Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether vector representations encoding latent topic proportions that capture similarities to MeSH terms can improve performance on biomedical document retrieval and classification tasks, compared to using MeSH terms.

Materials and Methods

We developed the TopicalMeSH representation, which exploits the ‘correspondence’ between topics generated using latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and MeSH terms to create new document representations that combine MeSH terms and latent topic vectors. We used 15 systematic drug review corpora to evaluate performance on information retrieval and classification tasks using this TopicalMeSH representation, compared to using standard encodings that rely on either (1) the original MeSH terms, (2) the text, or (3) their combination. For the document retrieval task, we compared the precision and recall achieved by ranking citations using MeSH and TopicalMeSH representations, respectively. For the classification task, we considered three supervised machine learning approaches, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), logistic regression, and decision trees. We used these to classify documents as relevant or irrelevant using (independently) MeSH, TopicalMeSH, Words (i.e., n-grams extracted from citation titles and abstracts, encoded via bag-of-words representation), a combination of MeSH and Words, and a combination of TopicalMeSH and Words. We also used SVM to compare the classification performance of tf-idf weighted MeSH terms, LDA Topics, a combination of Topics and MeSH, and TopicalMeSH to supervised LDA's classification performance.

Results

For the document retrieval task, using the TopicalMeSH representation resulted in higher precision than MeSH in 11 of 15 corpora while achieving the same recall. For the classification task, use of TopicalMeSH features realized a higher F1 score in 14 of 15 corpora when used by SVMs, 12 of 15 corpora using logistic regression, and 12 of 15 corpora using decision trees. TopicalMeSH also had better document classification performance on 12 of 15 corpora when compared to Topics, tf-idf weighted MeSH terms, and a combination of Topics and MeSH using SVMs. Supervised LDA achieved the worst performance in most of the corpora.

Conclusion

The proposed TopicalMeSH representation (which combines MeSH terms with latent topics) consistently improved performance on document retrieval and classification tasks, compared to using alternative standard representations using MeSH terms alone, as well as, several standard alternative approaches.

Keywords: Topic models, MeSH, PubMed, Document retrieval, Document Classification

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

To better manage and search the biomedical literature, the US National Library of Medicine (NLM®) developed the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) controlled vocabulary for indexing MEDLINE® articles. MeSH has been used to improve PubMed query results [1, 2], information retrieval, document clustering, and query refinement in ‘downstream’ applications that use PubMed® abstracts. For instance, [3] has shown that including MeSH can improve the retrieval performance from 2.4% to 13.5% among 10 different information retrieval models. MeSH has also been used in several web tools for searching biomedical literature to cluster documents [4]. Furthermore, visualization tools like LigerCat [5] and MESHy [6] have used MeSH to help users understand and filter PubMed query results.

However, assigning MeSH terms to biomedical articles is a complex, subjective, and time-consuming task. Considerable research has therefore been devoted to developing tools that can automatically index biomedical articles with MeSH terms[7, 8, 9, 10]. In 2000, the NLM developed the Medical Text Indexer (MTI) [9] to assist human annotators with indexing recommendations in the form of MeSH headings and heading/subheading pairs. A relatively small group of indexing contractors and staff at the NLM are responsible for attaching MeSH terms to biomedical articles. This semi-automated indexing process may avoid many issues involved with natural language processing, but also has several limitations:

Human consistency on MeSH indexing ranges from 33.8% to 74.7% depending on the type and category of indexing terms [11].

MeSH terms in each abstract are binary tags. Aside from major/regular MeSH assignments, there are no precise MeSH term weights provided for articles.

Missing MeSH terms: There are 27,455 descriptors in the 2015 version of MeSH. NLM's MeSH specialists continually revise and update the MeSH vocabulary [9]. They define new terms as they appear in the literature or in emerging areas of research within the context of the existing vocabulary and recommend additions to MeSH. There is thus a high chance of missing emerging concepts such as “biomedical informatics” or “big data” in older articles.

Some citations may be missing relevant MeSH terms. According to a recent analysis by the NLM, 25% of the citations are completed within 30 days of receipt, 50% within 60 days, and 75% within 90 days [7] (implying that 25% of citations have not yet been tagged 90 days after publication). Furthermore, NLM does not typically re-index old articles with new MeSH terms [12].

The utility of using combinations of MeSH descriptors to query PubMed has been shown to be a valuable mechanism to identify relevant articles [13, 14], but MeSH terms by themselves do not indicate meaningful clusters or themes in a specific subject area.

In contrast to MeSH terms, topic models [15] are a class of statistical machine learning algorithms that aim to extract the semantic themes (topics) from a corpus of documents. These topics describe the thematic (topical) composition of documents and can thus capture the semantic similarity between them. MeSH terms are manually created and manually maintained by domain experts to cover all generally important themes. In contrast, topics extracted from a subset of documents are specific to that subset. Thus they may find corpus-specific themes that may not generally exist in MeSH. Such themes may uncover a specific set of topics for a particular domain or sub-domain, thus providing a better overview of search results [16].

Although researchers continue to develop better and faster topic model algorithms, there is limited work on assessing their utility in real world applications. This is because topic model developers typically focus on intrinsic quality: that is, how well (probabilistically) the topic model explains (held-out) text. Such intrinsic measures do not necessarily reflect utility in practice [17]. Moreover, most work on topic models treats the task as entirely unsupervised, i.e., these models assume no prior relationship between individual words or tokens in the vocabulary. However, MeSH terms are drawn from a manually curated controlled vocabulary with known structure; it is desirable to exploit this information while simultaneously leveraging the flexible probabilistic framework of topic models.

