Abstract

Craniopharyngiomas are the third most common pediatric brain tumor and most common pediatric suprasellar tumor. Contemporary treatment of craniopharyngiomas utilizes limited surgery and radiation in an effort to minimize morbidity, but the long-term health status of patients treated in this fashion has not been well described. The purpose of this study was to analyze the health status of long-term survivors of pediatric craniopharyngioma treated primarily with radiation and conservative surgical resection. Medical records of all long-term survivors of craniopharyngioma treated at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital and then transferred to the long-term follow-up clinic were reviewed. The initial cohort comprised 55 patients. Of these, 51 (93%) were alive at the time of this analysis. The median age at diagnosis was 7.1 years (range, 1.2–17.6 years), and 29 (57%) were male. At the time of analysis, the median survival was 7.6 years (range, 5.0–21.3 years). Diagnosis and treatment included surgical biopsy, resection (n=50), and radiation therapy (n=48). Only one patient received chemotherapy. Polyendocrinopathy was the most common morbidity, with hypothyroidism (96%), adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency (84%), and diabetes insipidus (53%) occurring most frequently. Half were hypogonadal, and 33 (65%) were overweight or obese. The most common neurologic problems included shunt dependence (37%), seizures (28%), and headaches (39%). Psychological and educational deficits were also identified in a significant number of these individuals. Despite efforts to reduce morbidity in these patients, many survivors remain burdened with significant medical complications. In a small percentage of patients, these may result in death even during extended remission of craniopharyngioma. Due to the broad spectrum or morbidities experienced, survivors of craniopharyngioma continue to benefit from multidisciplinary care.

Keywords: health status, craniopharyngioma, pediatric, survivors

Craniopharyngiomas are the third most common pediatric brain tumor, accounting for about 10% of the total, and are the most common pediatric suprasellar tumor (Poretti, Grotzer, Ribi, Schonle, & Boltshauser, 2004). The median age at diagnosis is 8 years, and the racial and gender distributions are about equal. Craniopharyngiomas are histologically benign and do not metastasize or spread in an aggressively invasive manner. These tumors frequently adhere to nearby brain tissue, making surgical resection difficult, and can cause brain damage by direct infiltration, compression, and inflammation (Scarzello et al., 2006). Because these tumors typically occur in the center of the brain near vital structures such as the optic nerve, hypothalamus, or pituitary gland, devastating clinical effects are often noted.

Historically, long-term survival rates of 80% to 90% have been achieved with aggressive surgical resection (Karavitaki, Cudlip, Adams, & Wass, 2006) (Garre & Cama, 2007) (Morris et al., 2007) (Merchant et al., 2002). However, successful therapy for this tumor cannot be measured by survival alone. Life-altering, treatment-related morbidity is common due to damage to the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus. More recent treatment of craniopharyngioma has included limited surgery and the addition of radiation, but this can still cause additional damage to normal brain tissue. Most patients present with a combination of neurological, endocrine, and somatic effects that may be permanent and may even become exacerbated after treatment. This damage is often associated with excessive long-term multisystem morbidity and mortality despite a high cure rate. The long-term health status of conservatively managed craniopharyngioma survivors has not been well described. Thus, the purpose of this study was to analyze the health status of pediatric craniopharyngioma survivors who were treated with limited surgery with or without radiation therapy or chemotherapy at our hospital.

Methods

Patient Selection

Approval from the institutional review board of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (Memphis, TN) for a retrospective medical record review was obtained. The hospital records of all long-term survivors of craniopharyngioma who were treated at St. Jude and transferred for follow-up to the long-term After Completion of Therapy (ACT) Clinic were examined. Patients had to be 5 years from diagnosis in order to be transferred to the ACT clinic. All patients had a diagnosis of craniopharyngioma between 1987 and 2003. Data recorded included sex, race, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, treatment variables (i.e., surgery alone, surgery with radiation therapy, or surgery with radiation therapy and chemotherapy). The history of a shunt placement was also noted.

Health Status Measures

An organ-system analysis included 11 domains of health status: vision, hearing, cardiovascular function, endocrine status, gastrointestinal problems, hematological status, musculoskeletal integrity, neurological status, neurocognitive functioning, genitourinary function, and pubertal progression/reproductive status. Variables within each domain were coded as present, absent, no information available, or information not applicable, such as with gender-specific issues.

Analysis

Demographic and treatment data were characterized with incidence rates. The rates of long-term systemic morbidity were described. Incidence rates were calculated for endocrine and neurological outcomes. Overall survival time was measured from patients’ diagnosis date to the date of death. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve and the estimated survival rates 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis were calculated. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.

