Abstract

Background

Intravenous plasma administration has been recommended in healthy or sick calves with failure of passive immunity.

Hypothesis

IV administered plasma‐derived immunoglobulin G (IgG) undergoes increased catabolism as reflected by a rapid decrease in serum IgG concentration with an increase in fecal IgG concentrations within 48 h.

Animals

Thirty newborn Jersey calves. Fifteen were fed colostrum (CL group) and 15 were given bovine plasma IV (PL group).

Materials and Methods

Randomized clinical trial. Calves in the CL group were fed 3 L of colostrum once, by oroesophageal tubing. Calves in the PL group were given plasma IV at a dosage of 34 mL/kg. Serum and fecal samples were collected at 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 48 h, 5 d, and 7 d. Serum and fecal IgG concentrations were determined by radial immunodiffusion.

Results

Calves in the CL group maintained serum IgG concentrations consistent with adequate transfer of immunity (≥1,000 mg/dL) throughout the study period. Calves in the PL group achieved median IgG concentrations of ≥1,000 mg/dL at 6 h but the concentrations were <1,000 mg/dL by 12 h. Calves in the PL group were 5 times more likely to experience mortality compared to the CL group (hazard ratio = 5.01). Fecal IgG concentrations were not different between the 2 groups during the first 48 h (P > .05).

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Catabolism of plasma derived IgG occurs rapidly during the first 12 h after transfusion. Fecal excretion did not explain the fate of the plasma derived IgG.

Keywords: Cattle, Immunity, Mortality, Passive

Abbreviations

- CL

colostrum group

- FPI

failure of passive immunity

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PL

plasma group

- SRID

single radial immunodiffusion

Failure of passive immunity (FPI) resulting from inadequate colostral immunoglobulin intake in calves is a cause of immunodeficiency. Failure of passive immunity is a significant risk factor for morbidity and mortality from diseases of calves including diarrhea and pneumonia.1, 2 In clinical settings, IV administration has been recommended as part of medical management of healthy or sick calves with FPI, that >24 h because colostral immunoglobulin G (IgG) absorption has ceased.3, 4, 5 A recent study4 evaluating serum IgG concentrations after IV plasma administration at the recommended dosage of 30 mL/kg5 indicated that the majority of calves did not achieve serum IgG concentrations consistent with adequate transfer of immunity (ie, serum IgG ≥1,000 mg/dL)6 at 48 h of age. A limitation of this study4 was that serum IgG concentrations were not evaluated until 48 h after plasma transfusion. Thus, metabolism of IgG before 48 h was not determined. In studies of humans, suggested reasons for increased catabolism of IV administered IgG include formation of IgG aggregates during processing of plasma. The IgG aggregates result in activation of complement leading to increased catabolism followed by fecal and urinary excretion of plasma‐derived immunoglobulins.7

In calves, excretion of IV administered plasma derived IgG is predominantly through feces.6 Currently, studies evaluating metabolism of plasma derived IgG in cattle are lacking. In clinical practice, it is assumed, that healthy or sick neonatal calves with FPI that are given plasma IV, at the recommended dosage of 20–40 mL/kg4 will achieve and maintain serum IgG concentrations consistent with adequate transfer of immunity (ie, serum IgG concentrations ≥1,000 mg/dL).6 We hypothesized that IV administered plasma derived IgG would undergo increased catabolism as reflected by a rapid decrease in serum IgG concentration and an increase in fecal IgG concentrations within 48 h. Increased IgG catabolism will result in serum IgG concentrations consistent with FPI (<1,000 mg/dL)6 at 48 h after transfusion. The objective of this study was to determine the rate of catabolism of colostral derived IgG administered by oroesophageal tubing compared to IV administered plasma IgG. Additionally, the half‐life of plasma and colostral derived IgG was determined.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

