Abstract

3-Nitrobenzanthrone (3-NBA), an environmental mutagen found in diesel exhaust and a suspected carcinogen, undergoes metabolic reduction followed by reaction with DNA to form aminobenzanthrone (ABA) adducts, with the major alkylation product being N-(2′-deoxyguanosin-8-yl)-3-aminobenzanthrone (C8-dG-ABA). Site-specific synthesis of the C8-dG-ABA adduct in the oligodeoxynucleotide 5'-d(GTGCXTGTTTGT)-3':5'-d(ACAAACACGCAC)-3'; X = C8-dG-ABA adduct, including codons 272-275 of the p53 gene, has allowed for investigation into the structural and thermodynamic properties of this adduct. The conformation of the C8-dG-ABA adduct was determined using NMR spectroscopy and was refined using molecular dynamics (MD) calculations restrained by experimentally determined interproton distance restraints obtained from NOE experiments. The refined structure revealed that the C8-dG-ABA adduct formed a base-displaced intercalated conformation. The adducted guanine was shifted into the syn conformation about the glycosidic bond. The 5'- and 3'-neighboring base pairs remained intact. While this facilitated π-stacking interactions between the ABA moiety and neighboring bases, the thermal melting temperature (Tm) of the adduct-containing duplex showed a decrease of 11 °C as compared to the corresponding unmodified oligodeoxynucleotide duplex. Overall, in this sequence, the base-displaced intercalated conformation of the C8-dG-ABA lesion bears similarity to structures of other arylamine C8-dG adducts. However, in this sequence, the base-displaced intercalated conformation for the C8-dG-ABA adduct differs from the conformation of the N2-dG-ABA adduct reported by de los Santos and co-workers, which oriented in the minor groove towards the 5' end of the duplex, with the modified guanine remaining in the anti conformation about the glyosidic torsion angle, and the complementary base remaining within the duplex. The results are discussed in relationship to differences between the C8-dG-ABA and N2-dG-ABA adducts with respect to susceptibility to nucleotide excision repair (NER).

Introduction

The nitroarene 3-nitrobenzanthrone (3-NBA, 3-nitro-7H-benz[de]anthracen-7-one) (Chart 1), a byproduct of incomplete combustion,1, 2 is found in diesel exhaust2-5 and as an environmental contaminant.1, 6 It has one of the highest reported levels of mutagenesis in the Ames assay.7 3-NBA is approximately three orders of magnitude more mutagenic than the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P)8, 9 or the most abundant nitroarene found in diesel exhaust, 1-nitropyrene10 (1-NP). 3-NBA causes DNA damage11-14 and has exhibited mutagenicity in mammalian cells as well.13-18 It produces micronuclei in human B-lymphoblastoid cells,19 human hepatoma cell lines,20 and mouse peripheral blood reticulocytes.21 Furthermore, cells exposed to 3-NBA possess increased levels of reactive oxygen species.22 Human exposure to 3-NBA has been documented through identification of metabolites in urine.23 These and other findings have led the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) to classify 3-NBA as a class 2B (possibly carcinogenic to humans) chemical and whole diesel exhaust as a class 1 compound (carcinogenic to humans).24

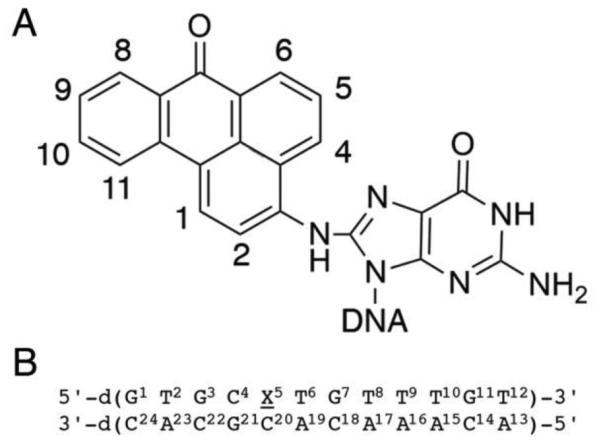

Chart 1.

A. Chemical structure of the C8-dG-ABA adduct including numbering scheme of the adduct protons for NMR. B. The oligodeoxynucleotide sequence used in this work, showing numbering of the individual nucleotides.

3-NBA undergoes enzymatic nitroreduction to 3-aminobenzanthrone (3-ABA) in vivo.23, 25 Activated intermediates of this conversion include the nitrenium ion, the proximate mutagenic species. This ion exists as a hybrid of two resonance structures, which can alkylate DNA at either the exocyclic nitrogen or the C2-position of the benzanthrone ring (Chart 2).5, 21, 26-32 Three DNA adducts have been identified. The major alkylation product, N-(deoxyguanosin-8-yl)-3-aminobenzanthrone (C8-dG-ABA), forms at the C8 position of guanine. In addition, alkylation may occur at the N2-dG position and the N6-dA position, to form 2-(deoxyguanosin-N2-yl)-3-aminobenzanthrone (N2-dG-ABA) and 2-(deoxyadenosin-N6–yl)-3-aminobenzanthrone (N6-dA-ABA), respectively (Chart 3).14, 33-35

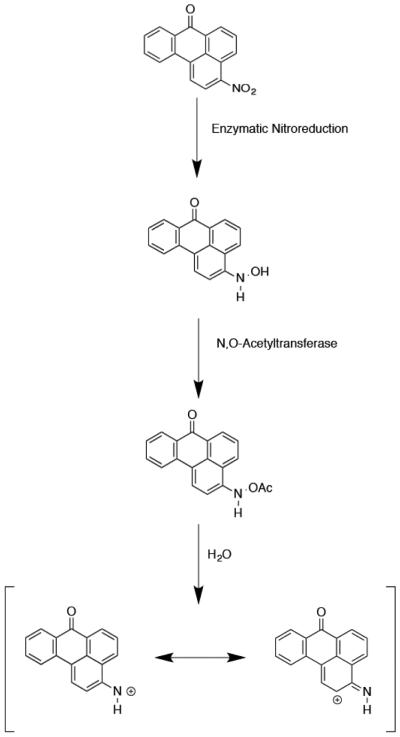

Chart 2.

Activation of 3-NBA into reactive electrophiles. Phase I activation occurs through nitroreduction. Phase II activation can occur through acetylation or sulfonation of the hydroxyl group (acetylation shown). Final activation occurs through solvolysis to form a nitrenium ion.

Chart 3.

Reaction of the electrophilic nitrenium ion of 3-NBA with DNA to form three DNA aminobenzanthrone adducts. These occur at the C8 position of guanine, or the N2 position of guanine and the N6 position of adenine to produce the three adducts shown.

The three adducts are repaired with differing efficiencies by the nucleotide excision repair (NER) proteins.14 In cultured human cells, the N2-dG-ABA adduct is the least efficiently repaired while the C8-dG-ABA and N6-dA-ABA adducts are repaired with approximately 3.5 and 4.5 times greater efficiencies, respectively.14 If not repaired, each of these three adducts blocks replicative DNA polymerases but is bypassed to different degrees by Y-family polymerases during translesion synthesis (TLS).14, 36 The C8-dG-ABA adduct presents the most significant block to TLS, allowing only 17% bypass, as compared to 33% for the N2-dG-ABA adduct and 43% for the N6-dA-ABA adduct after a 72 h incubation period.14 Bypass of these adducts during TLS is mutagenic.14, 18, 37 Depending on the type of assay, both G to T transversions36 and G to A transitions14 have been reported as the primary mutations in mammalian cells. The types of cells, the DNA sequence context, and whether the adducts are situated in a normal duplex or a bubble region are factors thought to modulate the mutagenic spectra of these adducts.36

The conformations of the N2-dG-ABA, C8-dG-ABA, and N6-dA-ABA adducts have been of interest; it has been anticipated that differences in their conformations and thermodynamic properties in DNA might correlate with differences in their biological processing, both with respect to DNA repair and translesion replication. Lukin et al.38 reported the site-specific synthesis of the N2-dG-ABA adduct and reported its conformation in an oligodeoxynucleotide duplex. They showed that the 3-ABA moiety resided in the minor groove and was oriented toward the 5´-end of the modified strand. Of note, the N2-dG-ABA adduct increased the thermal melting temperature (Tm) of the duplex, which, in principle, is consistent with its slower repair and its persistence in vivo.14 The observation that the C8-dG-ABA adduct is repaired with greater efficiency by NER14 suggested that it might instead decrease the Tm of an oligodeoxynucleotide duplex. Indeed, like other bulky C8-dG arylamine adducts, such as those formed by aminopyrene (AP),39 N-acetyl-aminofluorene (AAF),40 aminofluorene (AF),41 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo [4,5-b] pyridine (PhIP),42 and 2-amino-3-methylimidazo [4,5-f] quinoline (IQ),43 it seemed conceivable that the C8-dG-ABA adduct might be oriented in either a base-displaced intercalated or minor groove external conformation in this sequence context. Previous reports indicated that these bulky C8-dG adducts tended to adopt one of these conformations when placed in sequence between two pyrimidine nucleotides.38

We report here our findings for the three-dimensional structure and conformation of the C8-dG-ABA adduct in DNA. We examined conformational perturbations induced by this DNA adduct in the dodecamer 5'-d(GTGCXTGTTTGT)-3':5'-d(ACAAACACGCAC)-3'; X = C8-dG-ABA adduct. This sequence includes codons 272-275 of p53 gene, in which 3-NBA-induced G to T mutations have been reported.44 We employed NMR spectroscopy to elucidate the effect of the C8-dG-ABA adduct on the conformation of this duplex. We also employed UV/vis spectroscopy to investigate its effect on the duplex melting temperature (Tm). We show that in this sequence context the C8-dG-ABA adduct forms a base-displaced intercalated conformation.

