Abstract

The modulation of chromatin status at specific genomic loci controls lymphoid differentiation. Here, we investigated the role played in this process by KAP1, the universal cofactor of KRAB-containing zinc finger proteins (KRAB-ZFP), a tetrapod-restricted family of transcriptional repressors. T lymphoid KAP1 knockout mice displayed expansions of specific T cell populations, with impaired responses to stimulation and deregulation of genes involved in cell survival, cytoskeletal rearrangement, and immune signalling. Furthermore, chromatin studies demonstrate that KAP1 directly regulates the expression of a number of these genes, among which Foxo1 seemed of particular interest. Likely at least partly responsible for these effects, a small number of KRAB/ZFPs are selectively expressed in T cells. These results reveal the as-of-yet unsuspected importance of the KRAB/KAP1 epigenetic regulation system for T cell differentiation and function.

Introduction

Heritable histone and DNA modifications at specific genomic loci, often collectively termed epigenetic modifications, play fundamental roles in the development of higher organisms, as highlighted by human developmental diseases due to mutations in components of the epigenetic machinery [1–3]. Epigenetics also conditions the homeostasis of adult tissues by regulating cell fate, and it has been proposed to be key to the differentiation and plasticity of the immune system [4]. In particular, T lymphoid specification seems to be tightly regulated by chromatin remodeling [5–7].

The T cell lineage arises from early thymic progenitors (ETP), which are bone marrow-derived uncommitted cells possibly still also endowed with potential for myeloid and/or B lymphoid differentiation [8]. Loss of multipotency occurs during the early stages of double negative (CD4-CD8-; DN) thymocyte differentiation and requires Notch1 signaling [9]. In late DN stages the crucial event for differentiation is the rearrangement of the T cell receptor β chain. Indeed, signaling through properly assembled pre-TCR (composed by TCRβ chain, CD3 and pre-Tα chain) is needed for further differentiation in double positive (CD4+CD8+; DP) thymocytes [10]. At this stage both CD4 and CD8 co-receptors are expressed and cells initiate TCR α chain rearrangement. DP thymocytes undergo positive and negative selections, that is, respectively, blockade of programmed cell death and elimination of auto-reactive clones. Both types of selection rely on TCR interaction with self peptide-MHC expressed on thymic epithelial cells [11]. Kinetic and threshold of TCR signaling seem to be also decisive for the differentiation of mature single positive (SP) CD4 or CD8 thymocytes, which is eventually driven by differential expression of the ThPok and Runx3 transcription factors, respectively [12–13]. After single positive specification, cells traffic through and egress from the thymus to migrate to secondary lymphoid organs. A main actor in this process is the transcription factors Klf2, which promotes expression of surface molecules involved in trafficking such as the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) [14]. All the aforementioned differentiation steps are driven by the integration of external stimuli with specific gene expression patterns. Thus, tight regulation of molecules tuning the sensitivity of the TCR and the correct expression of membrane receptors is fundamental, as shown by T developmental abnormalities in mice depleted of the Linker of Activation of T cells (LAT), the chemokine receptor CCR7 and the semaphorin receptor PlexinD1 [15–17]. On the other hand, to determine accessibility of lineage-specific target gene loci and restrict alternative gene expression pathways, chromatin must undergo modifications. This has been well demonstrated by the progressive chromatin compaction that takes place during thymocyte maturation, and the role of the zinc finger MAZR in regulating local chromatin status at the Cd8 and ThPok loci [6, 18]. Once in the periphery, naïve CD4+ and CD8+ cells are able to respond to antigens displayed by antigen-presenting cells, undergoing activation events that lead to clonal expansion and differentiation into effector cells, a process also influenced by epigenetic mechanisms [19].

Krüppel-Associated box Protein 1 (KAP1), also known as TRIM28 or TIF1β, is a ubiquitously expressed protein belonging to the TRIpartite Motif-containing (TRIM) family. KAP1 acts as scaffold protein that is tethered to genomic loci by the DNA-binding KRuppel-Associated Box Zinc Finger Proteins (KRAB-ZFP) and recruits chromatin modifiers such as SETDB1 histone methyltransferase, the CHD3/Mi2 component of the NuRD complex and Heterochromatin Protein 1 (HP1). These effectors induce the formation of heterochromatin initially by tri-methylation of histone 3 on lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and histone deacetylation [20–21] [22–23]. KRAB-ZFPs constitute a vast family of tetrapod-restricted transcription repressors, which underwent expansion by gene duplication during evolution [24–25]. They are characterized by tandem repeats of C2H2 zinc fingers at the C-terminus, which bind specific DNA target sequences, and one or two KRAB domains at the N-terminus, which recruits KAP1 [26–28]. Although the biochemical mechanism of action of the KRAB-ZFP/KAP1 system has been well established, at least in vitro, its in vivo functions remain ill defined. The constitutive knockout of KAP1 has been found to be lethal at day E5.5 in the mouse, correlating with a defect in gastrulation. KAP1 has also been demonstrated to partake in DNA damage response, control of behavioral stress and silencing of retroelements [29–33]. Moreover, specific KRAB-ZFPs have been implicated in imprinting, tumorigenesis and neuroprotection [34–36].

In the present work, we investigated the role of the KRAB/KAP1 system in T cell development and function. By conditionally knocking out KAP1 at the late DN T cell stage, we found that KAP1 modulates T cells differentiation and activation. Moreover, a combination of microarray gene expression and ChIP-seq analyses revealed that genes involved in survival, such as Bcl2, Bcl2l13, Fbxo31 and Glipr1, in migration and cytoskeleton rearrangement, such as G-coupled receptors and Capzb, and in activation and differentiation of T cells, such as Tgfbr2, Traf1, Il18r1 and Myd88 were dysregulated in KAP1-deleted thymocytes, reflecting for some direct control by KAP1. Interestingly, a major regulator of thymocyte transcriptional network, such as Foxo1, was also dysregulated upon KAP1 removal and subjected to its control. The identification of a small number of T cell-restricted KRAB-ZFPs further points to likely important mediators of these events.

Altogether, our findings provide important new information about the in vivo physiological function of KRAB/KAP1 and uncover a previously unknown role for this system in T cell development and homeostasis.

Results

Expansion of T cell compartment in KAP1 KO mice

In order to evaluate KRAB-ZFP/KAP1 role in T lymphocyte differentiation and function we generated a T-specific knockout mouse line, by crossing KAP1flox animals (Tif1βL3/L3; [29]) with heterozygous CD4-Cre mice. In this strain, the recombinase is expressed from a CD4 minigene that becomes active at the DN3 stage of thymocyte differentiation [37]. CD4-Cre/KAP1flox KO mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio and appeared normal and healthy.

As first, we evaluated the efficiency and specificity of KAP1 excision by PCR analysis of DNA extracted from DN, DP, SP CD4+ and CD8+ cells purified from the thymus of 8-12 weeks-old mice. Deletion was partial in DN cells and complete in DP, CD4+ and CD8+ cells, as expected. RT-PCR and Western blot analyses revealed that about 40% of KAP1 RNA and protein was left in thymus from KO animals, consistent with the mix of cells present in this organ. In contrast, KAP1 RNA was almost undetectable in mature CD4+ and CD8+ splenocytes of CD4-Cre/KAP1flox KO mice (Fig. 1A). KAP1 locus deletion was also specific for T lymphoid tissues (Fig. S1).

