Abstract

Background

Kidney disease (KD) is common in older cats and presumed to arise from subclinical kidney injuries throughout life. Sensitive markers for detecting kidney injury are lacking. Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM‐1) is a useful biomarker of kidney injury in humans and rodents.

Hypothesis/Objectives

Feline KIM‐1 is conserved across species, expressed in kidney, and shed into urine of cats with acute kidney injury (AKI). The objectives were to characterize the feline KIM‐1 gene and protein, assess available immunoassays for detecting KIM‐1 in urine of cats, and identify KIM‐1 expression in kidney sections.

Animals

Samples from 36 hospitalized and 7 clinically healthy cats were evaluated. Hospitalized cats were divided into 2 groups based on absence (n = 20) or presence (n = 16) of historical KD.

Methods

Feline KIM‐1 genomic and complementary DNA sequences were amplified, sequenced and analyzed to determine the presence of isoforms, exon‐intron organization and similarity with orthologous sequences. Presence in urine was evaluated by immunoassay and expression in kidney by immunohistochemistry.

Results

Three expressed feline KIM‐1 transcript variants comprising 894, 810, and 705 bp were identified in renal tissue. KIM‐1 immunoassays yielded positive results in urine of cats with conditions associated with AKI, but not chronic KD. Immunohistochemistry of kidney sections identified KIM‐1 in proximal tubular cells of cats with positive urine immunoassay results.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Kidney injury molecule 1 was expressed in specific segments of the nephron and detected in urine of cats at risk of AKI. Urine KIM‐1 immunoassay may be a useful indicator of tubular injury.

Keywords: Feline, Renal disease, Serum creatinine, Urinalysis

Abbreviations

- AA

amino acid

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- bp

base pair

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CBC

complete blood count

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- KD

kidney disease

- KIM‐1

kidney injury molecule 1

- NAG

N‐acetyl‐beta‐D‐glucosaminidase

- OSOM

outer stripe of the outer medulla

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RI

reference interval

- SC

serum creatinine

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- UA

urinalysis

- UIA

urine immunoassay

- USG

urine specific gravity

Chronic kidney disease (KD) is a common condition of unknown etiology in older cats. Chronic KD has been defined as structural or functional impairment of 1 or both kidneys for longer than 3 months.1 Surveys have shown an incidence of 15.3% in cats >15 years of age, and more recently of 27.2% in cats >10 years of age.2, 3 In another study, during 1 year of observation, KD developed in 30.5% of clinically healthy cats >9 years of age.4 Thus, KD is very common in older cats. Although some causes of KD such as urethral obstruction and ethylene glycol or lily toxicity are well known, in many cases the cause of KD is unknown and may be multifactorial.5 Progression of chronic KD in cats may be clinically inapparent or very gradual.

In human medicine, acute kidney injury (AKI) has replaced the term acute renal failure. AKI has been proposed to encompass the entire spectrum from minor change in renal function to requirement for renal replacement treatment.6 Thus, the change in terminology is meant to imply that acute injury may progress to chronic KD or may result in recovery. In humans, AKI most often occurs concurrent with other disease, and risk factors for AKI are ill defined but even transient azotemia is associated with increased mortality.7, 8 AKI Network (AKIN) criteria define AKI as a reduction in kidney function over 48 hours associated with an absolute increase of ≥26.4 μmol/L (≥0.3 mg/dL) or a percentage increase of ≥50% (1.5‐fold from baseline) in serum creatinine (SC) concentration, or a decrease in urine output.6 Thus, by these criteria, relative increases in SC may be small and remain within the SC reference interval (RI) (termed “critical difference”), but nevertheless indicate AKI.

Acute kidney injury is identified infrequently in cats, which may be because of limitations of current diagnostic approaches or because of the subclinical nature of many kidney injuries in cats. Reviews of AKI in cats have addressed causes of clinical signs of KD, but understanding of the causes of subclinical injury remains incomplete.9 It is plausible that in cats, as in people, episodic subclinical injury or clinical AKI with apparent recovery can progress to chronic KD.10, 11, 12 However, ability to diagnose and prognosticate AKI in cats is very limited. Serum creatinine concentration is the most widely used biomarker for KD, but is an insensitive and imperfectly specific indicator because azotemia develops only after approximately 75% reduction in renal function.13 A range of other potential biomarkers has been assessed in cats, but to date none has predicted progression of renal disease better than SC concentration.4, 14, 15 In cats and people, SC concentration varies among individuals, and critical differences within the same individual rather than relative to a population without KD may be more meaningful.16, 17, 18 Recently, approaches for the diagnosis of AKI in cats and dogs similar to AKIN criteria in people have been proposed.19, 20, 21, 22 These approaches incorporate a range of clinical and laboratory variables, but limitations because of lack of sensitive indicators of AKI remain.

Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM‐1), also known as hepatitis A virus cell receptor 1 (HAVCR1) and T cell immunoglobulin 1, is a renal tubular transmembrane glycoprotein thought to function in cell‐to‐cell or cell‐to‐matrix adhesion.23, 24 KIM‐1 has characteristics that make it a useful biomarker for AKI in people and rodents: low expression in healthy kidneys, rapid 3‐ to 100‐fold increase after ischemic or toxic injury and release of an extracellular portion into urine.23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Urine KIM‐1 concentration correlated with severity of AKI and decreased as kidney repair progressed.27 For these reasons, KIM‐1 also maybe a useful marker of AKI in cats. Hence, the goals of this study were to identify and characterize feline KIM‐1 and to investigate expression and measurement in health and disease.

Materials and Methods

Sequence Data Sources

The following KIM‐1 nucleotide and amino acid sequences were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database: Homo sapiens, NP_036338.2; Canis lupus, NP_001192043.1; Mus musculus, NP_599009.2; Rattus norvegicus, NP_775172.1; and Pan troglodytes, XP_001135569.1 (all accessed January 2014). Felis catus genomic sequence was obtained from the Genome Annotation Resource Fields (GARFIELD) feline database.28, 29 Multiple sequence alignments were performed with Geneious Pro software1 to identify areas of similarity, which were then further investigated using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and Constraint‐Based Multiple Alignment Tool (COBALT) provided by NCBI. Conserved regions of KIM‐1 were selected for primer design.

