Abstract

Study Design

Electrophysiological recordings were obtained from proprioceptors in deep lumbar paraspinal muscles of anesthetized cats during high velocity low amplitude spinal manipulation (HVLA-SM).

Objective

To determine how thrust direction of an HVLA-SM affects neural input from back musculature.

Summary of Background Data

A clinician's ability to apply the thrust of an HVLA-SM in a specified direction is considered an important component of its optimal delivery. However, previous biomechanical studies indicate that the shear force component of the thrust vector is not actually transmitted to paraspinal tissues deep to the thoracolumbar fascia because the skin-fascia interface is frictionless.

Methods

Neural activity from muscle spindles in the multifidus and longissimus muscles were recorded from L6 dorsal rootlets in 18 anesthetized cats. Following preload to the spinal tissues, HVLA-SMs (100ms thrust duration) were applied through the intact skin overlying the L6 lamina. Thrusts were applied with at angles oriented perpendicularly to the back and obliquely at 15° and 30° medialward or cranialward using a 6×6 Latin square design with 3 replicates. The normal force component was kept constant at 21.3N. HVLA-SMs were preceded and followed by simulated spinal movement applied to the L6 vertebra. Changes in mean instantaneous discharge frequency (ΔMIF) of muscle spindles were determined during the thrust and during spinal movement.

Results

ΔMIFs during the HVLA-SM were significantly greater in response to all thrust directions compared to the preload alone but there was no difference in ΔMIF for any of the thrust directions during the HVLA-SM. HVLA-SM decreased some of the responses to simulated spinal movement but thrust direction had no effect on these changes.

Conclusions

The shear force component of an HVLA-SM's thrust vector is not transmitted to the underlying vertebra sufficient to activate muscle spindles of the attached muscles. Implications for clinical practice and clinical research are discussed.

Keywords: spinal manipulation, spinal manipulative therapy, dosage, muscle spindles, neurophysiology, multifidus muscle, spine, cat, thrust vector, thrust direction

Introduction

Well over 40 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and a substantial number of systematic reviews have evaluated the efficacy of spinal manipulation for low back pain (e.g., see1,2). Sufficient benefits have been reported enabling clinical guidelines and evidence reports to support the use of spinal manipulation in the management of low back pain.3-5 In everyday life, patients often use spinal manipulation when seeking care for low back pain.6-8 Utilization data indicate most patients treated with spinal manipulation (SM) receive a high velocity low amplitude procedure (HVLA-SM).6,9,10

HVLA-SM is a biomechanical treatment whose application can be identified by several physical characteristics including its preload, its duration, amplitude, direction and site of application.11 We currently know very little regarding the relationship between any of these physical parameters and an HVLA-SM's capacity to either evoke or optimize a successful clinical outcome. To our knowledge in efficacy studies of spinal manipulation, biomechanical characterization of the treatment procedure actually delivered to study participants has rarely if ever been identified.12 This lack of detailed knowledge about the treatment variable in manipulation RCTs stands in striking contrast to the well-defined and consistently applied dosages used in efficacy studies for drug treatment. Consequently, scientific efforts to accurately assess the efficacy of spinal manipulation may be confounded by either not controlling for or by not having identified the physical characteristics of the treatments actually applied.

In studies using healthy individuals and animal models, several groups have begun to systematically investigate the relationship between the physical characteristics of an HVLA-SM and consequent physiological and biomechanical responses. These groups have standardized delivery of the HVLA-SM by developing devices to control its application.13-15 Their results demonstrate that the magnitude of the preload that precedes the manipulative thrust, the duration and amplitude of the thrust itself, and the specific contact site where the thrust is applied influence HVLA-SM-induced changes in EMG responses,16-18 spinal stiffness,19,20 and proprioceptive signaling.21-23 While the relationship between these changes and clinical outcomes is not known, the results collectively warrant the consideration that the occurrence and magnitude of clinical benefits from spinal manipulation could depend upon the physical characteristics of the HVLA-SM treatment being delivered.

In the current study we add to this body of knowledge by investigating the relationship between the direction in which the thrust of an HVLA-SM is applied and proprioceptive signaling from paraspinal muscle spindles. The appropriate application angle of an HVLA-SM is thought to impart the most vertebral displacement for the least amount of manipulative force.24 We identified muscle spindles as an outcome measure because neural input from co-activated paraspinal sensory receptors including muscle spindles during an HVLA-SM have long been thought to contribute to HVLA-SM's therapeutic effects.25-34 Using a feline model we tested the hypothesis that the magnitude of neural discharge from lumbar paraspinal muscle spindles during and following a simulated HVLA-SM depends upon thrust direction.

Methods

Experiments were performed on 18 deeply anesthetized cats weighing between 3.9 and 5.3kg [mean 4.4 (SD 0.4)]. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A mechanical device (Fig. 1) was used to apply simulated HVLA-SMs to the lumbar spine of deeply anesthetized cats while recording sensory activity from individual muscle spindles in lumbar muscles attached to the L6 vertebra (cats have 7 lumbar vertebrae). All surgical and electrophysiological procedures as well as the mechanical device have been previously described in detail.22,35-37 They are presented briefly in the Appendix along with a general description of the approach for delivering an HVLA-SM.