A randomized clinical trial was performed. The study was approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Sample size calculation was performed using methods for calculating sample size for 2 independent groups8 based on a standard deviation of 207 mg/dL for serum IgG concentrations in calves given plasma IV in previous studies4 (alpha = 0.05, power = 0.8, minimal detectable IgG concentration = 196 mg/dL). The required sample size was at least 7 calves in each group. To account for an anticipated dropout of up to 50% because of mortality, 30 calves (15 in each group) were enrolled. Thirty Jersey bull calves from a single farm in Hilmar, California were enrolled. Adult cows on the farm of study were vaccinated annually with a modified live respiratory disease vaccine containing infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, bovine viral diarrhea, parainfluenza‐3, and bovine respiratory syncytial viruses. Additionally, the cows were vaccinated with a multivalent vaccine containing Escherichia coli, rotavirus, and coronavirus during the dry cow period. Jersey bull calves delivered from eutocia and observed births were immediately separated from their dams before nursing colostrum. The calves were randomly assigned using a coin toss to 2 groups. Fifteen calves were assigned to the control group to receive colostrum (CL group) by oroesopheagal tubing, and 15 to the treatment group (PL group) to receive bovine plasma IV. The calves were weighed, identified using ear tags, transported within 36 h after enrollment and housed in individual calf hutches at the UC Davis Beef Research facilities.

Nonpooled bovine plasma was derived from 2 clinically healthy Holstein blood donor cows. The plasma was evaluated for sterility and considered free of transmissible blood‐borne pathogens. An aliquot (5 mL) of colostrum or plasma to be administered was collected before administration for IgG concentration determination. Plasma was administered through the jugular vein using an aseptically placed intravenous catheter1 at a dosage of 34 mL/kg. Infusion of plasma was performed at a rate of 10 mL/kg/h over the first 20 min. Monitoring for transfusion reactions included monitoring heart rate, respiratory rate, mucous membranes color, and abnormal behavior. In the absence of an immediate transfusion reaction, the remainder of the plasma was transfused over 20–30 min. In the event of a plasma transfusion reaction, transfusion was discontinued for 10 min and resumed at 5 mL/kg/h. Calves enrolled in the CL group received 3 L of pooled, pasteurized colostrum, from 1 batch collected from the farm of study, through an oroesophageal tube, once. Colostrum was pasteurized at 60°C for min using a batch pasteurizer. All calves received colostrum or bovine plasma within 2 h after birth. Thereafter, all calves were fed 2 L of nonmedicated milk replacer2 twice daily, 0.5 kg of nonmedicated commercial concentrate feed twice daily and water was available ad libitum. Calves were monitored 3 times daily. Daily calf monitoring procedures by trained personnel included assessment of rectal temperature, appetite for milk replacer, and concentrate feed and evidence of diarrhea or coughing. Decisions to medically treat calves were made by a UC Davis campus licensed veterinarian and not by the investigators. Calves that died during the study period were submitted for necropsy at the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory in Davis, CA.

Blood and fecal samples from each calf were collected by jugular venipuncture and digitally, respectively, at 0 h (before procedures), 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 5 d, and 7 d of age. Serum was harvested from the blood samples after centrifugation at 2,880 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Serum total protein concentration was determined by a hand‐held refractometer.3 Serum samples were then stored at −20°C until IgG determination. Fecal samples were immediately frozen at −20°C until IgG determination. Serum and fecal IgG determinations were performed by single radial immunodiffusion (SRID). All calves were enrolled within a 2‐wk period and the study was performed from June 2014 to July 2014.

Colostral, Plasma, and Serum IgG Determination

Colostral, plasma, and serum IgG concentrations were determined using a commercial SRID kit with a serum IgG determination range 196–2,748 mg/dL, based on the manufacturer's recommendations.4 Briefly, SRID plates containing specific anti‐bovine IgG, agarose gel, 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 0.1% sodium azide as a bacteriostatic agent and 1 μg/mL amphotericin B as an antifungal agent and stored in a refrigerator at 4°C were warmed at room temperature (20–24°C) for 30 min. Aliquots (5 μL) of the provided reference serum at 3 different concentrations (196, 1,402, and 2,748 mg/dL) were pipetted into individual SRID wells on every plate used. An aliquot (5 μL) of serum, plasma, or colostrum samples were pipetted into individual SRID plate wells. The plates were incubated at room temperature (20–24°C) for 24 h. The diameters of the zones of precipitation were measured using a digital SRID plate reader5 after 24 h. Serum, plasma, or colostral sample IgG concentrations were determined by comparing the diameter of the zones of precipitation with a standard curve generated by the reference serum. The regression equation generated in this manner (R 2 = 0.97–0.99) accurately predicted the inoculum IgG concentration. Minimum detectable serum IgG concentration was 196 mg/dL using the SRID. For the purposes of this study, calves determined to have serum IgG concentrations <196 mg/dL by SRID were assigned an IgG concentration of 195 mg/dL.