Results

Our initial cohort comprised 55 patients. At the time of this analysis, 51 (93%) were alive. The demographics of this group are summarized in Table 1. Among the 51 survivors (22 male), the median age at diagnosis was 7.1 years (range, 1.2–17.6 years). At the time of analysis, the median survival was 7.6 years (range, 5.0–21.3 years). Treatment included surgical biopsy or resection (n=50) and/or radiation therapy (n=48). Only one patient received chemotherapy. The most common morbidities in this cohort were polyendocrinopathy, neurological abnormalities, and neurocognitive problems.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | Total |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male (%) | 22 (43.1) |

| Female (%) | 29 (56.9) |

| Race | |

| White (%) | 40 (78.4) |

| Black (%) | 11 (21.6) |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| Median (min-max) | 7.1 (1.2–17.6) |

| Years from diagnosis to long-term follow-up | |

| Median (min-max) | 7.6 (5.0–21.3) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery alone (%) | 5 (9.8) |

| Surgery + radiation therapy only (%) | 44 (86.3) |

| Surgery + radiation therapy + chemotherapy (%) | 1 (2.0) |

| History of shunt placement | |

| Yes (%) | 21 (41.2) |

| No (%) | 30 (58.8) |

Endocrinopathies and metabolic complications are listed in Table 2. Of the 51 survivors, 49 had hypothyroidism, 47 had adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency, and 27 had diabetes insipidus. Half were hypogonadal, and 33 were overweight or obese. Low bone mineral density was found in 21 survivors. Most survivors (39) had 2 or more endocrinopathies.

TABLE 2.

Incidence of Endocrine Outcomes

| Variables | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Hypothyroidism | 49 (96) |

| Growth hormone deficiency | 47 (92) |

| ACTH deficiency | 43 (84) |

| Hypogonadism | 29 (27) |

| Diabetes insipidus | 27 (53) |

| Dyslipidemia | 23 (45) |

| Overweight | 21 (41) |

| Abnormal menses | 17 (33) |

| Abnormal menarche | 13 (26) |

| Obese | 12 (24) |

| Insulin resistance | 10 (20) |

| Perturbed pubertal timing | 8 (16) |

ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone

The frequency of neurologic problems is summarized Table 3. These morbidities included headaches, history of seizures, and abnormal cerebral vessels.

Table 3.

Incidence of Neurological Outcomes

| Variables | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Headache | 20 (39.2) |

| History of seizures | 14 (27.5) |

| Abnormal cerebral vessel | 19 (37.3) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 (15.7) |

| Hearing loss | |

| Unilateral | 3 (5.9) |

| Bilateral | 5 (9.8) |

| Oculomotor dysfunction | 6 (11.8) |

| Vision < 20/100 | |

| Unilateral | 6 (11.8) |

| Bilateral | 18 (35.3) |

Psychological and educational problems were also identified in many of these individuals. Ten survivors (20%) had documented neurocognitive deficits (FSIQ<80) that required an individual education plan for academic assistance. Two survivors obtained a special education certificate of attendance, 13 received a high school diploma, 2 were college graduates, and 1 completed a post-graduate degree. Fifteen survivors (29%) reported psychological problems, including depression, adjustment disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, Tourette syndrome, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Communication disorders in study patients included both written and verbal issues with comprehension and expression. These outcomes are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Incidence of Psychological and Educational Outcomes

| Variable | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Neurocognitive delay | 10 (19.6) |