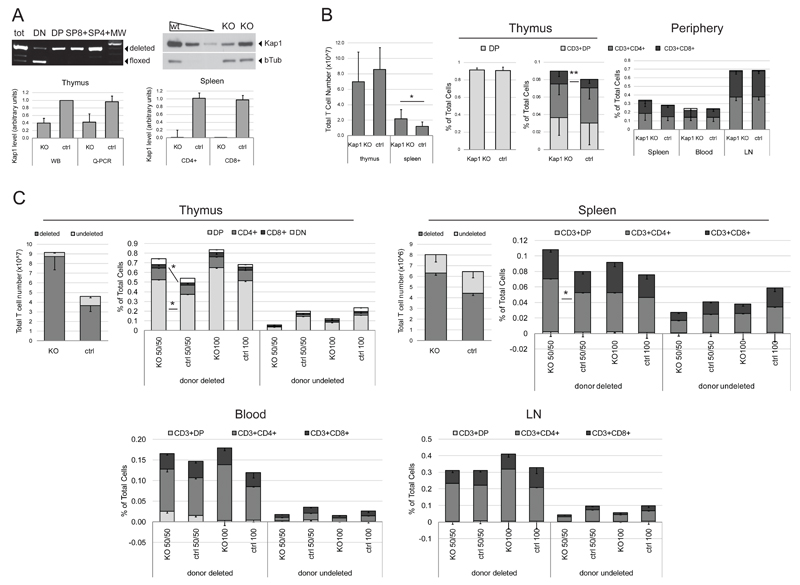

Figure 1. KAP1 knockout mice show altered T cell differentiation.

Thymus, spleen, blood and lymphnode (LN) harvest from 8-12 weeks old CD4-Cre/KAP1-flox (KAP1 KO) and littermate wt/KAP1-flox control mice (ctrl) were analyzed by PCR, Western Blot (WB) and Q-PCR (A) and flow cytometry (B). A) Upper left panel, thymocytes were sorted by flow cytometry on the basis of CD4 and CD8 expression and genomic DNA was analyzed by PCR. Amplified deleted and floxed locus bands are indicated. One representative experiment of two performed is shown. Upper right panel, T-enriched spleenocytes were analyzed by WB; anti-KAP1 and anti-βTubulin (βTub – loading control) antibodies were used. One representative experiment of two performed is shown. Lower panels, WB (n=4) and Q-PCR (n=7) quantification of KAP1 expression in thymocytes from KO and control mice (left). Q-PCR quantification of CD4+ and CD8+ sorted splenocytes (n≥4). Average + SD are shown. B) Left panel, total T cell number in the indicated populations is shown, *p= 0.0261 (n≥9). Middle panels, frequencies of the indicated population in total thymocytes, **p= 0.0017 (n≥19). Right panel, frequencies of the depicted populations in spleen (n≥19), blood (n≥8) and LN (n≥10) total cells. Average + or - SD are shown. C) CD45.1 chimeric mice obtained by transplant of 50% CD45.2+ CD4-Cre/YFP-flox/KAP1-flox + 50% CD45.1+ wild-type (KO 50/50; n=8), 50% CD45.2+ CD4-Cre/YFP-flox/KAP1-wt+ 50% CD45.1+ wild-type (ctrl 50/50; n=8), 100% CD45.2+ CD4-Cre/YFP-flox/KAP1-flox (KO 100; n=5) and 100% CD45.2+ CD4-Cre/YFP-flox/KAP1-wt (ctrl 100; n=4) lin- cells were sacrificed 6-10 weeks after injection and thymus (upper left), spleen (upper right), blood (lower left) and LN (lower right) cells were counted (only KO and ctrl 50/50 thymocytes and splenocytes are shown) and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD45.2+ YFP+ (donor deleted) and CD45.2+ YFP- (donor undeleted) subpopulations were analyzed as in B). Average - SEM are shown. Thymus DP *p=0.0207, CD8+ *p= 0.0104. Spleen CD4+ *p=0.0499. DP: double positive cells (CD4+CD8+), DN: double negative cells (CD4-CD8-). p values by Mann-Whitney test.

We then analyzed the phenotype of the KAP1 KO mice. We harvested primary and secondary T lymphoid organs from 8-12 week old CD4-Cre/KAP1flox and littermate control mice. Conventional histological studies revealed no significant differences between the two sets of animals (not illustrated). We thus assessed by flow cytometry the frequency of DN, DP, CD4+ and CD8+ cells in the thymus and in peripheral organs. We found a higher percentage of CD8+ thymocytes and a higher number of total T splenocytes in KAP1-deleted vs. control mice, suggesting some alteration in differentiation, migration and/or survival of T cells (Fig. 1B).

To explore this point further, we generated bone marrow chimeric mice by transplanting bone marrow-derived hematopoietic progenitor lineage negative (HPC lin-) KAP1-deleted and control cells expressing the CD45.2 antigen in competition with HPC lin- expressing the CD45.1 antigen. Also, we used mice generated from the breeding of our strain with the stopfloxYFP mouse strain as donors. This allowed for the monitoring of Cre activity, since the EYFP-coding sequence is preceded by a loxP-flanked stop sequence and expressed only upon excision of the stop sequence by the recombinase [38]. We could thus distinguish between deleted (YFP+) and undeleted (YFP-) cells in the donor-derived populations. After verifying that YFP-positivity strictly correlated with KAP1 excision (not illustrated), we generated 4 experimental groups: two groups received CD4-Cre/KAP1flox/stopfloxYFP CD45.2+ donor cells (KO) and two groups CD4-Cre/KAP1wt/stopfloxYFP CD45.2+ donor cells (ctrl), injected in competition with equal amounts of wild type CD45.1 cells (50/50) or alone (100). Flow cytometry analysis 6-10 weeks after transplantation revealed higher total numbers of donor-derived thymocytes in KO 50/50 group compared to ctrl 50/50 group (Fig. 1C). Accounting for this difference, there was expansion of DP and SP CD8+ cells in donor-derived YFP+ cells in mice engrafted with KAP1-deleted cells in competition with wild type cells (KO 50/50). The KAP1 deletion also affected the peripheral organs (blood, spleen and lymph nodes) of chimeric mice, with a general trend towards higher percentages and absolute numbers of T cells in donor-derived KAP1 KO cells when compared to donor-derived control cells, reaching statistical significance for CD4+ splenocytes (Fig.1C).

KAP1-deleted T cells are functionally impaired

Since chromatin modifications regulate TCR rearrangement [39], we asked if KAP1 removal affected this process. As KAP1 deletion was completed in our mice at the DP stage, when the TCRβ chain has already been rearranged, we compared by Q-PCR the frequency of the TCRα variable (TRAV) regions in KAP1-deleted and control DP, CD4+ and CD8+ thymocytes. The same level of TRAV polyclonality was recorded in KAP1-depleted and control thymocytes, indicating that the master regulator does not influence this late stage of TCR rearrangement (Fig. S2).

