Abstract

Equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs) facilitate the flux of nucleosides, such as adenosine, and nucleoside analog (NA) drugs across cell membranes. A correlation between adenosine flux and calcium-dependent signaling has been previously reported; however, the mechanistic basis of these observations is not known. Here we report the identification of the calcium signaling transducer calmodulin (CaM) as an ENT1-interacting protein, via a conserved classic 1-5-10 motif in ENT1. Calcium-dependent human ENT1-CaM protein interactions were confirmed in human cell lines (HEK293, RT4, U-87 MG) using biochemical assays (HEK293) and the functional assays (HEK293, RT4), which confirmed modified nucleoside uptake that occurred in the presence of pharmacological manipulations of calcium levels and CaM function. Nucleoside and NA drug uptake was significantly decreased (∼12% and ∼39%, respectively) by chelating calcium (EGTA, 50 μM; BAPTA-AM, 25 μM), whereas increasing intracellular calcium (thapsigargin, 1.5 μM) led to increased nucleoside uptake (∼26%). Activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (in U-87 MG) by glutamate (1 mM) and glycine (100 μM) significantly increased nucleoside uptake (∼38%) except in the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801 (50 μM), or CaM antagonist, W7 (50 μM). These data support the existence of a previously unidentified novel receptor-dependent regulatory mechanism, whereby intracellular calcium modulates nucleoside and NA drug uptake via CaM-dependent interaction of ENT1. These findings suggest that ENT1 is regulated via receptor-dependent calcium-linked pathways resulting in an alteration of purine flux, which may modulate purinergic signaling and influence NA drug efficacy.

Keywords: equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1, interactome, calcium, calmodulin, regulation

equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1), the prototypic member of the SLC29 family of transporters, is an integral membrane protein responsible for transporting nucleosides and nucleoside analog drugs across cellular membranes (34, 66). There are four members of the SLC29 family and two isoforms, ENT1 and ENT2. These proteins are clinically significant and are essential for the efficacy of many cytotoxic nucleoside analog drugs used to treat cancer and viral and parasitic infections (29). ENT1 is also a key player in the purinome, where it modulates adenosine flux in many tissues affecting a number of purinergic signaling pathways (23, 52).

Although there is an increasing understanding of the structural and functional aspects of ENT family members (6, 62) and their role and relevance to clinical outcomes (18, 27), our understanding of the mechanisms of regulation of ENTs is still limited. Previous work has identified a number of potential regulatory mechanisms such as protein phosphorylation (4, 11, 49), possibly as a consequence of receptor activation (30), and these mechanisms have been implicated in functional aspects of ENT-dependent nucleoside uptake (4, 45, 54) although a direct relationship between phosphorylation and function remains to be demonstrated. In addition, a number of studies in both mammalian and nonmammalian systems have demonstrated a role for calcium-modulating ENT-dependent nucleoside flux (40, 63, 67), suggesting that calcium regulation may be a ubiquitous form of regulation for these transporters although underlying mechanisms and proteins involved in the regulation have not been described. Despite the lack of information on mechanisms of regulation, it is increasingly evident that ENT1 and ENT2 play central roles in a variety of physiologically and clinically relevant settings (16, 23, 51, 52, 68), and we hypothesize they are participating in complex regulatory networks and pathways. Understanding the regulation of other transporters has been assisted by identification of interacting proteins (20, 33, 36, 55). Therefore, identification and characterization of the ENT1 interactome will provide insight into the nature and the underlying mechanisms of regulation of ENT1 by protein-protein interactions.

Previous work has shown a correlation between changes in calcium flux and altered nucleoside uptake (40, 67, 63), but the nature of this relationship and underlying mechanisms are unknown. Many studies now suggest that ENT1 is likely to participate in, or be responsive to, a number of complex regulatory networks and pathways. In this study, we use a proteomic approach to characterize the interactome and identified calmodulin (CaM) as a novel calcium-dependent interacting protein partner of ENT1. Furthermore, we confirmed that a functionally relevant, calcium-dependent interaction exists between ENT1 and CaM in human cell lines and defined a mechanistically novel mode of regulation of ENT1. These data explain previous observations linking receptor-dependent calcium pathways to purinergic signaling (40, 63, 67). These data also suggest that nucleoside analog drug uptake may be affected by variations in calcium signaling depending on the context, suggesting both opportunities for enhancement of nucleoside analog drug efficacy as well contraindications with calcium-influencing drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

[3H]-2-chloroadenosine and [3H]-gemcitabine were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA), BAPTA-AM from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA), cOmplete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche (Basel, Switzerland), and CALP2, gemcitabine hydrochloride, and W7 hydrochloride from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Bait construction for MYTH.

Despite repeated attempts, we were unable to successfully clone hENT1 in the membrane yeast two-hybrid (MYTH) vector and therefore used mENT1 for the MYTH screen. Cloning of mENT1 into a MYTH vector, pTLB-1 (Dualsystems Biotech, Schlieren, Switzerland) allows for the bait protein to be fused to the NH2-terminal region of the Cub transcription factors. To achieve this, mENT1 cDNA was amplified from its host plasmid by standard PCR using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolaboratories, Ipswich, MA). The mENT1 cDNA was then ligated into both MYTH vectors via homologous recombination via a standard yeast transformation. The yeast strain THY.AP4 [MATa leu2, ura3, trp1 :: (lexAop-lacZ) (lexAop)-HIS3 (lexAop)-ADE2] was employed. To check for self-activation of the MYTH vectors with mENT1 cDNA, NubG/NubI tests were performed, whereby yeast carrying the mENT1 MYTH vector was transformed with control plasmids Fur4, NubI, Ost1 NubI (positive control), Ost1, NubG, and Fur4 NubG (negative control) by standard yeast transformation. Following growth on SD-WL plates, a range of serial dilutions from 1:100–1:10,000 was performed, and samples were spotted onto SD-WLAH plates with varying amounts of 3-amino-1,2,4 triazole (3-AT), up to 100 mM, and allowed to incubate at 30°C for 2–5 days.

MYTH assay.

MYTH assays were performed as previously described (20, 36, 55, 56, 59). The yeast strain THY.AP4 [MATa leu2, ura3, trp1 :: (lexAop-lacZ) (lexAop)- HIS3 (lexAop)-ADE2] was transformed with the mENT1 pTLB-1 bait plasmid and the 11-day whole-mouse embryo NubG-X prey plasmid using the lithium acetate method (22) and plated on SD-WL plates. Colonies were selected based on size and shape, diluted in 100 μl of ddH2O, and spotted onto SD-WL and SD-WLAH ± 3-AT X-Gal plates. Colonies that grew and exhibited β-galactosidase activity were scored as positive for an interaction between the bait and prey.

Positive prey plasmids that were selected from the positive colonies obtained from the MYTH screens were retransformed into THY.AP4 yeast with mENT1 pTLB-1 bait plasmid, as well as control bait plasmid that consisted of an artificial bait protein, which will not interact with any protein. The transformants were plated serially in triplicates on SD-WL and SD-WLAH X-GAL plates with 100 mM 3-AT. Colonies that showed β-galactosidase activity in both the mENT1 and artificial bait transformants were determined to be self-activating and discarded. Those that did not show self-activation were selected for further screening.

Bioinformatic prey analysis.

CaM was identified as a putative protein partner of ENT1. The human (GI:1845344) and mouse ENT1 (AF131212) protein sequences were analyzed and compared with known CaM interactors in the Calmodulin Target Database (65).

Cell culture.

RT4 (HTB-2) cells, a human bladder epithelial cancer cell line, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were grown in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 10% FBS. For [3H]-gemcitabine uptake assays, cells were left to attach for 24 h.

HEK293 cells, a transformed human embryonic kidney cell line, were grown in standard DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS.

U-87 MG (HTB-14) cells, a human brain glioblastoma epithelial cancer cell line, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. The cells were grown in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

RT4, HEK293, and U-87 MG cell lines were incubated in 5% (vol/vol) CO2 and 95% (vol/vol) air at 37°C. Cells were plated in six-well plates for uptake assays, 10-cm plates for nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBTI)-binding analysis, and 60-mm plates for Western blotting analysis. Cells for live cell imaging were seeded on no. 1.5 glass-bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA).

Rationale for cell line choice.

HEK293 cells were chosen for biochemical and functional assays because they have well-known nucleoside transporter characteristics, are comparatively low maintenance, exhibit rapid growth, and are reliably adherent during transport assays.

To confirm our proposed mechanism of Ca2+/CaM-regulating nucleoside flux, we used U-87 MG cells, an immortalized Homo sapiens astrocytoma cell line, which express mRNA for NR2A and NR2B subunits, show presence of NR2B protein, and for which electrophysiological data suggest Ca2+ influx results from ligand- or voltage-gated calcium channels (14, 32, 60). Recent studies on the role of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor signaling have identified physiologically relevant NMDA receptors in glial cells linked to physiologically relevant roles (15, 41, 42). Although U-87 MG cells are not a classic model for NMDA receptor signaling studies, they possess glutamate/glycine-activated NMDA receptor-dependent regulation of metalloproteinase activity and proliferation (46). These cells are also reliably adherent and thus suitable for functional transport assays. We confirmed the presence of the NR1 subunit by Western blotting analysis, verified that the NMDA receptors were functional by performing Fluo-4 live cell calcium imaging to confirm that glutamate and glycine treatment led to an increase in calcium transients (blocked in presence of the tight binding, noncompetitive NMDAR antagonist MK-801), and used MK-801 treatment in our 2-chloroadenosine transport assays to corroborate previous observations (40) that NMDAR activation led to a sodium-independent nucleoside flux.

Construct design for HA-ENT1.