Materials and Methods

Sample Synthesis and Characterization

The synthesis and purification of the C8-dG-ABA modified oligodeoxynucleotide 5´-d(GTGCXTGTTTGT)-3´, X = C8-dG-ABA, was performed as reported.18 The unmodified single strand oligodeoxynucleotides 5´-d(GTGCGTGTTTGT)-3´ and 5´-d(ACAACACGCAC)-3´ were obtained from the Midland Certified Reagent Co. (Midland, TX). Their purity was verified with capillary gel electrophoresis and reverse-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Gemini C-18 250 × 10 mm column) utilizing a gradient of acetonitrile in a mobile phase containing 0.1 M ammonium formate (pH 7). In all cases, following a 5 min equilibration period with 5% acetonitrile, a gradient from 5% to 16% acetonitrile was employed over 30 min. The flow rate was 2.0 mL min−1. Samples were purified by HPLC under the same conditions. The samples were deemed to be ≥ 99% pure following this procedure. Purified oligomers were desalted by passing over G-25 Sephadex. They were dried by evaporation using a centrivap apparatus (Labconco, Kansas City, MO). Oligodeoxynucleotide concentrations were determined by absorbance spectroscopy measurements at 260 nm. The calculated extinction coefficients45 were 1.09 × 105 L mol−1 cm−1 for the modified strand and 1.21 × 105 L mol−1 cm−1 for the complementary strand. The calculated extinction coefficient of the modified strand was not corrected for the presence of the ABA adduct. The modified or unmodified oligodeoxynucleotides were each annealed with the complementary strand in 10 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, and 50 μM Na2EDTA (pH 7). The samples were heated to 85 °C for 10 min and then cooled to room temperature to form either the unmodified DNA duplex or the duplex containing the C8-dG-ABA adduct. To establish the precise 1:1 strand stoichiometry, the duplex samples were subjected to DNA grade hydroxyapatite chromatography.46 A gradient from 10 mM to 100 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7) over 120 min was employed. The final strand stoichiometry was verified both by capillary gel electrophoresis and HPLC chromatography.

Mass Spectrometry

Single strand oligodeoxynucleotides were characterized using a Voyager MALDI-TOF spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY). A matrix consisting of 3-hydroxypicolinic acid in ammonium hydrogen citrate was used. Mass spectra were recorded in the negative ion mode and recorded to ± 1 m/z. Mass spectrometry of the duplex containing the C8-dG-ABA adduct was performed using a SYNAPT LC-TOF mass spectrometer (Waters Corp, Milford, MA). UHPLC was performed using an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 2.1 × 50 mm column (Waters Corp) with a gradient from 5% to 15% acetonitrile in 0.1 M ammonium acetate (pH 7) over 15 min. The data collection window was set to observe masses between 300-2000 m/z in the negative ion mode.

DNA Melting Temperatures

Melting temperature determinations for the modified and unmodified duplexes were obtained using a Cary UV/vis spectrometer (Varian Associates, Palo Alto, CA). The sample absorbance was monitored at 260 nm. The sample concentrations were 2 μM in 10 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, and 50 μM Na2EDTA (pH 7). The thermal scan was performed from 5 °C to 85 °C in 1 °C min−1 increments. Tm values were determined using the first derivatives of the experimentally obtained absorbance vs. temperature plots.

NMR Spectroscopy

The duplexes were prepared in 10 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, and 50 μM Na2EDTA (pH 7), in volumes of 180 μL or 500 μL, utilized in either 3 mm or 5 mm NMR tubes, respectively. For experiments to examine non-labile protons samples were prepared in 99.996% D2O. Examination of labile protons was performed in 9:1 H2O:D2O. Water suppression was accomplished using the Watergate pulse program.47 All spectra were processed using the TOPSPIN software package (Bruker Biospin Inc., Billerica, MA) and further analyzed using TOPSPIN and SPARKY48 software. Spectra were referenced to the chemical shift of the water resonance at the corresponding temperature, with respect to trimethylsilyl propanoic acid (TSP).

Unmodified Duplex

Spectra were recorded at 1 mM concentration. NOESY49, 50 and COSY experiments in D2O were performed on a 900 MHz spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Inc., Billerica, MA) at 15 °C with 2048 real data points in the t2 dimension and 512 real data points in the t1 dimension. The NOESY spectrum was obtained using a mixing time of 250 ms. The NOESY and COSY spectra were zero-filled during processing to obtain final matrices of 2048 × 1024 data points.

C8-dG-ABA Duplex

NOESY and magnitude COSY spectra were obtained at 900 MHz at a sample concentration of 350 μM in 500 μL. The temperature was 25 °C. NOESY and COSY spectra were completed with 2048 real data points in the t2 dimension and 512 real data points in the t1 dimension. The NOESY spectra were obtained using mixing times of 80, 150, 200, and 250 ms. All spectra were zero-filled during processing to obtain final matrices of 2048 × 1024 data points. The NOESY spectra in 9:1 H2O:D2O were obtained on Bruker 800 MHz and Bruker 900 MHz spectrometers at 5 °C and 15 ºC respectively. The mixing time was 250 ms. The spectra were obtained with 2048 real data points in the t2 dimension and 512 real data points in the t1 dimension and then zero-filled during processing to obtain a matrix of 2048 × 1024 data points. Additional NOESY and magnitude COSY spectra were performed at 900 MHz at a concentration of 520 μM in 180 μL. The temperature was 15 °C. Other experimental conditions and spectra processing were the same as those used at 25 ºC.

NMR Distance Restraints

The program SPARKY48 was utilized to determine volume integrations of NOESY cross-peaks from 15 °C and 25 °C spectra with 250 ms mixing times. These integrations were also performed using 150 ms mixing time spectra. The intrinsic error of integrations was assigned as half of the volume of the lowest intensity cross-peaks. The confidence levels of the integrations were divided into five categories based on peak shape, peak intensity, degree of overlap, and proximity to the water resonance. A 10% error value was assigned to well-resolved and non-overlapping cross-peaks. Strong but slightly broadened or overlapped cross-peaks or peaks with moderate S/N were given a 20% error value. A 30% error value was assigned to strong but medially broadened or overlapped cross-peaks. Cross-peaks with weak S/N or slightly overlapped cross-peaks with moderate S/N were assigned a 40% error value. A 50% error value was assigned to cross-peaks near the diagonal or water suppression, highly broadened or overlapped cross-peaks, and cross-peaks with moderate S/N and medial overlap or broadening. Integration values of NOEs with assigned errors were used to generate distance restraints.51-53 Square potential energy wells corresponding to the upper and lower bounds of interproton distance vectors calculated by the program MARDIGRAS54 were utilized. Additional distance restraints were generated using Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding distances for base pairs, but excluding the X5:C20 base pair. Ten anti-distance restraints,55, 56 characterized by square potential energy wells maintaining inter-proton distances from a lower bound of 5 Å to an upper bound of 10 Å, were used.

Restrained Molecular Dynamics Calculations

Distance restraints, obtained as described above, were used in restrained molecular dynamics (rMD) calculations. Deoxyribose pseudorotation and phosphodiester backbone restraints derived from canonical B-DNA values were included in rMD calculations.57 Pseudorotation restraints were not included for bases C4, X5, T6, A19, and C20 as NMR data indicated perturbations for deoxyribose protons associated with these bases that may be associated with alternative deoxyribose puckers. Perturbations included changes in chemical shifts and/or peak volume integrations when compared to the unmodified duplex. Additionally, pseudorotation restraints were not included for terminal and penultimate nucleotides (T12, A13, C14, C24). The complete list of pseudorotation restraints that were utilized is provided in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. Backbone torsion angle restraints for nucleotides T2, G3, G7, T8, T9, T10, G11, C14, A15, A16, A17, C18, C22, and A23 were assigned potential energy well windows of ±30°. Nucleotides C4, T6, A19, and G21, which neighbored the X5:C20 base pair, were assigned potential energy well windows of ±60°. No backbone torsion angle restraints were used for the terminal and penultimate nucleotides G1, T12, A13, C24, the modified base X5, or its complementary base C20. The backbone torsion angle restraints were centered at the B-DNA backbone torsion angles α = -60º, β = 180º, γ = 60º, ε = 195º, and ζ = -105º. These were assigned potential energy wells as described above. The partial charges and bond lengths for the C8-dG-ABA adduct were calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G* basis set in the program GAUSSIAN,58 and are provided in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. The structure of the modified duplex used to initiate the rMD calculations was generated in PDB format using the program MOE.59 At the modified nucleotide X5 the C8-dG-ABA moiety was built manually and added to an unmodified duplex. The C8-dG-ABA moiety was manually positioned to intercalate in the duplex. The face of the ABA moiety containing the ABA H4, H5, H6 protons was positioned to face the minor groove and the bay area of the ABA moiety containing the H2, H1, H11, H10 protons was positioned to face the major groove. At nucleotide X5, the glycosidic bond was placed into the syn conformation. The complementary base C20 was displaced from the duplex into the major groove. The resulting structure was further modified using the program xLEaP60 to include values for partial charges and bond lengths of the ABA moiety as obtained from GAUSSIAN. The .top and .inp files were then generated in xLEaP for use in the program AMBER.61

The rMD calculations were performed using a simulated annealing protocol in the program AMBER61 using the parm99 force field.62 All restraints had applied force constants of 32 kcal mol −1 Å−2. The generalized Born model was used for solvation.63 The salt concentration was set at 0.1 M. Initial calculations were performed for 20 ps over 20,000 steps. The system was heated from 0 to 600 K for the first 1,000 steps with a 0.5 ps coupling. This was followed by 1,000 steps at 600 K then 16,000 steps of cooling to 100 K with 4 ps coupling. Cooling to 0 K was completed during the final 2,000 steps with 1 ps coupling. Final calculations were performed over 100,000 steps for 100 ps. The system was heated from 0 to 600 K for the first 5,000 steps with a 0.5 ps coupling. This was followed by 5,000 steps at 600 K then 80,000 steps of cooling to 100 K with 4 ps coupling. Cooling to 0 K was completed during the final 10,000 steps with 1 ps coupling. Structure coordinates were saved after each cycle. NOE generated distances were compared to intensities calculated from emergent structures using complete relaxation matrix analysis52 (CORMA). The ten structures with the lowest deviations from experimental distance restraints were used to generate an average refined structure. This structure was then subjected to energy minimization. A second set of calculations was completed in a similar manner without the use of the anti-distance restraints. These calculations were performed to check that the utilization of anti-distance restraints did not alter the course of the rMD calculations. For constant temperature rMD calculations, the X5 base was placed manually into the anti conformation about the glycosidic bond using the program.59 This structure was then energy minimized. All restraints used in the constant temperature rMD calculations remained the same as those used for the simulated annealing rMD calculations, as did the applied force constants of 32 kcal mol−1 Å−2. The emergent structures were evaluated as to sixth root residuals between the calculated NOE volumes and experimental NOE volumes53, 64 in the same manner as was calculated for the average refined structure emergent from the simulated annealing rMD calculations, using the program CORMA.

