Abstract

To examine whether doses of melphalan higher than 200 mg/m2 improve response rates when used as conditioning before autologous transplant (ASCT) in myeloma (MM) patients.

Patients with MM, N= 131, were randomized to 200 mg/m2 (mel200) v. 280 mg/m2 (mel280) using amifostine pretreatment. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving ≥nCR.

No treatment-related deaths occurred in this study. Responses following ASCT were for mel200 v. mel280, respectively, ≥nCR 22% v. 39%, p=0.03, ≥PR 57% v. 74%, p= 0.04. The hazard of mortality was not statistically significantly different between groups (mel200 v. mel280; HR=1.15 (95% CI, 0.62 to 2.13, p=0.66)) nor was the rate of progression/mortality (HR=0.81 (0.52 to 1.27, p=0.36)). The estimated progression-free survival at 1 and 3 years was 83% and 46%, respectively, for mel200 and 78% and 54%, respectively, for mel280. Amifostine and mel280 were well tolerated, with no grade-4 regimen-related toxicities and only 1 grade-3 mucositis (none with mel200) and 3 grade-3 GI toxicities (2 in mel200). Hospitalization rates were more frequent in the mel280 group (59% v. 43%, p=0.08).

Mel280 resulted in a higher major response rate (CR+nCR)_ and should be evaluated in larger studies.

Introduction

High-dose chemotherapy followed by transfusion of autologous stem cells (ASCT) has become an important treatment option for suitable patients with multiple myeloma (MM). This is due to a series of prospective trials comparing ASCT as consolidation after conventional therapy induction demonstrating improved response rates, greater progression-free survivals and in some but not all studies, improved overall survival. (1–5) The dose of melphalan, 200 mg/m2 was established from early trials demonstrating unacceptable gastrointestinal toxicity at higher doses.(6) Single-agent high-dose melphalan has remained the standard regimen for patients with myeloma who undergo ASCT due to the paucity of trials comparing melphalan, 200 mg/m2 to other chemotherapy regimens or melphalan with added total body irradiation (TBI). A single comparison trial has shown that adding TBI to melphalan is inferior to melphalan 200 mg/m2 with respect to overall survival.(7)

The cytoprotective drug amifostine is approved by the FDA for preventing platinum-associated nephrotoxicity and xerostomia associated with head and neck irradiation. Retrospective and prospective trials of amifostine have shown a reduction in gastrointestinal toxicities caused by melphalan 200 mg/m2 when given prior to ASCT.(8, 9) In a phase 1 dose-escalation trial, amifostine was shown to protect patients from the gastrointestinal toxicities of melphalan given in doses as high as 280 mg/m2 followed by ASCT.(10) A phase 2 trial utilizing amifosine and a fixed dose of melphalan 280 mg/m2 followed by ASCT reported no serious gastrointestinal toxicities and a complete response (CR) rate of 55%.(11)

With this background we conducted a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial comparing melphalan 200 mg/m2 with melphalan 280 mg/m2 for patients with multiple myeloma who were candidates for ASCT. We hypothesized that the higher dose of melphalan could improve response rates with the potential to improve outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This prospective trial was designed to compare response rates after high-dose melphalan 200 mg/m2 or 280 mg/m2 used prior to ASCT in patients with multiple myeloma. The primary endpoint was the rate of near complete response (nCR) or better between the groups as defined by modified criteria reported by Blade.(12) nCR is defined as the absence of measurable monoclonal proteins by serum or urine electrophoresis but still detectable by immunofixation, less than 5% plasma cells by bone marrow histology, no new bone lesions or progression of existing lesion on skeletal survey and normal calcium. Secondary endpoints included overall response rates, grade 3–4 toxicities defined by NCI CTCAE v3.0, incidence and length of hospitalizations, overall and progression-free survival. Partial response after transplant required a 50% reduction in monoclonal protein from pre-transplant levels. Eligibility criteria included symptomatic multiple myeloma requiring therapy, measurable disease consisting of at least 0.2 g/dl monoclonal protein in serum or at least 200 mg Bence-Jones protein per 24 hours in urine, ECOG performance status of 2 or less, cardiac ejection fraction of at least 50%, CO2 diffusion capacity of at least 50%, total bilirubin <2 mg/dl, GGT <2.5 times upper limit of normal and an estimated or measured creatinine clearance of >60 ml/min. Patients with nonsecretory, serum light chain only and patients in ≥nCR were excluded. Specifically patients with a monoclonal protein of 0.1 g/dl or less or a Bence Jones protein level less than 200 mg were excluded. Patients who had received a prior ASCT were excluded.