Fecal IgG Determination

Methods for fecal IgG extraction were adapted from a previous method performed on fecal samples from healthy dogs.9 Frozen fecal samples were thawed at room temperature until malleable. To decrease enzymatic degradation of the samples, only a few samples were evaluated each time. Once pliable, 1 g of feces was weighed into a 15 mL conical tube followed by addition 10 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 50 μL of protease inhibitor cocktail.6 The protease inhibitor was included to maintain the integrity of fecal IgG for later analysis. The mixture containing feces, PBS, and protease inhibitor then was homogenized using a vortex until the fecal clumps were dissolved. Samples then were centrifuged at 2,880 × g for 5 min at 4°C to separate larger fecal particles. Aliquots of the supernatant then were collected and 5 μL of each sample was pipetted immediately into individual RID wells. A commercial bovine ultra‐low‐level test kit with IgG concentration determination range18–100 mg/dL was used.7 The bovine ultra‐low‐level RID plates contained similar ingredients as the plates used for determination of plasma, serum, and colostral IgG concentrations. Aliquots (5 μL) of the provided reference serum at 3 different concentrations (10, 50 and 100 mg/dL) were pipetted into individual SRID wells on each plate used. The plates then were incubated at room temperature (20–24°C) for 24 h. The plates were read after 24 h. Fecal sample IgG concentrations were determined by comparing the diameter of the zones of precipitation with a standard curve generated by the reference serum. The regression equation generated in this manner (R 2 = 0.97–0.99) accurately predicted the inoculum fecal IgG concentration. For the purposes of this study, fecal samples with IgG concentrations <18 mg/dL were assigned an IgG concentration of 17 mg/dL. In instances where fecal IgG concentration was >100 mg/dL, SRID plates with a serum IgG determination range of 196–2,748 mg/dL were used.

Statistical Analysis

Normality of data were checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In instances where the data was not normally distributed, the median was reported. Descriptive statistics were calculated for calf birth weight, IgG concentrations in plasma administered, colostral IgG concentrations, serum total protein, and serum IgG concentrations at different time points, serum IgG concentrations at 48 h of age (to assess passive transfer status), morbidity and mortality events between the 2 groups. Apparent efficiency of absorption of IgG was determined as previously described.10 Serum IgG concentrations at 48 h between the 2 groups were compared using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Calves with serum IgG concentrations <1,000 mg/dL were considered to have FPI.6 Proportions of calves that died during the study period initially were compared between the 2 groups using a χ2 test or Fisher's exact test when a cell had <5 counts. A follow‐up conditional step‐wise logistic regression analysis was performed. The logistic regression predicted the probability of a mortality event in a calf as a function of group and medical treatment in sick calves. In the logistic regression, the final model fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow Goodness‐of‐Fit test.

In calves that received plasma transfusion, the predicted post‐transfusion serum IgG concentration was calculated using the following formula11:

where, calf weight is the mean weight (kg) of the calves in the PL group; 0.097 L plasma/kg is the plasma volume in Jersey calves10; plasma IgG is the calf serum IgG concentration (mg/dL) before administration of plasma; plasma IgG is the mean IgG concentration (mg/dL) in the plasma administered; plasma volume is the mean volume (L) of plasma administered IV.

To evaluate the decay of colostral or plasma derived IgG, serum half‐life for the 2 groups of calves was determined by a nonlinear regression analysis using a 1‐phase exponential decay model with random effects for calf initial serum IgG concentration.12 Differences in serum IgG half‐life between the 2 groups were evaluated by comparing the rate constants using an F‐test. The general predicted nonlinear regression model was represented as below:

where, Y is the response variable; Y 0 is the value of Y when X is equal zero; Plateau is the Y value at infinite times; K is the rate constant; X is the independent variable; e is the exponential function.

Tau was calculated as 1/K and half‐life (days) for IgG was calculated as ln(2)/K, where ln is the natural logarithm function.

Estimates of the probability of survival as a function of entry into study between the 2 groups were performed using survival analysis. Survival analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model.13 The proportional hazard assumption was evaluated using log‐minus‐log plots and the Schoenfield residuals.14 Entry into the study was considered to be 2 h of age after administration of plasma or colostrum. The specified outcome of interest was death. Survival curves were generated at 1 exit time point (7 d). At the exit time point calves that did not have the outcome of interest (death) were censored. The Wald‐chi square statistic was considered to determine whether group had an effect on survival of the calves at 7 d.13 The 2 survival distribution curves generated were compared to determine if they were different using the log‐rank test.13 All statistical analyses were performed using commercial statistical software.8 , 9 In all statistical analyses, values of P < .05 were considered significant.