Recently, Chuang et al [18] developed a method for assessing the correspondence between topics from topic models and those independently developed by domain experts. In this paper, we use a variation of their method to estimate correspondence between topics generated by probabilistic topic models and manually assigned MeSH terms for PubMed citations. We use this to induce the TopicalMeSH representation for PubMed citations, which effectively combines statistical topic modeling approaches with MeSH terms.

2 Related Work

Topic models have broad applicability in biomedical informatics. Recent examples include treatment discovery from clinical cases, [19, 20], predicting behavior codes from couple therapy transcripts [21], risk stratification in ICU patients from nursing notes [22], summarizing themes in large collections of clinical reports [23], and discovering health-related topics in social media [24, 25, 26].

Several studies have examined the application of topic models to PubMed data. Most recently, Zhu et al. [27] used labeled Latent Dirchlet Allocation (labeled LDA) to annotate MeSH terms. Labeled LDA is a supervised topic model for uncovering latent topics that correlate with user tags in labeled corpora. However, labeled LDA did not perform better than the other methods evaluated [28]. Elsewhere, Newman et al. [29] presented a resampled author model that combines both general LDA and the author-topic model (in this case MeSH terms were used as the “authors”). The resampled author model provided an alternative and complementary view of the relationships between MeSH terms. However, their model did not outperform the author-topic model with respect to predicting MeSH terms for biomedical articles.

To the best of our knowledge there have been no previous evaluations of the correspondence between topics from topic models and MeSH terms in PubMed. Nor has there been investigation into whether topics might complement MeSH terms.

Many topic model algorithms have been evaluated with respect to perplexity, a measure of how well a model explains held-out data [30]. However, perplexity does not correspond to utility [17]. MeSH's hierarchical structure has also been explored to identify biomedical topic evolution [31]. More recently, the graph-sparse LDA model was developed to generate more interpretable topics by leveraging relationships expressed by controlled vocabulary structures. In this model, a few concept-words from the controlled vocabulary can be identified to represent generated topics. MeSH was shown to work well in this model to help summarize biomedical articles [32].

In contrast to this previous work, here we investigate correspondence of topic models to MeSH terms and explore whether combing topics and MeSH terms into a joint representation of documents might offer advantages compared to alternative representations, such as the MeSH terms alone or MeSH terms augmented with the text.

3 Methods

Chuang et al. [18] developed an evaluation framework to assess the quality of latent topics generated by a topic model, with respect to a reference set of topics independently developed by domain experts. This framework produces a correspondence matrix of similarity scores between the reference topics and the latent topics. Chuang et al.'s reference topics were derived from manually curated expert topic titles, key phrases, and sets of related documents. These were used to create word distributions for each reference topic using tf-idf weighting and normalization.

In this paper, we propose a variation of Chuang et al.'s method to compute the correspondence between MeSH terms and topics generated by LDA. We constructed our MeSH vectors in a similar way as Chuang et al. constructed their reference topics. We did not need a separate set of experts to create and assign key phrases, because MeSH terms already play that role for PubMed articles. Rather than using this correspondence to evaluate the quality of estimated topics (as per the original idea), here we use correspondence to induce a new representation that captures correlations between MeSH terms and latent topics.

In this section we provide a brief description of LDA; describe the construction of the correspondence matrix between topics and MeSH terms (which allows us to align MeSH terms and topics); present the design of our work flow and evaluation measures; and provide a brief description of the test data we use.

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA)

LDA [33] is a probabilistic model that assumes that each document is generated from a mixture of topics, and that each topic corresponds to a distribution over all words in the corpus. Informally, the ‘generative story’ for LDA is as follows. First, a document is generated by drawing a mixture of topics that the document is about. To generate each word in this document, one draws a topic from this distribution and subsequently selects a word from the distribution over the vocabulary of the whole corpus corresponding to this topic. The LDA algorithm uses this generative model to uncover the latent topics contained within a given a corpus. Specifically, it estimates the parameters that define document topic mixtures and the conditional probabilities of each word given each topic. Parameter estimation is usually done via sampling approaches.

The number of topics produced by LDA must be prespecified. Determining the ‘right’ number of topics for different data sets remains a challenge. When the number of topics increases, redundant and nonsense topics may be generated. But at the same time, these topics' effects in our final TopicalMeSH representation matrix (Figure 2) will be dampened by the correspondence computation and matrix product computation in Figure 2. When the number of topics is small, we may miss some good topics. Our TopicalMeSH matrix will then be affected in this case.

Figure 2.

A schematic of our approach to inducing TopicalMeSH representations of articles.

We conducted experiments with various numbers of topics ranging from 5 to 300. Performance in the information retrieval task was quite consistent. Runs with larger numbers of topics had slightly better performance than those with smaller numbers of topics. Hence here we used the number of unique MeSH terms (a relatively high number for LDA in general) in the test corpus as the number of topics. Although it may seem odd that a topic model of only 5 topics did not dramatically lower performance, recall that each of the 15 corpora were based on a specific query tuned to the medication class of interest. Thus one dominant theme in each corpus is likely to be the targeted medication class. As a result, it is likely that a topic model, even one with only 5 topics, will directly identify this theme, highlighting an advantage of TopicalMeSH.

Correspondence

Each topic generated by LDA is a distribution over all of the unique words in the corpus. To compute the similarity scores between inferred topics and (observed) MeSH terms, we represented each MeSH term as a distribution of the words contained in the documents to which it had been assigned. To create the distribution for a MeSH term, we collected all of the words in documents from the corpus that were tagged with that MeSH term. After removing PubMed's stop words, we used tf-idf (Equation 1) to re-weight the remaining words in the documents tagged with that MeSH term and then normalized the resulting MeSH vector representations to sum to one.

| (1) |

where tfw,d is the term frequency of word w in document d, dfw,D is the document frequency that word w appears in all documents D, and N is the total number of documents.

