Abbreviations

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- BM

Bethlem myopathy

- CK

creatine kinase

- CMAP

compound muscle action potentials

- COL6A1

collagen, type VI, alpha 1

- COL6A2

collagen, type VI, alpha 2

- COL6A3

collagen, type VI, alpha 3

- COL6

collagen, type VI

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EMG

electromyography

- GLDH

glutamate dehydrogenase

- NADH‐TR

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide‐tetrazolium reductase

- PTPLA

protein tyrosine phosphatase‐like (proline instead of catalytic arginine) member A

- SSCD

sarcolemma‐specific collagen VI deficiency

- UCMD

Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy

An 11‐month‐old female spayed Labrador Retriever was presented for examination because of progressive gait abnormality and multiple joint deformities of approximately 6 months' duration. Mild intermittent lameness of the left thoracic limb was first noticed after exercise when the dog was approximately 5 months of age. Within a month, the lameness had progressed to affect the contralateral thoracic limb. Radiographs of both thoracic limbs revealed a mild mid‐diaphyseal varus angulation of the antebrachia. Radiographs of the pelvic limbs revealed moderate right‐sided coxofemoral subluxation. At 9 months of age, the dog developed an abnormal pelvic limb posture with bilateral tarsal hyperextension. Resistance to manipulation of multiple limb joints was noted. Synoviocentesis of the right stifle and tarsus was performed and showed slight hyperplasia and hypertrophy of synovial lining cells and negative aerobic and anaerobic culture. Antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor titers were negative. Initial treatment with robenacoxib, at a dose of 1 mg/kg PO q24 h resulted in minimal improvement in function. Treatment with tapering doses of prednisolone (10 mg PO q24 h for 5 days, then 5 mg PO q24 h for 5 days, and then 5 mg PO q48 h for 20 days) led to mild gait improvement and range of motion in the affected joints; however, the dog showed progressive difficulty in walking and continuation of the abnormal posture with bilateral carpal and tarsal hyperextension. Serology for Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum was negative. Hydrotherapy and alternating treatment with robenacoxib and prednisolone were continued until referral at the age of 11 months.

On examination the dog appeared small in size (body weight 23 kg). The gait was hypometric in all 4 limbs (Video S1). Hyperextension of both carpi, both tarsi, and both stifles was noted (Fig 1). Moderate pelvic and thoracic limb muscle atrophy was apparent and there was moderate bilaterally symmetrical atrophy of the temporalis muscles. Manipulation of the coxofemoral and stifle joints was moderately resisted. Range of motion in the carpi and tarsi was moderately reduced in flexion. Joint laxity was not evident; however, the flat‐footed stance suggested possible laxity of the digital flexor tendons (Fig 1, Video S1). Neurologic examination revealed normal thoracic withdrawal and myotatic reflexes. Pelvic limb withdrawal and patellar reflexes were mildly reduced.

Figure 1.

Three‐year‐old female spayed Labrador Retriever with collagen VI‐related myopathy. Note the hyperextension of the tarsus and stifle, and flat‐footed stance.

Hematology and biochemistry revealed a mild increase in potassium at 6.3 mmol/L (reference range 3.5–6.0), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 131 U/L (reference range 0–50), alanine transaminase (ALT) 124 U/L (reference range 0–25), glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH) 15 U/L (reference range 0–10), and creatine kinase (CK) 907 U/L (reference range 0–190). The DNA test for hereditary centronuclear myopathy in Labrador retrievers was negative for the PTPLA mutation.1, 1 Electrodiagnostic testing included electromyography (EMG) of the majority of the muscles on the right side of the body including the temporalis muscle and measurement of the motor nerve conduction velocities of the right sciatic‐tibial and left ulnar nerves. EMG revealed spontaneous activity in the gastrocnemius and gluteal muscles. Motor nerve conduction velocities of the left ulnar nerve between the carpus and elbow, and the right sciatic‐tibial nerve, were mildly decreased at 44.7 m/s (60 ± 1.7 m/s) and 51.4 m/s (60 ± 1.1 m/s), respectively.2 The compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) had a normal biphasic or triphasic shape and amplitude, except for CMAPs elicited from the tibial funiculus that had a decreased amplitude, suggesting a myopathy. On the basis of the clinical history, neurologic examination, and electrodiagnostic findings, a generalized myopathy was suspected.

