1. INTRODUCTION

With drug discovery from marine natural products hailing a renaissance over the past 5 years, the use of marine extracts in the search for biologically active natural products continues to be a powerful approach for the identification of lead compounds for chemistry programs involved in drug discovery.1 Natural products continue to serve as valuable starting points in developing druglike candidates, and the first step in the development of therapeutic agents is the identification of lead compounds that bind to a specific target or receptor of interest.2 Structure-activity relationships (SARs) of lead compounds are then studied by synthesis or semisynthesis of a number of analogues to define the key recognition elements for maximal activity.3

However, the role of natural products in drug discovery became a lower priority in terms of participation by the major pharmaceutical companies by the mid-1990s.4 Reasons for this decline include the perceived disadvantages of natural products, including difficulties in access and supply, structure elucidation and synthesis because of the complexity of natural products, and concerns about intellectual property rights associated with published structures and international collections. In addition, the availability of large collections of compounds prepared by combinatorial chemistry methods provides inexpensive access to large numbers of molecules for random screening and starting materials for rational design.5,6

Nevertheless, the natural products chemistry field has welcomed a renaissance over the past 5 years because of new developments in analytical chemistry, spectroscopy highthroughput screening, and a disappointing number of leads generated through combinatorial chemistry.1,7-9 Currently, basic scientific research in chemistry and biology of marine natural products that started in the 1970s has finally borne fruit for marine-derived drug discovery. Ziconotide (Prialt; Elan Pharmaceuticals), a peptide originally discovered from a tropical cone snail, was the first marine-derived compound approved in the United States in December 2004 for the treatment of pain. Then, in October 2007, trabectedin (Yondelis; PharmaMar) was approved and became the first marine anticancer drug in the European Union. Collaborations between industrial and academic scientists continue to meet the challenges involved in discovering, understanding, and developing new anticancer drugs.10 Several other candidate compounds from marine origins are in the pipeline and are being evaluated in phase I-III clinical trials for the treatment of various cancers in the United States and in Europe.11-13 Here, we review the kahalalides, a family of structurally unrelated depsipeptides isolated from the herbivorous marine mollusk Elysia rufescens, Elysia ornata, or Elysia grandifolia and their algal diet of Bryopsis pennata.14-27 Two of the most active compounds of this family, kahalalide F (KF) (6) and isoKF (22), have been evaluated in phase II clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and melanoma. Moreover, KF (6) is being evaluated in phase II clinical trials in patients with severe psoriasis.83-93 Of greatest significance is the fact that KF (6) can effectively inhibit receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB3 (HER3) and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt signaling pathways in sensitive cell lines, which suggests that KF (6) and isoKF (22) are involved in an unknown oncosis signaling pathway, though the mechanism of action has not yet been completely characterized.103-107 The kahalalides would represent the first anticancer drugs that can inhibit HER3 receptors.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Discovery and Isolation of Naturally Occurring Kahalalides

The kahalalides (Figure 1) consist of a series of depsispeptides that were first identified from the herbivorous marine mollusk E. rufescens, E. ornata, or E. grandifolia and later from their algal diet of B. pennata or Bryopsis plumosa (Figure 2).16 The size and composition of this series of peptides are highly variable, ranging from a C31 tripeptide to a C77 tridecapeptide, and each peptide contains a different relatively obscure fatty acid (Table 1). Many review articles and patents on the kahalalides have appeared in the literature.28-60 The initial discovery of KF (6) and its closely related isomer, isoKF (22), was first reported by Hamann and Scheuer in 1993.14,15 In the course of the investigation of natural products from the mollusk E. rufescens and the alga B. pennata, the constituents were shown to be dominated by amino and fatty acid-derived depsipeptides. Isolation of seven compounds, kahalalides A-E, F/isoKF, and G, was accomplished using silica gel and preparative HPLC. The largest and most active peptide, KF (6), and its closely related isomer, isoKF (22), exhibited significant activity in vitro against various solid tumor cell lines.

Figure 1.

Structures of kahalalide peptides.

Figure 2.

Photograph of the sacoglossan mollusk E. rufescens and the green alga B. pennata collected from Hawaii (photo by M. Huggett).

Table 1.

Comparative Composition of Kahalalides

| amino aicds |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kahalalide | mol formula | mol wt | Ala | Arg | Asp | Asn | Dhb | Glu | Gly | Ile | Leu | Lys | Orn | Phe | Pro | Hyp | Ser | Thr | Trp | Tyr | Val | fatty acid | refs | |

| 1 | A | C46H67N7O11 | 894.5 | D(2) | D(2) | L(1) | L(2) | 2-Me-Bu | 15 | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | B | C45H63N7O11 | 878.5 | 1 | D(1) | L(1) | L(1) | L(1) | L(1) | L(1) | 5-Me-Hex | 15 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | C | C47H63N9O10 | 914.5 | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | L(1) | D(2) | Bu | 15 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | D | C31H45N7O5 | 595.4 | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | 7-Me-3-Octol | 15 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | E | C45H69N7O8 | 836.5 | D(2) | 2 | L(1) | L(1) | 9-Me-3-Decol | 15 | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | F | C75H124N14O16 | 1477.9 | Z(1) | Da(2)a | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | L(1) Da(1) |

D(3) L(2) | 5-Me-Hex | 14, 24-27 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | G | C75H126N14O17 | 1495.9 | Z(1) | Da(2) | L(1) | D(1) | L(1) Da(1) |

D(3) L(2) |

5-Me-Hex | 15 | |||||||||||||

| 8 | H | C55H82N8O16 | 1110.5 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) L(1) |

L(1) | L(2) | D(1) | 9-Me-3-Decol | 16 | |||||||||||||

| 9 | J | C61H94N10O17 | 1239.7 | D(1) | D(1) | L(1) | 2 | L(1) | L(2) | D(1) | 9-Me-3-Decol | 16 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | K | C46H66N7O11 | 892.5 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | L(1) | L(1) | L(1) | 9-Me-3-Decol | 17 | |||||||||||||

| 11 | 0 | C48H68N8O11 | 933.5 | 1 | L(1) | 2 | D(1) | D(1) | L(1) | 5-Me-Hex | 18 | |||||||||||||

| 12 | P | C66H99N11O17 | 1318.7 | D(1) | L(1) | D(1) L(1) |

L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | 9-Me-3-Decol | 19 | |||||||||||||

| 13 | Q | C66H100N11O16 | 1302.7 | D(1) | D(1) | L(1) | D(1) L(1) |

L(2) | D(1) | 9-Me-3-Decol | 19 | |||||||||||||

| 14 | R1 | C77H127N14O17 | 1519.9 | Z(1) | D(1) | Da(1) | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | Da(1) | 6 | 7-Me-Oct | 20 | |||||||||||

| 15 | S1 | C77H127N14O18 | 1535.9 | Z(1) | D(1) | Da(1) | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | Da(1) | 6 | 7-Me-5-Octol | 20 | |||||||||||

| 16 | R2 | C74H121N14O16 | 1464.0 | (1) | (1) | (1) | (1) | (1) | (2) | 6 | 5-Me-Hex | 21 | ||||||||||||

| 17 | S2 | C76H126N14O16 | 1492.0 | (1) | (1) | 1 | (1) | (1) | (1) | (2) | 5 | 5-Me-Hex | 21 | |||||||||||

| 18 | V | C31H47N7O6 | 614.3 | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | 7-Me-3-Octol | 22 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19 | w | C31H45N7O6 | 612.3 | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | 7-Me-3-Octol | 22 | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | X | C47H66N9O11 | 932.5 | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | L(1) | D(2) | Bu | 22 | ||||||||||||||

| 21 | Y | C46H66N7O10 | 876.5 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | L(1) | L(1) | L(1) | 9-Me-3-Decol | 22 | |||||||||||||

| 22 | isoKF | C75H124N14O16 | 1477.9 | Z(1) | Da(2) | L(1) | D(1) | L(1) Da(1) |

D(3) L(2) |

4(S)-Me-Hex | 14, 35 | |||||||||||||

| 23 | NorKA | C45H65N7O11 | 880.5 | D(2) | D(2) | L(1) | L(2) | IsoBu | 23 | |||||||||||||||

| 24 | 5-OHKF | C75H124N14O17 | 1493.9 | Z(1) | Da(2)a | L(1) | L(1) | D(1) | L(1) Da(1) |

D(3) L(2) | 5-OH-5-MeHex | 23 | ||||||||||||

D-allo configuration of amino acids.

The sea slug E. rufescens and the alga B. pennata were extracted with ethanol and subjected to silica gel flash chromatography with a stepwise gradient: n-hexane, n-hexane/EtOAc (1:1), EtOAc, EtOAc/MeOH (1:1), MeOH, and MeOH/H2O (50:50). The EtOAc/MeOH (1:1) fraction was found to contain the depsipeptides. HPLC using an RP C18 column and a gradient from a H2O/MeCN/TFA mixture (70:30:0.1) to a H2O/MeCN/TFA mixture (45:55:0.1) yielded the kahalalides, and final purification was completed using isocratic conditions.14,15,30-32

IsoKF (22) is the (4S)-methylhexanoic isomer of KF and remains inseparable from KF (6) under preparative scale conditions but can be resolved using LC-TOF-MS (6).14 This compound is currently obtained via a synthetic process by PharmaMar.35 The activity of isoKF (22) was similar to that of KF (6) and showed enhanced efficacy against breast and prostate tumor cell lines. Currently, the compound has entered phase I clinical trials in advanced pretreated solid tumors.