| Individual educational plan for academic assistance | 10 (19.6) |

| Educational attainment | |

| Special education certificate of attendance | 2 (3.9) |

| High school diploma | 13 (25.4) |

| College graduate | 2 (3.9) |

| Post-graduate degree | 1 (1.9) |

| Psychological problems | 15 (29.4) |

| Communication disorder | 5 (9.8) |

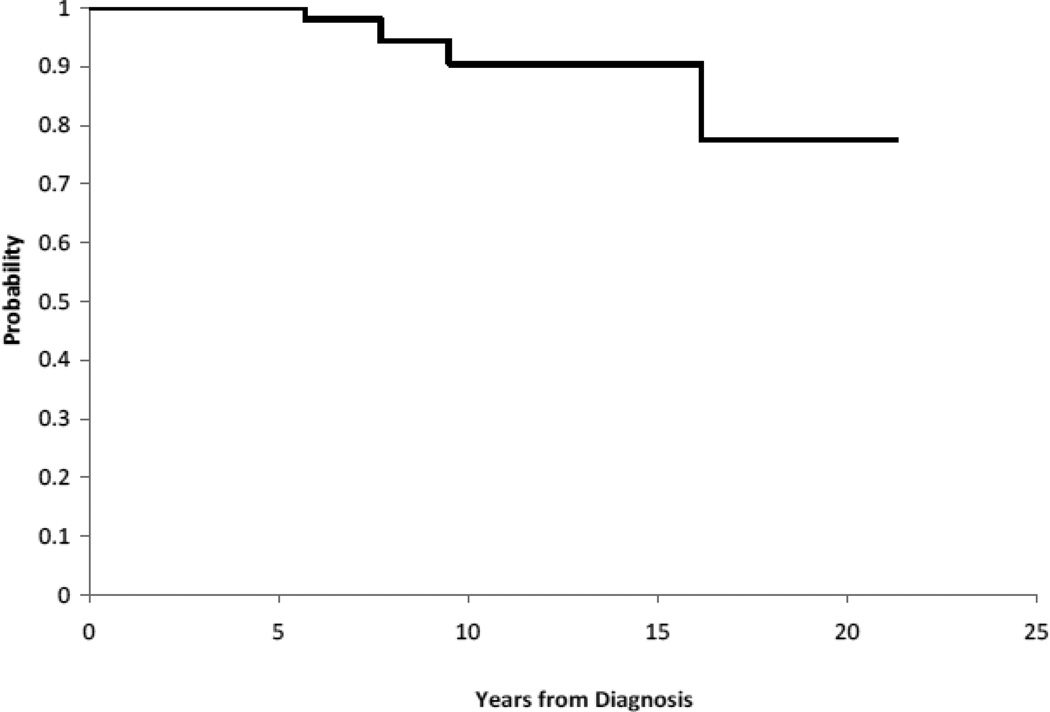

The review of systems revealed little morbidity related to other organ systems. Although the overall survival rate of patients who had survived at least 5 years from diagnosis was quite good (93%), there were four deaths in this cohort. Two patients died of metabolic complications, one died of cardiac arrest, and one died of recurrent disease. Patient characteristics of this group are summarized in Table 5, and the Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival versus time is shown graphically in Figure 1.

Table 5.

Characteristics of 4 Patients Who Died

| Patient | Sex-Race | Age at Diagnosis (years) |

Date of Diagnosis |

Initially Metastatic |

Date of Death |

Survival (years) |

Cause of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F-B | 12.9 | 10/13/1986 | No | 12/8/2002 | 26.2 | Diabetes, myocardial infarction |

| 2 | F-W | 1.1 | 1/17/1994 | No | 7/19/2003 | 9.5 | Metabolic complications, radionecrosis |

| 3 | F-B | 13.8 | 9/15/1997 | No | 5/30/2003 | 5.7 | Metabolic complications |

| 4 | M-B | 6.0 | 3/07/2000 | No | 11/18/2007 | 5.7 | Recurrent craniopharyngioma |

F = female; M = male; W = white; B = black

Figure 1.

Overall Survival for Long Term (≥ 5 years) Pediatric Craniopharyngioma Survivors

Discussion

Endocrine dysfunction was the most common morbidity seen in our cohort of craniopharyngioma survivors. Damage to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis from the tumor and treatment has been widely reported. The pituitary gland produces hormones that influence the activity of numerous target organs and promote body growth, protein synthesis, and fertility. These hormones also regulate glucose metabolism, cortisol/thyroid hormone production, and urine output. Among the patients in our series, 39 (76%) had more than one hormone deficiency or insufficiency. Reviewing advances in treatment and follow-up in childhood craniopharyngioma survivors, Muller (Muller, 2008) noted 85–95% of survivors suffered from multiple deficits of pituitary function. Irreversible diabetes insipidus followed 80–95% of complete tumor resections, and growth hormone deficiency occurred in 75% of cases.

Previous studies have suggested that craniopharyngioma survivors have significant health impairment (Armstrong et al., 2009) (Pedreira et al., 2006) (Ahmet et al., 2006). In fact, Ohmori and colleagues (Ohmori, Collins, & Fukushima, 2007) noted that craniopharyngiomas were associated with greater morbidity than any other brain tumor. Similarly, Morris and colleagues (Morris, et al., 2007) reported craniopharyngioma patients had a significantly greater risk of death from a medical condition than survivors of other central nervous system tumors, and hormone dysfunction was the predominant cause of death. In our series, 2 of the 4 deaths were from metabolic complications and sepsis. These deaths were potentially avoidable given available life-saving treatment. Both these patients had a history of panhypopituitarism and were prescribed chronic hormone replacement therapy. The degree of compliance with the prescribed regimens was not known. Brain tumor survivors may not be fully compliant with hormone replacement therapy due to neurocognitive impairment, seemingly asymptomatic conditions, reliance on a caregiver, or complexity of treatment. In addition, compliance with hormone replacement therapy may be complicated by the normal developmental rebellion of adolescence. (DiMatteo, Giordani, Lepper, & Croghan, 2002)