Eligible patients who signed informed consent were randomized 1:1 centrally by the coordinating center in Seattle. Patients were stratified by a B2M of 5 or greater and by the presence of del13 detected by FISH or conventional cytogenetics. All patients received amifostine for cytoprotection prior to the high-dose melphalan. Amifostine was given 24 hours and again 30 minutes prior to high-dose melphalan at 740 mg/m2 by intravenous push over 3–5 minutes. Patients received hydration and premedication with ranitidine, dexamethasone, ondansetron and diphenhydramine. Melphalan 200 mg/m2 or 280 mg/m2 was given by intravenous infusion over 30 minutes as a single dose. Patients in both groups were encouraged to use ice chips before and for several hours after high-dose melphalan to reduce mucositis.(13) Cryopreserved peripheral blood stem cells were thawed and infused 2 days after melphalan per local institutional guidelines. Standard transfusion and antibiotic support measures were utilized at each Center. Engraftment of neutrophils was defined as the first of 2 consecutive days >5 × 108/l. Engraftment of platelets was the first of 7 consecutive days >20 × 109/l without transfusion. Between 70–100 days after ASCT, patients were restaged with a marrow aspiration, skeletal survey, calcium level, serum protein electrophoresis and 24-hour urine collection for quantitative Bence-Jones protein.

The study was designed to have 80% power to observe a statistically significant difference (at the two-sided significance level of 0.05) in the probabilities of ≥nCR, where the assumed-true probabilities of ≥nCR were 0.30 and 0.55 for mel200 and mel280, respectively. Probabilities of response, toxicity, and hospitalization were compared with the chi-square test, and OS and PFS were summarized using Kaplan-Meier estimates. The hazards of failure for both OS and PFS were compared using Cox regression. Duration of hospitalization was compared with the rank-sum test.

This trial (NCT00217438) opened for enrollment September 2005 and completed enrollment in June 2012. Patients were enrolled at 4 centers; The University of Washington, Seattle, the Veterans Administration Hospital, Seattle, the Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles and the James Wilmot Cancer Center in Rochester, NY. The protocol and consent forms were approved by local IRB’s at each participating center.

Results

Of 134 patients who consented to this study, 1 patient did not meet inclusion criteria and 2 declined to participate. A total of 131 patients were randomized which met pre-defined accrual, closing the study. Outcomes are reported by intention-to-treat once patients were randomized. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. They were well matched for age, gender, race and number of prior treatments. The median times from diagnosis to ASCT were 9.5 months in the mel280 group v. 9.0 months in the mel200 group. Table 2 includes additional information on timing of transplant, prior use of novel drugs for induction and details on maintenance therapy. The majority of patients, 77–79% received transplant as consolidation after 1–2 induction regimens. Almost all of the patients received induction therapy with one or more novel agents; more patients in the mel200 group received lenalinomide as part of their initial therapies. Less than half of the patients received maintenance therapy after ASCT; 43% in the Mel200 group v. 47% in the Mel280 group.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Melphalan 280 | Melphalan 200 | |

|---|---|---|

| n=66 | n=65 | |

| Age | 58 (42–70) | 55 (42–70) |

| Male/Female | 43/23 | 42/23 |

| Race C/B/A/H/NA# | 58/4/2/1/1 | 53/5/4/2/0 |

| Prior Regimens | 2 (1–8) | 2 (1–7) |

| Response prior to ASCT* Number ≥PR/<PR | 37/29 | 38/26 |

| B2M >5 Number | 5 | 3 |

| Adverse Cyto/FISH+ Number | 15 | 10 |

| ISS stage at diagnosis Number 1/2/3no data | 25/28/6/5 | 22/22/13/9 |

| Time from diagnosis to ASCT (mo) | 9.5 (3–78) | 9.0 (4–103) |

Caucasian/Black/Asian/Hispanic/Native American

Best response to induction therapy just prior to ASCT

hypodiploid cytogenetics or del13, FISH del13, 17p or 4;14.

