Abstract:

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) is a rare aggressive hematologic malignancy primarily found in adults, often carrying a poor prognosis. There are only 33 reported pediatric cases of BPDCN in the literature. Although standard treatment is not yet established for children, current literature recommends the use of high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)–type chemotherapy. Recent studies, however, have explored the benefits of combining chemotherapy with stem-cell transplantation. Here, the authors present 2 cases of pediatric BPDCN treated with different modalities. The first case is a 13-year-old girl who presented with a 3-month history of an initially asymptomatic firm nodule on her left shin. The second case is a 15-year-old boy who presented with a 4-month history of an enlarging subcutaneous nodule on the lower leg. Immunohistochemical staining of both patients was positive for markers consistent with BPDCN. The latter patient received ALL-type therapy alone, whereas the former received ALL-type chemotherapy and stem-cell transplantation. Since initial treatment, both patients remain disease-free. These cases contribute to the limited number of pediatric BPDCN cases, thus helping to advance our knowledge toward an optimal treatment protocol for clinical remission.

Key Words: blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, acute lymphoblastic leukemia-type chemotherapy, pediatrics, CD4, CD56, stem-cell transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) accounts for less than 1% of cutaneous lymphomas, typically presenting in the skin of older adults with rapid progression to systemic involvement and death within 1 year.1 Cases in children are exceedingly rare but seem to harbor a better prognosis. Here, we describe 2 cases of BPDCN in the pediatric population.

