Abbreviations

- CLSI

Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute

- CNS

central nervous system

- FNA

fine needle aspirate

- rRNA

ribosomal ribonucleic acid

A 5‐year‐old neutered male Standard Poodle was evaluated by the emergency service at Texas A&M University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (TAMU VMTH) for inappetence and lethargy, of 3 months duration. These clinical signs occurred shortly after the dog was administered cyclosporine1 (5 mg/kg PO q24h) for biopsy‐confirmed sebaceous adenitis. Original biopsies were performed at another facility and showed diffuse sebaceous gland atrophy and minimal lymphohistiocytic and plasmacytic inflammation in 3 separate anatomic locations. Two months later, the cyclosporine dose was reduced (5 mg/kg PO q48h) with no improvement of clinical signs.

On presentation at TAMU VMTH, the dog was quiet, alert, and responsive, but lethargic and had multiple, raised, hairless epidermal masses on the dorsal cervical region and over the left tuber coxae, consistent with lesions of sebaceous adenitis. A firm gingival mass was noted over the left maxillary molar with a presumed diagnosis of a peripheral odontogenic fibroma. Results of a CBC, chemistry panel, urinalysis, quantified urine culture, thoracic radiographs, and abdominal ultrasound did not reveal any abnormalities, and the dog was discharged with instructions to discontinue cyclosporine and begin topical supportive treatment with Dermoscent spot‐on2 and Douxo Seborrhea3 shampoo for the sebaceous adenitis.

Two days after discharge, the dog was readmitted for acute abdominal pain and persistent lethargy and anorexia. New physical exam findings included a 2 × 2 cm subcutaneous mass on the left thigh, mild popliteal lymphadenopathy, a tense abdomen, general proprioceptive ataxia of the pelvic limbs, and caudal lumbar spinal pain. Repeat CBC and plasma chemistries included leukocytosis (21.1 cells/μL; reference interval, 6.0–17.0 cells/μL), neutrophilia (17 × 103 cells/μL; reference interval, 13–11.5 × 103/μL), monocytosis (1.89 × 103 cells/μL; reference interval, 0.15–1.25 × 103/μL), and mild hyperbilirubinemia (1.2 mg/dL; reference interval, 0–0.8 mg/dL). Baseline serum cortisol concentration, recheck abdominal ultrasound, joint fluid analysis, and lumbar spinal radiographs revealed no abnormalities.

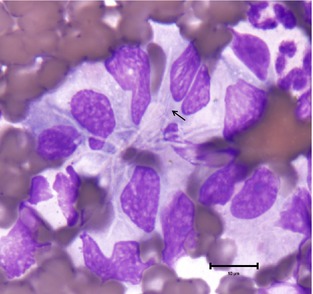

Cytologic examination of Diff‐Quik4 stained smears made from the fine needle aspirates (FNAs) of the right and left popliteal lymph nodes revealed septic pyogranulomatous inflammation with mild reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Occasional macrophages contained multiple, thin, nonstaining linear structures (Fig 1). Staining with Kinyoun acid‐fast methods and Gram stain revealed acid‐fast positive and gram‐positive, beaded, filamentous organisms most consistent with Nocardia species. Actinomyces and Mycobacteria species were thought to be unlikely based on positive Kinyoun and negative cold acid‐fast staining. FNA samples from the right popliteal lymph node were also submitted for bacterial culture and susceptibility.

Figure 1.

Fine needle aspirate of left popliteal lymph node. An aggregate of macrophages with numerous, negative‐staining filamentous and branching bacteria and 1 small area of staining (arrow) (100× objective, Diff‐Quik).4

A magnetic resonance imaging study of the lumbar spinal cord was performed with a 3.0 T unit.5 The study included spin echo T1‐weighted (T1W) sequences, spin echo T2‐weighed (T2W) sequences, and short TI inversion recovery (STIR) sequences. T1W images were acquired before and after administration of IV gadolinium‐based MRI contrast (Magnevist,6 1 mL/10 lb). The vertebral body of L3 was expanded with suspected infiltration because of osteomyelitis. The lesion was hypointense on T2W images, mildly hyperintense on STIR images, and had mild postcontrast enhancement of the central part of the vertebral body of L3. Mild postcontrast enhancement of the body of L2 was suspected and the right medial iliac lymph node was enlarged. Cerebrospinal fluid obtained by atlanto‐occipital puncture was clear and colorless with normal nucleated cell count (2/μL; reference, <5/μL), increased total protein concentration (80 mg/dL; reference, <45 mg/dL) and positive Pandy; cytologic examination revealed 36% nondegenerative neutrophils, 35% macrophages, and 30% small lymphocytes. These findings were interpreted as secondary change to the osteomyelitis.

