Abstract

Introduction

Healthcare databases are useful sources to investigate the epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), to assess longitudinal outcomes in patients with COPD, and to develop disease management strategies. However, in order to constitute a reliable source for research, healthcare databases need to be validated. The aim of this protocol is to perform the first systematic review of studies reporting the validation of codes related to COPD diagnoses in healthcare databases.

Methods and analysis

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library databases will be searched using appropriate search strategies. Studies that evaluated the validity of COPD codes (such as the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision and 10th Revision system; the Real codes system or the International Classification of Primary Care) in healthcare databases will be included. Inclusion criteria will be: (1) the presence of a reference standard case definition for COPD; (2) the presence of at least one test measure (eg, sensitivity, positive predictive values, etc); and (3) the use of a healthcare database (including administrative claims databases, electronic healthcare databases or COPD registries) as a data source. Pairs of reviewers will independently abstract data using standardised forms and will assess quality using a checklist based on the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy (STARD) criteria. This systematic review protocol has been produced in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not required. Results of this study will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication. The results from this systematic review will be used for outcome research on COPD and will serve as a guide to identify appropriate case definitions of COPD, and reference standards, for researchers involved in validating healthcare databases.

Trial registration number

CRD42015029204.

Keywords: Administrative database, Chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, sensitivity and specificity, systematic review, Electronic Health Record, COPD algorithm

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Validation of diagnosis codes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using healthcare databases can contribute to health outcome research. The diagnosis codes may include the International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision and 10th Revision (ICD-9; ICD-10) system, the Real code system and the International Classification of Primary Care system.

This review will be the first to systematically identify and evaluate primary studies that validated the accuracy of healthcare databases with ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for COPD.

It is expected that different healthcare databases validate different algorithms to identify COPD resulting in important heterogeneity. Validated algorithms are context specific and may not be generalisable to other settings.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a global health problem.1 2 It is distinguished by continuous airflow restriction, is frequently progressive and is associated with a chronically increased airway and lung inflammatory reaction to gases or particles.3 4 COPD is correlated with significant morbidity and mortality and is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide.5 On the basis of the WHO estimates (2004), 64 million people had moderate to severe COPD, which led to 3 million deaths.6 The burden of COPD is estimated to increase in the near future because of continued exposure to risk factors and ageing of the population.3 4 Smoking is the main cause of COPD, but other factors, especially exposure to occupational or environmental airborne irritants, may also contribute to the development of this group of lung diseases.3 4

Healthcare databases are increasingly being used to examine features of healthcare delivery, including practice patterns, quality of care, safety and efficacy of drugs, and epidemiological studies. Some of the advantages of healthcare databases included the minimisation of recall bias, better generalisability than randomised trials and better cost-effectiveness approach to research compared to primary data collection.7To be reliably used for research, healthcare databases need to be validated concerning the disease of interest.8–12 This means that the content of the databases (eg, a code of a disease) needs to be ascertained using a reference standard (eg, medical chart).13 Alternatively, algorithms can be developed by combining multiple codes—or sets of codes (eg, diagnosis codes plus prescription or spirometry data)—to enhancethe ability to identify events of interest in the database.13–17

Healthcare databases generally encompass administrative claims data and electronic health records (EHR). Administrative claims databases routinely collect data passively for administrative purposes and for health services delivered by healthcare providers and facilities.18 The patient information collected includes demographics (name, address, birthdate, gender and marital status), the dates of healthcare services delivered and charges for the services, diagnostic procedures performed and healthcare service provider information and in some occasions employment, insurance status and occupational limitations.

Administrative claims databases are excellent resources to investigate the epidemiology17 19 20 and the burden of COPD21 22 and to evaluate longitudinal outcomes of a disease.23 24 Results from analysing these databases can assist in developing disease management strategies (including education regarding the disease, optimisation of evidence-based medications, information, case manager support and institution of self-management principles) to improve the health of subjects suffering from COPD.25

EHRs consist of digital files used by healthcare providers for patient care and, unlike administrative claims databases, include clinical notes, medical records, the treatment histories of patients and prescription records, as well as radiology and laboratory data.26 Despite the fact that EHRs are not established for research purposes, similar to most administrative databases, they are frequently used for healthcare delivery and facilitation of decision-making processes as well as research.26 27

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), used in the UK, is one such EHR. It is an excellent resource with which to study COPD, as it is based on a large cohort and contains disease severity indicators and long-term follow-up information from a patient's integrated medical history.28–30

Generally, administrative claims databases use the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes for COPD (491, 492 or 496), or the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes (J43 and J44). EHRs such as the UK CPRD database employ the Read code, which is a hierarchical clinical coding system of medical and prescription terms.28 Some Read codes for COPD are 1001, 9876 and 10863 (see ref. 28 for a list of COPD-related Read codes). The International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) is another coding system which is widely used in primary healthcare and in research.31–33 The codes for COPD in the ICPC system are R79 and R95.

