Abstract

Objective

To identify baseline characteristics of couples likely to predict conception, clinical pregnancy, and live-birth following up to four cycles of ovarian stimulation with intrauterine insemination in couples with unexplained infertility.

Design

Secondary analyses of data from a prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial investigating pregnancy, live-birth, and multiple pregnancy rates following ovarian stimulation-intrauterine insemination with clomiphene citrate, letrozole, or gonadotropins.

Setting

Outpatient clinical units associated with the Reproductive Medicine Network clinical sites

Patients

Nine-hundred couples with unexplained infertility who participated in the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) clinical trial.

Intervention

As part of the clinical trial, treatment was randomized equally to one of three arms and continued for up to four cycles or until pregnancy was achieved.

Main outcomes measures

Conception, clinical pregnancy and live-birth rates.

Results

In a multivariable logistic regression analysis, after adjustment for other covariates, age, waist circumference, income level, duration of infertility, and a history of prior pregnancy loss were significantly associated with at least one pregnancy outcome. Other baseline demographic and lifestyle characteristics including smoking, alcohol use, and serum levels of AMH, were not significantly associated with pregnancy outcomes.

Conclusions

While age and duration of infertility were significant predictors of all pregnancy outcomes, many other baseline characteristics were not. The identification of level of income as a significant predictor of outcomes independent of race and education may reflect differences in the underlying etiologies of unexplained infertility or could reveal disparities in access to fertility and/or obstetrical care.

Keywords: Unexplained infertility, predictors, ovarian stimulation, intrauterine insemination, pregnancy

Introduction

Infertility is one of the most common medical problems affecting reproductive age adults (1). Although the estimated prevalence is between 10–15%, the true prevalence is likely greater due to the social stigma associated with this diagnosis (2,3). In couples experiencing infertility, it has been estimated that between 15–37% have infertility with no identifiable etiology (4,5). Treatment paradigms for unexplained infertility typically involve ovarian stimulation (OS) with intrauterine insemination (IUI), subsequently followed by in-vitro fertilization (IVF) for those unsuccessful in achieving pregnancy with OS-IUI (6). Unfortunately, less than one-third of couples will achieve a live-birth following the most aggressive OS-IUI treatments involving gonadotropins, and will therefore require IVF (7,8).

Previous investigations have evaluated the relationship between lifestyle and socioeconomic factors and pregnancy outcomes following treatment in couples with unexplained infertility (9,10). Many of these investigations have relied on retrospective data, have not included the outcome of live-birth, or have focused on outcomes in the setting of IVF rather than OS-IUI (9,11–15). One of the largest investigations, which included 664 couples with unexplained infertility, 164 of whom underwent up to four cycles of OS-IUI treatment, has suggested that the former use of coffee, tea, and alcohol was associated with greater pregnancy and live-birth rates as compared to never and current users (10).

Since OS-IUI and IVF are personally demanding, resource intensive, and are not without expense and risk, identification of patient characteristics associated with successful treatment outcomes following OS-IUI may allow for more effective counseling and treatment planning. Our hypothesis was that baseline characteristics of the couple, including lifestyle factors, would predict treatment outcomes. To this end, the present investigation sought to 1) identify risk factors associated with treatment outcomes, and 2) develop prediction models of treatment outcomes following OS-IUI treatment applied to the Reproductive Medicine Network’s the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) clinical trial. This trial, conducted at twelve clinical sites, randomized 900 couples with unexplained infertility to clomiphene, letrozole, or gonadotropins treatment for OS-IUI (8).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This secondary analysis included all 900 participants from The AMIGOS clinical trial. The trial design, analysis plan, baseline characteristics of the participating couples as well as the trial outcomes have previously been published (8,16). Briefly, the AMIGOS trial was a prospective, multicenter randomized clinical trial which evaluated the outcomes of conception, pregnancy, live-birth and multiple gestations associated with OS-IUI in couples with unexplained infertility. The trial was conducted at twelve clinical locations in the United States, with the clinicaltrials.gov number NCT01044862. Treatment arms included clomiphene citrate (300 couples), letrozole (299 couples), and gonadotropin (Menopur®, Ferring Pharmaceuticals; 301 couples). Couples underwent OS-IUI treatment in the assigned arm until four cycles were completed or pregnancy occurred. Participating women were ≥18 to ≤ 40 years with regular menses, had a normal uterine cavity with at least one patent fallopian tube, and a male partner with a semen specimen with at least 5 million motile sperm in the ejaculate. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each study site and all participants underwent the written informed consent process. The investigation was monitored by a Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Methods

Baseline demographics as well as a complete medical and fertility history were obtained using standardized forms upon enrollment for all participants (16). AMH assays were completed on fasting samples, and batched samples were analyzed at the Ligand Assay & Analysis Core Laboratory at the University of Virginia (16). Intra and inter assay coefficients of variation were 3% and 7%, respectively.

Data Analyses

Outcomes of interest for this study are conception, pregnancy (clinical), and live birth. For the AMIGOS trial, conception was defined as having a rising serum level of human chorionic gonadotropin on two consecutive tests. Clinical pregnancy was defined as an intrauterine pregnancy with fetal heart motion as detected by transvaginal ultrasound. Live birth was defined as the delivery of a viable infant.