Results

Colostral, Serum, and Fecal IgG Analysis

Mean calf weight ± SD for all calves was 29.8 ± 3.6 kg. Mean calf weight ± SD for the CL and PL groups was 30 ± 2.9 and 29.3 ± 4.2 kg respectively. There was no statistical difference in mean calf birth weight (P = .202) between the 2 groups. Mean IgG concentration for colostrum administered to the CL group was 6,780 ± 330 mg/dL. Thus, the mean dose of IgG fed to the CL group was 203,400 mg. Apparent efficiency of absorption for IgG was 24.8%. Thus, the mean IgG absorbed by the CL group was 50,444 mg. Mean ± SD IgG concentration for plasma administered to the PL group calves was 3172.9 ± 513.7 mg/dL. Thus, the predicted serum IgG concentration post‐transfusion in the PL group using a mean weight of 29.3 kg, pretransfusion IgG concentration of 195 mg/dL, mean plasma IgG concentration of 3172.9 mg/dL, and mean plasma administration volume of 997 mL (29.3 kg × 34 mL/kg) was 1,308 mg/dL. Mean total IgG transfused to the PL group was 31,634 mg. One calf experienced an immediate transfusion reaction. Median (range) of serum total protein and serum IgG concentrations at different time points are presented in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. Median serum IgG concentrations for both groups were >1,000 mg/dL at 6 h but only calves in the CL group maintained serum IgG >1,000 mg/dL after 6 h (Table 2). Calves in the CL group had higher serum IgG concentrations compared to the PL group (P < .0001) at 48 h. All calves in the CL group had adequate transfer of immunity whereas all calves in the PL group had FPI at 48 h of age.

Table 1.

Median (range) sTP concentrations at different time points in calves fed colostrum (CL) or administered bovine plasma IV (PL)

| Time | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| CL (g/dL) | PL (g/dL) | |

| 0 h | 4.0 (3.8–5.2) | 4.2 (3.8–5.6) |

| 6 h | 5.0 (4.6–6.0) | 5.0 (4.8–5.2) |

| 12 h | 5.5 (4.4–6.4) | 4.9 (4.6–5.2) |

| 24 h | 5.4 (5.0–6.7) | 5.3 (4.8–6.6) |

| 48 h | 5.8 (4.8–6.6) | 5.2 (4.3–7.0) |

| 5 d | 5.1 (5.0–6.6) | 4.4 (4.2–5.0) |

| 7 d | 5.0 (4.4–6.6) | 4.2 (3.8–4.6) |

Table 2.

Median (range) serum immunoglobulin G concentrations at different time points in calves fed colostrum (CL) or administered bovine plasma IV (PL)

| Time | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| CL (mg/dL) | PL (mg/dL) | |

| 0 h | 195 (195) | 195 (195) |

| 6 h | 1922.1 (1050.1–2505.8) | 1133.7 (603.3–1579.1) |

| 12 h | 2168.3 (1323.0–2914.9) | 905.6 (672.5–1336.0) |

| 24 h | 2193.8 (1272.2–3,339) | 706.9 (504.3–1336.6) |

| 48 h | 1729.4 (1127.6–2119.2)a | 650.3 (219.0–935.9)a |

| 5 d | 1415.0 (1127.6–2280.8) | 538.3 (246.9–753.8) |

| 7 d | 1490.6 (1020.1–2403.5) | 583.6 (167.5–800.4) |

Statistically different comparison (P < .05) at 48 h in determination of passive transfer status between the 2 groups.

Based on the general nonlinear regression model, the parameters for the models generated for the CL and PL groups are presented in Table 3. The nonlinear models for the 2 groups are represented below:

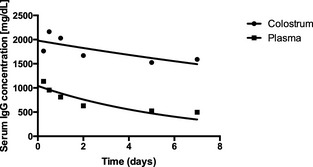

where e is the exponential function, Y is serum IgG concentration, and X represents time. The serum IgG half‐life for the CL group (17.1 d) was significantly longer than that of the PL group (4.4 d; P < .0001). The decay curves for IgG for the 2 groups are presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Predicted immunoglobulin G (IgG) decay models for calves fed colostrum (CL) or administered bovine plasma IV (PL)

| Estimates (95% confidence interval) | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| CL | PL | |

| Y 0 (mg/dL) | 1,980 (1,822–2,137) | 1,042 (940.9–1,143) |

| Plateau | 0 | 0 |

| K (d) | 0.040 (0.014–0.067) | 0.158 (0.096–0.219) |

| Tau | 24.73 (15.0–70.36) | 6.35 (4.57–10.39) |

| Half‐life (d) | 17.1 (10.4–48.8) | 4.4 (3.2–7.2) |

| R 2 | 0.11 | 0.36 |

The plateau was constrained to zero after subtracting the precolostral or pretransfusion serum IgG concentrations.

