Abstract

Cocrystals of a weakly basic drug (nevirapine) with acidic coformers are shown to alter the solubility dependence on pH, and to exhibit a pHmax above which a less soluble cocrystal becomes more soluble than the drug. The cocrystal solubility advantage can be dialed up or down by solution pH.

Cocrystals can increase drug solubilities by orders of magnitude, yet such enhancement can be thwarted by the extent of ionization1–3 and solubilization4–7 of cocrystal components. For this reason cocrystal solubility only makes sense in light of solution conditions, such as pH (ionization) and additives (solubilizing agents). The present work shows (1) how solubility and thermodynamic stability of cocrystals can change with solution pH, and (2) best and rapid approaches to characterize such behavior. NVP is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)8 used in the treatment of HIV-1 infections.

NVP is a lipophilic molecule that exhibits poor oral bioavailabilty due to dissolution rate limited absorption.9 Formation of NVP cocrystals as a means to enhance aqueous solubilities relative to the pure crystalline drug was recently investigated by Caira et al. 10 Several NVP cocrystals with acidic coformers, maleic acid (MLE), saccharin (SAC) and salicylic acid (SLC), among others, were discovered. The authors of this fine publication observed that dissolution studies failed to reveal the expected increases in cocrystal solubility, based on high coformer to drug solubilities; a trend that our group has confirmed for other cocrystals.11 This motivated us to investigate the reasons for such unexpected findings, and gain a deeper understanding of how these cocrystals work. Chemical structures and pKa values of drug and coformers in the cocrystals we studied are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical structures and pKa values of drug and coformers.

The influence of pH on cocrystal solubility has not generally been recognized and very few articles report the pH associated with cocrystal dissolution and solubility measurements1, 3, 6, 7,12. Cocrystals of a basic drug and an acidic coformer will encounter solution conditions under which the drug and/or coformer may be ionized. Since cocrystal solubility is primarily influenced by the sum of all the cocrystal constituent species in solution (ionized and nonionized, in this case), pH is expected to be a crucial factor in determining such cocrystal solubilities.

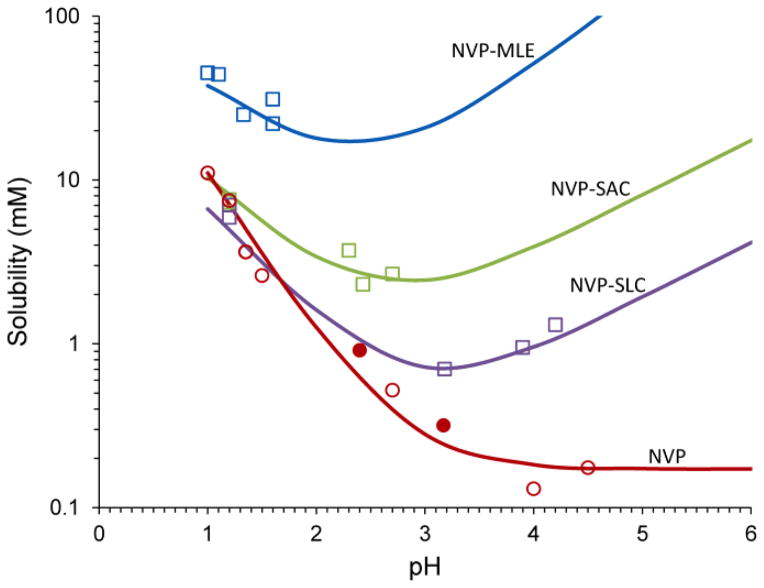

Fig. 1 shows the solubility of NVP and its cocrystals as a function of pH. These results demonstrate that cocrystals change the solubility vs pH curve from an exponential decrease leading to a constant low value for NVP, to a “U shaped” curve with exponentially decreasing and increasing solubilities for its cocrystals. NVP is highly soluble at pH < 3, but its solubility decreases by about 2 orders of magnitude (pH 1 to 4) to a constant low solubility value of approximately 0.2mM at pH > 4. Cocrystals on the other hand, show a solubility decrease (pH 1 to 3) and a solubility increase at pH>3. Some cocrystals also exhibit a transition point or pHmax at the intersection of the drug and cocrystal solubility curves. This means that cocrystals will exhibit higher solubilities than drug at pH > pHmax.