Because KF (6) and isoKF (22) exhibit significant bioactivity against various solid tumor cell lines, isolation of new kahalalide peptides became of interest for natural products chemists. Since 1997, the structures of 16 new kahalalide derivatives have been elucidated and 14 of them isolated.16-23 In 1997, Scheuer et al. reported two acyclic kahalalide peptides, kahalalides H (8) and J (9) from the mollusk E. rufescens.16 Kahalalides H (8) and J (9) share only four amino acids (leucine, phenylalanine, serine, and valine). They have in common a 3-hydroxy-9-methyldecanoic acid, previously encountered in kahalalide E (5). In common with the acyclic constituent of the alga-derived kahalalide G (7), kahalalides H (8) and J (9) exhibited no significant activity. In 1999, a new peptide kahalalide K (10) was isolated from the alga B. pennata and kahalalide K (10) was determined to possess a new array of L-amino acids (Val, Tyr, and Hyp), D-amino acids (Asn, Phe, and Ala), and a 3-hydroxy-9-methyldecanoic acid previously reported in kahalalides E (5), H (8), and J (9).17 In 2000, one new cyclic peptide, kahalalide O (11), was identified from the sacoglossan E. ornata and the alga B. pennata followed by the isolation of kahalalides P (12) and Q (13), which also possessed (3R)-hydroxy-9-methyldecanoic acid determined by Mosher’s ester procedure.18,19 In 2006, new KF analogues, kahalalides R1 (14) and S1 (15), were isolated from E. grandifolia, and kahalalide R1 (14) was found to exert comparable or even higher cytotoxicity than KF (6) toward the MCF7 human mammary carcinoma cell line.20 Kahalalides R1 (14) and S1 (15) differed in only the fatty acid. The fatty acid residues in kahalalides R1 (14) and S1 (15) were 7-methyloctanoic acid (7-Me-Oct) and 5-hydroxy-7-methyloctanoic acid (7-Me-5-Octol), respectively. Kahalalides R1 (14) and S1 (15) were shown to contain six units of valines and one unit each of Phe, Ile, Thr, Orn, Pro, Glu, and dehydroaminobutyric acid. In kahalalides R1 (14) and S1 (15), Val and Glu units replaced Thr and Ile units previously found in KF (6). The absolute configuration of amino acids was determined by Marfey’s analysis,61 which identified one unit of D-Glu, D-Pro, L-Orn, D-allo-Ile, D-allo-Thr, and L-Pro. Absolute configuration of the individual Val units could not be unambiguously determined because Marfey’s analysis suggested the presence of D- and L-isomers in these two compounds, and there are three units of Val in both the cyclic and linear fragments. In 2007, two new KF analogues, kahalalides R2 (16) and S2 (17) (their names are identical to the two compounds isolated by Ashour et al. in 2006), were characterized by using tandem mass spectrometry.21 The amino acid sequences of kahalalides R2 (16) and S2 (17) were proposed by collision-induced dissociation (CID) experiments with singly and doubly charged molecular ions and by comparison with the amino acid sequences of KF (6). The absolute configuration of kahalalides R2 (16) and S2 (17) could not be assessed by chemical methods because no pure kahalalide R2 (16) or S2 (17) was isolated from the mollusk E. grandifolia. In 2008, four new kahalalide peptides from the mollusk E. rufescens were reported.22 Kahalalide V (18) was identified as an acyclic derivative of kahalalide D (4), while kahalalide W (19) was determined to have a 4-hydroxy-L-Pro residue instead of the proline in kahalalide D (4). Kahalalide X (20) was an acyclic derivative of kahalalide C (3), and kahalalide Y (21) was found to have an L-proline residue instead of the hydroxyproline in kahalalide K (10). In 2009, our group isolated two new kahalalide peptides, NorKA (23) and 5-OHKF (24). NorKA (23) and KA (1) differ in only a methylene group.23 The former contains an isobutyric acid as the fatty acid moiety and the latter a 2-methylbutyric acid. 5-OHKF (24) and KF (6) are different in one hydroxyl group. The fatty acid residue of 24 is 5-hydroxy-5-methylhexanoic acid.

2.2. Structure Elucidation of Kahalalides

The gross structure proposed for the kahalalide peptides was deduced from NMR methods and mass spectrometry.14-23 Tandem mass spectrometry is also a useful tool that can provide detailed information for characterizing the kahalalide peptides.21 In most cases, the absolute configuration of each amino acid in the peptide can be determined by Marfey’s methods after hydrolysis.54 L-FDAA (1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyL-5-L-alanine amide), Marfey’s reagent, reacts by nucleophilic substitution of the aromatic fluorine with the free amino group on an amino acid. When a racemic mixture of amino acids is treated with this reagent, the production of analogous diastereomers occurs. These diastereomers can be separated using reverse phase HPLC. However, it is not possible to determine the sequential position of the DL-antipodal amino acids by Marfey’s method.14,16,18,20,23

The structure of KF (6) and isoKF (22) was initially reported to contain a cyclized macrolide region consisting of two Val residues, one D-allo-Ile, one Thr, one dehydroaminobutyric acid, and one L-Phe, a linear region including three Val residues, one D-allo-Ile, one L-Orn, one Thr, one D-Pro, and a methylhexanoic acid, conjugated with the N-terminus.14 In the ring, the carboxyl group of the Val was linked to Thr through the hydroxyl group. The proposed structure of KF (6) was based upon NMR methods, degradation by acid hydrolysis, mass spectrometry, and GC analysis of the individual amino acid components using Marfey’s reagent. Only the Ile, Orn, Pro, and Phe amino acids have one stereoisomer. However, further work was needed to investigate the absolute configuration of the conundrum posed by multiple possible stereoisomers in the molecule including three D-Val and two L-Val isomers together with one D-allo-Thr isomer and one L-Thr isomer. The remaining absolute configuration was reported by Goetz and Scheuer,24,25 and Val-3 and Val-4 were assigned the L- and D-configurations, respectively. The group of Albericio and Giralt at the University of Barcelona27 synthesized the originally proposed structure and showed the differences in chromatographic and spectroscopic behavior between the synthesized peptide and the natural peptide. Later, Rinehart et al. at the University of Illinois elected to reinvestigate the absolute configuration of KF (6) and finally suggested that the absolute configuration of Val-3 and Val-4 should be reversed and played an important role in the activity of KF (6) and isoKF (22) because the depsipeptide with L-Val-3 and D-Val-4 in its structure was not active, while the molecule with D-Val-3 and L-Val-4 was active.26 In 2006, the group of Dmitrenok and Nagai used a carboxypeptidase hydrolysis reaction to determine the sequential positions of the DL-Phe in kahalalides P (12) and Q (13).19 The absolute configuration of amino acids in 5-OHKF (24) was achieved by the combination of chemical hydrolysis and Marfey’s method.23 Amino acid analysis by Marfey’s method revealed 12 amino acids: L-Orn, D-allo-Ile (two), D-Pro, L-Thr, D-allo-Thr, D-Val (three), L-Val (two), and L-Phe. A single Marfey’s analysis was not enough because there is more than one valine or threonine that has a different absolute configuration. We hydrolyzed 5-OHKF (24) and KF (6) partially into smaller units without the fatty acid residues and then assessed their chromatographic properties. So far, the sequential positions of DL-antipodal Leu in kahalalide E (5), DL-antipodal Phe in kahalalide J (9), L-Thr and D-allo-Thr in kahalalide O (11), and DL-antipodal valine in kahalalides R1 (14) and S1 (15) remain unassigned.16,18,20

2.3. Biological Activity Profiles

2.3.1. Cytotoxicity and Antitumor Activity

Among the kahalalides, only kahalalides A (1), E (5), F (6)/isoKF (22), R1 (14), isoKA (23), and 5-OHKF (24) exhibited significant biological activity (Table 2). In 2001, Becerro et al. studied the ecological role of KF (6).62 The results showed that KF (6) protected both B. pennata and E. rufescens from fish predation. E. rufescens is a chemically defended species. In fact, it is possible that E. rufescens has evolved defensive mechanisms to reduce its chances of predation. B. pennata is a chemically defended alga that may provide the sacoglossan an associational refuge. By feeding on B. pennata, E. refescens sequesters algal chloroplasts and makes itself highly cryptic.63-67 However, the risk of predation may still be high for cryptic organisms, so the acquisition of other defensive strategies may expand the benefits of crypsis. E. rufescens sequesters the antipredatory compound KF (6) from B. pennata, accumulating it a concentration several times the concentration in the alga, and uses KF (6) to chemically defend itself. Moreover, E. rufescens generates KF (6) the mucus. Therefore, KF (6) is responsible for the deterrent properties of the mollusk. It is hypothesized that the KF-producing Vibro sp. from the surface of B. pennata are acquired by E. rufescens, which maintains the bacteria as symbionts.39,43

Table 2.

Biological Activity Profile of Kahalalides

| kahalalide | biological activity | refs |

|---|---|---|

| A (1) | in vitro activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 83% inhibition at 12.5 g/mL | 15 |

| E (5) | selective activity against herpes simplex II virus (HSV II) | 15 |

| F (6) | selectivity against solid tumor cell lines: IC50 values of 2.5, 0.25, and <1.0 μg/mL against A-549, HT-29, and LOVO, respectively; IC50 values of 10 and >10 μg/mL against P-388 and KB, respectively; KF is active against CV-1 cells with an IC50 of 0.25 μg/mL |

14, 15, 68–70 |

| antiviral activity: 0.5 μg/mL (95% reduction) with HSV II using mink lung cells | ||

| antifungal activity: IC50 values of 3.02 μM against Candida albicans, 1.53 μM against Candida neoformans,

and 3.21 μM against Aspergillus fumigatus |

||

| immunosuppressive activity: IC50 of 3 μg/mL in a mixed lymphocyte reaction assay, IC50 of 23 μg/mL with lymphocyte viability (LcV) |

||

| antileishmanial activity: LC50 values of 6.13 μM against Leishmania donovani (promastigote), 8.31 μM against Leishmania pifanoi (promastigote), 29.53 μM against L. pifanoi (amastigotes); in vitro antitumor activity similar to that of KF (6) |

||

| IsoKF (22) | IsoKF (22) has enhanced efficacy against breast and prostate xenografts | 35, 70 |

| R1 (14) | IC50 of 0.14 mmol/L against the human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cell line | |

| IC50 of 4.28 mmol/L against the mouse lymphoma L1578Y cell line | 20 | |

| NorKA (23) | 100 μM norKA (2) inhibited 82% of the specific binding of [3H]NPY to the Y1 receptor, and it showed no inhibitory activity (only 4%) for [3H]BQ-123 binding to the ETA receptor |

23 |

| 5-OHKF (24) | in vitro antimalarial activity against D6 and W2 clones of Plasmodium falciparum with IC50 values of 1.5 and 1.2 μg/mL, respectively |

23 |

Early preclinical data showed that KF (6) exhibited a potent new chemical entity with significant cytotoxicity against solid tumor cell lines.110 Preliminary in vitro screening studies indicated micromolar activity of KF (6) against selected cell lines, in particular NSCL, colon, ovarian, and breast cancers and especially prostate cancer (Table 2). In vitro cell culture studies indicated that 10 μM KF (6) could produce cytotoxicity to central nervous system neurons but not astrocytesa or sensory and motor neurons.80

A human tumor colony-forming unit (TCFU) assay from surgically derived tumors showed that KF (6) completely inhibits breast, colon, kidney, NSCLC, ovary, prostate, stomach, and uterine tumor specimens. An IC50 of <10 nM in a limited number of specimens has been identified, and prostate and stomach tumor specimens are the most sensitive.71

In vitro antitumor activity of isoKF (22) is similar to that of KF (6). However, isoKF (22) has enhanced efficacy against breast and prostate xenografts.35,70

Kahalalides R1 (14) and KF (6) were tested and found to be comparably cytotoxic toward MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values of 0.14 and 0.22 μM, respectively. Furthermore, kahalalide R1 was cytotoxic toward the mouse lymphoma L1578 Y cell line with an IC50 of 4.26 nM, almost identical to that of KF (6).20

2.3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

In 1996, Hamann et al. reported that KA (1) was shown to inhibit 83% of the growth of M. tuberculosis at 12.5 μg/mL. KF (6) exhibited antifungal activity with IC50 values of 3.02 μM against C. albicans, 1.53 μM against C. neoformans, and 3.21 μM against A. fumigates.69 In an agar diffusion assay, KF (6) exhibited strong antifungal activity at a level of 5 μg/disk against the plant pathogens Cladosporium herbarum and Cladosporium cucumerinum with inhibition zones of 17 and 24 mm, respectively.20 Kahalalide R1 (14) also exhibited significant antifungal activity against the two species with inhibition zones of 16 and 24 mm, respectively.20

KF (6) exhibited antiviral activity at 0.5 μg/mL (95% reduction) with herpes simplex II virus (HSV II) using mink lung cells. Furthermore, KF (6) exhibited selective activity against some of the AIDS opportunistic infections.14,15

KE (5) also exhibited selective activity against herpes simplex II virus (HSV II).15

2.3.3. Antileishmanial Activity

KF (6) was tested for its activity against promastigote and amastigote stages of Leishmania. Their respective LC50 (concentration at which the proliferation of the parasites was inhibited by 50%) values are listed in Table 2.