The dimensionality of our correspondence matrix is T by M, where T is the number of topics in the LDA model and M is the number of unique MeSH Terms. Each entry of this matrix is a similarity score between the word frequency vectors constructed for a given MeSH term and a topic's estimated distribution over words.

There are several ways to compute the similarity between two distributions, including cosine similarity, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient, and the rescaled dot product. Chuang et al. [18] compared several different methods for computing the similarity between two sets of topics generated from two LDA models on the same corpus and found that the rescaled dot product best predicted human judgment of similarity in terms of precision and recall.

This product is computed for two vectors P and Q as follows:

| (2) |

Where P⃗ and Q⃗ are vectors consisting of weights corresponding to all unique words sorted in descending order by weight, and Q⃖ is a vector of weights for all unique words sorted in ascending order by weight. In our case, P is the inferred distribution of words for a topic uncovered by LDA, while Q is the normalized tf-idf vector encoding word frequencies for a particular MeSH term.

The terms used for rescaling, dMax and dMin, estimate the maximum and minimum dot product that could be obtained between vectors with the values of P and Q, by reordering their entries (irrespective of which term they refer to) such that they are both arranged in descending order (dMax), or arranged in the opposite order (dMin) to one another.

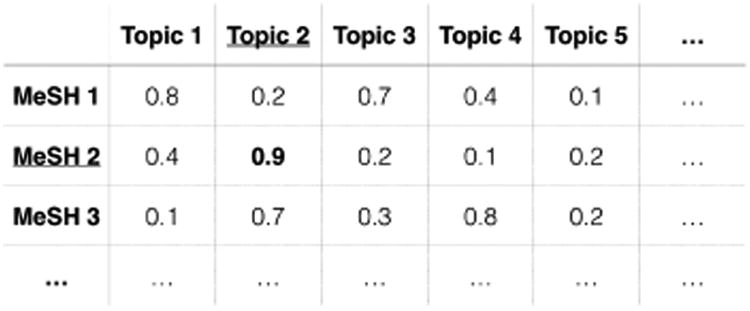

Figure 1 provides an illustrative correspondence matrix. Here, Topic 2 is the corresponding topic for MeSH 2. Note that a single MeSH term may have multiple corresponding topics and a single topic may also be mapped to multiple MeSH terms.

Figure 1.

Correspondence Matrix of MeSH terms and Topics.

Study Workflow

Figure 2 shows the approach we took in this work. Process MeSH generated two matrices: M1 and M2. M1 is the binary Document-to-MeSH matrix, which has a dimensionality of D by M, where D is the total number of documents and M is the number of unique MeSH terms. M2 is the M by W MeSH-to-Word matrix, where W is the number of unique words. To make it consistent with LDA's distribution over words, we removed both PubMed's stop words and low frequency words that only appear in one document. The latter words are of little use in LDA because it is sensitive to word co-occurrence. We used tf-idf to weight the remaining words and then normalized the weights so that they summed to one. Run Topic Model used the LDA-c code (http://www.cs.princeton.edu/blei/lda-c/index.html) to perform topic modeling using variational inference [33]. Since our goal was to compare the utilities of MeSH terms and topic models, we simply used the number of unique MeSH terms (M) indexed in Input Data as the number of topics for LDA.

The symmetric Dirichlet prior parameter, α, was set to 1/T, where T is the number of topics. We set the the convergence criterion for variational expectation maximization (EM) to 0.0001 and the maximum number of iterations of variational EM to 1000. In our experiments, the convergence criterion was met across all corpora within 70 iterations.

Running LDA generated two Matrices: M3 and M4. M3 is the Topic-to-Word matrix with dimensions T by W. Finally, M4 is the D by T Document-to-Topic matrix.

Compute Correspondence Matrix uses the rescaled dot product defined above to calculate the similarity score of each MeSH term and topic pair based on the M2 and M3 matrices. M5 is the Topic-to-MeSH correspondence matrix, which has dimensionality T by M. Recall that we set T=M when running LDA. Next, we calculated the matrix product of M5 and M4 to get the D by M matrix M6, which is the same dimensionality as the Document-to-MeSH matrix, M1. Because M6 included both topic model and Topic-to-MeSH correspondence information, we named M6 our Document-to-TopicalMeSH matrix. Here we propose using this TopicalMeSH document representation for text mining tasks. Specifically, for our Evaluation, we evaluate the utility of the TopicalMeSH feature matrix M6 compared to the original MeSH features in Matrix M1 on two standard tasks: document retrieval and text classification.

Evaluation

For both tasks, we used 15 publicly available systematic drug review corpora [34]. Each corpus is a set of PubMed titles and abstracts for systematic literature reviews comparing classes of drugs used for treating specific conditions. The datasets include queries for randomized controlled trials by combining terms for health conditions and interventions with research methodology filters for therapies. Systematic reviewers read the titles and abstracts to assess which articles likely met the inclusion criteria for the corresponding review. This process is called citation screening, and is a laborious step in the systematic review process [35]. The articles deemed relevant by systematic reviewers during this citation screening process constitute the positive instances for each corpus. Here we use only the PubMed citation data, not the full text articles. More details about these data are available in [34].

Table 1 provides a brief description of the 15 drug review corpora that we used here. For the number of unique MeSH terms, we simply took observed MeSH descriptors into consideration and only count those MeSH Terms indexed in more than 10 documents.