Amplification of Feline KIM‐1 cDNA

Fresh feline kidney tissue was obtained from a cat euthanized for causes unrelated to this study, immersed in RNAlater2 and frozen at −80°C. RNA purification was performed using the RNeasy Mini Kit2 according to the manufacturer's protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized with Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase.3 KIM‐1 cDNA variants including complete open reading frames were amplified by PCR with KIM‐1 forward (5′‐GGC ACA CCT ACC AGT CTG CTT‐3′) and KIM‐1 reverse (5′‐CTG TCT TCT GCA GTC AAG GG‐3′) primers.4 Polymerase chain reaction amplifications were carried out with HotStarTaq Plus DNA polymerase in a final volume of 20 μL, including 10 μL of 2× HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix PCR buffer, 0.2 mM MgSO4, 0.5 μM of each primer, and 2 μL of template DNA. Conditions for amplification were 1 minute at 94° followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds; 57°C for 30 seconds; and 72°C for 90 seconds with a final extension at 72° for 7 minutes. Polymerase chain reaction products were separated by electrophoresis and bands of appropriate size were excised from the gel, purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit,2 and submitted for automated sequencing.5

Characterization of the Feline KIM‐1 Gene

The feline cDNA sequence was aligned with the canine KIM‐1 genomic sequence (GenBank AAEX03003064.1) to predict exon‐intron boundaries. Multiple potential exons in the cDNA were identified, and a strategy was designed to sequentially amplify all introns and exons with specific primers (Table 1) and to generate a contiguous consensus sequence. Optimized conditions for amplification were 5 minutes at 94°C followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds; 58°C for 30 seconds; and 72°C for 3 minutes with a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. Polymerase chain reaction products were isolated by electrophoresis, purified and sequenced. Based on analysis of sequences obtained, additional primers were designed as needed to complete amplification of the entire gene. Individual overlapping sequences were assembled with Geneious Pro software.

Table 1.

Primer sequences (5′–3′) for sequential amplification of the feline kidney injury molecule 1 gene.

| Primer | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | GAACACAGCGGGTGGTTCAAT | CGTGGGTGCTGGCATTGAAG |