2.3.4. Immunosuppressive Activity. KF (6) exhibited slight immunosuppressive activity in a mixed lymphocyte reaction assay (MLR) with an IC50 of 3 μg/mL, and with a lymphocyte viability (LcV) IC50 of 23 μg/mL.14

3. METABOLISM AND PHARMACOKINETICS OF KF

3.1. Metabolism of KF

An analytical method using HPLC with positive ion turbo-ion spray tandem MS has been applied to the study of KF (6) in human plasma. Ammonium acetate was chosen to replace trifluoroacetic acid to enhance sensitivity in the positive ion mode.72-74 A lower-limit quantitation of 1 ng/mL using a 500 μL sample volume and a linear dynamic range extending to 1000 ng/mL were obtained, and KF (6) was stable in the biomatrix for a period of 9 months at −20 °C and 24 h at room temperature. The interassay accuracy was −15.1% at the lower limit of quantitation and between −2.68 and −9.05% for quality control solutions ranging in concentration from 2.24 to 715 ng/ mL.72 The analyte was stable in plasma for 16 h after reconstitution of plasma extracts for liquid chromatography analysis at room temperature.

High-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection was used to study the chemical degradation of KF (6) under acid, neutral, and alkaline conditions, and the results showed that the half-lives (t1/2) of KF (6) at 80 °C were 1.1, 20, and 8.6 h at pH 0, 1, and 7, respectively.75 The half-life of KF (6) at 26 °C and pH 11 was 1.65 h. Kahalalide G (7), the only product of KF (6), was produced at pH 7 and 11. In addition, metabolic conversion of KF (6) was conducted using three different enzyme systems, including pooled human microsomes, pooled human plasma, and uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronyl transferase. Biotransformation was not observed during these in vitro studies, so KF (6) was metabolically stable.

Furthermore, infrared (IR) spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were applied to investigate stabilities of 6-lyophilized products containing crystalline (mannitol) or amorphous (sucrose) bulking agents at 5 and 30 °C with or without 60% relative humidity (RH) in the dark. A stable lyophilized formulation was created, and it contained 100 μg of KF (6), 100 mg of sucrose, 2 mg of polysorbate 80, and 2.1 mg of citric acid monohydrate to be reconstituted with a vehicle composed of 5%/5%/90% (v/v/v) CEW and to be diluted further using normal saline.76 Lyophilized products became less stable when polysorbate 80 and citric acid monohydrate concentrations were increased. Sorption to contact surfaces with an infusion container composed of low-density polyethylene could lead to loss of KF (6).77,78 Therefore, KF (6) must be administered in a 3 h infusion at concentrations of 0.5-14.7 μg/mL, and an administration set consisting of a glass container and a low-extrables, DEHP-free extension set must be used. An in vitro biocompatibility study was performed, and the results showed that no significant hemolysis due to the KF (6) formulation as well as the CE vehicle was found using a static or dynamic test model.79

IsoKF (22) was very stable in dog plasma, and no significant changes in concentration were observed after incubation for up to 4 h in a water bath at 37 °C.94

3.2. Pharmacokinetics of KF

An HPLC-MS assay method was utilized to determine the pharmacokinetics of KF (6) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic Profile of KF

| model used | results | refs |

|---|---|---|

| KF studied first in female mice for both intravenous and intraperitoneal administration of the drug (280 g/kg) |

Upon intravenous administration to mice, there was no accumulation of the drug after repeated intravenous administration at 24 h intervals and plasma levels declined from a peak concentration of 1.0 μM with a t1/2 of 35 min When the drug was administered intraperitoneally at the same dose, the peak concentration was 0.3 μM approximately 1 h after dosing. |

81, 82 |

| phase I study in patients with androgen-refractory prostate cancer in which KF (20–930 mg/m2) was administered as a daily 1 h intravenous infusion for 5 days every 3 weeks |

A linear relationship between dose and AUC over a dose range of 20–560 g/m2/day. At doses of >560 g/m2/day, the AUC increased in a non-dose-proportional manner. On day 1, the total plasma clearance was 11.02 ( 4.54 L/h and the terminal t1/2 value of intravenous KF in these patients was 0.54 ± 0.14 h. |

83, 84, 111 |

| phase I study in patients with various solid tumors in which KF was administered as a continuous weekly 1 h intravenous infusion at doses ranging from 266 to 1200 g/m2 |

A linear relationship between dose and AUC over a dose range of 266–800 mg/m2/week. |

85 |

| phase I study in patients with advanced solid tumors in which KF was administered weekly as a 1 h intravenous infusion at a starting dose of 266 g/m2/day |

This schedule was characterized by linear kinetics for Cmax and AUC values, a short terminal half-time (0.52 h vs 0.47 h), and a narrow volume of distribution (5.5 L at the recommended dose with the once-weekly schedule vs 7.16 L at the recommended dose with the daily schedule). The volume of distribution and clearance increased with body size and were best predicted with body surface area and height, respectively. |

86, 109 |

| phase II study in patients with advanced malignant melanoma (AMM) in which KF was administered as a weekly 1 h intravenous infusion with a dose of 650 g/m2 |

Means (SD) of half-life, clearance, and volume of distribution at steady state were 0.49 h (0.15), 5.60 L h−1 m−2 (1.26), and 4.00 L/m2 (1.00), respectively. The pharmacokinetic profile of KF in phase II studies did not differ significantly from those found in phase I studies. |

87, 88 |

4. CLINICAL STATUS

Relevant preclinical experiments have shown that fractionation of a lethal or MTD dose of KF (6) by daily administration for 5 days reduces drug-induced toxicity and appears to be a viable option for the clinical evaluation of KF (6) for the treatment of cancer.113,114 The activity of KF (6) has been investigated in phase I clinical trials for androgen-refractory prostate cancer solid tumors and phase II clinical studies with patients having liver, non-small-lung cancer, melanoma, and psoriasis.83-92 Some results about clinical trials of KF (6) are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Clinical Trials of KF

| effect | model | results | refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| efficacy | phase I study in patients with androgen-refractory prostate cancer in which KF (20–930 mg/m2) was administered as a daily 1 h intravenous infusion for 5 days every 3 weeks |

Thirty-three patients were treated; one patient showed a significant decrease in PSA level (>50%) associated with clinical improvement (pain relief), while three patients exhibited stable disease for 2 (n = 2) or 7 (n = 1) months. The MTD was 560 mg/m2/day. |

84 |

| efficacy | phase I study in patients with various solid tumors in which KF was administered as a continuous weekly 1 h intravenous infusion at doses ranging from 266 to 1200 g/m2 |

Twenty-five patients were treated, and three patients achieved a clinical benefit: one hepatocarcinoma patient who received 24 infusions consisting of 400 g/m2/week, one squamous carcinoma cavum patient who received nine infusions at the same dose, and one NSCLC patient who received 16 infusions at a dose of 530 g/m2/week. The MTD was 1200 g/m2/week. |

85 |

| safety | two phase I trials in which 60 cancer patients were administered KF as a 1 h intravenous infusion |

Grade 4 AI was consistently the DLT and tended to coincide with LDH elevation and an ALT:AP ratio of >5.0, indicating hepatocellular damage; these effects were reversible and dose-dependent. |

89 |

| safety and efficacy |

phase I study in patients with advanced solid tumors in which KF was administered weekly as a 1 h intravenous infusion at a starting dose of 266 g/m2/day |

Thirty-eight patients were enrolled and received once-weekly KF 1 h infusions at doses between 266 and 1200 g/m2. Dose-limiting toxicities included transient grade 3/4 increases in transaminase blood levels. The maximal tolerated dose for the KF schedule was 800 g/m2, and the recommended dose for phase II studies was 650 g/m2. No accumulated toxicity was found. This schedule provided a favorable safety profile and hints of antitumor activity. |

86 |

| efficacy and safety |

phase I study in patients with androgen or metastatic-refractory prostate cancer in which KF was administered as a 1 h intravenous infusion for 5 consecutive days every 3 weeks with a starting dose of 20 g/m2/day |

Thirty-two patients were treated at nine dose levels (20–930 g/m2/day). The maximal tolerated dose on this schedule was 930 g/m2/day. The recommended dose for phase II studies is 560 g/m2/day. |

83 |

| efficacy and safety |

phase II study in patients with advanced malignant melanoma (AMM) in which KF was administered weekly as a 1 h intravenous infusion with a dose of 650 g/m2 |

Twenty-four patients were recruited. No objective responses were observed, but the duration of stable disease suggested some degree of antitumor activity. |

87 |

| response, safety, and tolerability |

phase II study in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in which KF was administered weekly as a 1 h intravenous infusion with a dose of 650 g/m2 |

Thirty-one patients were enrolled in this phase II trial. The primary results for efficacy showed no complete responses. One patient had a partial response; stability occurred in eight patients and disease progression in 11 patients. Six patients had stable disease lasting for more than 3 months. The duration of stable disease suggested some antitumor activity of KF in this indication, while its toxicity was clinically negligible. |

90 |

| efficacy, safety, and tolerability |

phase II study in patients with hepatocarcinoma (HC) in which KF was administered as a 1 h intravenous infusion with a dose of 650 g/m2 over 1 h per week until the disease failed to progress or unacceptable toxicity |