Table 1. Systematic Drug Review Corpora Description.

| Drug Review Name | No of Articles | % of judged relevant articles | No of Unique MeSH Terms | No of MeSH Per Doc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | 2544 | 1.6 | 333 | 12 |

| ADHD | 851 | 2.4 | 155 | 11 |

| Antihistamines | 310 | 5.2 | 57 | 9 |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | 1120 | 13.0 | 155 | 11 |

| Beta Blockers | 2072 | 2.0 | 336 | 13 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 1218 | 8.2 | 197 | 12 |

| Estrogens | 368 | 21.7 | 79 | 10 |

| NSAIDS | 393 | 10.4 | 80 | 12 |

| Opiods | 1915 | 0.8 | 273 | 12 |

| Oral Hypoglycemics | 503 | 27.0 | 90 | 12 |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | 1333 | 3.8 | 165 | 13 |

| Skeletal Muscle Relaxants | 1643 | 0.5 | 236 | 8 |

| Statins | 3465 | 2.5 | 447 | 11 |

| Triptans | 671 | 3.6 | 78 | 9 |

| Urinary Incontinence | 327 | 12.2 | 55 | 8 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

For the document retrieval task, we compared TopicalMeSH and MeSH's performance on retrieving relevant documents in each of the 15 drug review corpora. We mapped the drug names to relevant MeSH terms. Table 2 reports the details of drug names and their relevant MeSH Terms. We used the online MeSH Browser (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/2015/mesh_browser/MBrowser.html) to find each drug's relevant MeSH terms first. Each drug may have multiple relevant MeSH terms and some MeSH terms may have several children terms under the MeSH tree structure. For each drug, we then picked the single term that achieved the best retrieval performance (measured using F-score) from its relevant MeSH terms and their children terms if any. For example, ‘Antihistamines’ can be mapped to MeSH term ‘Histamine Antagonists’ using MeSH browser. ‘Histamine Antagonists’ has several children terms, ‘Histamine H1 Antagonists’, ‘Histamine H2 Antagonists’, and ‘Histamine H3 Antagonists’. ‘Histamine H1 Antagonists’ achieved a higher F-score than ‘Histamine Antagonists’ based on ‘Antihistamines’ corpus. Hence we choose ‘Histamine H1 Antagonists’ as its relevant MeSH term for this document retrieval task.

Table 2. Relevant MeSH Terms for Drugs.

| Drug Review Name | Relevant MeSH |

|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity |

| Antihistamines | Histamine H1 Antagonists |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | Antipsychotic Agents |

| Beta Blockers | Adrenergic beta-Antagonists |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | Calcium Channel Blockers |

| Estrogens | Estrogen Replacement Therapy |

| NSAIDS | Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal |

| Opioids | Analgesics, Opioid |

| Oral Hypoglycemics | Hypoglycemic Agents |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | Proton Pump Inhibitors |

| Skeletal Muscle Relaxants | Muscle Relaxants, Central |

| Statins | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors |

| Triptans | Sumatriptan |

| Urinary Incontinence | Urinary Incontinence |

To reduce matrix sparsity, we used only MeSH main headings. We compared those MeSH terms' document retrieval performance using the rows of matrix M1 and those of M6 in Figure 2. M1 records whether or not each MeSH term has been assigned to each document, so those documents already annotated with the MeSH term (or terms) used in the query will be retrieved as relevant. M6 provides a mapping between terms in the MeSH vocabulary and the topics inferred by LDA, such that those documents in which topics corresponding to the MeSH term (or terms) in the query were ranked highest. The salient question was whether using the latter improves performance over the corresponding MeSH term. Although most real-world queries typically use more than one MeSH term or a combination of MeSH terms and other features, we used only the corresponding MeSH term, because our goal was to determine whether topic models could improve the utility of MeSH terms.

For the MeSH representation, we calculated a single pair of precision and recall scores (Equations 3 and 4) based on the binary matrix M1. For the TopicalMeSH representation, we ranked those documents based on TopicalMeSH's weights in matrix M6 and drew a precision-recall curve, in which the recall ranges from 10% to 100%. We computed both overall average and individual precision and recall for these 15 corpora. The overall average is just the arithmetic mean of the 15 individual precisions and recalls for these corpora.

In the classification task, we applied supervised machine learning methods to the corpus in an effort to learn to classify documents in the data sets with respect to their inclusion (1) or exclusion (-1) during citation screening. We used 80% of the documents in the data sets as training data and 20% as test data. We then evaluated three models that leveraged different document representations as feature vectors: a linear kernel Support Vector Machine (SVM), logistic regression with an L2 penalty for coefficient regularization, and a decision tree. Using these models, we compared the following five different representations: MeSH, TopicalMeSH, Words, MeSH+Words, TopicalMeSH+Words. The Words representation used the ‘bag of words’ assumption with each word reweighted using the tf-idf measure (Equations 1). These three machine learning algorithms are implemented in the Python machine learning package scikit-learn [36]. For the linear kernel SVM, we gave more importance to the relevant documents class with the class-weight setting as 1:c, where c is the proportion of the irrelevant documents to the relevant in each corpus. For the logistic regression, we used the L2 penalty with the regularization parameter C ranging from 0.01 to 1000 with the exponent base of 10. We report the best results. For the decision tree, we used the default settings.

In addition, we also compared our TopicalMeSH's performance in the classification task to the topic representation (Matrix 4 in figure 2) generated from LDA (Topic), tf-idf weighted MeSH, and a combination of topic representation and MeSH representation (Topic + MeSH) using SVMs. Besides, supervised LDA (sLDA) [37]'s document classification performance was also added into this comparison. sLDA is a supervised topic model for labeled documents, in which a response variable (label) associated with each document is accommodated comparing to LDA. For sLDA, we used 80% of the documents in the data sets to train sLDA and then used the trained model to infer the rest of the documents' labels (relevant or irrelevant). We used the same number of topics in sLDA as we used in LDA. We set the the convergence criteria for variational EM to 0.0001 and the maximum number of iterations of variational EM to 70. And we also set the L2 penalty in sLDA to 0.01. In our experiments, the convergence criteria was met across all corpora within 70 iterations. For Topic and Topic+MeSH representations, we used SVMs as the classifier in this task.

For all models, we used stratified 5 fold validation to assess performance. We used 5 fold (rather than 10 fold or leave-one-out cross fold validation) as a practical means to mitigate compute time: recall that we have 15 corpora and most of them have more than 1000 documents. We also use 3 classification methods. Within each method, we tested 5 different representations. For each of these, we trained and evaluated the machine learning algorithms with each feature set using the other four folds as training data. We averaged performance over these five folds to assess performance. For this task, we used the following evaluation metrics: precision(P), recall(R), and balanced F-score (F1). These measures are defined as:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where TP, FP and FN denote true positive, false positive and false negative counts, respectively.

4 Results

Result of Document Retrieval Task

Figure 3 provides graphical comparisons between the precision-recall curve of TopicalMeSH and the single precision-recall point of MeSH for these 15 corpora. TopicalMeSH achieved higher precision scores in 11 of 15 corpora with the same recall as achieved using MeSH. In addition, in 14 out of 15 corpora TopicalMesh can achieve better recall while achieving precision that is similar to MeSH.

Figure 3.

Individual Precision and Recall of 15 Corpora.

Figure 4 provides a comparison of the overall average precision and recall between MeSH and TopicalMeSH over these 15 corpora. We can see that MeSH is clearly under TopicalMeSH's precision-recall curve. The improvement of overall precision from MeSH to TopicalMeSH is about 5% (absolute) with the same recall of MeSH's.

Figure 4.

Overall Average Precision and Recall of 15 Corpora.

Result of Classification Task

To measure classification performance, we used F-score (Equation 5), the harmonic mean of precision and recall. We note that in practice, one would be much more concerned with recall than precision for the task of automated citation screening, as one aims to be comprehensive when conducting systematic reviews [35]. However, here we are using this as simply an illustrative biomedical text classification task; our focus is not specifically on the citation screening problem. Tables 3, 4, and 5 show the results of comparisons among the representations, MeSH, TopicalMeSH, Words, MeSH+Words, TopicalMeSH+Words, using the SVM, logistic regression, and the decision tree models, respectively. Table 6 shows the results of comparisons among the Topics, Topics+MeSH, and TopicalMeSH representations (all using SVM), as well as sLDA.

Table 3. F-scores of Support Vector Machines.

| Drug Review Name | MeSH | TopicalMeSH | tf-idf Words | MeSH+Words | TopicalMeSH+Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | 9.28% | 33.2% | 20% | 17.7% | 25.7% |

| ADHD | 51.8% | 61.2% | 30.5% | 53.7% | 49.6% |

| Antihistamines | 58.4% | 40% | 27.1% | 53.1% | 35.5% |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | 37.1% | 58.2% | 53.7% | 44.5% | 56.2% |

| Beta Blockers | 26.5% | 38.8% | 32.2% | 29.6% | 36.7% |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 16.7% | 56.8% | 43.8% | 36.5% | 50.5% |

| Estrogens | 27.8% | 56.9% | 22.8% | 29% | 36.6% |

| NSAIDS | 31.7% | 56% | 46.3% | 36.3% | 50.9% |

| Opiods | 7.8% | 11.3% | 4% | 10.7% | 4% |

| Oral Hypoglycemics | 40% | 55.3% | 29.2% | 45.3% | 48.6% |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | 26.1% | 43.7% | 33.6% | 26.4% | 37.5% |

| Skeletal Muscle Relaxants | 0 | 15.5% | 26.3% | 0 | 29.8% |

| Statins | 6.3% | 24.9% | 18.2% | 12.4% | 19% |

| Triptans | 56.8% | 65.2% | 63.3% | 59.6% | 64.9% |

| Urinary Incontinence | 42.65% | 50.46% | 12% | 52.57% | 33.63% |

| Macro-Average F-score | 29.26% | 44.5% | 30.86% | 33.82% | 38.61% |

Boldface numerals on the left show the best results for TopicalMeSH vs. MeSH, whereas those on the right highlight the best performance for MeSH+Words vs. TopicalMeSH+Words.

Table 4. F-Scores of Logistic Regression.

| Drug Review Name | MeSH | TopicalMeSH | tf-idf Words | MeSH + Words | TopicalMeSH + Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | 6.2% | 18.8% | 17.2% | 13.7% | 23.1% |

| ADHD | 49.1% | 44.6% | 19.8% | 56.9% | 50.9% |

| Antihistamines | 56.2% | 27.1% | 24.2% | 53.9% | 32.3% |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | 24.7% | 52.4% | 54.5% | 43.5% | 57.2% |

| Beta Blockers | 20.6% | 27.1% | 25.1% | 27.1% | 33.7% |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 16.6% | 45.5% | 40.2% | 33.9% | 48.5% |

| Estrogens | 25.7% | 45.1% | 15.1% | 30.7% | 34.4% |

| NSAIDS | 26% | 55.7% | 38% | 34.1% | 53.6% |

| Opiods | 12.3% | 6.7% | 0 | 3.3% | 0 |

| Oral Hypoglycemics | 41.5% | 48.7% | 26.3% | 45.1% | 48.2% |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | 10.8% | 31.9% | 31.7% | 24.2% | 35.4% |

| Skeletal Muscle Relaxants | 0 | 0 | 20.7% | 0 | 10.7% |

| Statins | 2.8% | 16.4% | 12.2% | 8.1% | 16.3% |

| Triptans | 54.9% | 61.9% | 62.4% | 59.5% | 65.8% |

| Urinary Incontinence | 41.5% | 54.19% | 4% | 36.56% | 26.02% |

| Macro-Average F-score | 27.88% | 38.71% | 28.15% | 31.37% | 35.74% |

Boldface numerals on the left show the best results for TopicalMeSH vs. MeSH, whereas those on the right highlight the best performance for MeSH+Words vs. TopicalMeSH+Words.