There are several studies that assessed the validity of healthcare databases for COPD,13 17 28 34 however, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic assessment of algorithms or case definitions of COPD have been published in the medical literature. With the present protocol, we aim to systematically evaluate validation studies of diagnostic codes or algorithms to identify cases of COPD.

Research question

The primary research question is the accuracy of algorithms to correctly identify patients with COPD in healthcare databases (administrative claims, EHR or COPD registries). The target populations are patients with COPD, the index test will be healthcare data algorithms for COPD, and the reference standard will be medical charts, validated electronic health records or COPD registries. Our primary outcome is the accuracy (expressed in terms of sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values) of healthcare data algorithms to discriminate cases of COPD.

Methods

Literature search

Comprehensive searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Web of Science and the Cochrane Library, from their inception, will be performed to identify published peer-reviewed articles. We developed a search strategy based on the combination of: (1) keywords and MeSH terms to identify records concerning COPD; and (2) a search strategy based on the combination of terms used by Benchimol et al,18 the Mini-Sentinel program35 36 and a systematic review that evaluated EHR-based primary studies.26 The developed search strategy is available as online supplementary appendix. To retrieve additional articles, relevant reference lists of key articles will be hand searched. The ‘Cited-By’ tools in PubMed and Google Scholar will also be used to find relevant articles that cited the article of interest, identified through the aforementioned search strategy. Titles and abstracts will be screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers and discrepancies will be resolved by discussion.

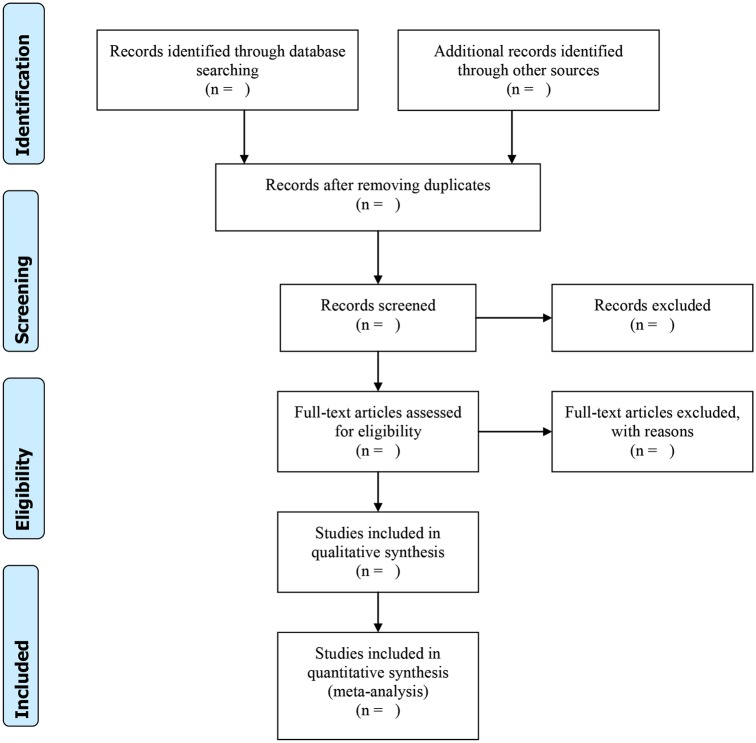

This review protocol has been prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement37 and the results will be presented following the PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1). This protocol has also been published in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews with registration number CRD42015029204 (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO).

Figure 1.

Study screening process (PRISMA flow diagram).

bmjopen-2016-011777supp.pdf (160.5KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

Full texts of eligible peer-reviewed articles, without limits on publication date and published in English, that used healthcare data to validate diagnosis codes for COPD diagnoses will be obtained. For each study, the following inclusion criteria will be applied: (1) the presence of a reference standard case definition for the disease of interest; (2) the presence of at least one test measure (eg, sensitivity, positive predictive values, etc); (3) the use of an administrative claims or EHR database as a data source; and (4) the use of a database from a representative sample of the general population.15 26

At the initial stage, titles and abstracts will be screened for potentially eligible studies. Subsequently, full texts of articles will be obtained and assessed to determine if they meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data abstraction will be conducted using standardised data collection forms, which will first be tested on a sample of eligible articles. Two review authors working independently and in tandem will carry out title, abstract and full-text screening and data abstraction. Any discrepancies will be resolved by consensus andwhere necessary, a third review author will be involved. Calibration exercises will be performed at each level of the process.