At this time, disseminated nocardiosis with secondary osteomyelitis of the vertebral body of L3 was suspected. The dog was treated with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim7 (28 mg/kg PO q12h) and clindamycin8(5 mg/kg IV q12h). Multimodal analgesics were used as pain became progressively more difficult to manage. A nasoesophageal tube was placed because of anorexia. As a result of the relatively high level of opioid analgesics, the dog began to regurgitate, and metoclopramide9 was initiated. Despite these efforts, within 3 days, the patient's neurologic status worsened, and subcutaneous and cutaneous masses developed. These masses were cytologically similar to those of the popliteal lymph node, with pyogranulamotous inflammation and nonstaining, linear bacteria. The dog was humanely euthanized and a full necropsy was performed with the owner's consent.

Relevant findings at necropsy included a slightly raised, firm, 2 × 2 × 0.5 cm dermal nodule on the right lateral metatarsus, a soft, 2.5 × 2 × 3 cm subcutaneous nodule on the right lateral thigh, and a multinodular, raised, 1 × 3 × 0.5 cm, ulcerated dermal nodule on the right lateral elbow. All were mottled red and yellow‐tan on cut section. Bilaterally the prescapular and popliteal lymph nodes were enlarged and soft with mucoid, yellow‐tan bulging nodules observed on cut surface, consistent with lymphadenitis. The retropharyngeal lymph nodes were bilaterally diffusely enlarged, soft, rounded, and reddish brown, consistent with reactive hyperplasia.

On microscopic examination of routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)‐stained slides, all dermal and subcutaneous nodules and affected lymph nodes were characterized by marked pyogranulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells and necrosis. Infectious agents were not initially detected. Mild pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis was noted in the body of the L3 vertebra. The liver, lungs, and kidneys were characterized by mild, multifocal pyogranulomatous inflammation. Gram stain and Fite's acid‐fast stain were performed on histologic sections from the thigh mass and L3 vertebra, revealing numerous, gram‐positive, acid‐fast positive, filamentous, beaded bacteria, consistent with Nocardia species. Representative routine H&E‐stained sections of the cerebral cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, brainstem, and cervical, thoracic and lumbar spinal cord were examined. No evidence of inflammation was observed.

Antemortem right popliteal lymph node and necropsy samples, including the tarsal and thigh masses, and both popliteal lymph nodes were cultured on Trypticase Soy Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (TSAII), MacConkey Agar (MAC), and anaerobic Phenylethyl Alcohol Blood Agar (PEA). Aerobic culture plates were incubated at 35°C in 10% CO2 (TSAII) or in ambient air (MAC). Anaerobic culture plates were placed in an anaerobic jar with a gas generator envelop and incubated at 35°C. Small adherent bacterial colonies with irregular edges on TSAII were observed on day 2. Catalase test was positive. Gram stain revealed nonspore‐forming, gram‐positive branching rods. Modified Kinyoun's acid‐fast stain was positive. The colonial morphology and microscopic characteristics suggested Nocardia‐like organisms. For identifying the species, the first 500 bp of the 16S rRNA gene was determined and GenBank BLAST search revealed 100% identity between the query sequence and the 16s rRNA gene sequence of Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis. Based on CLSI MM18‐A Interpretive Criteria (≥99.6% for species identification), the isolate was identified as N. pseudobrasiliensis (CLSI, 2008).

Discussion

This is a case report of an immunosuppressed dog with disseminated disease involving dermal and subcutaneous lesions, lymphadenopathy, and severe and rapidly progressive spinal pain because of central nervous system involvement, caused by N. pseudobrasiliensis. Although a diagnosis of nocardiosis was quickly obtained and standard medical treatment and supportive care were initiated, the patient's condition rapidly declined, and euthanasia was elected.