CASE 1

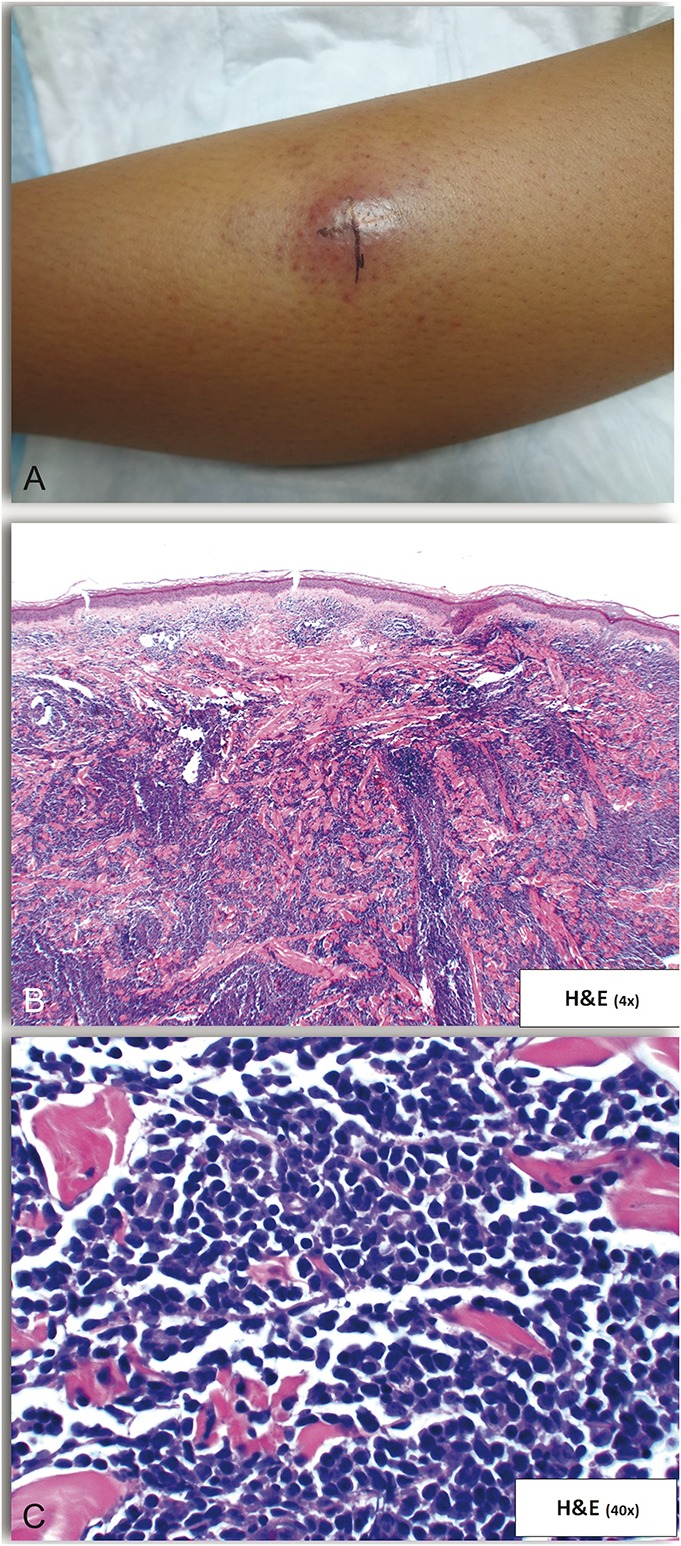

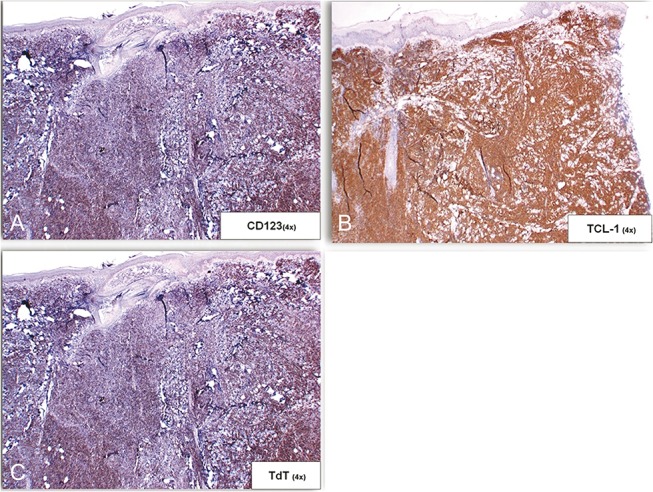

A previously healthy 13-year-old girl presented with a 3-month history of a persistent “bug bite” on the left anterior shin. The lesion began as an asymptomatic solitary red papule that grew into a firm nodule. On physical examination, there was a solitary 2.1 cm indurated red-brown nodule with smaller violaceous macules at the periphery (Fig. 1A). A punch biopsy revealed a pandermal infiltrate of monomorphic small- to medium-sized atypical lymphocytes, with an overlying Grenz zone present (Figs. 1B, C). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for CD4, CD56, CD123, TCL-1, and TdT (Figs. 2A–C) and negative for CD3, CD20, MPO, lysozyme, CD34, and CD117, supporting a diagnosis of BPDCN. Cytologic and flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood, bone marrow, and cerebrospinal fluid showed no neoplastic cell infiltration. The patient received chemotherapy after a lymphoblastic lymphoma-type induction protocol, which resulted in resolution of her cutaneous lesions. She subsequently underwent an allogeneic bone marrow transplant from an HLA-identical sibling. Eighteen months later, she remains in clinical remission.

FIGURE 1.

Examination and skin biopsy findings of Case 1. A, Solitary 2.1 cm indurated red-brown nodule with smaller violaceous macules at the periphery. B, Pandermal infiltrate of monomorphic small-to-medium sized atypical cells with an overlying Grenz zone. C, Higher magnification of (B).

FIGURE 2.

Immunohistochemical findings of biopsy from Case 1. A, B, and C, The neoplastic cells were positive for CD123 (A), TCL-1 (B), and TdT (C).