| 2 | CTCCAGTGCAGACAGCAGAAA | ATCTGAAGACTGTGTCACAGT |

| 3 | ATGGATGACCACCAGTAAGGG | GTTCCAGCTTGTTTCTTACGC |

| 4 | GCGTAAGAAACAAGCTGGAAC | CGCTGGGTCTTAATCCATGAC |

| 5 | ACTTGTTCCGAGACCATCTGG | TGACTTTGGGAAATGCTCTCTGG |

| 6 | GAATCCCAAGCAGGCTCCACT | CCAAAGAGTCAACATCTCAGC |

| 7 | GTTGCATTGGTACATGGGCCC | TAACCTTGTGGCCTGAATGAG |

| 8 | GTAGCATGGGCACTGATTGAC | TGTAAAGGATCACCACCTCCT |

| 9 | GGGATCTCTTTAGGATTTGAG | CTTGCACTGTGTTCCCTTAGG |

| 10 | GCCAAACTGCCTGAGTTCGAG | GGCTTAGTGTATTCACCCACA |

| 11 | CAGGCTCAGCTCTGTCCAGG | CTCCTTCTGTAGCAGTTCTGG |

| 12 | GTGGACAGAAACACATCAGC | GAGTCAGTGTGATGAGAACTG |

| 13 | GGCAGAAAAGCATGGAACAC | GCCTACCATCATAACTGAC |

| 14 | CATTCACTACCAGAAGGCAACGTG | GCATCAGGAGTATTTAGGGCCCC |

| 15 | GCTTGCTTAAGCGTATCCTCCTTC | CCAGCATAGGCCTGGCTATATACC |

| 16 | CTGCATGCACTCATGTGCACTCTCT | GCTCAGTCAGTTATGCGTCTGACTC |

| 17 | GCCCATGATAAACCTCAGCTCCTCC | GAGAGGTGCTGTGAGGGGACATCA |

| 18 | AAGTGTCCGGCTTCAGCTCAGGT | ATTGGAGGCAGAGTCACCTTGGC |

| 19 | GCATTTACAAGGGCAGTGCCCTGTC | CGGAATTAAGCCCCAACAAGGACTG |

| 20 | CCCTGTCTTCTCTAGGCATTC | CCTGAGGAGGTCACATGGACATATG |

| 22 | CAGCTCTGTTTGAGGCAGCTG | GGACAAGAATTCCCAAACCTGGG |

| 23 | GAAATGTGGAGATCACTGTGGGG | CAACAGCACCTTATGTAGGACATCC |

| 24 | GGGCAAATAAGCACAAACCCC | CAGGTCAGGTCTGTCTTACTCCG |

| 25 | TTCTGGAGAGTGCCACACGCTAA | CCAGGTCACGATCTCGTCGTCTGT |

| 26 | ACAGAGAGAGACAGAACATGAACGG | CGTGGAAGATTGTGTGCCTTAACC |

| 27 | GCCTGAGTTCGAGTAGCTCCACA | CTGTGGCTCTTTCATAGAAGGAAGG |

| 28 | CCCCATGCAAGGCATAAAACA | GAGTTACGAGTAGAAGACATTCCC |

| 29 | GGGAAGTTGATCGTGATTCCTGA | TCAGGAATCACGATCAACTTCCC |

| 30 | GGTTTGGTTGTATGGTTTGAAGCTG | GGAGGTAACCTGATGGAATTGTC |

| 31 | ACTGAGGTAGGTAGATGCCCC | TTGGGGCATCTACCTACCT |

Urine Samples and KIM‐1 Immunoassay

Aliquots of urine remaining after urinalysis was performed6 were collected. Samples from cats in the intensive care unit (ICU) of the Ontario Veterinary College Health Sciences Complex with concurrent complete blood cell count (CBC) and serum biochemical results were selected. Samples were voided into nonabsorbent litter or collected by catheter or cystocentesis, as indicated by attending clinicians. Where possible, subsequent urine samples also were collected. Urinalyses were performed using an automated urine dipstick reader and semiquantitative microscopic sediment analysis. All serum assays were performed on a Cobas 4800 biochemistry analyzer.7 Urine cultures were requested at the discretion of clinicians. Cases were categorized as critically ill with no history of KD (group A) or critically ill with history of KD (group B). Assignment of previous KD was based on historical laboratory results indicating SC concentration above RI and urine specific gravity (USG) < 1.035 over a period of >1 month. Samples from cats with equivocal history or incomplete laboratory results were excluded. Urine and blood samples collected from nonhospitalized cats without illnesses were analyzed as above (approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee, protocol 10R030). These cats (group C) had CBC and biochemical results within laboratory RI and USG > 1.035. All urine samples were stored in plastic tubes without additives at 4°C for up to 24 hours before freezing at −80°C. KIM‐1 in urine was detected with a lateral flow device designed to detect rat KIM‐18 according to the manufacturer's instructions with color reactions read at 20 minutes. This point‐of‐care assay utilizes gold nanoparticles impregnated with KIM‐1 antibody on a multilayer membrane with capillary action. Results were classified as “positive” or “negative” according to presence or absence of a color reaction in the test sample and if the positive control reaction yielded a color reaction.

KIM‐1 Immunohistochemistry

Expression of KIM‐1 in kidney tissues was investigated by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Five‐micrometer‐thick, paraffin‐embedded sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohols, incubated consecutively for 10 minutes with dual endogenous enzyme blocker, 30 minutes with serum‐free protein blocker, overnight with an optimized dilution of antibody to KIM‐1 human MAb Clone 2192119 and 30 minutes with Envision Dual Link System‐HRP.10 Bound antibodies were detected with Nova Red chromogen,11 and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Each batch of slides included negative (omission of primary antibody or preincubation of antibody with human KIM‐1 peptide for 2 hours at dilution of 1 : 40) and positive controls (sections from a cat with acute tubular necrosis). KIM‐1 immunohistochemical staining was assessed as positive or negative.

Results

Characterization of the Feline KIM‐1 cDNA and Gene

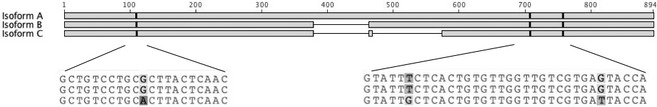

The feline genome database GARFIELD was searched using the key words KIM‐1 and HAVCR1.28, 29 Chromosome A1 contained 4 coding regions with similarity to HAVCR1 that were imported into Geneious Pro software. Regions were aligned with HAVCR1/KIM‐1 sequences of rat, dog, mouse, and human using BLAST and COBALT. A region highly similar to KIM‐1 of other species was identified in 1 of the feline sequences. Sequential application of primers that encompassed start and stop codons to kidney cDNA yielded 3 amplicons termed isoforms A, B, and C, which corresponded to 894, 810, and 705 bp, respectively (Fig 1). Three polymorphic nucleotides differentiated isoform C from A and B. Overall identity was 90.6% for isoforms A and B, and 78.5% for isoforms A and C. Sequences were deposited in NCBI GenBank with accession numbers KF540032, KF540033, and KF540034.

Figure 1.

The full‐length feline kidney injury molecule 1 cDNA isoform (A) consists of 894 bp. Two shorter isoforms (B and C) of the gene are also expressed in adult kidney tissues, and consist of 810 and 705 bp, respectively. There are 3 polymorphic sites that distinguish isoform C from A and B.

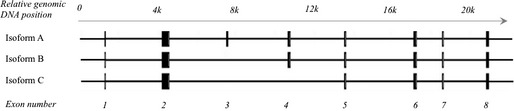

Eight exons were predicted by alignment of feline cDNA sequences with canine KIM‐1 genomic DNA. To amplify the entire feline KIM‐1 gene, a first set of primers was based on a related canine genomic sequence, and subsequent primers (Table 1) were designed sequentially to match newly derived sequences until the entire gene sequence of 21,059 bp was determined. Alignment of the feline cDNA sequence with the full feline genomic DNA sequence indicated 8 exons in isoform A, 7 in isoform B, and 6 in isoform C (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram showing the feline kidney injury molecule 1 gene. Eight identified exons are represented as black boxes and spread over 21,059 bp of genomic DNA. A total of 3 expressed variants were identified in renal tissues consisting of 8 (isoform A), 7 (isoform B), and 6 (isoform C) exons, respectively.

Functional Motifs of Feline KIM‐1

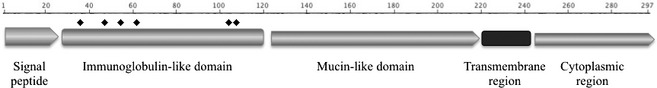

In silico translation of the full‐length feline cDNA yielded a protein of 297 amino acids (AA). Analysis of this sequence for conserved domains using tools of the NCBI Conserved Domains Database indicated presence of an immunoglobulin (Ig)‐like domain with 6 cysteines, a mucin‐like domain rich in threonines, serines, and prolines, a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic domain containing a conserved tyrosine motif (Fig 3).30 Similar motifs are present in rat and human KIM‐1 proteins. Presence of 14 asparagines with specific adjacent AA in the cytoplasmic domain indicated 4 possible glycosylation recognition sites. Absence of exon 3 in isoform B, and exons 3 and 4 in isoform C, results in progressive loss of the mucin‐like domain such that isoform C contains few threonines, serines, and prolines. In isoform C, alanine at position 37 is replaced by threonine, phenylalanine at position 237 by leucine, and serine at position 245 by isoleucine. Thus, isoform C differs at 3 positions from isoform A and B.

Figure 3.

Schematic of predicted functional domains of the feline kidney injury molecule 1. Cysteine = ♦.