Data Deposition

The structure factors and coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank and Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (www.rcsb.org). The RCSB ID code for the duplex containing the C8-dG-ABA adduct is rcsb104415. The PDB ID code is 2n4m. The BMRB Id code is 25672.

Results

Characterization

Mass spectrometry of the single strand oligodeoxynucleotides confirmed the expected masses. The expected masses were 3941.5 g mol−1 for the modified strand, 3698.5 g mol−1 for the unmodified primary strand, and 3592.4 g mol−1 for the complementary strand, and the masses were recorded at 3942.1 g mol−1, 3697.4 g mol−1, and 3591.2 g mol−1, respectively.

DNA Melting Temperature

The melting temperature (Tm) for the C8-dG-ABA duplex was 44 °C. Compared to the measured melting point of 55 °C for the unmodified duplex, this represented a decrease in Tm of 11 °C.

NMR Spectroscopy

(a) DNA non-Exchangeable Protons

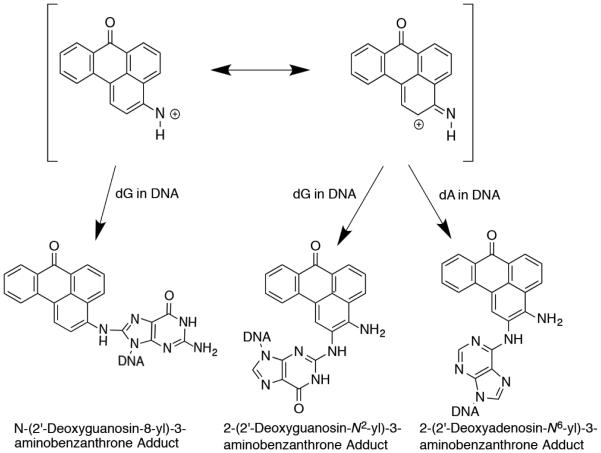

The base aromatic and deoxyribose anomeric protons were assigned using established procedures (Figure 1).65, 66 For the modified strand (Figure 1A), the modified base X5 is alkylated at the C8 position of the guanine imidazole ring, and hence, there is no X5 H8 proton. Consequently, the sequential pattern of NOE connectivity between the deoxyribose H1' protons and base aromatic protons was terminated. Additionally, the NOE between C4 H6 and C4 H1' was weak. The sequential pattern of NOE connectivity was re-initiated at the NOE between X5 H1' and T6 H6, which was also weak. The corresponding sequential pattern of NOE connectivity in the complementary strand (Figure 1B) was also interrupted. There was no NOE observed between A19 H8 and C20 H1'. The C18 H1' to A19 H8 NOE was weak. This indicated a perturbation in the complementary strand opposite the modified base X5. At 25 °C the T6 H6 resonance was overlapped with the G21 H8 resonance but at 15 ºC these two resonances could be resolved (Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). This allowed for the unequivocal identification of the NOEs associated with these two protons, including the NOE between X5 H1' and T6 H6. The adenine H2 protons were assigned based upon NOEs to the thymine imino protons of the respective A:T base pairs and cross-peaks to their respective H1´ protons. The remaining deoxyribose protons were assigned from a combination of NOESY and COSY data. The assignments of the non-exchangeable DNA protons for the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex and the corresponding unmodified duplex are summarized in Tables S2 and S3 of the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

Expanded plot of a NOESY spectrum of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex, showing the sequential NOE connectivity between aromatic H8/H6 protons and deoxyribose H1' protons. A. The modified strand, showing bases G1 through T12. The NOE connectivity is broken at the C4 H1´-H6 cross peak and reinitiates at the X5 H1’ - T6 H6 cross peak since the modified X5 base does not have an H8 proton. B. The complementary strand connectivity showing assignments for bases A13 through C24. The connectivity is broken at the A19 H1´→A19 H8 NOE and reinitiates at the C20 H1´→C20 H6 NOE; no NOE cross peak is observed between A19 H1´ and C20 H6. The 900 MHz spectrum was acquired at 25 ºC using a 250 ms mixing time.

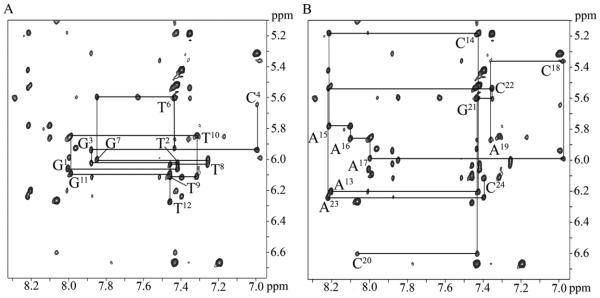

(b) DNA Exchangeable Protons

The imino and amino proton resonance regions of the NOESY spectrum are shown in Figure 2. The imino proton resonances were identified for all base pairs except for the terminal base pairs G1:C24 and T12:A13, and modified base pair X5:C20. The inability to assign the imino proton resonances of the terminal base pairs was attributed to their rapid exchange with water; two broad and unassignable resonances were observed in the imino proton region of the spectrum between 12.6 and 12.9 ppm, which may correspond to the imino protons of the terminal G1:C24 and T12:A13 base pairs. The anticipated NOEs between guanine N1H imino and cytosine N4H amino protons were observed for each of the remaining C:G base pairs. The anticipated NOEs between thymine N3H imino and adenine H2 protons were observed for each of the A:T base pairs, with the exception of the terminal base pair T12:A13. The T6 N3H imino resonance was broad, and its NOE to A19 H2 was weak as compared to the other NOEs between thymine N3H imino protons and adenine H2 protons. The chemical shift assignments for the exchangeable DNA protons of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex are provided in Table S3 of the Supporting Information with corresponding chemical shifts for the unmodified duplex shown in Table S4 of the Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

Expanded plots of the imino and amino regions of a NOESY spectrum of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex. Left Panel: The imino proton region of the spectrum, showing NOEs between guanine N1H and thymine N3H imino protons. The broadening of the T6 N3H imino proton resonance is evident, Right Panel: NOEs between the guanine N1H and cytosine N4H amino protons and between thymine N3H and adenine H2 protons. The NOEs are assigned as follows: a1, G21 N1H → C4 N4Hb; a2, G21 N1H → C4 N4Ha; b1, G7 N1H → C18 N4Hb; b2, G7 N1H → C18 N4Ha; c1, G3 N1H → C22 N4Hb; c2, G3 N1H →C22 N4Ha; d1, G11 N1H → C14 N4Hb; d2, G11 N1H → C14 N4Ha; e1, T6 N3H → A19 H2; f1, T2 N3H → A23 H2; g1, T8 N3H → A17 H2; h1, T10 N3H → A15 H2; i1, T9 N3H → A16 H2. Note that cross-peak e1, arising from base pair T6:A19, the 3'-neighbor with respect to the modified base pair X5:C20, is weaker than the cross peaks f1, g1, h1, and i1. The 900 MHz spectrum was acquired at 15 ºC using a 250 ms mixing time.

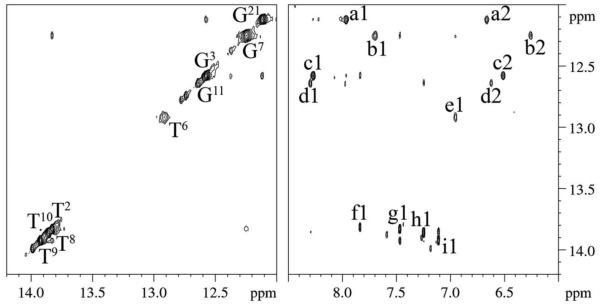

(c) Adduct Protons

The ABA moiety of the C8-dG-ABA adduct exhibits three distinct 1H spin systems, consisting of the H1 and H2 protons, the H4, H5, and H6 protons, and the H8, H9, H10, and H11 protons (Chart 1). The COSY spectrum was consistent with the presence of these three spin systems (Figure 3). Six COSY cross peaks were identified. The chemical shifts at 15 ºC of the ABA H1 and H2 proton resonances were identified at 8.04 ppm and 8.25 ppm on the basis of a strong COSY cross-peak. The ABA H4, H5, and H6 resonances were identified in the COSY spectrum at 7.95 ppm, 7.61 ppm, and 8.26 ppm, respectively. Strong scalar couplings were observed between the adjacent protons H4 and H5, and H5 and H6; a weaker scalar coupling was observed between H4 and H6. A comparison of NOESY and COSY data allowed for identification of the ABA H8, H9, H10, and H11 protons. In the NOESY data an NOE was observed between the H1 proton and the H11 proton, allowing H11 to be assigned at 7.78 ppm. With this assignment in hand, H8, H9, H10 could be assigned from the COSY spectrum, at 7.42 ppm, 6.64 ppm, 7.20 ppm, respectively. The assignments of the ABA H4 and H6 resonances were corroborated by NOEs between H4 and H6 and deoxyribose protons of the modified base as shown in Figure 4. The assignments of the C8-dG-ABA adduct protons are provided in Table S5 of the Supporting Information. The ABA H4 proton displayed multiple NOEs with the deoxyribose protons of nucleotide X5, indicating that it was closer in space to the deoxyribose as compared to the ABA H6 proton, which displayed only a single NOE to the complementary strand. A total of 25 NOEs between adduct protons and deoxyribose and base protons for both the modified and complementary strands were identified (Figure 4). Of these, ABA protons H2, H4, and H5 showed nine interactions with the modified strand and ABA protons H6, H8, H9, and H10 showed sixteen interactions with the complementary strand. No NOEs to either the modified or complementary strand of the duplex were observed for either ABA protons H1 or H11. A resonance was observed at 9.24 ppm in the H2O spectrum of the modified duplex. This may represent the ABA 3-NH proton present at the point of attachment between the adduct and the C8 of the modified base. However, the assignment remained equivocal because no NOEs were observed for this proton. This was attributed to the rapid exchange of the ABA 3-NH proton with solvent.

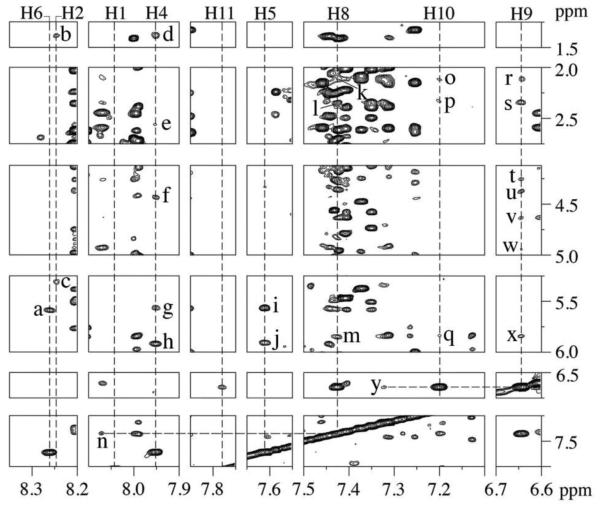

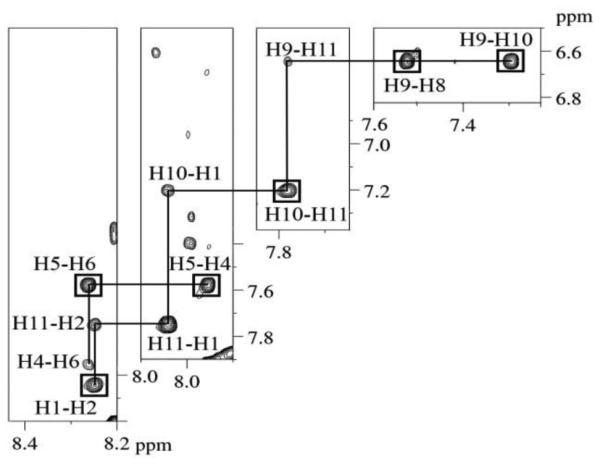

Figure 3.

Expanded plots of regions of the NOESY spectrum of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex, showing NOEs associated with the ABA cross-peaks (Chart 1). The boxed cross-peaks represent cross-peaks that are simultaneously observed in COSY spectra. In all cases, the cross-peaks are labeled to indicate proton resonances associated with the vertical (t1) axis first and proton resonances associated with the horizontal (t2) axis second. The 900 MHz spectrum was acquired at 15 º C using a 250 ms mixing time.

Figure 4.

Expanded plots of a NOESY spectrum of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex showing NOEs between adduct protons (Chart 1) and base and deoxyribose protons. The ABA H2, H4, and H5 protons presented NOEs to protons of the modified stand of the duplex. The ABA H8, H9, and H10 protons presented NOEs to the complementary strand of the duplex. The ABA H1 and H11 protons displayed no NOEs with either strand of the duplex. The cross-peaks are assigned as follows: a, ABA H6 → G21 H1´; b, ABA H2 → T6 CH3; c, ABA H2 → C4 H5; d, ABA H4 → T6 CH3, e, ABA H4 → X5 H2´´; f, ABA H4 → X5 H4´; g, ABA H4 → T6 H1´; h, ABA H4 → X5 H1´; i, ABA H5 → T6 H1´; j, ABA H5 → X5 H1´; k, ABA H8 → A19 H2´´; l, ABA H8 → A19 H2´; m, ABA H8 → A19 H1´; n, ABA H8 → C20 H6; o, ABA H10 → A19 H2´´; p, ABA H10 → A19 H2´; q, ABA H10 → A19 H1´; r, ABA H9 → A19 H2´´; s, ABA H9 → A19 H2´; t, ABA H9 → C20 H5´; u, ABA H9 → C20 H5´´; v, ABA H9 → C20 H4´; w, ABA H9 → A19 H3´; x, ABA H9 → A19 H1´; y, ABA H9 → A19 H8. The 900 MHz spectrum was acquired at 15 º C using a 250 ms mixing time.

Unmodified Duplex

The NMR data from the unmodified duplex was unremarkable, and the spectra of the unmodified duplex were fully assignable. The NOESY spectrum displayed two separate sets of continuous connectivity in the H6/H8 to H1' section of the spectrum which could be assigned to the primary and complementary strands of the DNA duplex (Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). The complete assignment of the spectrum did not reveal significant chemical shift perturbations, indicating a duplex conformation in the B-DNA67 family.

Chemical Shift Perturbations

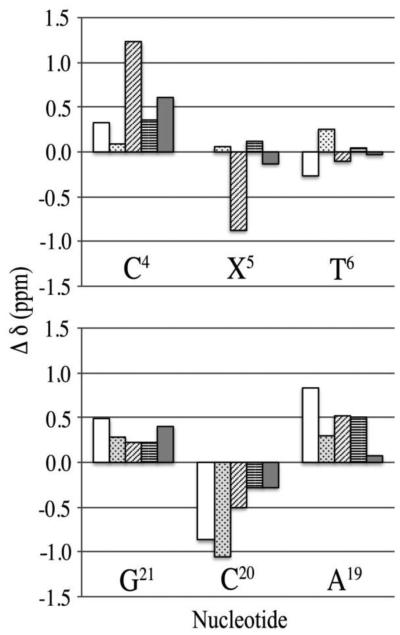

Chemical shift perturbations observed in the NMR spectra for the adducted nucleotide and surrounding nucleotides of the modified duplex as compared to the unmodified spectra are shown in Figure 5. Significant chemical shift perturbations were observed in the region of the adducted nucleotide, particularly for nucleotides C4, X5, and T6 and A19 and C20. The C4 nucleotide exhibited upfield changes in chemical shifts for the H6, H1´, H2´, H2´´, and H3´ protons of 0.33, 0.09, 1.23, 0.36, and 0.60 ppm, respectively. The X5 H8 proton is replaced by the adduct but the H1´, H2´, H2´´, and H3´ deoxyribose protons exhibited changes in shifts of 0.06 ppm upfield, 0.87 ppm downfield, 0.12 ppm upfield, and 0.13 ppm downfield, respectively. The T6 protons displayed downfield changes in chemical shifts of 0.27, 0.10, and 0.03 ppm for the H6, H2´, and H3´ protons and upfield shift changes of 0.26 and 0.05 ppm for the H1´, and H2´´ protons, respectively. For bases in the complementary strand, the A19 nucleotide protons displayed upfield changes in chemical shift of 0.84 ppm for H8, 0.30 ppm for H1´, 0.52 ppm for H2´, 0.50 ppm for H2´´, and 0.08 ppm for H3´. The C20 nucleotide protons exhibited downfield changes in chemical shift of 0.89, 1.05, 0.50, 0.28, and 0.28 ppm, for protons H6, H1´, H2´, H2´´, and H3´, respectively. The G21 nucleotide protons displayed upfield changes in chemical shift for the H8, H1´, H2´, H2´´, and H3´ protons of 0.49, 0.28, 0.23, 0.22, and 0.40 ppm respectively. Nucleotides distal to the adducted nucleotide displayed minimal chemical shift perturbations, predominantly less than 0.1 ppm, suggesting that these regions maintained a conformation similar to the unmodified duplex. Exceptions to this were the C18 H6, H1´, H2´, and H2´´ protons, which exhibited upfield changes in shifts of 0.19, 0.16, 0.31, and 0.30 ppm, respectively, and A17 H2´´, which exhibited an upfield change in chemical shift of 0.12 ppm.

Figure 5.

Changes in chemical shifts for the protons of the ABA modified and surrounding nucleotides of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex as compared to the unmodified duplex. Top Panel: Nucleotides of the modified strand, showing nucleotides C4 through T6. Bottom Panel: Nucleuotides of the complementary strand showing nucleotides A19 through G21. The base aromatic H6 or H8 protons are shown in white. The deoxyribose H1´ protons are shown in dots, the H2´ protons are shown in diagonal lines, the H2´´ protons are shown in horizontal lines, and the H3´ protons are shown in gray. The ?δ (ppm) values are calculated as δunmodified duplex- δmodified duplex. Positive values of Δδ represent upfield shifts and negative values of Δδ represent downfield shifts, with respect to the unmodified duplex.

Structural Refinement

A total of 320 NOE derived distance restraints were obtained from analyses of NOESY spectra for non-exchangeable protons collected at 15 ºC or 25 ºC (Table S6 in the Supporting Information). These included 125 internucleotide restraints, 171 intranucleotide restraints, and 24 adduct restraints. Additionally, proximal to the lesion site, 10 anti-distance restraints (Table S7 in the Supporting Information), placing a lower bound of 5 Å and an upper bound of 10 Å upon interproton distances, were employed. These were utilized in instances in which specific NOEs were not observed in the spectra. In such instances it was concluded that the failure to observe an NOE indicated that the protons in question were a minimum of 5 Å apart. Additional restraints included 90 backbone torsion angles, 42 hydrogen bond restraints, and 75 deoxyribose pseudorotation restraints, for a total of 537 restraints (Table 1). The latter were included as empirical restraints based on canonical B-DNA,57 which was consistent with NMR data.

Table 1.

NMR restraints used for the C8-dG-ABA structure calculations and refinement statistics.

| NOE restraints | |

| Internucleotide | 125 |

| Intranucleotide | 171 |

| C8-dG-ABA Adduct | 24 |

| Anti-distance restraintsa | 10 |

| Total | 330 |

| Backbone torsion angle restraints | 90 |

| Hydrogen bonding restraints | 42 |

| Deoxyribose pseudorotaton restraints | 75 |

| Total number of restraints | 537 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Number of distance restraint violations | 64 |

| Number of torsion restraint violations | 10 |

| Total distance penalty/maximum penalty (kcal/mol) | 5.0/0.296 |

| Total torsion penalty/maximum penalty (kcal/mol) | 0.39/0.118 |

| r.m.s. distances (Å) | 0.013 |

| r.m.s. angles (°) | 2.3 |

| Distance restraint force field (kcal/mol/Å2) | 32 |

| Torsion restraint force field (kcal/mol/deg2) | 32 |

These represent restraints fixing distances of greater than 5 Å in instances in which no NOE was observed between two protons of interest, suggesting that they must be greater than 5 Å apart.