Twenty-two patients were recruited. No objective response was observed. Stable disease occurred in nine patients with a median duration of 4.8 months. Median progression free survival was 2.4 months. KF was well tolerated in this patient population, and stable disease was the best response observed in previously untreated patients with hepatocarcinoma (HC). |

91 |

IsoKF (22) has been selected for clinical development on the basis of its in vivo activity in xenografted human tumors, as well as an acceptable nonclinical toxicology profile. The compound is in phase I clinical trials in patients with advanced malignant solid tumors.92-94

5. TOTAL SYNTHESIS

As a result of the biological activity profile of the kahalalides, they, especially KF (6), have become synthetic targets in several laboratories. Some papers about total syntheses of some kahalalides have been published.27,95-98

5.1. Total Synthesis of KB

Kahalalide B (2) is the first kahalalide peptide that was totally synthesized.96 It is a cyclic depsipeptide composed of seven different amino acids (Gly, Thr, Pro, Leu, Phe, Ser, and Tyr) and the fatty acid 5-methylhexanoic acid (5-MeHex), which is also present in the structure of other members of the series. Two different strategies (A and B in Scheme 1) have been applied to accomplish the synthesis of kahalalide B (2). In strategy A, heptapeptide 175 was synthesized from the H-Gly-O-resin (174), which was produced from the commercially available chlorotrityl chloride resin (166) first by a sequential attachment of L-Thr, L-Pro, D-Leu, L-Phe, D-Ser, and L-Tyr derivative using Fmoc/t-Bu stragety and DIPCDI/HOBt as the coupling reagent. This was followed by capping with 5-methylhexanoc acid at the N-terminus. Cleavage of the resin from 175 with a TFA/DCM mixture (1:99) afforded the linear peptide 176, which was subjected to macrocyclization using 1H-benzotriazol-1-yloxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP)-DI-PEA. After removal of side chain protection with a TFA/H2O mixture (95:5), kahalalide B (2) was produced in 16% yield. In strategy B, there were some different points in the synthesis of kahalalide B (2). First, the limited incorporation of the first amino acid of the sequence was performed with Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH in the presence of DIEA. In contrast, in strategy A, the first amino acid was incorporated by using Fmoc-Gly-OH. Second, in strategy A, cyclization (the step between 176 and 177) was conducted in solution through the ester bond between the carboxyl group of Gly and the side chain hydroxyl of D-Ser, but in strategy B, the ester bond was formed on the solid phase and the cyclization (the step between 181 and 2) occurred through an amide bond between the carboxyl group of Thr and the amine group of Gly (see Scheme 1). Finally, the cyclization step was performed at a concentration of 10−3 M with PyBOP-DIEA (3.6 equiv) in DMF for 23 h (strategy A) or 1 h (strategy B). The lower nucleophilicity of the hydroxyl compared to that of the amine probably led to the difference in time for the cyclization step. Thus, strategy B is better than strategy A. The synthesis of kahalalide B (2) was achieved on a solid support, and this strategy should be useful for the synthesis of other cyclodepsipeptides.

Scheme 1.

5.2. Total Synthesis of KF

Several synthetic strategies have been successfully developed for the total synthesis of KF (6) (Table 5). The first successful synthesis of KF (6) (Scheme 2) is the linear solid phase synthesis.27 This methodology involves elongation of the synthetic chain on the solid phase. With the linear peptide in hand, cyclization in solution follows, and finally, deprotection allows preparation of the natural compound in a straightforward manner. Moreover, the solid phase methodology is easy to scale up and could be applied to generatea wide variety of new analogues. The Fmoc/t-Bu strategy and 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin allowed cleavage of the peptide under mild acidic conditions. Next, amino acid D-allo-Thr and the Thr precursor of (Z)-Dhb were both introduced without protection of the hydroxyl function. For the formation of all the amide bonds, N-[(dimethylamino)-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridin-1-ylmethylene]-N-methylmethanaminium hexafluorophosphate N-oxide (HATU) was used. The alloc group was removed under standard conditions before the peptide was deprotected from the resin. The cyclization reaction was then performed with benzotriazol-1-yl-N-oxy-tris(pyrrolidino)phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP) using DMF as a solvent. Finally, the deprotection of the Boc group afforded the natural product KF (6).

Table 5.

Synthesis of KF Analogues following Scheme 2

| analogue | step | residue replaced | residue incorporated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | [Etg2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-Etg-OH 2 |

| 26 | [d-Etg2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-d-Etg-OH 2 |

| 27 | [(Z)-Dhf2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-d/l-Phe-OH 2 |

| 28 | [dha2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-Ser-OH |

| 29 | [d-Thr2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-d-Thr-OH 2 |

| 30 | [d-allo-Thr2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Thr-OH 2 |

| 31 | [Gly2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-Gly-OH |

| 32 | [Aib2]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Thr-OH 2 | Fmoc-Aib-OH |

| 33 | [Trp3]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Trp-OH |

| 34 | [hCh3]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-hCh-OH |

| 35 | [Phe(3,4-Cl2)3,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(3,4-Cl2)-OH |

| 36 | [Phe(F5)3,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(F5)-OH |

| 37 | [Phe(4-I)3,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(4-I)-OH |

| 38 | [Phe(4-NO2)3,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(4-NO2)-OH |

| 39 | [Phe(4-F)3,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(4-F)-OH |

| 40 | [Tyr(Me)3,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Tyr(Me)-OH |

| 41 | [Thi3,4(S)-MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Thi-OH |

| 42 | [Tic3,4(S)-MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Tic-OH |

| 43 | [Tyr3,4(S)-MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Tyr(t-Bu)-OH |

| 44 | [Oic3,4(S)-MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Oic-OH |

| 45 | [NMePhe3,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-NMe-Phe-OH |

| 46 | [Phe(2-Cl)3]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(2-Cl)-OH |

| 47 | [Phe(3-Cl)3]-KF | A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(3-Cl)-OH |

| 48 | [Phe(4-Cl)3]-KF | A4 | 4(S)-MeHex 14 | 5-MeHex |

| A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(4-Cl)-OH | ||

| 49 | [Phe(3,4-F2)3]-KF | A4 | 4(S)-MeHex 14 | 5-MeHex |

| A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(3,4-F2)-OH | ||

| 50 | [NaI3]-KF | A4 | 4(S)-MeHex 14 | 5-MeHex |

| A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-NaI-OH | ||

| 51 | [Bip3]-KF | A4 | 4(S)-MeHex 14 | 5-MeHex |

| A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Bip-OH | ||

| 52 | [Phg3]-KF | A4 | 4(S)-MeHex 14 | 5-MeHex |

| A5 | Fmoc-Phe-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phg-OH | ||

| 53 | [Val4]-KF | B1 | Fmoc-DVal-OH 1 | Fmoc-Val-OH |

| 54 | [d-Dapa6]-KF | B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Thr-OH 6 | Fmoc-d-Dapa |

| 55 | [D-Thr6]-KF | B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Thr-OH 6 | Fmoc-d-Thr-OH |

| 56 | [d-Ser6]-KF | B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Thr-OH 6 | Fmoc-d-Ser-OH |

| 71 | [Nε(Me)3-Lys8,4(S)-MeHex14]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH |

| B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4(S)-MeHex | ||

| – | additional step | DIPEA/MeI | ||

| 72 | [Lys8]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH |

| 73 | [Glu8]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | Fmoc-Glu(t-Bu)-OH |

| B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 7 | none | ||

| 75 | [Orn(NδTfa)8,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | B7 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4(S)-MeHex |

| – | additional step | TFA/DIPEA | ||

| 76 | [Orn(NδTfa)8,Thr(OTfa)12,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | B7 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4(S)-MeHex |

| – | additional step | TFA/DCM (1:1), 3 days | ||

| 77 | [Thr(OTfa)12,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | B7 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4(S)-MeHex |

| – | additional step | TFA/DCM (1:1), 3 days | ||

| 78 | [nod-allo-Ile7,noOrn8,noD-Pro9,noD-Val10,noVal11, noThr12,noD-Val13]-KF |

B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 7 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 10 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | none | ||

| 79 | [noOrn8]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | none |

| 80 | [noOrn8,nod-Pro9]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-D-Pro-OH 9 | none | ||

| 81 | [noOrn8,nod-Pro9,nod-Val10]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 10 | none | ||

| 82 | [noOrn ,nod-Pro9,nod-Val10,noVal11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 10 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | none | ||

| 83 | [noOrn8,nod-Pro9,nod-Val10,noVal11,noThr12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 10 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-Val 11 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | none | ||

| 84 | [noOrn8,nod-Pro9,nod-Val10, noVal11,noThr12,nod-Val13]-KF |

B3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 10 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | none | ||

| 85 | [noVal11,noThr12,noD-Val13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | none | ||

| 86 | [Pro9, 4(S)MeHex14]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | Fmoc-Pro-OH |

| 87 | [d-Pip9,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | Fmoc-d-Pip-OH |

| 88 | [d-Tic9,4(S)MeHex14]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | Fmoc-d-Tic-OH |

| 89 | [5(R)-Ph-Pro9,4(S)-MeHex14]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | Fmoc-5(R)-Ph-Pro-OH |

| 90 | [Val10,d-Val11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 10 | Fmoc-Val-OH |

| B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH | ||

| 91 | [hCh11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-hCh-OH |

| 92 | [hCh11,d-Cha13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-hCh-OH |