Fig. 1.

Solubility of the basic drug NVP and its cocrystals with acidic coformers: (1:1) cocrystal NVP-MLE, and (2:1) NVP-SAC and NVP-SLC as a function of pH. Symbols represent solubilities determined from solutions saturated with NVP and/or cocrystal at 25°C. pH values correspond to equilibrium pH. The pH value at the intersection of the drug and cocrystal (NVP-SAC and NVP-SLC) solubility curves corresponds to pHmax or transition point above which a less soluble cocrystal becomes more soluble than drug. Curves were calculated from cocrystal and drug solubility-pH dependence according to equations 1 and 2 and parameter values presented in the text and in table 2. Symbols represent: NVP solubility (NVP hydrate-open circles, NVP anhydrous-filled circles) and cocrystal solubilities from eutectic points (squares).

Solubility-pH relationships are well recognized for acids and bases, and their corresponding salts16–18. NVP is a weak base and its solubility as a function of pH is described by

| (1) |

where Sdrug,0 represents the solubility of NVP under nonionizing conditions, 0.172mM at 25°C. Ka represents the ionization constant of NVP conjugate acid. This equation shows that the simultaneous measurement of solubility and pH allows for calculation of solubility at other pH values.

Cocrystal solubility is the sum of all the cocrystal component species in solution that are in equilibrium with the cocrystal. Theoretical solubility-pH relationships for NVP cocrystals can therefore be derived, by considering the two relevant equilibria from which the concentration of cocrystal component species can be obtained. The first is the cocrystal dissolution/dissociation equilibrium defined by a solubility product, Ksp, and the second involves the ionization of drug and coformer characterized by their respective ionization constants, Ka. Derivation of cocrystal solubility equations is presented in the ESI†. The solubility expression is then obtained by considering the mass balance of each cocrystal component (ionized and unionized species) to give

| (2) |

for the 1:1 cocrystals with diprotic acidic coformers. Subscripts D and CF represent drug and coformer. For 2:1 cocrystals with monoprotic acidic coformers, the solubility equation becomes

| (3) |

Cocrystal solubility in the above equations is expressed in terms of moles of drug, unless otherwise indicated.

Excellent agreement between measured and predicted cocrystal solubilities in Fig. 1, demonstrates that these equations predict how pH might influence cocrystal solubility from knowledge of cocrystal Ksp, and Ka values of its components. Cocrystal Ksp values in this work were determined from cocrystal solubility measurements under equilibrium conditions at the cocrystal/NVP hydrate eutectic points unless otherwise indicated.

Caira et al.10 characterized cocrystal solubilities from cocrystal dissolution in water. Our solubility studies suggest that the unexpectedly moderate cocrystal solubility increases (Scc/Sdrug) reported by Caira et al.10 (Table 2) are due to the sensitivity of cocrystal solubility on pH, and to possible transformation of cocrystals to NVP. As shown in Fig. 1, NVP cocrystal solubilities can: (1) vary by orders of magnitude with pH, and (2) approach drug solubility as pH approaches pHmax.

Table 2.

Nevirapine cocrystals: Ksp, pHmax, and Scc/Sdrug.

| Cocrystal | Kspa (M2 or M3) b | pHmaxc | Scc/Sdrug d pH 1 to 5 | Scc/Sdruge pH ? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVP-MLE (1:1) | 1.96 × 10–5 | none | 3.4–906 | 5.3 |

| NVP-SAC (2:1) | 1.05 × 10–10 | 1.1 | 0.9–47 | 1.4 |

| NVP-SLC (2:1) | 3.63 × 10–11 | 1.7 | 0.6–11 | 1.1 |

Calculated from equilibrium solubility measured at cocrystal/drug eutectic points at 25° C described in ESI†.