Baseline patient demographic information and biochemical markers were selected as predictor variables. These variables include: treatment group, age, body-mass-index (BMI, both female and male), waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, race, ethnicity, smoking, alcohol use, income, education level, duration of infertility, total-motile sperm count in the screening semen analysis (TMC), prior conception, prior pregnancy loss, prior parity, prior infertility therapy, serum AMH concentration, and the emotional domain score of the Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQol) survey (17,18) as a measure of psychosocial stress. All variables were evaluated as continuous predictors for modeling purposes with the exception of BMI and income. BMI was categorized as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–30 kg/m2) and obese (>30 kg/m2) given that underweight and overweight status may each be associated with poorer treatment outcomes. Income was categorized as <$50,000 and ≥$50,000 and refused to answer. Waist circumference was modeled as both a continuous variable and categorically (<=88 cm and > 88 cm) given that 88 cm is a commonly recognized cut-point for abdominal adiposity associated with significantly increased metabolic risk (19,20). For summary statistics, ANOVA, Students t-test, chi-square analyses, and Fisher exact tests or other nonparametric equivalent tests were used to compare each outcome to the putative predictors depending on the type (continuous or categorical) and distribution (normal or not) of a predictor.

Logistic regression was used to establish a prediction model using all the predictors listed above for each outcome variable. All variables were introduced to a multivariable logistic regression analysis in a stepwise fashion, using a p value of <0.10 to enter and p value of <0.05 to remain. Treatment group was retained in the final model regardless of significance. For each covariate selected from the stepwise procedure, the interaction effects between the treatment (as a whole) and the selected covariates were assessed, and those interactions that were significant at the 0.05 level were included in the final models. All analyses were adjusted by treatment site. For each outcome, we present tables with odds ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for all predictors for both unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analysis.