Similar to what has been reported in other studies, our review revealed that two thirds of survivors were either overweight or obese. Hyperphagia, hypothalamic obesity, and metabolic syndrome occur in half of all craniopharyngioma patients. Risk factors for the development of obesity in children surviving craniopharyngioma include hypothalamic involvement, height/weight at diagnosis, the need for growth hormone replacement or desmopressin therapy, and hydrocephalus requiring a shunt (Ahmet, et al., 2006) (Daousi, Dunn, Foy, MacFarlane, & Pinkney, 2005). Excessive weight gain as a manifestation of hypothalamic injury is generally underestimated because it often takes years to develop and therefore may be under recognized. Obesity significantly increases the risk of subsequent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in survivors (Mong, Pomeroy, Cecchin, Juraszek, & Alexander, 2008).

Merchant (Merchant, 2006) stressed that early assessment by a pediatric specialist is required to correctly manage endocrine deficiencies and to minimize morbidity or mortality. For example, early assessment facilitates plans for intervention. Education is another critical component of care to achieve compliance with hormone replacement therapy and to improve dietary habits. Neuroscience nurses can teach these patients by being available to answer questions, understanding the late morbidity survivors’ experience, and offering compassionate listening. Carroll (Carroll, 2008) wrote that such clear, focused communication can influence survivors’ health choices and support their commitment to complying with needed evaluations.

Focusing on endocrine deficits as the only consequence of craniopharyngiomas is a mistake. The loss of hormone function can often be treated with hormone replacement. However, neurological dysfunction frequently includes life-altering sequelae that cannot be corrected (Ullrich, Scott, & Pomeroy, 2005). In our series, neurological consequences included reduced vision, headache, seizures, and vasculopathy. It is difficult to compare the incidence of these morbidities to those noted in the literature, because reports of neurological morbidity after craniopharyngioma often combine outcomes for adult and pediatric patients. The most common neurological toxicities reported include changes in vision, seizures, and vasculopathy. Visual outcomes are compromised in a significant number of survivors, with as many as two thirds experiencing visual field deficits, reduced visual acuity, or at least quadrantanopia (Karavitaki et al., 2005). Vasculopathy after radiation is well documented (Perry & Schmidt, 2006). However in our series, only one third of our survivors had abnormal cerebral vessels; 15% had cerebrovascular disease. The relatively short follow-up in our sample may explain why this was not a more prominent finding.

Psychological and educational outcomes were difficult to evaluate in our sample because the median survivor age at the time of review was only 14.7 years. The developing brain of childhood is particularly vulnerable to injury, especially from radiation (Pimperl, 2005). Children treated for craniopharyngioma can have deficits of higher cortical functions that can impair educational and social performance (Bruce, Chapman, MacDonald, & Newcombe, 2008). Such deficits may not be identified in standard intelligence quotient (IQ) testing. Ullrich (Ullrich, et al., 2005) evaluated 16 craniopharyngioma patients and found that, in spite of normal IQ scores, survivors had specific word retrieval and memory deficits. These abnormalities localized damage to neural structures in the suprasellar region that are involved in transfer from immediate to long-term memory. In addition, longitudinal studies have shown that craniopharyngioma survivors have the slowest reactions times, highest levels of inattentiveness, and global problems with attention (Merchant, 2006). These deficits contribute to a diverse range of academic underachievement and challenges.

Our study has several limitations. Better defined treatment methods have continued to evolve since the survivors evaluated in this study were treated. However, our results are applicable to craniopharyngioma survivors who were treated between 1987 and 2003. Also, little information was available on the 4 patients who died. Therefore, data on their health status was not included in this analysis and may be a source of bias. Despite these limitations, our analysis adds important information to the literature on the prevalence and type of health status limitations experienced by pediatric craniopharyngioma survivors.

Implications for Nursing Care

The pervasive health status deficits identified in our study are the basis of a call to action for neuroscience nurses to become advocates for pediatric craniopharyngioma survivors. Nurses are in a unique position to assess patients’ risk for health problems, identify vulnerable individuals, and design specific educational/behavioral interventions to optimize their health status. These interventions need to incorporate the evolution of digital technologies such as programmed cellular phone text messaging, Web-based chat rooms, and other social media (O'Conner-Von, 2009). Nurses can join with computer programmers to design video games to improve survivors’ understanding and compliance with needed hormone replacement therapy and follow-up examinations. Social media websites utilizing or patterned after Facebook ®, Reddit ®, Fark ®, or Twitter ® could be used to communicate with survivors. Within these networks, content is selected, prioritized, and shaped by those using the service.