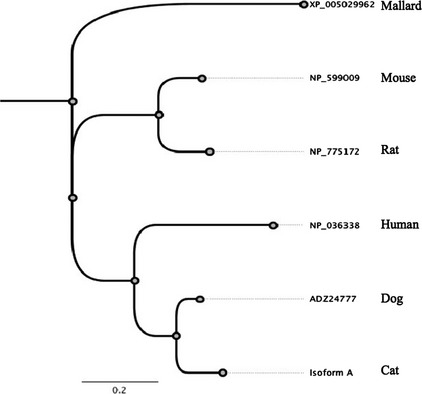

Phylogenetic Analysis

Amino acid alignment (Geneious Pro, blocks substitution matrix = 65, gap open penalty = 12, gap extension penalty = 3, free end gap setting) of KIM‐1 isoform A with the corresponding dog, human, mouse, and rat sequences (GenBank ADZ24777, NP_036338, NM_599009, and NM_775172, respectively, accessed January 28, 2014) indicated 83.2%, 43.8%, 44.7%, and 43.7% identity, respectively. Calculation of phylogenetic relationships (Geneious Pro, Jukes Cantor model, neighbor‐joining method) with the mallard (Anas platyrhynochos) KIM‐1 sequence (GenBank XP_005029962) as an outlier confirmed the closest relationship of feline KIM‐1 with canine KIM‐1 and a relatively greater distance to horse, human, and rodent sequences (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of kidney injury molecule 1 amino acid sequences from different species. Note feline and canine sequences are most closely related.

Urine Samples

Urine samples were available from 36 ill and 7 clinically healthy cats. Of the ill cats, 20 had no evidence of KD before admission (group A) and ranged in age from 1 to 17 years (mean, 6.5 years; Tables 2, S1). These cats had a variety of critical illnesses with the potential to cause AKI. First biochemical evaluation in ICU indicated SC concentration above RI in 4 cats (RI, 50–190 μmol/L; 0.57–2.15 mg/dL). In 15 cats, USG was <1.035, which was likely attributable to fluid administration because urine samples were inconsistently collected before initiation of treatment.

Table 2.

Signalment, clinicopathologic data, and KIM‐1 immunotesting results.

| Group | Age (years) | SCC (μmol/L) | USG | Urinalysis | KIM‐1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinuriaa | Hematuriaa | WBC | UIA | IHC | ||||

| A – critical illness, no previous KD (n = 20) | 6.5 ± 3.5 | 297 ± 452 | 1.023 ± 0.018 | 17/20 | 16/20 | 4/20 | 7/20 | 4/4 |

| B – critical illness, previous KD (n = 16) | 9.4 ± 4.6 | 427 ± 371 | 1.015 ± 0.007 | 12/16 | 9/16 | 4/16 | 4/16 | 3/6 |

| C – healthy (n = 7) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 97 ± 17 | 1.048 ± 0.008 | 7/7 | 1/7 | 1/7 | 1/7 | ND |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

SCC, serum creatinine concentration; USG, urine specific gravity; WBC, urine sediment 3–5 WBC/40× field; UIA, positive KIM‐1 urine immunoassay results; IHC, positive KIM‐1 immunohistochemical stain in kidney sections; ND, not done.

Urine dipstick 1+ to 3+ reaction.

Sixteen ill cats had historical KD (group B) as indicated by persistently increased SC concentration and USG < 1.035, and ranged in age from 0.5 to 17.0 years (mean 9.4 years). Initial laboratory results during hospitalization identified SC concentrations >100 μmol/L above historical values in 8 cats, which was ascribed to recent AKI superimposed on chronic KD. Five cats had SC concentration within RI upon admission but had received fluid therapy before referral or had developed hyperthyroidism in addition to KD. In this group of 16 cats, SC concentration ranged from 85 to 1238 μmol/L (0.96–14.00 mg/dL; Table 2).

Seven clinically healthy cats had no history of KD and ranged in age from 1 to 3 years. Three were neutered males, 3 were intact males, and 1 was an intact female. SC concentration ranged from 49 to 125 μmol/L (0.55–1.41 mg/dL). USG on admission ranged from 1.039 to 1.064, urine protein dipstick reactions ranged from 1 to 3 (approximately 0.3–4 g/dL), all samples were negative for urine glucose, and hemoglobin dipstick reactions ranged from 0 and 2 (none to approximately 0.020 mg/dL).

Urine KIM‐1 Immunoassay

The urine immunoassay (UIA) test completion required approximately 20 minutes, and test positive controls consistently yielded the expected reaction (Fig 5). Eight positive UIA results were obtained from 7 cats of group A (critically ill, no previous KD). Two cats had SC concentrations that increased during hospitalization but remained within RI, conditions potentially associated with hypoperfusion (severe pancreatitis and advanced myocardial disease, respectively) and positive UIA results after initial negative UIA results. Four cats had SC concentration within RI but positive UIA results on admission, and 2 of these were retested within a few days and negative UIA results were obtained. One cat had increased SC concentration because of urethral obstruction lasting several days and 2 consecutive positive UIA results. After a few days, a repeated UIA result was negative and SC concentration was within RI.

Figure 5.

R‐Renastick kidney injury molecule 1 urine immunoassay. Positive control reactions on left, test sample reactions on right. (A) Test results from a cat that developed acute kidney injury during hospitalization. Initial test result was negative (top) and the subsequent test result was positive. (B) Test results from a cat with acutely exacerbated chronic kidney disease. Initial test results were positive and then became negative.

Thirteen cats of group A had negative KIM‐1 UIA results on admission. Four of these 13 cats were euthanized in hospital because of untreatable underlying conditions and 1 died at home 6 days after discharge. Two of the 13 cats had ingested lilies 4 or more days before referral.

Results of UIA were positive on admission in 4 of 16 cats of group B (critically ill, prior KD). Two of these 4 cats had terminal cancer, 1 had hyperthyroidism, and 1 had unresponsive acute exacerbation of chronic KD. Two cats had subsequent negative UIA results concurrent with decreased SC concentrations. Twelve cats of group 2 had single or multiple negative UIA results. Samples from all cats of group C yielded negative UIA results.