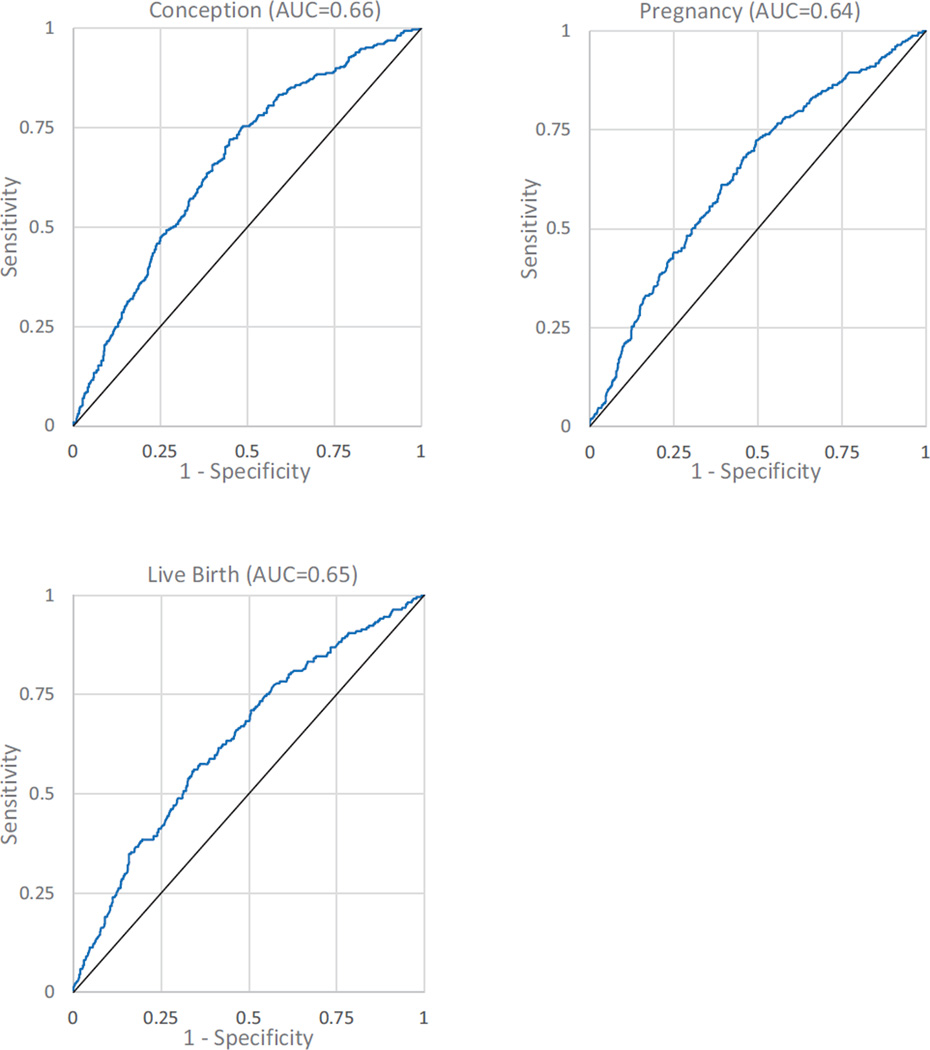

To assess the predictive power of final models, we constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculated the areas under them (AUC). We also performed the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (21) for goodness-of-fit of the final logistic regression models, with a p-value of >0.05 indicating a good fit of the data. SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline clinical, demographic, and AMH levels are presented for the 900 couples who participated in the AMIGOS trial in Supplemental Table 1. Beyond the significant differences noted in outcomes based upon treatment group as previously reported (8), significant differences were also observed in some baseline characteristics between patients who achieved conception, clinical pregnancy, and live-birth and those who did not. Age was significantly lower in women who achieved a clinical pregnancy (31.7 vs. 32.5 years, p = 0.016) and live-birth (31.5 vs. 32.5 years, p = 0.003) compared to those who did not. A waist circumference of > 88 cm was associated with a higher rate of conception compared to a waist circumference of ≤ 88 cm (41.0% vs. 34.4%, p = 0.046), but not associated with a difference in the rate of live-birth, although there was a non-significantly higher rate of clinical pregnancy loss in the > 88 cm group (18.0% > 88 cm waist circumference group vs. 10.8% ≤ 88 cm group, p = 0.105). HOMA-IR was greater in those participants with a waist circumference of > 88 cm than those with a circumference of ≤ 88 cm (3.29 [95%CI 2.77,3.80] vs. 1.28 [95%CI 1.11,1.44]; p < 0.001). However, HOMA-IR was not associated with conception, clinical pregnancy or live-birth. Serum levels of AMH were not significantly different between the two waist circumference groups (data not shown). When waist circumference was evaluated as a continuous variable there were no significant associations with treatment outcomes (Supplemental Table 1).

The duration of infertility was significantly shorter in those who achieved a conception (30.4 vs. 37.2 months, p < 0.001), clinical pregnancy (30.4 vs. 36.5 months, p < 0.001) and live-birth (30.2 vs. 36.2 months, p = 0.003) as compared to those who did not. A history of prior conception and a prior pregnancy loss were more common in those achieving conception and clinical pregnancy, but not live-birth (Supplemental Table 1). Income of <$50,000 was more common in those who did not achieve a live-birth (16.4% vs. 26.4%, <$50,000 vs. ≥$50,000, respectively; p = 0.033). To a large extent, this difference in live-birth rate was due to a greater rate of clinical pregnancy loss in the <$50,000 income group vs. the >$50,000 income group (28% vs. 11%, respectively, p = 0.017). AMH levels were significantly different between those who did and did not achieve a conception and live-birth over the course of the trial (Supplemental Table 1).

Bivariate Analyses

The association between baseline characteristics and pregnancy outcomes in unadjusted analyses are presented in Table 1. Greater age was associated with significantly reduced odds for clinical pregnancy and live-birth. Waist circumference of ≥ 88 cm was associated with greater odds for conception, but not clinical pregnancy or live birth (Table 1). However, when evaluated as a continuous variable, waist circumference was not significantly associated with any pregnancy outcome. Black race was associated with lower odds of live-birth, but not conception or pregnancy. Income of ≥ $50,000 was associated with a greater odds of conception and live-birth as compared to income of <$50,000. Those participants that declined to answer the income question had increased odds of live-birth as compared to the lower income group. A longer duration of infertility was associated with lower conception, pregnancy and live-birth rate (Table 1). Prior conception and prior pregnancy loss were both associated with increased odds of conception and clinical pregnancy (Table 1). Greater serum levels of AMH were associated with increased odds of conception and live birth (Table 1). The emotional domain score of the FertiQol survey was not significantly associated with pregnancy outcomes in the unadjusted analyses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Unadjusted odds ratios for predictors for conception, pregnancy, and live birth for AMIGOS subjects$

| Variables | Conception OR (95% CI) |

P-value | Pregnancy OR (95% CI) |

P-value | Live Birth OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Group (N = 900) | ||||||

| Letrozole | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Clomiphene | 1.40 (0.99–1.97) | 0.058 | 1.37 (0.95–1.98) | 0.096 | 1.32 (0.89–1.96) | 0.168 |

| Gonadotropin | 2.22 (1.58–3.11) | <.001 | 1.91 (1.33–2.74) | <.001 | 2.06 (1.41–3.01) | <.001 |

| Age (N = 900) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.078 | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.016 | 0.95 (0.91–0.98) | 0.003 |

| BMI (female, N = 900) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 0.90 (0.36–2.28) | 0.827 | 1.02 (0.39–2.70) | 0.967 | 0.49 (0.14–1.71) | 0.265 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 25–30 | 1.01 (0.72–1.41) | 0.974 | 0.93 (0.64–1.33) | 0.681 | 0.85 (0.58–1.24) | 0.400 |

| >30 | 1.24 (0.89–1.72) | 0.198 | 1.20 (0.85–1.69) | 0.309 | 1.11 (0.78–1.60) | 0.563 |

| BMI (male, N=865) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 0.93 (0.22–4.01) | 0.924 | 0.69 (0.14–3.53) | 0.659 | 0.37 (0.05–3.08) | 0.358 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 25–30 | 0.91 (0.64–1.30) | 0.596 | 0.85 (0.59–1.24) | 0.399 | 0.88 (0.60–1.30) | 0.529 |

| >30 | 0.86 (0.59–1.25) | 0.426 | 0.72 (0.48–1.07) | 0.104 | 0.77 (0.50–1.16) | 0.210 |

| Waist Circumference (cm, N = 899) | 1.01 (0.996–1.01) | 0.254 | 1.00 (0.995–1.01) | 0.398 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.758 |

| &Waist Circumference (cm, N = 899) | ||||||

| <=88 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| >88 | 1.32 (1.01–1.74) | 0.046 | 1.21 (0.90–1.62) | 0.204 | 1.07 (0.79–1.46) | 0.671 |