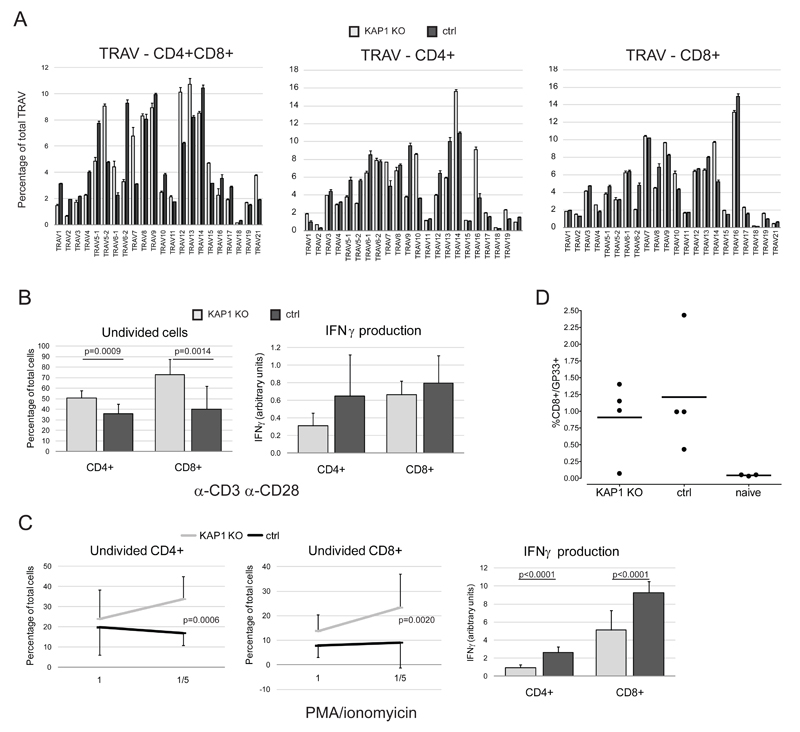

We then evaluated the ability of KAP1-deficient T cells to respond to activation in vitro. CD4+ and CD8+ splenocytes sorted from knockout and control mice were seeded on anti-CD3-coated dishes in the presence of anti-CD28 antibody and their proliferation and cytokine production profiles were evaluated 3 days later. When compared to control cells, both CD4+ and CD8+ KAP1-deleted cells exhibited lower levels of proliferation and interferon γ (IFNγ) production (Fig. 2A). In order to test if the defect was at the level of the TCR or of downstream signaling events, we next assessed the response of T cells to phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin, which activate PKC and calcium influx pathways, respectively, bypassing TCR stimulation. At high concentrations of PMA and ionomycin, KAP1-deleted and control CD4+ and CD8+ spleenocytes had the same rate of proliferation, while IFNγ production was severely impaired by KAP1 removal. At lower doses of PMA and ionomycin a defect in proliferation of deleted CD4+ and CD8+ cells was also evident (Fig. 2B). However, when we tested in vivo responses to viral immunization, we observed that knockout CD8+ cells were primed as efficiently as controls, as assessed by tetramer staining and flow cytometry analysis after injection of recombinant adenoviral vector expressing the LCMV glycoprotein GP33 (rAD/GP33) (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. KAP1-deleted T cells are partially impaired in function.

A) RNA extracted from CD4+CD8+ (left panel), CD4+ (middle panel) and CD8+ (right panel) thymocytes sorted from 8-12 weeks old CD4-Cre/KAP1-flox (KAP1 KO) and littermate wt/KAP1-flox control (ctrl) mice was retrotranscribed and analyzed by Q-PCR by using specific primers amplifying the variable regions of TCRα locus (TRAV). Frequency of each TRAV family is shown as average + SEM (n=3). B-C) CD4+ and CD8+ sorted spleenocytes were incubated in vitro in presence of α-CD3 (3μg/ml) and α-CD28 (1μg/ml) (B) or PMA and ionomycin (1=10ng/ml and 2ng/ml, 1/5= 2ng/ml and 0.4ng/ml, PMA and ionomycin, respectively) (C). Cells were analyzed 3-4 days later by CFSE staining and supernatant by ELISA assay specific for IFNγ. Average + or - SD are shown (n=4). IFNγ values are normalized to dividing cell percentages and assessed on highest concentration of stimulus for C. D) CD4-Cre/KAP1-flox (KAP1 KO) and littermate wt/KAP1-flox control (ctrl) were intra-muscle injected with adenoviral vector expressing LCMV glycoprotein (rAD/GP33). GP33 tetramer staining was performed 16 days later or 1 week after re-boosting. Percentages of GP33+ CD8+ cells are shown. Naïve= not immunized mice. One representative experiment out of two performed with similar results is shown.

These data indicate that in absence of KAP1 CD4+ and CD8+ cells are impaired, albeit not fully defective in responding to activation, suggesting a role for KAP1 downstream to TCR signaling, maybe at the level of threshold tuning.

Gene expression pattern in KAP1-deleted cells

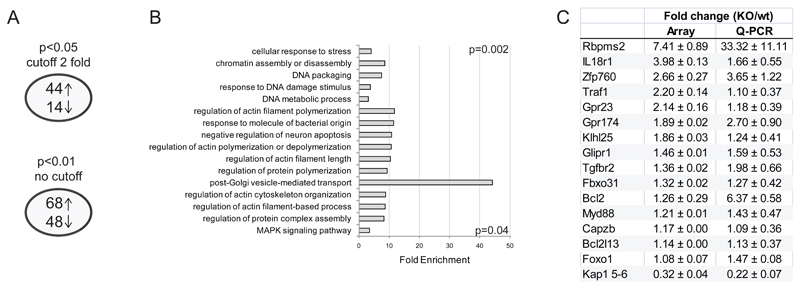

We then asked what changes were induced at the molecular level by KAP1 deletion. Since the major developmental abnormalities were observed in the thymus (see Fig.1), we analyzed gene expression in thymocytes harvested from 3 pairs of T lymphoid KAP1-deleted mice and littermate controls. After verifying that KAP1 depletion was greater than 70% in the KO samples (Fig. S2), we performed microarray analyses. We observed a mild change in the overall gene regulation when we applied a two-fold change cutoff, with 58 transcripts significantly altered in KO thymocytes (p<0.05), most of which were upregulated. This is consistent with the known role of KAP1 as gene silencer. As we cannot determine a priori the relevance of small changes in gene expression in this model, we also performed a no-cut-off analysis and found 116 significantly deregulated genes in KAP1-deleted thymocytes, 68 of which were upregulated and 48 downregulated (p<0.01; Fig. 3A; for a complete list of deregulated genes see Table S1). We next used the widest lists of dysregulated genes to interrogate the DAVID bioinformatic database [40–41]. Interestingly, we found chromatin and DNA packaging regulation among the most enriched gene ontology (GO) biological processes, together with cytoskeleton regulation pathways (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Gene Expression dysegulation in KAP1-deleted thymocytes.

A) Number of genes dysregulated in knockout thymocytes compared to controls, arrow up=number of upregulated genes, arrow down=number of deregulated genes. Upper and lower panels show numbers from two analyses performed with the depicted parameters. B) DAVID bioinformatic database analysis on the dysregulated genes (p<0.01, no cutoff). Gene ontology biological process classes of genes enriched in the dysregulated gene lists in KO thymocytes. Fold enrichment over background and highest and lowest p values are depicted. C) Fold change in expression levels of the indicated genes in knockout vs. wild type thymocytes as assessed in microarray and Q-PCR. Average ± SEM; n=3.

Some of the dysregulated genes appeared of interest in light of the phenotype observed in KAP1-deleted mice. In particular, the anti-apoptotic Bcl2l13, the regulator of cell cycle Fbxo31 and the apoptosis/survival regulator Glipr1 genes were found upregulated in KAP1-depleted thymocytes, supporting a role for KAP1 in the regulation of T cell homeostasis. We also found dysregulation of genes encoding for the F-acting capping protein Capzb and the G-coupled receptors Gpr23 and Gpr174, which might affect cytoskeleton rearrangement and thymocyte migration, in particular when considering the negative role of Gpr23 (also known as LPA4) in regulation of cell motility [42], reminiscent of the function of the S1P2 receptor, which is involved in the main pathway regulating thymocytes egress from thymus [43–44]. Finally, genes involved in survival, activation and differentiation of T cells, such as Tgfbr2, Traf1, Myd88 and Il18r1 were dysregulated upon KAP1 deletion. We confirmed by Q-PCR the dysregulation of these and of the genes encoding the BTB-kelch protein Klhl25, the RNA-binding protein Rbpms2 and the KRAB-ZFP760, which were found particularly upregulated in KAP1-deleted thymocytes. Because of their biological significance, we also evaluated by Q-PCR the expression pattern of two major regulators of T cell homeostasis, such as Bcl2 and Foxo1, which seemed to be dysregulated though not reaching significance in the microarray, and confirmed their dysregulation in KAP1-deleted thymocytes (Fig. 3c).

Overall, the observed transcriptional alterations strongly suggest that KAP1 regulates T cell survival/apoptosis, migration and signaling, and that disturbances in these pathways are the basis for the phenotype of KAP1 knockout mice.

