Abstract

Past evidence has documented that attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation are related to sexual behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. This study extends prior research by longitudinally testing these associations across racial/ethnic groups and investigating whether culturally relevant variations within racial/ethnic minority groups, such as skin tone (i.e., lightness/darkness of skin color), are linked to attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation and sex. Drawing on family and public health literatures and theories, as well as burgeoning skin tone literature, it was hypothesized that more positive attitudes toward marriage and negative attitudes toward cohabitation would be associated with less risky sex, and that links differed for lighter and darker skin individuals. The sample included 6872 respondents (49.6 % female; 70.0 % White; 15.8 % African American; 3.3 % Asian; 10.9 % Hispanic) from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. The results revealed that marital attitudes had a significantly stronger dampening effect on risky sexual behavior of lighter skin African Americans and Asians compared with their darker skin counterparts. Skin tone also directly predicted number of partners and concurrent partners among African American males and Asian females. We discuss theoretical and practical implications of these findings for adolescence and young adulthood.

Keywords: Marriage, Cohabitation, Sexual behavior, Skin tone, Adolescents, Young adults

Introduction

Risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults has been a major public health concern, due to its prevalence and negative consequences for health and development (Fergus et al. 2007; Paik 2010). Engagement in risky sexual behavior, including having multiple sexual partners and concurrent sexual partners, increases risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unintended pregnancies, and cervical and other cancers (Adimora et al. 2007; Chandra et al. 2011; O'Donnell et al. 2006). A large body of empirical research has documented correlates and predictors of sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults. Research has linked family (e.g., parenting and family structure; Landor et al. 2011; Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfand 2008) and individual factors (e.g., religiosity, intelligence; Halpern et al. 2000; Landor and Simons 2014) with risky sexual behavior. Studies have also begun to use a family life cycle perspective to investigate how behaviors, including sexual behavior, may be linked to marriage and cohabitation attitudes. Recent cross-sectional work has shown that attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation may be associated with sexual behavior patterns (Carroll et al. 2007; Willoughby and Carroll 2010). Understanding the impact of marriage and cohabitation attitudes on decisions about sex is particularly important because this work may help scholars to better understand how such beliefs shape and alter individual and relational behaviors during a critical period for individual and relational development (Arnett and Tanner 2006). Further, examining what early factors influence risky sex can lead to better prevention and intervention strategies that encourage healthy sexual decision making.

Despite recent cross-sectional investigations of the implications of marriage and cohabitation attitudes on sex, several limitations remain in the current literature. First, less attention has been directed toward understanding whether attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation formed in late adolescence predict subsequent sexual behavior in young adulthood, thereby limiting our understanding of the long-term implications of attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation on later decisions about sex. Second, the majority of studies have been conducted with White samples; thus, little is known about these relationships across other racial/ethnic groups. Although some scholars document differences in marriage and cohabitation experiences across racial/ethnic groups, with African Americans much less likely to marry and more likely to cohabit than Whites (Chambers and Kravitz 2011; Kennedy and Bumpass 2008), no research has investigated whether the links between marriage and cohabitation attitudes and sexual behavior vary across racial/ethnic minority groups. The current study also assesses marriage and cohabitation attitudes across racial/ethnic groups. Third, this study incorporates the marital horizon theory (Carroll et al. 2007) and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) to offer predictions on how attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation may be associated with subsequent risky sexual behavior across racial/ethnic groups. Lastly, past research has not included considerations of sociocultural factors that could be pivotal in shaping individuals’ attitudes about marriage and cohabitation and behaviors. Specifically, colorism is one such sociocultural factor. This form of discrimination is concerned with skin tone (i.e., lightness/darkness of skin color), rather than race or ethnicity.

Research suggests that skin tone functions as “epidermic capital” providing lighter skin individuals with special privileges and advantages not available to their darker skin counterparts (Herring et al. 2004). Moreover, studies have documented that variations in skin tone play a significant role in shaping social stratification and behavior patterns in racial/ethnic minority groups (Burton et al. 2010; Landor et al. 2013), with associations found between romantic relationship experiences such as marriage/marriage market and spousal status (e.g., higher spousal educational attainment and income) as well as risk behaviors, and skin tone. The lack of attention directed toward skin tone differences within racial/ethnic minority groups is an important gap in the literature as such analysis is often overshadowed by more general discussions of racial differences. This study moves beyond a traditional approach that solely focuses on racial differences or ignores socio-cultural factors all together to shed light on skin tone as a factor that may be associated with the relationship and health outcomes of adolescents and young adults.

The Connection Between Attitudes and Sex: Drawing from the Marital Horizon Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior

The majority of studies on correlates and predictors of sexual behavior have failed to provide a theoretically-driven framework for understanding why specific factors may affect sexual behavior (Christopher and Sprecher 2000). The present study draws on both theory and empirical research from family and public health literatures to investigate whether marriage and cohabitation attitudes are longitudinally associated with risky sexual behavior. In particular, we use the marital horizon theory and the theory of planned behavior as guides for conceptualizing these relationships. In recent work, family scholars Carroll et al. (2007) developed the marital horizon theory to explain how an individual's orientation toward marriage (e.g., beliefs, desires, and expectations) plays a role in shaping their behavior. The theory proposes that individuals who place high value on marriage or who anticipate marriage in their future are more likely to believe that risky behaviors, such as risky sexual behaviors, are incompatible with marriage and married life (anticipatory socialization; Merton 1957). Therefore, they would be less experimental in their behaviors.

There is evidence consistent with this hypothesis. Clark et al. (2009), in a study of 1087 youth, found a significant inverse association between marriage attitudes (e.g., desire to marry sooner rather than later) and risky sexual behavior, suggesting that adolescents, particularly women, are engaging in behavior that is consistent with their future life course aspirations. In addition, cross-sectional studies of predominately White emerging adults between the ages of 18 and 26 years old found attitudes toward marriage to be associated with behaviors such as substance use and sexual activity (Carroll et al., 2007; Willoughby and Dworkin 2009). Cohabitation attitudes may also be related to sexual behavior. More specifically, among predominately white samples of non-married and non-cohabiting emerging adults, endorsement of cohabitation was found to be positively associated with risky sexual behavior (Manning et al. 2007; Willoughby and Carroll 2010). As an explanation for this association, scholars suggest that although young people may not expect to cohabit with their sexual partners, their sexual experiences may be heightened by their interest in and attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation (Manning et al. 2007). To this end, more endorsement of cohabitation may increase one's likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behavior.

Furthermore, the marital horizon theory rests on some basic tenets of the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991). One key principle of the theory of planned behavior is that current attitudes (e.g., beliefs, desires, and expectations) and intentions are the best predictors of future behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). There is recent empirical evidence, consistent with these propositions, relative to processes of interest here. Waller and McLanahan (2005), for example, found expectations to marry to be the strongest predictor of future marriage. Lichter et al. (2004) found that unmarried women who desired to marry were four times more likely to have married 4 years later than women who did not desire to marry. Similarly, positive attitudes about cohabitation predicted later cohabitation (Cunningham and Thornton 2005). Based on these theories and prior empirical work, we hypothesize that more positive attitudes toward marriage and negative attitudes toward cohabitation will be longitudinally associated with less risky sexual behavior.

Perspectives of Skin Tone and Colorism: Linking Skin Tone, Attitudes, and Risky Sexual Behavior

Scholars have long argued that one of the most enduring legacies of slavery and white supremacy in the US is a racial stratification system that not only privileges Whites over Blacks and other racial/ethnic minority groups, but also privileges individuals with lighter skin tone over those with darker skin tone (Hunter 1998). Although colorism is similar to racial stereotyping and prejudice, it is distinctly different because its focus is on the physical characteristics of individuals within racial/ethnic groups. Literature on skin tone among racial/ethnic minority groups (i.e., African Americans, Hispanics, Asians) has consistently shown that darker skin individuals are perceived, evaluated and treated more negatively than lighter skin individuals because darker skin more closely represents the cultural stereotypes (e.g., aggressive, poor, unattractive, lazy), mostly negative, that are associated with people of color (Hunter 2007; Maddox 2004; Rondilla and Spickard 2007). A number of empirical studies and autobiographical accounts show a significant link between skin tone and life outcomes, including romantic relationship experiences. Lighter skin individuals are rated more favorably and receive more advantages compared to their darker skin peers (Bond and Cash 1992; Landor et al. 2013; Robinson and Ward 1995). For example, lighter skin individuals achieve higher levels of personal income, occupational prestige, educational attainment, and report more positive psychological outcomes, even after accounting for family characteristics (Keith and Herring 1991; Thompson and Keith 2001). These findings generally hold within and across racial/ethnic minority groups (Allen et al. 2000).

Existing literature on skin tone has also shown associations between skin tone and the marriage market and mate selection. Lighter skin individuals are more likely to marry, to marry sooner, and to have higher status spouses (Edwards et al. 2004; Udry et al. 1971) as individuals generally prefer mates with lighter skin tone (Bond and Cash 1992; Robinson and Ward 1995). Past research indicates that marriage is less common among darker skin women (Bodenhorn 2006). In particular, Hamilton et al. (2009), in a study of 329 young black women found that light skin tone was associated with approximately a 15 % greater probability of marriage. In other studies including focus groups of Black women, evidence suggests that darker skin individuals may be losing hope that committed relationships and marriage are attainable (Boylorn 2012; Ferdinand 2015; Golden 2007; Wilder and Cain 2011) given the relationship between skin tone and perceptions of beauty. For example, a participant in a recent qualitative study illustrated this point stating “None of the boys wanted to marry me because I was too dark and they were already asking me “you know your children are going to come out really, really dark and that's not good.” But my light skinned friend got married to a different boy every day. But, I didn't because I wasn't light enough, and that really hurt my feelings, and to this day, it still brings me back to the idea that I'm not good enough” (Awad et al. 2014, p. 550). Assuming darker skin individuals are aware of social preferences for lighter skin, darker skin individuals as compared to lighter skin individuals, may anticipate fewer prospects for mate selection and marriage and, in turn, view marriage as a less attainable option.

Studies have shown that lighter skin individuals are also less likely to participate in risk behavior such as criminal activity given the advantages that accrue to lighter skin, resulting in more risk adverse activities (Gyimah-Brempong and Price 2006). Though scholars have devoted efforts for decades to identifying correlates and predictors of risky sexual behaviors, researchers have overlooked one potentially salient factor among racial/ethnic minority groups: skin tone. Similar to its link with other life outcomes and for similar reasons, darker skin individuals may be more likely to engage in risk activities such as risky sexual behavior. Thus, skin tone may not only be a selection factor for romantic relationship experiences, but skin tone may also be associated with risky sexual behavior choices. Given the statistics on rates of risky sexual behaviors and subsequent outcomes associated with risky sex among young adults from racial/ethnic minority groups (Halpern et al. 2004), examining a potential link between skin tone and risky sexual behaviors is important.

Although a body of research suggests that lighter and darker skin individuals may have different romantic relationship and risky behavior experiences, research examining the potential impact of skin tone on how attitudes regarding marriage and cohabitation influence risky sexual behavior is limited. Scholars suggest that the demographic shifts in racial/ethnic group composition in the United States, as studies project the majority population will be from minority groups representing an array of skin complexion over the next few decades (Bonilla-Silva 2002), may be sustaining or exacerbating the significance of skin tone, therefore it is critical to investigate and understand the social role skin tone may play in the lives of some individuals.

Marriage and Cohabitation Attitudes

Most young Americans view marriage as important and expect to marry in the future (Crissey 2005). Over three-fourths (76 %) of adolescents probably or definitely expect to marry and most college students consider marriage as an important life goal (Carroll et al. 2007). Trend data on cohabitation show a steady increase in endorsement of cohabitation over the past few decades (Raley 2000; Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001). Nearly one-third of adolescents probably or definitely expect to cohabit (Manning et al. 2007). Other work reports similar findings with half of adolescents holding positive attitudes toward cohabitation (Martin et al. 2003). Moreover, these expectations about marriage and cohabitation are usually fulfilled. Bramlett and Mosher (2002) estimated that 81 % of non-Hispanic White women, 77 % of Hispanic women, and 52 % of non-Hispanic African American women will marry by age 30. Kennedy and Bumpass's (2008) study of US women showed that 38 % of 19–24 year old women and 58 % of 25–29 year old women reported having ever cohabited before marriage.

Though marriage and cohabitation attitudes have been documented, relatively few studies have examined attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation during the third decade of development, as most research has focused on adolescent samples (Manning et al. 2007; Martin et al. 2001). This is surprising given the extant literature on shifts in marriage and cohabitation patterns among young adults over the past half century. Additionally, previous work has mostly compared Whites and African Americans; we know less about whether these attitudes differ across other racial/ethnic groups. Such differences are important to identify, as attitudes are associated with individual and relational outcomes (Carroll et al. 2007). Knowledge about these attitudes may provide clues about future marriage and cohabitation norms.

Current Study and Hypotheses

The goal of this study was to examine the longitudinal links between attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation and risky sexual behavior across racial/ethnic groups. Grounded in the integration of family and public health theories and empirical findings described above, we hypothesize that more positive attitudes toward marriage and negative attitudes toward cohabitation will dampen risky sexual behavior because such risk is inconsistent with married life and future behaviors. Further, we employ perspectives on skin tone and colorism to test the moderating role of skin tone within racial/ethnic minority groups. We investigate whether the effect of attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation on risky sexual behavior will be stronger for lighter skin individuals compared to darker skin individuals because lighter skin individuals view marriage as a more attainable option. Darker skin individuals, on the other hand, may view marriage as such an unattainable option that more positive marriage attitudes do little to offset engagement in risky sexual behaviors. Therefore, we anticipate that skin tone may be shaping ideas about intimate relationships and marriage, thus impacting sexual behavior choices. Third, we examine whether skin tone was related to risky sexual behavior. Given that previous research has been suggestive of skin tone differences in risky behaviors, we hypothesized that lighter skin would be associated with less risky sexual behavior. Lastly, we assessed marriage and cohabitation attitudes among young adults across racial/ethnic minority groups and gender. Because there is less variation in skin tone among non-Hispanic Whites (Jablonski 2004) and because the large majority of skin tone research has been conducted on minority samples, we only test the direct and moderating effects of skin tone on racial/ethnic minority groups. We also controlled for religiosity at Wave III and Wave IV, respondent age, respondent education, current relationship status at Wave IV, and Family SES at Wave I, due to their significant associations with marriage and cohabitation attitudes and sexual behavior found in past literature (Halpern et al. 2006).

Methods

Data and Sample

The data for this study are from Waves III and IV of Add Health, a nationally representative, probability-based, longitudinal study of approximately 20,000 adolescents in the United States in grades 7–12 in 1994–1995 (see Harris et al. 2009 for design details). Follow-up in-home interviews occurred during 1995–1996 (Wave II), 2001–2002 (Wave III), and 2007–2008 (Wave IV). In-home interviews were conducted using laptop computers and computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI), given the sensitive nature of many of the topics discussed. Following respondents’ completion of surveys, interviewers were asked to rate respondents’ physical characteristics such as skin color, physical disability, and blindness based on their own observation. Respondents were between the ages of 18–26 years (M male age = 21.2 years; M female age = 21.1 years) at Wave III. By Wave IV, respondents were between the ages of 25–33 (M male age = 28.3 - years; M female age = 28.2 years). Additional details on the Add Health study can be found at www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

For this study, we limited the analyses to individuals who were interviewed at Waves III and IV, and had valid sampling weights (n = 14,800); identified as 100 percent heterosexual at Wave III (n = 10,914); were never married by the time of the Wave III interview (n = 9889); and had complete data on all study variables (n = 7122). A developmental perspective suggests that marriage and cohabitation attitudes often develop through early heterosexual romantic experiences, therefore, we included only heterosexual individuals (Crissey 2005). In addition, we included only non-Hispanic Whites (n = 3896), non-Hispanic African Americans (n = 1576), Hispanics, any race (n = 987), and non-Hispanic Asians (n = 413). The final analytical sample included 6872 respondents (3466 males; 3406 females).

Measures

Risky Sexual Behavior

We used two variables from Wave IV to measure young adult risky sexual behaviors. Number of sexual partners in the past 12 months was assessed using responses to the question “With how many male/female [opposite-sex] partners have you had sex in the past 12 months, even if only one time?” Responses ranged from 1 to 50. Respondents were also asked about instances of having concurrent sex partners in the past 12 months. The question asked “In the past 12 months, did you have sex with more than one partner at or around the same time?” Response categories ranged from 0 = no to 1 = yes. Each outcome variable was tested in a separate model.

Marriage and Cohabitation Attitudes

At Wave III, respondents reported their attitudes about marriage and cohabitation. We used four items assessing expectation of marriage, importance of marriage, desire to marry, and endorsement of cohabitation, based on the following questions. Expectation of marriage: “What do you think the chances are that you will be married in the next 10 years?” Responses ranged from 1 = almost certain to 5 = almost no chance. Importance of marriage: “How important is it to you to be married someday?” Responses ranged from 1 = very important to 4 = not at all important. Desire to marry: “How much do you agree or disagree with the statement”- “I would like to be married now?” Responses ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. Endorsement of cohabitation: “How much do you agree or disagree with the statement- It is all right for an unmarried couple to live together even if they aren't interested in considering marriage?” Responses ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. All items were reverse coded. Therefore, higher scores indicate more positive attitudes towards that specific item.

Skin Tone

At Wave III, respondents’ skin color was rated by the interviewers’ observations of the respondents’ complexions. Each interviewer was asked “What is the respondent's skin color?” Responses were 1 = black, 2 = dark brown, 3 = medium brown, 4 = light brown, and 5 = White. Although we recognize that this scale may not be optimal as it involves the subjective perception of the rater, it has been the predominant method of measuring skin tone. This measurement scheme is similar to other studies that have used objective ratings of skin color (Hunter 2002; Thompson and Keith 2001). This item was reverse coded so that higher scores indicate a darker skin color.

Covariates

We controlled for religiosity at Wave III and Wave IV, respondent age, respondent education, current relationship status at Wave IV, and Family SES at Wave I. Six items (at Wave III) and five items (at Wave IV) were used to measure religiosity, including measures of religious participation and commitment. Example questions respondents were asked included “How often have you attended church, synagogue, temple, mosque, or religious services in the past 12 months?” and “How important is your religious faith to you?” All items were standardized and summed to form a religiosity scale. Cronbach's α at Waves III and IV was .84 and .86, respectively. Similar to other studies using Add Health data (Crissey 2005; Halpern et al. 2001), parent's education served as a proxy for family socioeconomic status and consisted of the highest level of education attained by either parent/caregiver, whichever is greater. Respondent's age was included as a continuous measure. Respondent's education at Wave IV was assessed using the questions “What is the highest level of education that you have achieved to date?” with responses ranging from 1 = 8th grade or less to 13 = completed post baccalaureate professional education. Current relationship status was coded 0 = not in current relationship or 1 = in current relationship.

Statistical Analysis

We first examine the means and percentages of marriage and cohabitation attitudes and risky sexual behavior across race/ethnicity and gender. These findings provide new descriptive information. Next, we test for racial/ethnic differences in marriage and cohabitation attitudes and risky sexual behavior using ANOVA tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Given extensive research showing gender differences across all study variables (Manning et al. 2007; Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001), separate analyses were conducted for males and females. Third, hierarchical regressions were used to estimate models predicting number of sexual partners and concurrent sexual partners, stratified by race/ethnicity and gender and run separately for the 8 resulting subgroups. Hierarchical regressions models were used for our continuous outcome of number of sexual partners and hierarchical logistic regression models were used for our dichotomous outcome of concurrent sexual partner(s). Model 1 includes all control variables; Model 2 adds marriage and cohabitation attitudes to Model 1; Model 3 adds the skin tone variable to Model 2; Model 4 adds two-way interaction terms for marriage and cohabitation attitudes and skin tone to Model 3. Post hoc analyses were conducted using a simple slope test when interaction effects were present (Aiken and West 1991). We did not test for the direct and moderating effects of skin tone in the non-Hispanic White group because there was little skin tone variation among this group. In addition, all analyses used sampling weights and controlled for survey design using STATA 11.0 “svyset” commands (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for marriage and cohabitation attitudes and risky sexual behaviors by race/ethnicity and gender. Percentages are weighted, N's are not. Most respondents had strong expectations to marry. Means ranged from 3.76 to 4.13 for males and from 3.93 to 4.17 for females, suggesting a good chance or a 50–50 chance to marry in the next 10 years. Mean scores for importance of marriage were also high. The majority of males and females reported being married someday to be very important or somewhat important. The mean scores for desire to marry now, on the other hand, were relatively low. The mean scores for males ranged from 2.06 to 2.27 and 2.27 to 2.69 for females suggesting that most respondents neither agree or disagree or disagree somewhat about wanting to be married now (i.e., at the time of the interview). Lastly, most respondents neither agree or disagree or agree somewhat with the statement that it is all right for an unmarried couple to live together even if they are not considering marriage.

Table 1.

Mean score and percentage of marriage and cohabitation attitudes and sexual behavior, by gender and race

| Males |

Females |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 3466) |

Non- Hispanic White (n = 2040) |

Non- Hispanic African American (n = 682) |

Hispanic (n = 525) |

Non- Hispanic Asian (n = 219) |

Test statistic | Total (N = 3406) |

Non- Hispanic White (n = 1856) |

Non- Hispanic African American (n = 894) |

Hispanic (n = 462) |

Non- Hispanic Asian (n = 194) |

Test statistic | |

| Variable | Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

Mean (SE)/ % (n) |

||

| Marriage and cohabitation attitudes | ||||||||||||

| Marital expectation | 3.90 (.03) | 3.91 (.03) | 3.76 (.07) | 3.94 (.06) | 4.13 (.08) | F (3,3458) = 6.72** | 4.11 (.03) | 4.17 (.04) | 3.93 (.06) | 4.05 (.08) | 4.07 (.12) | F (3,3400) = 5.14** |

| Marital importance | 3.31 (.02) | 3.35 (.03) | 3.11 (.05) | 3.25 (.06) | 3.48 (.08) | F (3,3458) = 10.62** | 3.40 (.03) | 3.48 (.03) | 3.18 (.04) | 3.29 (.07) | 3.45 (.10) | F (3,3400) = 17.82** |

| Marital desire | 2.24 (.04) | 2.24 (.05) | 2.24 (.08) | 2.27 (.09) | 2.06 (.12) | F (3,3458) = 1.12 | 2.63 (.04) | 2.65 (.05) | 2.69 (.06) | 2.47 (.09) | 2.27 (.17) | F (3,3400) = 4.15** |

| Endorsement of cohabitation | 3.68 (.04) | 3.77 (.04) | 3.36 (.10) | 3.51 (.08) | 3.59 (.14) | F (3,3458) = 27.71** | 3.30 (.04) | 3.41 (.05) | 2.84 (.08) | 3.34 (.09) | 3.35 (.20) | F (3,3400) = 37.52** |

| Sexual behavior | ||||||||||||

| Number of sex intercourse partners | 1.86 (.07) | 1.68 (.07) | 2.89 (.19) | 1.77 (.12) | 1.45 (.13) | F (3,3458) = 44.89** | 1.27 (.05) | 1.23 (.05) | 1.42 (.11) | 1.34 (.20) | 1.21 (.09) | F (3,3400) = 1.40* |

| Concurrent sexual partner (A) | 18 % (637) | 15 % (305) | 32 % (216) | 20 % (93) | 11 % (23) | χ2 (n = 3462) = 17.69** | 9 % (319) | 8 % (148) | 12 % (117) | 10 % (37) | 11 % (17) | χ2 (n = 3404) = 1.64 |

N = 6872. (A) % represents emerging adults who reported having had a concurrent sexual partner in past 12 months

† p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Important racial/ethnic group differences in marriage and cohabitation attitudes are highlighted. Most notably, ANOVA analyses indicated significant racial/ethnic differences in all marriage and cohabitation attitudes for males and females, except for marital desire now among males. African American males (M = 3.76) and females (M = 3.93) reported the least positive expectations to marry and were least likely to view marriage as important for themselves (M = 3.11, M = 3.18, respectively), whereas Asian males (M = 4.13) and White females (M = 4.17) reported the most positive expectations of marriage and were most likely to view marriage as important for themselves (M = 3.48, M = 3.48, respectively). In terms of desire to marry now, there were no significant racial/ethnic group differences found among males, but Asian females (M = 2.27) had the lowest means compared to other racial groups and African American females (M = 2.69) had the highest means compared to other racial groups. In addition, White males (M = 3.77) and females (M = 3.41) had the highest mean endorsement of cohabitation without considering marriage, whereas African American males (M = 3.36) and females (M = 2.84) had the lowest mean endorsement. These results illustrate the heterogeneity of marriage and cohabitation attitudes across racial/ethnic groups and gender. In addition, we assessed the associations between marriage and cohabitation attitudes and skin tone among male and female racial/ethnic minority groups. Finding showed that darker skin was negatively associated with expectations to marry (−.12, p < .001 and −.10, p < .05, respectively) and viewing marriage as important (−.10, p < .01 and −.18, p < .001, respectively), even after controlling for other study variables (also see Landor under review).

This study also found that African American males and females reported the most sexual partners in the past 12 months (M = 2.89, M = 1.42, respectively), whereas Asian males and females reported the fewest (M = 1.45, M = 1.21, respectively). African American males were the most likely to have had a concurrent sexual partner in the past 12 months (32 %) and Asian males were the least likely (11 %). There were no racial/ethnic group differences in concurrent sexual partners in the past 12 months among females. The correlation matrix (table not shown) revealed no evidence of multicollinearity among independent variables.

Multivariate Results

Number of Sexual Partners

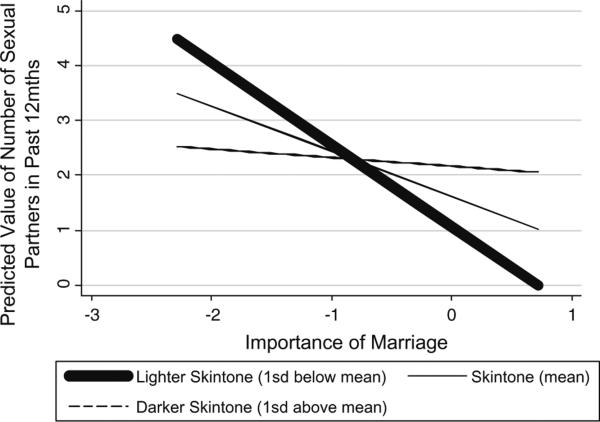

Table 2 includes results for number of sexual partners in the past 12 months. Significant associations between marriage and cohabitation attitudes and number of sexual partners were found among Asian females (higher importance of marriage predicted fewer sexual partners) and males (more endorsement of cohabitation without considering marriage predicted more sexual partners), even after controlling for religiosity, family SES, respondent age, respondent education, and current relationship status. Further, skin tone had a significant direct effect on number of sexual partners among African American males and Asian females. That is, darker skin African American males had more sexual partners (p < .01) and darker skin Asian females had fewer sexual partners (p < .01) compared with their lighter skin peers. We also tested whether the impact of marriage and cohabitation attitudes on number of sexual partners varied by an individual's skin tone. A significant two-way interaction was found among African American males (see Fig. 1). Positive attitudes toward marriage had a stronger dampening effect on risky sexual behaviors for lighter skin individuals than for darker skin individuals. Specifically, lighter skin males had fewer sexual partners than darker skin males when they thought marriage was important.

Table 2.

Multiple regression models assessing the influence of marriage and cohabitation attitudes and skin tone on number of sexual partners in past 12 months among males and females, stratified by race

| Variable | Non-Hispanic White |

Non-Hispanic African American |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) |

Coefficient (SE) |

||||||||||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | ||||||||

| Religiosity (wave III) | –.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.04) | –0.02 (.01) | –0.03 (.02) | –0.06 (.10) | –0.13 (.11) | –0.12 (.10) | –0.13 (.10) | –.09** (.04) | –.07** (.03) | –.07** (.03) |

| Religiosity (wave IV) | –0.01 (.04) | –0.03 (.04) | –.06** (.02) | –.06** (.03) | –.27** (.10) | –.23** (.10) | –.23* (.10) | –.21* (.09) | –0.05 (.05) | –0.04 (.04) | –0.04 (.05) |

| SES | 0.01 (.03) | 0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) | .23* (.12) | .23* (.11) | .25* (.12) | .26** (.10) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) |

| Age | –0.01 (.04) | –0.01 (.04) | –0.02 (.02) | –0.01 (.02) | 0.02 (.07) | 0.04 (.07) | 0.04 (.06) | 0.05 (.07) | –0.04 (.03) | –0.03 (.04) | –0.02 (.04) |

| Education | –0.02 (.03) | –0.03 (.03) | –0.04 (.02) | –0.05 (.03) | –0.03 (.10) | –0.03 (.10) | –0.02 (.09) | –0.03 (.09) | –0.02 (.05) | –0.03 (.06) | –0.03 (.05) |

| Current Relationship status | –.05† (.03) | –.16† (.03) | –0.01 (.02) | –0.01 (.02) | –0.03 (.09) | –0.03 (.09) | –0.03 (.08) | –0.02 (.08) | –0.03 (.03) | –0.03 (.03) | –0.03 (.03) |

| Marital importance | 0.01 (.03) | .05† (.02) | –0.13 (.09) | –0.11 (.08) | –.36* (.18) | –0.03 (.06) | –0.01 (.06) | ||||

| Marital expectations | –0.03 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.09 (.13) | –0.07 (.13) | 0.14 (.16) | –0.01 (.04) | –0.01 (.04) | ||||

| Marital desire | –0.07 (.03) | –0.03 (.03) | –0.03 (.09) | –0.04 (.10) | 0.25 (.17) | –0.07 (.07) | –0.07 (.07) | ||||

| Endorsement of cohabitation | 0.08 (.04) | –0.03 (.04) | 0.12 (.10) | 0.12 (.10) | 0.21 (.13) | 0.04 (.04) | 0.04 (.03) | ||||

| Skin Tone | .19** (.08) | .23** (.08) | 0.05 (.06) | ||||||||

| Marital importance* skin tone | .28** (.11) | ||||||||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Variable | Hispanic |

Non-Hispanic Asian |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) |

Coefficient (SE) |

|||||||||||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||||||

| Religiosity (wave III) | –0.01 (.07) | –0.05 (.09) | –0.04 (.08) | –0.04 (.10) | –0.01 (.09) | –0.02 (.10) | –0.01 (.07) | –0.09 (.09) | –0.08 (.12) | –0.03 (.02) | –0.03 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) |

| Religiosity (wave IV) | –0.01 (.08) | –0.01 (.08) | –0.01 (.08) | –.11* (.05) | –.10* (.08) | –.11* (.05) | –0.06 (.07) | –0.06 (.06) | –0.04 (.08) | –0.05 (.05) | –0.08 (.05) | –0.05 (.04) |

| SES | 0.06 (.05) | 0.05 (.04) | 0.05 (.05) | –0.03 (.05) | –0.04 (.05) | –0.03 (.05) | .13† (.06) | .09† (.05) | .09† (.05) | –0.04 (.04) | –0.04 (.03) | –0.04 (.03) |

| Age | 0.03 (.06) | 0.01 (.05) | 0.02 (.06) | –0.01 (.05) | –0.01 (.06) | –0.01 (.05) | 0.04 (.10) | 0.01 (.09) | 0.02 (.09) | 0.02 (.04) | 0.02 (.03) | 0.02 (.03) |

| Education | –0.05 (.05) | –0.02 (.05) | –0.02 (.06) | –0.04 (.06) | –0.05 (.06) | 0.06 (.06) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.04) | –0.04 (.04) | –0.04 (.03) |

| Current relationship status | –0.05 (.05) | –0.03 (.05) | –0.03 (.05) | –0.08 (.04) | –0.09 (.05) | –0.1 (.05) | –0.01 (.08) | –0.01 (.07) | –0.01 (.07) | –0.02 (.04) | –0.01 (.03) | –0.01 (.04) |

| Marital importance | –0.11 (.11) | –0.11 (.10) | –0.03 (.04) | –0.03 (.04) | 0.05 (.09) | 0.04 (.09) | –.15** (.05) | –.16** (.05) | ||||

| Marital expectations | 0.01 (.07) | 0.01 (.07) | 0.04 (.05) | 0.05 (.05) | 0.05 (.08) | 0.05 (.09) | 0.03 (.05) | 0.02 (.05) | ||||

| Marital desire | –0.05 (.05) | –0.05 (.05) | –0.01 (.05) | –0.01 (.05) | –0.03 (.09) | –0.01 (.09) | –0.02 (.04) | –0.01 (.03) | ||||

| Endorsement of cohabitation | 0.09 (.07) | 0.10 (.08) | 0.01 (.04) | 0.02 (.04) | .17** (.06) | .16* (.07) | 0.02 (.04) | 0.02 (.04) | ||||

| Skin tone | 0.08 (.07) | 0.06 (.07) | 0.07 (.09) | –.10** (.04) | ||||||||

| Marital importance × skin tone | ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

Results are standardized coefficients. Only significant interaction models are shown. Skin tone and the interactions of skin tone were not tested among the White male and female group given small variations in skin tone

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Fig. 1.

Skin tone of African American males as a moderator of associations between importance of marriage and predicted number of sexual partners

Concurrent Sexual Partner

Table 3 include results for concurrent sexual partners in the past 12 months. Significant associations between marriage and cohabitation attitudes and number of concurrent sexual partners were found among Hispanic and Asian females (higher desire to marry now had a 52 % increase in odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner and higher importance of marriage predicted reduced odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner, respectively) and non-Hispanic White and African American males (more endorsement of cohabitation without considering marriage predicted a 25 and a 24 % increase in odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner, respectively). Findings remained even after controlling for religiosity, family SES, respondent age, respondent education, and current relationship status. Furthermore, similar to results found for the number of sexual partners variable, skin tone predicted the odds of having a concurrent sexual partner for African American males and Asian females. Darker skin African American males had a 27 % increase in the odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner, whereas darker skin Asian females had a 79 % reduced odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner. Lastly, we tested whether the influence of marriage and cohabitation attitudes on the odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner varied by an individual's skin tone. Similar to interaction patterns found with number of sexual partners, significant two-way interactions were found among Asian males and African American females (figures not shown due to space limitations). Positive attitudes toward marriage had a stronger dampening effect on risky sexual behaviors for lighter skin individuals than for darker skin individuals. Lighter skin Asian males had reduced odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner compared with darker skin Asian males when they expected to marry and desired to marry now. Among African American females, lighter skin females had reduced odds of having had a concurrent sexual partner compared with darker skin females when they thought marriage was important.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models assessing the influence of marriage and cohabitation attitudes and skin tone on concurrent sexual partners in past 12 months among males and females, stratified by race

| Variable | Non-Hispanic White |

Non-Hispanic African American |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (CI) |

Odds ratio (CI) |

||||||||||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | ||||||||

| Religiosity (Wave III) | 0.98 (.92-1.03) | 0.99 (.94-1.04) | 1.00 (.92-1.07) | 1.00 (.93-1.07) | 0.99 (.94-1.05) | 1.00 (.94-1.06) | 1.00 (.94-1.05) | 0.95 (.89-1.02) | 0.97 (.89-1.07) | 0.97 (.94-1.05) | 0.98 (.95-1.06) |

| Religiosity (Wave IV) | 0.98 (.92-1.04) | 0.99 (.94-1.05) | 0.93 (.87-1.01) | 0.93 (.87-1.01) | .92* (.87-1.01) | 0.93 (.89-1.02) | 0.94 (.87-1.01) | 0.98 (.91-1.06) | 1.00 (.92-1.08) | 1.00 (.91-1.01) | 0.99 (.89-1.02) |

| SES | 1.02 (.85-1.22) | 1.00 (.83-1.20) | 0.98 (.70-1.40) | 0.96 (.68-1.36) | 1.09 (.80-1.52) | 1.11 (.79-1.58) | 1.12 (.81-1.58) | 0.99 (.72-1.36) | 0.99 (.73-1.35) | 0.99 (.74-1.58) | 1.02 (.73-1.58) |

| Age | 0.94 (.87-1.04) | 0.95 (.87-1.05) | 0.89 (.78-1.02) | 0.92 (.81-1.04) | 0.93 (.86-1.07) | 0.95 (.87-1.09) | 0.94 (.85-1.06) | 0.83 (.67-1.02) | 0.84 (.69-1.03) | 0.83 (.70-1.06) | 0.83 (.69-1.04) |

| Education | 0.98 (.90-1.06) | 0.97 (.90-1.05) | .85** (.78-.95) | .83** (.73-.93) | 0.98 (.85-1.14) | 0.98 (.85-1.14) | 0.99 (.86-1.14) | 1.00 (.87-1.16) | 1.00 (.89-1.16) | 1.00 (.86-1.14) | 0.99 (.86-1.15) |

| Current Relationship Status | .47** (.33-.66) | .47** (.33-.67) | .57** (.33-.97) | .53** (.31-.92) | 0.94 (.50-1.71) | 0.92 (.48-1.75) | 0.94 (.50-1.77) | 0.87 (.41-1.86) | 0.89 (.41-1.91) | 0.91 (.42-1.90) | 82 (.43-1.91) |

| Marital importance | 1.01 (.83-1.23) | 1.28 (.90-1.82) | 1.27 (.96-1.70) | 1.24 (.93-1.66) | .82† (.56-1.22) | .82† (.61-1.26) | .40* (.19-.84) | ||||

| Marital expectation | 1.02 (.87-1.22) | 1.02 (.74-1.38) | 0.95 (.76-1.19) | 0.97 (.77-1.23) | 1.08 (.82-1.42) | 1.08 (.83-1.39) | 1.70 (.83-1.38) | ||||

| Marital desire | 0.93 (.81-1.06) | .86† (.74-.99) | 0.95 (.82-1.10) | 0.94 (.82-1.10) | 0.90 (.72-1.13) | 0.90 (.72-1.15) | 1.04 (.73-1.15) | ||||

| Endorsement of cohabitation | 1.25*** (1.05-1.47) | 0.98 (.81-1.20) | 1.24* (1.01-1.52) | 1.25* (1.02-1.53) | 1.14 (.87-1.49) | 1.14 (.88-1.53) | 1.14 (.89-1.42) | ||||

| Skin tone | 1.27* (1.01-1.59) | 0.91 (.68-1.21) | 1.03 (.79-1.35) | ||||||||

| Marital expectation*skin tone | |||||||||||

| Marital desire*skin tone | |||||||||||

| Marital importance*skin tone | 1.49* (1.00-2.21) | ||||||||||

| Variable | Hispanic |

Non-Hispanic Asian |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (CI) |

Odds ratio (CI) |

|||||||||||||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||||||||

| Religiosity (wave III) | 1.03 (.88-1.19) | 1.03 (.89-1.19) | 1.04 (.89-1.20) | 1.05 (.92-1.21) | 1.04 (.92-1.19) | 1.04 (.89-1.20) | 1.02 (.83-1.35) | 1.05 (.87-1.39) | 1.04 (.84-1.42) | 1.06 (.84-1.42) | .87** (.77-.97) | .87* (.77-.99) | .84* (.84-.98) | No convergence |

| Religiosity (wave IV) | 0.90 (.78-1.06) | 0.89 (.78-1.06) | 0.89 (.77-1.04) | 0.94 (.78-1.14) | 0.97 (.80-1.17) | 0.96 (.77-1.04) | 0.93 (.78-1.04) | 0.92 (.79-1.07) | 0.93 (.79-1.09) | 0.95 (.79-1.09) | 1.35** (1.08-1.67) | 1.35** (.79-1.01) | 1.34** (.79-1.09) | |

| SES | 1.03 (.69-1.41) | 1.00 (.67-1.41) | 1.00 (.67-1.41) | 0.78 (.46-1.32) | 0.78 (.48-1.41) | 0.77 (.46-1.35) | 1.2 (.48-3.81) | 1.02 (.42-2.91) | 1.01 (.41-2.91) | 1.03 (.41-2.91) | 0.67 (.33-1.37) | 0.73 (.32-1.38) | 0.69 (.31-1.38) | |

| Age | 1.01 (.84-1.27) | 1.02 (.82-1.26) | 1.02 (.82-1.26) | 0.97 (.72-1.30) | 0.89 (.73-1.26) | 0.89 (.72-1.26) | .49* (.26-.95) | .56† (.31-1.02) | .55† (.46-1.08) | .61† (.34-1.06) | 1.18 (.77-1.81) | 1.11 (.78-1.82) | 1.10 (.77-1.81) | |

| Education | 1.00 (.86-1.19) | 1.03 (.87-1.20) | 1.03 (.87-1.19) | 0.86 (.72-1.03) | 0.9 (.73-1.20) | 0.91 (.73-1.19) | 1.09 (.75-1.27) | 0.97 (.78-1.18) | 1.00 (.80-1.25) | 1.06 (.87-1.29) | 1.30* (1.00-1.10) | 1.40* (1.06-1.85) | 1.40* (1.03-1.90) | |

| Current relationship status | 0.96 (.48-2.40) | 0.96 (.11-.59) | 0.96 (.11-.59) | 1.19 (.31-4.63) | 1.05 (.31-4.61) | 1.06 (.33-4.60) | 8.64 (.64-16.27) | 9.05 (.45-18.63) | 9.03 (.45-19.51) | 13.84 (.33-16.17) | 0.89 (.36-2.21) | 0.74 (.22-2.39) | 0.85 (.22-3.29) | |

| Marital importance | 0.92 (.48-1.55) | 0.92 (.48-1.55) | 0.85 (.44-1.64) | 0.86 (.48-1.64) | 3.73† (.88-15.83) | 3.66† (.89-14.87) | 6.54* (1.24-34.52) | .36** (.18-.70) | .23** (.10-.58) | |||||

| Marital expectation | 1.3 (1.01-1.18) | 1.3 (1.01-1.18) | 0.89 (.51-1.54) | 0.88 (.52-1.53) | .56† (.23-1.45) | .57† (.27-1.40) | .37† (.11-1.22) | 1.39 (.53-3.64) | 1.24 (.54-3.40) | |||||

| Marital desire | 1.00 (.78-1.58) | 1.11 (.78-1.58) | 1.52** (1.14-2.01) | 1.52** (1.16-2.01) | 1.14† (.66-1.98) | 1.17† (.66-2.09) | 1.00† (.60-1.60) | 0.89 (.58-1.37) | 1.1 (.66-1.34) | |||||

| Endorsement of cohabitation | 1.21 (.87-1.62) | 1.18 (.87-1.62) | 1.04 (.73-1.48) | 1.04 (.73-1.50) | 1.45 (.75-2.82) | 1.42 (.72-2.79) | 1.38 (.71-2.67) | 0.95 (.50-1.76) | 1.03 (.61-3.72) | |||||

| Skin tone | 1.02 (.69-1.48) | 1.09 (.53-2.23) | 1.2 (.64-2.27) | 1.44 (.75-2.74) | .21** (.09-.52) | |||||||||

| Marital expectation × skin tone | 2.06* (1.11-3.80) | |||||||||||||

| Marital desire × skin tone | 1.75** (1.32-2.32) | |||||||||||||

| Marital importance × skin tone | ||||||||||||||

Only significant interaction models are shown. Skin tone and the interactions of skin tone were not tested among the White male and female group given small variations in skin tone

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Discussion

The current study draws on the marital horizon theory and the theory of planned behavior, as well as burgeoning skin tone literature, to examine the relationship between attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation, skin tone, and risky sexual behavior among a national, contemporary sample of young adults across racial/ethnic groups and gender in the United States. Given the dramatic changes in marriage and cohabitation trends and high prevalence of risky sexual behavior among adolescent and young adults, research on whether attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation predict subsequent risky sexual behavior is needed as attitudes held in early life may shape or alter future behaviors and outcomes. Although there is some prior evidence that marriage and cohabitation attitudes are cross-sectionally linked to risk behaviors including risky sex, to our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate the long-term associations between marriage and cohabitation attitudes in late adolescence and subsequent risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. Importantly, though, this relationship was dependent on an individual's skin tone for some demographic groups.

Consistent with our hypotheses, more positive attitudes toward marriage had a stronger dampening effect on risky sexual behavior for lighter skin individuals compared to darker skin individuals. We attribute this partly to the possibility that lighter skin individuals may view marriage as a more attainable option. In contrast, more positive marital attitudes had a weaker dampening effect on risky sexual behavior for darker skin individuals than lighter skin individuals as darker skin individuals may view marriage as a less attainable option. Such findings are consistent with evidence suggesting that darker skin individuals, particularly women, may be losing hope that committed relationships and marriage are attainable (Awad et al. 2014; Boylorn 2012; Ferdinand 2015; Wilder and Cain 2011), therefore marriage and cohabitation attitudes do little to offset their engagement in risky sexual behavior. All these significant links emerged among specific racial/ethnic minority groups: African Americans and Asians. Together, our results contribute to the literature on marriage and cohabitation attitudes and sexual behavior by suggesting that it is not just individuals’ attitudes that contribute to their behavior, especially sexual behavior, but also how others perceive them in context. Recently, scholars have suggested that more research involving racial/ethnic minority groups should focus on salient intra-group differences such as skin tone (Burton et al. 2010; Landor et al. 2013). In response to this call, we provide evidence that associations between attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation and sexual behavior should be interpreted within the context of skin tone for some racial/ethnic minority groups.

The findings also documented direct associations between skin tone and risky sexual behavior for African American males and Asian females. Darker skin African American males reported more sexual partners and an increased likelihood of having a concurrent sexual partner compared with lighter skin peers, results consistent with past research showing a link between skin tone and risk behavior (Gyimah-Brempong and Price 2006). Work by Gyimah-Brempong and Price (2006) suggests that darker skin tone may be a social disadvantage that increases the likelihood of participating in risk behaviors. In contrast, skin tone was inversely related to risky sexual behaviors for Asian females in our analyses. Darker skin Asian females reported fewer partners and a lower likelihood of concurrency indicating that the influence of skin tone on Asian females does not fit the hypothesized model. It may be that for darker skin Asian females, not only does skin tone decrease their likelihood of romantic partnerships and marriage, as suggested by past research on dark skin and mate selection (Hamilton et al. 2009; Robinson and Ward 1995), it may also decrease their likelihood of sexual partnerships, resulting in less risky sexual behaviors. Future research should examine these associations more closely as no previous study has examined skin tone and sexuality. The findings are interesting because they provide preliminary evidence for the potential salience of an individual's skin tone for the risky sexual behavior of racial/ethnic minorities. This research may be critical to understanding how variations in skin tone impact health disparities. Further work is also needed to understand why our findings show a strong significant relationship between skin tone and sexual behavior among African American males and Asian females, but not their same race opposite-sex peers. Skin tone has been overlooked in risky behavior prevention and intervention programs; however, skin tone may play an important role in life course attitudes and behaviors. Further research is needed to investigate the complex nature of skin tone given the implications for STI and HIV prevention and intervention among racial/ethnic minority populations.

Another important goal of this study was to assess the marriage and cohabitation attitudes of a national, contemporary sample of young adults across racial/ethnic groups and gender in the United States. Consistent with adolescent and general population literature highlighting Americans’ continued valuing of marriage as an important institution (Lichter et al. 2004; Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001), our descriptive results showed that the majority of emerging adults express strong expectations to marry and view marriage as important for themselves. Thus, despite historical changes in marriage and cohabitation patterns, young people are not rejecting marriage, as some research has suggested. But most do not desire to be “married now.” This finding is consistent with contemporary marriage research indicating a delay in the age at first marriage (Cherlin 2010; Uecker and Stokes 2008). The findings also show that the majority of young adults endorse cohabitation without any interests in marriage, especially Whites, also consistent with extant literature based on more selected samples (i.e., adolescents, college students) (Manning et al. 2007; Willoughby and Carroll 2010). In addition, we found important racial/ethnic group differences in marriage and cohabitation attitudes. For example, African American young adults are least likely to expect to marry or to view marriage as important for themselves. We found no racial/ethnic group differences among males in their desire to marry now, yet African American females were more likely to desire to marry now compared with other racial/ethnic groups. This finding suggests that despite disproportionately low marriage rates among African American women (Chambers and Kravitz 2011), they still maintain a strong desire to marry now. Further, non-Hispanic Whites report the highest level of endorsement of cohabitation without any interests in marriage whereas African Americans report the lowest level of endorsement of cohabitation without any interests in marriage. However, African Americans are the most likely to cohabit (Phillips and Sweeney 2005). Quantitative and qualitative research suggests several explanations for this paradox among African Americans, such as economic constraints and a shortage of marriageable men (Edin and Kefalas 2011; Hurt et al. 2014; Smock et al. 2005). That is, although African Americans are less likely to endorse cohabitation, high unemployment and low earning potential among African American males reduce the pool of marriageable partners for African American women. Therefore, they are more likely to cohabit with little to no incentive to form a legal partnership—marriage. Because African American women place more emphasis on having economic supports in place prior to marriage, they may be more resistant to marrying someone who has few resources (Bulcroft and Bulcroft 1993; Raley 1996).

The current findings should be interpreted in the context of the study's limitation. First, we only included heterosexual individuals who had not been married by the Wave III interview in our sample. Therefore, we do not know whether the relationship between attitudes and sexual behavior would differ if an individual had been previously married. Second, the marriage attitude questions were only asked at Wave III of the Add Health survey, which prohibited us from testing whether changes in such attitudes over time are related to future behaviors. Third, we recognize that the interviewers’ ratings of respondents’ skin color may not be the optimal scale as it involves the subjective perception of the rater. However, it has been the predominant method of measuring skin tone. This measurement scheme is similar to other studies that have used objective ratings of skin color (e.g., Hunter 2002; Thompson and Keith 2001). Future studies should train interviewers to assess skin tone (see Landor et al. 2013). In addition, we did not have information on the skin tone of the interviewers, thus we could not include this as a control variable. Fourth, though it is possible that sexual behavior may also impact marriage and cohabitation attitudes, we were specifically interested in the longitudinal link in which attitudes precede behavior as suggested by this study's theoretical frameworks. Lastly, although our assessment of cohabitation is consistent with other studies (e.g., Willoughby and Carroll 2010, 2012) that have conceptualized a similar cohabitation measure as general endorsement of cohabitation, this measure could be interpreted as a type of cohabitation (i.e., living together without any interests in marriage) rather than a general cohabitation measure.

Despite these limitations, the present study is an important first step in linking skin tone to sexuality and in investigating the longitudinal impact of marriage and cohabitation attitudes on risky sexual behavior within the context of skin tone. The results provide important descriptive information on the marriage and cohabitation attitudes of a contemporary sample of young adults across racial/ethnic groups and gender in the United States. Our findings also have important implications for research and practice. For instance, awareness of sociocultural perceptions of skin tone by researchers and practitioners is critical. This sensitivity to the historic role of skin tone across racial/ethnic minority groups may provide valuable insight into ways in which skin tone informs and influences romantic relationship and risky behavior experiences resulting in a richer understanding of interpersonal relationships, which may be a starting point for working with individuals and couples from racial/ethnic minority groups. The results from this study also suggest potential directions for prevention and intervention programs focused on sexual health and intimate relationships. For example, in order to more accurately reflect the experiences of racial/ethnic minority group members, programs should not ignore skin tone as a stressor that may impact individuals’ interpersonal relationships and health. Not acknowledging the role of skin tone may be counterproductive to individuals of color and the people that serve them. Skin tone and its social implications (i.e., colorism) may be important factors to consider in programs involving sexual health and intimate relationships with racial/ethnic minority groups. Additionally, our findings have important theoretical implications. Theories related to the behavioral implications of marriage and cohabitation attitudes must be conditioned on other individual characteristics (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, skin tone) that are perceived by and assessed by others. Moreover, because marriage, cohabitation, and partnered sexual activity are dyadic behaviors, the implications of attitudes for behavioral prediction must account for the desires of other individuals as well as broader social context. Theoretical elaboration accounting for how individual differences may play out in dyadic and macro-contexts is needed for additional insight. Both quantitative and qualitative research approaches will be useful toward this end.

Conclusion

The current study builds upon previous family and public health theories and empirical research (Carroll et al. 2007; Willoughby and Carroll 2010), as well as burgeoning skin tone literature (Edwards et al. 2004; Hamilton et al. 2009) to (1) longitudinally test the association between adolescents’ marriage and cohabitation attitudes and young adults’ sexual behavior patterns across racial/ethnic groups and (2) investigate whether culturally relevant variations within racial/ethnic minority groups, such as skin tone (i.e., lightness/darkness of skin color), are linked to marriage and cohabitation attitudes and sex. Specifically, we examined whether more positive attitudes toward marriage and negative attitudes toward cohabitation would be longitudinally associated with less risky sex, and that links differed for lighter and darker skin individuals. We found that marital attitudes had a significantly stronger dampening effect on risky sexual behavior of lighter skin African Americans and Asians compared with their darker skin counterparts. Skin tone also directly predicted number of partners and concurrent partners among African American males and Asian females, even after controlling for demographic characteristics. The present study is important to the study of adolescence and young adulthood because it provides further evidence that skin tone may shape ideas about intimate relationships and marriage, thus impacting decisions about sexual behavior for some racial/ethnic minority groups.

This work provides several important contributions to the research literature on adolescents and young adults. First, and most importantly, our findings may help scholars to better understand how beliefs about marriage and cohabitation shape and alter individual and relational behaviors during a critical period for individual and relational development (Arnett and Tanner 2006). Understanding what early factors influence risky sexual behavior can lead to better prevention and intervention strategies that encourage healthy sexual decision making. Family scholars have argued that, given trends in the delay of marriage among young people, beliefs about marriage and cohabitation should become a more salient variable among developmental and family scholars. Second, our results shed light on skin tone as a factor that may be associated with the relationship and health outcomes of adolescents and young adults. Third, this research may also help to further delineate the mechanisms, specifically sociocultural mechanisms such as skin tone/colorism, through which attitudes about marriage and cohabitation early in an individual's development may impact later marital and relational outcomes. Lastly, our findings offer important implications for policy and prevention. We point to this research as an additional way to frame relational and marriage education materials. Rather than just focusing only on skill building, clinicians and educators could develop materials that promote “healthy” attitudes toward romantic relationship formation which may ultimately encourage healthy relationship development, healthy decision making, and healthy behavior. Our findings suggest that, if marriage and cohabitation attitudes place young people on trajectories toward or away from healthy marital formation and healthy developmental adjustment, scholars must consider the implications of young adulthood on later transitions (e.g., relationship formation and development in middle and late adulthood).

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by Grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Funding Halpern's effort was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant R01-HD57046; C. T. Halpern, Principal Investigator) and by the Carolina Population Center (Grant 5 R24 HD050924, awarded to the Carolina Population Center at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development).

Biography

Antoinette M. Landor, Ph.D. Dr. Antoinette Landor is an Assistant Professor of Human Development and Family Science at the University of Missouri-Columbia. She received a doctorate from the University of Georgia, and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on the impact of discrimination (based on skin tone and race) on family dynamics, mate selection, and health. In addition, she explores how family and sociocultural factors influence the sexual and romantic relationship behaviors of adolescents and young adults.