| Waist Hip Ratio (N = 899) | 2.91 (0.84–10.11) | 0.093 | 2.11 (0.57–7.80) | 0.264 | 1.36 (0.34–5.39) | 0.662 |

| Ethnicity (N = 900) | ||||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Latino or Hispanic | 0.82 (0.52–1.29) | 0.394 | 0.89 (0.55–1.43) | 0.622 | 0.92 (0.56–1.52) | 0.745 |

| Race (N = 900) | ||||||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Black | 0.93 (0.58–1.49) | 0.763 | 0.59 (0.34–1.04) | 0.067 | 0.52 (0.28–0.97) | 0.039 |

| Asian | 0.86 (0.49–1.50) | 0.593 | 0.73 (0.39–1.36) | 0.312 | 0.73 (0.38–1.41) | 0.348 |

| American Indian | 0.42 (0.09–1.99) | 0.273 | 0.59 (0.12–2.78) | 0.501 | 0.72 (0.15–3.40) | 0.673 |

| Native Hawaiian | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mixed Race | 1.32 (0.59–2.94) | 0.504 | 1.56 (0.69–3.53) | 0.284 | 1.61 (0.70–3.70) | 0.263 |

| Education (N = 900) | ||||||

| High School or Less | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| College or Some College | 1.23 (0.74–2.05) | 0.427 | 1.28 (0.74–2.22) | 0.378 | 1.19 (0.70–2.10) | 0.558 |

| Graduate Degree | 0.94 (0.54–1.63) | 0.815 | 0.90 (0.49–1.63) | 0.718 | 0.88 (0.47–1.64) | 0.679 |

| Income (N = 900) | ||||||

| <$50,000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| >=$50,000 | 1.53 (1.04–2.25) | 0.031 | 1.43 (0.94–2.17) | 0.091 | 1.83 (1.15–2.91) | 0.011 |

| Wish not to answer | 1.34 (0.83–2.16) | 0.226 | 1.42 (0.85–2.35) | 0.181 | 1.84 (1.06–3.21) | 0.032 |

| Smoking (N = 900) | ||||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Current | 1.31 (0.79–2.15) | 0.295 | 1.41 (0.85–2.37) | 0.187 | 1.27 (0.74–2.19) | 0.381 |

| Quit | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.427 | 0.85 (0.61–1.20) | 0.362 | 0.92 (0.65–1.31) | 0.653 |

| Alcohol (N = 900) | ||||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Current | 1.33 (0.86–2.06) | 0.198 | 1.41 (0.87–2.27) | 0.159 | 1.66 (0.98–2.78) | 0.060 |

| Quit | 1.04 (0.60–1.79) | 0.903 | 1.09 (0.60–1.98) | 0.775 | 1.25 (0.65–2.38) | 0.508 |

| Duration of Infertility (months, N = 891) | 0.99 (0.982–0.994) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.983–0.996) | 0.002 | 0.99 (0.982–0.996) | 0.003 |

| Total Motile Sperm (million, N = 900) | 1.00 (0.999–1.001) | 0.602 | 1.00 (0.999–1.001) | 0.863 | 1.00 (0.999–1.001) | 0.917 |

| Prior Conception (N = 900) | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.39 (1.06–1.83) | 0.017 | 1.42 (1.06–1.89) | 0.020 | 1.20 (0.89–1.63) | 0.235 |

| Prior Loss (N = 900) | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.48 (1.11–1.98) | 0.008 | 1.46 (1.07–1.98) | 0.016 | 1.25 (0.91–1.73) | 0.174 |

| Prior Parity (N = 900) | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.32 (0.95–1.84) | 0.096 | 1.30 (0.92–1.84) | 0.138 | 1.10 (0.76–1.59) | 0.612 |

| Prior Infertility Therapy (N = 900) | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.80 (0.61–1.05) | 0.106 | 0.78 (0.58–1.04) | 0.086 | 0.83 (0.61–1.13) | 0.236 |

| AMH (ng/mL, N = 874) | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 0.030 | 1.07 (0.999–1.15) | 0.053 | 1.08 (1.004–1.16) | 0.038 |

| Emotion domain score of FertQol | 0.996 (0.989–1.004) | 0.336 | 0.996(0.988–1.004) | 0.295 | 0.994(0.986–1.002) | 0.122 |

Conception was defined as having a rising serum level of human chorionic gonadotropin for two consecutive tests; pregnancy was defined as an intrauterine pregnancy with fetal heart motion, as determined by transvaginal ultrasonography; live birth was defined as the delivery of a viable infant.

88 cm is the cutoff value of abdominal obesity according to World Health Organization instructions (see reference).

Multivariable Analyses

Adjusted odds ratios for the predictors of pregnancy outcomes of conception, clinical pregnancy, and live-birth are presented in Table 2. In addition to treatment group effects, age, waist circumference (categorical), income, duration of infertility, and history of a prior pregnancy loss were associated with one or more of the pregnancy outcomes (Table 2). Race, education status, psychosocial stress as assessed by the emotional domain of the FertiQol survey, and serum level of AMH were not significantly associated with any pregnancy outcome in this adjusted analysis. Income of ≥$50,000 was associated with a 1.66 and 2.02 greater odds of conception and live-birth, respectively. A waist circumference >88 cm remained associated with an increased odds of conception, but not pregnancy or live-birth. A history of prior loss remained significantly associated with increased odds for all pregnancy outcomes (Table 2). No significant interactions (p <.05) were found between treatment group and any other selected significant predictors (data not shown). Table 2 contains the OR and 95% CI only for those variables that were selected in the models for conception, clinical pregnancy, and live-birth. Adjusted ORs for all predictors (including those not selected for the models for conception, pregnancy, and live-birth) are presented in Supplemental Table 2. Additionally, a full list of those predictors which were and were not associated with the outcome of live birth is presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for predictors in the final model for conception, pregnancy, and live birth for AMIGOS subjects. All variables were included in the stepwise model. Age and treatment group survived the final model. No significant interactions (p <.05) were found between treatment group (as a whole) and any other predictors included in this table.

| Variables | Conception^ OR (95% CL) |

P-value | Pregnancy# OR (95% CL) |

P-value | Live Birth$ OR (95% CL) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Group | ||||||

| Letrozole | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Clomiphene | 1.43 (1.00, 2.04) | 0.050 | 1.36 (0.93, 1.98) | 0.111 | 1.30 (0.87, 1.95) | 0.197 |

| Gonadotropin | 2.46 (1.73, 3.51) | <.001 | 1.99 (1.38, 2.88) | <.001 | 2.20 (1.49, 3.24) | <.001 |

| Age | 0.96 (0.92, 0.99) | 0.011 | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) | 0.005 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.97) | <.001 |

| Waist Circumference (cm)* | ||||||

| <=88 | 1 | |||||

| >88 | 1.54 (1.15, 2.06) | 0.004 | ||||

| Income | ||||||

| <$50,000 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >=$50,000 | 1.66 (1.10, 2.49) | 0.015 | 2.02 (1.24, 3.29) | 0.005 | ||

| Wish not to answer | 1.40 (0.85, 2.32) | 0.186 | 1.91 (1.07, 3.41) | 0.028 | ||

| Duration of Infertility (months) | 0.988 (0.982, 0.995) | <0.001 | 0.990 (0.983, 0.997) | 0.003 | 0.991 (0.984, 0.999) | 0.020 |

| Prior Loss (N = 900) | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.76 (1.29, 2.42) | <0.001 | 1.75 (1.26, 2.43) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.11, 2.23) | 0.010 |

When included as a continuous variable, waist circumference did not remain in the final model for conception.

For the final model, area under the curve (AUC)=0.66; p=0.27 for the Hosmer and Lemeshow (HL) goodness-of-fit test.

For the final model, AUC=0.64; p=0.47 for the HL goodness-of-fit test.

For the final model, AUC=0.65; p=0.99 for the HL goodness-of-fit test.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics associated and not associated with the outcome of live birth in the AMIGOS trial following multivariable adjustment

| Variables associated with live-birth | Variables not associated with live-birth |

|---|---|

| Treatment Group | BMI (female) |

| Age | BMI (male) |

| Income | Waist Circumference |

| Duration of Infertility | Waist Hip Ratio |

| Prior Loss | Ethnicity |

| Race | |

| Education | |

| Smoking | |

| Alcohol use | |

| Total Motile Sperm | |

| Prior Conception | |

| Prior Parity | |

| Prior Infertility Therapy | |

| AMH | |

| Emotion domain score of the FertiQol |

To assess the overall predictive value of the developed models for conception, clinical pregnancy and live birth, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated and area under the curves (AUC) were calculated (Figure 1). While the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (21) for goodness-of-fit of the final logistic regression models suggests a good fit of the models to the data (conception p = 0.27, pregnancy p = 0.47, and live-birth p = 0.99), the AUCs suggest a relatively poor predictive value of the models [conception AUC = 0.66 (95% CI: 0.63 – 0.70), pregnancy AUC = 0.64 (95% CI: 0.60 – 0.68), and live-birth AUC = 0.65 (95% CI: 0.61 – 0.69); Figure 1]. Although age alone as anticipated is a powerful predictor of outcomes, the addition of the other variables identified in the multivariable analysis meaningfully improved the predictive power of the models. The AUCs for conception, clinical pregnancy and live birth models excluding age are 0.65 (95% CI: 0.62 – 0.70), 0.62 (95% CI: 0.58 – 0.66), and 0.63 (95% CI: 0.59 – 0.67), respectively.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves and area under the curve (AUC) for the final models for conception, pregnancy, and live-birth

Compared to women who reported income ≥$ 50,000/year, women with reported income < $50,000/yr. had a greater median waist circumference (87 cm vs. 83 cm), were less likely to have a history of infertility therapy (45% vs. 58%) and had a longer duration of infertility (median 36 mos. vs. 24 mos.) all p < 0.05 or less, in spite of being slightly younger (31.5 vs. 32 years, p = 0.04). Women who did not answer this income question were similar to those whose reported income was <$50,000/yr. except for the baseline factors of duration of infertility, prior fertility therapy, and waist circumference, which were similar to women who reported income >$50,000/yr.

Conception rates were lower in the < $50,000/yr. group as compared to the ≥ $50,000/yr. group and in those who declined to answer this question. A significant part of the observed differences in live-birth rates across the income groups (Supplemental Table 1) was due to a higher rate of clinical pregnancy loss in women in the < $50,000/yr. group (28.6%) compared to those in the ≥ $50,000/yr. group (11.9%) and to those who declined to answer this question (10.6%, p = 0.026).