Table 2.

Disease status at transplant and use of novel drugs for induction and maintenance

| Transplant Status | Mel200 N=65 | Mel280 N=66 |

|---|---|---|

| Upfront | 50 | 52 |

| Relapse | 15 | 14 |

| Induction Drugs* | 64 | 64 |

| lenalidomide | 38 | 24 |

| bortezomib | 40 | 41 |

| thalidomide | 24 | 27 |

| Maintenance# | 28 | 31 |

| lenalidomide | 21 | 22 |

| bortezomib | 3 | 4 |

| thalidomide | 2 | 3 |

| dexamethasone | 2 | 2 |

Number of patients receiving 1 or more novel drugs for induction

Number of patients receiving maintenance therapy

Toxicities from Amifostine Infusion

Infusional toxicities were generally manageable with hydration and premedication with ranitidine, dexamethasone, ondansetron and diphenhydramine. Grades 1–2 hypotension, nausea and flushing were common expected toxicities, except for the grade 3 hypotensive episode occurring in one patient withdrawn from study (this patient is analyzed as randomized, however). Among all patients randomized, toxicities are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Infusional toxicities after amifostine; N (%; 95% CI)

| Grades 1–2* | Melphalan | Melphalan |

|---|---|---|

| 280 (n=66) | 200 (n=65) | |

| Hypotension | 9 (14%; 5–22%) | 10 (15%; 7–24%) |

| Nausea | 18 (27%; 17–38%) | 15 (23%; 13–33%) |

| Flushing | 11 (17%; 8–26%) | 11 (17%; 8–26%) |

| Sneezing | 3 (5%; 0–10%) | 5 (8%; 1–14%) |

| Drowsiness | 2 (3%; 0–7%) | 3 (5%; 0–10%) |

Toxicities and hospitalization after Melphalan and ASCT

Patients who received mel280 tended to have more grades 2–3 mucositis (33% (95% CI, 22–45%) v. 12% (95% CI, 4–20%), p=0.004). There were also more grade 2–3 gastrointestinal toxicities in the mel280 group but the difference was not statistically significant (21% (95% CI, 11–31%) v. 12% (95% CI, 4–10%), p=0.17). Twenty-four of the 66 (36% (95% CI, 25–48%) mel280 patients had at least one grade 2–3 toxicity compared to 14 of 65 (22% (95% CI, 12–32%)) patients in the mel200 group, p=0.06. More patients were hospitalized who received mel280, although the frequency was not statistically significantly (59% (95% CI, 47–71%) v. 43% (95% CI, 31–55%), p=0.08) and there was a suggestion that the duration of hospitalization was longer in the mel280 group (median 6 days v. 0 days, p=0.02) Table 4.

Table 4.

Number (%; 95% CI) of Toxicities and Hospitalization after Melphalan, analyzed on a per-patient basis

| Melphalan 280 | Melphalan 200 | p-value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=66) | (n=65) | ||||||

| Grades | Gr1 | Gr2 | Gr3 | Gr1 | Gr2 | Gr3 | |

| Mucositis | 5 | 21 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 0 | |

| Grades 2–3 Mucositis | 22 (33%;22–45%) | 8 (12%;4–20%) | 0.004 | ||||

| GI | 10 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 6 | 2 | |

| Grades 2–3 GI | 14 (21%;11–31%) | 8 (12%;4–20%) | 0.17 | ||||

| Hepatic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Renal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Skin | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cardiac | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| CNS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bladder | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Any Grade 2–3 | 24 (36%;25–48%) | 14 (22%;12–32%) | 0.06 | ||||

| # Patients Hospitalized | 39 (59%) | 28 (43%) | 0.08 | ||||

| Median (range) | 6 (0–33) | 0 (0–23) | 0.02 | ||||

| Hospital days | |||||||

compares proportion of grade 2–3 toxicity between groups for listed toxicity

Engraftment

The Mel280 group had ANC engraftment slightly faster than Mel200 (median 14 days vs. 15 days; mean 14.0 days vs. 16.5 days), p=.006 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test). The time to platelet engraftment was similar (median 10 days both; mean 11.0 Mel200 vs. mean 11.6 Mel280), p=.44 (rank-sum)

Platelet requirements were a slightly higher in the Mel280 group (median 6 for both; mean 9.7 in Mel280 vs. mean 6.6 in Mel200), p=.03 (rank-sum test) RBC requirements were a bit higher in the Mel280 group but not statistically significantly higher (median 2 both; mean 2.3 in Mel280 vs. mean 2.0 in Mel200), p=.17 (rank-sum test)

No deaths occurred during the transplant and recovery phase in either group.

