Abstract

We examined the use of employment-based abstinence reinforcement in out-of-treatment injection drug users, in this secondary analysis of a previously reported trial. Participants (N = 33) could work in the therapeutic workplace, a model employment-based program for drug addiction, for 30 weeks and could earn approximately $10 per hr. During a 4-week induction, participants only had to work to earn pay. After induction, access to the workplace was contingent on enrollment in methadone treatment. After participants met the methadone contingency for 3 weeks, they had to provide opiate-negative urine samples to maintain maximum pay. After participants met those contingencies for 3 weeks, they had to provide opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples to maintain maximum pay. The percentage of drug-negative urine samples remained stable until the abstinence reinforcement contingency for each drug was applied. The percentage of opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples increased abruptly and significantly after the opiate- and cocaine-abstinence contingencies, respectively, were applied. These results demonstrate that the sequential administration of employment-based abstinence reinforcement can increase opiate and cocaine abstinence among out-of-treatment injection drug users.

Keywords: contingency management, abstinence reinforcement, cocaine addiction, opiate addiction, employment

Injection drug use is associated with several health-related problems. For example, injection drug users are at risk for contracting and spreading human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) through the sharing of injection equipment (Nelson et al., 2002; Sullivan, Metzger, Fudala, & Fiellin, 2005). Injection drug use accounts for a substantial proportion of the HIV infections in the United States and worldwide (Sullivan et al., 2005). Methadone maintenance, an opioid replacement therapy, is recognized as an effective means of reducing drug-related HIVrisk behaviors and HIV incidence and prevalence, because it reduces opioid use and, in turn, injection frequency (Barthwell, Senay, Marks, & White, 1989; Booth, Crowley, & Zhang, 1996; Farrell, Gowing, Marsden, Ling, & Ali, 2005; Friedman, Jose, Deren, Des Jarlais, & Neaigus, 1995; Metzger et al., 1993). Despite methadone’s effectiveness, most injection drug users remain outside the treatment system (Al-Tayyib & Koester, 2011; Kleber, 2008; Peterson et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2008; Zaller, Bazazi, Velazquez, & Rich, 2009). Interventions have been developed to engage out-of-treatment drug users, but about half or more of the individuals exposed to these interventions do not enter treatment, and many who do enroll in treatment continue to use opiates and cocaine during treatment (Booth, Corsi, & Mikulich, 2003; Booth, Kwiatkowski, Iguchi, Pinto, & John, 1998; Strathdee et al., 2006). Further development of interventions to engage out-of-treatment injection drug users in methadone treatment and promote abstinence is needed.

A potential method to promote engagement in methadone treatment and drug abstinence is the therapeutic workplace (Silverman, 2004; Silverman, DeFulio, & Sigurdsson, 2012). The therapeutic workplace intervention integrates therapeutic reinforcement contingencies into an employment program. In this program, unemployed, drug-dependent adults are hired and paid as employees in a model workplace. To access the workplace and maintain maximum pay, participants are required to provide drug-negative urine samples or adhere to medication treatment. The therapeutic workplace has been shown effective in initiating (Silverman et al., 2007, 2012; Silverman, Svikis, Robles, Stitzer, & Bigelow, 2001) and maintaining (DeFulio, Donlin, Wong, & Silverman, 2009; Silverman et al., 2002) cocaine abstinence in methadone patients and adherence to naltrexone in opioid-dependent adults (De-Fulio et al., 2012; Dunn et al., 2013; Everly et al., 2011). We recently examined whether employment-based reinforcement, delivered via the therapeutic workplace, could promote engagement in methadone treatment and drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users (Holtyn et al., 2014). After a 4-week induction, participants were randomly assigned to a condition in which they could work independent of their methadone treatment status and urinalysis results (work reinforcement condition), a condition in which they had to be enrolled in methadone treatment to work and maintain maximum pay (methadone and work reinforcement condition), or a condition in which they had to be enrolled in methadone treatment and had to provide opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples to work and maintain maximum pay (abstinence, methadone, and work reinforcement condition). The employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingencies had only modest effects on drug abstinence when the urine results were summed across the treatment phase; abstinence, methadone, and work reinforcement participants provided significantly more drug-negative urine samples than work reinforcement participants, but did not provide significantly more drug-negative urine samples than the methadone and work reinforcement participants.

Close review of the data showed that some of the abstinence, methadone, and work reinforcement participants were either not exposed or were exposed only briefly to the abstinence contingencies. This resulted from the fact that the abstinence reinforcement contingencies were administered sequentially for methadone adherence, opiate-negative urine samples, and cocaine-negative urine samples. Initially, participants had to enroll in methadone treatment to work and earn maximum pay. After they met the methadone contingency for 3 weeks, they also had to provide opiate-negative urine samples to maintain maximum pay. After meeting the opiate contingency for 3 weeks, participants also had to provide opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples to maintain maximum pay. However, the sequential administration may have obscured the effects of the abstinence contingencies because the drug abstinence results previously reported were based on the intent-to-treat sample, which included data from all participants, independent of whether or not they were exposed to the different contingencies.

The sequential administration was used to address the difficulty inherent in promoting abstinence from multiple drugs (Griffith, Rowan-Szal, Roark, & Simpson, 2000; Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006; Prendergast, Podus, Finney, Greenwell, & Roll, 2006). Approaches that require immediate cessation from all drugs can result in early treatment dropout (Higgins et al., 1991) and, for participants retained in treatment, limited to no contact with the reinforcement contingency due to a failure to provide polydrug negative urine samples (e.g., Downey, Helmus, & Schuster, 2000). Polydrug use can be resistant to contingency-management interventions (e.g, Downey et al., 2000; Iguchi, Belding, Morral, Lamb, & Husband, 1997) except under certain circumstances, such as when high-magnitude reinforcers are delivered (e.g., Dallery, Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 2001). Given that previous research suggests that a sequential approach may be effective at promoting abstinence from multiple drugs (e.g., Budney, Higgins, Delaney, