Abstract

The t(8;21) translocation is one of the most frequent cytogenetic abnormalities in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and results in the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 rearrangement. Despite the causative role of the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion gene in leukaemia initiation, additional genetic lesions are required for disease development. Here we identify recurring ZBTB7A mutations in 23% (13/56) of AML t(8;21) patients, including missense and truncating mutations resulting in alteration or loss of the C-terminal zinc-finger domain of ZBTB7A. The transcription factor ZBTB7A is important for haematopoietic lineage fate decisions and for regulation of glycolysis. On a functional level, we show that ZBTB7A mutations disrupt the transcriptional repressor potential and the anti-proliferative effect of ZBTB7A. The specific association of ZBTB7A mutations with t(8;21) rearranged AML points towards leukaemogenic cooperativity between mutant ZBTB7A and the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion.

The t(8;21) translocation is often found in acute myeloid leukaemia but is not sufficient for development of the disease. In this study, the authors identify frequent mutations in the transcriptional repressor, ZBTB7A, in these patients and show that the mutations reduce DNA binding activity.

The t(8;21) translocation is often found in acute myeloid leukaemia but is not sufficient for development of the disease. In this study, the authors identify frequent mutations in the transcriptional repressor, ZBTB7A, in these patients and show that the mutations reduce DNA binding activity.

Block of myeloid differentiation is one of the hallmarks of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). First insights into this key mechanism were gained by the discovery of the t(8;21)(q22;q22) translocation, which was the first balanced translocation described in a tumour and results in the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion gene (also known as AML1/ETO)1,2. The RUNX1/RUNX1T1 rearrangement is one of the most frequent chromosomal aberrations in AML and defines an important clinical entity with favourable prognosis according to the World Health Organization classification3. The RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion protein disrupts the core-binding factor complex, and thereby blocks myeloid differentiation. However, in vivo models indicate the requirement of additional lesions, such as of KIT or FLT3 mutations, for leukaemogenesis as the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion gene alone is not sufficient to induce leukaemia4,5,6,7,8. In the present study, we set out to identify additional mutations in AML t(8;21) and discovered frequent mutations of ZBTB7A—encoding a transcription factor important for the regulation of haematopoietic development9 and tumour metabolism10. It is very likely that ZBTB7A mutations are one of the important missing links in RUNX1/RUNX1T1-driven leukaemogenesis.

Results

ZBTB7A is frequently mutated in AML t(8;21)

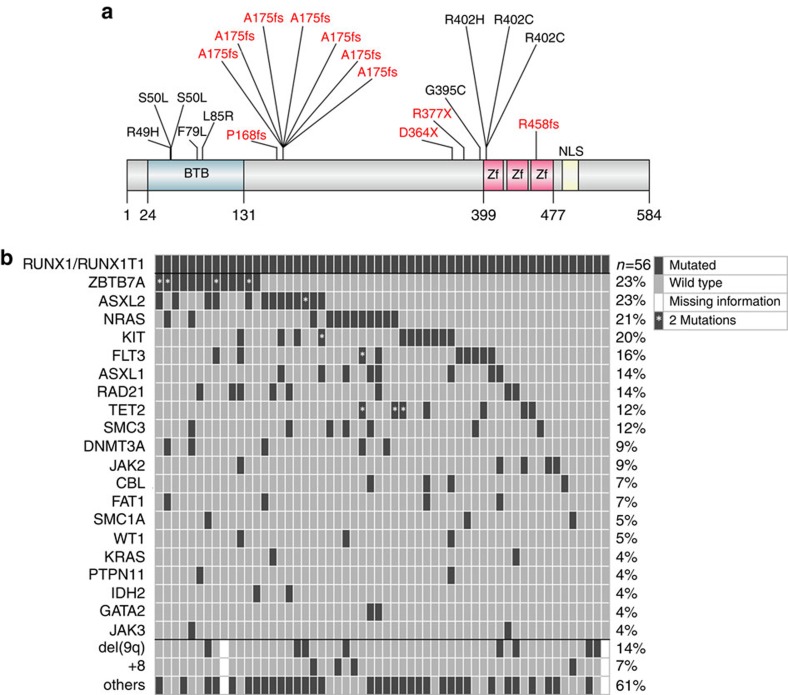

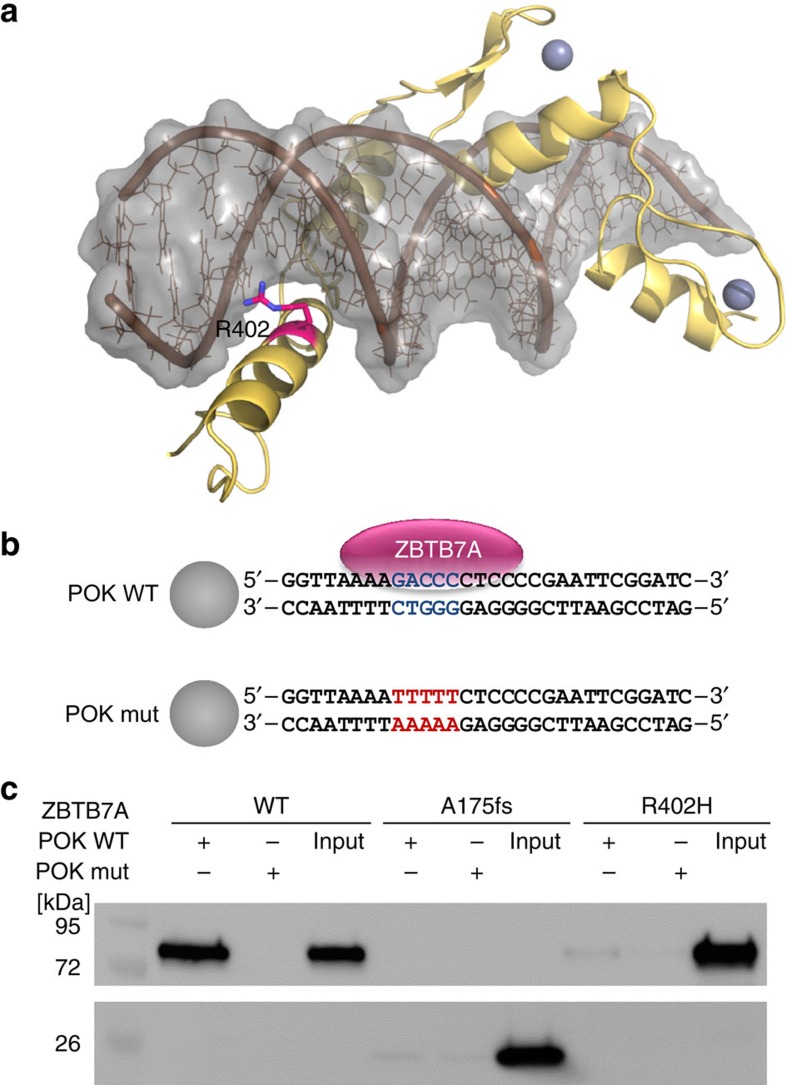

To identify additional cooperating mutations, we performed exome sequencing of matched diagnostic and remission samples from two AML patients with t(8;21) translocation and detected 11 and 12 somatic variants, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). ZBTB7A was the only mutated gene identified in both patients. ZBTB7A (also known as LRF, Pokemon and FBI-1) is a member of the POZ/BTB and Krüppel (POK) transcription factor family9, which is characterized by an N-terminal POZ/BTB protein–protein interaction domain and C-terminal C2H2 zinc fingers11. The first patient carried a homozygous missense mutation resulting in the amino-acid change R402H (NM_015898:exon2:c.1205G>A:p.R402H) affecting the highly conserved zinc-finger domain, while a heterozygous frameshift insertion (NM_015898:exon2:c.522dupC:p.A175fs) resulting in loss of the zinc-finger domain was identified in the second patient. Both mutations were validated by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 2). Using targeted amplicon sequencing of ZBTB7A and 45 leukaemia relevant genes, we screened 56 diagnostic AML t(8;21) samples, including one of the two samples analysed by exome sequencing (UPN 1), whereas for the other one (UPN 2) availability of material was insufficient. ZBTB7A mutations were identified in 13 of 56 patients (23%; Fig. 1a,b; Supplementary Table 3). Patient characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. Two recurring mutational hotspots (A175fs and R402) in exon 2 were identified altering or resulting in loss of the zinc-finger domain (Fig. 1a). It was previously shown that the zinc-finger domain of ZBTB7A is essential for DNA binding12. Structural modelling revealed that arginine 402 binds into the major groove of the DNA double helix and likely contributes to the affinity or sequence specificity of the DNA interaction of the zinc-finger domain of ZBTB7A (Fig. 2a). We confirmed that both ZBTB7A mutants A175fs and R402H fail to bind DNA (Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 1. ZBTB7A mutations in AML t(8;21).

(a) ZBTB7A protein (NP_056982.1) and identified mutations (red=truncating; black=missense) illustrated using IBS software31. Amino-acid positions are indicated below the graph. BTB, BR-C ttk and bab; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; Zf, zinc finger. (b) Mutational landscape of 56 diagnostic AML samples with t(8;21) translocation. Each column represents one patient, each line one of the analysed genes or cytogenetic markers.

Figure 2. Impact of ZBTB7A mutations on DNA binding.

(a) Model for the C-terminal zinc-finger domain of ZBTB7A comprising residues 382–488. The model is depicted as yellow ribbon with highlighted secondary structure. Zinc ions are shown as grey spheres. DNA is shown in brown with a grey molecular surface. R402 (purple) binds into the major groove and likely contributes to the affinity or sequence specificity of the DNA interaction of the zinc-finger domain. (b) Biotinylated oligonucleotides containing the ZBTB7A (alias: Pokemon) consensus binding motif (POK WT) or a mutant thereof (POK mut)14 used in DNA pull-down experiments. Spheres illustrate streptavidin-coated beads. (c) DNA pull-down using protein lysates from HEK293T cells expressing wild-type or mutant ZBTB7A. Western blot analysis shows that A175fs and R402H fail to bind oligonutides with a ZBTB7A-binding site (POK WT). Oligonucleotides with a mutated binding site (POK mut) were used as negative control. Input lanes were loaded with 10% of the protein lysate used for each binding reaction.

Variant allele frequency ranged from 5.4 to 76.2% (cut-off 2%) and 4 of 13 patients (31%) harboured two mutations of ZBTB7A. Fourteen of 17 mutations (82%) were validated by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 1). Somatic status was confirmed in a total of three patients with available remission samples. Thirty-two additional samples of t(8;21)-positive AML with inadequate sample availability for gene panel sequencing were analysed by Sanger sequencing of exon 2 (encoding amino acids 1–421) resulting in the identification of two ZBTB7A mutations (2/32; 6%). This lower mutation frequency might be due to the lower sensitivity of Sanger sequencing and incomplete coverage of the coding exons of ZBTB7A (we were not able to reliably amplify exon 3 encoding amino acids 422–584). To evaluate the consequences of truncating ZBTB7A mutations on the protein level, we performed western blot analysis for one patient with available material and detected a shorter form of the ZBTB7A protein resulting from the R377X mutation (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Recently, frequent ASXL2 mutations were identified in t(8;21) AML13. In our cohort, ZBTB7A and ASXL2 mutations occurred at similar frequencies (Fig. 1b) and 5 of 13 patients carried mutations in both genes; however, there was no significant association of mutated ZBTB7A and mutations in ASXL2 (Fisher's exact test, P=0.12) or any other recurrently mutated gene. Alterations of ASXL1 were mutually exclusive with genetic lesions of ZBTB7A suggesting alternative routes of leukaemogenesis. Similarly, mutations of ZBTB7A and KIT were exclusive in all, but one patient. In the exome data of 22 patients with inversion inv(16) (another rearrangement disrupting the core-binding factor complex in AML), we found a single ZBTB7A mutation (A211V). Of note, we did not find any ZBTB7A mutations by exome sequencing of 50 patients with cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML) or 14 AML patients with chromosomal aberrations other than t(8;21) or inv(16). These results point towards a specific association between ZBTB7A alterations and the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion.

Mutations disrupt the anti-proliferative function of ZBTB7A

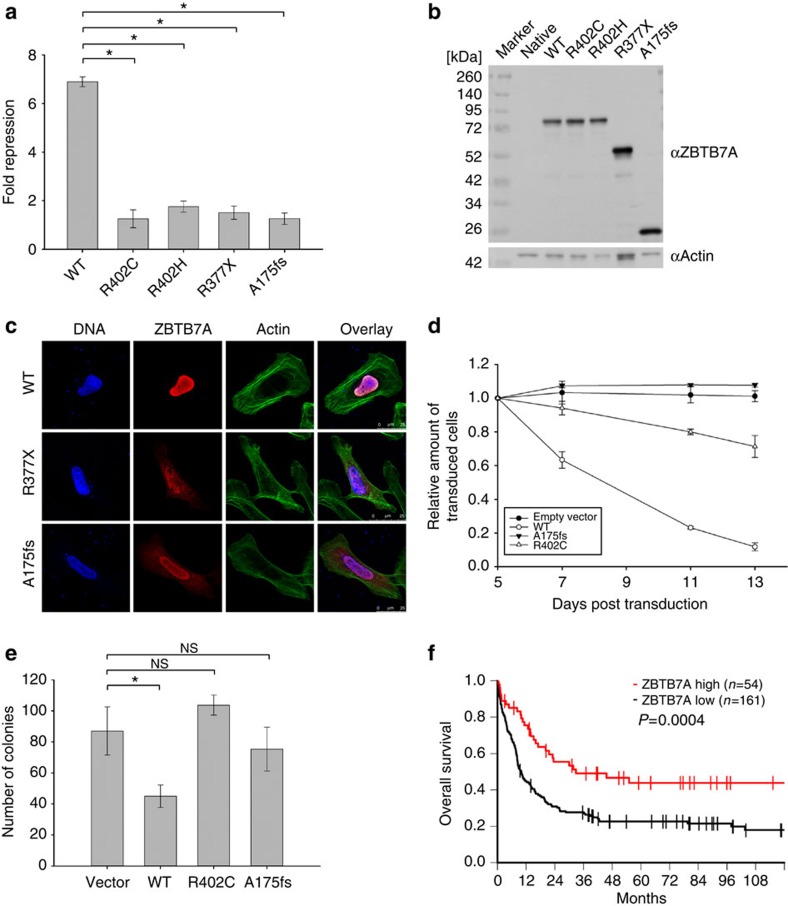

To assess the functional consequences of the identified ZBTB7A mutations, we performed luciferase reporter gene assays. It is known that ZBTB7A represses the expression of ARF (alternate open reading frame of CDKN2A)14. In contrast to wild-type ZBTB7A, the R402H, R402C, A175fs or R377X mutants failed to repress a luciferase reporter containing ZBTB7A-binding elements derived from the ARF promoter (Fig. 3a). Expression of ZBTB7A constructs was confirmed by western blot (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Functional consequences of ZBTB7A mutations and clinical relevance of ZBTB7A expression.

(a) Luciferase assay in transiently transfected HEK293T cells using the pGL2-p19ARF-Luc reporter combined with expression constructs for wild-type and mutant ZBTB7A. (b) Western blot of ZBTB7A constructs expressed in HEK293T cells. (c) Sub-cellular localization of ZBTB7A wild type, R377X and A175fs in transiently transfected U2OS cells. Scale bar, 25 μm. (d) Growth of Kasumi-1 cells stably expressing ZBTB7A wild type or mutants. (e) CFC assay of murine bone marrow lineage-negative cells co-expressing RUNX1/RUNX1T1 and wild-type or mutant ZBTB7A. (f) Overall survival of patients with CN-AML according to ZBTB7A expression (log-rank test, P=0.0004). *Two-tailed, unpaired Student's t-test, P<0.05; NS, not significant. Bar graphs or growth curves represent mean±s.d. of three independent experiments.

In light of recent reports about the negative regulation of glycolysis by ZBTB7A10, we assessed the expression of glycolytic genes (SLC2A3, PFKP and PKM) in the RNA-sequencing data from our AML t(8;21) patients (Supplementary Fig. 3). In ZBTB7A-mutated patients (n=5), we found a significantly higher expression of PFKP (Student's t-test, P=0.03) compared with patients without any detectable ZBTB7A mutation (n=11). On average, PKM and SLC2A3 also showed higher expression levels in patients with ZBTB7A mutations, but did not reach statistical significance (Student's t-test, P=0.17 and P=0.54, respectively). In the latter case, the difference in the mean values can be attributed mainly to an outlier in the ZBTB7A-mutated group with very high SLC2A3 expression. Expression levels of ZBTB7A were similar in both the patient groups, compatible with inactivation of ZBTB7A on the genetic level rather than on the transcriptional level.

The C-terminal part of ZBTB7A is important for nuclear localization15. Because some mutations result in loss of the C-terminal zinc-finger domain and nuclear localization signal, we evaluated the cellular localization of mutant ZBTB7A. Whereas wild-type ZBTB7A was detected in the nucleus, immunofluorescence staining of the A175fs and R377X mutants showed an altered cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 3c). In contrast, mutants R402H and R402C exhibited a variable cellular localization with cytoplasmic protein detectable only in a minor subset of cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). Amino-acid substitutions of R402 showed a smaller increase in cytoplasmic protein fraction compared with truncation mutants as analysed by western blot (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Ultimately, the observed effect of mutations on ZBTB7A localization remains to be confirmed in appropriate primary patient material, which was not available in our study.

In the t(8;21) translocation-positive AML cell line Kasumi-1, retroviral expression of wild-type ZBTB7A inhibited cell growth, whereas this anti-proliferative effect was not observed upon expression of the A175fs ZBTB7A mutant (Fig. 3d). The R402C mutant expressing Kasumi-1 cells showed a trend towards reduced cell growth, suggesting residual activity. On the basis of this observation, we expressed ZBTB7A wild type or its mutants together with the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion in lineage-negative murine bone marrow cells and performed colony-forming cell (CFC) assays. ZBTB7A expression led to a significant decrease in the number of colonies in primary CFC (87±12.6 versus 45±5.8, Student's t-test, P<0.0001), while this effect was lost for both mutants tested (Fig. 3e). These findings support an oncogenic cooperativity between RUNX1/RUNX1T1 and ZBTB7A mutations.

Prognostic relevance of ZBTB7A expression in CN-AML

The identification of a novel recurrently mutated gene demands the evaluation of its clinical relevance. We did not find a significant difference in overall or relapse-free survival between t(8;21)-positive AML patients with wild-type or mutant ZBTB7A (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, this evaluation was limited by the relatively small cohort size. Considering the potential role of ZBTB7A as tumour suppressor in AML and its anti-proliferative properties, we correlated ZBTB7A expression with clinical outcome in a larger cohort of AML patients (GSE37642). There was no significant difference in ZBTB7A expression levels between cytogenetic subgroups of AML (Supplementary Fig. 6). Remarkably, in over 200 CN-AML patients treated on clinical trial (NCT00266136), high expression of ZBTB7A was associated with a favourable outcome (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting a relevance in AML beyond the t(8;21) subgroup. The favourable prognostic impact of high ZBTB7A transcript levels was most obvious in elderly patients (age >60 years) and high ZBTB7A expression was associated with a ‘low molecular risk genotype' (mutated NPM1 without FLT3-ITD; Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Table 5). We validated the association of high ZBTB7A expression with favourable outcome in an independent CN-AML patient cohort16,17 (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Discussion

In summary, we have identified ZBTB7A as one of the most frequently mutated genes in t(8;21)-positive AML. Consistent with our findings, ZBTB7A mutations in 3 of 20 (15%) AML t(8;21) patients and 1 of 395 AML inv(16) patients were reported18 during the revision of the present manuscript. Our functional analyses indicate that ZBTB7A mutations result in loss of function, due to alteration or loss of the zinc-finger motives. Beyond DNA binding, the zinc-finger domain of ZBTB7A is also known to interact with TP53 and BCL6 (ref. 9). Thus, multiple pathways might be influenced by alteration or loss of the ZBTB7A zinc-finger domain. The N-terminal missense mutations in the BTB domain may result in failure of co-repressor recruitment. Considering that 4 of 13 of patients had more than one ZBTB7A mutation, our finding that overexpression of wild-type ZBTB7A leads to reduced proliferation of Kasumi-1 cells and a decreased number of CFCs of murine bone marrow cells, we suggest that ZBTB7A acts as a tumour suppressor in t(8;21)-positive AML. Initial studies characterized ZBTB7A as proto-oncogene in various tissues14,19. For example, Maeda et al. demonstrated that transgenic mice with Zbtb7a overexpression in the immature T- and B-lymphoid lineage develop precursor T-cell lymphoma/leukaemia14. In contrast, it was more recently shown that ZBTB7A can also act as a tumour suppressor. Overexpression of Zbtb7a in murine prostate epithelium did not result in neoplastic transformation; unexpectedly, Zbtb7a inactivation lead to the acceleration of Pten-driven prostate tumorigenesis20. Recently, somatic zinc-finger mutations of ZBTB7A were found at low frequencies (<5%) in a variety of solid cancers suggesting a common mechanism across tumour entities21. In fact, the de-repression of glycolytic genes upon deletion or mutation of ZBTB7A10,21 might underlie the loss of anti-proliferative properties that we observed for ZBTB7A mutants A175fs and R402C in the present study. Any inactivating alteration of ZBTB7A will likely increase glycolysis, and, thus, helps the tumour cells to produce more energy. Besides tumour metabolism, it is known that ZBTB7A also plays an important role in haematopoietic lineage fate decisions9. During lymphopoiesis ZBTB7A regulates B-cell development22, whereas in the myeloid lineage it is essential for erythroid differentiation23. Thus, ZBTB7A mutations may contribute to the block of differentiation in AML t(8;21).

The favourable prognostic relevance of high ZBTB7A expression in CN-AML, which accounts for half of all AML patients, may point towards a more general tumour suppressor role of ZBTB7A in myeloid leukaemia. In particular, the anti-proliferative properties of ZBTB7A may slow down disease progression. High ZBTB7A expression as a favourable prognostic marker has been reported also in colorectal cancer10, consistent with a clinicobiological role of ZBTB7A across malignancies of multiple tissue origins. Given that somatic mutations of ZBTB7A seem to be absent or rare in CN-AML, other mechanisms, including epigenetic changes or alterations of upstream regulators, may lead to inactivation or downregulation of ZBTB7A.

Our discovery of frequent ZBTB7A mutations in AML with t(8;21) translocation, one of the most common translocations in AML and the first balanced translocation identified in leukaemia1, demonstrates that the mutational landscape of AML is still not fully understood. Further studies will be required to unravel the mechanism underlying leukaemogenic cooperativity between mutated ZBTB7A and the RUNX1/RUNX1T1 fusion gene.

Methods

Patients

AML samples were collected within the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) at the partner sites Munich and Dresden. Patients were treated according to the protocols of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group (AMLCG) or Study Alliance Leukemia (SAL) multicentre clinical trials. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating centres. Informed consent was received in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sequencing

Exome sequencing (mean coverage: 87x; range 80–90x) was performed on a HiSeq 2000 Instrument (Illumina), using the SureSelect Human All Exon V5 kit (Agilent). Pretreatment blood or bone marrow specimens from 56 AML patients with t(8;21) translocation were sequenced using Haloplex custom amplicons (Agilent) and a HiSeq 1500 instrument (Illumina). Target sequence included the entire open-reading frame of ZBTB7A in addition to 45 leukaemia-related genes or mutational hotspots (Supplementary Table 3). Variant calling was performed as described previously24. Sanger sequencing of PCR-amplified genomic DNA was carried out using a 3500xL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Sequencing of messenger RNA was performed using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation protocol, followed by sequencing on a HiSeq 2000 Instrument (Illumina). RNA sequence reads were aligned to the human genome (hg19) using STAR25 (version 2.4.1b). Reads per gene were counted using HTseq26 (version 0.6.1) with intersection-strict mode and normalized for the total number of reads per sample.

Structural modelling

Suitable templates for the modelling were searched with HHPRED27, using the zinc-finger domain of ZBTB7A as input sequence. The highest scoring homologue, for which a structure of a DNA complex is available, was the Wilms tumour suppressor protein28 (PDB accession code 2J9P, E-value 4.8E–29, P-value 1.3E–30). The model for ZBTB7A was generated on the basis of 2J9P using MODELLER29. Importantly, 2J9P also contains an arginine at the equivalent position of ZBTB7A's R402, allowing us to model the function of R402 as major groove binder with confidence.

Plasmids

The pcDNA3.1-His-ZBTB7A expression construct was a gift from Takahiro Maeda (Boston). ZBTB7A A175fs, R377X, R402C and R402H mutant plasmids were generated using the QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. ZBTB7A wild type and mutants were subcloned into pMSCV-IRES-YFP (pMIY), using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech) and EcoRI restriction sites. The pMSCV-IRES-GFP(pMIG)-RUNX1/RUNX1T1 plasmid was provided by Christian Buske (Ulm).

DNA pull-down

HEK293T cells (DSMZ no.: ACC 635) were transfected with pcDNA3.1 His-Xpress-ZBTB7A (wild type or mutant). After 24 h, protein was extracted using lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail). For each reaction, 20 μl protein lysate was incubated in binding buffer (PBS supplemented with 150 mM NaCl resulting in a total salt concentration of nearly 300 mM, 0.1% NP40, 1 mM ETDA) with 10 pM biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides that contain either the ZBTB7A consensus binding motif (POK WT; 5′-GGTTAAAAGACCCCTCCCCGAATTCGGATC-3′) or a mutant thereof (POK mut; 5′-GGTTAAAATTTTTCTCCCCGAATTCGGATC-3′). After 1 h of incubation at 4 °C, 10 μl streptavidin agarose beads (Sigma Aldrich) was added to each reaction and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times with binding buffer and resupended in 10 μl Laemmli buffer for subsequent western blot analysis. ZBTB7A protein was detected using an antibody against the Xpress tag (1:5,000 dilution, clone R910-25; Life Technologies) and secondary goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1:10,000 dilution, clone sc-2060; Santa Cruz). The uncropped western blot scan underlying Fig. 2c is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Reporter gene assay

HEK293T cells (DSMZ no.: ACC 635) were co-transfected with pcDNA3.1-His-ZBTB7A (wild type or mutant), pGL2-p19ARF-Luc (gift from Takahiro Maeda, Boston) as well as pRL-CMV (Renilla luciferase; Promega) using Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFischer). After 24 h, cells were lysed; Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was measured with the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Three independent experiments were each performed in triplicates.

Western blot

HEK293T cells (DSMZ no.: ACC 635) were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFischer) with pcDNA3.1-His-ZBTB7A (wild type or mutant). After 24 h, protein was either extracted by multiple freeze–thaw cycles in lysis buffer (600 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.8, 20% Glycerol, cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail) or using the Qproteome Nuclear Protein Kit (Qiagen) for the analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions. From archived patient bone marrow samples, protein was isolated using the AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and protein transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Hybond PTM, Amersham Pharmacia biotech), immunoblots were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk, probed with anti-human Pokemon (ZBTB7A) purified antibody (1:5,000 dilution, clone: 13E9; eBioscience) and secondary anti-Armenian hamster IgG-HRP (1:10,000 dilution, clone: sc-2443; Santa Cruz). As loading control immunoblots were incubated with rabbit anti-actin (1:5,000 dilution, clone: sc-1616- R; Santa Cruz) and secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:10,000 dilution, clone: sc-2030; Santa Cruz). For analysis of the nuclear and cytoplasmic ZBTB7A protein fractions, we used mouse anti-Xpress tag (1:5,000 dilution, clone R910-25, Life Technologies) and secondary goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1:10,000 dilution, clone: sc-2060; Santa Cruz). Mouse anti-GAPDH (1:10,000 dilution, clone: sc-32233; Santa Cruz) served as loading control for the cytoplasmic protein fraction. Proteins were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham, GE Healthcare).

Immunofluorescence staining

U2OS human osteosarcoma cells (ATTC no.: HTB-96) were grown on coverslips and transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-His-ZBTB7A wild type and mutant constructs using PoliFect (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Cells were fixed 48 h post transfection using PBS 2% formaldehyde (37% stock solution; Merck Schuchardt) for 10 min, permeabilized with PBS 0.5% Triton X-100 (Carl Roth) for 10 min and blocked for 1 h with PBS 2% bovine serum albumin (Albumin Fraction V, AppliChem). Cells were then incubated with polyclonal rabbit His-probe (H-15) antibody (1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz) for 1 h. After extensive washing with PBS 0.1% Tween 20 (Carl Roth), secondary antibody incubation was performed for 1 h with goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), F(ab′)2 fragment Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate (1:500 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology). Counterstaining was performed using NucBlue Reagent and ActinGreen 488 ReadyProbes Reagent (Life Technologies; 2 drops per ml) at room temperature for 20 min. Coverslips were mounted using fluorescence mounting medium (DAKO). Specimens were analysed using a confocal fluorescence laser scanning system (TCS SP5 II; Leica). For image acquisition and processing, the LAS AF Lite Software (Leica) was used.

Retroviral transduction

Retroviral transduction of Kasumi-1 cells (DSMZ no.: ACC 220) was accomplished as outlined previously30. In brief, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pMSCV-IRES-YFP (pMIY) vectors containing either wild-type or mutant (A175fs, R402C) ZBTB7A and packaging plasmids. After 48 h, the cell culture supernatant was collected, sterile filtered and used for viral loading of RetroNectin (Takara Clontech)-coated plates. A total of 3 × 105 Kasumi-1 cells were transduced per well. The percentage of YFP-positive cells was assessed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Three independent experiments were each performed in duplicates.

Colony-forming cell assay

For in vitro CFC assays, bone marrow cells were collected from the femur and pelvic girdle of wild-type mice (C57BL/6X129/J). Lineage-negative haematopoietic progenitors were isolated using magnetic separation (MACS, murine lineage depletion kit, Miltenyi biotech). Retrovirally transduced cells were sorted for GFP/YFP and were plated in 1% myeloid-conditioned methylcellulose containing Iscove's modified Dulbecco medium-based Methocult (Methocult M3434; StemCell Technologies) at a concentration of 500 cells per ml. Single-cell suspensions of colonies were serially replated at the same concentration until the exhaustion of cell growth. Three independent experiments were each performed in duplicates.

Analysis of clinical and gene expression data

Clinical relevance of ZBTB7A mutations or expression levels was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test. Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables, while Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney U-test was applied for continuous variables. All patients included in this analysis were treated intensively with curative intent according to the AMLCG protocols. Gene expression profiling was performed on 215 adult patients with cytogenetically normal AML, using Affymetrix Human Genome (HG) U133A/B (n=155) and HG U133Plus2.0 microarrays (n=60). The RMA method was used for data normalization, and probe set summarization utilized custom chip definition files based on the GeneAnnot database (version 2.2.0). Probe set GC19M004001_at was used to determine ZBTB7A expression levels. High ZBTB7A expression was defined as the highest (4th) quartile of expression values observed in CN-AML patients. Patients with ZBTB7A expression levels in the 1st to 3rd quartile were classified as having low expression. The patients analysed here represent a subset of the previously published data set GSE37642. Validation of the results was done using data sets from the Haemato Oncology Foundation for Adults in the Netherlands (HOVON) study group (GSE14468 and GSE1159)16,17.

Data availability

Data referenced in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus database with the accession codes GSE37642, GSE14468 and GSE1159. The next-generation sequencing data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (P.A.G). The data are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy or consent. Explicit consent to deposit raw-sequencing data was not obtained from the patients, many samples were collected >10 years ago. Thus, the vast majority of patients cannot be asked to provide their consent for deposit of their comprehensive genetic data.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Hartmann, L. et al. ZBTB7A mutations in acute myeloid leukaemia with t(8;21) translocation. Nat. Commun. 7:11733 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11733 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-9 and Supplementary Tables 1-5.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants and recruiting centres of the AMLCG and SAL trials. This work was supported by a grant to P.A.G. and H.B. from the Wilhelm-Sander-Stiftung (2014.162.1). K.H.M, K.S., P.A.G., W.H., K.-P.H. and H.B. acknowledge support from the German Research Council (DFG) within the Collaborative Research Centre (SFB) 1243 ‘Cancer Evolution' (projects A06, A07, A08, A10 and Z02). We thank Christina Schreck and Robert A.J. Oostendorp for providing murine bone marrow.

Footnotes

Author contributions L.H. and. P.A.G. conceived and designed the experiments. L.H., S.D., S.O., G.L., K.R., K.B., C.P., L.C.-W. and S.K. performed the experiments. L.H., S.O., K.R., T.H., S.A.B., K.H.M. and S.V. analysed the data. S.V. and A.G. provided the bioinformatics support. H.B. and S.W. managed the sequencing platforms. K.B., E.Z., N.P.K., S.S., J.B., S.K.B., K.S., J.M.M., F.S. and C.T. characterized the patient samples. M.C.S., J.B., W.E.B., T.B., B.J.W. and W.H. coordinated the AMLCG clinical trials. K.-P.H. performed the structural modelling. P.A.G., C.W. and K.S. supervised the project. L.H. and P.A.G. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Rowley J. D. Identificaton of a translocation with quinacrine fluorescence in a patient with acute leukemia. Ann. Genet. 16, 109–112 (1973). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson P. et al. Identification of breakpoints in t(8;21) acute myelogenous leukemia and isolation of a fusion transcript, AML1/ETO, with similarity to Drosophila segmentation gene, runt. Blood 80, 1825–1831 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardiman J. W. et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood 114, 937–951 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades K. L. et al. Analysis of the role of AML1-ETO in leukemogenesis, using an inducible transgenic mouse model. Blood 96, 2108–2115 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schessl C. et al. The AML1-ETO fusion gene and the FLT3 length mutation collaborate in inducing acute leukemia in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2159–2168 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieger M. et al. AML1-ETO inhibits maturation of multiple lymphohematopoietic lineages and induces myeloblast transformation in synergy with ICSBP deficiency. J. Exp. Med. 196, 1227–1240 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. et al. AML1-ETO expression is directly involved in the development of acute myeloid leukemia in the presence of additional mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10398–10403 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M. et al. Expression of a conditional AML1-ETO oncogene bypasses embryonic lethality and establishes a murine model of human t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 1, 63–74 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunardi A., Guarnerio J., Wang G., Maeda T. & Pandolfi P. P. Role of LRF/Pokemon in lineage fate decisions. Blood 121, 2845–2853 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. S. et al. ZBTB7A acts as a tumor suppressor through the transcriptional repression of glycolysis. Genes Dev. 28, 1917–1928 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costoya J. A. Functional analysis of the role of POK transcriptional repressors. Brief Funct. Genomic Proteomic 6, 8–18 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D. J. et al. FBI-1, a factor that binds to the HIV-1 inducer of short transcripts (IST), is a POZ domain protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 1251–1262 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micol J. B. et al. Frequent ASXL2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1 chromosomal translocations. Blood 124, 1445–1449 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T. et al. Role of the proto-oncogene Pokemon in cellular transformation and ARF repression. Nature 433, 278–285 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendergrast P. S., Wang C., Hernandez N. & Huang S. FBI-1 can stimulate HIV-1 Tat activity and is targeted to a novel subnuclear domain that includes the Tat-P-TEFb-containing nuclear speckles. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 915–929 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valk P. J. et al. Prognostically useful gene-expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1617–1628 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters B. J. et al. Double CEBPA mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations, define a subgroup of acute myeloid leukemia with a distinctive gene expression profile that is uniquely associated with a favorable outcome. Blood 113, 3088–3091 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavallée V.-P. et al. RNA-sequencing analysis of core binding factor AML identifies recurrent ZBTB7A mutations and defines RUNX1-CBFA2T3 fusion signature. Blood, pii: blood-2016-03-703868 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jeon B. N. et al. Proto-oncogene FBI-1 (Pokemon/ZBTB7A) represses transcription of the tumor suppressor Rb gene via binding competition with Sp1 and recruitment of co-repressors. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33199–33210 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. et al. Zbtb7a suppresses prostate cancer through repression of a Sox9-dependent pathway for cellular senescence bypass and tumor invasion. Nat. Genet. 45, 739–746 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. S. et al. Somatic human ZBTB7A zinc finger mutations promote cancer progression. Oncogene, doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.371 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T. et al. Regulation of B versus T lymphoid lineage fate decision by the proto-oncogene LRF. Science 316, 860–866 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T. et al. LRF is an essential downstream target of GATA1 in erythroid development and regulates BIM-dependent apoptosis. Dev. Cell 17, 527–540 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold T. et al. Isolated trisomy 13 defines a homogeneous AML subgroup with high frequency of mutations in spliceosome genes and poor prognosis. Blood 124, 1304–1311 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P. T. & Huber W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand A., Remmert M., Biegert A. & Soding J. Fast and accurate automatic structure prediction with HHpred. Proteins 77, (Suppl 9): 128–132 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll R. et al. Structure of the Wilms tumor suppressor protein zinc finger domain bound to DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 1227–1245 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb B. & Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol. Biol. 1137, 1–15 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann C. et al. Activating c-KIT mutations confer oncogenic cooperativity and rescue RUNX1/ETO-induced DNA damage and apoptosis in human primary CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors. Leukaemia 29, 279–289 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. et al. IBS: an illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences. Bioinformatics 31, 3359–3361 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-9 and Supplementary Tables 1-5.

Data Availability Statement

Data referenced in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus database with the accession codes GSE37642, GSE14468 and GSE1159. The next-generation sequencing data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (P.A.G). The data are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy or consent. Explicit consent to deposit raw-sequencing data was not obtained from the patients, many samples were collected >10 years ago. Thus, the vast majority of patients cannot be asked to provide their consent for deposit of their comprehensive genetic data.