An HA tag was cloned into the hENT1 coding sequence after the amino acid at position 64 (HA tag underlined). The HA tag is located at the beginning of the first, large extracellular loop. The sequence was submitted to DNA 2.0 (Menlo Park, CA) for generation of a mammalian expression vector to express HA-hENT1:

1 MTTSHQPQDR YKAVWLIFFM LGLGTLLPWN FFMTATQYFT NRLDMSQNVS LVTAELSKDA;

61 QASAYPYDVP DYAAPAAPLP ERNSLSAIFN NVMTLCAMLP LLLFTYLNSF LHQRIPQSVR;

121 ILGSLVAILL VFLITAILVK VQLDALPFFV ITMIKIVLIN SFGAILQGSL FGLAGLLPAS;

181 YTAPIMSGQG LAGFFASVAM ICAIASGSEL SESAFGYFIT ACAVIILTII CYLGLPRLEF;

241 YRYYQQLKLE GPGEQETKLD LISKGEEPRA GKEESGVSVS NSQPTNESHS IKAILKNISV;

301 LAFSVCFIFT ITIGMFPAVT VEVKSSIAGS STWERYFIPV SCFLTFNIFD WLGRSLTAVF;

361 MWPGKDSRWL PSLVLARLVF VPLLLLCNIK PRRYLTVVFE HDAWFIFFMA AFAFSNGYLA;

421 SLCMCFGPKK VKPAEAETAG AIMAFFLCLG LALGAVFSFL FRAIV.

Coimmunoprecipitation of CaM using HA-hENT1 bait.

HEK293 cells transfected with HA-ENT1 and after ∼36 h were lysed with NP-40 buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (vol/vol) NP-40, 1 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, and protease inhibitor cocktail] by homogenizing with a 1-ml syringe and 26-gauge needle and then centrifuged at 8,000 revolution/min for 25 min in a bench-top centrifuge to pellet cellular debris and organelle. Protein concentration was determined using a modified Lowry protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and 600 μg of protein lysate was loaded to a column with 20 μl of anti-HA beads (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The protein was agitated using a rotator for 2 h at room temperature (∼23°C) and was then washed six times with Tween-20 Tris-buffered saline (TTBS) containing 2 mM CaCl2 or without calcium in the presence and absence of EGTA. The immunoprecipitated protein was recovered by adding protein loading buffer, boiled at 95°C for 10 min (Thermo Scientific), and was supplemented with 2 μl of 1 M DDT. Elution and flow-through protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting against CaM [primary antibody, 1716-1, 1:1,000 dilution; Epitomics, Cambridge, MA; secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit 1:4,000]. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ.

Protein expression for NMR analysis and fluorescence anisotropy.

A chimeric gene encoding the large intracellular loop (residues 228–290) of hENT1, in tandem with a 6xHis-ubiquitin tag and an intervening thrombin site, was designed and commercially synthesized in the expression vector, pJexpress 401 by DNA 2.0. A human CaM clone was kindly provided by Dr. Mitsu Ikura (University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and consisted of CaM cloned into a pET15b with 6xHis tagged and an interpolated thrombin site at the NH2-terminal. CaM fusion peptides were expressed in a conventional M9 minimal media (in 1-l batches) with 15N-ammonium chloride as the only source of nitrogen, whereas conventional LB media was used to generate peptides for fluorescence anisotropy. The 6xHis-ubiquitin-hENT1 loop proteins were expressed in LB-Kan in a culture of Escherichia coli BL21:DE3 cells. The cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.8 and then induced with isopropylthiogalactoside for 3 h. Cells were then centrifuged (10,000 g for 10 min) and lysed with a French press. The fusion peptides were purified from the cell lysate by a combination of standard nickel affinity and gel filtration chromatography.

NMR measurements.

Uniformly 15N-labeled CaM at 0.12 mM in PBS, supplemented with 10% D2O and 3 μM of CaCl2, was titrated with 6xHis-ubiquitin-hENT1 at a 1:2 ratio in a 15N-edited heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra (768 × 80 pts) acquired on a 600-MHz Varian NMR spectrometer (31). HSQC spectra can provide evidence for protein-protein interactions if there are shifts in peaks when comparing the spectra of the free protein with the spectra of two interacting proteins.

Fluorescence anisotropy.

Fluorescence anisotropy is a technique that analyzes the ratio of polarized light to total light emitted from a fluorophore and enables the measurement of binding constants between a fluorophore-tagged molecule and an untagged molecule (6). A complex of a fluorescently tagged peptide with a binding partner will rotate more slowly than unbound peptide. Fluorescence anisotropy can therefore be used to determine the dissociation constant (Kd) of interacting proteins and has previously been used to measure the affinity between CaM and other membrane proteins (17, 26).

Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were made with a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer at room temperature. Titrations were performed in Hepes buffer (25 mM Hepes, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) with hENT1 peptide concentrations of 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 75, and 95 μM. The hENT1 intracellular loop peptides were fluorescently tagged and consisted of the putative 1-5-10 CaM-binding site in the large intracellular loop of hENT1 (residues 224–245) with three COOH-terminal lysines added to enhance solubility, a PEG spacer, and an NH2-terminal fluorescein derivative tag (CanPeptide, Pointe-Claire, Québec, Canada) as follows: wild-type: LGLPRLEFYRYYQQLKLEGPGKKK; ΔCaM-5:LGLPRLERRRHRQQLKREGPGKKK; ΔCaM-3: LGLPRLERYRYRQQLKREGPGKKK.

The peptides were kept at a constant concentration of 2 μM during the titrations. Fluorescence anisotropy was measured at an excitation wavelength of 494.0 nm and an emission wavelength of 523.0 nm. Anisotropy, R, is measured using the equation: R = (Ivv − G * Ivh)/(Ivv + 2 * G * Ivh), where Ivv represents both polarizers in the vertical position, Ivh represents the perpendicular polarizer in the horizontal position, and G is the G factor. Average relative anisotropy was calculated, after at least three experiments per peptide, by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism version 5.04 for Windows.

[3H] uptake assays.

[3H]-2-chloroadenosine and [3H]-gemcitabine uptakes were measured as previously described (11). Cells were incubated for 10 s in sodium-free transport buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20 mM Tris·HCl, 3 mM K2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glucose, 130 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine, and permeant (10 μM 2-chloroadenosine or gemcitabine) and radiolabeled nucleosides at room temperature because uptake kinetics are the same as with 37°C transport assays (3). The uptake was stopped by rapid aspiration of permeant solution and immediate washing of cells three times with ice-cold sodium-free transport buffer containing 100 nM NBTI and 30 μM dipyridamole. Cells were lysed in 2 M NaOH for 48 h at 4°C. Aliquots were taken to measure protein content (modified Lowry protein assay, Bio-Rad) and nucleoside uptake (standard liquid scintillation counting). Nucleoside uptake was expressed as picomoles per milligram of protein per unit time.

Calcium levels were manipulated by replacing media with calcium-free buffer or by treating cells with media containing BAPTA-AM (25 μM), EGTA (50 μM), or thapsigargin (1.5 μM) for 1 min before the beginning of the uptake assay. Treatment with the CaM antagonist W7 (50 μM) was for 1 min in media. Cells were FBS-starved for 20 h before treatment.

For glutamate (1 mM) and glycine (100 μM) treatment, cells were washed twice with 37°C preheated HBSS (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 20 mM Hepes, 4 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2) and incubated for 10 min in HBSS at 37°C, and then cells were incubated for 20 min after the addition of 1 mM glutamate and 100 μM glycine at 37°C.

Live cell calcium imaging with Fluo-4.

Glass-bottom dishes of HEK293 cells or U-87 MG cells had media replaced with fresh DMEM +10% FBS or EMEM + 10% FBS, respectively. Cells were incubated with 4 μM Fluo-4 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and 0.02% (wt/vol) Pluronic F-127 at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 45 min.

After incubation, HEK293 cells were washed twice with prewarmed 1× PBS and were imaged in media + 10% FBS. HEK293 cells following 1.5 μM thapsigargin treatment were imaged using Zeiss AxioObserver spinning disc confocal microscope to capture a single plane every 5 s using a ×40 oil immersion objective (N.A. = 1.40), exciting with the 488-nm laser. Basal fluorescence intensity was established by imaging HEK293 cells in media for 5 min, and then, upon addition of thapsigargin (t = 0), cells were imaged for 10 min.

Calcium signaling of U-87 MG cells was assessed by quantifying calcium signaling events and was measured using the Zeiss LSM 700 inverted confocal microscope with image acquisition of one focal plane every 5 s using a ×10 objective (N.A. = 0.45) following the imaging protocol previously described (64). Following incubation with Fluo-4 for 45 min, cells were washed twice, preincubated with HBSS for 20 min, and were then imaged for 10 min in HBSS to establish the basal rate of calcium transients. This was determined by counting the number of cells experiencing a rapid, large, transient increase in fluorescence intensity over time in the set field of view (64). To determine the change in calcium signaling events, cells were imaged for 10 min following treatment with either 1 mM glutamate and 100 μM glycine, or 100 μM glycine. After 10 min of image acquisition, MK-801 was added to the plate (50 μM), and images were recorded for 10 min. Data analysis was performed using Zen Blue 2013 software for Windows, and histogram was generated using GraphPad Prism 5.04 for Windows.

Western blotting analysis.

U-87 MG cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors cocktail) through freezing (liquid nitrogen) and thawing (42°C water bath) in a total of four cycles followed by three cycles of sonication. Lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 revolution/min for 25 min at 4°C to pellet cellular debris and organelle. The supernatant was then centrifuged for 1.5 h at 55,000 revolution/min at 4°C. The crude membranes pellet was resuspended in membrane solubilizing buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.5% SDS). The protein concentration was determined using a modified Lowry protein assay (Bio-Rad). Positive control (crude synaptoneurosome preparation of mouse brain tissue) protein was provided by the Ramsey laboratory and was prepared by following the protocol from Li et al. (2010). U-87 MG crude membrane protein (100 μg) and positive control protein (0.5 μg) were each mixed with protein loading buffer, incubated for 10 min at 55°C, and analyzed following SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) were blocked for 45 min in 5% milk and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-ENT1 antibody (ab48607; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and mouse monoclonal anti-NMDA receptor 1 antibody (mab1586; EMD Millipore) in 1% (vol/vol) milk overnight at 4°C using the manufacturer's recommended dilutions. After being washed with TTBS, the nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies in 1% (vol/vol) milk for 1.5 h at room temperature, followed with two washes of TTBS and one wash with TBS, each for 10 min. Enhanced chemiluminescence was added, the membrane was exposed to film, and then the film was developed.

RESULTS

Identifying the role of calcium in regulating sodium-independent nucleoside and nucleoside analog drug uptake.