Data extraction

Data extraction will include the following information:

The details of the included study (containing the title, the year of publication and the journal, the country of origin and the sources of funding; the first author will be used as the study ID);

The disease of interest (COPD);

The code tested (such as ICD-9, ICD-10, or R79 and R95);

The algorithm(s) tested including COPD code, prescription fills (eg, bronchodilators), use of spirometry, current procedural terminology, timing of diagnosis, etc;

Any information about the performance of the COPD definition/algorithm in subpopulations (eg, age group, sex, smoking status, GOLD grade of airflow limitation,2 socioeconomic status, WHO body mass index category, previous record of asthma diagnosis28)

The target population from which the healthcare data were collected;

The type of healthcare database used (eg, hospitalisation discharge data, electronic health record, etc);

The modality of algorithm development (eg, using Classification and Regression Trees, logistic regression, expert opinion…);

External validation;

The use of training and testing cohorts;

The reference standard used to determine the validity of the diagnostic code (eg, medical chart review, patient self-reports, disease registry, etc);

The characteristic of the test used to determine the validity of the diagnostic code or algorithm (eg, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs), area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, likelihood ratios and κ statistics);

Quality assessment

The design and methods of the included primary studies will be assessed using a checklist developed by Benchimol et al,18 based on the criteria published by the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy (STARD) initiative for the accurate reporting of diagnostic studies.38 This standardised checklist is composed of 40 items to assess the quality of the methods and the reporting of studies that validated codes or algorithms used to identify patients with the disease of interest within a healthcare database (see online supplementary appendix). Two reviewers will be involved in the quality assessment and will work independently and in tandem. Any disagreement will be solved by discussion. The presence of potential biases within the studies will be reported descriptively.

No subgroup analysis or publication bias assessment is anticipated.

Analysis

For each algorithm, the performance statistics, provided in each of the included studies, will be abstracted. Validation statistics may include sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV. Sensitivity measures the degree to which a diagnosis code (eg, ICD-9 491 or Read code 1001) correctly identifies individuals possessing the characteristic of interest (ie, COPD) in the source used as a reference standard (eg, medical chart).39 PPV is the number of true positives divided by the total number of cases receiving the code and expresses the likelihood that the code corresponds to a true-positive case. NPV is the number of true negatives divided by the total number of cases without the code of interest and expresses the likelihood that the absence of the code corresponds to a true-negative case. Where possible, PPVs and NPVs will be calculated if not reported. Ninety-five per cent CIs will be calculated when they are not reported in the articles. Where possible, validation statistics will be aggregated and stratified by healthcare data source (outpatient vs inpatient data), type of EHR code (ICD-9, ICD-10, Read, etc) and country of origin.

Meta-analysis

Where there are studies with homogeneous data, we will use raw data to construct meta-analyses. A bivariate model will be used to derive summary estimates of sensitivity and specificity and their 95% CIs.40 Data will be analysed using a random-effects model so that sensitivity and specificity are assumed to vary across studies. In addition, summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves will be constructed and pooled estimates of LR+, LR− and diagnostic odds ratio will be calculated. Heterogeneity will be assessed by visual inspection of forest plots and ROC plots as well as regression analysis suggested by Reitsma.40 Where there is important heterogeneity, we will not pool the data.

Ethics and dissemination

This review protocol will use publicly available data without directly involving human participants; hence, approval from an ethics committee is not required. An outline of the protocol has been published in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews in 2015, registration number CRD42015029204. The results will summarise the studies that validated diagnostic codes for COPD in healthcare databases. Where possible, a quantitative synthesis of the accuracy data will be provided and the outcomes using different algorithms will be discussed. Findings of the review will be presented at relevant scientific conferences and disseminated through publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Footnotes

Contributors: IA, JMR and MLL conceived the study. JMR, IA, MLL, FC, MO, AC, GD, CC, GA and AM were responsible for designing the protocol. MLL, JMR and IA drafted the protocol manuscript. JMR, IA, FC and MO developed the search strategy. JMR, IA, MLL, FC, MO, AC, GD, CC, GA and AM critically revised the successive versions of the manuscript and approved the final version. IA acts as guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The results from the final review will be published.

References

- 1.GOLD GIfCLO. Pocket guide to COPD diagnosis, management and prevention. 2015. http://www.goldcopd.com