Response after ASCT

Among the group receiving mel280 26 of 66 patients achieved ≥nCR (39.4% (95% CI, 28.5–51.5%) compared to 14 of 65 patients receiving mel200 (22.2% (95% CI, 13.2–33.1%)), p=0.03. The overall response rates were 74.2% (95% CI, 62.5–83.3%) for mel280 v. 56.9% (95% CI, 44.8–68.2%) for mel200, p=0.04, Table 5.

Table 5.

Responses after Mel280 or Mel200

| Melphalan 280 | Melphalan 200 | |

|---|---|---|

| N=66 | N=65 | |

| CR | 8 | 7 |

| nCR | 18 | 7 |

| nCR + CR | 26 (39.4%) | 14 (21.5%) |

| PR | 23 | 22 |

| nCR + CR + PR | 49 (74.2%) | 37 (56.9%) |

| MR | 1 | 9 |

| SD | 14 | 16 |

| PD | 2 | 3 |

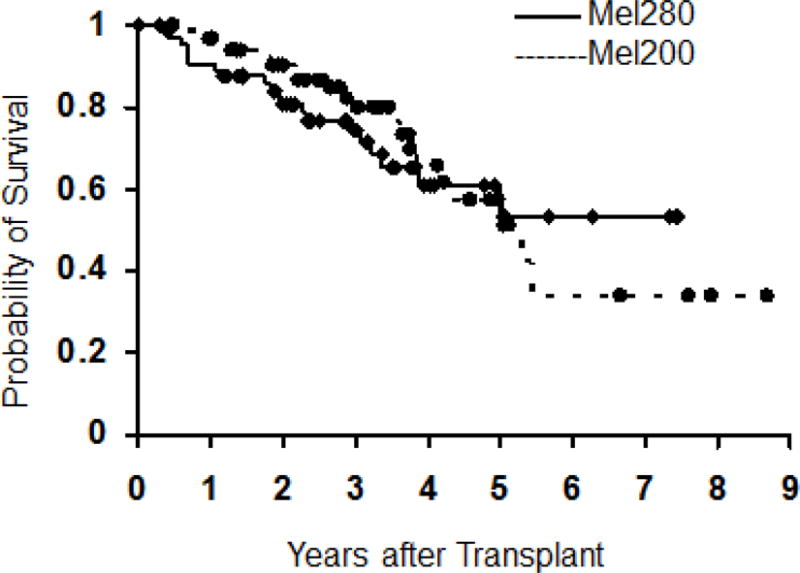

The median follow-up among survivors is 3.3 years (range 0.5–8.7) in the mel200 group and 3.0 years (range 0.3–8.2) in the mel280 group. The median progression-free survival is 2.7 years and 3.5 years, respectively, and the median overall survival is 5.3 years and 6.2 years, respectively. There were no statistically significant difference in the hazard rate for failure (death or relapse) between patients receiving mel200 v. mel280; HR=0.81 (95% CI 0.52–1.27, p=0.36) (figure 1). The hazard of overall mortality was similarly not statistically significantly different between patients receiving mel200 and mel280; HR=1.15 (95% CI 0.62–2.13, p=0.66).(figure 2).

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival between patients receiving mel200 and mel 280.

Figure 2.

Overall survival between patients receiving mel200 and mel280.

Discussion

High-dose melphalan followed by ASCT remains a standard of care for suitable patients with MM. This approach leads to improved response rates, progression-free and overall survival, but few if any patients are actually cured by ASCT. Despite several attempts there has been little progress in improving conditioning regimens for patients who are candidates for ASCT. One prospective trial comparing single-agent melphalan to melphalan plus total body irradiation observed similar progression-free survivals but superior overall survival for single-agent melphalan.(7) Retrospective studies have suggested that some regimens such as BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytosine arabinoside, melphalan) may improve outcomes when compared to patients with myeloma receiving single-agent melphalan but these have not been validated prospectively.(14) Other studies have examined adding myeloma-specific drugs such as bortezomib to high-dose melphalan.(15, 16) These studies suggest higher initial response rates but no long-term outcomes or randomized comparison trials have been reported.