Figure 1.

Serum IgG decay curves for calves fed colostrum (CL group, n = 15) or IV bovine plasma administration (PL group, n = 15).

Median (range) fecal IgG concentrations are presented in Table 4. Median fecal IgG concentrations were higher in the CL group compared to the PL group at 5 d (P < .0001). Median fecal IgG concentrations were not statistically different between the 2 groups at 6 h (P = 1), 12 h (P = 1), 24 h (P = 1), 48 h (P = .070), and 7 d (P = .205).

Table 4.

Median (range) fecal immunoglobulin G concentrations at different time points in calves fed colostrum (CL) or administered bovine plasma IV (PL)

| Time | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| CL (mg/dL) | PL (mg/dL) | |

| 0 h | 17 (17) | 17 (17) |

| 6 h | 17 (17) | 17 (17) |

| 12 h | 17 (17) | 17 (17) |

| 24 h | 17 (17) | 17 (17) |

| 48 h | 54.6 (9–83.8) | 22.2 (9–94.3) |

| 5 d | 68.3 (36.4–99.5)a | 22.0 (9–29.5)a |

| 7 d | 14.1 (9–67.6) | 10 (9–37.2) |

Statistically different comparison (P < .05).

Morbidity and Mortality

Six calves (40%) in the CL group and 13 (87.7%) in the PL group experienced a morbidity event during the study period. The morbidity event in all calves was diarrhea. All morbidity events required medical treatment with PO rehydration electrolytes and antimicrobials. Two calves in the CL group (13.3%) and 8 (53.3%) in PL group died during the study period. The proportion of mortality between the 2 groups was statistically different (P = .025). The causes of mortality in the calves were diarrhea with secondary septicemia caused by enterotoxigenic E. coli (2 calves) Proteus spp. (2 calves) and Salmonella Montevideo (6 calves). The logistic regression parameters are presented in Table 5. The probability of mortality in the calves as a function of group (CL or PL) and medical treatment of sick calves was calculated by use of the following equation:

where e is the exponential function.

Table 5.

Logistic model predicting probability of a calf experiencing mortality in 30 calves

| Variable | Coefficient (95% confidence interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.195 (−0.0009 to 0.391) | .051 |

| Group | 0.585 (0.286 to 0.884) | .0001 |

| Treatment | −0.463 (−0.781 to −0.146) | .0042 |

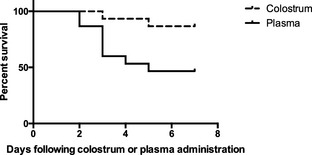

Kaplan–Meier curves for the CL and PL groups are depicted in Figure 2. Median survival time for the PL group calves was 5 d. Median survival for the CL group was undefined because <50% of the calves had experienced mortality at the time of study completion. The survival rates between the CL and the PL group were statistically different (P = .017) during the study period. Calves in the PL group were 5.0 times more likely to experience mortality during the study period (hazard ratio, 5.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.43, 17.29).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the colostrum group (CL; n = 15) and plasma group (PL; n = 15) groups depicting percentage survival of calves after the start of the study.