CASE 2

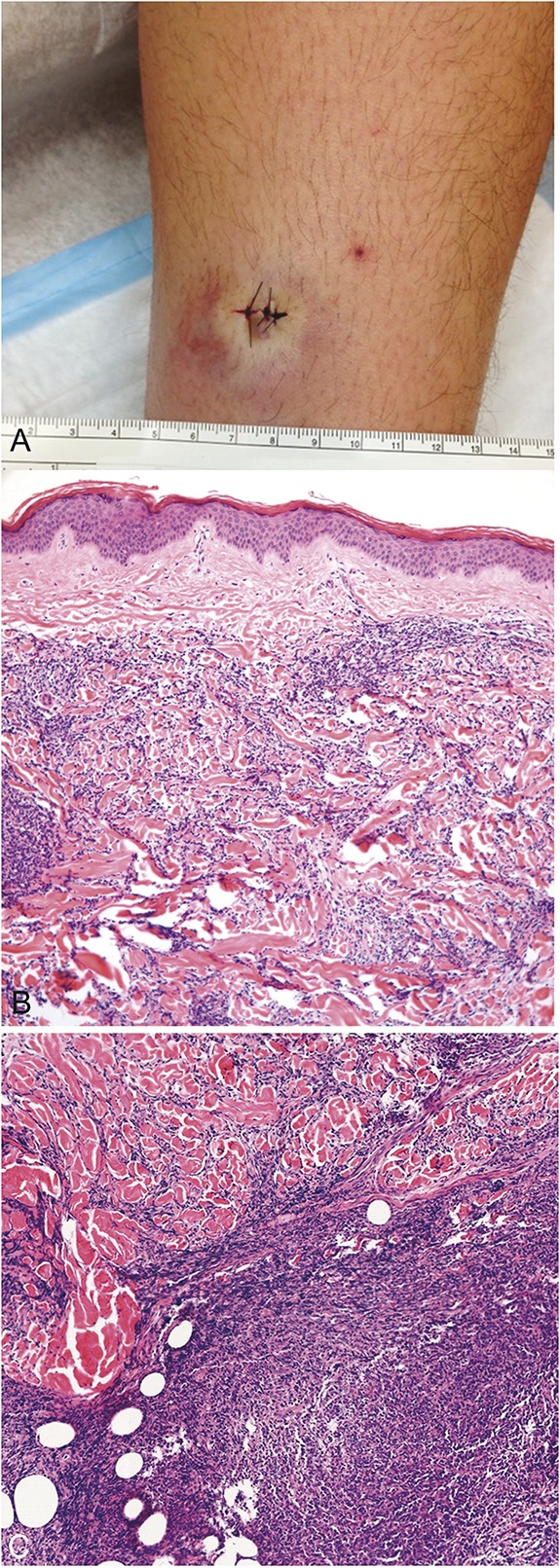

A 15-year-old boy presented with a 4-month history of an enlarging subcutaneous nodule on the lower leg (Fig. 3A). Although there was clinical suspicion for panniculitis, magnetic resonance imaging suggested a vascular lesion. Initial biopsy revealed a superficial and deep lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, interpreted as inflammatory in nature. Over the following 2 months, the nodule continued to grow. The patient experienced intermittent warmth and tingling in the lesion. Repeat deeper biopsy showed a diffuse monomorphic proliferation of atypical hematolymphoid cells infiltrating the reticular dermis and subcutis (Fig. 3B). The cells were medium sized with indented nuclei, scant cytoplasm, and finely dispersed chromatin (Fig. 3C). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for CD4, CD33, CD43, CD56, CD123, and TdT and negative for CD3, CD20, CD30, CD79a, CD117, myeloperoxidase, and PAX5, confirming the diagnosis of BPDCN.

FIGURE 3.

Examination and skin biopsy findings of Case 2. A, Single bruise-like subcutaneous nodule. Biopsy revealed a proliferation of atypical hematolymphoid cells infiltrating the reticular dermis and subcutis but sparing the papillary dermis (B). The infiltrate was arranged in a sheet-like and interstitial distribution (C).

Microscopic examination of cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood failed to detect neoplastic cells. However, minimal bone marrow involvement (<1%) was identified by flow cytometric analysis. The patient soon began treatment with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)–type chemotherapy. Subsequent bone marrow and skin biopsies have shown no residual disease. To date, the patient remains disease-free, 20 months after initial diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

BPDCN is an uncommon hematolymphoid neoplasm, often presenting as cutaneous lesions followed by rapid leukemic dissemination.2 The first reported case was published in 1994 by Adachi et al3 who described a CD4+ lymphoma with high CD56 (N-CAM) expression. Over the years, this neoplasm has been referred to by various names, including blastic natural killer cell (NK cell) lymphoma and CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm.4 Although originally thought to be a T-cell lymphoma because of its CD4 expression, the presence of CD56 suggested a blastic NK cell–derived lymphoma.4 However, more recent studies showed that the cells are negative for EBV and NK cell markers and positive for CD123 and TCL1, findings which are suggestive of plasmacytoid dendritic cells.4–6 As a result, BPDCN is now considered to be derived from plasmacytoid dendritic cell type II precursors.

BPDCN typically affects older males, with a median diagnostic age of 67 years.2,7 In the pediatric population, BPDCN is exceedingly rare, with only 33 published cases to date, and can present as young as 8 months old.1,8 The congenital form is even more rare, with only 1 case reported thus far.9 Approximately 85% of BPDCN cases show cutaneous involvement at presentation, although this number is slightly lower (76%) in the pediatric population.1 A wide spectrum of clinical presentations have been described, ranging from a single nodule to widespread cutaneous manifestations. Fass et al10 reported a case in which multiple cutaneous tumors were dispersed on the face, trunk, and extremities. In the largest case series to date by Julia et al,11 most patients (73%) presented with nodular lesions only, whereas other patients had bruise-like patches (12%) or mixed lesions including macules and nodules (14%). Involvement of extracutaneous organs is often seen and may account for the poor survival rate of patients. At the time of initial staging, it has been reported that two-thirds of patients display bone marrow, lymph node, and/or peripheral blood involvement.11 However, the frequency of metastases is controversial, as only one-third of patients were noted by Cota et al12 to be positive at initial staging.