KAP1 binding and chromatin modifications in T cells

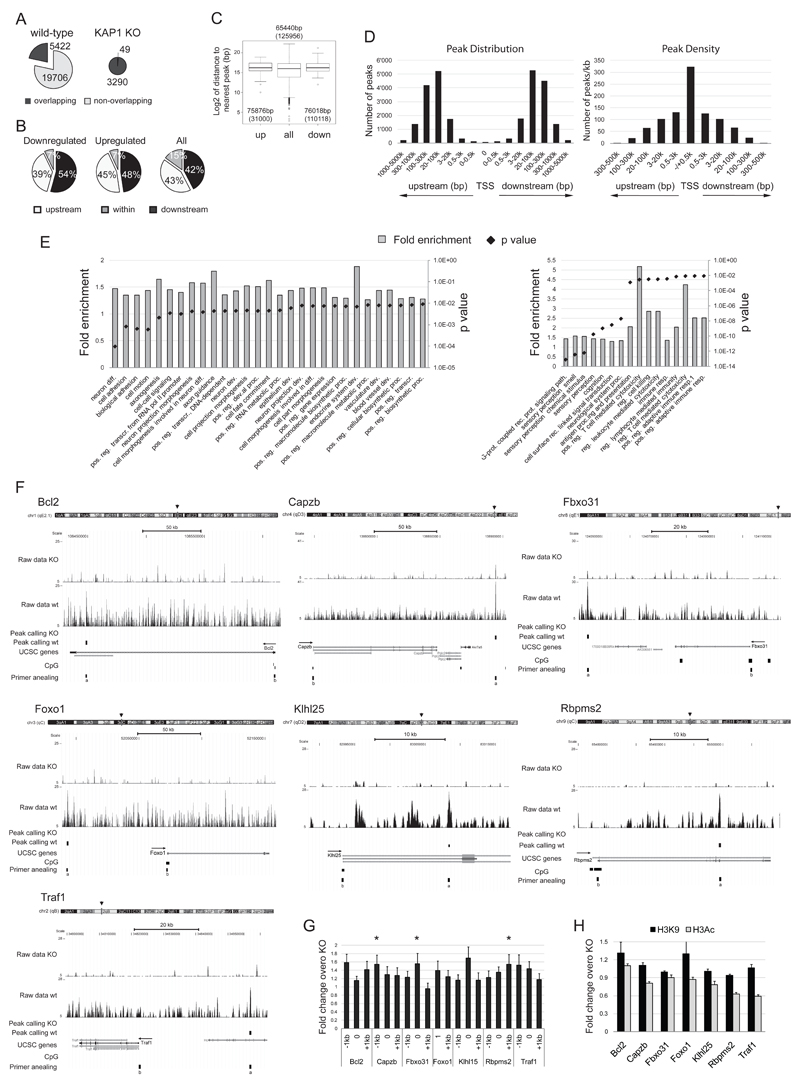

In order to discriminate between direct and indirect KAP1 target genes in T cells, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) on thymocytes harvested from wild type and knockout mice using an antibody raised against the RBCC domain of KAP1 [22]. We subjected the immunoprecipitates to deep sequencing and, after mapping the reads, used the ChIP-Seq Analysis Server (http://ccg.vital-it.ch/chipseq/) to identify significant hits. We obtained 25,128 and 3,339 peaks in wild type and KAP1-deleted samples, respectively. These numbers appear comparable to two recent KAP1 ChIP studies, where 7,000 target genes and 3,331 target promoters were identified by ChIP-chip in human NTERA2 and murine embryonic stem cells, respectively [45–46]. When we intersected the wild type and knockout lists, we found that about 25% (5422) of the wild type peaks overlapped with at least one peak in the knockout list, while almost all the knockout peaks (3290) overlapped with at least one peak in the wild type list (Fig. 4A) (overlapping was set in a window of +/-1kb from each peak). This, coupled with the observed residual KAP1 level of about 30% in the KAP1-depleted samples compared to wild type (data not shown, see also Fig. 1A and S2), indicated that most of the peaks found in the wild type sample were bona fide KAP1 binding sites and that the peaks found in the KAP1-deleted sample were most likely due to the residual protein rather than non-specific binding of the antibody.

Figure 4. KAP1 binding sites in T cells.

Chromatin from wild type and KAP1-deficient thymocytes was immunoprecipitated with a KAP1-specific antibody and captured DNA was sequenced (A-F) or analyzed by Q-PCR (G). A) KAP1 binding sites identified in wild type (left) and KAP1-deficient (KAP1 KO; right) thymocytes. Overlapping: number of wt (left) or KO (right) sites overlapping with at least 1 site identified in the KO (left) or wt (right) sample. The window set for the overlapping of each binding site is ± 1kb. B-C) Intersection of the list of KAP1 binding sites and the widest list of dysregulated genes (no cutoff, p<0.01; see Fig. 3). B) Proportions of binding sites found upstream, downstream and within the transcribed region of genes in the indicated lists are shown. p>0.05 by modified Fischer’s exact test. C) Median (interquartile range) of the distance (expressed as log2 of base pairs) from each gene to the nearest binding site in the indicated lists of genes. p value by Benjamini-Hochberg corrected Wilcoxon rank sum test. D) Distribution and density of KAP1 binding sites relative to TSS of all annotated genes. Number of peaks (left) and number of peaks/kilobase (right) found at the TSS (set at 0) and at the indicated distances upstream and downstream of it. E) Gene Ontology biological process classes of genes enriched in the list of nearest genes to KAP1 binding sites found in wt thymocytes. All genes (left panel) or genes with a peak closer than 20 kb (right panel) are shown as fold enrichment over background and p values. 1based on somatic recombination of immune receptors built from immunoglobulin superfamily domains, reg.=regulation, path.=pathway, pos.=positive, resp.=response, diff.=differentiation, rec.=receptor, dev.=development, proc.=process, transcr.=transcription. F) Seven genomic loci of upregulated genes are depicted together with ChIP-seq raw data (wt and KO) and binding sites as found in wt (peak calling wt) and KO (peak calling KO). For each locus, chromosome position (arrowhead), scale, UCSC based transcripts, CpG islands (suggestive of promoter regions) and position of PCR primers used for validation in G) (a) and H) (b) are depicted. Arrows indicate sense of transcription. G and H) Wild- type and KO thymocyte-derived chromatin was immunoprecipitated by KAP1 Ab (G) or H3K9me3 and H3Ac Abs (H) and Q-PCR was performed with primers amplifying the region depicted as a in F) (0), 1kb upstream (-1kb) and 1kb downstream (+1kb) for G) and as b in F) for H). Enrichment of IP samples is expressed as total input fraction normalized on the KO signal (Fold change over KO). Average of fold change over KO in the most stable control gene (GAPDH or Ccnd2) was set at 1. Average + SEM are shown. n=5; *p=0.0301 by one-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

We then intersected the list of binding sites with the list of genes found to be dysregulated by microarray. When we evaluated the distribution of the binding sites relative to transcribed regions, we found it not to be significantly different in dysregulated genes when compared to all annotated genes (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the median distance from transcribed region or transcriptional start site (TSS) to the nearest peak was not different in the list of dysregulated genes when compared to the list of all annotated genes (Fig. 4C and data not shown). This indicated that proximity of a KAP1 binding site does not allow one to predict reliably the impact of KAP1 and knockout thereof on expression of a given gene. We then investigated the distribution of KAP1 binding sites relative to the TSS of genes. We found that almost 20% of the peaks fell within 20kb from a TSS (Fig. 4D). This is of interest because we previously demonstrated that repressive marks can easily spread over such a distance starting from a KAP1 docking site [47]. That 20% of peaks be close to a TSS is significantly different from a random distribution, which would predict no more than 0.001% (20 out of 2x106, which is the approximate lengh of the genome in kb depleted of repeated sequences [48]) (p<0.0001 by Fischer’s exact test). Also, we found almost half of the peaks between 20 and 100kb from a TSS, which is very similar to recent observations in human cell lines [49]. Still, these data could be misleading because of a comparison in peak number between genomic regions with very different length (few versus tens/hundreds kb at the TSS versus more distant regions). We thus normalize the number of peaks falling in each region for the length of the region and calculated the density of peaks per kilobase. As shown in Fig. 4D, the higher density of peaks was found around the TSS, with about 1% of all the peaks falling in a window of +/-0.5kb from it. This percentage was significantly enriched over a random distribution in the genome, which would be 0.0005% (1 out of 2x106) (p<0.0001 by Fischer’s exact test) and supported the role of KAP1 in transcriptional regulation. Unfortunately, we could not perform the same distribution/density analysis for the list of dysregulated genes, due to a too low number of genes.