Discussion

Because of the large number of couples diagnosed with unexplained infertility, a better understanding of factors associated with outcomes is important in order to guide treatment options and to counsel patients effectively. Previously, the single center randomized Fast Track and Standard Treatment (FASTT) clinical trial aimed to determine the efficacy of OS-IUI in woman with unexplained infertility 21–39 years of age. However, the primary endpoints of this study were time to live-birth and cost-effectiveness of gonadotropin-IUI compared to IVF, and predictors of treatment success were not assessed (22). Given its large size, randomized multicenter nature, and comprehensive ascertainment of demographic and reproductive characteristics, the AMIGOS trial offered an important opportunity to investigate predictors of success for OS-IUI.

Important baseline characteristics that were significantly associated with one or more clinical outcomes here included age, waist circumference, income category, duration of infertility, and a history of prior pregnancy loss. Age as a significant predictor of outcomes is not surprising, as chronological age has previously been identified as a significant predictor of clinical pregnancy following OS-IUI treatments utilizing both gonadotropins and clomiphene citrate (23,24). While the magnitude of the OR may appear to reflect a small impact on clinical outcomes (0.93 for the outcome of live-birth), this effect is per year, and thus is quite meaningful over a several year interval. For example, using a < 31 year-old group as reference, the OR for live-birth for the >34 year-old group is 0.62(0.42–0.91).

Duration of infertility as a predictor of pregnancy outcomes following OS-IUI treatment has been reported in some (7,25) but not all investigations (24). The present investigation identified duration of infertility as associated with all three pregnancy-related outcomes including, importantly, live-births. Since the etiology of unexplained infertility is likely multifactorial, this finding is not unexpected. Specifically, those couples with a shorter duration of infertility are likely affected with fewer or less severe fertility factors than those with a longer duration, and therefore may be expected to have superior outcomes following treatment. Similarly, those couples with a prior pregnancy loss have shown that they can conceive, and thus could also be considered less subfertile than those with no prior pregnancy. Additionally, if the prior pregnancy loss was related to an identifiable factor, this may have been found and treated, thus resulting in an improved outcome in a subsequent pregnancy. To this end, our finding of an association between a prior pregnancy loss and improved pregnancy outcomes is not surprising.

The finding that a waist circumference of > 88 cm was associated with increased odds of conception, but not clinical pregnancy or live-birth, was unanticipated. Although BMI was not significantly associated with outcomes, women with a larger waist circumference may be a subgroup of obese women with subtle menstrual cycle abnormalities (26). It is possible that OS treatments are able to overcome these barriers to conception, but ultimately metabolic abnormalities may interfere with continued gestation resulting in lower subsequent clinical pregnancy and live birth rates. While increased insulin resistance was noted in the women with a waist circumference of > 88 cm, insulin resistance, per se, was not found to be associated with any of the pregnancy outcomes.

The finding that those reporting an annual income of <$50,000 had fewer conceptions and live-births with OS-IUI is an important finding and warrants further evaluation. Recently a large body of literature has identified disparities in outcomes following fertility treatments associated with socioeconomic factors, including income, education and race (29,30). Most of this literature has focused on outcomes following ART rather than less aggressive treatments such as OS-IUI. Interestingly, in a prior retrospective study, income, employment status, and ethnicity were each strongly associated with the likelihood of seeking infertility treatment (27). Women reporting an annual income of <$50,000 were more likely to have a longer duration of infertility and to not have previously undergone fertility treatments prior to entering into the AMIGOS trial. While the longer duration of infertility in the lower income group may suggest different underlying etiologies associated with the couples’ subfertility, it may also represent differences in access to care. Although the costs associated with fertility treatments associated with the AMIGOS trial were covered by the study, infertility evaluation and treatment prior to participation in the study was likely influenced by income. Since only one of the twelve clinical sites participating in the AMIGOS trial was in a state that mandated insurance coverage for comprehensive infertility treatment, direct comparison of outcomes between mandated and non-mandated sites was not possible. While economic factors may be an important reason why women in the <$50,000/yr. group had not previously pursued evaluation and treatment, other potential barriers include lack of appropriate information, lack of referrals from primary care physicians, and/or cultural differences in the pursuit of elective fertility therapy (28).

The observation of an increased pregnancy loss rate following the identification of a clinical pregnancy in the <$50,000/yr. group as compared to the ≥$50,000/yr. group is also concerning. While differences in obstetrical outcomes could be due to differences in the underlying characteristics of the populations, this potentially could also represent differences in the access to or the quality of obstetrical care received. In our bivariate analyses, black race was associated with significantly lower odds of live-birth; however, education level was not associated with any of the pregnancy outcomes. In the adjusted analysis both race and educational status were not significantly associated with pregnancy outcomes. Given that race and educational status, in addition to income, have been associated with outcomes following IVF treatments (29,30), these findings warrant further evaluation.