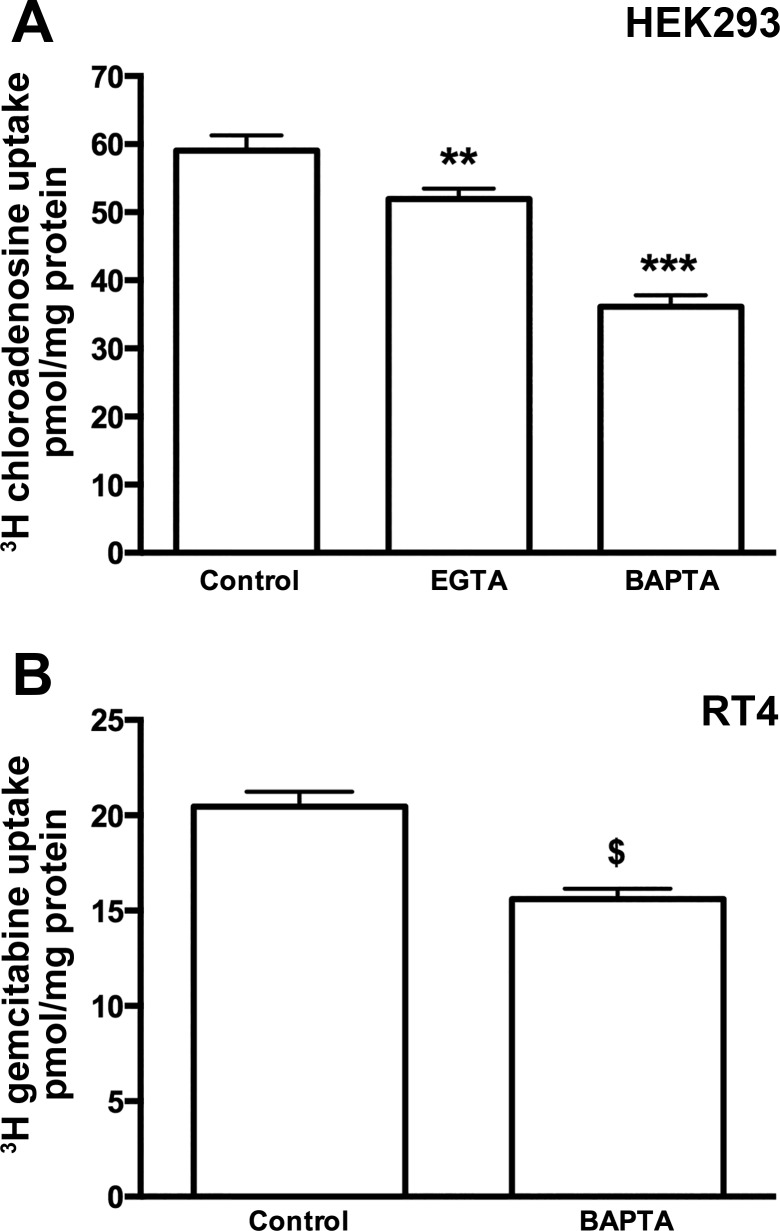

Previous work has shown a correlation between calcium levels and adenosine flux in neural cells (67, 63). To confirm that calcium regulates ENT-dependent nucleoside and nucleoside analog drug transport in other cell types, we measured chloroadenosine uptake in HEK293 cells and gemcitabine uptake in RT4 cells in the presence of intracellular (BAPTA-AM) and extracellular (EGTA) chelators of calcium. Our data show that chelating either extracellular and/or intracellular calcium results in significantly reduced (∼12% for EGTA and ∼39% for BAPTA-AM) nucleoside transport in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1A) and that chelation of intracellular calcium decreases gemcitabine transport (∼24%) in RT4 cells (Fig. 1B), confirming a relationship between calcium levels and nucleoside transport in these cells.

Fig. 1.

Reduced calcium levels lead to reduced nucleoside transport. A: HEK293 cells were treated (1 min) in Ca2+-containing, Ca2+-free buffer + 50 μM EGTA, or Ca2+-free buffer + 25 μM BAPTA-AM. EGTA and BAPTA-AM treatments significantly reduced [3H]-chloroadenosine uptake. Pooled data from 3 individual experiments, with each condition conducted in sextuplicate, are presented as means ± SE (1-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison post hoc test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 3). B: RT4 cells maintained briefly (1 min) in calcium-free condition with the addition of 25 μM BAPTA-AM had significantly reduced [3H]-gemcitabine uptake compared with control. Pooled data from 3 individual experiments (n = 3), with each condition conducted in sextuplicate, are presented as means ± SE (t-test, $P < 0.0001).

Identifying ENT1-binding protein candidates.

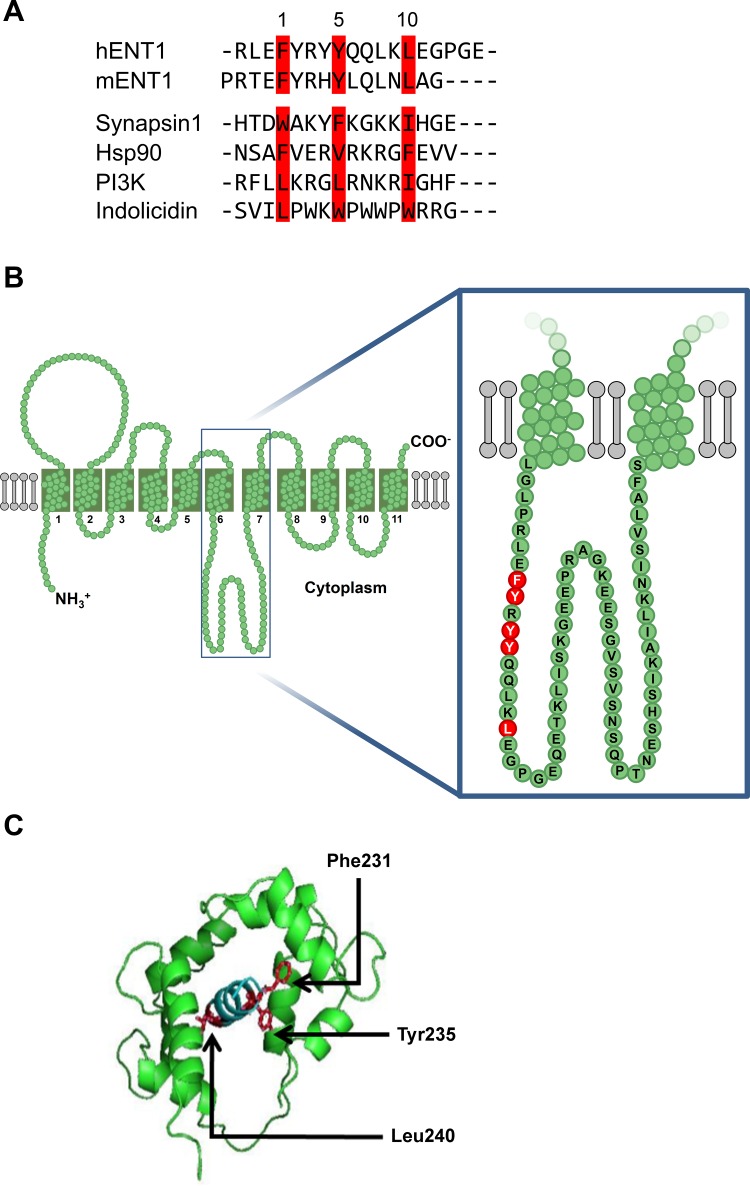

Given previous observations that calcium signaling regulates adenosine flux in some cell types (40, 67), we suspected that CaM could be the underlying mechanism of action through direct interaction with ENT1. We conducted an in silico analysis of the hENT1 sequence using the Calmodulin Target Database (65). A putative CaM-binding site was found between residues 224 and 244 of hENT1. CaM-binding sites are based on potential binding to bulky hydrophobic residues such as Phe, Val, Ile, Leu, or Trp in a number of different motifs (50). Comparisons to other CaM-interacting proteins and threading of the putative CaM-binding domain onto a Drosophila melanogaster myosin light chain kinase template led to the identification of Phe231, Tyr235, and Leu240 as putative interacting amino acids of Ca2+-loaded CaM and confirmed a putative 1-5-10 interaction motif (Fig. 2A). This potential CaM-binding site is within the long unstructured loop of ENT1 situated in the cytoplasm between transmembrane domains 6 and 7 (Fig. 2B), and modeling of this sequence suggested that the putative interacting amino acids could interact as typically predicted for calmodulin and its target proteins (Fig. 2C). Subsequently, a mENT1 bait was used to successfully screen ∼2 × 106 transformants from a NubG-X 11-day whole-mouse embryo library. Clones identified in the screen underwent bait validation (data not shown), and a total of 26 prey that interacted with the mENT1 bait were identified. All identified putative interactors, including calmodulin, are shown in Table 1. Putative interactors consisted of proteins found in a variety of locations and involved in a diversity of functions such as the plasma membrane-located G protein-coupled receptor, Gpbar1 (also known as TGR5), the cytoplasmic metabolic proteins such as glucose phosphate isomerase (GPI), the metabolic signaling protein such as myotrophin, and cytoplasmic cytoskeletal proteins such as tubulin. Intriguingly, a number of mitochondrial proteins were also identified as putative interactors, including the adenine nucleotide translocator, SLC25A4. Given our interest in calcium-dependent regulation of nucleoside transport, we focused on further analysis of the CaM-ENT1 interaction. Functionally and physiologically relevant interactions of any of the other identified putative interactors need to be confirmed by further studies.

Fig. 2.

Calmodulin (CaM)-binding site in equlibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1). A: sequence analysis of hENT1 and mENT1 identifies a 1-5-10 CaM-binding motif (amino acids highlighted in red) along with other confirmed CaM-binding sites. PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. B: location of the 1-5-10 motif within the large intracellular loop of ENT1. C: modeling of putative CaM/ENT1 loop region showing putative interacting amino acids.

Table 1.