To the authors' knowledge, N. pseudobrasiliensis infections have not been reported in the veterinary literature. In humans, this species has been shown to cause more aggressive and disseminated disease than other species of Nocardia.1, 2 Human cases have been reported in both immunocompromised individuals and apparently immunocompetent, elderly patients.3, 4 The dog in this case had a disseminated and rapidly progressive disease course, despite standard treatment. This raises concern that this species will be associated with more severe disease in veterinary patients. Human cases of N. pseudobrasiliensis have shown different antibiotic susceptibility than other species of Nocardia.1, 2, 5 In addition, recent literature has shown N. pseudobrasiliensis to have the highest resistance to more than 1 commonly used drug, including trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, which was once considered effective for all species of Nocardia.6 Molecular tests for the species of suspected Nocardia infections should be determined for antemortem cases to initiate appropriate treatment and help determine potential for dissemination, prognosis, or both.

Nocardia is a genus of soil‐dwelling, aerobic actinomycete bacteria which occasionally causes disease in veterinary patients. Because of their fungal‐like morphology, Nocardia spp. have previously been mistaken for fungal organisms.7 Knowledge of the morphologic features of Nocardia spp. and the use of additional stains can be used to aid in identification and differentiation from Actinomyces or Mycobacteria spp. Nocardia organisms are thin (approximately 0.5–1 μm in diameter), filamentous, and can exhibit branching. The bacteria sometimes display a beaded appearance.8 With Romanowsky stains (ie, Diff‐Quik, Wright's stain), bacteria may stain light blue, but are often only identified as nonstaining linear structures within inflammatory cells (Fig 1). They are gram‐positive and Grocott's Methenamine Silver positive and partially acid‐fast with modified Kinyoun, Fite's, or Ziehl‐Neelsen methods.

Molecular techniques to confirm and determine the species of Nocardia infections are only rarely performed in veterinary medicine; however, reported isolates include N. asteroides, N. nova, N. farcinica, N. otitidiscaviarum, and N. abscessus.7, 9 Nocardia species most commonly isolated from people include members of N. asteroides complex and N. brasiliensis.10

Most commonly, Nocardia infections present as draining cutaneous lesions or pleuropneumonia in dogs and cats, and mastitis in cattle.7, 11 Reported cases of Nocardia infection invading the central nervous system are rare. Organisms most consistent with Nocardia were found within multiple brain abscesses and a mediastinal mass in a dog.12 Gram‐positive, partially acid‐fast, beaded organisms, suspected to be Nocardia sp., were found on postmortem examination of pulmonary and spinal cord lesions in a dog.13 Bradney published a case of vertebral osteomyelitis caused by an unknown species of Nocardia.14 That animal had a dermal scar over the area of the spine where the osteomyelitis was found, making it possible that this vertebral infection was caused by a penetrating wound and not necessarily hematogenous spread. With the exception of superficial lesions from the historic sebaceous adenitis, the dog in our report had no history of dorsal lesions, making hematogenous spread of the bacteria to the vertebral column more likely. Confirmatory culture and determination of species were not performed in the above‐mentioned, previously published case reports.12, 13, 14 The intractable pain observed in this case was also seen in a case of disseminated nocardiosis caused by N. abscessus.7 With that case, no necropsy was performed, but CNS lesions were suspected because of severe, generalized pain.

Similar to the current patient, previous case reports of Nocardia spp. involving the central nervous system occurred in animals receiving immunosuppressive drugs, either corticosteroids or cyclosporine.12, 13, 14 In addition, several reports of subcutaneous and pulmonary infection with Nocardia spp. in veterinary patients have occurred after chronic cyclosporine administration.7, 15 Dogs were treated with cyclosporine anywhere from 2 months to 3 years, with an average of 14 months.7, 12, 13, 15 Individual doses varied from 3.5 to 5 mg/kg and dosing frequency ranged from once daily to three times weekly. The dose of cyclosporine used in this patient was 5 mg/kg PO every 24 hours for approximately 2 months before development of new dermal lesions, inappetence, and lethargy. At that time, the dosing frequency was decreased to every 48 hours.

Cyclosporine inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, degranulation, and superoxide generation.16 In addition, activation and proliferation of T lymphocytes is reduced because of the inhibition of cytokines.17 The result of long‐term use may lead to increased susceptibility to infection. Patients on immunosuppressive drugs should be monitored frequently for secondary infectious disease.