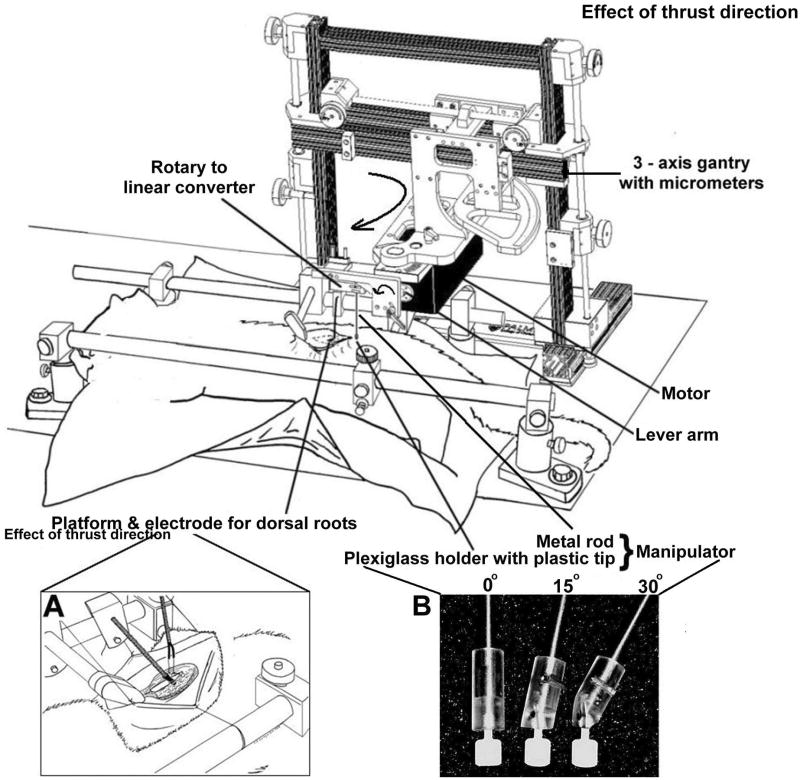

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the experimental set up. Inset A: cartoon of laminectomy, placement of recording electrode and platform for teasing dorsal rootlets. Inset B. Photograph showing distal end of manipulator terminating in tips that ensured similar contact areas with the skin during thrusts given perpendicular (0°), 15° and 30° to horizontal plane of the cat.

HVLA-SM characteristics

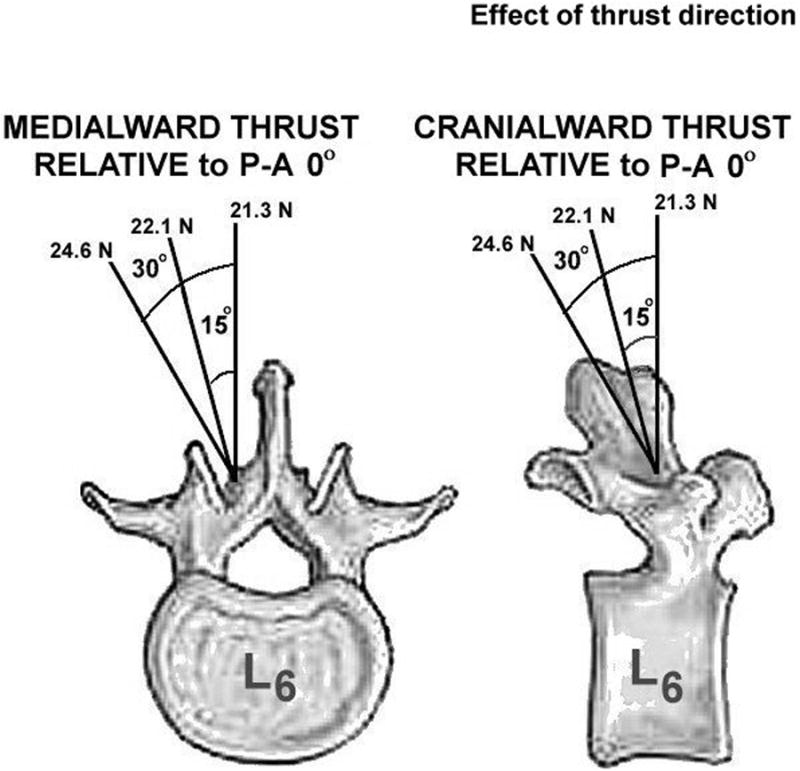

Five HVLA-SM thrust directions were studied: directly posterior-to-anterior (P-A 0°), combined P-A and angled medialward 15° or 30° and cranialward 15° or 30° (Fig. 2). To ensure similar contact areas between the manipulator and the skin overlying the L6 lamina, a plastic tip (Fig 1, inset B) was inserted into the appropriate plexiglass holder machined at an angle complementing the 0°, 15°, 30° thrust directions. Thrust duration was 100ms similar to that used clinically.38-40 Peak thrust force was 21.3N representing 55% of the average body weight of a cat and a scaled value used clinically.21,41 No data were available regarding whether clinicians change thrust amplitude when they modify their thrust direction. Consequently, we chose to keep the normal component of peak thrust force (perpendicular to the back of the cat) constant (21.3N) and allowed the orthogonal shear component (parallel to the back of the cat) to vary. Figure 2 shows the peak thrust force to which the motor was programmed based upon decomposition of each application angle. The applied shear forces were 5.7N for the two 15° HVLA-SMs and 12.3N for the two 30° HVLA-SMs (not depicted in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Drawing showing 5 thrust directions applied over the lamina of the L6 vertebra. The vertically-oriented, posterior to anterior peak thrust force was constant (21.3N) for each of the 5 thrust directions. Vector decomposition (21.3N / cos θ) required that the applied peak force be greater for the 15° and 30° thrust directions, yielding applied shear forces of 5.7N and 12N, respectively.