Table 5. F-Scores of Decision Tree.

| Drug Review Name | MeSH | TopicalMeSH | tf-idf Words | MeSH+Words | TopicalMeSH+Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | 5% | 17.5% | 22.2% | 22.9% | 20.5% |

| ADHD | 46.3% | 38.5% | 39.7% | 49.5% | 41.7% |

| Antihistamines | 39.2% | 38.5% | 47.9% | 48.5% | 44.8% |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | 34.5% | 42.7% | 47.2% | 45.8% | 46.2% |

| Beta Blockers | 17.5% | 19.7% | 29% | 30.2% | 30.4% |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 26.8% | 41.2% | 43.5% | 42.3% | 43.1% |

| Estrogens | 24.3% | 34.4% | 37.1% | 39.6% | 39% |

| NSAIDS | 20.9% | 42.2% | 57.7% | 56.2% | 53.1% |

| Opiods | 5% | 9% | 6.5% | 1.7% | 7.9% |

| Oral Hypoglycemics | 39.2% | 43.7% | 44.6% | 41.2% | 39.7% |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | 19.7% | 28.9% | 31.5% | 31% | 30.7% |

| Skeletal Muscle Relaxants | 2.9% | 12% | 19.5% | 19% | 24.8% |

| Statins | 5.7% | 11.8% | 14% | 14.5% | 14.2% |

| Triptans | 48.6% | 49.6% | 56.7% | 58.2% | 57.1% |

| Urinary Incontinence | 40.67% | 36.05% | 40.07% | 32.53% | 33.45% |

| Macro-Average F-score | 25.08% | 31.05% | 35.81% | 35.54% | 35.11% |

Boldface numerals on the left show the best results for TopicalMeSH vs. MeSH, whereas those on the right highlight the best performance for MeSH+Words vs. TopicalMeSH+Words.

Table 6. Comparison to tf-idf MeSH and sLDA.

| Drug Review Name | tf-idf MeSH | Topics | Topics+MeSH | TopicalMeSH | sLDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | 8.5% | 24.7% | 16.7% | 33.2% | 5.1% |

| ADHD | 44.2% | 53.4% | 43.6% | 61.2% | 14.4% |

| Antihistamines | 57% | 44.6% | 44.7% | 40% | 13.2% |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | 37.3% | 55% | 47.3% | 58.2% | 43.6% |

| Beta Blockers | 23.3% | 32.8% | 29.8% | 38.8% | 12.9% |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 29% | 46.9% | 39.7% | 56.8% | 29.2% |

| Estrogens | 26.4% | 43.8% | 38.8% | 56.9% | 21% |

| NSAIDS | 31.9% | 46.4% | 44.1% | 56% | 37.1% |

| Opiods | 10.7% | 9.3% | 8.8% | 11.3% | 0 |

| Oral Hypoglycemics | 41.8% | 49.7% | 44% | 55.3% | 31.6% |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | 26% | 40.3% | 33.2% | 43.7% | 29.9% |

| Skeletal Muscle Relaxants | 2% | 9.5% | 10.2% | 15.5% | 0 |

| Statins | 6.3% | 20.3% | 14.9% | 24.9% | 12% |

| Triptans | 55.5% | 66.7% | 60.9% | 65.2% | 63% |

| Urinary Incontinence | 39% | 38% | 51.2% | 50.46% | 20.2% |

| Macro-Average F-score | 29.26% | 38.76% | 35.19% | 44.5% | 22.21% |

The best score for each corpus is shown in boldface.

In general, SVM achieved the best performance on the test data. Decision trees had the worst performance on most of these corpora, but performed well when there were a very small fraction of relevant documents. Overall, TopicalMeSH achieved a higher F-score in 14 of 15 corpora using SVMs, 12 of 15 corpora using logistic regression, and 12 of 15 corpora using decision trees. We also combined the Words features with both MeSH and TopicalMeSH. By using SVMs or (regularized) logistic regression, TopicalMeSH+Words had a higher F-score than MeSH+Words in 11 of 15 corpora from both table 3 and table 4. However in Table 5 shows that the performance of TopicalMeSH+Words and MeSH+Words were very close to each other using decision trees.

In Table 6, TopicalMeSH achieved a higher F-score in 12 of 15 corpora. Topics representation had better performance than tf-idf weighted MeSH terms and sLDA.

5 Discussion

TopicalMeSH representations outperformed those using only MeSH terms for both the document retrieval and classification tasks. TopicalMeSH can assess each MeSH term's weight for each document and also (implicitly) assign MeSH terms to documents that may be missing some relevant MeSH terms. One of the challenges with making practical use of topic models is that users often do not understand what each topic “means” since the topics are distributions over words, not a single understandable word or phrase that summarizes the concept. TopicalMesh effectively solves this problem by associating topics with corresponding MeSH terms. This provides a convenient and familiar terminology to present to users.