Discussion

The major finding in this study was the rapid decrease in serum IgG concentrations to those consistent with FPI in the PL group calves within the first 12 h after transfusion. Although the median serum IgG concentration reached concentrations consistent with adequate transfer of immunity (serum IgG concentrations ≥1,000 mg/dL) at 6 h after plasma transfusion, the concentrations were not maintained beyond 6 h. The half‐life of plasma derived IgG was only 4.4 d compared to 17.1 d for colostral derived IgG. The median IgG concentrations indicative of FPI after 6 h and the short half‐life of plasma derived IgG in the PL group indicated that the rate of catabolism of plasma derived IgG was higher compared to colostral derived IgG. Calves in the CL group maintained serum IgG concentrations consistent with adequate transfer of immunity during the 7‐d study period. Fecal IgG concentrations were not different between the 2 groups except at 5 d of age when the CL group had higher fecal concentrations. Thus, fecal IgG concentration did not explain the fate of the rapidly decreasing serum IgG in the PL group. There are 2 possible explanations for the insignificant differences in the fecal IgG concentrations between the 2 groups before 5 d of age. First, results of studies in human patients with active or benign inflammatory bowel diseases15 and clinical healthy dogs9 suggested that fecal immunoglobulin determinations tests were less reliable because of lower detection rates (<0.01 to 35.5%). In the study in humans with active or benign inflammatory bowel disease, complete intestinal lavage was recommended for detection of fecal IgG.15 Secondly, detection of IgG by SRID is based on the binding of the IgG molecule to the anti‐bovine IgG in the agarose gel.16 Consequently, destruction of the IgG binding site during preparation of fecal samples for IgG determination will result in lower detection rates of fecal IgG. The physiological mechanism resulting in increased catabolism of plasma derived IgG may be similar to the mechanism suggested studies of humans.7 The studies7 indicated that IgG aggregates formed during plasma preparation might activate complement after transfusion resulting in increased catabolism of IgG.

The results of this study have some clinical applications. In clinical settings, the high cost of bovine plasma may be prohibitive. Consequently, a lower bovine plasma dosage may be preferred in calves given plasma. Thus, it is important to consider the higher dosage rates (30–40 mL/kg) to successfully increase serum IgG concentration to those consistent with adequate transfer of immunity. Furthermore, the rapid decrease in serum IgG concentration after plasma transfusion may warrant repeated transfusion within 12 h when necessary to maintain serum IgG concentrations consistent with adequate transfer of immunity. However, repeated plasma transfusions may predispose to transfusion reactions. Serum total protein concentration was an inconsistent test in classifying calves with FPI after transfusion. This is because median serum total protein concentrations ≥5.2 g/dL at 48 h of age achieved by the PL group calves are considered indicative of adequate transfer of immunity.1 In contrast, all calves in the PL group had serum IgG concentrations consistent with FPI based on the reference method (SRID).

The half‐life of 17.1 d for colostral IgG reported in this study is consistent with a previous study17 that reported a half‐life of 17.9 d. However, the colostral derived IgG half‐life also is shorter in comparison to other studies.4 Additionally, the half‐life for plasma derived IgG reported in this study was substantially shorter than the 27.3 d reported in previous studies.4 Two possible reasons might account for the differences in the results. First, serum IgG determination was only performed 48 h after colostrum or plasma administration in the other studies.4 Considering that a significant decrease in serum IgG concentration occurred during the first 12 h after plasma transfusion and a significant increase in serum IgG concentrations occurred before 48 h in the CL group (Table 2) in this study, the estimation of IgG half‐life potentially was affected by the study design. The second potential explanation for the differences in the half‐life of colostral or plasma derived IgG between the studies was the duration of the follow‐up period. The study period reported here was 7 d compared to 35 d in a previous study.4 We chose to collect samples only up to 7 d because antibodies to different bacterial, protozoal, and viral antigens do not appear in blood before 14–30 d of age.18, 19 Thus, we chose a time period before the expected appearance of endogenously synthesized immunoglobulins to minimize effects on serum IgG half‐life determination. Mortality rates in the PL group were significantly high compared to the CL group consistent with previous studies4 indicating that plasma is unlikely to provide protective immunity comparable to maternal colostrum. Based on survival analysis, calves in the PL group were 5 times (hazard ratio, 5.01) more likely to experience mortality compared to those in the CL group. Based on logistic regression analysis, PL group calves that received treatments were 1.4 times more likely to experience mortality (relative risk, 1.4) compared to the PL group calves that received treatment.

There are several limitations of this study. In clinical practice, calves that experience FPI and are transfused with bovine plasma are likely to have been fed insufficient colostrum rather than no colostrum. The PL group calves in this study were colostrum deprived. In addition to immunoglobulins, colostrum contains maternally derived immunoreactive cells, which stimulate the calf's immune system.20 Thus, the effects of administration of plasma on serum IgG concentrations and immunoreactive cells in calves that experience FPI caused by insufficient colostrum ingestion warrant further investigation. Furthermore, the majority of calves for which plasma administration is recommended are more likely to be clinically sick. In contrast, calves were considered clinically healthy at the time of plasma administration in this study. Studies evaluating effect of plasma administration on serum IgG concentration in sick neonatal calves are recommended.