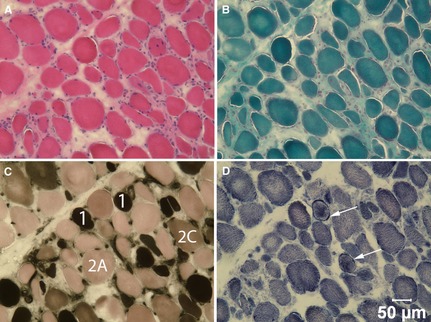

Unfixed and fixed (10% buffered formaldehyde) biopsies were collected from the left biceps femoris and temporalis muscles. The unfixed biopsies were flash frozen in isopentane precooled in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further processed by a standard panel of histochemical stains and reactions.3 The fixed biopsies were processed in paraffin. Similar pathologic changes were found in both muscles and illustrated for the biceps femoris (Fig 2). An excessive variability in myofiber size was noted with sizes ranging from 12 to 50 μm in diameter. Atrophic fibers had a round shape and many contained internal nuclei (Fig 2A). Endomysial fibrosis was prominent (Fig 2B). Atrophic fibers were of both fiber types with excessive numbers of type 2C fibers (Fig 2C). The oxidative enzyme reaction NADH‐TR showed an uneven pattern of staining with peripheral aggregation of stain in some fibers similar to lobulated fibers (Fig 2D). Small numbers of necrotic fibers were also present with some undergoing phagocytosis. Multifocal areas of mild mixed mononuclear cell infiltrations were present having an endomysial distribution. A noninflammatory myopathy with mild myonecrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration, or a form of muscular dystrophy was suspected. Additional investigations were performed including immunofluorescence staining and electron microscopy.

Figure 2.

Cryosections from the biceps femoris muscle were stained with H&E (A) and modified Gomori trichrome (B), and reacted with myofibrillar ATPase at pH 4.3 (C) and NADH‐TR (D). Type 1, 2A and 2C fibers are labeled in image c and arrows denote sarcolemmal deposits of NADH‐TR positive material in d. Bar = 50 μm for a–d.