List of putative mENT1 interactors

| Locus | Description |

|---|---|

| NM004905.2 | Peroxiredoxin 6 (PRDX6) |

| NM001013437.1 | SEH1-like protein (SEH1L) |

| NM003014.3 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 (SFRP4) |

| NM178014.2 | Tubulin, β (TUBB) |

| NM002084.3 | Glutathione peroxidase 3 (plasma) (GPX3) |

| NM006888.3 | Calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, δ) (CALM1) |

| NM024227.2 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L28 (Mrpl28) |

| NM000146.3 | Ferritin, light polypeptide (FTL) |

| NM000175.2 | Glucose phosphate isomerase (GPI) |

| NM175104.4 | RIKEN cDNA 2810012G03 gene (2810012G03Rik), |

| NM181509.1 | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 α (MAP1LC3A), transcript variant 2 |

| NM001020.4 | Ribosomal protein S16 (RPS16) |

| XM001472678.1 | Protein similar to β-globin, transcript variant 1 (LOC100044141) |

| NM148923.2 | Cytochrome b5 type A (microsomal) (CYB5A), transcript variant 1 |

| NM001151.2 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; adenine nucleotide translocator), member 4 (SLC25A4) |

| NM008218.1 | Hemoglobin α, adult chain 1 (Hba-a1) |

| NM145808.3 | Myotrophin (MTPN) |

| NM001539.2 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 1 (DNAJA1) |

| NM014034.2 | ASF1 anti-silencing function 1 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) (ASF1A) |

| NM000126.3 | Electron-transfer-flavoprotein, α polypeptide (ETFA) |

| NM028431.2 | Peptidase (mitochondrial processing) β (Pmpcb) |

| NM015409.3 | E1A binding protein p400 (EP400) |

| NM005498.4 | Adaptor-related protein complex 1, μ 2 subunit (AP1M2) |

| NM025797.2 | Cytochrome b5 (Cyb5) |

| NM001970.4 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A (EIF5A), transcript variant B |

| NM174985.1 | G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (Gpbar1) |

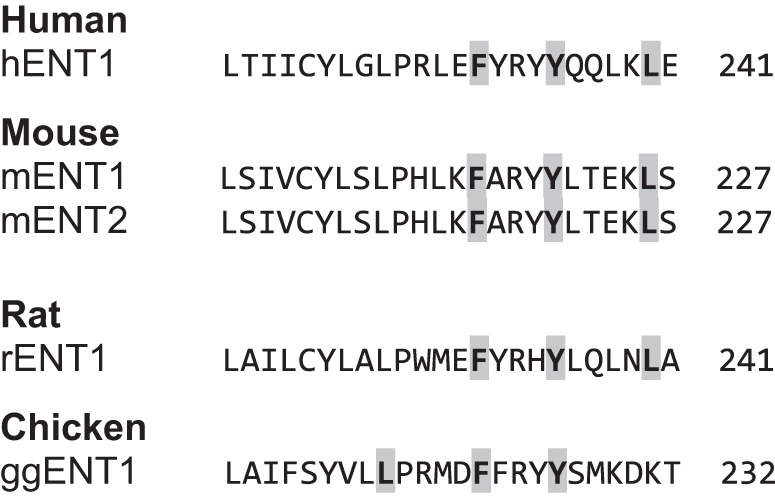

CaM binds to 1-5-10 interaction motif of ENT1-peptide.

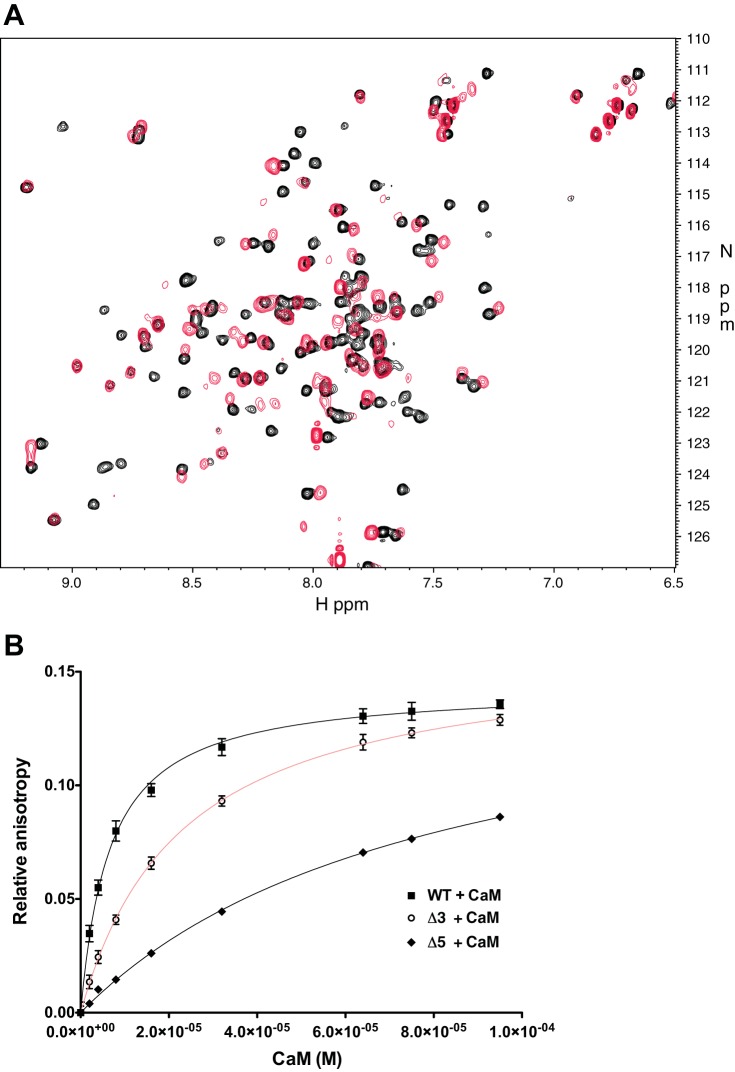

The putative 1-5-10 motif we identified in ENT1 is conserved in a number of other isoforms in other species (Fig. 3), in which calcium has been implicated as a regulator of nucleoside transport (e.g., chicken, 40; rat, 67; mouse, 63). We have previously confirmed that the intracellular loop between transmembrane domains 6 and 7 of ENT1 is generally unstructured and flexible (48), and we used NMR spectroscopy to confirm a biochemical interaction between CaM and hENT1. Because full-length hENT1 is highly hydrophobic and biochemically challenging to work with, we used a construct consisting of the intracellular loop for analyses. The large intracellular loop of hENT1 is predominantly unstructured, but binding of CaM is predicted to force a conformational change in the unstructured loop to an alpha-helical conformation. 15N-labeled CaM was titrated with the ubiquitin-hENT1 loop construct, and the limited amount of line broadening confirmed that the hENT1 loop binds to CaM (Fig. 4A) in the presence of calcium, similar to other studies that have examined the interaction of a protein domain with CaM (44).

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of human, mouse, rat, and chicken ENT isoforms (Clustal 2.1) showing conservation of the putative 1-5-10 CaM-binding site in species in which calcium regulation of nucleoside transport has been implicated.

Fig. 4.

CaM and the ENT1 loop interact in the presence of calcium via the 1-5-10 motif. A: heteronuclear single quantum coherence NMR spectra of CaM and hENT1 loop shows binding in the presence of calcium. Comparison of peaks representing CaM loaded with calcium (black) to CaM bound to hENT1 loop (red) indicates that a protein-protein interaction is occurring. B: mutation of the residues comprising the 1-5-10 motif of the hENT1-CaM interaction domain reduces affinity of CaM for the hENT1 loop. Fluorescence anisotropy confirms that wild-type (WT) hENT1 loop has a moderate affinity, Kd of 4.54 ± 0.57 μM (n = 4), whereas the ΔCaM-3 mutant has 5-fold lower affinity, Kd of 22.91 ± 1.62 μM (n = 3), confirming that mutation of the 1-5-10 motif abrogates the interaction between CaM and the CaM-binding region of hENT1. Moreover, the ΔCaM-5 mutant with 5 altered residues resulted in an even lower affinity with a Kd of 80.72 ± 6.13 μM (n = 3).

To confirm that the predicted interacting amino acids (Phe, Tyr, Leu) of the 1-5-10 CaM-ENT1 interaction motif actually interact with CaM, we used fluorescence anisotropy to measure the interaction between the wild-type version of this region of ENT1 and mutants in which the 1-5-10 motif was disrupted. The affinity of wild-type ENT1-loop and CaM was experimentally determined to be moderate (Kd = 4.54 ± 0.57 μM; n = 4), whereas the affinity of the ΔCaM-3 mutant (Phe, Tyr, Leu mutated to Ala) was reduced by fivefold (Kd = 22.91 ± 1.62 μM; n = 3), confirming that mutation of the 1-5-10 motif severely comprises the interaction between CaM and CaM-binding region of ENT1 (Fig. 4B). Mutation of five residues (ΔCaM-5) resulted in even lower affinity (Kd = 80.72 ± 6.13 μM; n = 3), likely attributable to the loss of compensatory interactions as a consequence of the hydrophobic tyrosines situated next to the 1-5 motif residues (Phe, Tyr). Interaction did not occur in the absence of calcium (data not shown).

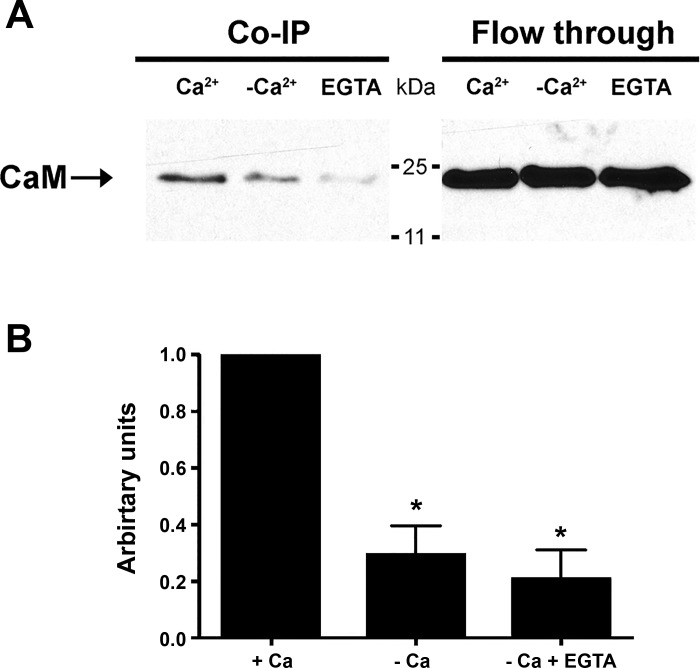

HA-hENT1 and CaM coimmunoprecipitate in the presence of calcium.