Ramp and hold challenge before and after the HVLA-SM

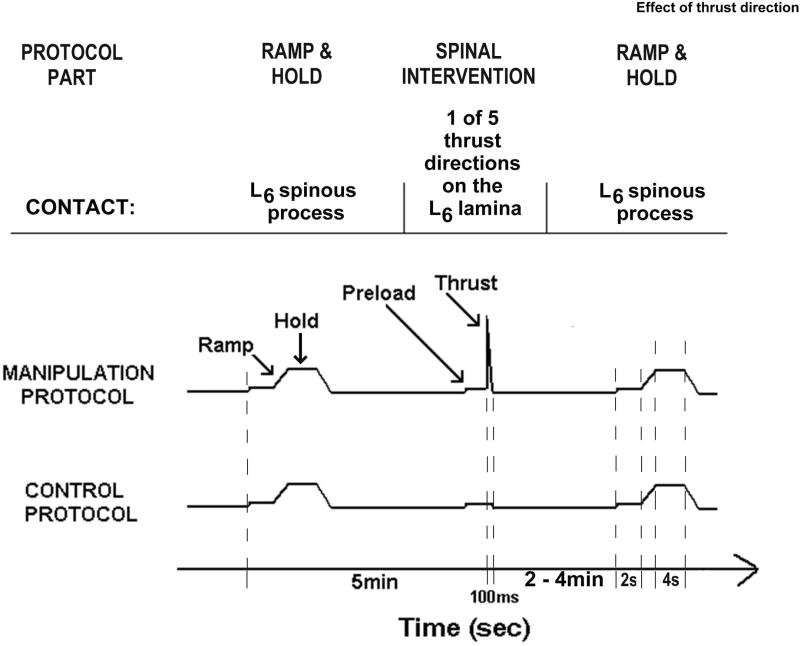

In addition to determining the effect of thrust direction on muscle spindle signaling during the HVLA-SM, we also determined the effect of thrust direction on muscle spindle signaling to spinal movement using methods previously reported19,20 (See Appendix for description). Figure 3 shows the ramp and hold stimuli which were applied at the L6 spinous process in a P-A direction before and after the HVLA-SM.

Figure 3.

Schematic showing the timeline and experimental protocols. Timeline is not drawn to scale.

Experimental design and protocols

Six experimental protocols were performed [1 control (preload only) and 5 manipulations (preload + thrust)]. As shown in Figure 3, each protocol consisted of three parts: 1) ramp and hold; 2) followed 5min later by a spinal intervention consisting of either preload alone or a preload and an HVLA-SM; 3) followed by a 2nd ramp and hold. Eighteen afferents were studied using a 6×6 Latin square design with 3 replicates. Each replicate began with the control protocol, followed by P-A 0°, cranialward 15°, cranialward 30°, medialward 15°, and medialward 30° HVLA-SM protocols. The first protocol was presented last during each succeeding cycle of the replicate.

Data analysis

Analysis was performed on changes in the muscle spindles' mean instantaneous discharge frequency both during the HVLA-SM relative to baseline (ΔMIFduring) and before and after the HVLA-SM to static or positional (ΔMIFresting, ΔMIFnew position) and to dynamic (ΔMIFaverage movement, and ΔMIFpeak movement) components of simulated spinal movement. See Appendix for detailed description of these outcome responses.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were fit with terms for replicate, blocking factor within replicate, order and protocol. Data analysis was performed using SAS System for Windows v9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC. Five pre-planned contrasts comparing each of the 5 thrust directions to preload only (control) were made to determine which of the ΔMIFs were different. Pre-planned contrasts were tested at the 0.05 level of significance. We then compared between those thrust directions that were significantly different from control, controlling for multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni method. Descriptive statistics are reported as means and standard deviations (SD). Inferential statistics are reported as means and 95% confidence intervals (lower, upper 95% CI) based on the ANOVA model.

Sample size calculations were obtained by estimating standard deviations during HVLA-SM from a previous study41 that compared 4 contact sites and which used a peak thrust amplitude and a thrust duration identical to those used in the current study. That study was also a Latin square design, so we were able to estimate standard deviations controlling for replicates and blocking factor within replicate. At the moment we have insufficient knowledge to know whether a threshold change in discharge exists that is clinically relevant. A previous study in a reduced cat preparation showed that a 50imp/s increase in the stimulation frequency of group Ia, muscle spindle afferents, from 50 to 100imp/s, most often decreased synaptic efficacy in α-motoneurons by more than 45% (see fig. 6 in ref42). To detect mean differences of at least 50imp/s in ΔMIFduring, our sample of 18 cats yielded 99% power for comparing between control and each HVLA-SM thrust direction and 90% power for comparing between each of the thrust directions and adjusting for the 10 pairwise multiple comparisons. In addition, previous studies in the cat showed that the static sensitivity of lumbar paraspinal muscle spindles is 16.2(imp/s)/mm of vertebral translation or 5.2(imp/s)/degree of vertebral rotation43 and that their velocity sensitivity at peak movement is 2.9(imp/s)/(mm/s).44 A change in spindle discharge of 5imp/s could alter the sensory signal signifying a vertebra's position by ∼0.3mm or 1° and the signal signifying its velocity of movement by ∼2mm/s. To detect mean differences of at least 5imp/s in ΔMIFrest, ΔMIFnew postion, and ΔMIFaverage movement, our sample of 18 cats yielded >99% power for comparing between control and each HVLA-SM thrust direction and >99% power for comparing between each of the thrust directions and adjusting for the possibility of 10 pairwise multiple comparisons. For ΔMIFpeak movement, our sample of 18 cats yielded 77% power to detect differences between control and each HVLA-SM thrust direction and 45% power to detect differences of at least 5imp/s between each of HVLA-SM thrust directions.

Results

Recordings were obtained from 18 single afferents belonging to muscle spindles in the lumbar paraspinal muscles (see Appendix for neurophysiological methods used to identify muscle spindle activity). All afferents increased their mean discharge frequency to succinylcholine injection. Mean maximum frequency increased by 78.8imp/s (19.3 to 201.2imp/s) and lasted at least two minutes. All spindles showed a sustained response to a fast vibratory stimulus of ∼65Hz. All afferents were silenced by muscle twitch (stimulation amplitude = 0.2 − 0.3mA; duration = 50μs). The most sensitive portion of each afferent's receptive field, suggestive of the spindle's location within the parent muscle, was often located (11/18 afferents) nearest the level where the L6 paraspinal muscles crossed over the L6-7 facet joint. For the remaining 7 afferents, 3 receptive fields were nearest to the L6 spinous process, 3 nearest to the L7 spinous process and 1 was nearest to the L5-6 facet joint.