Conclusions

Plasma derived IgG concentrations rapidly decrease within 12 h after transfusion in calves. Fecal excretion did not explain the fate of the rapidly decreasing plasma derived IgG. As a result of increased catabolism and short half‐life of plasma‐derived IgG, plasma dosage ranging from 30 to 40 mL/kg are recommended with repeated transfusions within 12 h, if necessary.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by the UC Davis Student Training in Advanced Research Grants and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Formula Funds).

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

Footnotes

14 G × 3.25 Angiocath; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ

Calva‐Lac; Calva Products, Acampo, CA

Master Refractometer, Atago, Bellevue, WA

Bovine IgG test kit, 200–3,000 mg/dL; Triple‐J Farms, Bellingham, WA

Digital RID Plate Reader; The Binding Site, San Diego, CA

Protease Cocktail Set III, Millipore, Billerica, MA

Bovine IgG test kit, 18–100 mg/dL; Triple‐J Farms, Bellingham, WA

Prism 6, GraphPad Inc, La Jolla, CA

SAS Version 9.4; Cary, NC

References

- 1. Tyler JW, Hancock DD, Thorne J, et al. Partitioning the mortality risk associated with inadequate passive transfer of colostral immunoglobulins in dairy calves. J Vet Intern Med 1999;13:335–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Virtala AM, Gröhn YT, Mechor GD, Erb HN. The effect of maternally derived immunoglobulin G on the risk of respiratory disease in heifers during the first 3 months of life. Prev Vet Med 1999;39:25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas KW, Pemberton DH. A freeze‐thaw method for concentrating plasma and serum for treatment of hypogammaglobinaemia. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci 1980;58:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murphy JM, Hagey JV, Chigerwe M. Comparison of serum immunoglobulin G half‐life in dairy calves fed colostrum, colostrum replacer or administered with intravenous bovine plasma. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2014;158:233–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chigerwe M, Barrington GM. Ruminant immunodeficiency diseases In: Smith BP, ed. Large Animal Internal Medicine, 5th ed St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015:1572–1575. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Besser TE, Gay CC, Pritchett L. Comparison of three methods of feeding colostrum to dairy calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;198:419–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lundblad JL, Londeree N. The effect of processing methods on intravenous immune globulin preparations. J Hosp Infect 1988;12:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Toft N, Houe H, Nielsen SS. Sample size and sampling methods In: Hans H, Ersbol AK, Toft N, eds. Introduction to Veterinary Epidemiology, 1st ed Frederiksberg: Denmark; Biofilia; 2004:109–131. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peters IR, Calvert EL, Hall EJ, et al. Measurement of immunoglobulin concentrations in the feces of healthy dogs. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2004;11:841–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quigley JD, Drewry JJ, Martin KR. Estimation of plasma volume in Holstein and Jersey calves. J Dairy Sci 1988;81:1308–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chigerwe M, Tyler JW. Serum IgG concentration after intravenous serum transfusion in a randomized clinical trial in dairy calves with inadequate transfer of colostral immunoglobulins. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zar JB. Multiple regression and correlation In: Biostatistical Analysis, 4th ed Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice‐Hall Inc; 1999:413–443. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. The Cox proportional hazards model and its characteristics In: Gail M, Krickeberg J, Samet J, Tsiatis A, Wong W, eds. Statistical for Biology and Health. Survival Analysis, 2nd ed New York, NY; Springer; 2005:83–129. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferguson A, Humphreys KA, Croft NM. Technical report: results of immunological tests on fecal extracts are likely to be extremely misleading. Clin Exp Immunol 1995;99:70–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fahey JL, McKelvey EM. Quantitative determination of serum immunoglobulins in antibody agar plates. J Immunol 1965;94:84–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Besser TE, McGuire TC, Gay CC, et al. Transfer of functional immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody into the gastrointestinal tract accounts for IgG clearance in calves. J Virol 1988;64:2234–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith AN, Ingram DG. Immunological responses of young animals. II. Antibody production in calves. Can Vet J 1965;6:226–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kerr WR. Active immunity experiments in very young calves. Vet Rec 1956;68:476–477. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reber AJ, Donovan DC, Gabbard J, et al. Transfer of maternal colostral leukocytes promotes development of the neonatal immune system Part II. Effects on neonatal lymphocytes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2008;123:305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]