A series of restrained molecular dynamics (rMD) calculations employing a simulated annealing protocol yielded ten emergent structures, from which an average structure was calculated. An overlay of the ten emergent structures and the final average and minimized structure indicated excellent convergence, and is shown in Figure 6. The ten emergent structures had a maximum rms pairwise difference of 0.59 Å and the average structure had a maximum rms pairwise difference of 0.40 Å, as compared to the ten individual structures. This indicated that there were sufficient experimental restraints to allow the rMD calculations to define a well-converged structure. The refinement statistics are shown in Table 1.

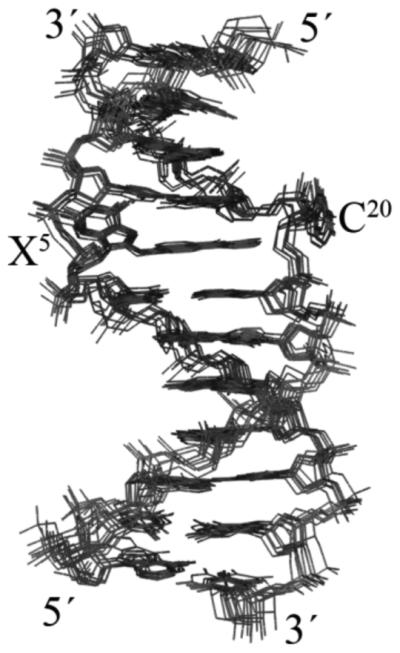

Figure 6.

Overlay of ten lowest energy violation structures resulting from rMD calculations of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex carried out using a simulated annealing protocol and using NOE generated distance restraints. The view is looking into the major groove.

The average structure emergent from the rMD calculations was evaluated as to its accuracy by complete relaxation matrix analysis carried out using the program CORMA52 (Figure 7 & Table 2). Most individual internucleotide and intranucleotide sixth root residual RX1 values were less than 0.1, with the overall internucleotide and intranucleotide sixth root residual RX1 values being 8.2 × 10−2 and 9.7 × 10−2 respectively. The overall sixth root residual for the modified duplex RX1 value was 0.088. This indicated that the average refined structure was in agreement with NOE data.

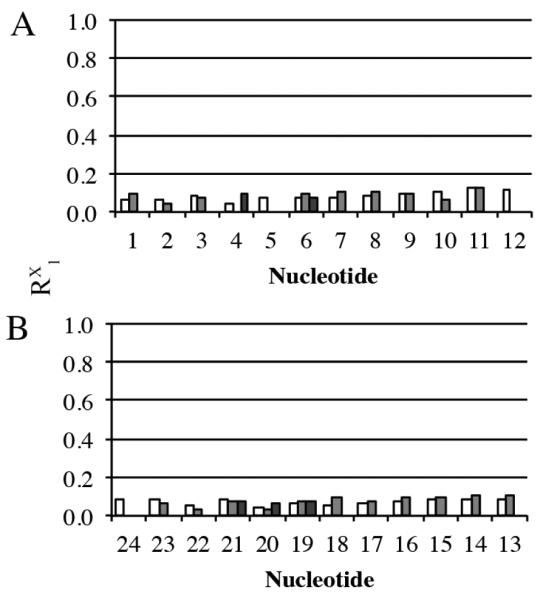

Figure 7.

Calculation of sixth root residual values (R1x) between theoretical NOEs predicted by complete relaxation matrix calculations and experimental NOEs for the averaged refined structure of the C8-dG-ABA duplex emergent from the rMD calculations, using the program CORMA. A. The intranucleotide, internucleotide and nucleotide to lesion RX1 values for individual nucleotides in the modified strand. B. The intranucleotide, internucleotide and nucleotide to lesion RX1 values for individual nucleotides in the complementary strand. The intranucleotide residuals are shaded in white. At the modified nucleotide X5, the intranucleotide residuals calculated for the C8-dG-ABA adduct are included with those of the X5 nucleotide. The DNA internucleotide residuals are shaded in gray. With the exception of the modified nucleotide X5, they indicate NOEs to the respective 3´-neighbor nucleotides. The internucleotide residuals between the C8-dG-ABA adduct and other nucleotides are shaded in dark gray. These involve nucleotides C4, T6, A19, C20, and G21. In all cases, the sixth root residual factor was calculated as R1x = ∑[((Io)i1/6)-((Ic)i1/6)/∑((Io)i1/6)], in which Ic are NOE intensities calculated by complete relaxation matrix analysis of the refined structure and Io are experimental NOE intensities.

Table 2.

RMS differences and sixth root residual RX1 values calculated for the average structure.

| Average structure (calculated from ten structures emergent from the simulated annealing rMD calculations) |

|||

|

| |||

| rms pairwise difference between structures | 0.592 | ||

| rms difference from average structure | 0.397 | ||

|

| |||

| Complete Relaxation Matrix Analysis for the Calculated Average Structure, Using the Program CORMAa |

|||

|

|

|||

| Intranucleotide | Internucleotide | Total | |

|

| |||

| Rx1b | 0.081 | 0.092 | 0.085 |

| Average errorc | 0.019 | ||

Mixing time was 250 ms

RX1 is the sixth root R factor: Σ[(( Io)i1/6)-((Ic)i1/6)/Σ((Io)i1/6)]

Average error: Σ(Ic-Io)/n where Ic are NOE intensities calculated from the refined structure and Io are experimental NOE intensities

A parallel set of rMD calculations using a simulated annealing protocol was performed, in which the 10 anti-distance restraints proximate to the lesion site were not employed. The refined structures emergent from this set of calculations were similar to those emergent from the calculations that employed the anti-distance restraints, indicating that the utilization of anti-distance restraints was not significantly biasing the rMD calculations. The set of ten structures emergent from the rMD calculations performed without the anti-distance restraints had a maximum rms pairwise difference of 0.58 Å (Table S8 in the Supporting Information). The structural features did not differ significantly from those of the structure determined using the anti-distance restraints, as shown in Figure S4 in the Supporting Information. The RMS pairwise difference between the structures obtained with and without the use of anti-distance restraints was 0.48 Å. One notable difference was a reduced degree of displacement for the C20 base. The C2 and N3 edge of C20 was oriented 1.8 Å closer to the ABA adduct while the C5 and C6 edge of C20 was oriented in a similar position compared to the structure determined with the use of anti-distance restraints. In the absence of the anti-distance restraints, the C20 deoxyribose was also shifted 0.6 Å closer to the ABA adduct.

Another parallel set of rMD calculations was carried out at constant temperature, in which the X5 base was initially placed into the anti conformation about the glycosidic bond. The structures that emerged from these calculations displayed greater disagreement with the NOE data, as determined by complete relaxation matrix analysis.52 The average intranucleotide and internucleotide RX1 values for the C4, X5, T6, A19, C20, and G21 nucleotides were calculated for both the structure with the adducted guanine in the syn conformation and the structure with the adducted guanine in the anti conformation. The structure with the adducted guanine in the syn conformation about the glycosidic bond displayed an average RX1 value of 6.8 × 10−2 for these nucleotides. The structure with the adducted guanine in the anti conformation about the glycosidic bond displayed an average RX1 value of 9.0 × 10−2 for these nucleotides. Most distances between protons at the lesion site were within the range of the NOE derived restraint windows. Of the 41 restraints used, nine were outside the window with the largest violation being 0.07 Å. These values are shown in Table S9 in the Supporting Information. The violations were determined to be acceptable as each of the nine values falling outside of the window possessed deviations that were small and were associated with restraints possessing higher error margins. These restraints were connected to NOEs that were weak, broadened, overlapped, or a combination of these factors.

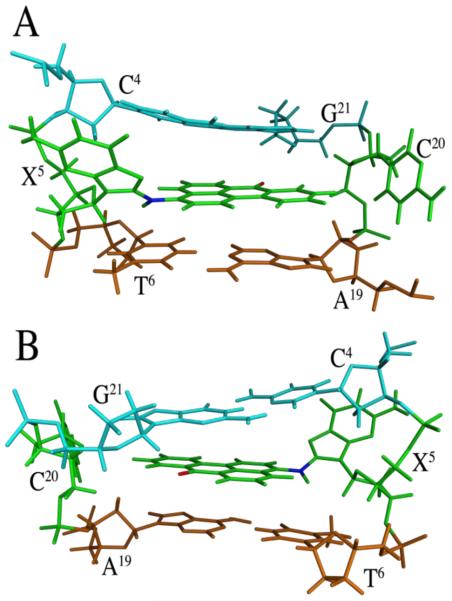

Conformation of the C8-dG-ABA Adduct

Figures 8 and 9 show views of the C8-dG-ABA adduct, based upon the lowest energy violation structure that emerged from the rMD calculations. This structure is in good agreement with the average structure. The modified guanine was shifted into the syn conformation about the glycosidic bond. This placed the base in proximity to the C4 deoxyribose protons and altered the deoxyribose pucker to the 3'-endo conformation for the X5 deoxyribose. The ABA moiety intercalated between the A19 and G21 bases of the complementary strand. It was oriented such that the bay region of the ABA moiety, including protons H1, H2, H10, and H11, faced toward the major groove of the DNA. The ABA H9 proton faced toward the phosphodiester backbone of the complementary strand, between bases A19 and G21. The ABA H4, H5, H6, and H8 protons faced toward the minor groove of the DNA, as did the keto oxygen of the ABA moiety. The intercalation of the ABA moiety between the A19 and G21 bases of the complementary strand forced the C20 base to be displaced into the major groove (Figure 8 A). The alignment of the planar ABA arylamine between the A19 and G21 bases allowed for possible π-stacking interactions (Figure 9). Bases G1 and T2 and their complement on the 5´-side and from G7 through T12 on the 3´-side and their complement retained a structure similar to canonical B-DNA.

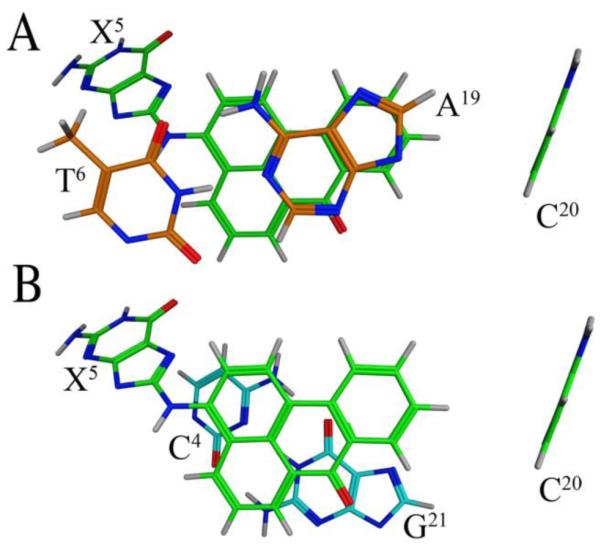

Figure 8.