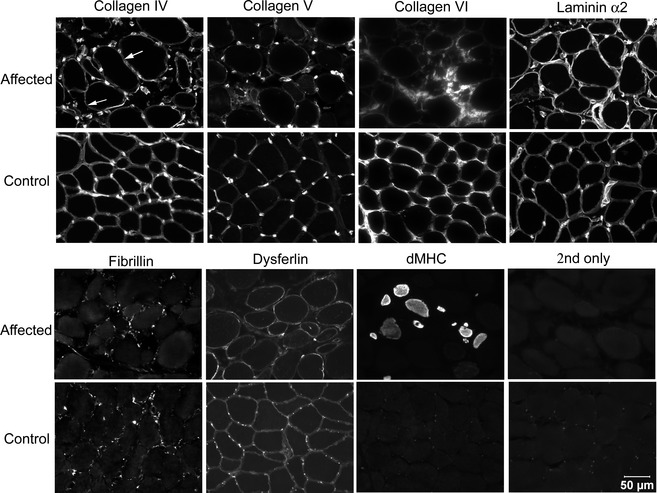

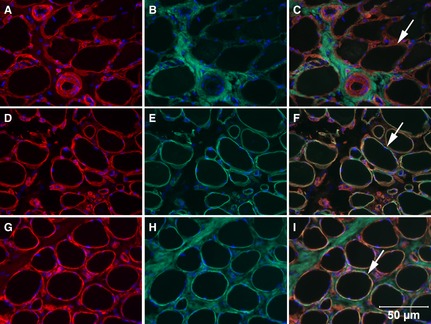

To further define this myopathy, cryosections from the biceps femoris muscle of the affected dog were incubated with monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies against collagen IV (Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody, Ab6586),2 collagen V (Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody, Ab7046),2 collagen VI (Mouse Monoclonal Antibody, 3G7),3 fibrillin (Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody, 9643),3 dysferlin (Mouse Monoclonal Antibody, NCL‐hamlet),4 spectrin (Mouse Monoclonal Antibody, NCL‐SPEC2),4 laminin α2 (Mouse Monoclonal Antibody, 1B4),3 and developmental myosin heavy chain (Mouse Monoclonal Antibody (NCL‐MHCd)4 as previously described.4 Staining for collagen IV and V, fibrillin, dysferlin, spectrin, and laminin α2 was similar to that in control tissue (Fig 3). Numerous regenerating fibers were noted in the affected canine muscle demonstrated by staining with the antibody against developmental myosin heavy chain. Staining for collagen VI was markedly decreased or absent on the sarcolemma compared to the control tissue, but was evident within the endomysium. To further assess the abnormal collagen VI staining, double staining was performed with antibodies against collagen IV (Fig 4A,D,G, to define the sarcolemma), laminin α2 (Fig 4E) to define the basal lamina, collagen VI (Fig 4B,H) and merged (Fig 4C,F,I). Cryosections from archived dystrophin deficient canine muscle were included as controls (Fig 4G,H,I). Sarcolemmal staining from the affected dog was evident with the antibody against collagen IV but not collagen VI (Fig 4C, merge red color) and with both collagen IV and laminin α2 (Fig 4f, merge yellow color). As a control, the sarcolemma from a dystrophin deficient dog stained for both collagen IV (Fig 4G) and collagen VI (Fig 4H,I, merge yellow color). These findings confirm sarcolemmal specific collagen VI deficiency in this Labrador Retriever.

Figure 3.

Cryosections from the biceps femoris muscle of the affected Labrador Retriever and archived control canine biceps femoris muscle were incubated with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against several congenital myopathy‐associated proteins including collagens IV, V and VI, laminin α2, fibrillin and dysferlin, and developmental myosin heavy chain to assess muscle regeneration. Staining for collagen VI was limited to the interstitium and muscle regeneration was noted in the affected dog. Bar = 50 μm for all images.

Figure 4.

Cryosections from the biceps femoris muscle of the Labrador Retriever with sarcolemmal‐specific collagen VI deficiency (top and middle rows) and a dystrophin‐deficient dog (bottom row) were incubated with monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies against collagen IV (A,D,G), collagen VI (B,H), laminin α2 (E), and merged (C,F,I). Absence of sarcolemmal staining with the antibody against collagen VI was evident in the dog with sarcolemmal‐specific collagen VI deficiency (C, merge, arrow points to red sarcolemmal staining for only collagen IV), but present in the sections stained for laminin α2 (F, merge, arrow points to yellow sarcolemmal staining) and from the dystrophin‐deficient muscle (I, merge, arrow points to yellow sacolemmal staining). Bar = 50 μm for all images.

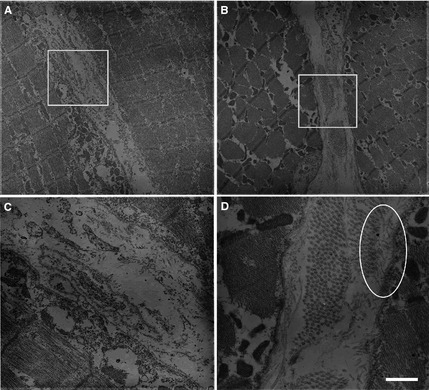

For ultrastructural analysis, previously fixed biceps femoris muscle was immersed for 2 h in 5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C, then further processed as previously described.4 Thick sections (1 μm) were cut and examined by light microscopy after staining with toluidine blue‐basic fuchsin. Ultra‐thin sections (60–65 nm) were cut and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate before electron microscopic examination. The basal lamina was intact in both the affected (Fig 5A,C) and control canine tissue (Fig 5B,D). Microfibrils were disrupted in the interstitium and not associated with the basal lamina in the affected dog (Fig 5A,C).

Figure 5.

Ultrastructural studies of the Labrador Retriever with sarcolemmal‐specific collagen VI deficiency (A,C) and control canine muscle (B,D) showed the basal lamina was intact in both affected and control muscle (arrows in C and D). Unlike normal muscle, microfibrils were disrupted in the interstitium and not associated with the basal lamina in the collagen VI deficient dog. The oval in D shows microfibrils interacting with the basal lamina in the control muscle. The areas in the boxes drawn in A and B are shown at higher power in C and D. Bar = 1.1 μm for images A and C and 0.3 μm for images B and D.