Next, we performed a peak-centric analysis and mapped the list of closest genes to KAP1 binding sites. When we used the full list of nearest genes to interrogate the DAVID bioinformatic database [40–41], we found the positive regulation of transcription from RNA Pol II promoter, cell adhesion, cell motion and cell-cell signaling GO classes very strongly enriched, confirming the role of KAP1 in regulating transcription on one hand and on the other its role in regulating cell homeostasis and migration pathways (Fig. 4E). Alongside these classes, we found genes involved in neuronal differentiation as the most enriched class. This might sound unexpected, but it was consistent with several dysregulated neuronal receptor encoding genes found in KAP1 knockout thymocytes, with the Vomeronasal receptor V1rd6 ranking as the most upregulated gene (9 fold upregulation as assessed by microarray; Table S1). When we restricted the analysis to genes found in a 20 kb window from peaks, together with neuronal classes we also observed G-protein coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, cell surface receptor linked signal transduction, and T lymphocytes and immune system related classes significantly enriched, further indicating a role of KAP1 in these pathways.

We next focused on some of the genes fully validated as upregulated upon KAP1 removal (see Fig. 3C). We assessed the position of the nearest peak relative to the genes of interest and designed primers spanning +/- 1kb from the predicted KAP1 binding (Fig. 4F). We subjected wild type- and KAP1 knockout-derived ChIP material to Q-PCR using specific and control primers and confirmed an enrichment of KAP1 binding in the wild type over knockout samples at all the tested loci, with Capzb, Fbxo31 and Rbpsm2 nearby sequences reaching statistical significance over unbound control regions (Fig. 4G). To further assess KAP1 direct role in regulating transcription of the analyzed genes, we evaluated chromatin status of their promoters in wild type and KAP1-deleted thymocytes. We performed ChIP-Q-PCR to examine H3K9me3, a heterochromatin mark typically associated with KAP1 activity [21, 50], and histone 3 acetylation (H3Ac), a mark of active transcription. We observed an enrichment of H3K9me3 and a depletion of H3Ac in wild type compared with KAP1-deleted cells for most of the tested promoters (Fig. 4H). This strongly suggests that expression of the tested genes was directly regulated by KAP1.

Since KAP1 has been shown to bind and, in some cases, control expression of at least one KRAB-ZFP cluster in human cells, we finally looked at KAP1 binding to KRAB-ZFP clusters conserved among mammals [45, 47, 51–52]. Very interestingly, in the KRAB-ZFP cluster located on chromosome 7qA3, we observed binding of KAP1 mainly to the last exon of the genes (Fig. S3), exactly at the same position as previously documented on human chromosome 19q13.4 [51]. This suggests that, despite the divergent evolution between mouse and human KRAB-ZFP, this type of regulatory feature has been conserved.

Altogether, these findings strongly support a direct role of KAP1 in regulating a subset of genes playing a role in survival/apoptosis, cytoskeleton organization and signal transduction in T cells. Dysregulation of these genes may be at the basis of the defects observed upon KAP1 removal.

KRAB-ZFP landscape in T cells

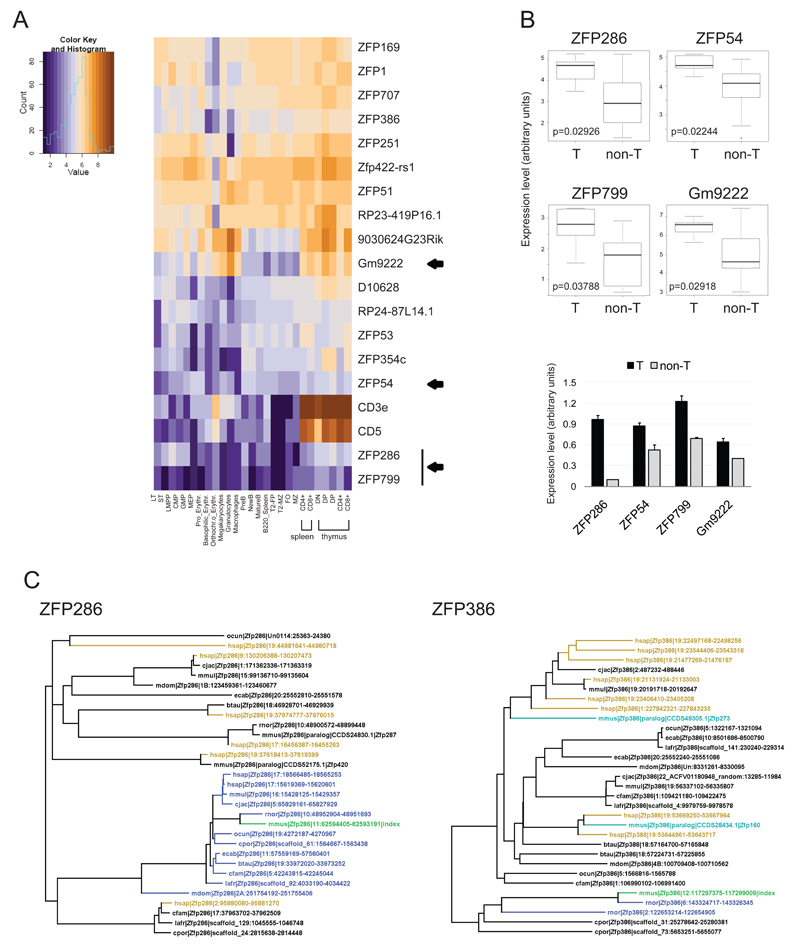

Since KAP1 was predicted to exert at least some of the above effects through the recognition of specific DNA sequences by KRAB-ZFPs, we sought to determine which members of this large family of regulators were expressed in various T lymphoid cells. For this, we quantified transcripts from 304 murine KRAB-ZFPs and 25 control genes by using a custom probe-set (282 probes) for the NanoString nCounter platform [53] in several sorted hematopoietic populations (for a complete list of all tested hematopoietic populations and staining strategies used for their isolation see supplementary methods). This recently developed technique has been extensively validated by several groups, including ours (data not shown and [54–56]). We then compared the expression level of each KRAB-ZFP in the T lineage with that measured in other hematopoietic cells. The results revealed that a rather small number of KRAB-ZFP genes were differentially expressed in T lymphoid cells. Indeed, only 17 and 11 KRAB-ZFPs were significantly more and less expressed in T cells, respectively (Fig. 5A and S3), which was confirmed by Q-PCR (Fig. 5B). Of note, ZFP51, ZFP53, ZFP54 were found to be differentially more expressed in the T lineage while ZFP52 was differentially more expressed in B cells (Fig. S4 and Santoni de Sio et al., submitted). Since these 4 genes are adjacent on the same cluster, it suggests independent regulation of KRAB-ZFP paralogs.

Figure 5. KRAB-ZFP map in T cells.