Conformation of the C8-dG-ABA adduct as seen in the lowest violation structure emergent from rMD calculations. A. Base pairs C4:G21, X5:C20, and T6:A19 as seen from the major groove. B. Base pairs C4:G21, X5:C20, and T6:A19 as seen from the minor groove. The X5 base is rotated into the syn conformation at the glycosidic torsion angle; the C8-dG-ABA moiety is intercalated between base pairs C4:G21 and T6:A19; the complementary base C20 is displaced into the major groove. The C4 and G21 base carbon atoms are in cyan. The X5 and C20 base carbon atoms are in green. The T6 and A19 base carbon atoms are in orange. The adduct oxygen atom is shown in red and the nitrogen atom at the point of adduct attachment is shown in blue.

Figure 9.

Base stacking interactions of the C8-dG-ABA adduct as seen in the lowest violation structure emergent from rMD calculations. A. View looking through the duplex from the 3´-side of the ABA adduct showing carbon atoms of bases X5 and C20 in green and 3´-neighbor bases A19 and T6 in orange. B. View looking through the duplex from the 3´-side of the adducted nucleotide showing carbon atoms of bases of X5 and C20 in green and 5'-neighbor bases G21 and C4 in cyan. The oxygen atom of the adduct is shown in red and the nitrogen at the point of adduct attachment atoms is shown in blue.

Discussion

Of the three DNA adducts known to be formed following exposures to 3-NBA, the C8-dG-ABA adduct is believed to be the most significant contributor to mutagenic outcome.14 Thus, an understanding of the conformation of the C8-dG-ABA adduct in DNA is important, especially in light of human exposures to 3-NBA23 and its potential carcinogenicity in humans.24

Conformation of the C8-dG-ABA Adduct

The refined structure of the C8-dG-ABA adduct in this duplex reveals a base-displaced intercalated structure in which the modified base shifts into the syn conformation about the glycosidic bond. The usual method for evaluating the conformation of the glycosidic bond involves monitoring the intensity of the NOE between the guanine H8 proton and the guanine H1' proton; this NOE is strong when the purine base is in the syn conformation and weak when the base is in the anti conformation. However, this method is not applicable to C8-dG adducts, since these adducts do not possess a guanine H8 proton. A large body of work with bulky C8-adduct base-displaced intercalated structures in which the adducted base is shifted into the syn conformation39, 42, 43 has revealed that the chemical shifts of the deoxyribose H2' and H2" protons are also diagnostic markers of syn vs. anti conformation with respect to the glycosidic bond. In the present instance, the significant changes in chemical shifts of 1.23 ppm upfield and 0.87 ppm downfield for the C4 H2' and X5 H2' protons respectively, are consistent with the conclusion that the C8-dG-ABA adduct orients in the syn conformation about the glycosidic bond. This conclusion is also consistent with the predictions of complete relaxation matrix (CORMA) calculations52 performed upon structures emergent from the rMD calculations. These revealed that structures emergent from constant temperature rMD calculations, for which the X5 base was placed in the anti conformation about the glycosidic bond, displayed greater disagreement with the NOE data. In that instance, for nucleotides C4, X5, and T6 and A19, C20, and G21, the average sixth root residual RX1 with respect to the experimental NOE data obtained from the anti conformation is 9.0 while that obtained from the syn conformation is 6.8. The orientation of the intercalated arylamine ring of the ABA moiety is established by the sixteen NOEs between ABA H6, H8, H9, and H10 protons and those of the complementary strand, including protons of nucleotides A19, C20, and G21, indicating that this face of the adduct is positioned near the C20 deoxyribose and close to the area that would be occupied by the C20 base in a Watson-Crick base pair. This positioning of the aryl moiety allows for π stacking between the aryl ring and the A19 and G21 bases. Indeed, significant upfield changes in chemical shifts for the A19 H8 and G21 H8 proton resonances of 0.84, and 0.49 ppm, respectively, are consistent with such stacking interactions. A comparison of Figures 9A and 9B suggests a greater potential for stacking between the aryl ring with the A19 base. This may be reflected in the 0.35 ppm greater chemical shift perturbation of the A19 H8 proton resonance as compared to the G21 H8 proton resonance. The breaks in the sequential NOEs between base aromatic and deoxyribose H1' protons identified in the complementary strand and weak the NOEs between C20 H1' and C20 H6 and C20 H1' and G21 H8 support the conclusion that the C20 base is displaced from the duplex into the major groove. In addition, the large downfield chemical shifts observed for the C20 H8 and H1' proton resonances are also consistent with this conclusion. NOEs observed between the C20 H5 proton and the aromatic H9 and H10 protons of the adduct indicate the C20 base is displaced into the major groove and not the minor groove of the duplex.

Thermodynamic Effects of the C8-dG-ABA Adduct

In this sequence, the C8-dG-ABA adduct decreases the melting temperature (Tm) by 11 ºC. The decreased thermal stability of the duplex is reflected in the NMR spectra. For example, in Figure 2, broadening of the T6 N3H imino resonance and in the broadening of the NOE cross-peak between the T6 imino proton and A19 H2 proton may be attributed to an increased rate of exchange between the T6 N3H imino proton and water, likely the consequence of thermodynamic dynamic destabilization of the duplex. In this regard, the displacement of the C20 base into the major groove results in the loss of one base pair and the π-stacking interactions for this base. Furthermore, transition of the X5 base into the syn conformation about the glycosidic bond results in further loss of π-stacking interactions. Thus, despite the fact that the base-displaced intercalated conformation of the ABA moiety facilitates π-stacking between the intercalated aryl ring and neighboring bases, these new stacking interactions are evidently not sufficient to compensate for the loss in stability contributed by other sources. These may include loss of π-stacking interactions from the modified guanine base and its complementary cytosine base, as well as the loss of the hydrogen bonds contributed by this base pair. Additionally, some degree of helix unwinding may be present. As reported by Mu et al.68, unwinding of the helix leads to a decrease in stability and potential alterations in other π-stacking interactions of the duplex.

Comparisons to Other C8-dG Aryl Amine Adducts

Other bulky C8-dG aryl amine adducts have been examined as to conformation when placed between two pyrimidine bases in the 5'-d(CGC)-3':5'-d(GCG)-3' sequence. The C8-dG-IQ,41 8-[N-acetyl-aminofluorene]-2'-deoxyguanosine (AAF),40 C8-dG-AP,39 C8-dG-IQ,43 and C8-dG-PhIP42 adducts also exhibit base-displaced intercalated structures in this sequence. The base-displaced intercalated conformation of the C8-dG-ABA adduct in the 5'-d(CGC)-3':5'-d(GCG)-3' sequence exhibits similarities to these other C8-dG arylamine adducts. In general, these bulky C8-dG adducts are destabilizing when placed in this sequence, typically exhibiting decreases in Tm of between 10 ºC to 14 ºC.69, 70 However, the C8-dG-IQ adduct produced just a 4 ºC decrease in duplex Tm70 and the C8-dG-AP adduct also exhibited a decreased Tm of 5.9 ºC, though this was in the 5´-TXA-3´ sequence.71

It has been proposed that the propensity for C8-dG aryl amine lesions to assume base-displaced intercalated conformations is, in part, related to the steric potential of the hydrophobic aryl amine moieties to intercalate into the DNA duplex.41, 72, 73 Shapiro et al.73 recognized the potential role of hydrophobic surface area and suggested that C8-dG adducts having ring structures possessing greater surface area provide a greater hydrophobic area favoring base-displaced intercalation. The C8-dG-ABA adduct exhibits a surface area similar to the C8-dG AAF and C8-dG-PhIP adducts, calculated using the program Vega ZZ.74 In comparison, the C8-dG AP adduct has a somewhat smaller surface area of about 91% that of the larger adducts. The C8-dG-AF and C8-dG-IQ adducts possess the smallest surface area, about 84% that of the large adducts. In the 5'-d(CGC)-3':5'-d(GCG)-3' sequence the C8-dG-ABA adduct forms only the base-displaced intercalated structure as does the C8-dG-AAF40 adduct. However, the similar sized C8-dG-PhIP adduct exhibits a minor external conformation.42 The intermediate surface area C8-dG-AP adduct39 and the small surface area C8-dG-IQ adduct43 display only one conformation but the small surface area C8-dG aminofluorene (AF) lesion equilibrates between the base-displaced intercalated conformation characterized by the syn alignment and an external conformation characterized by the anti alignment of the glycosidic torsion angle.41, 72

Consequently, it is now recognized that factors in addition to hydrophobic effects related to surface area must contribute to the formation of base-displaced intercalated structures. DNA sequence is important. Wang et al.43, 75 examined the conformation of the C8-dG-IQ adduct placed at differing positions in the NarI restriction site sequence, a hotspot for frameshift mutations in bacteria. They documented the role of sequence in determining adduct conformation; the conformations of the adduct in the 5'-CXG-3' and 5'-GXC-3' sequences were similar and groove-bound,75 whereas in the 5'-CXC-3' sequence, the base-displaced intercalated conformation was favored.43 These sequence effects are consistent with the contributing role of electronic π-stacking interactions. The phenyl ring of the C8-dG-PhIP adduct favors an orientation out-of-plane with respect to the IP ring resulting in a greater unwinding for the duplex. This increases the distance between the PhIP moiety and the neighboring base pairs and reduces π-stacking efficiency of the PhIP ring.42 In the 5'-d(CGC)-3':5'-d(GCG)-3' sequence the C8-dG-IQ adduct43 stacks with both the 3´and 5´neighbors and the adducted guanine remains in a position that allows for additional stacking interactions. Favorable electronic dipole-dipole interactions between the heterocyclic IQ ring and neighboring DNA bases may enhance stacking.