The loss of high-affinity binding for CaM to the interaction domain on hENT1 when the 1-5-10 domain was altered suggested that a CaM-hENT1 complex would form in the presence of calcium. To test this, anti-HA-conjugated agarose beads were loaded with HEK293 cell lysate expressing HA-hENT1. HA-ENT1 was immunoprecipitated with CaM in the presence of calcium, but this association was significantly reduced in the absence of supplementary calcium and by the addition of EGTA (Fig. 5A) to <20% of control levels based on densitometric analyses (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

CaM and ENT1 interact in presence of calcium. A: CaM is coimmunoprecipitated (Co-IP) with HA-ENT1 bait in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 (Ca2+ lane). Signal intensity is reduced with the absence of calcium (-Ca2+ lane) and virtually abolished in the presence of the calcium chelator EGTA (EGTA lane). The right side of the blot shows flow-through from same experiment. Representative blot, repeated 4 times with similar results (+Ca and -Ca n = 4, EGTA n = 2). B: densitometric analysis of immunoblots shows significant decrease in intensity of signal in the absence and/or chelation of calcium (pooled data, means ± SD, +Ca and -Ca n = 4, EGTA n = 2, *P < 0.05).

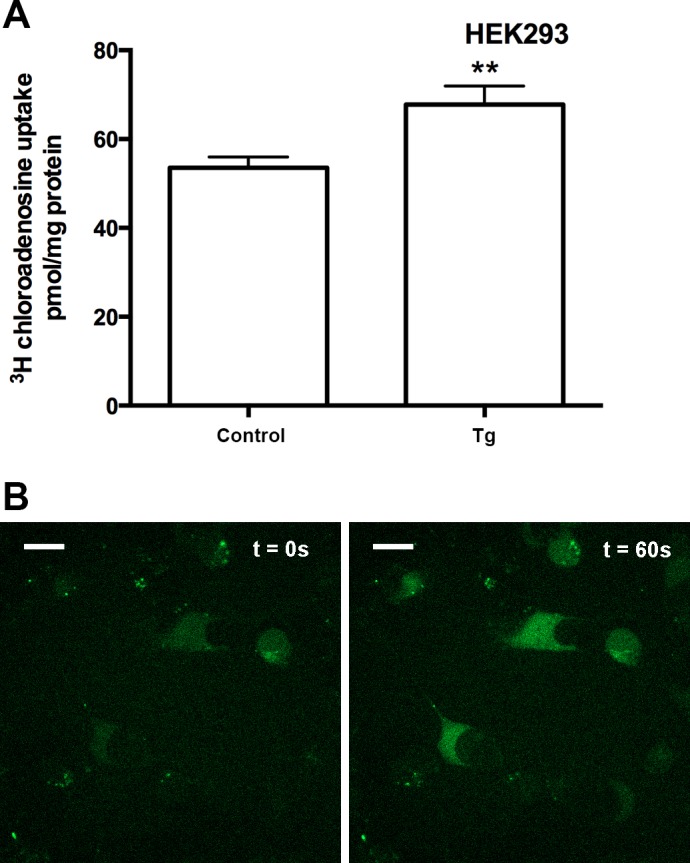

Increased intracellular calcium levels lead to increased sodium-independent nucleoside uptake.

Having confirmed that there was a biochemical interaction between CaM and hENT1, acting through a 1-5-10 motif within the large intracellular loop, we determined whether this was functionally significant. Our data show that reducing calcium in cells leads to lower levels of nucleoside flux, suggesting that varying calcium levels inside the cell results in modulation of nucleoside flux, so we hypothesized that increasing intracellular calcium would lead to an increased nucleoside uptake. To confirm this, we treated HEK293 cells with thapsigargin, a noncompetitive SERCA inhibitor that leads to a gradual [Ca2+]i increase in cells as they lose the ability to effectively sequester cytosolic calcium. Our data show that a brief (1 min) exposure of HEK293 cells to thapsigargin (1.5 μM) led to a significant increase (∼26%) in nucleoside transport (Fig. 6A) which was, intriguingly, comparable to the reduced transport (∼29%) seen with chelation of intracellular calcium (shown in Fig. 1). The increase in intracellular calcium levels stimulated by thapsigargin treatment was confirmed by calcium imaging and the calcium dye Fluo-4 (Fig. 6B). These data confirm that changes in intracellular calcium levels modulate ENT-dependent transport of nucleoside and nucleoside analog drugs in human cells.

Fig. 6.

Increasing intracellular calcium results in increased nucleoside transport. A: HEK293 cells were treated (1 min) in the presence or absence of 1.5 μM thapsigargin (Tg). Pooled data (n = 3) are shown with each condition conducted in sextuplicate, means ± SE (t-test, **P < 0.01). B: increased intracellular calcium level following 1.5 μM Tg treatment was confirmed with live cell imaging of HEK293 cells preloaded with Fluo-4 calcium indicator. HEK293 cells on glass-bottom dishes at 5% CO2 at 37°C were treated with 1.5 μM Tg (initial condition t = 0 s on left). Following treatment, fluorescent intensity (excited with 488 nm) gradually increased, and 1 min after treatment there was a substantial increase in fluorescence intensity (t = 60 s shown on right). The scale bars represent 20 μm.

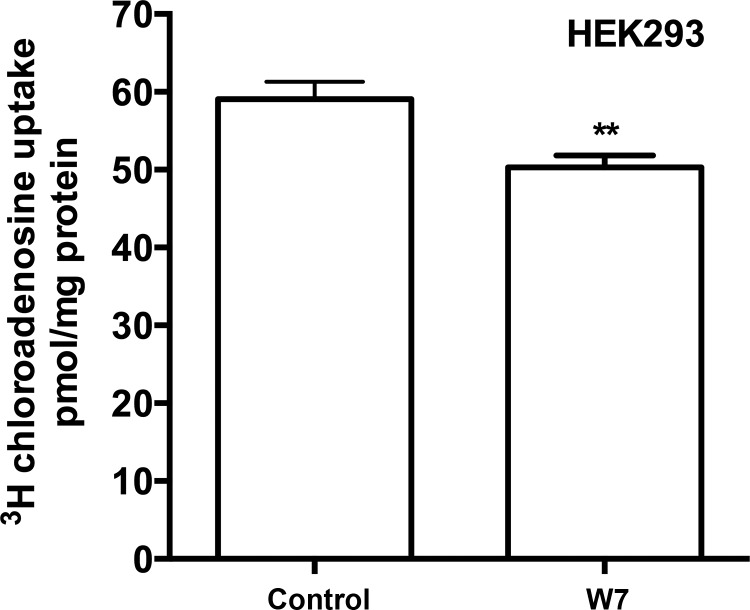

Blocking CaM binding reduces uptake of nucleosides.

After confirming there that was a calcium-dependent protein interaction between CaM and hENT1 and a calcium-dependent modulation of nucleoside flux, we hypothesized that the mechanism of regulation of ENT1 function was via protein-protein interactions between ENT1 and CaM. To confirm this, we treated HEK293 cells with W7, a cell-permeable antagonist of CaM that would disrupt an endogenous CaM-ENT1 interaction (39). Cells treated with W7 had significantly decreased sodium-independent nucleoside uptake compared with control (Fig. 7). These data corroborate our previous observations and suggest that calcium-dependent CaM-ENT1 interactions affect transporter function.

Fig. 7.

Blocking CaM interaction significantly reduces nucleoside transport. HEK293 cells treated for 1 min with Ca2+-containing buffer + 50 μM W7 had significantly less [3H]-2-chloroadenosine uptake compared with 0.075% DMSO control. Pooled data from 3 individual experiments (n = 3) are shown with each condition conducted in sextuplicate, presented as means ± SE (t-test, **P < 0.01).