After the initial therapeutic trials with robenacoxib and prednisolone, a 4‐week therapeutic trial with cyclosporine (5 mg/kg PO q24 h) was performed. No change was noted in the dog's ability to walk or climb stairs and the medication was discontinued (Video S2 and S3). The dog was then treated with intermittent short courses of prednisolone with mild improvement in gait. Additional improvement in gait was noted after an intramuscular injection of nandrolone laurate (1 mg/kg).5 Glucocorticoid treatment was discontinued and the dog was managed with regular injections of anabolic steroids over the following 36 months. Myopathy in this case was slowly progressive with increased difficulty in climbing stairs and walking on uneven surfaces (Video S4). Because of financial limitations, it was not possible to repeat electrodiagnostic or laboratory tests after the age of 11 months. Recently, when the dog was 3 years and 10 months of age, range of motion of the dog's carpi and tarsi was measured by goniometry, as described by Jaegger et al.5 Decreased range of motion in flexion and extension was confirmed with goniometric measurements of both carpi and tarsi (Table 1); valgus and varus measurements of the carpal and tarsal joints could not be performed because of limited cooperation of the dog.

Table 1.

Goniometric measurements of joint range of motion (degrees) as described by Jaegger et al.5 The average of three measurements in the awake dog is compared to the average measurements for 16 adult healthy Labrador Retrievers

| Joint | Position | Left (Mean) | Right (Mean) | Normal (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carpus | Flexion | 80° | 78.3° | 32° ± 2° |

| Extension | 171.6° | 164.6° | 196° ± 2° | |

| Tarsus | Flexion | 91.66° | 100° | 39° ± 2° |

| Extension | 168.3° | 173.3° | 164° ± 2° |

Based on the clinical evaluation, electrodiagnostic testing, histopathology, immunostaining, and ultrastructural analysis, a noninflammatory congenital myopathy associated with sarcolemmal specific collagen VI deficiency was diagnosed. Clinical signs of collagen VI deficiency in people can vary from severe muscle weakness with axial and proximal contractures and distal joint hyperlaxity in Ullrich's congenital muscular dystrophy (UCMD) to moderate or mild muscle weakness and distal joint contractures in Bethlem myopathy (BM). Patients with UCMD might never acquire the ability to move independently or lose this ability between the first and second decade of life, concomitant with the development of frequent respiratory failure caused by the involvement of the diaphragm.6 Patients with intermediate phenotypes have a lesser degree of weakness and a longer period of ambulation than UCMD, but are more severely affected than patients with BM, the mildest form of collagen VI‐related myopathy, characterized by slowly progressive axial and proximal muscle weakness with distal joint contractures.6

The clinical presentation of a collagen VI‐related myopathy in this dog is similar to the intermediate form described in people. In the intermediate form, muscle weakness and contractures are not evident at birth, but develop during childhood and are progressive, particularly affecting ankles, knees, and elbows.6 These patients, like the dog in this report, are able to walk for limited distances particularly on flat surfaces and indoors, but require assistance with stairs and walking for longer distances.

The mild increase in CK activity (907 U/L, range 0–190) is consistent with that reported in people with collagen VI‐related myopathy (up to 5× the reference range).7 Collagen VI‐related myopathies are not associated with a muscle cell defect, but with the interstitial fibroblasts. Therefore, unlike other muscular dystrophies, serum CK activity is normal or only mildly increased even in the severe form of UCMD.6

There are only a few publications with detailed electrodiagnostic data concerning congenital muscle dystrophies, such as collagen VI‐related myopathies in humans.8 Recently, a retrospective study with data on EMG and nerve conduction studies in children affected by congenital muscle dystrophy has been published.8 Only three of the 26 children examined in this study had a collagen VI‐related myopathy (UCMD) and two of these children had low‐borderline motor and sensory NCV at 2 years of age. The authors did not propose an explanation for these findings.8 A similar delay in motor nerve conduction velocity was also found in this dog and peripheral nerve involvement cannot be ruled out.