The present study was based on phase 1–2 studies demonstrating that amifostine could protect patients from limiting gastrointestinal toxicities of melphalan at doses as high as 280 mg/m2.(17) These studies also suggested a continuing steep dose-response curve with melphalan. The current study validated the potential for dose-escalated melphalan 280 mg/m2 to improve responses. This 40% higher dose did result in a greater proportion of patients achieving a major response (nCR) and improved the ORR. We observed a higher nCR rate of 39.4% v. 21.5% after mel280 and a higher ORR in this group, 74.2% v. 56.9%.

While the improved responses did not improve PFS or OS, the study was neither designed nor powered to show statistically significant differences in PFS or OS. This outcome is not different from recently published randomized trials of initial therapy comparing bortezomib, dexamethasone (VD) with vincristine, adriamycin, dexamethasone (VAD).(18) Despite significantly higher rates of nCR and ORR with VD induction both before and after ASCT, there were no significant differences in PFS or OS. This trial enrolled 482 patients, 3 times the current study, but was still unable to discern differences in outcomes. A 470-patient trial of bortezomib. Thalidomide, dexamethasone (VTD) v.TD induction was able to show differences in major response rates and PFS but also was not able to show statistically significant survival differences.(19) Although maintenance was given to about 50% of the patients in this study, the proportions of patients who received maintenance in either arm of the study were similar and thus would not likely have influenced outcomes.

In order to measure the rates of major response the current study excluded patients who were already in CR or nCR prior to ASCT. This may have biased the study toward a group of patients with more resistant disease who in turn would tend to have shorter lengths of remission. There were more patients with grade 2–3 mucositis in the mel280 group but no statistically significant difference in grades 2–3 gastrointestinal. There were no observed episodes of grade 4 mucositis in this study and only one episode of grade 3 mucositis (in the mel280 arm). This appears to be considerably lower than reports of oral mucositis in other studies which have ranged from 21–46%.(20, 21) This is likely the result of the combined use of ice chips and amifostine. Such supportive care measures should be considered for all patients receiving high-dose melphalan. In a prior randomized trial, the use of amifostine significantly reduced the incidence of gastrointestinal toxicities including severe mucositis.(8) We did observe a longer length of hospitalization in the mel280 group. This did not result in more transplant-related deaths, however; in fact, there were no patients who died of complications of transplant in the entire study.

This trial has demonstrated that amifostine can limit the toxicities associated with melphalan given at 280 mg/m2. This higher dose of melphalan can result in improved response rates. Whether or not this approach can improve PFS or OS would require a much larger, prospective randomized trial.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by research funds supplied by Astra-Zeneca, R21 CA155911-01, and by P01 CA18029-28 both from NIH/NCI.

Footnotes

Previously Published at the 2012 ASH Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA December 2012