Units of M2 for 1:1 and M3 for 2:1 cocrystals.

Obtained from the intercept of drug and cocrystal solubility curves in Fig. 1.

Obtained from equilibrium solubility calculation, S vs pH curves in Fig. 1.

From Caira et al., 10 obtained from cocrystal dissolution in water, pH unknown, and NVP solubility in water (0.36mM) at 37° C. The influence of temperature on Scc/Sdrug is expected to be small compared to the influence of pH. Sdrug hydrate increases by about 2 fold between 25 and 37°C19 and the change in Scc/Sdrug may be even smaller if at all.

The Scc/Sdrug reported by Caira et al.10 is highest for the NVP-MLE with a value around 5. We found that this cocrystal is the most soluble of the three cocrystals we studied and does not have a pHmax. In addition, Scc/Sdrug is hugely dependent on pH with a value of 3 at pH 1, 20 at pH 2, and 900 at pH 5. Having the most soluble coformer at the highest molar ratio (1:1) appears to contribute to the high solubility of this cocrystal.

The Scc/Sdrug values for NVP-SAC and NVP-SLC cocrystals were lower than for NVP-MLE, consistent with our findings. Furthermore, the reported10 Scc/Sdrug values were around 1, suggesting the proximity of solution pH to pHmax. We discovered that these cocrystals have pHmax values of 1.1 and 1.7 where Scc/Sdrug = 1. Without knowledge of the pH or pHmax, the increase in solubility that these cocrystals impart could be missed. We observed that dissolution of these three cocrystals lowered solution pH as the acidic coformer concentrations increased (as shown by the decrease in initial pH as solutions reached equilibrium). For these reasons it is essential to measure the pH associated with cocrystal solubility or dissolution studies.

It is important to note that Scc values determined by kinetic methods are generally lower than those measured by equilibrium methods used in our work, as a result of the cocrystal conversion to the constituent drug during dissolution. Scc/Sdrug values determined from eutectic point measurements are equilibrium values and provide a supersaturation index. This means that the huge increase in Scc/Sdrug with pH translates to very high supersaturation with respect to the less soluble drug, leading to more favorable and faster conversions to drug. While the higher Scc/Sdrug values may not be experimentally reached they give insight as to the conversion rates that a cocrystal might experience and inform dissolution and cocrystal formulation approaches.

We have previously demonstrated the importance of the eutectic constant, Keu, as a key indicator of cocrystal to drug solubility, and as an experimentally accessible equilibrium state regardless of the cocrystal solubility relative to pure components.2, 20 Keu is defined as

| (4) |

at the eutectic point where drug and cocrystal are in equilibrium with solution. The terms in brackets represent concentrations. Subscripts eu and total are analytical concentrations (ionized+nonionzed) at the eutectic point.