Three of the reported dogs that developed nocardiosis after cyclosporine administration were also on ketoconazole (5–7.5 mg/kg once to twice daily).12, 13, 15 One case had no reported decrease in dose of cyclosporine after introduction of ketoconazole.15 One animal had received cyclosporine for 2 years and had only started ketoconazole 6 months before presentation for disseminated nocardiosis, no concurrent decrease in cyclosporine was noted. Ketoconazole inhibits cytochrome P450 oxidative enzymes in the liver; these enzymes are imperative to the metabolism of cyclosporine.18, 19 Therefore, ketoconazole can make small doses of cyclosporine more potent, which can be beneficial if cost of cyclosporine is a factor. However, when ketoconazole is added to cyclosporine without a decrease in cyclosporine dose, the serum concentration of cyclosporine is markedly increased.12 This phenomenon has also been reported with other drugs, such as fluconazole.20

Successful treatment of bacterial infections, including cases of nocardiosis, requires effective antimicrobials, supportive care, and monitoring. Human cases of nocardiosis have shown that culture and susceptibility, as well as species identification, are critical for appropriate therapeutic choices of antimicrobial drugs and determination of prognosis.1, 2 The dog reported in this case was started on sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim9 and clindamycin5 as soon as the presumptive diagnosis of nocardiosis was made. These drugs are considered standard treatments for Nocardia infections in dogs and cats. Imipenim, often the drug of choice in human cases of nocardiosis, is frequently ineffective against N. pseudobrasiliensis. It is infrequently used in veterinary medicine for nocardiosis as other antibiotics are often clinically effective, and Imipenim is reserved for cases that do not respond initially to treatment. Human isolates of N. pseudobrasiliensis have been shown to be most susceptible to combination treatment of sulfa drugs and ciprofloxacin.1, 2, 21 However, susceptibility varies between reported cases, indicating the need for susceptibility testing.22

Susceptibility testing was performed on this isolate and revealed an identical pattern to most human cases of N. pseudobrasiliensis (Table 1). Findings seen in both human isolates and the current isolate included: resistance to Imipenim and susceptibility to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and clarithromycin. Other Nocardia species (N. nova, N. farcinica, and N. cyriacigeorgica) have been shown to have decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones such as, ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, and pradofloxacin in veterinary patients.23 These results verify that N. pseudobrasiliensis has different susceptibilities than other, more common, species of Nocardia seen in veterinary species. Although the current patient was treated with at least 1 suitable drug according to the susceptibility testing, it is possible the patient did not respond because of advanced disease, an ineffective dose, or the lack of combination treatment, the latter of which has been needed in human patients with Nocardia infections.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing on Nocardia isolate.

| Antimicrobial | MIC (μg/mL) | Range (μg/mL) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | ≤1.00 | 1–64 | Susceptible |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 32.00 | 2/1–64/32 | Resistant |

| Cefepime | >32.00 | 1–32 | Resistant |

| Cefoxitin | >128.00 | 4–128 | Resistant |

| Ceftriaxone | >64.00 | 4–64 | Resistant |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.50 | 0.12–4 | Susceptible |

| Clarithromycin | 0.25 | 0.03–16 | Susceptible |

| Doxycycline | 16.00 | 0.12–16 | Resistant |

| Imipenem | >64.00 | 2–64 | Resistant |

| Linezolid | ≤1.00 | 1–32 | Susceptible |

| Minocycline | 8.00 | 1–8 | Resistant |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.25 | 0.25–8 | Susceptible |

| Tigecycline | 1.00 | 0.015–4 | No interpretation possiblea |

| Tobramycin | ≤1.00 | 1–16 | Susceptible |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 2.00 | 0.25/4.75–8/152 | Susceptible |

No interpretive criteria (ie, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute or drug manufacturer information) available for the interactions between antimicrobial and Nocardia species.

Conclusion

We present a case of disseminated nocardiosis in an immunosuppressed dog caused by a novel species in veterinary medicine, N. pseudobrasiliensis. Although the primary route of infection was unclear in this case, possible origins for disseminated infections include pulmonary, gastrointestinal, or cutaneous entry. Primary cutaneous inoculation is given the highest consideration in this case because of the lack of histologic lesions in the lungs or GI tract; however, this is purely speculation. Although a diagnosis was reached quickly, unmanageable pain, rapid disease progression, and apparent failure of standard antimicrobial treatment protocols also make this case unique. While further cases are needed to determine the trends of this species in veterinary patients, human infections of N. pseudobrasiliensis have a different antibiotic susceptibility and are associated with a more aggressive clinical disease course and increased mortality. When a presumptive diagnosis of Nocardia is reached, further diagnostics such as determination of species and susceptibility panels are warranted to determine the appropriate treatment and potentially aid in prognosis.