- 2.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:347–65. 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones PW, Nadeau G, Small M et al. Characteristics of a COPD population categorised using the GOLD framework by health status and exacerbations. Respir Med 2014;108:129–35. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–55. 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange P, Marott JL, Vestbo J et al. Prediction of the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, using the new GOLD classification. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:975–81. 10.1164/rccm.201207-1299OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adeloye D, Chua S, Lee C et al. Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2015;5:020415 10.7189/jogh.05-020415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:323–37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraha I, Giovannini G, Serraino D et al. Validity of breast, lung and colorectal cancer diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010409 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraha I, Serraino D, Giovannini G et al. Validity of ICD-9-CM codes for breast, lung, and colorectal cancers in three Italian administrative healthcare databases: a diagnostic accuracy study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010547 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West SL, Ritchey ME, Poole C. Validity of pharmacoepidemiologic drug and diagnosis data. In: Strom BL, Kimmel SE, Hennessy S, eds. Pharmacoepidemiology. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012:757–94. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abraha I, Orso M, Grilli P et al. The current state of validation of administrative healthcare databases in Italy: a systematic review. Int J Stat Med Res 2014;3:309–20. 10.6000/1929-6029.2014.03.03.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraha I, Montedori A, Eusebi P et al. The current state of validation of administrative healthcare databases in Italy: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:400. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacasse Y, Daigle JM, Martin S et al. Validity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnoses in a large administrative database. Can Respir J 2012;19:e5–9. 10.1155/2012/260374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lix LM, De Coster C, Currie R. Defining and validating chronic diseases: an administrative data approach. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chubak J, Pocobelli G, Weiss NS. Tradeoffs between accuracy measures for electronic health care data algorithms. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:343–9.e2. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharifi M, Krishanswami S, McPheeters ML. A systematic review of validated methods to capture acute bronchospasm using administrative or claims data. Vaccine 2013;31(Suppl 10):K12–20. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green ME, Natajaran N, O'Donnell DE et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care: an epidemiologic cohort study from the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network. CMAJ Open 2015;3:E15–22. 10.9778/cmajo.20140040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, To T et al. Development and use of reporting guidelines for assessing the quality of validation studies of health administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:821–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anecchino C, Rossi E, Fanizza C et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pattern of comorbidities in a general population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2007;2:567–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faustini A, Canova C, Cascini S et al. The reliability of hospital and pharmaceutical data to assess prevalent cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 2012;9:184–96. 10.3109/15412555.2011.654014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bustacchini S, Chiatti C, Furneri G et al. The economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderly: results from a systematic review of the literature. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2011;17(Suppl 1):S35–41. 10.1097/01.mcp.0000410746.82840.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simoni-Wastila L, Blanchette CM, Qian J et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Medicare beneficiaries residing in long-term care facilities. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2009;7:262–70. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismaila A, Corriveau D, Vaillancourt J et al. Impact of adherence to treatment with tiotropium and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:1427–36. 10.1185/03007995.2014.908828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abudagga A, Sun SX, Tan H et al. Exacerbations among chronic bronchitis patients treated with maintenance medications from a US managed care population: an administrative claims data analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2013;8:175–85. 10.2147/COPD.S40437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice KL, Dewan N, Bloomfield HE et al. Disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:890–6. 10.1164/rccm.200910-1579OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dean BB, Lam J, Natoli JL et al. Review: use of electronic medical records for health outcomes research: a literature review. Med Care Res Rev 2009;66:611–38. 10.1177/1077558709332440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams F, Boren SA. The role of the electronic medical record (EMR) in care delivery development in developing countries: a systematic review. Inform Prim Care 2008;16:139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quint JK, Mullerova H, DiSantostefano RL et al. Validation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease recording in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD-GOLD). BMJ Open 2014;4:e005540 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothnie KJ, Mullerova H, Hurst JR et al. Validation of the recording of acute exacerbations of COPD in UK primary care electronic healthcare records. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0151357 10.1371/journal.pone.0151357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wurst KE, St Laurent S, Mullerova H et al. Characteristics of patients with COPD newly prescribed a long-acting bronchodilator: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:1021–31. 10.2147/COPD.S58258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soler JK, Okkes I, Oskam S et al. An international comparative family medicine study of the Transition Project data from the Netherlands, Malta and Serbia. Is family medicine an international discipline? Comparing diagnostic odds ratios across populations. Fam Pract 2012;29:299–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soler JK, Okkes I, Wood M et al. The coming of age of ICPC: celebrating the 21st birthday of the International Classification of Primary Care. Fam Pract 2008;25:312–17. 10.1093/fampra/cmn028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minas M, Koukosias N, Zintzaras E et al. Prevalence of chronic diseases and morbidity in primary health care in central Greece: an epidemiological study. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:252 10.1186/1472-6963-10-252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J et al. Identifying individuals with physician diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD 2009;6:388–94. 10.1080/15412550903140865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carnahan RM, Moores KG. Mini-Sentinel's systematic reviews of validated methods for identifying health outcomes using administrative and claims data: methods and lessons learned. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(Suppl 1):82–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McPheeters ML, Sathe NA, Jerome RN et al. Methods for systematic reviews of administrative database studies capturing health outcomes of interest. Vaccine 2013;31(Suppl 10):K2–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD Initiative. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:40–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West SL, Strom BL, Poole C. Validity of pharmacoepidemiologic drug and diagnosis data. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW et al. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:982–90. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011777supp.pdf (160.5KB, pdf)