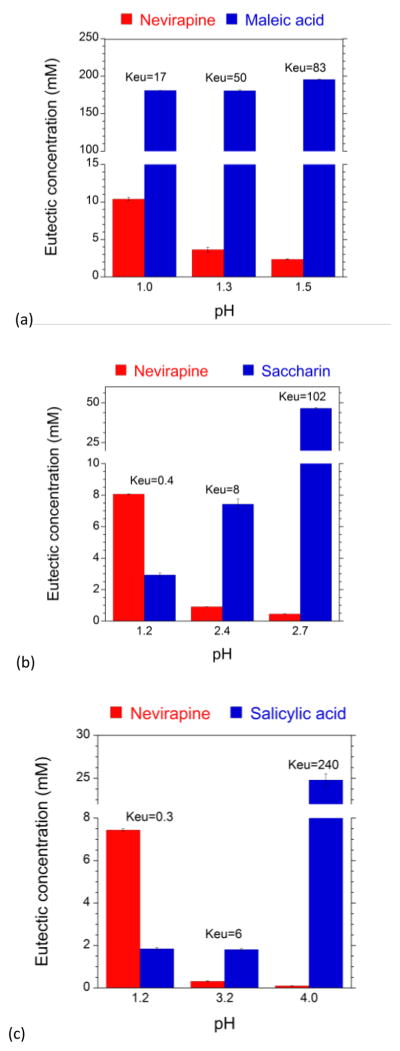

Keu values above cocrystal stoichiometric ratio, indicate that the cocrystal is more soluble than the drug, and the opposite for cocrystals that are less soluble than drug. For the purpose of initially evaluating the NVP cocrystal to drug solubilty and stability, we determined Keu values from measured eutectic concentrations of coformer and drug as shown in Fig. 2. Studies were done at 25°C and pH values between 1 and 4 (Fig. 2). Higher pH values could not be reached due to buffering by the acidic coformers.

Fig. 2.

Eutectic concentrations of drug and coformer at different pH values are key indicators of cocrystal thermodynamic stability relative to drug. a) NVP-MLE (1:1), b) NVP-SAC (2:1), and c) NVP-SLC (2:1). NVP-MLE cocrystal is more soluble than NVP as suggested by Keu > 1, [coformer]eu > [drug]eu. SAC and SLC cocrystals have a reversal in this trend as pH increases, Keu < or > 0.5, indicating a transition point at pHmax. pH values represent equilibrium values and are generally lower than initial pH.

For the 1:1 NVP-MLE cocrystal, Keu > 1 at all pH values studied indicating that the cocrystal is more soluble than the drug since Scc/Sdrug > 1. This cocrystal does not have a pHmax where Keu = 1.

For 2:1 cocrystals a pHmax occurs at Keu = 0.5. Both NVP-SAC and NVP-SLC cocrystals show Keu < 0.5 at pH 1.2 while Keu is > 0.5 for NVP-SAC at pH values ≥ 2.4, and for NVP-SLC at pH values ≥3.2, demonstrating that there is a pHmax for both cocrystals. These results are in excellent agreement with those predicted from the solubility curves in Fig. 1. Small deviations in pHmax for the NVP-SAC cocrystal where Keu = 0.4 suggests a pHmax slightly higher than 1.1, estimated from Fig. 1. This small difference in pHmax values is a consequence of the variability between predicted (Eq.1) and experimentally determined NVP solubility as a function of pH (shown in ESI†).

We have previously demonstrated that Scc/Sdrug can be estimated from Keu according to2, 20:

| (5) |

| (6) |

Scc and Sdrug were experimentally determined from measured eutectic concentrations (Fig. 2) for each cocrystal and respective pH, as described in ESI†. The experimental and predicted Keu dependence on Scc/Sdrug is presented in Fig. 3. The results show excellent agreement between observed and predicted behavior according to equations 5 and 6 for 1:1 and 2:1 cocrystals, respectively.

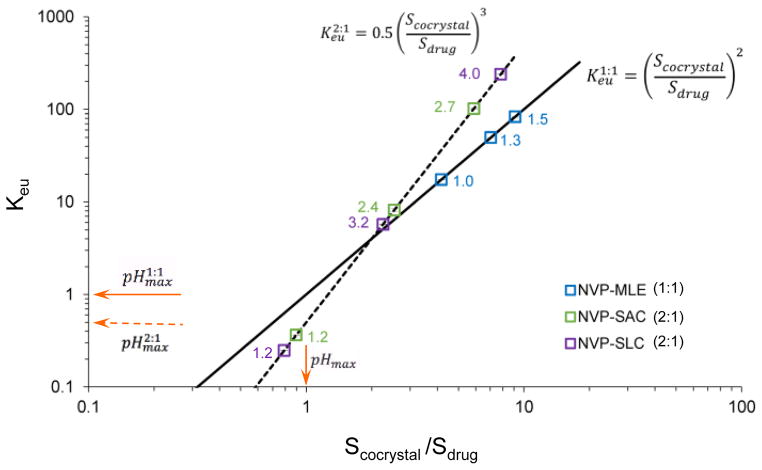

Fig. 3.