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Cha-OH | ||

| 93 | [d-Cha13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Cha-OH |

| 94 | [Gly11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Gly-OH |

| 95 | [Phe11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Phe-OH |

| 96 | [Ala11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Ala-OH |

| 97 | [Leu11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Leu-OH |

| 98 | [d-Val11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH |

| 99 | [Pro11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Pro-OH |

| 100 | [Gln11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Gln-OH |

| 101 | [Orn11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH |

| 102 | [Thr11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH |

| 103 | [Glu11]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-Glu(O-t-Bu)-OH |

| 106 | [Gly12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Gly-OH |

| 107 | [Phe12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Phe-OH |

| 108 | [Ala12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Ala-OH |

| 109 | [Leu12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Leu-OH |

| 110 | [d-Thr12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-d-Thr(t-Bu)-OH |

| 111 | [Pro12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Pro-OH |

| 112 | [Gln12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Gln-OH |

| 113 | [Orn12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH |

| 114 | [Glu12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Glu(O-t-Bu)-OH |

| 115 | [Val12]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-Val-OH |

| 116 | [Gly13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-Gly-OH |

| 117 | [d-Phe13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Phe-OH |

| 118 | [d-Ala13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Ala-OH |

| 119 | [d-Leu13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Leu-OH |

| 120 | [Val13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-Val-OH |

| 121 | [d-Pro13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH |

| 122 | [d-Thr13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Thr(t-Bu)-OH |

| 123 | [d-Glu13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Glu(O-t-Bu)-OH |

| 124 | [d-Gln13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Gln-OH |

| 125 | [Orn13]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-d-Orn(Boc)-OH |

| 126 | [no5-MeHex14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | none |

| 127 | [Ac14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | AcOH |

| 128 | [Tfa14]-KF |

B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | TFA |

| 129 | [But14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | But-OH |

| 130 | [3-MeBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 3-MeBut-OH |

| 131 | [3,3-dMeBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 3,3-dMeBut-OH |

| 132 | [4-MePen14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4-MePen-OH |

| 133 | [(c/t)MecHex14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | (c/t)-MecHex-OH |

| 134 | [4(R)-MeHex14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4(R)-MeHex-OH |

| 135 | [Hep14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Hep-OH |

| 136 | [6,6-dFHep14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 6,6-dFHep-OH |

| 137 | [Pfh14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Pfh-OH |

| 138 | [Oct14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Oct-OH |

| 139 | [Und14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Und-OH |

| 140 | [Palm14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Palm-OH |

| 141 | [Icos14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Icos-OH |

| 142 | [2,4-hexadie14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 2,4-hexadie-OH |

| 143 | [Bza14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Bza-OH |

| 144 | [p-MeBza14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | p-MeBza-OH |

| 145 | [p-TflBza14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | p-TflBza-OH |

| 146 | [Pipe14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Pipe-OH |

| 147 | [3,5-dFPhAc14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 3,5-dFPhAc-OH |

| 148 | [p-TflPhAc14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | p-TflPhAc-OH |

| 149 | [p-TflCinn14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | p-TflCinn-OH |

| 150 | [4-dMeaBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4-dMeaBut-OH |

| 151 | [4-GuBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4-GuBut-OH |

| 152 | [6-Ohep14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 6-Ohep-OH |

| 153 | [4-Ac-OBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4-Ac-OBut |

| 154 | [4-OHBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4-OHBut-OH |

| 155 | [4-(4-AcOBut)OBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | 4-(4-Ac-OBut)OBut-OH |

| 156 | [d-allo-IleiBut14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH |

| additional step | iBut-OH | |||

| 157 | [Lit14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Lit-OH |

| 158 | [Lit(OTfa)14]-KF | B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Lit-OH |

| B7 | – | trifluoroacetylion | ||

| 159 | [d-Val1,d-Phe3,Val4,allo-Ile5,allo-Thr6,allo-Ile7, d-Orn8,Pro9,Val10,d-Val11,d-Thr12,Val13]-KF |

A1 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 4 | Fmoc-Val-OH |

| A2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 5 | Fmoc-allo-Ile-OH | ||

| A2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Thr-OH 6 | Fmoc-allo-Thr-OH | ||

| A2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 7 | Fmoc-allo-Ile-OH | ||

| A3 | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH 8 | Fmoc-d-Orn(Boc)-OH | ||

| A3 | Fmoc-d-Pro-OH 9 | Fmoc-Pro-OH | ||

| A3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 10 | Fmoc-Val-OH | ||

| A4 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH | ||

| A4 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | Fmoc-d-Thr(t-Bu)-OH | ||

| A4 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | Fmoc-Val-OH | ||

| 160 | [d-Cha4,d-Cha4,d-Cha7]-KF | B1 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 4 | Fmoc-d-Cha-OH |

| B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 5 | Fmoc-d-Cha-OH | ||

| B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 7 | Fmoc-d-Cha-OH | ||

| 161 | [d-Val5,d-Va7]-KF | B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 5 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH |

| B2 | Fmoc-d-allo-Ile-OH 7 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH | ||

| 162 | [Phe(3,4-Cl2)3,pCF3 Cinn14]-KF | 4 | 5-MeHex 14 | p-CF3 Cinn-OH |

| 5 | Fmoc-hCh-OH 3 | Fmoc-Phe(3,4-Cl2)-OH | ||

| 163 | [noVal11,noThr12,nod-Val13,Mst14]-KF | B3 | Fmoc-Val-OH 11 | none |

| B3 | Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH 12 | none | ||

| B3 | Fmoc-d-Val-OH 13 | none | ||

| B4 | 5-MeHex 14 | Mst-OH | ||

| 164 | [Thr(OTfa)12,Lit(OTfa)14]-KF | A4 | 5-MeHex 14 | LiOH |

| A7 | additional step | TFA/DCM (1:1) | ||

| 165 | [no5-MeHex14,N-(Hep)2-d-Val13]-KF | A4 | additional step | heptanaldehyde/NaBH3CN/DMF and AcOH (9:1) |

Scheme 2.

The original solid phase synthesis was based on an orthogonal protecting group scheme using a chlorotrityl chloride resin together with Fmoc and allyloxycabonyl (Alloc) as temporary protecting groups, and t-Bu and Boc for the side chain protection of Thr and Orn, respectively. In 2005, p-nitrobenzyloxycarbonyl (p-NZ) was used for the permanent protection of ornithine in the synthesis of derivatives of KF (6), which contains acid labile residues.95

Furthermore, several convergent strategies (scheme 3) have been developed for the synthesis of KF (6).98 Convergent strategies are defined as those in which peptide fragments are coupled to give the desired target molecule. The condensation of peptide fragments should lead to fewer problems in the isolation and purification of intermediates. The general convergent strategy for the synthesis of KF (6) included dividing the peptide into fragments, the N-terminal and the fragment containing the cycle. Four strategies were applied to prepare the three distinct N-components (Scheme 3). All four strategies were based on the solid phase synthesis of a branched peptide using a tri- and tetra-orthogonal protecting scheme and subsequent cyclization and deprotection of the N-terminal function in solution. In strategy I, pentapeptide 168 was formed from the Fmoc-D-Valresin, prepared from the resin (166) by a sequential incorporation of D-allo-Ile, D-allo-Thr, and D-allo-Ile derivatives by using the Fmoc/t-Bu strategy and a DIPCDI/HOBt mixture as the coupling reagent and the esterification of the β-hydroxyl group of D-allo-Thr with Alloc-Val-OH using a DIPCDI/DMAP mixture. The macrocyclization of 184 by the HOBt/DIPEA/DIPCDI mixture was followed by the deprotection of Fmoc or p-NZ groups to afford the N-component 185. The corresponding C-component 5-MeHex-D-Val-Thr(t-Bu)-Val-D-Val-D-Pro-OH was synthesized from the Fmoc-D-Pro-resin by a sequential attachment of D-Val, Thr, and D-Val derivatives using the Fmoc/t-Bu method and a DIPCDI/HOBt mixture as the coupling reagent and then being capped with 5-methylhexanoic acid at the N-terminus. Finally, the condensation of the N-component 185 and the corresponding C-component using a PyAOP/DIEA mixture yielded the product KF (6). In strategy 2, the synthesis of 185 started with a form of 186 by the incorporation of Alloc-Phe-Z-Dhb-OH onto the resin 166. For chain elongation to the heptapeptide 187 from 186, five amino acids were sequentially attached. Ester linkage between 187 and Fmoc-Val-OH was formed by a DIPCDI/DIPEA mixture. The removal of the Fmoc group from 188 by using a TFA/CH2Cl2 mixture (1:99) yielded 189, which was followed by the cyclization and deprotection to afford 185. Here HOBt and DIPCDI were used for macrocyclization; Pd(PPh3)4 and PhSiH3 were applied to successfully remove the Alloc group, and SnCl2 was effective for removal of the p-NZ group. For strategies I and II, epimerization was not observed. In strategy III, the removal of the Alloc group of 168 by using Pd(PPh3)4 and PhSiH3 was followed by the attachment of Alloc-Phe-Z-Dhb-OH in the presence of HOBt and DIPCDI to afford 190. The Boc group was introduced as an Nα-amino protecting group of D-allo-Ile in 190 after the Fmoc and Alloc groups had been removed. 191 was subjected to macrocyclization using a HOBt/DIPEA/DIPCDI mixture and removal of the Boc group using a TFA/H2O mixture (19:1) to produce the second N-component 192, which was then condensed with the corresponding C-component in solution using a PyAOP/DIEA mixture to afford the final KF (6). In strategy IV, pentapeptide 193 was synthesized from 186 by a sequential attachment of D-Val, D-allo-Ile, and D-allo-Thr derivatives using the Fmoc/t-Bu method. The Boc group was used as an Nα-amino protecting group of D-allo-Thr in 193 to form 194, which was subjected to Fmoc-Val-OH coupling and the removal of the Fmoc group. The third N-component 196 was synthesized from 195 by macrocyclization using a HOBt/DIPEA/DIPCDI mixture and removal of the Boc group using a TFA/H2O mixture (19:1). The condensation of 196 with the corresponding C-component produced KF (6). Epimerization of the C-terminal amino acids of the C-component in strategies III and IV was measured (4% for the case of Orn in strategy III and >10% for D-allo-Ile in strategy IV). Among these four strategies depicted in Scheme 3 showed, strategies I and II are better than strategies III and IV because the C-terminal amino acid of the C-component is D-Pro, which prevents epimerization during the coupling of the fragment in solution. The advantage of strategy II over strategy I was the fact that smaller amounts of the precious Alloc-Phe-Z-Dhb-OH were used.

Scheme 3.

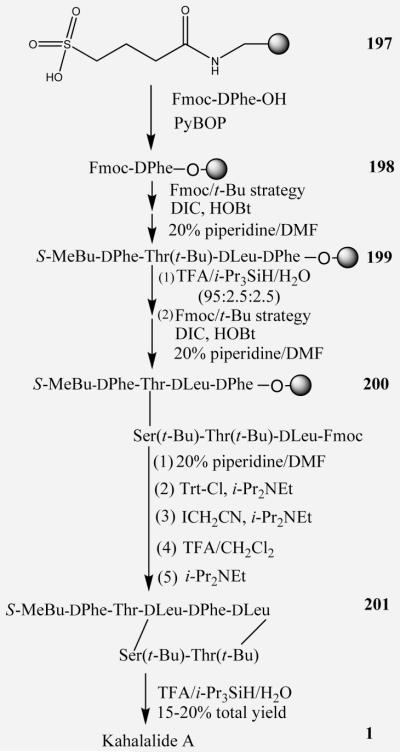

5.3. Total Synthesis of KA

As Scheme 4 shows, the total synthesis of kahalalide A (1) began with the attachment of Fmoc-D-Phe onto the commercially available sulfonamide resin (197) giving 198, which was incorporated with Fmoc-D-Leu, Fmoc-L-Thr(t-Bu), Fmoc-D-Phe, and (S)-2-methylbutyric acid to provide 199. Deprotection of the Thr side chain in 199 was followed by ester bond formation with Fmoc-L-Ser(t-Bu). An attachment of Fmoc-L-Thr(t-Bu) and Fmoc-D-Leu afforded the key linear heptapeptides 200. The safety-catch linker was then activated by sulfonamide alkylation with iodoacetonitrile, and macrocyclative cleavage of depsipeptide 201 into the solution resulted from trityl deprotection of the free amine. Acidic cleavage of the t-Bu ethers is the last step of the synthesis of kahalalide A (1) in 15-20% overall yield.