The current work has several limitations. First, in general the performance of LDA is highly dependent on the number of topics set by the user. Here we did not use a formal approach to set this number, but rather used the number of MeSH terms as the number of topics when running LDA. This is a practical strategy that is intuitively agreeable, but determining the optimal number of topics for each corpus is challenging and may depend on the needs of the end user. For example, a smaller number of topics tends to identify more general themes, whereas larger numbers uncover more specific themes. Additional work is needed to assess how the number of topics affects the performance of the TopicalMeSH representation. Another limitation is that MeSH terms that index only a small number of documents in the corpus have very low correspondence scores to all topics. This arises because the MeSH-to-Topic correspondence matrix is based on the topic-to-Word and MeSH-to-Word distributions. Although we only consider MeSH terms indexing more than 10 documents in a corpus, there are many MeSH terms just above this threshold that have very sparse co-occurrence word distributions, leading to low correspondence scores between these MeSH terms and all topics. One possible solution to this problem is to use the full text documents, or additional documents (outside the corpus) that use these MeSH terms, to create the MeSH-to-Word distribution. Finally, all of the corpora in our evaluation was limited to systematic drug review articles, which tend to have fairly homogeneous content. Although our approach is applicable to all types of queries, we have not yet evaluated it on queries that produce more heterogeneous articles (such as free-text term searches).

For the document retrieval task, TopicalMeSH outperformed MeSH in 14 of 15 corpora. MeSh terms are created and maintained by domain experts to cover all general important themes. Our TopicalMeSH combines both the information of human judgment and the semantic information, induced by topic models, that is specific to this subset of documents. This is why TopicalMeSH has better performance in general. However, we found that MeSH's precision-recall points were very close to TopicalMeSH's precision-recall curves for the highly imbalanced corpora, such as Beta Blockers, Opiods, and Skeletal Muscle Relaxants. This is likely because we used only titles and abstracts to perform the evaluations, whereas MeSH is based on the entire document. The small portion of relevant abstracts may not be enough to create the relevant MeSH term's semantic words distributions that could distinguish them from the other MeSH terms. It is also difficult for topic models to uncover latent topics to cluster a very small number of relevant articles. Hence, using those MeSH terms to find the corresponding latent topics to retrieve the relevant documents could bring in even more bias. For corpora with higher proportions of relevant articles, such as Estrogens, NSAIDS and Urinary Incontinence, TopicalMeSH performed much better than MeSH.

In the classification task, TopicalMeSH achieved a higher F-score than MeSH in general. The words feature had the worst F-score performance on these corpora using these three machine learning methods. The reason may be that the words are derived only from titles and abstracts (ignoring the MeSH information and hence information gleaned from the full texts). When we added the Words feature to both MeSH and TopicalMeSH, the latter still yielded a better performance than MeSH for most of the corpora when we used SVMs and logistic regression. In general, decision trees are not well-suited to text classification and placed too much weight on the words feature. This is why the performance of MeSH+Words and TopicalMeSH+Words in Table 5 were close to each other. This demonstrates the potential of combining topic models with MeSH to induce a useful representation. TopicalMeSH is one realization of this idea. For this application, sLDA fares poorly; this may be due in part to sLDA not accounting for class imbalance.

Our approach depends on having documents already indexed with MeSH terms. We use these to both set the number of topics and to choose the corresponding topic in the information retrieval task. From a practical perspective, this is not a problem for augmenting a search tool, such as PubMed with topic models to improve search results; however, this limits the applicability of our approach to corpora that are already indexed with controlled terms. Our code and evaluation data can be found here (https://github.com/Ssssssstanley/topicalmesh.git).

In the future, we plan to evaluate TopicalMeSH representation's performance in different information retrieval models and explore other potential benefits that topic models may have over MeSH Terms. Topic models may provide an alternative view for better ranking, clustering, and summarizing relevant documents. Since topic models can identify themes in a corpus from the data itself, they may reveal insights and emerging themes that are not yet present in MeSH. Finally, we are exploring user-driven feedback to help customize topic models to each users' information needs, as well as interactive visualizations of topic models of query result sets.

6 Conclusions

We explored whether vector representations that encode latent topic proportions that capture similarities to MeSH terms (the TopicalMeSH representation) could improve performance on document retrieval and classification tasks, compared to using MeSH terms.

We found that latent topics that correspond to MeSH terms improve information retrieval and document classification performance for PubMed abstracts. With the increasing growth of electronic sources, interactive tools that facilitate information retrieval and knowledge discovery will only increase in importance. Topic models are an important class of approaches that warrant further research bridging theory and practical application.

Highlights.

We introduce a novel representation, TopicalMeSH, by leveraging both probability topic models and MeSH terms

TopicalMeSH has better document retrieval performance than MeSH

TopicalMeSH can achieve a better document classification performance when compared to MeSH, bag of words, a combination of MeSH and words, tf-idf weighted MeSH, and supervised latent dirichet allocation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the UTHealth Innovation for Cancer Prevention Research Training Program Predoctoral Fellowship (Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant # RP140103). This work was also supported by the Brown Foundation, NIH NCATS grant UL1 TR000371 and NIH NCI grant U01 CA180964. Wallace's effort was partially supported by NIH/NLM grant R01 LM012086. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the CPRIT or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Zhiguo Yu, School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Elmer Bernstam, School of Biomedical Informatics and Department of Internal Medicine, Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Trevor Cohen, School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Byron C. Wallace, School of Information, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA.