Social determinants of health such as low income, disparities in access to care, and minority status are considered stressors and have been related to poor outcomes of care both within and outside of the context of infertility (28–31). While many stressors are external, a growing body of literature suggests that modifiable factors such as cognitive attributes may be related to treatment outcomes (32–34). Since income <$50,000/yr. was associated with decreased odds of live-birth, we were interested in the relationship between psychological stress captured with the FertiQol emotional domain score in the AMIGOS trial and treatment outcomes. The FertiQol quality of life behavioral instrument is a validated tool designed to assess the burden of infertility in men and women experiencing infertility (17,18). While we did not identify significant associations between this score and the outcomes of treatment, self-reported stress has previously been reported to not be correlated with time to pregnancy (35). Physiological markers of stress such as salivary alpha-amylase have been associated with time to pregnancy (35,36) and may be a better marker of psychosocial stress. Unfortunately this marker was not obtained in the AMIGOS trial.

Importantly, the present investigation did not observe an association between modifiable lifestyle factors and the outcome of live-birth. Specifically, BMI, alcohol use, and smoking status were not found to be significantly associated with any pregnancy outcome in the bivariate or multivariate analyses. Given that these lifestyle factors are commonly assumed risks for poor treatment outcomes, these negative findings are of interest. While few investigations have addressed lifestyle factors in relation to OS-IUI treatment outcomes, each has similarly found no relationship between smoking and outcomes (10,37–38). Even less addressed has been the relationship between alcohol use and OS-IUI outcomes. Our prior investigation of a much smaller OS-IUI database (664 couples with unexplained infertility, 164 of whom underwent up to four cycles of OS-IUI) found a positive association with the outcome of live birth in former users of alcohol as compared to current and never users—a finding not replicated in the present study (10). The same investigation found that former use of coffee and tea was associated with greater pregnancy and live-birth rates as compared to never and current users (10). In the AMIGOS trial data reported here, coffee and tea use information was not collected so these relationships could not be assessed. Previous investigations have also failed to identify a relationship between BMI and pregnancy outcomes following OS-IUI treatments (10,39).

In adjusted analyses serum levels of AMH were also not significantly associated with any treatment outcomes. Although AMH levels have been associated with treatment outcomes in the setting of IVF, even after adjustment for the number of oocytes recovered, there is consensus that this marker is much more predictive of oocyte quantity than quality (40,41). As such, the lack of a significant relationship between serum levels of AMH and treatment outcome following OS-IUI, which must be considered less dependent on ovarian reserve than is IVF, is not surprising.

In addition to identifying baseline risk factors associated with treatment outcomes, a second goal of the present investigation was to develop models predictive of outcome following OS-IUI. Although the Hosmer–Lemeshow test suggests that the derived models for conception, pregnancy and live-birth are a good fit to the data, the AUCs for the models demonstrates their overall poor performance. The modest performance of the derived models is likely partially explained by the relatively few significant predictors incorporated into the models as well as the complex outcomes of pregnancy and live-birth in a population with unexplained infertility.

In summary, in this large prospective clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness and multiple pregnancy rates associated with OS-IUI treatments for unexplained infertility, baseline age, duration of infertility, a history of prior pregnancy loss, and income were significant predictors of pregnancy outcomes. While age and duration of infertility are expected to be related to outcomes including live-birth, the identification of income as a predictor independent of race and education was unanticipated. As seen in patients undergoing more time and cost intensive infertility treatments such as IVF, the findings of this study suggest that differences in access to elective fertility care as well as different underlying etiologies of infertility across income groups, may contribute significantly to treatment outcomes and should be further investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SUPPORT: The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Grants for AMIGOS: U10 HD39005, U10 HD38992, U10 HD27049, U10 HD38998, U10 HD055942, HD055944, U10 HD055936, U10HD055925, U10HD077680. This research was made possible by the funding by American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the 71st annual ASRM meeting, Baltimore MD, 2015