Microscopically, BPDCN is characterized by a diffuse monomorphic infiltrate of medium-sized plasmacytoid cells with scant cytoplasm and fine chromatin.13 Classically, the cells express CD4, CD56, and plasmacytoid dendritic cell markers (CD123, BDCA-2/CD303, TCL1) in the absence of B-, T-, and myelomonocytic lineage-specific markers.13 However, as some markers may be negative, a defining immunophenotype must be broad to include all possible phenotypic variations.12

To establish a proper diagnosis, several authors have proposed a set of immunohistochemical staining criteria. Fanny et al have suggested that a “confident diagnosis” can be rendered when 4 of the 5 principle markers (CD4, CD56, CD123, BDCA-2/CD303, and TCL-1) are expressed.14 Other authors have suggested a scoring system based on the results by flow cytometry for cases with leukemic dissemination. Additionally, it has been recommended to include additional markers such as EBV to rule out an extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma and CD15 or lysozyme to exclude CD56+ acute leukemia cutis.2 Because of the variety of differential diagnoses with similar microscopic properties, an extensive immunohistochemical panel is key to arriving at the diagnosis of BPDCN.

Although therapeutic guidelines have yet to be established, most patients are treated with chemotherapy regimens used to treat acute leukemia or lymphoma. Although most patients achieve remission, up to 60% of patients relapse at an average of 5 months after chemotherapy alone.7,15 Recent studies suggest that allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (SCT) may play a vital role in achieving optimal treatment. In the largest study to date of SCT for BPDCN in the elderly population, Roos-Weil et al16 achieved a significantly improved rate of relapse of 32% at 3 years after SCT. SCT was studied after either myeloablative or reduced-intensity chemotherapy regimens. It was found that the combination of high-intensity myeloablative chemotherapy with SCT yielded better results.16 One case reported successful treatment with bone marrow transplantation after pretreatment with l-asparaginase, which decreased blasts before bone marrow transplantation.17 The median time from diagnosis to SCT was 6 months and was executed after the patient received an acute leukemia–type chemotherapy.16

Recently, alternative therapeutic avenues have also been explored. Frankel et al18 performed a prospective pilot study using the diphtheria toxin to cause apoptosis in malignant BPDCN cells. BPDCN cells have been shown to express IL3 receptors on their cell surface.19 These same receptors are absent on normal hematopoietic stem cells.20 By combining the catalytic and translocation domains of the diphtheria toxin with IL3, SL-401 was created to target these receptors.18 Once the IL3 domain of SL-401 is bound to its receptor found on the malignant BPDCN cells, SL-401 is internalized and causes apoptosis.18 A majority of patients treated with SL-401 (78%) showed clinical response, and it was suggested that SL-401 be used as induction therapy before SCT.18

Although the effectiveness of various treatment regimens has been well documented in the adult population, the response of the pediatric population to similar treatments remains unclear. Several therapeutic regimens have been used in the pediatric population, including ALL-type and acute myeloid leukemia–type chemotherapy and SCT.3,21 Recently, a pediatric case with metastasis to the lungs showed a dramatic response to non–Hodgkin lymphoma–Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster 95 (NHL-BFM95) therapy, which has been used in a limited number of cases.22 Several studies suggest that ALL chemotherapy achieves the best outcomes, with multiple patients achieving long-term clinical remission.23 The role of SCT remains questionable. In a study by Jegalian et al,1 the overall survival rate was 67% (4/6) in patients who underwent SCT and increased to 74% (14/19) in patients who did not receive any SCT therapy. However, in a review of 33 cases, the survival rates with SCT were higher than that without SCT, at 75% (6/8) versus 67% (16/24).24 In cases where no bone marrow donor is available, unrelated cord blood transplantation has also been shown to be a successful alternative to SCT.25

The prognosis of patients with BPDCN is usually poor, with most patients dying of disease within 12–14 months.8 However, pediatric cases of BPDCN seem to harbor a better prognosis. Other factors associated with a favorable prognosis include a lack of cutaneous involvement. It was noted that a survival rate of 100% (7/7) existed in cases without cutaneous involvement and 61% (11/18) in patients with cutaneous symptoms.1 This could be attributed to the less aggressive nature of the disease when the skin is spared.