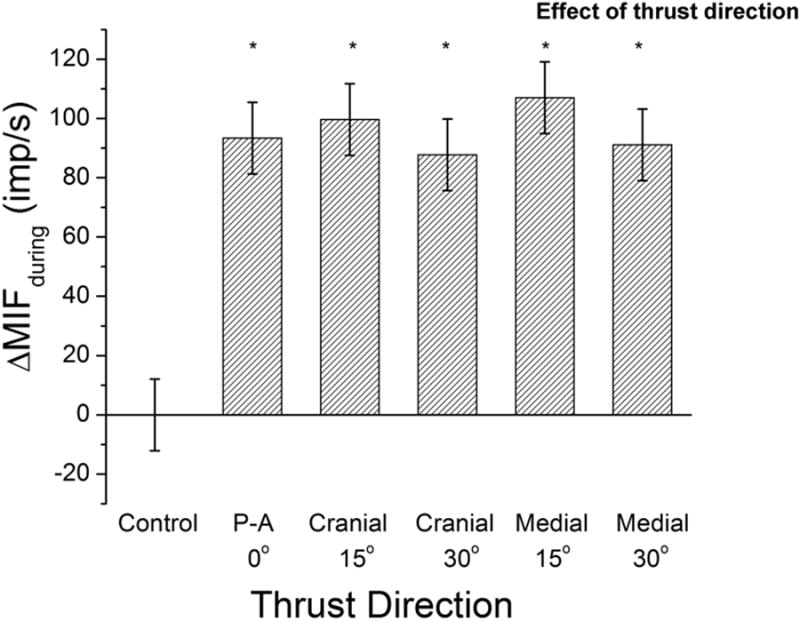

Effect of thrust direction on muscle spindle responses during the HVLA-SM

All five thrust directions significantly (p<0.001) increased ΔMIFduring compared to the preload alone (Fig. 4). The P-A 0° thrust increased ΔMIFduring 93.4(81.3, 105.5)imp/s; mean(lower, upper 95%CI)], the cranialward 15° thrust increased ΔMIFduring 99.7(87.6, 111.8)imp/s, the cranialward 30° thrust increased ΔMIFduring 87.7(75.6, 99.8)imp/s, the medialward 15° thrust increased ΔMIFduring 107.0(94.9, 119.1)imp/s, and the medialward 30° thrust increased ΔMIFduring 91.1(79.0, 103.2)imp/s. After controlling for multiple comparisons, ΔMIFduring was not significantly different between any of the 5 thrust directions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of 6 spinal interventions [1 preload control and 5 thrust directions for a high velocity low amplitude spinal manipulation with preload (HVLA-SM)] on muscle spindle discharge during the HVLA-SM. Column bars and error bars represent means and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. * p<0.001 relative to control. See Data Analysis section the Methods for description of ΔMIFduring.

Effect of thrust direction on muscle spindle responses to vertebral position following the HVLA-SM

Only the P-A 0° thrust direction significantly (p=0.02) decreased ΔMIFresting compared to control [2.6 (0.4, 4.8)imp/s] (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of 6 spinal interventions [1 preload control and 5 thrust directions for a high velocity low amplitude spinal manipulation with preload (HVLA-SM)] on changes in paraspinal muscle spindle responsiveness to the L6 vertebra's resting position following the HVLA-SM Column bars and error bars represent means and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. ‡ p=0.02 relative to control. See Data Analysis section the Methods for description of ΔMIFrest.

The medialward 15° and cranialward 30° thrust directions significantly (p=0.03) decreased ΔMIFnew position compared to control [2.8 (0.3, 5.2) and 2.7 (0.3, 5.2)imp/s]. ΔMIFnew position was not significantly different between the two thrust directions (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of 6 spinal interventions [1 preload control and 5 thrust directions for a high velocity low amplitude spinal manipulation with preload (HVLA-SM)] on changes in paraspinal muscle spindle responsiveness with the L6 vertebra placed in a new position. ¥ p=0.03 relative to control. See Data Analysis section the Methods for description of ΔMIFnew position.

Effect of thrust direction on muscle spindle responses to vertebral movement following the HVLA-SM

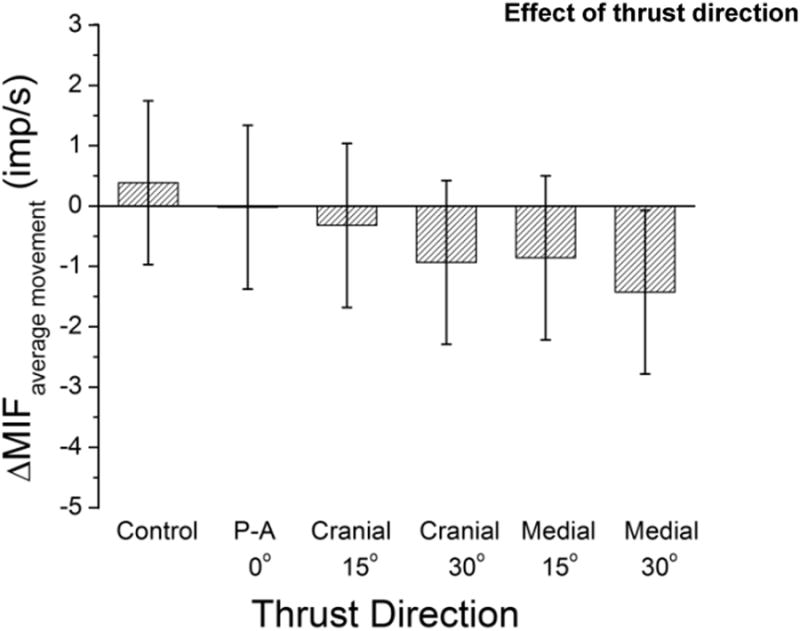

ΔMIFaverage movement was not significantly different from control for any of the 5 thrust directions (Fig 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of 6 spinal interventions [1 preload control and 5 thrust directions for a high velocity low amplitude spinal manipulation with preload (HVLA-SM)] on changes in paraspinal muscle spindle responsiveness to vertebral movement. See Data Analysis section the Methods for description of ΔMIFaverage movement.