Craniopharyngioma survivors experience many challenges and a great deal of anxiety about their vulnerability. Frank discussions can lessen their anxiety. We have previously shown that nurses can help to create a positive listening environment in which survivors relate complete and honest information about their problems (Crom, Hinds, Gattuso, Tyc, & Hudson, 2005; Crom et al., 2006).

Conclusion

The number of children surviving craniopharyngiomas has steadily increased over the years, but these survivors can face years of significant medical complications. In a small percentage of patients, this can even include death from other causes during an extended remission of craniopharyngioma. Because these morbidities are so remarkably diverse, craniopharyngioma survivors can benefit greatly from multidisciplinary care and focused nursing interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Galloway, ELS, for editorial assistance.

Research grant support: This work was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

References

- Ahmet A, Blaser S, Stephens D, Guger S, Rutkas JT, Hamilton J. Weight gain in craniopharyngioma--a model for hypothalamic obesity. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(2):121–127. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2006.19.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Huang S, Ness KK, Leisenring W, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(13):946–958. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce BS, Chapman A, MacDonald A, Newcombe J. School experiences of families of children with brain tumors. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2008;25(6):331–339. doi: 10.1177/1043454208323619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SV. Gifts. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40(6):324. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crom DB, Hinds PS, Gattuso JS, Tyc V, Hudson MM. Creating the basis for a breast health program for female survivors of Hodgkin disease using a participatory research approach. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(6):1131–1141. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1131-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crom DB, Tyc VL, Rai SN, Deng X, Hudson MM, Booth A, et al. Retention of survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a longitudinal study of bone mineral density. J Child Health Care. 2006;10(4):337–350. doi: 10.1177/1367493506067886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daousi C, Dunn AJ, Foy PM, MacFarlane IA, Pinkney JH. Endocrine and neuroanatomic features associated with weight gain and obesity in adult patients with hypothalamic damage. Am J Med. 2005;118(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40(9):794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garre ML, Cama A. Craniopharyngioma: modern concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(4):471–479. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282495a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karavitaki N, Brufani C, Warner JT, Adams CB, Richards P, Ansorge O, et al. Craniopharyngiomas in children and adults: systematic analysis of 121 cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62(4):397–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karavitaki N, Cudlip S, Adams CB, Wass JA. Craniopharyngiomas. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(4):371–397. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant TE. Craniopharyngioma radiotherapy: endocrine and cognitive effects. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(Suppl 1):439–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant TE, Kiehna EN, Sanford RA, Mulhern RK, Thompson SJ, Wilson MW, et al. Craniopharyngioma: the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital experience 1984–2001. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(3):533–542. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mong S, Pomeroy SL, Cecchin F, Juraszek A, Alexander ME. Cardiac risk after craniopharyngioma therapy. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;38(4):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EB, Gajjar A, Okuma JO, Yasui Y, Wallace D, Kun LE, et al. Survival and late mortality in long-term survivors of pediatric CNS tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1532–1538. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller HL. Childhood craniopharyngioma. Recent advances in diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Horm Res. 2008;69(4):193–202. doi: 10.1159/000113019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Conner-Von S. Coping with cancer: a web-based educational program for early and middle adolescents. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2009;26(4):230–241. doi: 10.1177/1043454209334417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori K, Collins J, Fukushima T. Craniopharyngiomas in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43(4):265–278. doi: 10.1159/000103306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedreira CC, Stargatt R, Maroulis H, Rosenfeld J, Maixner W, Warne GL, et al. Health related quality of life and psychological outcome in patients treated for craniopharyngioma in childhood. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(1):15–24. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2006.19.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Schmidt RE. Cancer therapy-associated CNS neuropathology: an update and review of the literature. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;111(3):197–212. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimperl LC. Radiation as a nervous system toxin. Neurol Clin. 2005;23(2):571–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poretti A, Grotzer MA, Ribi K, Schonle E, Boltshauser E. Outcome of craniopharyngioma in children: long-term complications and quality of life. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(4):220–229. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarzello G, Buzzaccarini MS, Perilongo G, Viscardi E, Faggin R, Carollo C, et al. Acute and late morbidity after limited resection and focal radiation therapy in craniopharyngiomas. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(Suppl 1):399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich NJ, Scott RM, Pomeroy SL. Craniopharyngioma therapy: long-term effects on hypothalamic function. Neurologist. 2005;11(1):55–60. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000149971.27684.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]