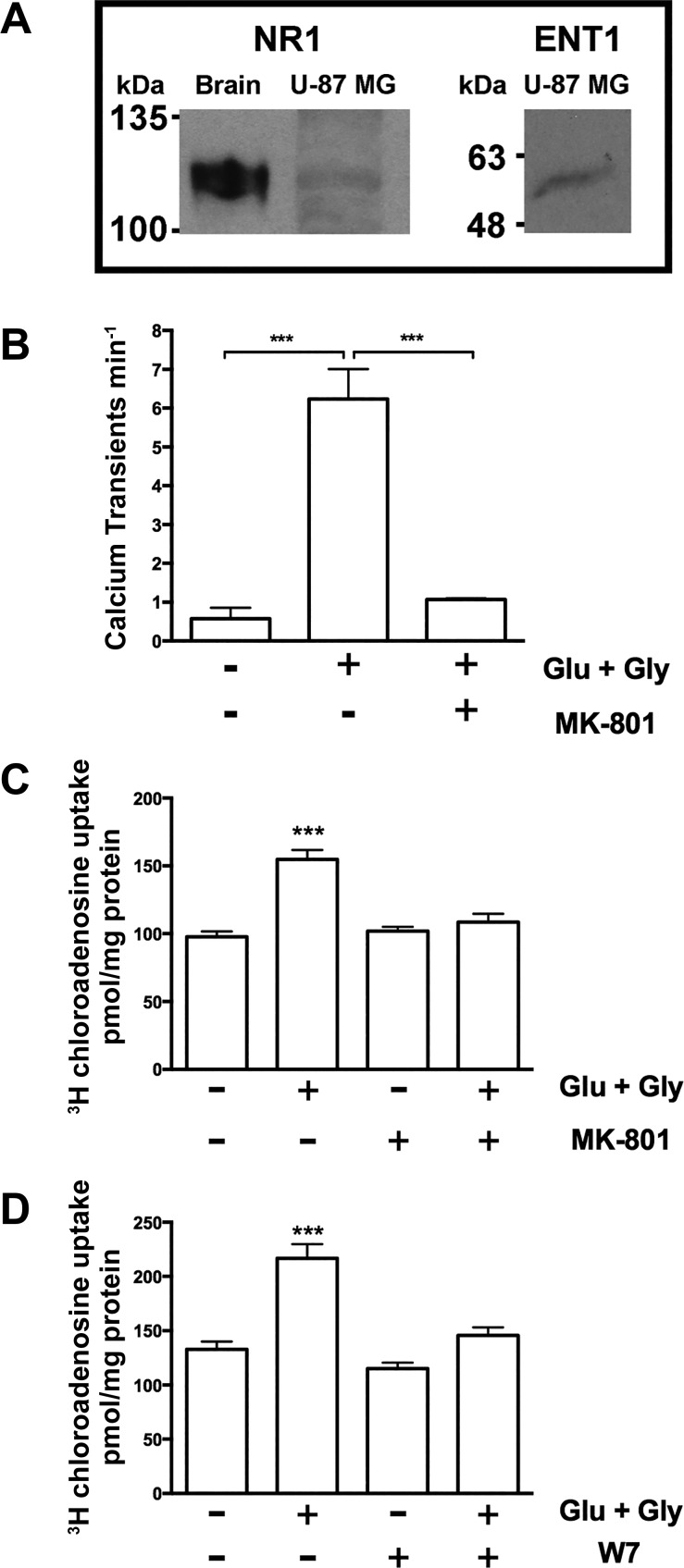

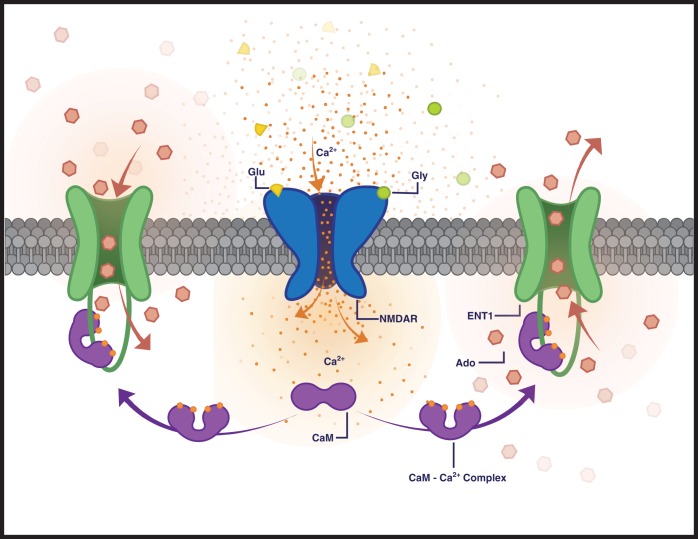

Increasing [Ca2+]i by NMDA receptor stimulation leads to increased ENT1-dependent transport but is blocked with treatment with NMDA receptor or CaM antagonists.

Manipulation of calcium levels and antagonizing CaM results in modulation of ENT-dependent nucleoside flux, supporting our hypothesis that ENT1 function is regulated by a Ca2+/CaM interaction. This mechanism explains previous observations made in cultured avian retinal cells (40), in which activation of glutamate receptors promotes a calcium-dependent and transporter-mediated release of purines, implying an important physiological link between glutamate signaling and ENT-dependent purine flux in the CNS. We therefore used the human cell line U-87 MG to determine whether glutamate receptor-activated calcium-dependent signaling leads to modulation of nucleoside uptake. We confirmed that these cells express NMDA receptor 1 and ENT1 (Fig. 8A). We then observed that stimulation of NMDA receptors by glutamate and glycine leads to an increase in intracellular calcium (Fig. 8B) and a significant increase in nucleoside uptake, which can be blocked by the NMDA antagonist MK-801 (Fig. 8C) and the CaM antagonist W7 (Fig. 8D). Taken together, these data confirm that ENT1 is subject to receptor-activated calcium-dependent calmodulin regulation, which can modulate the flux of both nucleosides and nucleoside analogs (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation leads to CaM-dependent increased nucleoside transport. A: Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of ENT1 and NMDA receptor 1 (NR1) protein in U-87 MG cells. A mouse synaptoneurosome preparation (0.5 μg protein loaded) was used as a control for NMDA receptor 1. Crude membrane preparations (100 μg protein loaded) of U-87 MG cells were used. Representative image is shown with the experiment repeated 3 times. B: Increased intracellular calcium levels in U-87 MG cells following glutamate (1 mM) and glycine (100 μM) treatment were confirmed by live cell imaging with cells preloaded with Fluo-4 calcium indicator (data not shown). Calcium transients in a field of view of a plate of U-87 MG cells on glass-bottom dishes at 5% (vol/vol) CO2 at 37°C were quantified at basal levels (in HBSS following 20-min incubation), then imaged in HBSS containing glutamate (1 mM) and glycine (100 μM) for 10 min, and then imaged following the addition of the NMDA receptor inhibitor MK-801 (50 μM). Bars represent means ± SD of pooled data from 3 independent experiments (1-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison post hoc test, ***P < 0.001). Glycine (100 μM) treatment alone had no effect in the twice-repeated experiment (data not shown). C: U-87 MG cells were pretreated for 10 min with HBSS and then treated for 20 min with or without glutamate (1 mM) and glycine (100 μM) in the presence or absence of MK-801 (50 μM) in HBSS. Pooled data from 3 individual experiments (n = 3), with each condition conducted in sextuplicate, are represented as means ± SE (1-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison post hoc test, ***P < 0.001). D: U-87 MG cells were pretreated for 10 min with HBSS and then treated for 20 min with or without 1 mM glutamate and 100 μM glycine in the presence or absence of W7 (50 μM) in HBSS. Pooled data from 3 individual experiments (n = 3), with each condition conducted in sextuplicate, are represented as means ± SE (1-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison post hoc test, ***P < 0.001).

Fig. 9.

ENT1 is regulated by receptor-stimulated calcium signaling to modulate nucleoside flux. This cartoon depicts a putative model for receptor-dependent regulation of adenosine transport involving NMDA receptors, CaM and ENT1. Glutamate/glycine stimulation of NMDA receptors leads to calcium influx, resulting in local increases in intracellular calcium and calcium binding to CaM, which results in a shift from apo-CaM to a Ca2+/CaM complex. CaM binds to ENT1 (in the presence of increased calcium), leading to an increase in nucleoside flux, which can result in either increased nucleoside uptake (left) or increased nucleoside release (right) depending on the endogenous adenosine concentration gradient.

DISCUSSION

The cloning of the first equilibrative nucleoside transporter, hENT1 (47), led to interest in understanding underlying regulatory mechanisms and physiological importance of this prototypic isoform, in nucleoside analog drug delivery and purinergic signaling in the cardiovascular and central nervous systems (23, 51, 52, 54). As a component of the purinome, it is likely that ENT1 is subject to feedback regulation by several signaling pathways via a variety of mechanisms (54). We hypothesized that protein-protein interactions are likely to play a role in regulation of ENT1 and speculated that calcium-related proteins might be good candidates for interactors. Therefore, we undertook a study to identify and characterize putative interactors using the MYTH approach. MYTH screening is specifically designed for membrane proteins such as transporters and identifies a range of putative interactors, representing a diversity of functions. Although we cannot confirm at this point that all these putative interactors represent physiologically relevant partners for ENT1, our data suggest that ENT1 may interact with a variety of proteins, possibly in the form of a protein complex or a metabolon.

The presence of CaM among the putative interactors suggested that our prediction that protein-protein interactions might underlie previous observations (40, 63) of calcium-dependent regulation of nucleoside flux might be correct. We confirmed the site of interaction between CaM and ENT1 as a 1-5-10 motif, which is located in the large intracellular loop between transmembrane domains 6 and 7. The large loop was identified as a potential regulatory target when ENT1 was first cloned (25), and many subsequent studies have suggested that this region is important functionally or in terms of regulation (4, 6, 45, 49, 62). However, this is the first report to demonstrate a biochemical interaction with another protein, and we confirmed that amino acids phenylalanine 231, tyrosine 235, and leucine 240 contribute to the transient interactions between the ENT1 loop and calmodulin, in the presence of calcium, to regulate ENT1. Moreover, previous studies demonstrating the regulation of nucleoside flux by calcium have been done in models (rat, mouse, chicken) that also possess ENTs with the 1-5-10 motif in the large intracellular loop, shown here to be involved in calcium-dependent CaM regulation of ENT1 (Fig. 9). The presence of a putative CaM-binding site in ENT1 isoforms in other vertebrates in this region suggests that Ca2+/CaM regulation of equilibrative nucleoside transport is perhaps widely distributed phylogenetically and thus likely to be a fundamental mechanism of regulation of this protein family.

Calcium levels and adenosine levels have previously been shown to affect each other (21, 43, 57). To reduce potentially confounding effects of regulation of purine nucleoside metabolism by calcium, we routinely conducted transport analyses within the linear phase of transport (before permeant concentration reaching equilibrium), thereby ensuring that we focused our attention on the regulation of transport rather than metabolism of the substrate.

A number of studies have implicated calcium as a potential regulatory component of a poorly understood feedback mechanism that regulates nucleoside flux. It is well established that NMDA-type receptor activation results in a rapid increase in intracellular calcium, leading to a wide variety of effects, and that NMDA-type glutamate receptor-activated Ca2+/CaM-dependent CaMKIIs are key regulators of synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory (28). Intriguingly, it is now clear that ENT1 plays a significant role in a variety of purinergic- and glutamatergic-dependent behavioral responses because ENT1 knockout mice show altered goal-directed behaviors and altered addictive responses to ethanol (8, 9, 38). The findings presented in this paper provide a mechanistic basis for previous observations in cultured avian retinal cells and mouse hippocampal slices (40, 63) in which glutamate receptor-activated calcium influx leads to enhanced efflux of nucleosides via ENT1 (in a process that involves CAMKII in avian cells). Moreover, our findings may provide an explanation for the glutamatergic and adenosinergic-dependent behavioral effects noted in ENT1 knockout mice.