A) Heat map of KRAB-ZFP (and control genes) significantly higher expressed in T cells than in other hematopoietic lineages, as assessed by NanoString nCounter direct RNA quantification. For the staining strategy used to sort the different populations see supplementary methods. Arrowheads indicate KRAB-ZFP analyzed in panel B. B) Upper panels, median levels of expression of the indicated KRAB-ZFP in T cells (T) and the other analyzed hematopoietic cells (non-B) as assessed by Nanostring. p values by Benjamini-Hochberg corrected Wilcoxon rank sum test. Lower panel, expression levels of the depicted KRAB-ZFP in thymocytes (T) and B-enriched splenocytes (non-T) as assessed by Q-PCR analysis and expressed as average + SEM; n=3. C) Phylogenetic trees of the depicted KRAB-ZFP, based on ZF exon sequence alignment. Left panel, representative of KRAB-ZFP with human ortholog, right panel representative of KRAB-ZFP with rat ortholog. Each protein is defined by the genome: mouse=mmus, human=hsap, macaque=mmul, marmoset=cjac, cow=btau, dog=cfam, horse=ecab, rat=rnor, guinea pig=cpor, rabbit=ocun, elephant=lafr, opossum=mdom | query protein | contig and position (contig.start-end). Query protein is depicted in green and tagged as index. Blue: 1:1 orthologs, aqua: closest rodent paralogs, mustard: closest human genome matches.

We then investigated the conservation of KRAB-ZFP differentially more expressed in T cells by aligning their ZF exon sequences with several tetrapod genomes. KRAB-ZFPs are thought to have undergone divergent evolution in mice and humans [57–58], as underlined by the small number of mouse proteins having a human homolog (about 25%). Unexpectedly, for almost half of the KRAB-ZFP differentially expressed in T cells we found a human homolog (Fig. 5C and Fig. S4), indicating that these proteins have been conserved during evolution, which suggests that they play important roles. This seemed to be further supported by the fact that all the remaining KRAB-ZFP highly expressed in T cells but two had a rat homolog (Fig. 5C and Fig. S4).

Discussion

In the present work, we explored the impact of KRAB/KAP1-mediated epigenetic regulation on T cell biology. Through the study of T lymphoid KAP1 knockout mice, we found that KAP1 condition T cell development and homeostasis. KAP1 deletion resulted in abnormal expansions of the T lymphoid compartment in both the thymus and the periphery, an effect most obvious in competitive transplant experiments. This phenotype possibly originated in altered selection in the thymus and/or dysregulation of trafficking and/or survival/apoptosis pathways. Defective thymic selection might be due to altered TCR signaling threshold and might lead to the presence of non-functional and/or autoreactive T cells in the periphery. Whilst we did not specifically search for the presence of autoreactive clones in our mice, our in vitro experiments unveiled improper responses to TCR engagement in both their CD4+ and CD8+ cells, in particular upon sub-optimal stimulation. Since KAP1-deleted CD8+ could be efficiently primed by a viral challenge in vivo, KAP1 regulation appears to tune the strength of TCR-induced signal transduction, rather than to be essential for its triggering. Consistently, genes encoding for molecules involved in the Ras/MAPK and NF-κB pathways were dysregulated in KAP1-deleted T cells (see Table S1). However, since most of these genes were downregulated, they probably are indirect targets of KAP1, typically considered as a corepressor. In contrast, a number of genes encoding for molecules that control T cell activation and differentiation by counteracting TCR-induced signaling were upregulated, among which two appear of particular interest. The first is Tgfbr2, whose dysregulation may be relevant in light of the essential role of TGF signaling pathway in maintaining T cell compartment homeostasis [59]. The second is Traf1, which encodes for the intracellular adaptor of TNFR family members and acts downstream of the TCR along several pathways in T cells [60]. The Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 gene was also found dysregulated in Kap1-deleted thymocytes. This sounds of great interest considering the major role played by this molecule in the survival and homeostasis of mature thymocytes by regulating Klf2 and Il7rα gene expression [61][62].

In both the list of genes dysregulated upon KAP1 removal and that of genes closest to KAP1 binding sites, most of the significantly enriched biological processes are related to cytoskeleton/motility regulation pathways (see 3B and 4E). This strongly suggests a role for KAP1 in regulating these events, a point of high interest owing to the well-known role of cytoskeleton rearrangement in the formation of immunological synapses and in lymphocyte trafficking. Among genes belonging to this class, those encoding for the F-actin capping protein Capzb and the G-coupled receptors Gpr23 and Gpr174 were upregulated upon KAP1 removal. Gpr23 (also known as LPA4) belongs to the same family of G-coupled receptors of bioactive lipid as S1P receptors, whose member S1P1 is required for thymocytes trafficking [44]. Although a function for LPA4 in T cell has not been assessed, its negative role in cell motility resembles the action of S1P2 on S1P1 [42]. This, together with its predominant expression in lymphoid organs, suggests that its deregulation plays a role in the phenotype of T lymphoid KAP1 KO mice [63]. Supporting a model whereby survival/apoptosis were imbalanced in these animals is the upregulation of the anti-apoptotic factors Bcl2 and Bcl2l13, the DNA damage response/cell-cycle checkpoint regulator Fbxo31 and the oncosuppressor Glipr1 (also known as RTVP-1). ChiP-seq and ChIP-PCR analyses indicate that KAP1 binds nearby Bcl2, Capzb, Fbxo31, Foxo1 Klhl25, Rbpms2 and Traf1, and that this correlates with KAP1-dependent chromatin modifications at their promoters, strongly suggesting that they are under the direct influence of the master regulator. We thus conclude that, in the T cell compartment, KAP1controls the expression of a subset of genes involved in cytoskeletal rearrangement, survival/apoptosis and signaling, the dysregulation of which explains the phenotype of T lymphoid KAP1 knockout mice.

By KAP1 ChIP-seq analysis, we identified about 25,000 peaks in wild type thymocytes. Among them, less that 25% overlapped with peaks found in KAP1-deleted samples. This strongly suggests that the most of the called peaks represented bona fide KAP1 binding sites. Although the majority of these binding sites were found far away from transcriptional start sites, their relative density was significantly higher in the proximity of this genomic feature, further supporting a role for KAP1 in gene regulation. By performing a gene ontology analysis we find as the most enriched in the list of genes closest to KAP1 binding sites those involved in neuron differentiation. This correlated with the upregulation of several olfactory and pheromone receptors in KAP1-deleted thymocytes (see Table S1). Other unrelated differentiation pathways were also strongly represented amongst genes closest to KAP1 binding sites, such as epithelial, endocrine and vascular development (see Fig. 4E). Although the biological significance of this observation still needs to be assessed, these findings are reminiscent of the role of KAP1 in embryonic stem cells, where it silences genes involved in differentiation [46] and are consistent with a role for KAP1 in maintaining cell identity.

We also observed the binding of KAP1 to some KRAB-ZFP gene clusters, and in particular to the last exon of some KRAB-ZFP genes on chromosome 7qA3. This mouse genomic region is synthenic of human chromosome 19q13, where binding of KAP1 to the last exon of KRAB-ZFP genes has been documented [45, 47, 51–52]. Despite the known evolutionary divergence between mouse and human KRAB-ZFPs [64], this finding indicates a remarkable level of regulatory conservation during evolution. Consistent with this view, the few KRAB-ZFP genes more differentially expressed in T cells constitute a subgroup with a much higher rate of mouse-human orthologs than for the rest of this gene family, strongly suggesting that they play important and evolutionary conserved roles. On the other hand, among the non-conserved KRAB-ZFPs highly expressed in T cells we identified a cluster that is differentially regulated at the single gene level (ZFP51-54 cluster; see Fig. 5, S4 and Santoni de Sio et al., submitted). These findings support a model whereby specification went on after duplication during the evolution of KRAB-ZFP genes [65], illustrating the complexity of selective forces at play in this process.

Altogether, this work demonstrates that KRAB/KAP1-mediated epigenetic regulation has a significant impact on T cell development and homeostasis. Because the rapidly evolving KRAB-ZFP gene family exhibits significant polymorphism in humans, it would be interesting to ask whether nucleotide substitutions in its T cell-expressed members might underlie inter-individual differences in T cell-based immune responses.