Scheme 4.

6. STRUCTURE-ACTIVITY RELATIONSHIP

6.1. Structure-Activity Relationship Study of KA

With the total synthesis successfully accomplished, Bourel-Bonnet et al. investigated the SAR of kahalalide A (1) by synthesizing kahalalide A analogues. The results highlighted the importance of the free Ser and Thr side chains and the constrained depsipeptide framework for biological activity. The methylbutyrate side chain is flexible and can be replaced with other hydrophobic groups, as evidenced by increased activity with hexanoate.97

6.2. Structure-Activity Relationship Study on KF and Its Analogues

Approximately 143 new KF analogues (Table 6 and Figure 3) have been successfully synthesized or semisynthesized by two groups to improve pharmacological properties and examine the role of each residue in the biological activity of KF (6) to examine the structure-activity relationship of KF (6).69,70 In 2007, our group obtained 10 new KF analogues (57-64, 104, and 105) by reaction of KF (6) as a starting point with diverse reactants through the amino group of Orn (acetylation with common coupling reagents) or the hydroxyl group of Thr.69

Table 6.

KF Analoguesa

| analogue Val1 | (Z)-Dhb2 | Phe3 |

d- Val4 |

d-allo- Ile5 |

d-allo- Thr6 |

d-allo- Ile7 |

Orn8 | d-Pro9 |

d- Val10 |

Val11 | Thr12 | d-Val13 | 5-MexHex14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Etg | |||||||||||||

| 26 | d-Etg | |||||||||||||

| 27 | (Z)-Dhf | |||||||||||||

| 28 | Dha | |||||||||||||

| 29 | d-Thr | |||||||||||||

| 30 | d-allo-Thr | |||||||||||||

| 31 | Gly | |||||||||||||

| 32 | Aib | |||||||||||||

| 33 | Trp | |||||||||||||

| 34 | hCh | |||||||||||||

| 35 | Phe(3,4-Cl2) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 36 | Phe(F5) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 37 | Phe(4-I) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 38 | Phe(4-NO2) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 39 | Phe(4-F) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 40 | Tyr(Me) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 41 | Thi | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 42 | Tic | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 43 | Tyr | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 44 | Oic | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 45 | N-MePhe | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 46 | Phe(2-Cl) | |||||||||||||

| 47 | Phe(3-Cl) | |||||||||||||

| 48 | Phe(4-Cl) | |||||||||||||

| 49 | Phe(3,4-F2) | |||||||||||||

| 50 | Nal | |||||||||||||

| 51 | Bip | |||||||||||||

| 52 | Phg | |||||||||||||

| 53 | Val | |||||||||||||

| 54 | d-Dapa | |||||||||||||

| 55 | d-Thr | |||||||||||||

| 56 | d-Ser | |||||||||||||

| 57 | Orn(4-FB) | |||||||||||||

| 58 | Orn(4-FB)2 | |||||||||||||

| 59 | Orn(4-PM) | |||||||||||||

| 60 | Orn(2-TM) | |||||||||||||

| 61 | Orn (2-TM)2 | |||||||||||||

| 62 | Orn(nHex) | |||||||||||||

| 63 | Orn(nHex)2 | |||||||||||||

| 64 | Orn(DEAC) | |||||||||||||

| 65 | Orn(tHex) | |||||||||||||

| 66 | Orn(TFB) | |||||||||||||

| 67 | Orn(cHP) | |||||||||||||

| 68 | Orn(Mosh) | |||||||||||||

| 69 | Orn(Fmoc-PEG) | |||||||||||||

| 70 | Orn(PEG) | |||||||||||||

| 71 | N-(Me)3-Lys | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 72 | Lys | |||||||||||||

| 73 | Glu | |||||||||||||

| 74 | Orn(Biot) | |||||||||||||

| 75 | Orn(NδTfa) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 76 | Orn(NδTfa) | Thr(OTfa) | 4 | |||||||||||

| 77 | Thr(OTfa) | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 78 | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | ||||||

| 79 | no | |||||||||||||

| 80 | no | no | ||||||||||||

| 81 | no | no | no | |||||||||||

| 82 | no | no | no | no | ||||||||||

| 83 | no | no | no | no | no | |||||||||

| 84 | no | no | no | no | no | no | ||||||||

| 85 | no | no | no | |||||||||||

| 86 | Pro | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 87 | d-Pip | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 88 | d-Tic | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 89 | 5(R)-Ph-Pro | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 90 | Val | d-Val | ||||||||||||

| 91 | hCh | |||||||||||||

| 92 | hCh | d-Cha | ||||||||||||

| 93 | d-Cha | |||||||||||||

| 94 | Gly | |||||||||||||

| 95 | Phe | |||||||||||||

| 96 | Ala | |||||||||||||

| 97 | Leu | |||||||||||||

| 98 | d-Val | |||||||||||||

| 99 | Pro | |||||||||||||

| 100 | Gln | |||||||||||||

| 101 | Orn | |||||||||||||

| 102 | Thr | |||||||||||||

| 103 | Glu | |||||||||||||

| 104 | Thr(Ac) | |||||||||||||

| 105 | Thr(Oxo) | |||||||||||||

| 106 | Gly | |||||||||||||

| 107 | Phe | |||||||||||||

| 108 | Ala | |||||||||||||

| 109 | Leu | |||||||||||||

| 110 | d-Thr | |||||||||||||

| 111 | Pro | |||||||||||||

| 112 | Gln | |||||||||||||

| 113 | Orn | |||||||||||||

| 114 | Glu | |||||||||||||

| 115 | Val | |||||||||||||

| 116 | Gly | |||||||||||||

| 117 | d-Phe | |||||||||||||

| 118 | d-Ala | |||||||||||||

| 119 | d-Leu | |||||||||||||

| 120 | Val | |||||||||||||

| 121 | d-Pro | |||||||||||||

| 122 | d-Thr | |||||||||||||

| 123 | d-Glu | |||||||||||||

| 124 | d-Gln | |||||||||||||

| 125 | d-Orn | |||||||||||||

| 126 | No | |||||||||||||

| 127 | Ac | |||||||||||||

| 128 | Tfa | |||||||||||||

| 129 | But | |||||||||||||

| 130 | 3-MetBut | |||||||||||||

| 131 | 3,3-dMeBut | |||||||||||||

| 132 | 4-MePen | |||||||||||||

| 133 | (c/t)-MeHex | |||||||||||||

| 134 | 4(R)-MeHex | |||||||||||||

| 135 | Hep | |||||||||||||

| 136 | 6,6-dFhep | |||||||||||||

| 137 | Pfh | |||||||||||||

| 138 | Oct | |||||||||||||

| 139 | Und | |||||||||||||

| 140 | Palm | |||||||||||||

| 141 | Icos | |||||||||||||

| 142 | 2,4-Hexadie | |||||||||||||

| 143 | Bza | |||||||||||||

| 144 | p-MeBza | |||||||||||||

| 145 | p-TflBza | |||||||||||||

| 146 | Pipe | |||||||||||||

| 147 | 3,5-dFPhAc | |||||||||||||

| 148 | p-TflPhAc | |||||||||||||

| 149 | p-TflCinn | |||||||||||||

| 150 | 4-dMeaBut | |||||||||||||

| 151 | 4-GuBut | |||||||||||||

| 152 | 6-Ohep | |||||||||||||

| 153 | 4-Ac-Obut | |||||||||||||

| 154 | 4-OHBut | |||||||||||||

| 155 | 4-(4-Ac-Obut)Obut | |||||||||||||

| 156 | d-allo-Ile-IBut | |||||||||||||

| 157 | Lit | |||||||||||||

| 158 | Lit(OTfa) | |||||||||||||

| 159 | d-Val | d-Phe | Val | allo-Ile | allo-Thr | allo-Ile | d-Orn | Pro | Val | d-Vald-Thr | Val | |||

| 160 | d-Cha | d-Cha | d-Cha | |||||||||||

| 161 | d-Val | d-Val | ||||||||||||

| 162 | Phe(3,4-Cl2) | p-TflCinn | ||||||||||||

| 163 | no | no | no | Mst | ||||||||||

| 164 | Thr(OTfa) | Lit(OTfa) | ||||||||||||

| 165 | N(Hep)2-d-Val | |||||||||||||

The chemical structure of each modification can be found in Figure 3. The numeral 4 in the 5-MeHex column indicates the presence of 4(S)-MeHex.

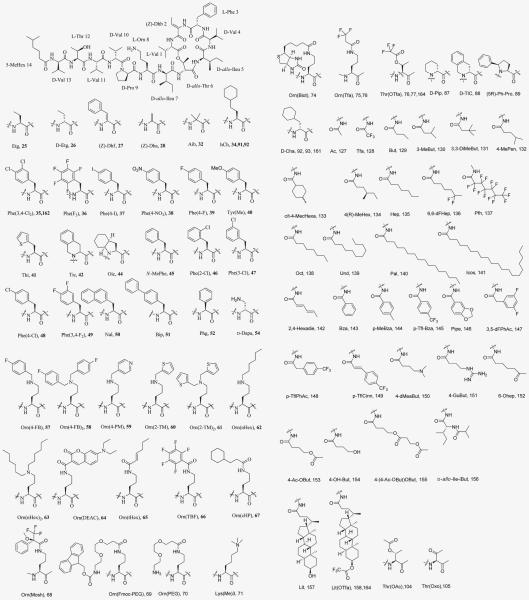

Figure 3.

Building blocks used for the substitution of residues in KF (6).