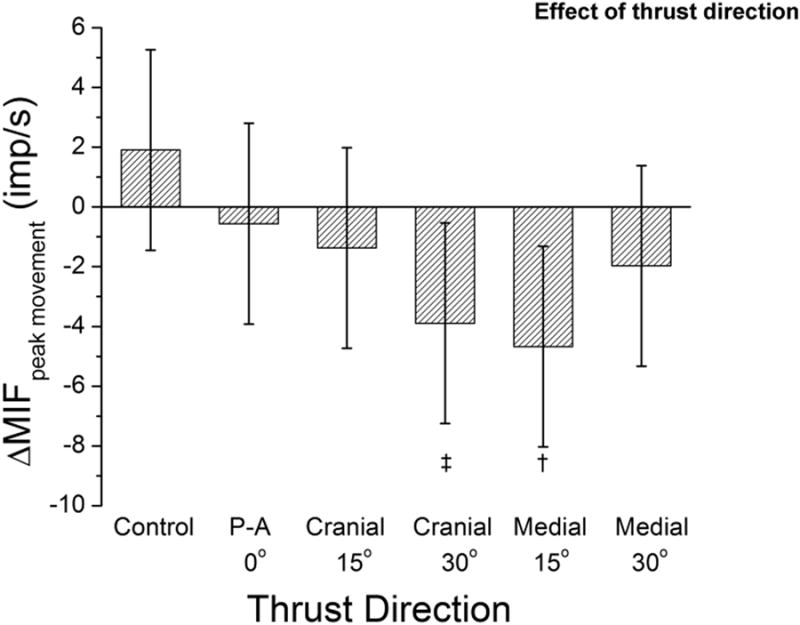

The medialward 15° and cranialward 30° thrust directions significantly (p=0.01, and p=0.02, respectively) decreased ΔMIFpeak movement compared to control [6.6(1.8, 11.3) and 5.8(1.0, 10.6) imp/s]. ΔMIFpeak movement was not significantly different between the two thrust directions (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Effect of 6 spinal interventions [1 preload control and 5 thrust directions for a high velocity low amplitude spinal manipulation with preload (HVLA-SM)] on changes in paraspinal muscle spindle responsiveness at the greatest magnitude of vertebral movement. † p=0.01. See Data Analysis section the Methods for description of ΔMIFpeak movement.

Discussion

The data show that mean muscle spindle activity during the HVLA-SM is significantly greater in response to the HVLA-SM than to the preload alone confirming original findings of Wheeler and Pickar.13 The data extend these findings by showing that the increase in spindle discharge during the HVLA-SM is independent of thrust direction when the magnitude of the normal force component of the thrust vector remains constant. The data also confirm findings from a number of previous studies21,22,41 that HVLA-SM produces small and variable changes in muscle spindle responsiveness to vertebral position and movement. They extend these findings by showing that despite the medial 15° and cranial 30° HVLA-SMs decreasing spindle responsiveness to both a new vertebral position and the peak of vertebral movement, thrust direction has no effect on these decreases when the normal force component remains constant.

Across professions that use spinal manipulation (including chiropractic24, medicine45, osteopathy32, and physical therapy46), a clinician's ability to apply a manipulative thrust in a specified direction is considered an important component of its correct delivery. The desired thrust direction is most often described as being parallel to either the plane of the intervertebral disc or the facet joint space. This is thought to move the vertebra in a specified direction while providing the least resistance to its movement and limiting force transmission to the desired targets.11,24,40 Textbooks of manipulative technique describe the use of purely vertically-oriented posterior-to-anterior thrust vectors as well as obliquely-oriented thrust vectors that are angled lateral-to-medial or inferior-to-superior depending upon the region of the spine being manipulated. Obliquely-oriented thrust vectors introduce force components perpendicular (normal component) and parallel (shear component) to the contact's tangent plane. While the concept of spinal manipulation being able to return a vertebra to a specified position is antiquated to many,25 current thinking emphasizes the restoration of zygapophyseal joint mobility and joint play.25,47 HVLA-SM does alter vertebral position at least temporarily, as indicated by the presence of increased facet joint spacing after a side posture HVLA-SM.48

Two biomechanical studies call into question whether the shear force component of an obliquely-oriented thrust vector can be transmitted to the underlying vertebra so as to actually move the vertebra in the thrust direction. In human participants Bereznick et al.49 studied the relationship between perpendicular and parallel forces applied independently at a contact point with the kyphosis of the thoracic spine using a plexiglass plate. They concluded that the fascial interface between the thoracic skin and deeper tissues is frictionless making the shear component incapable of transmitting force to the underlying deeper tissues. To further address the issue, they studied movement of the thoracic skin when contact was made using methods similar to those used in clinical practice which are thought to hook onto or stabilize against a spinous or transverse process. They found that when a shear force is applied, slippage still occurs. They did not however apply a preload to tauten the skin against the spinous or transverse process as is performed in clinical practice. The potential for the shear component to transmit force to the deeper tissues may have been overestimated. In a second kinematic study using porcine lumbar spines, Kawchuk and Perle50 investigated the effect of thrust angle on accelerations of the target vertebra. They concluded that unlike a perpendicular thrust (normal force component only) obliquely-oriented thrusts do not increase vertebral accelerations in the thrust direction, which was also in agreement with their pre-test estimates of decreased force with increasing application angle.

