4404–4409. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M.; Mai S.; Marquetand P.; González L. Ultrafast Intersystem Crossing Dynamics in Uracil Unravelled by Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 24423. 10.1039/C4CP04158E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.