Acknowledgment

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Case presentation: Charles Louis Davis foundation for the advancement of veterinary and comparative pathology, 23rd Annual Southcentral Division Conference and Slide Seminar. October 4‐5, 2013. Galveston, TX. Informed of plans to publish.

Footnotes

Cyclosporine; Novartis, Greensboro, NC

Dermoscent spot‐on; Laboratoire de Dermo‐Cosmetique Animole, Castres, France

Douxo Seborrhea; Sogeval Laboratories, Inc, Coppell, TX

Diff‐Quik; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Newark, DE

Magnetom Verio; Siemens, Malvern, PA

Magnevist: (the gadolineum) – Bayer; Wayne, NJ

Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim; Amneal Pharmaceuticals of NY, Hauppauge, NY

Clindamycin; Hospira

Metoclopramide hydrochloride; Hospira, Lake Forest, IL

References

- 1. Wallace RJ Jr, Brown BA, Blacklock Z, et al. New Nocardia taxon among isolates of Nocardia brasiliensis associated with invasive disease. J Clin Microbiol 1995;33:1528–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ruimy R, Riegel P, Carlotti A, et al. Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis sp. nov., a new species of Nocardia which groups bacterial strains previously identified as Nocardia brasiliensis and associated with invasive diseases. In J Syst Bacteriol 1996;46:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown BA, Lopes JO, Wilson RW, et al. Disseminated Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis infection in a patient with AIDS in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28:144–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Waleed J, Rawling RA, Granato PA. Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis systemic infection in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Micro Newslett 2012;34:9. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Udhe KB, Pathak S, McCullum I Jr, et al. Antimicrobial‐resistant Nocardia isolates, United States, 1995–2004. Clin Inf Dis 2010;51:1445–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schlaberg R, Fisher MA, Hanson KE. Susceptibility profiles of Nocardia isolates based on current taxonomy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58:795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacNeill AL, Steeil JC, Dossin O, et al. Dissemination nocardiosis caused by Nocardia abscessus in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol 2010;39:381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Larone DH. Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification, 4th ed Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ribeiro MG, Salerno T, De Mattos‐Guaraldi AL, et al. Nocardiosis: An overview and additional report of 28 cases in cattle and dogs. Rev Inst Med Tropo Sao Paulo 2008;50:177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: Updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:403–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown‐Elliot BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory feature of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:259–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith PM, Haughland SP, Jeffery ND. Brain abscess in a dog immunosuppressed using cyclosporine. Vet J 2007;173:675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paul AE, Mansfield CS, Thompson M. Presumptive Nocardia spp. infection in a dog treated with cyclosporine and ketoconazole. N Z Vet J 2010;58:265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bradney IW. Vertebral osteomyelitis due to Nocardia in dog. Aust Vet J 1985;62:315–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siak MK, Burrows AK. Cutaneous nocardiosis in two dogs receiving ciclosporin therapy for the management of canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2013;24:453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spinsani S, Fabbri E, Muccinelli M, et al. Inhibition of neutrophil responses by cylcosporin A. An insight into molecular mechanisms. Rheumatology 2001;40:794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kobayashi T, Momoe Y, Iwasaki T. Cyclosporine A inhibits the mRNA expressions of IL‐2, IL‐4 and IFN‐gamma but not TNF‐alpha, in canine mononuclear cells. J Vet Med Sci 1997;69:887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mouatt JG. Cyclosporin and ketoconazole interaction for treatment of perianal fistulas in the dog. Aust Vet J 2002;80:207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patricelli AJ, Hardie RJ, McAnulty JE. Cyclosporine and ketoconazole for the treatment of perianal fistulas in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002;220:1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katayama M, Igarashi H, Tani K, et al. Effect of multiple oral dosing of fluconazole on the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine in healthy Beagles. J Vet Med Sci 2008;70:85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lebeaux D, Lanternier F, Degand N, et al. Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis as an emerging cause of opportunistic infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:656–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seol CA, Heungsup S, Duck‐Hee K, et al. The first Korean case of disseminated mycetoma cause by Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis in a patient on long‐term corticosteroid therapy for the treatment of microscopic polyangitis. Ann Lab Med 2013;33:203–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Govendir M, Norris JM, Hansen T, et al. Susceptibility of rapidly growing mycobacteria and Nocardia isolates from cats and dogs to pradofloxacin. Vet Microbiol 2011;153:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]