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosure

W.B. received research funding for this trial from Astra-Zeneca. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Attal M, Harousseau J-L, Stoppa A-M, Sotto J-J, Fuzibet J-G, Rossi J-F, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(2):91–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blade J, Rosinol L, Sureda A, Ribera JM, Diaz-Mediavilla J, Garcia-Larana J, et al. High-dose therapy intensification compared with continued standard chemotherapy in multiple myeloma patients responding to the initial chemotherapy: long-term results from a prospective randomized trial from the Spanish cooperative group PETHEMA. Blood. 2005 Dec 1;106(12):3755–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Owen RG, Bell SE, Hawkins K, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 8;348(19):1875–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlogie B, Kyle RA, Anderson KC, Greipp PR, Lazarus HM, Hurd DD, et al. Standard chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemoradiotherapy for multiple myeloma: final results of phase III US Intergroup Trial S9321 [erratum appears in J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jun 10;24(17):2687] J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 20;24(6):929–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fermand J-P, Ravaud P, Chevret S, Divine M, Leblond V, Belanger C, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: up-front or rescue treatment? Results of a multicenter sequential randomized clinical trial. Blood. 1998 Nov 1;92(9):3131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuels BL, Bitran JD. High-dose intravenous melphalan: a review (Review) J Clin Oncol. 1995 Jul;13(7):1786–99. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreau P, Facon T, Attal M, Hulin C, Michallet M, Maloisel F, et al. Comparison of 200 mg/m2 melphalan and 8 Gy total body irradiation plus 140 mg/m2 melphalan as conditioning regimens for peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: final analysis of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome 9502 randomized trial. Blood. 2002 Feb 1;99(3):731–5. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spencer A, Horvath N, Gibson J, Prince HM, Herrmann R, Bashford J, et al. Prospective randomised trial of amifostine cytoprotection in myeloma patients undergoing high-dose melphalan conditioned autologous stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005 May;35(10):971–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thieblemont C, Dumontet C, Saad H, Roch N, Bouafia F, Arnaud P, et al. Amifostine reduces mucosal damage after high-dose melphalan conditioning and autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation for patients with multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002 Dec;30(11):769–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philllips GL, Meisenberg B, Reece DE, Adams VR, Badros A, Brunner J, et al. Amifostine and autologous hematopoietic stem cell support of escalating-dose melphalan: a phase I study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004 Jul;10(7):473–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reece DE, Vesole D, Flomenberg N, Badros A, Filicko J, Herzig R, et al. Intensive therapy with high-dose melphalan (MEL) 280mg/m2 plus amifostine cytoprotection and ASCT as part of initial therapy in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002 Nov 16;100(Part 1 and 11):432a, #1672. Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bladé J, Samson D, Reece D, Apperley J, Björkstrand B, Gahrton G, et al. Criteria for evaluating disease response and progression in patients with multiple myeloma treated by high-dose therapy and haemopoietic stem cell transplantation. Myeloma Subcommittee of the EBMT. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplant. Br J Haematol. 1998 Sep;102(5):1115–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lilleby K, Garcia P, Gooley T, McDonnell P, Taber R, Holmberg L, et al. A prospective, randomized study of cryotherapy during administration of high-dose melphalan to decrease the severity and duration of oral mucositis in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:1031–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faber EAJ, Loberiza FR, Jr, Akhtari M, Bierman P, Bociek RG, Maness L, et al. A retrospective analysis comparing BEAM versus melphalan prior to first autologous peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cell transplant in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2011;118(21):#2040. Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roussel M, Moreau P, Huynh A, Mary JY, Danho C, Caillot D, et al. Bortezomib and high-dose melphalan as conditioning regimen before autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with de novo multiple myeloma: a phase 2 study of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM) Blood. 2010 Jan 7;115(1):32–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-229658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lonial S, Kaufman J, Tighiouart M, Nooka A, Langston AA, Heffner LT, et al. A phase I/II trial combining high-dose melphalan and autologous transplant with bortezomib for multiple myeloma: a dose- and schedule-finding study. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Oct 15;16(20):5079–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips GL, Meisenberg BR, Reece DE, Adams VR, Badros AZ, Brunner JL, et al. Activity of single-agent melphalan 220-300 mg/m2 with amifostine cytoprotection and autologous hematopoietic stem cell support in non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004 Apr;33(8):781–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harousseau JL, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H, Marit G, Caillot D, Mohty M, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the IFM 2005-01 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Oct 20;28(30):4621–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.9158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, Petrucci MT, Pantani L, Galli M, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study.[Erratum appears in Lancet. 2011 Nov 26;378(9806):1846] Lancet. 2010 Dec 18;376(9758):2075–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blijlevens N, Schwenkglenks M, Bacon P, D’Addio A, Einsele H, Maertens J, et al. Prospective oral mucositis audit: oral mucositis in patients receiving high-dose melphalan or BEAM conditioning chemotherapy–European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Mucositis Advisory Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Mar 20;26(9):1519–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grazziutti ML, Dong L, Miceli MH, Krishna SG, Kiwan E, Syed N, et al. Oral mucositis in myeloma patients undergoing melphalan-based autologous stem cell transplantation: incidence, risk factors and a severity predictive model. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006 Oct;38(7):501–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]