Our neurophysiological data using muscle spindles to assess the transmission of force and movement to deep tissues in the lumbar spine of the cat supports the above conclusions and extends Bereznick et al.'s observations to the lumbar spine. Muscle spindles are activated when muscle is stretched because spindles lie parallel to the extrafusal fibers. Physiologically this happens when a joint is moved and muscle stretches as its attachments move away from each other. Transverse forces applied directly over a muscle belly can also activate the spindles51 introducing the possibility that, in the current study, spindle responses resulted simply from transverse forces distributed from the manipulator's tip, through the skin, to the underlying paraspinal muscles. That transverse stimulation was not the case has been shown in a previous study using the same animal preparation.41 In that study, contact sites over a vertebra distant to the muscle spindle's receptive field were just as effective at increasing spindle discharge as contact sites close to the receptive field. In the present study, with the thrust force's normal component kept constant but its shear component increasing, muscle spindle responses during the manipulation and the responsiveness of muscle spindles to movement following the manipulation each remained similar. Consistent with this finding, the effects of muscle history on muscle spindle responses are the same regardless of whether the thoracolumbar fascia is present or not.52 Thus, even if there were friction at the skin-thoracolumbar fascia interface, this fascia does not appear to transmit shear loads to paraspinal muscle spindles.

Historically, HVLA-SM's mechanism of action is thought to arise from biomechanical and neurophysiological processes.25,27,32 During the manipulation, the optimally applied HVLA-SM may remove impediments to normal spinal motion by reducing intraarticular adhesions, freeing trapped intraarticular meniscoids, or removing distortions of the annulus fibrosus.53-55 In addition, sensory nerve endings in paraspinal tissues, including muscle spindles,34,56 are thought to be stimulated to magnitudes or in patterns that alter central neural processing in ways that are physiologically beneficial.29,33,57-59 spinal motion could produce persistent changes in the inflow of sensory information with beneficial effects on somatosensory integration and well-being.

One limitation of the current study is that it could not determine whether activation of muscle spindles contributes to HVLA-SM's mechanism of action. Contributions from this proprioceptor still remain theoretical.34,56 In addition, the current study did not determine whether neural activity decreases when the thrust application angle increases and the total applied thrust force remains constant. A third limitation is that the study may have been underpowered to find 5imp/s differences in the peak dynamic changes to vertebral movement (ΔMIFpeak movement) during the ramp and hold challenge.

The findings from the present study combined with results from Bereznick, Kawchuk and Perle49,50 have implications for clinical practice and clinical research. If a clinician's goal is to deliver an HVLA-SM with a certain linear force, anticipating that it will set in motion either a biomechanical or neurophysiological mechanism, one needs to recognize that transmitted linear forces and vertebral displacements will decrease as their thrust angle becomes more oblique. The magnitude of their thrust vector needs to increase concomitant with increasing thrust angle. If delivering an HVLA-SM parallel to either the plane of the intervertebral disc or the facet joint space does provide the least resistance to vertebral movement and helps limit force transmission to desired targets11,24,40 these studies suggest that the clinician's approach for accomplishing this would be positioning both the patient and self in way that the plane of the intervertebral disc or joint space is as perpendicular as possible to the plane of the thrust's contact area.

Descriptions of the HVLA-SM used in clinical studies typically lack adequate detail to determine how the treatment's physical characteristics relate to clinical outcomes.60 The need for phase II-type, pre-clinical trials to help identify the effective components of manual therapies has been recognized.61 The findings described in this paper indicate that knowing the magnitude of the thrust force normal to the plane of the thrust's contact area is important for characterizing the amplitude of an HVLA-SM because only this component appears to be transmitted neurophysiologically and biomechanically. Training clinicians to achieve targeted thrust force levels appears achievable.62,63 This study adds to a growing list of preclinical investigations to identify the biomechanical characteristics of an HVLA-SM that affect neural,21-23 biomechanical19,20 and physiological responses.16-18

Acknowledgments

NIH grants U19 AAT004137 and K01 AT005935 funds were received in support of this work. No relevant financial activities outside the submitted work.

Appendix

Surgical and electrophysiological procedures

Briefly, deep anesthesia was maintained with Nembutal [35mg/kg intravenous]. A laminectomy was performed at L5 exposing the L6 dorsal rootlets for electrophysiological recordings (cats have 7 lumbar vertebrae). Tissues attaching to and overlying the L6 and L7 vertebrae remained intact including the skin. Finely teased filaments from the L6 dorsal rootlets were placed on a monopolar electrode (Fig. 1, inset A) until single unit activity was identified that increased only in response to mechanical pressure applied directly to the lumbar multifidus or longissimus muscles and not to pelvic or leg muscles.

Neurophysiological techniques to identify muscle spindle activity

One afferent was investigated per cat because following completion of all spinal manipulations, surgical exposure of the intact spinal tissues was needed to confirm that afferent activity was from muscle spindles in the lumbar region. To confirm that the afferent innervated a muscle spindle 1) intra-arterial succinylcholine injection (100–400mg/kg) was used to increase discharge by loading the spindles during intrafusal fiber contraction, 2) direct bipolar muscle stimulation was used to decrease discharge by unloading the spindles during extrafusal fiber contraction, and 3) a fast vibratory stimulus was used to increase discharge as previously described.22 Spindle responses represented their passive activity because deep anesthesia and cutting the dorsal roots abolished reflex gamma responses. Single unit action potentials were passed through a high impedance probe (HIP511, Grass, MA), amplified (P511K, Grass, MA), and then recorded and analyzed using a PC based data acquisition system (Spike2, v7, Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, England).

Mechanical device and delivery of an HVLA-SM

Figure 1 shows the mechanical device used to apply an HVLA-SM, identical to that used in previous investigations.22,37 The motor was controlled by a programmable, electronic feedback system. Rotary motion of the motor's lever arm was converted to linear motion using a custom built converter. The converter in turn was attached to a manipulator consisting of a metal rod terminating in a plexiglass holder for a small, circular,(5mm diameter) plastic tip (Fig. 1 inset B). The angle of the rod relative to the spine was controlled by rotating the motor in the horizontal plane (Fig 1, large curved arrow) and rotating the rotary to linear converter in the vertical plane (Fig. 1, small curved arrow).