Predicted and experimental values of Keu and cocrystal solubility advantage (Scc/Sdrug) for 1:1 NVP-MLE and 2:1 NVP-SAC and NVP-SLC cocrystals. Keu is a key indicator of Scc/Sdrug. Keu dependence on pH reveals the cocrystal pHmax as well as the cocrystal increase in solubility over drug as pH increases. At pHmax, Keu = 1 for 1:1 cocrystals and Keu = 0.5 for 2:1 cocrystals. Log axes are used due to the large range of values. Symbols represent experimental values. Numbers next to data points indicate pH at eutectic point or equilibrium pH. Lines were generated according to equations 5 and 6. Solid lines represent 1:1 cocrystals and dashed lines 2:1 cocrystals.

In conclusion, cocrystal solubility and its advantage over drug can be dialed up or down by solution pH. Cocrystal and drug solubilities without measurement of the corresponding pH will fail to provide meaningful insight about how cocrystals dissolve, and in some cases miss their ability to enhance and modulate solubility. We have also demonstrated that eutectic constants are key indicators of cocrystal stability and solubility. Their measurement requires small amount of materials and time for a solution to reach equilibrium with. Keu also provides a supersaturation index, which is the driving force for cocrystal transformation to the less soluble drug. A subsequent publication will address the influence of the supersaturation index on cocrystal dissolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge partial support from CAPES-Brazil/PVE-Program. GK also acknowledges CAPES-Brazil/PDSE scholarship (process 7537/13-1). NRH and GK are grateful for partial support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R01GM107146. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details and solubility data. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Bethune SJ, Huang N, Jayasankar A, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. Cryst Growth Des. 2009;9:3976–3988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alhalaweh A, Roy L, Rodríguez-Hornedo N, Velaga SP. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:2605–2612. doi: 10.1021/mp300189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy LS, Bethune SJ, Kampf JW, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. Cryst Growth Des. 2009;9:378–385. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang N, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. Cryst Growth Des. 2010;10:2050–2053. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang N, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:5219–5234. doi: 10.1002/jps.22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipert MP, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:3535–3546. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipert MP, Roy L, Childs SL, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104:4153–4163. doi: 10.1002/jps.24640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grob PM, Wu JC, Cohen KA, Ingraham RH, Shih CK, Hargrave KD, Mctague TL, Merluzzi VJ. Aids Res Hum Retrov. 1992;8:145–152. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkar M, Perumal OP, Panchagnula R. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:619–630. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.45401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caira MR, Bourne SA, Samsodien H, Engel E, Liebenberg W, Stieger N, Aucamp M. Crystengcomm. 2012;14:2541–2551. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Good DJ, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. Cryst Growth Des. 2009;9:2252–2264. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keramatnia F, Shayanfar A, Jouyban A. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104:2559–2565. doi: 10.1002/jps.24525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neil MJ, Smith A, Heckelman PE, editors. The Merck index: an encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals. 13th. Merck; Whitehouse Station, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson RMC. Data for biochemical research. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell RP, Higginson WCE. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series a-Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 1949;197:141–159. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avdeef A. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2007;59:568–590. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serajuddin AT. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2007;59:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stahl PH, Wermuth CG International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Handbook of pharmaceutical salts : properties, selection, and use. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira BG, Fonte-Boa FD, Resende JALC, Pinheiro CB, Fernandes NG, Yoshida MI, Vianna-Soares CD. Cryst Growth Des. 2007;7:2016–2023. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Good DJ, Rodríguez-Hornedo N. Cryst Growth Des. 2010;10:1028–1032. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.