Lesions in the muscle biopsies were myopathic but relatively nonspecific consisting of excessive variability in myofiber size, atrophic fibers having a round shape and of both fiber types, small numbers of myofibers containing internal nuclei, endomysial fibrosis, mild to moderate mononuclear cell infiltrations, and subsarcolemmal accumulations of NADH‐TR positive material. Similar relatively nonspecific myopathic changes are described in human patients with collagen VI deficiency.9

In skeletal muscle, collagen VI is normally located within the extracellular matrix and strongly delineates the sarcolemma. Collagen VI is thought to anchor the basement membrane in skeletal muscle by interacting with collagen IV, a major component of the basal lamina.10 In patients with collagen VI deficiency, collagen VI is deficient either completely, which is referred to as complete deficiency, or only absent from the sarcolemma, which is called sarcolemma‐specific collagen VI deficiency (SSCD).11, 12 In patients with SSCD, collagen VI is present by immunostaining in the interstitium but specifically absent in the sarcolemma. As shown in this case report by double immunostaining (Fig 4), labeling of collagen IV was present on the sarcolemma whereas staining for collagen VI was present within the interstitium but not on the sarcolemma. By electron microscopy, the basal lamina was intact and microfibrils were present in the interstitium, but were not associated with the basal lamina as evident in control muscle (Fig 5). Such ultrastructural findings were also observed in human SSCD patients.11

Mutations in the three collagen VI genes COL6A1, COL6A2, and COL6A3, have been associated with collagen VI deficiency in both the severe UCMD and the milder BM.6 Mutations in both COL6A1 and COL6A2 have been identified in some patients with SSCD; however, other patients lack mutations in collagen VI genes and a failure to anchor the basal lamina to the intersititum, possible because of mutations in other molecules has been postulated.12, 13 Identifying the underlying mutation responsible for the collagen VI deficient myopathy affecting the dog in this case report will be important for diagnostic and research purposes and it is the planned next step in the investigation of this condition.

Unfortunately, a pedigree or information on related dogs was not available. Identification of similarly affected dogs could be of considerable value for comparative studies. Currently, mouse and zebrafish models are available. The mouse model was generated by knockout of the collagen VI COL6A1 locus resulting in complete absence of collagen VI expression. Although the muscles were histologically abnormal, there was a very mild clinical phenotype.14 The mouse model has led to significant discoveries in the pathogenesis of collagen VI‐related myopathies. More recently, zebrafish models of both UCMD and BM were created with morpholino antisense technology, and may be particularly useful for whole‐organism screens for pharmacologic treatments.15, 16

Modification in the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, either pharmacologically with cyclosporine A (CsA) or genetically, by knockout of cyclophilin D, improves the mitochondrial changes and reduces myofiber cell death in collagen VI‐related myopathies.17, 18 A long‐term evaluation of CsA treatment in 6 children treated for 1–3 years with maintenance doses of CsA between 1.25 and 3 mg/kg q24 h showed a significant increase in muscle strength without changes in muscle function or effects on the progressive deterioration of respiratory function.17 The efficacy of CsA in this dog could not be evaluated owing to the limited duration of the treatment and lack of objective measurements in muscle strength. An improvement in muscle weakness was noted after the administration of nandrolone, it is possible that the response to this anabolic steroid might be a placebo effect, as previously reported in veterinary medicine.19 However, oxandrolone, a synthetic anabolic steroid, appeared to slow or stabilize the progression of muscle weakness in the early stages of DMD.20

We report a collagen VI‐associated myopathy in dogs. Although a specific mutation in collagen VI has not yet been identified, results of immunostaining and ultrastructural analysis are consistent with the diagnosis of SSCD. The findings in this study also expand the spectrum of naturally occurring congenital myopathies in dogs.21 The diagnosis of this condition in the early stages of disease could pose some significant challenges owing to the slow progression of the clinical signs, presence of joint contractures and skeletal deformities, and nonspecific muscle histology. This case should alert clinicians to the possibility of an underlying congenital myopathy in dogs presenting with skeletal deformities and joint contractures.

Supporting information

Video S1. Female spayed Labrador retriever with collagen VI‐related myopathy. Gait at 11 months of age.

Videos S2 and S3. Female spayed Labrador retriever with collagen VI‐related myopathy. Ascending stairs at 18 months of age, before (S2) and after (S3) a 4‐week cyclosporine trial.