Within these existing studies lie possible faults in analysis. An assessment of the average time of follow-up when survival was recorded showed a longer mean follow-up time for survived cases than deceased cases. Furthermore, the standard deviation of follow-up time for both survived and deceased cases is high, at times exceeding the mean value. This suggests that regular follow-up intervals of patients should be implemented in future studies to reduce the variation in values for a more consistent and statistically accurate analysis.

In summary, BPDCN is a rare aggressive hematolymphoid neoplasm, which usually affects older males. Cases in the pediatric population are exceptionally rare but may be associated with a more favorable outcome. Because of the limited number of pediatric cases reported, a standard treatment regimen has yet to be established. The successful clinical remission seen in one of our patients contributes to defining the role of SCT in the treatment of BPDCN. Additional cases must be defined, and larger studies of pediatric cases should be preformed to establish optimal treatment.

Footnotes

L. Stuart and H. Skupsky had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drafting of the manuscript: C. M. Nguyen, H. Skupsky, and L. Stuart. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and study supervision: A. Tsuchiya and D. S. Cassarino.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jegalian AG, Buxbaum NP, Facchetti F, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm in children: diagnostic features and clinical implications. Haematologica. 2010;95:1873–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magro CM, Porcu P, Schaefer J, et al. Cutaneous CD4+ CD56+ hematologic malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:292–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi M, Maeda K, Takekawa M, et al. High expression of CD56 (N-CAM) in a patient with cutaneous CD4-positive lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 1994;47:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herling M, Jones D. The features of an evolving entity and its relationship to dendritic cells. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:687–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichard KK, Burks EJ, Foucar KM, et al. CD4(+) CD56(+) lineage-negative malignancies are rare tumors of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1274–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urosevic M, Conrad C, Kamarashev J, et al. CD4+ CD56+ hematodermic neoplasms bear a plasmacytoid dendritic cell phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1020–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reimer P, Rüdiger T, Kraemer D, et al. What is CD4+ CD56+ malignancy and how should it be treated? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu SCS, Tsai KB, Chen GS, et al. Infantile CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm. Haematologica. 2007;92: 91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tokuda K, Eguchi-Ishimae M, Yagi C, et al. CLTC-ALK fusion as a primary event in congenital blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;53:78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fass J, Tichy EH, Kraus EW, et al. Cutaneous tumors as the initial presentation of non-T, non-B, nonmyeloid CD4+ CD56+ hematolymphoid malignancy in an adolescent boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot‐Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cota C, Vale E, Viana I, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm—morphologic and phenotypic variability in a series of 33 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facchetti F, Ungari M, Marocolo D, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Hematol Meeting Rep. 2009;3:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angelot-Delettre F, Biichle S, Ferrand C, et al. Intracytoplasmic detection of TCL1—but not ILT7—by flow cytometry is useful for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell leukemia diagnosis. Cytometry A. 2012;81A:718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalle S, Beylot-Barry M, Bagot M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: is transplantation the treatment of choice? Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roos-Weil D, Dietrich S, Boumendil A, et al. Stem cell transplantation can provide durable disease control in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a retrospective study from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2013;121:440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyakuna N, Toguchi S, Higa T, et al. Childhood blastic NK cell leukemia successfully treated with L-asparagenase and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42:631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frankel AE, Woo JH, Ahn C, et al. Activity of SL-401, a targeted therapy directed to interleukin-3 receptor, in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients. Blood. 2014;124:385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garnache-Ottou F, Feuillard J, Ferrand C, et al. Extended diagnostic criteria for plasmacytoid dendritic cell leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:624–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan CT, Upchurch D, Szilvassy SJ, et al. The interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain is a unique marker for human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Leukemia. 2000;14:1777–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambichler T, Pantelaki I, Stücker M. Childhood blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm treated with allogenic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:142–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong XD, Wnag LZ, Wang X, et al. Diffuse lung metastases in a child with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm and review. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:1667–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruggiero A, Maurizi P, Larocca LM, et al. Childhood CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm: case report and review of the literature. Haematologica. 2006;91:ECR48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakashita K, Saito S, Yanagisawa R, et al. Usefulness of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission for pediatric blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with skin involvement: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:E140–E142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshimasu T, Manabe A, Tanaka R, et al. Successful treatment of relapsed blastic natural killer cell lymphoma with unrelated cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30:41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]