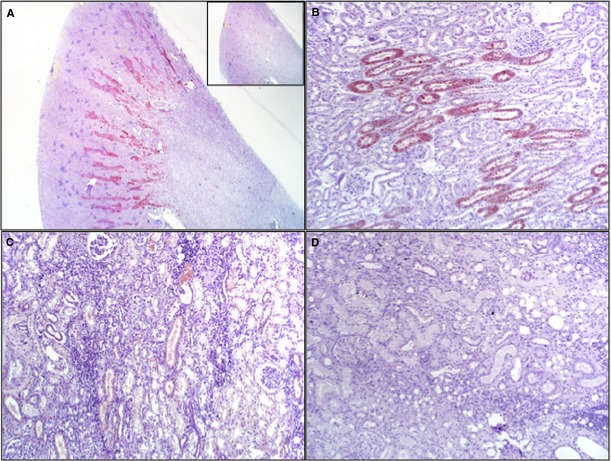

KIM‐1 Immunohistochemistry

Kidney sections were evaluated from all cats submitted for postmortem examination or from biopsies obtained antemortem. Thus, wedge kidney sections including cortex and medulla were available from 4 cats of group A and 5 cats of group B. From 2 additional cats of group B, biopsies comprised only of cortex were available. Sections from group A cats had variably severe acute tubular necrosis but no evidence of chronic KD (eg, fibrosis, glomerular sclerosis, and inflammatory cells).31 KIM‐1 IHC staining consistently was detected in proximal convoluted tubules from cats with acute tubular necrosis, and staining was abrogated by preincubation of the antibody with KIM‐1 peptide or omission of antibody (Fig 6A). KIM‐1 staining was considered to be specific because of lack of staining in sections in which antibody was preincubated with KIM‐1 peptide, and absence of KIM‐1 staining of glomeruli, endothelium, and medullary regions (Fig 6A). Staining in sections from cats of group A typically was prominent in individual tubules of the outer stripe of the outer medulla (OSOM), and also noticeable in luminal cell debris (Fig 6B). The OSOM contains the distal segment of the straight portion of the proximal tubule, the collecting ducts, and descending portion of the loop of Henle located near the cortico‐medullary junction.32

Figure 6.

Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM‐1) immunohistochemical staining of sections from cats with various kidney diseases. (A) Cat with hypoperfusion, no prior kidney disease, positive KIM‐1 urine, note tubular staining in the OSOM. Inset: Preincubation of antibody with KIM‐1 peptide abrogates staining (12.5× magnification). (B) Cat with acute kidney injury because of bite wounds, sepsis and hypotension, positive urine KIM‐1 result. Note staining of individual tubules. (C) Cat with acute exacerbation of chronic renal disease. Renal fibrosis and tubular necrosis were present at postmortem. Urine KIM‐1 result was positive on admission. There is sparse KIM‐1 staining in individual proximal tubular cells and lumen. (D) Cat with glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis because of chronic urolithiasis, negative urine KIM‐1 result. Note absence of KIM‐1 staining (1,000× magnification).

Sections from cats of group B had evidence of chronic KD such as multifocal fibrosis, interstitial nephritis, glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, or some combination of these. KIM‐1 staining in sections from 3 cats with positive UIA results was variably intense and confined to occasional tubules of the OSOM and luminal cell debris (Fig 6C). Sections from 1 cat with multiple negative UIA results, chronic KD, severe fibrosis, and interstitial inflammation had no tubular staining for KIM‐1 (Fig 6D). Biopsy sections also showed no KIM‐1 immunostaining, but these sections lacked the OSOM.

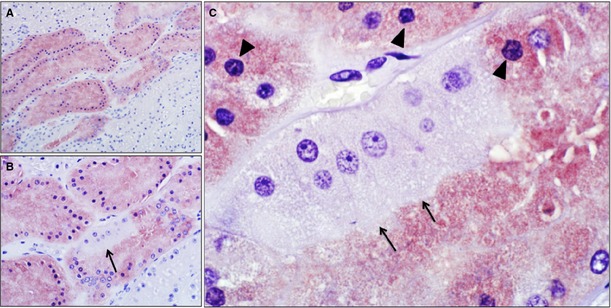

At high magnification, tubules from cats with AKI because of potential hypoperfusion and ischemia showed variable staining, with absence of KIM‐1 staining in intact cells with brush borders suggestive of proximal tubular cells, and moderately intense staining in cells with pyknotic nuclei (Fig 7).

Figure 7.

Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM‐1) immunohistochemical staining of a kidney section (medullary ray) from a cat with an episode of likely hypoperfusion; NovaRed substrate and hematoxylin counterstain. (A) Note variable staining among tubules (200× magnification). (B) There is also variable staining among epithelial cells within a tubule (arrow, 400× magnification). (C) Note KIM‐1 negative tubular epithelial cells with intact brush border (arrows) indicating proximal tubule. Adjacent KIM‐1‐positive cells have indistinct brush borders and pyknotic nuclei (arrowhead) suggesting injury (1,000× magnification).

Discussion

Urine KIM‐1 is a promising biomarker of kidney injury and KD in humans. Kidney disease is very common in cats, but sensitive, specific and noninvasive biomarkers of KD or injury are lacking. Hence, goals of this study were to characterize the feline KIM‐1 gene and protein, and to assess the utility of available KIM‐1 assays in cats at risk of kidney injury and in those with naturally occurring KD.