6.2.1. Semisynthetic Analogues of KF

In 2007, our group focused on the secondary alcohol of Thr and the primary amine of Orn as the key functional groups to modify from the bacterially produced natural products because they play a crucial role in the bioactivity of this class of compounds.69 For spectroscopic and bioassay comparison, we first converted KF (6) to kahalalide G (7) under mild basic conditions. Thus, KF (6) was subjected to hydrolysis in a H2O/MeOH mixture (2:1) in the presence of potassium carbonate at room temperature, causing catalytic cleavage of macrolactone to the target ring-opened product. Further studies continued with the acetylation of KF (6). Treatment of free base KF (6) with an excess 2:1 volumetric ratio of acetic anhydride to BF3,3 OEt2 at room temperature after 5 min led to major product (68%), monoacetate-KF (104). Addition of the Dess-Martin periodinane (DMP) to a solution of KF (6) in acetonitrile furnished the oxidation of the secondary alcohol to the corresponding oxo-KF (105) in good yield (75%). Some KF analogues were obtained by modification of the primary amine group on L-Orn to the related secondary amines as potential pharmacophores. KF (6) was reduced to the corresponding monoalkyl- or dialkyl-amino-KF by the stepwise reductive N-alkylation of the amino groups in the presence of a carboxyaldehyde and hydride reducing agent. This stepwise one-pot procedure includes the initial formation of the intermediate carbinol amine, which then dehydrates to form an imine. Then in situ reduction of this carbinol imine produces the alkylated amine. Sodium triacetoxyborohydride [NaBH(OAc)3] was used as the hydride reducing agent that offers mild borohydride reduction and exhibits remarkable selectivity because the steric and electron withdrawing effects of the three acetoxy groups stabilize the boron-hydrogen bond and are responsible for its mild reducing properties. The reductive alkylation of KF was best performed under optimized conditions by the exposure of parent molecule to 5 equiv of the known aldehyde in methanol for 30 min at room temperature prior to portionwise addition of 2 equiv of triacetoxyborohydride under the same conditions. The reaction time was designed from a few hours to a couple of days and gave the desired products (57-63) in good to very good yields (Scheme 5). Furthermore, one KF analogue (64) was simply synthesized by treatment of DEAC-carboxylic acid and KF (6) in the presence of EDC and HBTU in DMF at room temperature for 1 h.

Scheme 5.

In 2008, the Albericio group reported seven new KF semisynthetic analogues (65-70 and 74) by modifying the primary amine of L-Orn in KF (6).70 Compound 65 was easily obtained by adding DIPEA, tHex-OH, HOBt, and DIPCDI sequentially to a solution of KF (6) in a DMF/CH2Cl2 mixture (20:80) at 23 °C. The same procedure was applied to produce compounds 66-69 only by replacing tHex-OH with TFB-OH, cHP-OH, (þ)-MTPA, or Fmoc-PEG-OH. Compound 69 was dissolved in a piperidine/DMF mixture (20:80) and stirred at 23 °C for 30 min to produce compound 70 in 75% yield. In addition, KF (6), D-Biotine, and HATU were dissolved in anhydrous DCM under an Ar atmosphere, and NMM was added, yielding compound 74.

6.2.2. Synthetic Analogues of KF

Giralt, Albericio, and his co-workers synthesized ~125 novel KF analogues by solid phase synthesis (Scheme 2).70 The route is very similar to the total synthesis route of KF (6) with minor modifications. The whole route consists of seven steps, including the elongation of the synthetic chain on the solid phase, subsequent cyclization, and final deprotection in solution. The tetrapeptide resin 168 was synthesized from the D-Val resin 167, which was prepared from the commercially available chlorotrityl chloride resin (166), by a sequential attachment of D-allo-Ile, D-allo-Thr, and D-allo-Ile derivatives using the Fmoc/t-Bu strategy and a DIPCDI/HOBt mixture as the coupling reagent. An ester linkage between 166 and Allo-Val-OH was produced by using diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIPCDI) in the presence of DMAP. For elongation of the chain to the decapeptide 170 from 168, six amino acids were sequentially attached and capped with 5-methylhexanoic acid at the N-terminus. Construction of (Z)-Dhb was conducted via two methods: (A) after side chain elongation from 170 to the tridecapeptide 171, stereoselective formation of the (Z)-Dhb residue on the resin by Fukase’s method using EDCI and cuprous chloride and (B) direct introduction of the dipeptide, Alloc-Phe-(Z)-Dhb-OH, to 172 with a DIPCDI/HOAt mixture. The Alloc group in 172 was deprotected with Pd(PPh3)4 and phenylsilane, and cleavage from the resin with a TFA/CH2Cl2 mixture (1:99) afforded the linear depsipeptide 173, which was subjected to macrocyclization using a DIPCDI/HOBt/DIEA mixture, after removal of side chain protection with a TFA/H2O mixture (19:1). The yield of KF (6) was 10-14%. In Scheme 2, two alternative routes for incorporating the amino acid Z-didehydroaminobutyric acid are listed. Method B was chosen for most analogues. These 125 KF analogues (Figure 1 and Table 6) were synthesized following the procedure described for KF (6) described in Scheme 2, and antitumor activities of these compounds are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Activity Data (GI50) of KF Analogues (micromolar)

| DU-145 | LN-caP | IGROV | IGROV ET | SK-BR 3 | MEL-28 | A-549 | K-562 | PANC-1 | HT-29 | LOVO | LOVO DOX | HELA | HELA APL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 1.93 | 1.77 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| 25 | 3.05 | – | 2.81 | 1.64 | – | 4.48 | 4.97 | 21.60 | 3.09 | 7.35 | 3.03 | 2.72 | 4.76 | 7.16 |

| 26 | 3.26 | – | 2.72 | 1.64 | – | 3.10 | 3.23 | 7.02 | 4.09 | 3.66 | 2.63 | 1.76 | 4.28 | 7.16 |

| 27 | 1.39 | – | 2.78 | 2.12 | 0.60 | 4.69 | 1.50 | – | 4.54 | 5.13 | 0.84 | – | 1.50 | 1.34 |

| 28 | 1.11 | 1.44 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 2.47 | 4.12 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 1.66 | 0.89 |

| 29 | 18.40 | – | – | – | – | 11.70 | 11.50 | – | – | 8.52 | – | – | – | – |

| 30 | 7.53 | – | 4.86 | 3.48 | 6.15 | 33.10 | 4.49 | – | 4.88 | 11.80 | 3.44 | – | 8.58 | 7.52 |

| 31 | 1.41 | 2.74 | 1.64 | 0.72 | 1.66 | 1.39 | 1.63 | 2.53 | 4.16 | 2.26 | 1.84 | 0.83 | 1.75 | 1.83 |

| 32 | 1.64 | 3.64 | 1.79 | 1.08 | 2.13 | 2.18 | 4.15 | 5.71 | 4.08 | 2.35 | 2.32 | 1.59 | 4.57 | 2.79 |

| 33 | 0.83 | 2.06 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 3.42 | 1.61 | 4.84 | 7.69 | 1.05 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 1.36 | 1.36 |

| 34 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 1.02 | 0.76 | 1.42 | 1.12 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.32 |

| 35 | 0.27 | – | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.11 | 6.47 | 2.09 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 1.02 |

| 36 | 1.37 | 0.50 | 2.07 | 2.03 | 0.56 | 1.28 | 1.85 | – | 2.11 | 1.09 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 3.75 | 1.45 |

| 37 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.67 | 1.19 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.23 | – | 1.20 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.60 | 0.31 |

| 38 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 1.05 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.56 | – | 1.29 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.78 | 0.57 |

| 39 | 0.89 | 0.51 | 0.81 | 0.97 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 1.01 | – | 1.46 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.96 | 0.74 |

| 40 | 0.86 | – | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 1.19 | 0.53 | 3.55 | 3.12 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.77 | 1.01 |

| 41 | 1.38 | – | 2.44 | 1.71 | 0.82 | 1.58 | 1.76 | 4.92 | 5.98 | 1.29 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 1.59 | 1.77 |

| 42 | 4.16 | – | 3.33 | 2.43 | 2.30 | 1.62 | 1.75 | 4.89 | 6.79 | 1.89 | 2.82 | 0.72 | 1.92 | 2.06 |

| 43 | 6.89 | – | 3.96 | 3.39 | 2.10 | 2.37 | 5.09 | 4.92 | 6.80 | 2.21 | 1.83 | 1.03 | 3.62 | 6.29 |

| 44 | 1.46 | – | 1.82 | 1.59 | 0.70 | 1.15 | 1.46 | 4.75 | 2.58 | 1.66 | 1.21 | 0.36 | 1.56 | 1.26 |

| 45 | 1.23 | – | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 1.35 | 1.30 | 2.14 | 1.92 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 1.11 |

| 46 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 1.85 | 1.51 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.31 |

| 47 | 0.10 | – | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| 48 | 0.11 | – | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 1.14 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.22 |

| 49 | 0.04 | – | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| 50 | 0.05 | – | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| 51 | 0.17 | – | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 3.22 | 1.24 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.48 |

| 52 | 0.87 | – | 0.50 | 0.81 | 0.44 | 1.11 | 1.09 | 1.81 | 1.66 | 8.20 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 1.73 | 1.62 |

| 53 | 4.99 | – | 5.65 | 1.22 | – | 7.45 | 4.98 | 37.40 | 1.68 | 16.40 | 5.49 | 15.50 | 3.87 | 7.17 |

| 54 | 8.80 | 6.88 | 9.55 | 5.68 | 8.66 | 6.40 | 9.48 | 9.66 | 9.71 | 13.20 | 11.50 | – | 7.45 | 7.04 |

| 55 | 32.00 | 19.30 | 73.20 | 3.76 | 8.20 | 8.20 | 7.16 | 25.30 | 586.00 | 17.60 | 16.40 | 6.03 | 17.70 | 9.52 |

| 56 | 5.04 | 3.37 | 16.70 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 1.90 | 1.44 | 19.00 | 267.00 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 3.53 | 1.93 |

| 65 | 0.66 | – | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 1.24 | 1.67 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.50 |

| 66 | 0.73 | – | 0.18 | 0.33 | – | 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.58 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.49 |

| 67 | 0.08 | – | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

| 68 | 0.89 | – | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.11 | 1.55 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| 69 | 0.02 | – | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| 70 | 0.74 | 1.82 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 1.25 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 0.52 |

| 71 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 1.11 | 1.39 | 1.84 | 4.16 | 0.79 | 0.36 | – | 0.94 | 1.11 |

| 72 | 1.29 | 1.33 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.39 | 1.47 | 1.44 | 9.35 | 5.11 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.51 |

| 73 | 21.70 | 1.88 | 1.95 | 3.54 | – | 5.89 | 10.90 | 3.32 | 2.50 | 2.67 | 0.79 | 7.95 | – | – |

| 74 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.37 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 4.80 | 1.99 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.99 |

| 75 | 1.33 | 1.46 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 1.91 | 1.14 | 3.75 | 3.80 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 1.21 |

| 76 | 1.46 | 1.14 | 0.37 | 0.77 | 0.33 | 17.60 | 1.23 | 3.83 | 2.38 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.85 |

| 77 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 1.43 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.50 |