Video S4. Female spayed Labrador retriever with collagen VI‐related myopathy. Gait at 38 months of age.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Tanya Miller BSc (Hons), RVN, CCRP, for her assistance with the goniometric measurements.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors disclose no conflict of interest

Footnotes

Laboklin (UK), Manchester, UK

Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA

Gift of Dr Eva Engvall, Sanford Burnham Medical Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA

Novocastra, Leica Biosystems, Bannockburn, IL, USA

Laurabolin; MSD Animal Health, Milton Keynes Buckinghamshire, UK

References

- 1. Pele M, Tiret L, Kessler J‐L, et al. SINE exonic insertion in the PTPLA gene leads to multiple splicing defects and segregates with the autosomal recessive centronuclear myopathy in dogs. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:1417–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee AF, Bowen JM. Evaluation of motor nerve conduction velocity in the dog. Am J Vet Res 1970;31:1361–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dubowitz V, Sewry CA. Histological and histochemical stains and reactions In: Dubowitz V, Sewry CA, ed. Muscle Biopsy: A Practical Approach, 3rd ed London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:21–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zi‐Fang L, Wu X, Jiang Y, et al. Non‐pathogenic protein aggregates in skeletal muscle in MLF1 transgenic mice. J Neurol Sci 2008;264:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaegger G, Marcellin‐Little DJ, Levine D. Reliability of goniometry in Labrador Retrievers. Am J Vet Res 2002;63:979–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bönneman CG. The collagen VI‐related myopathies: Muscle meets its matrix. Nat Rev Neurol 2011;7:379–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Voit T, Tome FM. The congenital muscular dystrophies In: Engel AG, Franzini‐Armstrong C, eds. Myology, Basic and Clinical, 3rd ed New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 2004:1230. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quijano‐Roy S, Renault F, Romero N, et al. EMG and nerve conduction studies in children with congenital muscle dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 2004;29:292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dubowitz V, Sewry CA. Congenital myopathies In: Dubowitz V, Sewry CA, ed. Muscle Biopsy: A Practical Approach, 3rd ed London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:407–442. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuo HJ, Maslen CL, Keene DR, et al. Type VI collagen anchors endothelial basement membranes by interacting with type IV collagen. J Biol Chem 1997;272:26522–26529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ishikawa H, Sugie K, Murayama K, et al. Ullrich disease: Collagen VI deficiency: EM suggests a new basis for muscular weakness. Neurology 2002;59:920–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ishikawa H, Sugie K, Murayama K, et al. Ullrich disease due to deficiency of collagen VI in the sarcolemma. Neurology 2004;62:620–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawahara G, Okada M, Morone N, et al. Reduced cell anchorage may cause sarcolemma‐specific collagen VI deficiency in Ullrich disease. Neurology 2007;69:1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bonaldo P, Braghetta P, Zanetti M, et al. Collagen VI deficiency induces early onset myopathy in the mouse: An animal model for Bethlem myopathy. Hum Mol Genet 1998;7:2135–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allamand V, Briñas L, Richard P, et al. ColVI myopathies: Where do we stand, where do we go? Skelet Muscle 2011;1:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Telfer WR, Busta AS, Bonnemann CG, et al. Zebrafish models of collagen VI‐related myopathies. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:2433–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merlini L, Angelin A, Tiepolo T, et al. Cyclosporin A corrects mitochondrial dysfunction and muscle apoptosis in patients with collagen VI myopathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:5225–5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merlini L, Sabatelli P, Armaroli A, et al. Cyclosporine A in Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy: Long‐term results. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2011;2011:139194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muñana KR, Zhang D, Patterson EE. Placebo effect in canine epilepsy trials. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fenichel GM, Griggs RC, Kissel J, et al. A randomized efficacy and safety trial of oxandrolone in the treatment of Duchenne dystrophy. Neurology 2001;56:1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shelton GD, Engvall E. Canine and feline models of human inherited muscle diseases. Neuromuscul Disord 2005;15:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1. Female spayed Labrador retriever with collagen VI‐related myopathy. Gait at 11 months of age.

Videos S2 and S3. Female spayed Labrador retriever with collagen VI‐related myopathy. Ascending stairs at 18 months of age, before (S2) and after (S3) a 4‐week cyclosporine trial.

Video S4. Female spayed Labrador retriever with collagen VI‐related myopathy. Gait at 38 months of age.