Feline KIM‐1 cDNA amplified from kidney tissue of cats had similar structure to that of human, rat, mouse, and dog, and contained a cytoplasmic motif highly conserved across species. Analogous to dogs, cats have 3 isoforms of feline KIM‐1 cDNA, whereas mice have 2 isoforms, and humans and rats have only 1.23, 24, 33, 34 Functions of the different isoforms have not been determined, but exon‐intron structure of cDNA predicted from genomic KIM‐1 sequences suggests derivation from alternative splicing. Exon deletion appears to be the most common mechanism that gives rise to such isoforms.35 Because KIM‐1 also may be expressed by lymphocytes, which can be present in kidney tissue, it is conceivable that there may be cell‐ and tissue‐specific expression and unique functions of different isoforms.36 Furthermore, KIM‐1 isoforms could be expressed differentially in specific regions of the nephron or in response to different types of injury. Nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in isoform C result in 3 AA changes, and 2 of these AA have different biochemical properties, suggesting that this isoform may have subtle functional differences. Single nucleotide polymorphisms have not been investigated regarding population frequency or breed association.

Conservation of certain KIM‐1 motifs across multiple species suggests similar functions. The extracellular Ig‐like domain likely mediates protein‐protein interactions at the cell surface, and cell‐extracellular matrix adhesion.37 The cysteine sites allow folding of the Ig‐like domain to form recognition sites for ligands such as phosphatidylserine expressed on apoptotic cells.38 The mucin‐like domain in full‐length KIM‐1 is likely responsible for cell‐to‐cell adhesion.24 Absence of a section of the mucin‐like domain in isoform C suggests this isoform may have lost cell‐cell adhesive function. A highly conserved cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase phosphorylation motif with expected function in signal transduction and immune response also was present in the cat.38, 39, 40

Functions of KIM‐1 are incompletely understood and controversial. KIM‐1 likely has specific functions rather than just being a marker of tubular injury. KIM‐1 is coexpressed with dedifferentiation and proliferation markers in regenerating proximal tubule cells after ischemic injury in rats and humans, and is believed to contribute to the regenerative response.23, 24, 41 In addition, tubular cells that survive ischemic damage and express KIM‐1 develop a phagocytic phenotype, recognize phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells, and internalize such apoptotic cells thereby clearing tubular debris.42 Cleavage of KIM‐1 at the juxtamembranous region and release into urine is mediated by matrix metalloproteinase‐3 (MMP‐3).43 Ischemia, inflammation, or both with generation of reactive oxygen species and activation of MMP‐3 induce transcription of KIM‐1 and enhance cleavage.43, 44 Colocalization of KIM‐1 with vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and osteopontin has led some authors to propose KIM‐1 induction as an intermediary step in the development of tubulointerstitial damage and inflammation.41, 45, 46

Kidney injury molecule 1 in urine and kidney tissue was evaluated in samples from ill cats divided into 2 groups according to absence or presence of historical KD. Two cats of group A could have been classified by International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) criteria as having grade I AKI because they had progressive increases in SC concentration of ≥26.4 μmol/L (≥0.3 mg/dL), but these results remained within RI during a 48‐hour interval (http://www.iris-kidney.com, accessed February 2014). Other cats of group A might have experienced AKI during hospitalization, but repeated SC concentrations were not determined. Fifteen of 16 cats with a history of KD in group B might have been classified as chronic KD stage 2–4 by IRIS guidelines (http://www.iris-kidney.com, accessed January 2014).47, 48 However, because the cats were critically ill with unstable glomerular filtration rates (GFR), had variably received fluid therapy, repeated SC concentrations were not available and fasting could not be assured, we chose to indicate the actual SC concentrations rather than stratify a relatively small number of cats into IRIS stages. Several cats had normal SC concentration on admission but historically had increased SC concentration. This change was attributed to increased GFR that developed concurrent with hyperthyroidism or fluid therapy.49 Thirteen of 16 cats with “critical illness and previous KD” had proteinuria. However, neither blood pressure nor urine protein‐to‐creatinine ratio was consistently determined. Application of IRIS criteria is of benefit for staging KD in stable patients and initiating appropriate treatment. However, IRIS classification is challenging in patients with unstable KD and conditions such as hyperthyroidism. Several cats of group C had proteinuria, which was attributed to hematuria in 2 cases; and presence of sperm, high specific gravity or dry food diets in the other cases.50, 51 Lack of underlying renal disease could not be entirely eliminated.

Kidney injury molecule 1 positive results were obtained in 11 cats of group A and group B, but in none of the clinically healthy cats. KIM‐1 is shed from acutely injured tubular cells in rats, mice, and humans.23, 52, 53, 54 Therefore, KIM‐1 might be expected in urine of cats that experience hypotension, renal hypoperfusion and ischemia, or tubular toxic or inflammatory injury. Although neither the sensitivity of detecting KIM‐1 in urine nor the specificity for injury of specific segments of the nephron can be deduced from the data presented here, KIM‐1 was not detected in urine of healthy cats, and was detected in cats that had or may have had kidney injury. Positive UIA results developed in some cats concurrent with increasing SC concentration, or became negative with presumed resolution of hypotension or improvement of critical illness. Severe acute tubular injury may result in rapid and marked cellular KIM‐1 up‐regulation and then shedding into urine, and extensive death of tubular cells may result in subsequent lack of detection of KIM‐1 in urine or tissues.41, 55 If the dynamics of KIM‐1 are similar in cats, negative results may indicate large‐scale loss of tubular cells such as may occur in lily toxicity, or replacement with less differentiated cells during repair.46, 56 Therefore, it will be important to precisely determine the temporal appearance of KIM‐1 in urine in relation to well‐defined kidney injury. However, this is difficult to accomplish in studies involving clinical patients.

Kidney tissues for KIM‐1 IHC were available from 11 cases. In 8 cases, there was positive staining in proximal tubular cells although UIA results had been negative in 3 of these cats. Possible reasons for this discrepancy are that not all KIM‐1 expressed by tubular epithelium also is cleaved and shed into urine, that UIA is less sensitive than IHC, or that the protein is unstable in urine. Ideally, urine samples should be incubated with protease inhibitors and rapidly frozen before analysis, which was not feasible in this study for samples collected in a noninvasive manner from critically ill patients. Furthermore, a feline‐specific KIM‐1 UIA might have been more sensitive and yielded results that agree to a greater extent with IHC results, but such a UIA is unavailable at this time. Three cats had negative KIM‐1 IHC results although they had presumed acute exacerbation of chronic KD. In 2 of these cats, only small biopsies lacking the OSOM were available, therefore the region of the nephron in which KIM‐1 should be expressed was absent. The 3rd cat had severe chronic fibrotic KD, persistent marked increase in SC, and several days lapsed between exacerbation of KD and euthanasia. The most likely reason for lack of KIM‐1 staining in this case was loss of or fibrotic change in proximal tubular cells in an animal with end‐stage KD.