The existence of calcium-regulated ENT1 supports a model that incorporates a feedback relationship between receptor-coupled (NMDA-type glutamate or other) calcium signaling, CaM binding, and altered ENT1 function, leading to modulation of extracellular adenosine levels and subsequent adenosine receptor signaling events. Because Ca2+/CaM modulation of ENT1 exists in different cell types, this regulation may be widely distributed and perhaps universal for this isoform. Regulation of membrane transport activity by direct interaction of Ca2+/CaM has been shown for other SLC families, such as SLC9A7, in which identification and characterization of the interactome (33) suggest Ca2+/CaM regulation.

A number of consensus kinase target sites and a number of studies have inferred a role for phosphorylation or kinase-dependent processes in regulation of ENTs (4, 7, 11, 12, 40, 45). CaM-dependent phosphorylation of a plasma membrane solute carrier has been previously described for aquaporin-0 (AQ0), a water and small solute channel exclusively expressed in eye lens cells, and the underlying mechanism of regulation has been identified (47). Our research has shown that the large intracellular loop of ENT1 can be phosphorylated (in vitro and ex vivo) directly (49) by PKC and PKA, suggesting that this is a potential regulatory mechanism, although no functional correlate has yet been found. Intriguingly, a role for CaMKII has been identified in regulation of adenosine flux via ENT1 in avian retinal cells (40). Consensus sites are not well conserved between species, and a convincing CaMKII target site was not identified in the mammalian sequences. However, CaMKII and phosphatases can mutually inhibit each other (24), and a role for PP1/2A in regulating the ethanol sensitivity (which is kinase dependent) of the adenosine transporter in neuronal cells (12) has been reported. Taken together, these data suggest that CaMKII could regulate ENT1 via phosphatase-dependent removal of phosphorylation sites, such as Ser279 and 286 and Thr274 (49), which are located in the second half of the large intracellular loop, whereas the CaM-binding domain resides in the proximal part of the loop. Thus, as intracellular calcium levels rise, CaM interacts with the ENT1 loop, altering the conformation of the previously unstructured loop and possibly changing accessibility of the phosphorylation sites. Functional consequences of this regulation are changes in overall rates of nucleoside flux.

ENT1 plays a major role in the efficacy of uptake of a large class of drugs used in a variety of clinical settings. It is also the target of drugs used to treat cardiac arrhythmias and other conditions. Consequently, a deeper understanding of the regulation of ENT1 may have positive implications for improved chemotherapeutics. Presence of ENT1 protein or mRNA has been reported as being a predictive indicator for sensitivity to nucleoside analog drugs (1, 35, 53, 58) but also as having no correlation to response (2). Relative levels (either protein or mRNA) of ENT1 may not be accurate correlates of drug response, especially if “low” levels of protein can be activated to enhance update of drug and amplify effects. Indeed, proteins involved in calcium-dependent signaling have been reported to be significantly overexpressed/upregulated in gemcitabine-sensitive pancreatic cells and downregulated in resistant cells in the absence of any observed change in levels of nucleoside transporters (10), and here we demonstrate in a bladder cancer cell line that antagonism of CaM results in reduced uptake of the nucleoside analog drug, gemcitabine. Thus modulation of Ca2+/CaM-dependent signaling by manipulation of [Ca2+]i may either enhance or compromise the efficacy of nucleoside analog drugs depending on the nature of the calcium effect. This may be particularly important in clinical situations in which multiple drugs (e.g., nucleoside analogs and blood pressure medication) are involved.