Carolyn Tucker Halpern, Ph.D. Dr. Carolyn Tucker Halper is a Professor of Maternal and Child Health in the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research aims to improve the understanding of healthy sexual development and the implications of adolescent experiences for developmental and demographic processes into adulthood.

Footnotes

Author Contributions AL conceived of the study, participated in its design and interpretation of the data, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript; CH participated in the interpretation of the data analyses and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest The authors report no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval Not applicable.

Informed Consent Not applicable.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenback VJ, Doherty IA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(12):2230–2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Allen W, Telles E, Hunter M. Skin color, income, and education: A comparison of African Americans and Mexican Americans. National Journal of Sociology. 2000;12:129–180. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Tanner JL. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Awad GH, Norwood C, Taylor DS, Martinez M, McClain S, Jones B, et al. Beauty and Body Image Concerns Among African American College Women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0095798414550864. doi:10.1177/0095798414550864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhorn H. Colorism, complexion homogamy, and household wealth: Some historical evidence. The American Economic Review. 2006;96(2):256–260. [Google Scholar]

- Bond S, Cash TF. Black beauty: Skin color and body images among African-American college women. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1992;22(11):874–888. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00930.x. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. We are all Americans!: The Latin Americanization of racial stratification in the USA. Race and Society. 2002;5:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boylorn RM. Dark-skinned love stories. International Review of Qualitative Research. 2012;5(3):299–309. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/irqr.2012.5.3.299. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. [March 3, 2013];Cohabition, marriage, divorce and remarriage in the United States (Series 22, No 2) 2002 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_022.pdf. [PubMed]

- Bulcroft RA, Bulcroft KA. Race differences in attitudinal and motivational factors in the decision to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;55:338–356. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Bonilla-Silva E, Ray V, Buckelew R, Freeman EH. Critical race theories, colorism, and the decade's research on families of color. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:440–459. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00712.x. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Willoughby B, Badger S, Nelson LJ, Barry C, Madsen SD. So close, yet so far away: The impact of varying marital horizons on emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2007;22(3):219–247. doi:10.1177/0743558407299697. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers AL, Kravitz A. Understanding the disproportionately low marriage rate among African Americans: An amalgam of sociological and psychological constraints. Family Relations. 2011;60(5):648–660. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00673.x. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Mosher WD, Copen C, Sionbean C. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data from the 2006-2008 National Survey of Family Growth (National Health Statistics Reports No. 36) National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher FS, Sprecher S. Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(4):999–1017. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00607.x. [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Poulin M, Kohler HP. Marital aspirations, sexual behaviors, and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(2):396–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissey SR. Race/ethnic differences in the marital expectations of adolescents: The role of romantic relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:697–709. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00163.x. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Thornton A. The influence of union transitions on White adults’ attitudes toward cohabitation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:710–720. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00164.x. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. University of California Press; Los Angeles: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K, Carter-Tellison K, Herring C. For richer, for poorer, whether dark or light: Skin tone, marital status, and spouse's earnings. University of Illinois Press; Urbana: 2004. pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand R. Skin tone and popular culture: My story as a dark skinned black woman. The Popular Culture Studies Journal. 2015;3:324–348. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH. Growth trajectories of sexual risk behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(6):1096–1101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074609. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.074609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; Reading, MA: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Golden M. Don't play in the sun: One woman's journey through the color complex. Anchor; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah-Brempong K, Price GN. Crime and punishment: And skin hue too? The American Economic Review. 2006;96(2):246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Joyner K, Udry JR, Suchindran C. Smart teens don't have sex (or kiss much either). Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26(3):213–225. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Oslak SG, Young ML, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex romantic relationships: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(10):1679–1685. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1679. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.10.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Waller MW, Spriggs A, Hallfors DD. Adolescent predictors of emerging adult sexual patterns. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:926. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.005. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Young ML, Waller MW, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Prevalence of partner violence in same-sex romantic and sexual relationships in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(2):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton D, Goldsmith AH, Darity W., Jr. Shedding “light” on marriage: The influence of skin shade on marriage for black females. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 2009;72(1):30–50. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2009.05.024. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, et al. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Herring C, Keith V, Horton HD. Skin deep: How race and complexion matter in the “color-blind” era. University of Illinois Press; Champaign, IL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter ML. Colorstruck: Skin color stratification in the lives of African American women. Sociological Inquiry. 1998;68(4):517–535. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.1998.tb00483.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter ML. If you're light you're alright: Light skin color as social capital for women of color. Gender and Society. 2002;16(2):175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. The persistent problem of colorism: Skin tone, status, and inequality. Sociology Compass. 2007;1(1):237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt TR, McElroy SE, Sheats KJ, Landor AM, Bryant CM. Married Black men's opinions as to why Black women are disproportionately single: A qualitative study. Personal Relationships. 2014;21(1):88–109. doi: 10.1111/pere.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski NG. The evolution of human skin and skin color. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2004;33:585–623. [Google Scholar]

- Keith VM, Herring C. Skin tone and stratification in the Black community. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(3):760–778. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Bumpass L. Cohabitation and children's living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1663–1692. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landor AM. Beyond Black and White but still in color: Examining skin tone and marriage attitudes and outcomes across racial/ethnic groups. under review.

- Landor AM, Simons LG. Why virginity pledges succeed or fail: The moderating effect of religious commitment versus religious participation. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23(6):1102–1113. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9769-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landor AM, Simons LG, Simons RL, Brody GH, Bryant CM, Gibbons FX, et al. Exploring the impact of skin tone on family dynamics and race-related outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27(5):817–826. doi: 10.1037/a0033883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landor AM, Simons LG, Simons RL, Brody GH, Gibbons FX. The influence of religion on African American adolescents’ risky sexual behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:296–309. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9598-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Batson CD, Brown JB. Welfare reform and marriage promotion: The marital expectations and desires of single and cohabiting mothers. Social Service Review. 2004;78(1):2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox KB. Perspectives on racial phenotypicality bias. Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;8:383–401. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. The changing institution of marriage: Adolescents’ expectation to cohabit and to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:559–575. [Google Scholar]

- Martin PD, Martin D, Martin M. Adolescent premarital sexual activity, cohabitation, and attitudes toward marriage. Adolescence. 2001;36:601–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PD, Specter G, Martin D, Martin M. Expressed attitudes of adolescents toward marriage and family life. Adolescence. 2003;38(150):359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social theory of science. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, Stueve A, Wilson-Simmons R, Dash K, Agronick G, JeanBapstiste V. Heterosexual risk behaviors among urban young adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26:87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Paik A. The contexts of sexual involvement and concurrent sexual partnerships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42:33–42. doi: 10.1363/4203310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, Sweeney MM. Premarital cohabitation and marital disruption among White, Black, and Mexican American women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(2):296–314. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK. A shortage of marriageable men? A note on the role of cohabitation in black–white differences in marriage rates. American Sociological Review. 1996;61(6):973–983. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK. Recent trends and differentials in marriage and cohabitation: The United Satates. In: Waite LJ, editor. The ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. Adline de Cruyter; New York: 2000. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TL, Ward JV. African American adolescents and skin color. Journal of Black Psychology. 1995;21(3):256–274. [Google Scholar]

- Rondilla JL, Spickard P. Is lighter better?: Skin-tone discrimination among Asian Americans. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; Lanham: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, Porter M. “Everything's there except money”: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(3):680–696. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MS, Keith VM. The black the berry: Gender, skin tone, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Gender and Society. 2001;15(3):336–357. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Young-DeMarco L. Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United Sates: The 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1009–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Udry JR, Bauman KE, Chase C. Skin color, status, and mate selection. American Journal of Sociology. 1971;76(4):722–733. [Google Scholar]

- Uecker JE, Stokes CE. Early marriage in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(4):835–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller MR, McLanahan SS. “His” and “her” marriage expectations: Determinants and consequences. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(1):53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder J, Cain C. Teaching and learning color consciousness in black families: Exploring family processes and women's experiences with colorism. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32(5):577–604. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby BJ, Carroll JS. Sexual experience and couple formation attitudes among emerging adults. Journal of Adult Development. 2010;17:1–11. [Google Scholar]