Methods

Mice

Generation and genotyping of mice with a floxable KAP1 allele (KAP1flox; TiflβL3/L3), the CD4-Cre and the cre-reporter stopfloxYFP mouse strains have been described previously [29, 37–38]. CD4-Cre/KAP1flox and CD4-Cre/KAP1flox/stopfloxYFP mice were generated in a mix C57/bl6-129sv background. The offspring resulting from all the generated strains was born at expected rate. All animal experiments were approved by the local veterinary office and carried out in accordance with the European Community Council Directive (86/609/EEC) for care and use of laboratory animals.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

At the moment of sacrifice, we harvested blood, lymphnodes, spleen and thymus. Erythrocytes were lysed by Ammonium Chloride solution (StemCell Technologies). The following antibodies were used to label single cell suspensions: eFluor450- or PE-Cy5-coniugated anti-mouse CD3e, PE-Cy7- or FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4, PE-Cy7- or APC-efluor780-conjugated anti-mouse/CD8a, PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD25, biotin-conjugated anti-mouse TCRβ and TCRγδ, and APC or APC-Cy7-conjugated streptavidin (all from eBiosciences). Cells were analyzed by Dako CyAn ADP cytometer (Beckman-Coulter) or sorted by FACSAria II (Becton-Dickinson). About 300000 events falling in the physical parameters gate were acquired. See text and supplementary methods for staining strategies.

Small scale DNA, RNA and protein analysis

In vitro assays

CD4+ and CD8+ spleenocytes purified by Dynabeads® FlowComp™ Mouse CD4 followed by Dynabeads® FlowComp™ Mouse CD8 purification (both Invitrogen) following manufacturer instructions were stained or not with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and plated in flat-bottom 96 wells plate at a concentration of 106 cell/ml on anti-CD3 (3μg/ml) coated dishes in presence of anti-CD28 (1μg/ml) (both functional grade from eBiosciences) or on uncoated dishes in presence of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (both from SIGMA-Aldrich) at concentrations of 10ng/ml and 2ng/ml (1) or 2ng/ml and 0.4ng/ml (1/5 dilution). 3-4 days after plating supernatant was harvested and analyzed by Ready-set-go IFN ELISA kit (eBiosciences), following manufacturer instructions and cells were stained by PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD4 and APC-alexa780-conjugated anti-CD8 antibodies. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and percentage of undivided and divided cells was calculated on the basis of CFSE signal in the antibody-positive fractions. Unstained and stained unstimulated cells were used to set gates. At least 300000 events were acquired.

In vivo Immunization

8-12 weeks old mice were injected in the hind leg tibial muscle with 2.5×10^8 particles of recombinant adenoviral vector expressing GP33 glycoprotein of lymhochoriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and serum was collected two weeks after injection. Alternatively, mice were injected again with 2.5×10^8 particles particles 30 days after the first injection and serum collected 1 week later. After GP33 tetramer staining, percentage of CD8+GP33+ cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Vector details and tetramemer staining are described elsewhere [66].

MicroArray

RNA was extracted from 8-12 weeks old mouse thymocytes from 3 pairs of KO and littermate control C57/bl6-129sv mice generated from 3 different breeding couples by MirVana kit (Ambion) and treated with DNAse (Turbo DNA free kit, Ambion), following manufacturer instructions. After quality control for RNA integrity by capillary electrophoresis on Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, 100 ng of RNA was amplified and labeled using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification kit (Ambion). cRNA quality was assessed by capillary electrophoresis on Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Hybridization on Mouse WG 6 v2 expression arrays (Illumina) was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For analysis see supplementary methods.

ChIP-sequencing and ChIP-PCR

8-12 weeks old mouse thymocytes from C57/bl6-129sv mice were purified by Ficoll-Paque (GeLifesciences). 10^7 cells/sample were crosslinked by 1% formaldehyde and sonicated by Branson sonicator (8 cycles, 30sec/cycle). Chromatin was immunoprecipitated by using an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against KAP1 amino acids 20–418 (RBCC) (Schultz DC Gen Dev 2001, kindly provided by Dr. Rauscher). Detailed protocol for Chromatin immunoprecipitation is described elsewhere [67]. After de-crosslinking of both IP and total input, DNA was quantified with the Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) and 10 ng were used to prepare libraries for sequencing, following the ChIP Seq library preparation protocol (including End Repair for blunted end fragments, addition of “A” base to the 3’ end and ligation of adapters to DNA fragments (kit IP-102-1001). Ligation products were then purified on 2% E Gels Size Select (Invitrogen, fragments of 200 bp recovered), followed by enrichment of DNA fragments by PCR (18 cycles). No more than two libraries were loaded per gel to avoid cross contamination. Libraries were purified on AMP XP beads (Agencourt), quantified with Qubit fluorometer and size distribution determined on the Agilent Bioanalyzer (High Sensitivity DNA chip). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx with each library sequenced in a 38 bases single read run. For ChIP-seq analysis see supplementary methods. For ChIP-PCR analysis, after de-crosslinking same amount of IP and total input was used to perform Q-PCR. For KAP1, the same Ab used for sequencing was used. For histone marks ChIP 5 μg/reaction of H3K9me3 polyclonal Abs (H3K9me3either Abcam or Diagenode) and the rabbit polyclonal H3Ac (Millipore) were used. Specific primers used are listed in supplementary methods.

Direct RNA quantification by NanoString nCounter

To generate a comprehensive catalogue of KRAB-ZFP genes in the mouse genome, the Biomart database (http://www.biomart.org/, Mus musculus genes NCBIM37 dataset) was interrogated using as filters the Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) and the Prosite (http://www.expasy.ch/prosite/) KRAB domain IDs (PF01352 and PS50805 respectively). In this way, a list of 343 unique mouse KRAB-containing genes (mainly C2H2 KRAB-ZFPs) was identified. This list was used to generate a custom probe-set for the NanoString nCounter platform [53] for gene expression analysis. 282 probes identifying 329 genes (304 KRAB-ZFP and 25 controls) were designed; sequences can be obtained upon request. For details on NANostring analysis and KRAB-ZFP evolutionary analysis see supplementary methods.

Statistical analysis

We used non parametric tests for experiment with n<100. When the comparison was between two groups, we used the Mann-Whitney test. For correlation analyses, Spearman correlation test was used.

As contingency test, modified Fischer’s exact test was used. Unless specified, two-tailed tests were used. For statistical analysis of high throughput data see related paragraphs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Fabio Aloisio for histological analysis, Sonia Verp for technical help, Anna Groner, Helen Rowe and Corinne Schär for fruitful discussion, Giovanna Ambrosini, Jacques Rougemont, Patrick Descombes and the Genomics Platform of NCCR "Frontiers in Genetics” for help in high-throughput analyses. Jessica Dessimoz and the EPFL Histology Facility, and Miguel Garcia and the EPFL Flow Cytometry Core Facility. Part of the computations was performed on the Vital-IT facility www.vital-it.ch of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the European Research Council and the Strauss Foundation to DT.