In summary, we have used a variety of novel techniques to identify the first set of putative interactors for ENT1. These putative interactors span a variety of proteins, raising the possibility of multiple interacting partners across a range of protein types. Moreover, we have confirmed that CaM binds to a defined region of the large intracellular loop of ENT1 in a calcium-dependent manner, suggesting that calcium signaling is a regulatory mechanism controlling some aspect of ENT1 behavior. We have also described a novel receptor-dependent regulatory mechanism whereby intracellular calcium modulates nucleoside and nucleoside analog drug uptake via CaM-dependent interaction of ENT1. This report is the first to provide a mechanistic basis to explain calcium signaling-dependent regulation of nucleoside flux and provides novel insights into the importance of calcium in the varied roles of the SLC29 family.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a grant to I. Coe from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (grant no. 203397-2011-RGPIN). I. Coe also acknowledges the financial support of Ryerson University. The work in the Stagljar laboratory is supported by grants from the Ontario Genomics Institute, Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Canadian Cancer Society, Pancreatic Cancer Canada, CQDM/Explore, and University Health Network.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.B., P.M., Z.N., V.W., L.D., I.S., and I.R.C. conception and design of research; A.B., P.M., Z.N., V.W., and L.D. performed experiments; A.B., P.M., Z.N., V.W., L.D., I.S., and I.R.C. analyzed data; A.B., P.M., Z.N., L.D., I.S., and I.R.C. interpreted results of experiments; A.B., P.M., and I.R.C. prepared figures; A.B. and I.R.C. drafted manuscript; A.B., Z.N., and I.R.C. edited and revised manuscript; A.B., P.M., Z.N., V.W., L.D., I.S., and I.R.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Amy Ramsey provided mouse brain tissue, and Catharine Mielnik provided assistance with optimizing NMDA receptor Western blots. Dr. Mitsu Ikura provided the CaM vector. Dr. Vivian Saridakis provided assistance with the NMR analysis and presentation of data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achiwa H, Oguri T, Sato S, Maeda H, Niimi T, Ueda R. Determinants of sensitivity and resistance to gemcitabine: the roles of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 and deoxycytidine kinase in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 95: 753–757, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock AJ, Dong HP, Tropé CG, Staff AC, Risberg B, Davidson B. Nucleoside transporters are widely expressed in ovarian carcinoma effusions. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 69: 467–475, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boleti H, Coe IR, Baldwin SA, Young JD, Cass CE. Molecular identification of the equilibrative NBMPR-sensitive (es) nucleoside transporter and demonstration of an equilibrative NBMPR-insensitive (ei) transport activity in human erythroleukemia (K562) cells. Neuropharmacology 36: 1167–1179, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone DB, Robillard KR, Stolk M, Hammond JR. Differential regulation of mouse equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (mENT1) splice variants by protein kinase CK2. Mol Membr Biol 24: 294–303, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canet D, Doering K, Dobson CM, Dupont Y. High-sensitivity fluorescence anisotropy detection of protein-folding events: application to alpha-lactalbumin. Biophys J 80: 1996–2003, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cano-Soldado P, Pastor-Anglada M. Transporters that translocate nucleosides and structural similar drugs: structural requirements for substrate recognition. Med Res Rev 32: 428–457, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudary N, Naydenova Z, Shuralyova I, Coe IR. The adenosine transporter, mENT1, is a target for adenosine receptor signaling and protein kinase Cϵ in hypoxic and pharmacological preconditioning in the mouse cardiomyocyte cell line, HL-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310: 1190–1198, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Nam HW, Lee MR, Hinton DJ, Choi S, Kim T, Kawamura T, Janak PH, Choi DS. Altered glutamatergic neurotransmission in the striatum regulates ethanol sensitivity and intake in mice lacking ENT1. Behav Brain Res 208: 636–642, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Rinaldo L, Lim SJ, Young H, Messing RO, Choi DS. The type 1 equilibrative nucleoside transporter regulates anxiety-like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav 6: 776–783, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YW, Liu JY, Lin ST, Li JM, Huang SH, Chen JY, Wu JY, Kuo CC, Wu CL, Lu YC, Chen YH, Fan CY, Huang PC, Law CH, Lyu PC, Chou HC, Chan HL. Proteomic analysis of gemcitabine-induced drug resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Biosyst 7: 3065–3074, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coe I, Zhang Y, McKenzie T, Naydenova Z. PKC regulation of the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter, hENT1. FEBS Lett 517: 201–205, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coe IR, Yao L, Diamond I, Gordon AS. The role of protein kinase C in cellular tolerance to ethanol. J Biol Chem 271: 29468–29472, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ducret T, Vacher AM, Vacher P. Voltage-dependent ionic conductances in the human malignant astrocytoma cell line U87-MG. Mol Membr Biol 20: 329–343, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dzamba D, Honsa P, Anderova M. NMDA receptors in glial cells: pending questions. Curr Neuropharmacol 11: 250–262, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckle T, Hughes K, Ehrentraut H, Brodsky KS, Rosenberger P, Choi DSS, Ravid K, Weng T, Xia Y, Blackburn MR, Eltzschig HK. Crosstalk between the equilibrative nucleoside transporter ENT2 and alveolar Adora2b adenosine receptors dampens acute lung injury. FASEB J 27: 3078–3089, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edrington TC, Yeagle PL, Gretzula CL, Boesze-Battaglia K. Calcium-dependent association of calmodulin with the C-terminal domain of the tetraspanin protein peripherin/rds. Biochemistry 46: 3862–3871, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endres CJ, Moss AM, Govindarajan R, Choi DSS, Unadkat JD. The role of nucleoside transporters in the erythrocyte disposition and oral absorption of ribavirin in the wild-type and equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1-/- mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331: 287–296, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Errasti-Murugarren E, Pastor-Anglada M. Drug transporter pharmacogenetics in nucleoside-based therapies. Pharmacogenomics 11: 809–841, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fetchko M, Stagljar I. Application of the split-ubiquitin membrane yeast two-hybrid system to investigate membrane protein interactions. Methods 32: 349–362, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerwins P, Fredholm BB. ATP and its metabolite adenosine act synergistically to mobilize intracellular calcium via the formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate in a smooth muscle cell line. J Biol Chem 267: 16081–16087, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol 350: 87–96, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grenz A, Bauerle JD, Dalton JH, Ridyard D, Badulak A, Tak E, McNamee EN, Clambey E, Moldovan R, Reyes G, Klawitter J, Ambler K, Magee K, Christians U, Brodsky KS, Ravid K, Choi DSS, Wen J, Lukashev D, Blackburn MR, Osswald H, Coe IR, Nürnberg B, Haase VH, Xia Y, Sitkovsky M, Eltzschig HK. Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1) regulates postischemic blood flow during acute kidney injury in mice. J Clin Invest 122: 693–710, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Grey KB, Burrell BD. Co-induction of LTP and LTD and its regulation of protein kinases and phosphatases. J Neurophysiol 103: 2737–2746, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths M, Beaumont N, Yao SY, Sundaram M, Boumah CE, Davies A, Kwong FY, Coe I, Cass CE, Young JD, Baldwin SA. Cloning of a human nucleoside transporter implicated in the cellular uptake of adenosine and chemotherapeutic drugs. Nat Med 3: 89–93, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grycova L, Holendova B, Lansky Z, Bumba L, Jirku M, Bousova K, Teisinger J. Ca(2+) binding protein S100A1 competes with calmodulin and PIP2 for binding site on the C-terminus of the TPRV1 receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 6: 386–392, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gusella M, Pasini F, Bolzonella C, Meneghetti S, Barile C, Bononi A, Toso S, Menon D, Crepaldi G, Modena Y, Stievano L, Padrini R. Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 genotype, cytidine deaminase activity and age predict gemcitabine plasma clearance in patients with solid tumours. Br J Clin Pharmacol 71: 437–444, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hell JW. CaMKII: claiming center stage in postsynaptic function and organization. Neuron 81: 249–265, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hillgren KM, Keppler D, Zur AA, Giacomini KM, Stieger B, Cass CE, Zhang L. Emerging transporters of clinical importance: an update from the International Transporter Consortium. Clin Pharmacol Ther 94: 52–56, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes SJ, Cravetchi X, Vilas G, Hammond JR. Adenosine A1 receptor activation modulates human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) activity via PKC-mediated phosphorylation of serine-281. Cell Signal 27: 1008–1018, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jessard P, Attard JJ, Carpenter TA, Hall LD. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging in the solid state. Prog Nucl Mag Res Spect 23: 1–41, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y, Jakovcevski M, Bharadwaj R, Connor C, Schroeder FA, Lin CL, Straubhaar J, Martin G, Akbarian S. Setdb1 histone methyltransferase regulates mood-related behaviors and expression of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. J Neurosci 30: 7152–7167, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kagami T, Chen S, Memar P, Choi M, Foster LJ, Numata M. Identification and biochemical characterization of the SLC9A7 interactome. Mol Membr Biol 25: 436–447, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King AE, Ackley MA, Cass CE, Young JD, Baldwin SA. Nucleoside transporters: from scavengers to novel therapeutic targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27: 416–425, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klanova M, Lorkova L, Vit O, Maswabi B, Molinsky J, Pospisilova J, Vockova P, Mavis C, Lateckova L, Kulvait V, Vejmelkova D, Jaksa R, Hernandez F, Trneny M, Vokurka M, Petrak J, Klener P Jr. Downregulation of deoxycytidine kinase in cytarabine-resistant mantle cell lymphoma cells confers cross-resistance to nucleoside analogs gemcitabine, fludarabine and cladribine, but not to other classes of anti-lymphoma agents. Mol Cancer 13: 159, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam MHY, Snider J, Rehal M, Wong V, Aboualizadeh F, Drecun L, Wong O, Jubran B, Li M, Ali M, Jessulat M, Deineko V, Miller R, Lee M, Park HO, Davidson A, Babu M, Stagljar IA. A comprehensive membrane interactome mapping of Sho1p reveals Fps1p as a novel key player in the regulation of the HOG pathway in S. cerevisiae. J Mol Biol 427: 2088–2103, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, Banasr M, Dwyer JM, Iwata M, Li XY, Aghajanian G, Duman RS. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 329: 959–964, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nam HW, Hinton DJ, Kang NY, Kim T, Lee MR, Oliveros A, Adams C, Ruby CL, Choi DS. Adenosine transporter ENT1 regulates the acquisition of goal-directed behavior and ethanol drinking through A2A receptor in the dorsomedial striatum. J Neurosci 33: 4329–4338, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osawa M, Swindells MB, Tanikawa J, Tanaka T, Mase T, Furuya T, Ikura M. Solution structure of calmodulin-W-7 complex: the basis of diversity in molecular recognition. J Mol Biol 276: 165–176, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paes-de-Carvalho R, Dias BV, Martins RA, Pereira MR, Portugal CC, Lanfredi C. Activation of glutamate receptors promotes a calcium-dependent and transporter-mediated release of purines in cultured avian retinal cells: possible involvement of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Neurochem Int 46: 441–451, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palygin O, Lalo U, Pankratov Y. Distinct pharmacological and functional properties of NMDA receptors in mouse cortical astrocytes. Br J Pharmacol 163: 1755–1766, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palygin O, Lalo U, Verkhratsky A, Pankratov Y. Ionotropic NMDA and P2X1/5 receptors mediate synaptically induced Ca2+ signalling in cortical astrocytes. Cell Calcium 48: 225–231, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peakman MC, Hill SJ. Adenosine A1 receptor-mediated changes in basal and histamine-stimulated levels of intracellular calcium in primary rat astrocytes. Br J Pharmacol 115: 801–810, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piazza M, Guillemette JG, Dieckmann T. Chemical shift perturbations induced by residue specific mutations of CaM interacting with NOS peptides. Biomol NMR Assign 9: 299–302, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramadan A, Naydenova Z, Stevanovic K, Rose JB, Coe IR. The adenosine transporter, ENT1, in cardiomyocytes is sensitive to inhibition by ethanol in a kinase-dependent manner: implications for ethanol-dependent cardioprotection and nucleoside analog drug cytotoxicity. Purinergic Signal 10: 305–312, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramaswamy P, Aditi Devi N, Hurmath Fathima K, Dalavaikodihalli Nanjaiah N. Activation of NMDA receptor of glutamate influences MMP-2 activity and proliferation of glioma cells. Neurol Sci 35: 823–829, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reichow SL, Clemens DM, Freites JA, Németh-Cahalan KL, Heyden M, Tobias DJ, Hall JE, Gonen T. Allosteric mechanism of water-channel gating by Ca2+-calmodulin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 1085–1092, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reyes G, Chalsev M, Nivillac NMI, Coe IR. Analysis of recombinant tagged equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1) expressed in E. coli. Biochem Cell Biol 89: 246–255, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reyes G, Nivillac NM, Karim MZ, Desouza L, Siu KW, Coe IR. The equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT1) can be phosphorylated at multiple sites by PKC and PKA. Mol Membr Biol 28: 412–426, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rhoads AR, Friedberg F. Sequence motifs for calmodulin recognition. FASEB J 11: 331–340, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rose JB, Coe IR. Physiology of nucleoside transporters: back to the future. Physiology 23: 41–48, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rose JB, Naydenova Z, Bang A, Eguchi M, Sweeney G, Choi DSS, Hammond JR, Coe IR. Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 plays an essential role in cardioprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H771–H777, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santini D, Schiavon G, Vincenzi B, Cass CE, Vasile E, Manazza AD, Catalano V, Baldi GG, Lai R, Rizzo S, Giacobino A, Chiusa L, Caraglia M, Russo A, Mackey J, Falcone A, Tonini G. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) levels predict response to gemcitabine in patients with biliary tract cancer (BTC). Curr Cancer Drug Targets 11: 123–129, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santos-Rodrigues Dos A, Grañé-Boladeras N, Bicket A, Coe IR. Nucleoside transporters in the purinome. Neurochem Int 73: 229–237, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snider J, Hanif A, Lee ME, Jin K, Yu AR, Chuk M, Damjanovic D, Graham C, Wierzbicka M, Tang P, Balderes D, Wong V, San Luis BJ, Shevelev I, Sturley SL, Boone C, Babu M, Zhang Z, Paumi CM, Park HO, Michaelis S, Stagljar I. Mapping the functional yeast ABC transporter interactome. Nat Chem Biol 9: 565–572, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snider J, Kittanakom S, Damjanovic D, Curak J, Wong V, Stagljar I. Detecting interactions with membrane proteins using a membrane two-hybrid assay in yeast. Nat Protoc 5: 1281–1293, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spirli C, Locatelli L, Fiorotto R, Morell CM, Fabris L, Pozzan T, Strazzabosco M. Altered store operated calcium entry increases cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate production and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 phosphorylation in polycystin-2-defective cholangiocytes. Hepatology 55: 856–868, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 58.Spratlin JL, Mackey JR. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: towards individualized treatment decisions. Cancers (Basel) 2: 2044–2054, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stagljar I, Korostensky C, Johnsson N, te Heesen S. A new genetic system based on split-ubiquitin for the analysis of interactions between membrane proteins in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 5187–5192, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stepulak A, Luksch H, Gebhardt C, Uckermann O, Marzahn J, Sifringer M, Rzeski W, Staufner C, Brocke KS, Turski L, Ikonomidou C. Expression of glutamate receptor subunits in human cancers. Histochem Cell Biol 132: 435–445, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takano T, Lin JH, Arcuino G, Gao Q, Yang J, Nedergaard M. Glutamate release promotes growth of malignant gliomas. Nat Med 7: 1010–1015, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valdés R, Elferich J, Shinde U, Landfear SM. Identification of the intracellular gate for a member of the equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) family. J Biol Chem 289: 8799–8809, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wall MJ, Dale N. Neuronal transporter and astrocytic ATP exocytosis underlie activity-dependent adenosine release in the hippocampus. J Physiol 591: 3853–3871, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weber JF, Waldman SD. Calcium signaling as a novel method to optimize the biosynthetic response of chondrocytes to dynamic mechanical loading. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 13: 1387–1397, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yap KL, Kim J, Truong K, Sherman M, Yuan T, Ikura M. Calmodulin target database. J Struct Funct Geonomics 1: 8–14, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Young JD, Yao SY, Baldwin JM, Cass CE, Baldwin SA. The human concentrative and equilibrative nucleoside transporter families, SLC28 and SLC29. Mol Aspects Med 34: 529–547, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zamzow CR, Bose R, Parkinson FE. N-methyl-d-aspartate-evoked adenosine and inosine release from neurons requires extracellular calcium. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 87: 850–858, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zimmerman MA, Tak E, Ehrentraut SF, Kaplan M, Giebler A, Weng T, Choi DSS, Blackburn MR, Kam I, Eltzschig HK, Grenz A. Equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT)-1-dependent elevation of extracellular adenosine protects the liver during ischemia and reperfusion. Hepatology 58: 1766–1778, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]