Clinical trial registration: NCT01044862

References

- 1.Stephen EH, Chandra A. Updated projections of infertility in the United States: 1995–2025. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(1):30–34. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downey J, Yingling S, McKinney M, Husami N, Jewelewicz R, Maidman J. Mood disorders, psychiatric symptoms, and distress in women presenting for infertility evaluation. Fertil Steril. 1989;52(3):425–432. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60912-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteford LM, Gonzalez L. Stigma: the hidden burden of infertility. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00124-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzick DS, Grefenstette I, Baffone K, Berga SL, Krasnow JS, Stovall DW, et al. Infertility evaluation in fertile women: a model for assessing the efficacy of infertility testing. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(12):2306–2310. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins JA, Corsignani PG. Unexplained infertility: a review of diagnosis, prognosis, treatment efficacy and management. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1992;39(4):267–275. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(92)90257-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClamrock HD, Jones HW, Jr, Adashi EY. Ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination at the quarter centennial: implications for the multiple births epidemic. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(4):802–809. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzick DS, Carson SA, Coutifaris C, Overstreet JW, Factor-Litvak P, Steinkampf MP, et al. Efficacy of superovulation and intrauterine insemination in the treatment of infertility. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(3):177–183. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond MP, Legro RS, Coutifaris C, Alvero R, Robinson RD, Casson P, et al. Letrozole, Gonadotropins, or Clomiphene Citrate for Unexplained Infertility. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(13):1230–1240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodson WC, Kunselman AR, Legro RS. Association of obesity with treatment outcomes in ovulatory infertile women undergoing superovulation and intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H, Hansen KR, Factor-Litvak P, Carson SA, Guzick DS, Santoro N, et al. Predictors of pregnancy and live birth after insemination in couples with unexplained or male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farhi J, Orvieto R. Influence of smoking on outcome of COH and IUI in subfertile couples. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:421–424. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9330-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis KM, Savitz DA, et al. Effects of cigarette smoking, caffeine consumption, and alcohol intake on fecundability. Am J Epdemiol. 1997;146:32–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson K, Nisenblat V, Norman R. Lifestyle factors in people seeking infertility treatment-a review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luke B, Brown MB, Stern JE, Missmer SA, Fujimoto VY, Leach R, et al. Female obesity adversely affects assisted reproductive technology (ART) pregnancy and live birth rates. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:245–252. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossi BV, Berry KF, Hornstein MD, Cramer DW, Ehrlich S, Missmer SA. Effect of alcohol consumption on in vitro fertilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):136–142. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820090e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond MP, Legro RS, Coutifaris C, Alvero R, Robinson RD, Casson P, et al. Assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial: baseline characteristics. Fertil Steril. 2015 Apr;103(4):962–973. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.12.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boivin J, Takefman J, Braverman A. The Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQoL) tool: development and general psychometric properties. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:409–415. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aarts JW, van Empel IW, Boivin J, Nelen WL, Kremer JA, Verhaak CM. Relationship between quality of life and distress in infertility: a validation study of the Dutch FertiQoL. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1112–1118. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. Waist circumference and waist– hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dólleman M, Verschuren WM, Eijkemans MJ, Dollé ME, Jansen EH, Broekmans FJ, van der Schouw YT. Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-Müllerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013 May;98(5):2106–2115. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. A goodness-of-fit test for the multiple logistic regression model. Commun Stat. 1980;A10:1043–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reindollar RH, Regan MM, Neumann PJ, Levine BS, Thornton KL, Alper MM, Goldman MB. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate optimal treatment for unexplained infertility: The fast track and standard treatment (FASTT) trial. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(3):888–899. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brzechffa PR, Daneshmand S, Buyalos RP. Sequential clomiphene citrate and human menopausal gonadotropin with intrauterine insemination: the effect of patient age on clinical outcome. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(8):2110–2114. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.8.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merviel P, Heraud MH, Grenier N, Lourdel E, Sanguinet P, Copin H. Predictive factors for pregnancy after intrauterine insemination (IUI): an analysis of 1038 cycles and a review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nuojua-Huttunen S, Tomas C, Bloigu R, Tuomivaara L, Martikainen H. Intrauterine insemination treatment in subfertility: an analysis of factors affecting outcome. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:698–703. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.3.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain A, Polotsky AJ, Rochester D, Berga SL, Loucks T, Zeitlian G, et al. Pulsatile luteinizing hormone amplitude and progesterone metabolite excretion are reduced in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2468–2473. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler LM, Craig BM, Plosker SM, Reed DR, Quinn GP. Infertility evaluation and treatment among women in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(4):1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain T. Socioeconomic and racial disparities among infertility patients seeking care. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(4):876–881. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellons MF, Fujimoto VY, Baker VL, Barrington DS, Broomfield D, Catherino WH, et al. Race matters: a systematic review of racial/ethnic disparity in Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology reported outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(2):406–409. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahalingaiah S, Berry KF, Hornstein MD, Cramer DW, Missmer SA. Does a woman's educational attainment influence in vitro fertilization outcomes? Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2618–2620. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marmot M. The health gap: the challenge of an unequal world. Lancet. 2015 Sep 9; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00150-6. pii: S0140-6736(15)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domar A, Gordon K, Garcia-Velasco J, La Marca A, Barriere P, Beligotti F. Understanding the perceptions of and emotional barriers to infertility treatment: a survey in four European countries. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(4):1073–1079. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berga SL, Marcus MD, Loucks TL, Hlastala S, Ringham R, Krohn MA. Recovery of ovarian activity in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea who were treated with cognitive behavior therapy. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(4):976–981. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)01124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michopoulos V, Mancini F, Loucks TL, Berga SL. Neuroendocrine recovery initiated by cognitive behavioral therapy in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(7):2084–2091. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch CD, Sundaram R, Buck Louis GM, Lum KJ, Pyper C. Are increased levels of self-reported psychosocial stress, anxiety, and depression associated with fecundity? Fertil Steril. 2012;98:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynch CD, Sundaram R, Maisog JM, Sweeney AM, Buck Louis GM. Preconception stress increases the risk of infertility: results from a couple-based prospective cohort study—the LIFE study. Hum. Reprod. 2014;29(5):1067–1075. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farhi J, Orvieto R. Influence of smoking on outcome of COH and IUI in subfertile couples. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:421–424. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9330-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merviel P, Heraud MH, Grenier N, Lourdel E, Sanquinet P, Copin H. Predictive factors for pregnancy after intrauterine insemination (IUI): an analysis of 1038 cycles and a review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodson WC, Kunselman AR, Legro RS. Association of obesity with treatment outcomes in ovulatory infertile women undergoing superovulation and intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodin T, Hadziosmanovic N, Berglund L, Olovsson M, Holte J. Antimüllerian Hormone Levels Are Strongly Associated With Live-Birth Rates After Assisted Reproduction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1107–1114. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Radi D, Argento C, Baraldi E, Artenisio AC, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART) Hum Reprod Update. 2010 Mar-Apr;16(2):113–130. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.