Six cats had positive KIM‐1 UIA results, whereas their SC concentrations were within RI. This finding is similar to those in rodents and people, where injured renal tubules up‐regulate and shed KIM‐1 into urine before clinically relevant increases in SC concentration.52, 57 Furthermore, SC concentration above a population‐derived RI is considered to be an insensitive indicator of decreased GFR, and “critical differences” in SC concentration over time within an individual may more accurately reflect changes in GFR.16, 17, 18, 58 Thus, from the limited number of cases included here, it appears that apparent detection of KIM‐1 in urine may be a very sensitive indicator of acute injury of tubular cells in cats without pre‐existing KD that experience kidney injury because of hypovolemia, hypotension, ischemia, toxic or septic insult, or that have acute injury superimposed on pre‐existing KD.

A limitation of this study was that samples from defined AKI were unavailable for use as positive controls. Furthermore, although antibodies in the UIA and IHC were directed to KIM‐1 regions similar in cats, rats and humans, sensitivity of both assays would likely be higher with antibodies matching precisely to feline KIM‐1 epitopes. Hence, preliminary evaluation of the UIA for rat KIM‐1 did not entail proper test validation, but rather proof‐of‐principle to justify future generation of feline‐specific reagents. Measurement of KIM‐1 gene transcripts by quantitative PCR was not deemed meaningful because induced expression is highly variable across different segments of the proximal convoluted tubule and nephron, and only comparing expression across identical nephron segments would be informative. This study was not meant to evaluate the specificity or sensitivity of nonfeline UIA or IHC assays, but rather to demonstrate KIM‐1 expression in the feline kidney and to identify shedding into urine. Further elucidation of the role of feline KIM‐1 in AKI will depend on development of more specific reagents.

In rodents and primates, KIM‐1 measurement compared favorably in sensitivity and specificity to other urinary biomarkers for detection of AKI. In rat experimental renal ischemia and toxic injury, measurement of urine KIM‐1 was more sensitive than SC concentration, BUN, urine glucose, or urine N‐acetyl‐beta‐d‐glucosaminidase (NAG).26 Similarly, in humans KIM‐1 assays outperformed NAG, MMP3, and γ‐glutamyl transpeptidase assays for detection of AKI.54 Data regarding performance in companion animals are lacking to date, but based on preliminary findings reported here, further investigation of KIM‐1 as a biomarker of KD in cats appears warranted.

Supporting information

Table S1. Individual cat signalment, clinicopathologic data, etc.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Pet Trust Foundation at the Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

This study was performed in the Department of Pathobiology at the University of Guelph.

Presented in part as an abstract at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists in Montreal (2013). We acknowledge critical review of this manuscript by C. Schmiedt, University of Georgia.