| 78 | 5.10 | – | 14.00 | 4.40 | – | 14.50 | 9.71 | 73.00 | 4.35 | 32.00 | 14.90 | 30.20 | 0.74 | 14.00 |

| 79 | 3.67 | – | – | – | – | 3.67 | 3.67 | – | – | 3.67 | – | – | – | – |

| 80 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 23.00 | – | – | 9.89 | – | – | – | – |

| 81 | 4.30 | – | – | – | – | 4.30 | 4.30 | – | – | 4.30 | – | – | – | – |

| 82 | 9.36 | – | – | – | – | 9.36 | 9.36 | – | – | 9.36 | – | – | – | – |

| 83 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 50.10 | – | – | 162.00 | – | – | – | – |

| 84 | 11.50 | – | – | – | – | 11.50 | 11.50 | – | – | 11.50 | – | – | – | – |

| 85 | 69.40 | 9.85 | 10.70 | 11.60 | – | 8.41 | 36.60 | 3.48 | 2.92 | 25.60 | 19.10 | 25.00 | – | – |

| 86 | 9.38 | 21.30 | 7.57 | 5.00 | – | 6.48 | 3.36 | 8.22 | 7.69 | 7.56 | 11.50 | 13.20 | 6.60 | 4.99 |

| 87 | 2.28 | 5.79 | 1.39 | 0.89 | – | 1.59 | 0.80 | 6.45 | 7.62 | 1.16 | 2.25 | 1.22 | 3.08 | 1.51 |

| 88 | 2.39 | 4.33 | 1.52 | 1.06 | – | 3.63 | 1.43 | 7.90 | 7.38 | 1.32 | 2.62 | 2.29 | 3.40 | 3.64 |

| 89 | 8.93 | 10.30 | 7.20 | 3.05 | – | 6.16 | 3.19 | 7.82 | 5.17 | 7.19 | 7.33 | 12.60 | 6.28 | 4.75 |

| 90 | 3.39 | – | – | – | – | 3.39 | 3.39 | – | – | 3.39 | – | – | – | – |

| 91 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 1.04 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.46 |

| 92 | 3.30 | 3.38 | 2.39 | 3.03 | 2.06 | 3.18 | 3.60 | 1.79 | 2.90 | 2.90 | 2.81 | 1.21 | 2.95 | 4.34 |

| 93 | 1.41 | 2.98 | 1.27 | 1.09 | 0.79 | 1.73 | 1.97 | 2.10 | 7.15 | 2.01 | 2.09 | 0.83 | 1.30 | 1.45 |

| 94 | 8.95 | 3.05 | 6.44 | 5.78 | 19.00 | 6.51 | 9.65 | 2.57 | 7.21 | 13.50 | 10.70 | – | 7.58 | 7.16 |

| 95 | 0.61 | 0.86 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 1.74 | 2.54 | 0.27 | 0.29 | – | 0.43 | 0.82 |

| 96 | 3.90 | 2.80 | 2.00 | 1.25 | 3.25 | 3.45 | 3.73 | 4.32 | 9.79 | 2.59 | 2.68 | – | 3.10 | 3.27 |

| 97 | 0.94 | 1.03 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.96 | 1.28 | 2.10 | 3.29 | 0.61 | 0.31 | – | 1.02 | 0.94 |

| 98 | 3.13 | 2.44 | 2.09 | 1.39 | 3.69 | 6.34 | 5.09 | 4.29 | 4.43 | 4.84 | 3.31 | – | 5.02 | 3.40 |

| 99 | 8.72 | 3.47 | 9.47 | 5.63 | 18.50 | 6.34 | 9.40 | 9.57 | 7.99 | 13.10 | 16.10 | – | 7.39 | 6.98 |

| 100 | 8.54 | 3.12 | 9.27 | 5.51 | 18.10 | 6.21 | 8.07 | 9.38 | 7.24 | 12.90 | 14.30 | – | 7.23 | 6.83 |

| 101 | 1.23 | 1.76 | 1.75 | 1.35 | 4.46 | 1.52 | 2.92 | 0.22 | 1.73 | 4.61 | 3.61 | 7.59 | 1.28 | 1.11 |

| 102 | 7.56 | 5.41 | 5.18 | 1.91 | 2.07 | 7.72 | 7.56 | 9.83 | 5.51 | 11.00 | 2.97 | 2.99 | 6.47 | 7.00 |

| 103 | 7.48 | 5.30 | 9.13 | 4.69 | 15.20 | 7.58 | 7.41 | 9.64 | 8.78 | 19.30 | 16.30 | 15.60 | 7.69 | 6.87 |

| 106 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 2.39 | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| 107 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| 108 | 1.42 | 1.38 | 2.01 | 1.23 | 5.82 | 1.24 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 1.16 | 1.67 | 2.05 | 1.08 | 1.27 | 1.28 |

| 109 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.43 | 1.27 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 1.06 | 1.17 |

| 110 | 5.21 | 4.17 | 8.12 | 9.19 | 10.70 | 6.94 | 6.84 | 1.93 | 3.14 | 18.50 | 17.00 | 11.60 | 7.48 | 8.00 |

| 111 | 4.84 | 6.62 | 4.52 | 7.41 | 3.08 | 2.44 | 1.61 | 1.48 | 5.14 | 4.63 | 4.66 | 2.86 | 2.10 | 2.95 |

| 112 | 0.91 | – | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.90 | 1.74 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 1.81 | 1.70 |

| 113 | 6.67 | 6.75 | 4.70 | 7.62 | 2.88 | 5.27 | 3.27 | 1.62 | 8.05 | 5.90 | 4.94 | 2.88 | 3.42 | 6.67 |

| 114 | 2.48 | 1.07 | 0.86 | 1.13 | 1.92 | 4.83 | 1.63 | 8.13 | 4.12 | 1.31 | 1.71 | 9.65 | 2.55 | 2.06 |

| 115 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.72 | 1.12 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.32 |

| 116 | 5.69 | – | 10.50 | 5.36 | – | 6.95 | 0.72 | 38.50 | 0.50 | 10.90 | 8.76 | 11.10 | 0.67 | 7.37 |

| 117 | 3.90 | 2.28 | 2.01 | 2.24 | 2.34 | 2.64 | 2.65 | 3.40 | 5.44 | 2.34 | 2.62 | – | 2.21 | 1.79 |

| 118 | 1.81 | – | 2.13 | 1.61 | – | 1.99 | 1.46 | 7.41 | 1.66 | 3.03 | 1.98 | 0.80 | 1.03 | 1.68 |

| 119 | 1.34 | 1.79 | 1.05 | 1.31 | – | 1.09 | 1.92 | 2.72 | 2.91 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 2.09 | 1.00 |

| 120 | 0.55 | 0.85 | 1.53 | 2.89 | – | 1.00 | 1.33 | 0.31 | 1.51 | 0.64 | 1.30 | 1.76 | 2.31 | 1.04 |

| 121 | 2.06 | 1.16 | 2.49 | 4.70 | – | 1.05 | 2.83 | 1.31 | 2.75 | 5.16 | 4.57 | 3.51 | 2.89 | 1.18 |

| 122 | 1.47 | 1.95 | 1.17 | 1.00 | – | 1.22 | 1.55 | 8.51 | 3.91 | 1.06 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 2.03 | 1.04 |

| 123 | 2.84 | – | 2.01 | 1.31 | – | 3.73 | 3.25 | 7.02 | 5.31 | 2.91 | 1.95 | 2.03 | 2.94 | 2.91 |

| 124 | 1.46 | – | 1.57 | 1.33 | – | 1.34 | 0.23 | 6.80 | 0.17 | 2.30 | 1.46 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 2.42 |

| 125 | 1.16 | 0.85 | 1.13 | 1.03 | 1.72 | 1.14 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 1.42 | 0.77 | 2.30 | 2.04 | 1.37 | 1.10 |

| 126 | 5.98 | – | 11.10 | 4.01 | – | 8.05 | 5.39 | 40.50 | 5.49 | 17.80 | 9.46 | 16.70 | 5.16 | 7.75 |

| 127 | 7.11 | – | – | – | – | 7.11 | 7.11 | – | – | 7.11 | – | – | – | – |

| 128 | 3.42 | – | – | – | – | 6.84 | 6.84 | – | – | 3.42 | – | – | – | – |

| 129 | 1.74 | – | – | – | – | 3.48 | 3.48 | – | – | 1.74 | – | – | – | – |

| 130 | 2.07 | – | 2.25 | 1.36 | – | 1.98 | 1.68 | 7.79 | 8.47 | 2.98 | 1.63 | 0.88 | 2.09 | 2.33 |

| 131 | 0.34 | – | – | – | – | 3.42 | 1.71 | – | – | 0.34 | – | – | – | – |

| 132 | 0.34 | – | – | – | – | 3.42 | 0.34 | – | – | 0.34 | – | – | – | – |

| 133 | 0.69 | 1.07 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 2.94 | 2.66 | 0.55 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.63 |

| 134 | 1.69 | 2.98 | 0.83 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 2.01 | 1.69 | 2.07 | 8.01 | 0.73 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 2.33 | 1.28 |

| 135 | 0.85 | 1.09 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.81 | 1.18 | 2.74 | 2.36 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.97 | 0.78 |

| 136 | 4.52 | 1.84 | 1.33 | 0.99 | – | 2.94 | 2.03 | 2.96 | 2.04 | 1.96 | 0.44 | 1.81 | – | – |

| 137 | 0.53 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.29 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 2.32 | 0.51 | 1.16 | 0.29 | 0.96 | 0.60 |

| 138 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.93 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 2.83 | 0.58 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.95 | 0.53 |

| 139 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 1.67 | 1.63 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.24 |

| 140 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.33 |

| 141 | 15.70 | 1.65 | 5.17 | 4.69 | 3.40 | 1.89 | 1.88 | 9.14 | 1.79 | 3.95 | 3.81 | – | 5.44 | 1.52 |

| 142* | 6.85 | – | – | – | – | 6.85 | 3.43 | – | – | 0.69 | – | – | – | – |

| 143 | 1.21 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.87 | 1.12 | 1.32 | 0.43 | 5.38 | 1.34 | 0.35 | – | 1.21 | 1.04 |

| 144 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 1.09 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 2.92 | 0.61 | 0.33 | – | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| 145 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.84 | 0.20 | 9.18 | 1.84 | 0.22 | 0.25 | – | 0.35 | 0.52 |

| 146 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.64 | – | – | 0.41 | – | – | – | – |

| 147 | 1.84 | 1.65 | 1.37 | 0.89 | 1.27 | 2.34 | 1.62 | 9.29 | 7.73 | 1.72 | 0.79 | – | 1.41 | 2.02 |