Bibliography

- 1.Egger G, et al. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature. 2004;429(6990):457–63. doi: 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urdinguio RG, Sanchez-Mut JV, Esteller M. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological diseases: genes, syndromes, and therapies. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1056–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng J, Fan G. The role of DNA methylation in the central nervous system and neuropsychiatric disorders. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;89:67–84. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)89004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smale ST, Fisher AG. Chromatin structure and gene regulation in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:427–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kioussis D, Ellmeier W. Chromatin and CD4, CD8A and CD8B gene expression during thymic differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(12):909–19. doi: 10.1038/nri952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su RC, et al. Dynamic assembly of silent chromatin during thymocyte maturation. Nat Genet. 2004;36(5):502–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kioussis D, Georgopoulos K. Epigenetic flexibility underlying lineage choices in the adaptive immune system. Science. 2007;317(5838):620–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1143777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlenner SM, Rodewald HR. Early T cell development and the pitfalls of potential. Trends Immunol. 2010;31(8):303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maillard I, Fang T, Pear WS. Regulation of lymphoid development, differentiation, and function by the Notch pathway. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:945–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamasaki S, et al. Mechanistic basis of pre-T cell receptor-mediated autonomous signaling critical for thymocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(1):67–75. doi: 10.1038/ni1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starr TK, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Bosselut R. CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation: Thpok-ing into the nucleus. J Immunol. 2009;183(5):2903–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins A, Littman DR, Taniuchi I. RUNX proteins in transcription factor networks that regulate T-cell lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(2):106–15. doi: 10.1038/nri2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson CM, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 2006;442(7100):299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, et al. Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity. 1999;10(3):323–32. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misslitz A, et al. Thymic T cell development and progenitor localization depend on CCR7. J Exp Med. 2004;200(4):481–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi YI, et al. PlexinD1 glycoprotein controls migration of positively selected thymocytes into the medulla. Immunity. 2008;29(6):888–98. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakaguchi S, et al. The zinc-finger protein MAZR is part of the transcription factor network that controls the CD4 versus CD8 lineage fate of double-positive thymocytes. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(5):442–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuddapah S, Barski A, Zhao K. Epigenomics of T cell activation, differentiation, and memory. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(3):341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen AL, et al. Interaction with members of the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family and histone deacetylation are differentially involved in transcriptional silencing by members of the TIF1 family. EMBO J. 1999;18(22):6385–95. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sripathy SP, Stevens J, Schultz DC. The KAP1 corepressor functions to coordinate the assembly of de novo HP1-demarcated microenvironments of heterochromatin required for KRAB zinc finger protein-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(22):8623–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00487-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultz DC, Friedman JR, Rauscher FJ., 3rd Targeting histone deacetylase complexes via KRAB-zinc finger proteins: the PHD and bromodomains of KAP-1 form a cooperative unit that recruits a novel isoform of the Mi-2alpha subunit of NuRD. Genes Dev. 2001;15(4):428–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.869501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schultz DC, et al. SETDB1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 2002;16(8):919–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.973302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas JH, Emerson RO. Evolution of C2H2-zinc finger genes revisited. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emerson RO, Thomas JH. Adaptive evolution in zinc finger transcription factors. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(1):e1000325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman JR, et al. KAP-1, a novel corepressor for the highly conserved KRAB repression domain. Genes Dev. 1996;10(16):2067–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moosmann P, et al. Transcriptional repression by RING finger protein TIF1 beta that interacts with the KRAB repressor domain of KOX1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24(24):4859–67. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.4859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abrink M, et al. Conserved interaction between distinct Kruppel-associated box domains and the transcriptional intermediary factor 1 beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(4):1422–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041616998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cammas F, et al. Mice lacking the transcriptional corepressor TIF1beta are defective in early postimplantation development. Development. 2000;127(13):2955–63. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.13.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ziv Y, et al. Chromatin relaxation in response to DNA double-strand breaks is modulated by a novel ATM- and KAP-1 dependent pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(8):870–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf D, Goff SP. TRIM28 mediates primer binding site-targeted silencing of murine leukemia virus in embryonic cells. Cell. 2007;131(1):46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakobsson J, et al. KAP1-mediated epigenetic repression in the forebrain modulates behavioral vulnerability to stress. Neuron. 2008;60(5):818–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowe HM, et al. KAP1 controls endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2010;463(7278):237–40. doi: 10.1038/nature08674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackay DJ, et al. Hypomethylation of multiple imprinted loci in individuals with transient neonatal diabetes is associated with mutations in ZFP57. Nat Genet. 2008;40(8):949–51. doi: 10.1038/ng.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin JH, et al. PARIS (ZNF746) Repression of PGC-1alpha Contributes to Neurodegeneration in Parkinson's Disease. Cell. 2011;144(5):689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng L, et al. Sequence-specific transcriptional corepressor function for BRCA1 through a novel zinc finger protein, ZBRK1. Mol Cell. 2000;6(4):757–68. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfer A, et al. Inactivation of Notch 1 in immature thymocytes does not perturb CD4 or CD8T cell development. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(3):235–41. doi: 10.1038/85294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srinivas S, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jhunjhunwala S, et al. Chromatin architecture and the generation of antigen receptor diversity. Cell. 2009;138(3):435–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dennis G, Jr, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4(5):P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee Z, et al. Role of LPA4/p2y9/GPR23 in negative regulation of cell motility. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(12):5435–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugimoto N, et al. Inhibitory and stimulatory regulation of Rac and cell motility by the G12/13-Rho and Gi pathways integrated downstream of a single G protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor isoform. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(5):1534–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1534-1545.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matloubian M, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427(6972):355–60. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Geen H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of KAP1 binding suggests autoregulation of KRAB-ZNFs. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(6):e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu G, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies a new transcriptional module required for self-renewal. Genes Dev. 2009;23(7):837–48. doi: 10.1101/gad.1769609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Groner AC, et al. KRAB-zinc finger proteins and KAP1 can mediate long-range transcriptional repression through heterochromatin spreading. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(3):e1000869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kazazian HH., Jr Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science. 2004;303(5664):1626–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iyengar S, et al. Functional analysis of KAP1 genomic recruitment. Mol Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01331-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ivanov AV, et al. PHD domain-mediated E3 ligase activity directs intramolecular sumoylation of an adjacent bromodomain required for gene silencing. Mol Cell. 2007;28(5):823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blahnik KR, et al. Characterization of the contradictory chromatin signatures at the 3' exons of zinc finger genes. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel MJ, et al. Human heterochromatin proteins form large domains containing KRAB-ZNF genes. Genome Res. 2006;16(12):1493–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.5391806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geiss GK, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(3):317–25. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malkov VA, et al. Multiplexed measurements of gene signatures in different analytes using the Nanostring nCounter Assay System. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:80. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Payton JE, et al. High throughput digital quantification of mRNA abundance in primary human acute myeloid leukemia samples. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1714–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI38248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun Z, et al. Integrated Analysis of Gene Expression, CpG Island Methylation, and Gene Copy Number in Breast Cancer Cells by Deep Sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e17490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Looman C, et al. KRAB zinc finger proteins: an analysis of the molecular mechanisms governing their increase in numbers and complexity during evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(12):2118–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huntley S, et al. A comprehensive catalog of human KRAB-associated zinc finger genes: insights into the evolutionary history of a large family of transcriptional repressors. Genome Res. 2006;16(5):669–77. doi: 10.1101/gr.4842106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubtsov YP, Rudensky AY. TGFbeta signalling in control of T-cell-mediated self-reactivity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(6):443–53. doi: 10.1038/nri2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ha H, Han D, Choi Y. TRAF-mediated TNFR-family signaling. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2009;Chapter 11:Unit11 9D. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1109ds87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ouyang W, et al. An essential role of the Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 in control of T cell homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30(3):358–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kerdiles YM, et al. Foxo1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7 and interleukin 7 receptor. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(2):176–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanchez T, Hla T. Structural and functional characteristics of S1P receptors. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92(5):913–22. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shannon M, et al. Differential expansion of zinc-finger transcription factor loci in homologous human and mouse gene clusters. Genome Res. 2003;13(6A):1097–110. doi: 10.1101/gr.963903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nowick K, et al. Rapid sequence and expression divergence suggest selection for novel function in primate-specific KRAB-ZNF genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(11):2606–17. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flatz L, et al. Development of replication-defective lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus vectors for the induction of potent CD8+ T cell immunity. Nat Med. 2010;16(3):339–45. doi: 10.1038/nm.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barski A, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129(4):823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.