Footnotes

V5.5.3; Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand

Qiagen, Mississauga, ON

Invitrogen, Mississauga, ON

Sigma Aldrich, Burlington, ON

Laboratory Services Division, Guelph, ON

Animal Health Laboratory, University of Guelph

Roche, Mississauga, ON

R‐Rena‐Strip; BioAssay Works, Ijamsville, MD

R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN

DakoCytomation, Mississauga, ON

Vector Laboratories, Burlington, ON

References

- 1. Bartges JW. Chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2012;42:669–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lulich JP, Osborne CA, O'Brien TD, Polzin DJ. Feline renal failure: Questions, answers, questions. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1992;14:127–152. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chakrabarti S, Syme HM, Elliott J. Clinicopathological variables predicting progression of azotemia in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jepson RE, Brodbelt D, Vallance C, et al. Evaluation of predictors of the development of azotemia in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Segev G, Nivy R, Kass PH, Cowgill LD. A retrospective study of acute kidney injury in cats and development of a novel clinical scoring system for predicting outcome for cats managed by hemodialysis. J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:830–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: Report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 2007;11:R31. doi:10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2008;36:S141–S145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Uchino S, Bellomo R, Bagshaw SM, Goldsmith D. Transient azotaemia is associated with a high risk of death in hospitalized patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:1833–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monaghan K, Nolan B, Labato M. Feline acute kidney injury: 1. Pathophysiology, etiology and etiology‐specific management considerations. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Venkatachalam MA, Griffin KA, Lan R, et al. Acute kidney injury: A springboard for progression in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2010;298:1078–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Amodeo S, et al. The severity of acute kidney injury predicts progression to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2011;79:1361–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chawla LS, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: An integrated clinical syndrome. Kidney Int 2012;82:516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Finco DR, Duncan JR. Evaluation of blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine concentrations as indicators of renal dysfunction: A study of 111 cases and a review of related literature. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1976;168:593–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lapointe C, Bélanger MC, Dunn M, et al. N‐acetyl‐beta‐d‐glucosaminidase index as an early biomarker for chronic kidney disease in cats with hyperthyroidism. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Hoek I, Daminet S, Notebaert S, et al. Immunoassay of urinary retinol binding protein as a putative renal marker in cats. J Immunol Methods 2008;329:208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reinhard M, Erlandsen EJ, Randers E. Biological variation of cystatin C and creatinine. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2009;69:831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Selvin E, Juraschek SP, Eckfeldt J, et al. Within‐person variability in kidney measures. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;61:716–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baral RM, Dhand NK, Freeman KP, et al. Biological variation and reference change values of feline plasma biochemistry analytes. J Feline Med Surg 2014;16:317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cowgill L, Lanngston C. Acute kidney insufficiency In: Bartges J, Polzin D, eds. Nephrology and Urology of Small Animals. Chichester, UK; Ames, IA: Wiley‐Blackwell; 2011:472–532. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thoen ME, Kerl ME. Characterization of acute kidney injury in hospitalized dogs and evaluation of a veterinary acute kidney injury staging system. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2011;21:648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harison E, Langston C, Palma D, Lamb K. Acute azotemia as a predictor of mortality in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:1093–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee YJ, Chan JP, Hsu WL, et al. Prognostic factors and a prognostic index for cats with acute kidney injury. J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ichimura T, Bonventre JV, Bailly V, et al. Kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1), a putative epithelial cell adhesion molecule containing a novel immunoglobulin domain, is up‐regulated in renal cells after injury. J Biol Chem 1998;273:4135–4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bailly V, Zhang Z, Meier W, et al. Shedding of kidney injury molecule‐1, a putative adhesion protein involved in renal regeneration. J Biol Chem 2002;277:39739–39748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ichimura T, Hung CC, Yang SA, et al. Kidney injury molecule‐1: A tissue and urinary biomarker for nephrotoxicant‐induced renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2004;286:F552–F563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vaidya VS, Ramirez V, Ichimura T, et al. Urinary kidney injury molecule‐1: A sensitive quantitative biomarker for early detection of kidney tubular injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006;290:517–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bonventre JV. Kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1): A specific and sensitive biomarker of kidney injury. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 2008;24:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pontius JU, O'Brien SJ. Genome Annotation Resource Fields–GARFIELD: A genome browser for Felis catus . J Hered 2007;98:386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Menotti‐Raymond M, David VA, Schäffer AA, et al. An autosomal genetic linkage map of the domestic cat, Felis silvestris catus. Genomics 2009;93:305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marchler‐Bauer A, Zheng C, Chitsaz F, et al. CDD: Conserved domains and protein three‐dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:D348–D452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chakrabarti S, Syme HM, Brown CA, Elliott J. Histomorphometry of feline chronic kidney disease and correlation with markers of renal dysfunction. Vet Pathol 2013;50:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brenner BM, Rector FC. The Kidney. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ivie SE, Fennessey CM, Sheng J, et al. Gene‐trap mutagenesis identifies mammalian genes contributing to intoxication by Clostridium perfringens ε‐toxin. PLoS One 2011;6:e17787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full‐length human and mouse cDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:16899–16903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Keren H, Lev‐Maor G, Ast G. Alternative splicing and evolution: Diversification, exon definition and function. Nat Rev Genet 2010;11:345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nozaki Y, Nikolic‐Paterson DJ, Snelgrove SL, et al. Endogenous Tim‐1 (Kim‐1) promotes T‐cell responses and cell‐mediated injury in experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012;81:844–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barclay AN. Ig‐like domains: Evolution from simple interaction molecules to sophisticated antigen recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:14672–14674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Freeman GJ, Casasnovas JM, Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH. TIM genes: A family of cell surface phosphatidylserine receptors that regulate innate and adaptive immunity [Internet]. Immunol Rev 2010;235:172–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang Z, Humphreys BD, Bonventre JV. Shedding of the urinary biomarker kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1) is regulated by MAP kinases and juxtamembrane region. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2704–2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Binné LL, Scott ML, Rennert PD. Human TIM‐1 associates with the TCR complex and up‐regulates T cell activation signals. J Immunol 2007;178:4342–4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Timmeren MM, van den Heuvel MC, Bailly V, et al. Tubular kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1) in human renal disease. J Pathol 2007;212:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ichimura T, Asseldonk EJ, Humphreys BD, et al. Kidney injury molecule‐1 is a phosphatidylserine receptor that confers a phagocytic phenotype on epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1657–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lim AI, Chan LY, Lai KN, et al. Distinct role of matrix metalloproteinase‐3 in kidney injury molecule‐1 shedding by kidney proximal tubular epithelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012;44:1040–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ajay AK, Kim TM, Ramirez‐Gonzalez V, et al. A bioinformatics approach identifies signal transducer and activator of transcription‐3 and checkpoint kinase 1 as upstream regulators of kidney injury molecule‐1 after kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;25:105–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kuehn EW, Park KM, Somlo S, Bonventre JV. Kidney injury molecule‐1 expression in murine polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2002;283:1326–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 2011;121:4210–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boyd LM, Langston C, Thompson K, et al. Survival in cats with naturally occurring chronic kidney disease (2000–2002). J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:1111–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Paepe D, Daminet S. Feline CKD: Diagnosis, staging and screening—What is recommended? J Feline Med Surg 2013;15:S15–S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Adams WH, Daniel GB, Legendre AM. Investigation of the effects of hyperthyroidism on renal function in the cat. Can J Vet Res 1997;61:53–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palmore WP, Gaskin JM, Nielson JT. Effects of diet on feline urine. Lab Anim Sci 1978;28:551–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Osborne CA, Stevens JB, Ulrich LK. Urinalysis: A Clinical Guide to Compassionate Patient Care. Leverkusen, Germany: Bayer AG; Shawnee Mission, KS: Bayer Corp., Agricultural Division, Animal Health, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sabbisetti VS, Ito K, Wang C, et al. Novel assays for detection of urinary KIM‐1 in mouse models of kidney injury. Toxicol Sci 2013;131:13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Han WK, Bailly V, Abichandani R, et al. Kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1): A novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney Int 2002;62:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Han WK, Waikar SS, Johnson A, et al. Urinary biomarkers in the early diagnosis of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 2008;73:863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang PL, Rothblum LI, Han WK, et al. Kidney injury molecule‐1 expression in transplant biopsies is a sensitive measure of cell injury. Kidney Int 2008;73:608–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bonventre JV. Dedifferentiation and proliferation of surviving epithelial cells in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:S55–S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vaidya VS, Ford GM, Waikar SS, et al. A rapid urine test for early detection of kidney injury. Kidney Int 2009;76:108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Waikar SS, Betensky RA, Emerson SC, Bonventre JV. Imperfect gold standards for kidney injury biomarker evaluation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Individual cat signalment, clinicopathologic data, etc.