Spinal manipulation simulated an HVLA-SM delivered in a posterior-anterior direction to the low back of a prone patient. Contact was made on the skin over the lamina of L6. A lamina contact was chosen for two reasons. This contact site is commonly used in clinical practice.64 Second, in a previous study a lamina contact evoked the largest average increase in spindle discharge.41 Locating the lamina was standardized relative to the L6 spinous process based upon the average of measurements from 3 cadaveric cat spines. The L6 lamina was 3mm lateral and 7mm caudal to the L6 spinous process. The L6 spinous process was identified by palpation and the plastic tip positioned using the micrometers attached to each axis of the 3-axis gantry.

Each HVLA-SM was preceded by an identical preload applied directly posterior to anterior. Because the thrust is intended to impart movement to a vertebra8 we applied a preload force of a magnitude at which the L6 vertebra began to move using methods previously described.19,22,23 Preload force was determined for each cat.

Ramp and hold challenge before and after the HVLA-SM

The motor was programmed to deliver a ramp and hold displacement (see waveform in Fig. 3) to the L6 vertebra starting from its baseline, preloaded resting position. The ramp consisted of slowly (0.5mm/s) moving the L6 vertebra ventralward over 4s. The hold consisted of maintaining the vertebra at the new position for 4s. The second ramp shown in Figure 3 was delivered as quickly as possible (2-4min) following the thrust, first requiring replacing the plexiglass holder and plastic tip with a 0° plexiglass holder machined to cradle the spinous process and prevent slippage, and then requiring moving the motor into position over the L6 spinous process. The 2nd ramp occurred 120s following the P-A-directed HVLA-SM, 125-130s following each of the cranialward-directed HVLA-SMs, and 240-245s following each of the medialward-directed HVLA-SMs.

Data Analysis

All neural discharge was first quantified as instantaneous frequency (IF). The response during the spinal intervention portion of both the manipulation and control protocols was obtained by subtracting the mean IF (MIF) of the 2s baseline prior to the thrust from the MIF of the last 87.5ms of the 100ms thrust interval, yielding the response measure ΔMIFduring. The first 12.5ms was omitted in order to exclude the brief burst of activity that occurs at the start of movement associated with acceleration.65,66

For the ramp and hold, spindle responses to position were represented by MIF measured over the 2s baseline prior to the onset of the ramp i.e., the vertebra's resting position (MIFresting), and by MIF measured during the last 2s of the hold when the vertebra was placed in a new position (MIFnew position). By calculating MIFnew position over the last 2s of the 4s-hold mechanical contributions from the effects of tissue creep and spindle receptor adaptation were minimized.66 Spindle responses to movement were represented by the average IF calculated over the time-course of the entire ramp (MIFaverage movement) and by taking the average of the 3 largest IFs during the last half of the ramp (MIFpeak movement). Changes in spindle responsiveness due to the spinal intervention were then determined by subtracting each MIF that followed the spinal intervention from its respective MIF before the intervention, yielding four response measures to spinal movement: ΔMIFresting, ΔMIFnew position, ΔMIFaverage movement, and ΔMIFpeak movement.