Todd R. Johnson, School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

References

- 1.Lu Z, Kim W, Wilbur WJ. Evaluation of query expansion using MeSH in PubMed. Information retrieval. 2009;12(1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10791-008-9074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter RR, Austin TM. Using MeSH (medical subject headings) to enhance PubMed search strategies for evidence-based practice in physical therapy. Physical therapy. 2012;92(1):124–132. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdou S, Savoy J. Searching in Medline: Query expansion and manual indexing evaluation. Information Processing & Management. 2008;44(2):781–789. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu Z. PubMed and beyond: a survey of web tools for searching biomedical literature. Database: the journal of biological databases and curation. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1093/database/baq036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkar IN, Schenk R, Miller H, Norton CN. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. Vol. 2009. American Medical Informatics Association; 2009. LigerCat: using ‘MeSH clouds’ from journal, article, or gene citations to facilitate the identification of relevant biomedical literature; p. 563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theodosiou T, Vizirianakis I, Angelis L, Tsaftaris A, Darzentas N. MeSHy: Mining unanticipated PubMed information using frequencies of occurrences and concurrences of MeSH terms. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2011;44(6):919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang M, Névéol A, Lu Z. Recommending MeSH terms for annotating biomedical articles. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011 doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000055. amiajnl–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavuluru R, He Z. Natural Language Processing and Information Systems. Springer; 2013. Unsupervised Medical Subject Heading Assignment Using Output Label Co-occurrence Statistics and Semantic Predications; pp. 176–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronson AR, Mork JG, Gay CW, Humphrey SM, Rogers WJ. The NLM indexing initiative's medical text indexer. Medinfo. 2004;11(Pt 1):268–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasuki V, Cohen T. Reflective Random Indexing for Semi-automatic Indexing of the Biomedical Literature. J of Biomedical Informatics. 2010 Oct;43(5):694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funk ME, Reid CA. Indexing consistency in MEDLINE. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 1983;71(2):176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NLM. MEDLINE Data Changes. 2015 Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/techbull/nd14/nd14_medline_data_changes_2015.html.

- 13.Srinivasan P. Text mining: generating hypotheses from MEDLINE. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2004;55(5):396–413. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan P. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium. American Medical Informatics Association; 2001. MeSHmap: a text mining tool for MEDLINE; p. 642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blei DM. Probabilistic topic models. Commun ACM. 2012 Apr;55(4):77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Z, Johnson TR, Kavuluru R. Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), 2013 12th International Conference on. Vol. 1. IEEE; 2013. Phrase Based Topic Modeling for Semantic Information Processing in Biomedicine; pp. 440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang J, Gerrish S, Wang C, Boyd-graber JL, Blei DM. Reading tea leaves: How humans interpret topic models. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2009:288–296. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuang J, Gupta S, Manning C, Heer J. Topic model diagnostics: Assessing domain relevance via topical alignment. Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-13) 2013:612–620. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Xp, Zhou Xz, Huang Hk, Feng Q, Chen Sb, Liu By. Topic model for chinese medicine diagnosis and prescription regularities analysis: case on diabetes. Chinese journal of integrative medicine. 2011;17:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao L, Zhang Y, Wei B, Wang W, Zhang Y, Ren X. Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2014 IEEE International Conference on. IEEE; 2014. Discovering treatment pattern in traditional Chinese medicine clinical cases using topic model and domain knowledge; pp. 191–192. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkins D, Rubin T, Steyvers M, Doeden M, Baucom B, Christensen A. Topic Models: A Novel Method for Modeling Couple and Family Text Data. Journal of family psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43) 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0029607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehman Lw, Saeed M, Long W, Lee J, Mark R. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. Vol. 2012. American Medical Informatics Association; 2012. Risk Stratification of ICU Patients Using Topic Models Inferred from Unstructured Progress Notes; p. 505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold CW, Oh A, Chen S, Speier W. Evaluating Topic Model Interpretability from a Primary Care Physician Perspective. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2016 Feb;124(C):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.10.014. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin CX, Zhao B, Mei Q, Han J. Proceedings of the 16th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining. ACM; 2010. PET: a statistical model for popular events tracking in social communities; pp. 929–938. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul MJ, Dredze M. Discovering health topics in social media using topic models. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Agichtein E, Benzi M. Proceedings of the 18th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining. ACM; 2012. TM-LDA: efficient online modeling of latent topic transitions in social media; pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramage D, Hall D, Nallapati R, Manning CD. Labeled LDA: A Supervised Topic Model for Credit Attribution in Multi-labeled Corpora; Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Volume 1 - Volume 1. EMNLP '09; Stroudsburg, PA, USA. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2009. pp. 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu D, Li D, Carterette B, Liu H. An Incremental Approach for MEDLINE MeSH Indexing. BioASQ@CLEF vol 1094 of CEUR Workshop Proceedings. 2013 CEUR-WS.org.

- 29.Newman D, Karimi S, Cavedon L. AI 2009: Advances in Artificial Intelligence. Springer; 2009. Using topic models to interpret MEDLINE's medical subject headings; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bundschus M, Tresp V, Kriegel HP. Topic models for semantically annotated document collections. NIPS workshop: Applications for Topic Models: Text and Beyond. 2009:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.He D. Modeling semantic influence for biomedicai research topics using MeSH hierarchy. Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2012 IEEE International Conference on IEEE. 2012:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doshi-Velez F, Wallace B, Adams R. Graph-Sparse LDA: A Topic Model with Structured Sparsity. Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2015;1050:21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI. Latent dirichlet allocation. J Mach Learn Res. 2003 Mar;3:993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen AM, Hersh WR, Peterson K, Yen PY. Reducing workload in systematic review preparation using automated citation classification. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2006;13(2):206–219. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace BC, Trikalinos TA, Lau J, Brodley C, Schmid CH. Semi-automated screening of biomedical citations for systematic reviews. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. The Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mcauliffe JD, Blei DM. Supervised topic models. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2008:121–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]