Comparison to the N2-dG-ABA Adduct

The conformation of the C8-dG-ABA adduct in this sequence, 5'-d(CGT)-3':5'-d(ACG)-3', differs from the conformation of the N2-dG-ABA adduct, elucidated by Lukin et al.38 in the 5'-d(TGC)-3':5'-d(GCA)-3' sequence. The N2-dG-ABA adduct oriented in the minor groove pointing towards the 5' end of the duplex and the modified guanine remained in the anti configuration about the glycosidic bond, enabling the complementary cytosine to remain inserted into the duplex.38 Furthermore, in contrast to the present results indicating that the C8-dG-ABA adduct lowers the Tm of this duplex, the N2-dG-ABA adduct examined by Lukin et al.38 increased the Tm value. Thus, we conclude that regiochemistry, both with respect to resonance structures of the nitrenium ion, the proximate electrophile with regard to DNA alkylation (Chart 2),5, 21, 26-32 and with regard to different nucleophilic sites on the DNA bases14, 33-35 (Chart 3), plays significant roles in determining the conformational and thermodynamic effects induced by DNA adducts arising from human exposures to 3-NBA.

Structure-Activity Relationships

Although the C8-dG-ABA and N2-dG-ABA38 adducts have been examined in differing sequence contexts [5'-d(TGC)-3':5'-d(GCA)-3' vs. 5'-d(CGT)-3':5'-d(ACG)-3'], it seems likely that thermodynamic and conformational differences may modulate the repair efficiencies of C8-dG-ABA vs. N2-dG-ABA adducts. That the C8-dG-ABA adduct is a better substrate for NER, as compared to the N2-dG-ABA adduct,14 is consistent with the observation that while the C8-dG-ABA adduct lowers the Tm of this duplex, the N2-dG-ABA adduct examined by Lukin et al.38 increased the Tm value. The thermodynamic differences between the C8-dG-ABA and N2-dG-ABA adducts bear similarities with the corresponding adducts arising from the heterocyclic amine food mutagen 8-[(3-methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinolin-2-yl)amino]-2'-deoxyguanosine (IQ). In rat tissues the N2-dG-IQ adduct is more persistent than was the C8-dG-IQ adduct.76 As well, the relative thermal stability of the N2-dG-IQ adduct as compared to the corresponding unmodified duplex was also noted when this adduct favored base-displaced intercalated conformations in both the 5'-CXC-3' sequence,77 and the 5'-CXG-3' sequence,78 the C8-dG-IQ adduct reduced the thermal stability of the DNA.70, 79 The minimal effects of the N2-dG-IQ adducts upon the Tm values of the duplexes may explain the persistence of this adduct in rat tissues,76 consistent with the notion that the increased thermal stability as compared to the C8-dG-IQ adducts may correlate with decreased NER efficiency. Consequently, it was proposed that the C8-dG-IQ adduct contributes more towards the genotoxic properties of IQ.80 The role of DNA sequence in modulating the conformations and biological processing of bulky C8-dG adducts is established, with particular emphasis upon the NarI restriction sequence, a hotspot for frameshift mutagenesis in E. coli.81-86 In this regard, the contributions of the flanking base pairs are likely important; the modulation of both NER and polymerase bypass of C8-dG arylamine adducts as a function of 3'-flanking sequence, attributed to differential conformational effects, including the orientation of base stacking, has been noted by Jain et al.87-89 It will thus be of interest to examine sequence-specific conformational effects exhibited by the C8-dG-ABA and N2-dG-ABA adducts, and their possible relationships to both DNA repair and error-prone lesion bypass by Y-family polymerases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Markus Voehler for assistance with NMR. We thank Dr. Marion W. Calcutt for assistance with mass spectrometry. We thank Dr. Ewa Kowal and Dr. Kallie Stavros for helpful assistance and in training in NMR and other techniques.

Funding Sources

We acknowledge funding provided by NIH grants R01 CA-55678 (M.P.S.), R01 ES-009127 (A.B.), and R01 ES-021762 (A.B.). The Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center is funded by NIH grant P30 CA-068485. The Vanderbilt Center in Molecular Toxicology is funded by NIH grant P30 ES-000267. Funding for the NMR spectrometers was provided by in part by instrumentation grants S10 RR-05805, S10 RR-025677, and National Science Foundation Instrumentation Grant DBI 0922862, the latter funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-5). Vanderbilt University assisted with the purchase of NMR instrumentation. Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ABA

aminobenzanthrone

- AP

aminopyrene

- AF

aminofluorene

- B[a]P

benzo[a]pyrene

- C8-dG-ABA

N-(deoxyguanosin-8-yl)-3-aminobenzanthrone

- C8-dG-IQ

8-[(3-methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinolin-2-yl)amino]-2'-deoxyguanosine

- CORMA

complete relaxation matrix analysis

- COSY

correlation spectroscopy

- IARC

International Association for Research on Cancer

- IQ

8-[(3-methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinolin-2-yl)amino]-2'-deoxyguanosine