Footnotes

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

Level of Evidence: N/A

References

- 1.Goertz C, Pohlman KA, Vining RD, et al. Patient-centered outcomes of high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulation for low back pain: a systematic review. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22:670–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubinstein SM, Terwee CB, Assendelft WJ, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low back pain: an update of the cochrane review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:E158–E177. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827dd89d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koes BW, Van TM, Lin CW, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2075–94. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans RL, et al. Efficacy of spinal manipulation and mobilization for low back pain and neck pain: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Spine J. 2004;4:335–56. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shekelle PG, Adams AH, Chassin MR, et al. Spinal manipulation for low-back pain. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:590–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-7-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, et al. Characteristics of visits to licensed acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:463–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, et al. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survery. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen MG, Kerkhoff D, Kollasch MW, Cohn L. Job Analysis of Chiropractic. Greeley, CO: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergmann TF. High-velocity low-amplitude manipulative techniques. In: Haldeman S, Dagenais S, Budgell B, et al., editors. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. 3rd. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 755–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas M, Groupp E, Panzer D, et al. Efficacy of cervical endplay assessment as an indicator for spinal manipulation. Spine. 2003;28:1091–6. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000067276.16209.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickar JG, Wheeler JD. Response of muscle proprioceptors to spinal manipulative-like loads in the anesthetized cat. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:2–11. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.112017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Descarreaux M, Nougarou F, Dugas C. Standardization of spinal manipulation therapy in humans: development of a novel device designed to measure dose-response. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaillant M, Pickar JG, Kawchuk GN. Performance and reliability of a variable rate, force/displacement application system. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:585–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nougarou F, Dugas C, Deslauriers C, et al. Physiological responses to spinal manipulation therapy: investigation of the relationship between electromyographic responses and peak force. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36:557–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page I, Nougarou F, Dugas C, et al. The effect of spinal manipulation impulse duration on spine neuromechanical responses. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2014;58:141–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francois N, Claude D, Loranger M, et al. The role of preload forces in spinal manipulation: experimental investigation of kinematic and electromyographic responses in healthy adults. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37:287–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaillant M, Edgecombe T, Long CR, et al. The effect of duration and amplitude of spinal manipulative therapy on the spinal stiffness. Man Ther. 2012;17:577–83. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edgecombe TL, Kawchuk GN, Long CR, et al. The effect of application site of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) on spinal stiffness. Spine J. 2013;15:1332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed WR, Long CR, Kawchuk GN, et al. Neural responses to the mechanical parameters of a high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulation: effect of preload parameters. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed WR, Cao DY, Long CR, et al. Relationship between biomechanical characteristics of spinal manipulation and neural responses in an animal model: effect of linear control of thrust displacement versus force, thrust amplitude, thrust duration, and thrust rate. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:492039. doi: 10.1155/2013/492039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao DY, Reed WR, Long CR, et al. Effects of thrust amplitude and duration of high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulation on lumbar muscle spindle responses to vertebral position and movement. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson DH. Principles of Adjustive Technique. In: Bergmann TF, Peterson DH, Lawrence DJ, editors. Chiropractic Technique. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 123–96. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach RA. The Chiropractic Theories. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Price DD, et al. The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain: A comprehensive model. Man Ther. 2009;14:531–8. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickar JG. Neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002;2:357–71. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(02)00400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korr IM. The Neurobiologic Mechanisms in Manipulative Therapy. New York: Plenum Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillette RG. A speculative argument for the coactivation of diverse somatic receptor populations by forceful chiropractic adjustments. Manual Med. 1987;3:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haldeman S. Spinal manipulative therapy; a status report. Clin Orthop. 1983;179:62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henderson CNR. Three neurophysiologic theories on the chiropractic subluxation. In: Gatterman MI, editor. Foundations of chiropractic: Subluxation. 2. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. pp. 296–303. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenman PE. Principles of Manual Medicine. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickar JG, Bolton PS. Spinal manipulative therapy and somatosensory activation. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korr IM. Proprioceptors and somatic dysfunction. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1975;74:638–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pickar JG. An in vivo preparation for investigating neural responses to controlled loading ofa lumbar vertebra in the anesthetized cat. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;89:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sung PS, Kang YM, Pickar JG. Effect of spinal manipulation duration on low threshold mechanoreceptors in lumbar paraspinal muscles: a preliminary report. Spine. 2005;30:115–22. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000147800.88242.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed WR, Pickar JG. Paraspinal muscle spindle response to intervertebral fixation and segmental thrust level during spinal manipulation in an animal model. Spine. 2015;40:E752–E759. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hessell BW, Herzog W, Conway PJW, et al. Experimental measurement of the force exerted during spinal manipulation using the Thompson technique. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1990;13:448–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herzog W, Conway PJ, Kawchuk GN, et al. Forces exerted during spinal manipulative therapy. Spine. 1993;18:1206–12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Triano JJ. Biomechanics of spinal manipulative therapy. Spine J. 2001;1:121–30. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(01)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed WR, Long CR, Kawchuk GN, et al. Neural responses to the mechanical characteristics of high velocity, low amplitude spinal manipulation: Effect of specific contact site. Man Ther. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luscher HR, Ruenzel PW, Henneman E. Effects of impulse frequency, PTP, and temperature on responses elicited in large populations of motononeurons by impulses in single Ia-fibers. J Neurophysiol. 1983;50:1045–58. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.5.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao DY, Pickar JG, Ge W, et al. Position sensitivity of feline paraspinal muscle spindles to vertebral movement in the lumbar spine. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1722–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.90976.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao DY, Khalsa PS, Pickar JG. Dynamic responsiveness of lumbar paraspinal muscle spindles during vertebral movement in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 2009;197:369–77. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isaacs ER, Bookhout MR. Bourdillon's Spinal Manipulation. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edmond SL. Manipulation and Mobilization. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewit K. Manipulative Therapy in Rehabilitation of the Locomotor System. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cramer GD, Cambron J, Cantu JA, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging zygapophyseal joint space changes (gapping) in low back pain patients following spinal manipulation and side-posture positioning: a randomized controlled mechanisms trial with blinding. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36:203–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bereznick DE, Ross JK, McGill SM. The frictional properties at the thoracic skin-fascia interface: implications in spine manipulation. Clin Biomech. 2002;17:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawchuk GN, Perle SM. The relation between the application angle of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and resultant vertebral accelerations in an in situ porcine model. Man Ther. 2009;14:480–3. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bridgman CF, Eldred E. Hypothesis for a pressure-sensitive mechanism in muscle spindles. Science. 1964;143:481–2. doi: 10.1126/science.143.3605.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao DY, Pickar JG. Thoracolumbar fascia does not influence proprioceptive signaling from lumbar paraspinal muscle spindles in the cat. J Anat. 2009;215:417–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farfan HF. The scientific basis of manipulation procedures. In: Buchanan WW, Kahn MF, Laine V, et al., editors. Clinics in rheumatic diseases. London: W.B. Saunders Company Ltd.; 1980. pp. 159–77. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giles LGF. Anatomical Basis of Low Back Pain. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haldeman S. The clinical basis for discussion of mechanisms of manipulative therapy. In: Korr IM, editor. The neurobiologic mechanisms in manipulative therapy. NY: Plenum; 1978. pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clark BC, Goss DA, Jr, Walkowski S, et al. Neurophysiologic effects of spinal manipulation in patients with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ianuzzi A, Khalsa PS. High loading rate during spinal manipulation produces unique facet joint capsule strain patterns compared with axial rotations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:673–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pickar JG, Kang YM. Paraspinal muscle spindle responses to the duration of a spinal manipulation under force control. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bialosky JE, Simon CB, Bishop MD, et al. Basis for spinal manipulative therapy: A physical therapist perspective. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22:643–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Downie AS, Vemulpad S, Bull PW. Quantifying the high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulative thrust: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:542–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller J, Gross A, D'Sylva J, et al. Manual therapy and exercise for neck pain: A systematic review. Man Ther. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Triano JJ, Giuliano D, Kanga I, et al. Consistency and Malleability of Manipulation Performance in Experienced Clinicians: A Pre-Post Experimental Design. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(6):407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gudavalli MR, Vining RD, Salsbury SA, et al. Clinician proficiency in delivering manual treatment for neck pain within specified force ranges. Spine J. 2015;15:570–6. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson DH, Bergmann TF. The spine: anatomy, biomechanics, assessment, and adjustive techniques. In: Bergmann TF, Peterson DH, Lawrence DJ, editors. Chiropractic Technique. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 197–522. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hunt CC, Ottoson D. Initial burst of primary endings of isolated mammalian muscle spindles. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:324–30. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matthews PBC. Mammalian muscle receptors and their central actions. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkin Co.; 1972. [Google Scholar]