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization

- N2-dG-ABA

2-(deoxyguanosin-N2-yl)-3-aminobenzanthrone

- N6-dA-ABA

2-(deoxyadenosin-N6–yl)-3–aminobenzanthrone

- 3-NBA

3-nitrobenzanthrone

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance, 1-NP, 1-nitropyrene

- PhIP

2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine

- TLS

translesion synthesis

- TOCSY

total correlation spectroscopy

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information Available: The supporting information includes Tables S1, NMR resonance assignments and chemical shifts (ppm) for the non-exchangeable DNA protons of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex; S2, NMR resonance assignments and chemical shifts (ppm) for the exchangeable DNA protons of the unmodified duplex; S3, NMR resonance assignments and chemical shifts (ppm) for the exchangeable DNA protons of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex; S4, NMR resonance assignments and chemical shifts for the ABA protons of the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex; S5, NOE distance restraints used for rMD calculations for the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex; S6, anti-distance restraints used for rMD calculations for the C8-dG-ABA modified duplex; and Figures S1, partial charges and bond lengths for the C8-dG-ABA adduct, used in rMD calculations; S2, expanded plots of NOESY spectra at 15 ºC and 25 ºC comparing chemical shift overlaps for the ABA H8, T6 H6 and G21 H8 protons in the region of the spectrum showing NOEs between base aromatic and deoxyribose H1' cross-peaks; and S3, expanded plots from a NOESY spectrum of the 5'-d(GTGCGTGTTTGT)-3':5'-d(ACAAACACGCAC)-3' unmodified duplex showing the sequential NOE connectivity between aromatic H8/H6 protons and deoxyribose H1' protons. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Kielhorn J, Mangelsdorf I. Selected Nitro- and Nitro-oxy-polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Vol. 229. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. nited Nations Environment Programme, International Labour Organisation,World Health Organization, Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals, and International Program on Chemical Safety. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Murahashi T. Determination of mutagenic 3-nitrobenzanthrone in diesel exhaust particulate matter by three-dimensional high-performance liquid chromatography. Analyst. 2003;128:42–45. doi: 10.1039/b210174b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schuetzle D, Lee FSC, Prater TJ, Tejada SB. The identification of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) derivatives in mutagenic fractions of diesel particulate extracts. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1981;9:93–144. doi: 10.1080/03067318108071903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Paputapeck MC, Marano RS, Schuetzle D, Riley TL, Hampton CV, Prater TJ, Skewes LM, Jensen TE, Ruehle PH, Bosch LC, Duncan WP. Determination of nitrated polynuclear aromatic-hydrocarbons in particulate extracts by capillary column gas-chromatography with nitrogen selective detection. Anal. Chem. 1983;55:1946–1954. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Arlt VM, Stiborova M, Henderson CJ, Osborne MR, Bieler CA, Frei E, Martinek V, Sopko B, Wolf CR, Schmeiser HH, Phillips DH. Environmental pollutant and potent mutagen 3-nitrobenzanthrone forms DNA adducts after reduction by NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase and conjugation by acetyltransferases and sulfotransferases in human hepatic cytosols. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2644–2652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Murahashi T, Iwanaga E, Watanabe T, Hirayama T. Determination of the mutagen 3-nitrobenzanthrone in rainwater collected in Kyoto, Japan. J. Health Sci. 2003;49:386–390. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Enya T, Suzuki H, Watanabe T, Hirayama T, Hisamatsu Y. 3-nitrobenzanthrone, a powerful bacterial mutagen and suspected human carcinogen found in diesel exhaust and airborne particulates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997;31:2772–2776. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ames BN, McCann J, Yamasaki E. Methods for detecting carcinogens and mutagens with salmonella-mammalian-microsome mutagenicity test. Mutat. Res. 1975;31:347–363. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(75)90046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Maron DM, Ames BN. Revised methods for the Salmonella mutagenicity test. Mutat. Res. 1983;113:173–215. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(83)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fifer EK, Howard PC, Heflich RH, Beland FA. Synthesis and mutagenicity of 1-nitropyrene 4,5-oxide and 1-nitropyrene 9,10-oxide, microsomal metabolites of 1-nitropyrene. Mutagenesis. 1986;1:433–438. doi: 10.1093/mutage/1.6.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Arlt VM, Sorg BL, Osborne M, Hewer A, Seidel A, Schmeiser HH, Phillips DH. DNA adduct formation by the ubiquitous environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its metabolites in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2003;300:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Bieler CA, Cornelius MG, Stiborova M, Arlt VM, Wiessler M, Phillips DH, Schmeiser HH. Formation and persistence of DNA adducts formed by the carcinogenic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in target and non-target organs after intratracheal instillation in rats. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1117–1121. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Landvik NE, Arlt VM, Nagy E, Solhaug A, Tekpli X, Schmeiser HH, Refsnes M, Phillips DH, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Holme JA. 3-Nitrobenzanthrone and 3-aminobenzanthrone induce DNA damage and cell signalling Hepa1c1c7 cells. Mut. Res.-Fund. Mol. M. 2010;684:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kawanishi M, Fujikawa Y, Ishii H, Nishida H, Higashigaki Y, Kanno T, Matsuda T, Takamura-Enya T, Yagi T. Adduct formation and repair, and translesion DNA synthesis across the adducts in human cells exposed to 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Mut. Res.-Gen. Tox. En. 2013;753:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Purohit V, Basu AK. Mutagenicity of nitroaromatic compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:673–692. doi: 10.1021/tx000002x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Adachi S, Kawamura K, Takemoto K, Suzuki H, Hisamatsu Y. In: Relationships Between Acute and Chronic Effects of Air Pollution. Bates DV, editor. International Life Sciences Institute; 2000. p. 463. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Arlt VM, Gingerich J, Schmeiser HH, Phillips DH, Douglas GR, White PA. Genotoxicity of 3-nitrobenzanthrone and 3-aminobenzanthrone in Muta (TM) Mouse and lung epithelial cells derived from Muta (TM) Mouse. Mutagenesis. 2008;23:483–490. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gen037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Gadkari VV, Tokarsky EJ, Malik CK, Basu AK, Suo ZC. Mechanistic investigation of the bypass of a bulky aromatic DNA adduct catalyzed by a Y-family DNA polymerase. DNA Repair. 2014;21:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Phousongphouang PT, Grosovsky AJ, Eastmond DA, Covarrubias M, Arey J. The genotoxicity of 3-nitrobenzanthrone and the nitropyrene lactones in human lymphoblasts. Mut. Res.-Gen. Tox. En. 2000;472:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(00)00135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lamy E, Kassie F, Gminski R, Schmeiser HH, Mersch-Sundermann V. 3-nitrobenzanthrone (3-NBA) induced micronucleus formation and DNA damage in human hepatoma (HepG2) cells. Tox. Lett. 2004;146:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Arlt VM, Zhan L, Schmeiser HH, Honma M, Hayashi M, Phillips DH, Suzuki T. DNA adducts and mutagenic specificity of the ubiquitous environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in Muta Mouse. Env. Mol. Mutagen. 2004;43:186–195. doi: 10.1002/em.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hansen T, Seidel A, Borlak J. The environmental carcinogen 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its main metabolite 3-aminobenzanthrone enhance formation of reactive oxygen intermediates in human A549 lung epithelial cells. Tox. Appl. Pharm. 2007;221:222–234. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Seidel A, Dahmann D, Krekeler H, Jacob J. Biomonitoring of polycyclic aromatic compounds in the urine of mining workers occupationally exposed to diesel exhaust. Int. J. Hyg. Env. Health. 2002;204:333–338. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Baan RA, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Guha N, Loomis D, Straif K, International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group arcinogenicity of diesel-engine and gasoline-engine exhausts and some nitroarenes. Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:663–664. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Borlak J, Hansen T, Yuan ZX, Sikka HC, Kumar S, Schmidbauer S, Frank H, Jacob J, Seidel A. Metabolism and DNA-binding of 3-nitrobenzanthrone in primary rat alveolar type II cells, in human fetal bronchial, rat epithelial and mesenchymal cell lines. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds. 2000;21:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Gates KS, Nooner T, Dutta S. Biologically relevant chemical reactions of N7-alkylguanine residues in DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004;17:839–856. doi: 10.1021/tx049965c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Onozato M, Ohshima S. Analysis of mutagenicity of nitrobenzanthrones by molecular orbital calculations. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds. 2006;26:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Yang Z-Z, Qi S-F, Zhao D-X, Gong L-D. Insight into mechanism of formation of C8 adducts in carcinogenic reactions of arylnitrenium ions with purine nucleosides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:254–259. doi: 10.1021/jp804128s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Mizerovska J, Dracinska H, Arlt VM, Hudecek J, Hodek P, Schmeiser HH, Frei E, Stiborova M. Rat cytochromes P450 oxidize 3-aminobenzanthrone, a human metabolite of the carcinogenic environmental pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2008;1:150–154. doi: 10.2478/v10102-010-0031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Mizerovska J, Dracinska H, Frei E, Schmeiser HH, Arlt VM, Stiborova M. Induction of biotransformation enzymes by the carcinogenic air-pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in liver, kidney and lung, after intra-tracheal instillation in rats. Mut. Res.-Gen. Tox. En. 2011;720:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Stiborova M, Cechova T, Borek-Dohalska L, Moserova M, Frei E, Schmeiser HH, Paca J, Arlt VM. Activation and detoxification metabolism of urban air pollutants 2-nitrobenzanthrone and carcinogenic 3-nitrobenzanthrone by rat and mouse hepatic microsomes. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. 2012;33(Suppl 3):8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Xue JD, Du LL, Zhu RX, Huang JQ, Phillips DL. Direct time-resolved spectroscopic observation of arylnitrenium ion reactions with guanine-containing DNA oligomers. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:3610–3614. doi: 10.1021/jo500484s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kawanishi M, Enya T, Suzuki H, Takebe H, Matsui S, Yagi T. Postlabeling analysis of DNA adducts formed in human hepatoma cells treated with 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Mutat. Res. 2000;470:133–139. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Arlt VM, Schmeiser HH, Osborne MR, Kawanishi M, Kanno T, Yagi T, Phillips DH, Takamura-Enya T. Identification of three major DNA adducts formed by the carcinogenic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone in rat lung at the C8 and N2 position of guanine and at the N6 position of adenine. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;118:2139–2146. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kanno T, Kawanishi M, Takamura-Enya T, Arlt VM, Phillips DH, Yagi T. DNA adduct formation in human hepatoma cells treated with 3-nitrobenzanthrone: analysis by the 32P-postlabeling method. Mutat. Res. 2007;634:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pande P, Malik CK, Bose A, Jasti VP, Basu AK. Mutational analysis of the C8-guanine adduct of the environmental carcinogen 3-nitrobenzanthrone in human cells: Critical roles of DNA polymerases eta and kappa and Rev1 in error-prone translesion synthesis. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5323–5331. doi: 10.1021/bi5007805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Nishida H, Kawanishi M, Takamura-Enya T, Yagi T. Mutagenic specificity of N-acetoxy-3-aminobenzanthrone, a major metabolically activated form of 3-nitrobenzanthrone, in shuttle vector plasmids propagated in human cells. Mutat. Res. 2008;654:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lukin M, Zaliznyak T, Johnson F, de Los Santos CR. Incorporation of 3-aminobenzanthrone into 2'-deoxyoligonucleotides and its impact on duplex stability. J. Nucleic Acids. 20112011:521035. doi: 10.4061/2011/521035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Mao B, Vyas RR, Hingerty BE, Broyde S, Basu AK, Patel DJ. Solution conformation of the N-(deoxyguanosin-8-yl)-1-aminopyrene ([AP]dG) adduct opposite dC in a DNA duplex. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12659–12670. doi: 10.1021/bi961078o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).O'Handley SF, Sanford DG, Xu R, Lester CC, Hingerty BE, Broyde S, Krugh TR. Structural characterization of an N-acetyl-2-aminofluorene (AAF) modified DNA oligomer by NMR, energy minimization, and molecular dynamics. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2481–2497. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Mao B, Hingerty BE, Broyde S, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the aminofluorene [AF]-intercalated conformer of the syn-[AF]-C8-dG adduct opposite dC in a DNA duplex. Biochemistry. 1998;37:81–94. doi: 10.1021/bi972257o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Brown K, Hingerty BE, Guenther EA, Krishnan VV, Broyde S, Turteltaub KW, Cosman M. Solution structure of the 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine C8-deoxyguanosine adduct in duplex DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8507–8512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151251898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wang F, Demuro NE, Elmquist CE, Stover JS, Rizzo CJ, Stone MP. Base-displaced intercalated structure of the food mutagen 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline in the recognition sequence of the NarI restriction enzyme, a hotspot for -2 bp deletions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10085–10095. doi: 10.1021/ja062004v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).vom Brocke J, Krais A, Whibley C, Hollstein MC, Schmeiser HH. The carcinogenic air pollutant 3-nitrobenzanthrone induces GC to TA transversion mutations in human p53 sequences. Mutagenesis. 2009;24:17–23. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gen049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Cavaluzzi MJ, Borer PN. Revised UV extinction coefficients for nucleoside-5'-monophosphates and unpaired DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Bernardi G. Chromatography of nucleic acids on hydroxyapatite. I. Chromatography of native DNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1969;174:423–434. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(69)90273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Piotto M, Saudek V, Sklenar V. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. J. Biomol. NMR. 1992;6:661–665. doi: 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Goddard TD, Kneller DG. University of California, San Francisco. San Francisco, CA: 2006. SPARKY v. 3.113. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Jeener J, Meier BH, Bachmann P, Ernst RR. Investigation of exchange processes by 2-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 1979;71:4546–4553. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Wagner R, Berger S. Gradient-selected NOESY - A fourfold reduction of the measurement time for the NOESY experiment. J. Magn. Res. A. 1996;123:119–121. doi: 10.1006/jmra.1996.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Keepers JW, James TL. A theoretical study of distance determination from NMR. Tsourceo-dimensional nuclear Overhauser effect spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 1984;57:404–426. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Borgias BA, James TL. Two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser effect: Complete relaxation matrix analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1989;176:169–183. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)76011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).James TL. Relaxation matrix analysis of two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser effect spectra. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1991;1:1042–1053. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Borgias BA, James TL. MARDIGRAS--a procedure for matrix analysis of relaxation for discerning geometry of an aqueous structure. J. Magn. Reson. 1990;87:475–487. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Bruschweiler R, Blackledge M, Ernst RR. Multi-conformational peptide dynamics derived from NMR data: A new search algorithm and its application to antamanide. J. Biomol. NMR. 1991;1:3–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01874565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Ippel JH, Lanzotti V, Galeone A, Mayol L, van den Boogaart JE, Pikkemaat JA, Altona C. Conformation of the circular dumbbell d<pCGC-TT-GCG-TT>: Structure determination and molecular dynamics. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:403–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00197639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Arnott S, Hukins DWL. Optimised parameters for A-DNA and B-DNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1972;47:1504–1509. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(72)90243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adarno C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. GAUSSIAN09. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) Chemical Computing Group Inc. H3A. 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite #910; Montreal, QC, Canada: 2015. p. 2R7. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Schafmeister CEA, Ross WS, Romanovski V. University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA: 1995. XLEAP. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Case DA, Cheatham TE, 3rd, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Jr., Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. The AMBER biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Wang JM, Cieplak P, Kollman PA. How well does a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) model perform in calculating conformational energies of organic and biological molecules? J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Bashford D, Case DA. Generalized Born models of macromolecular solvation effects. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2000;51:129–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Thomas PD, Basus VJ, James TL. Protein solution structure determination using distances from two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser effect experiments: Effect of approximations on the accuracy of derived structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:1237–1241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]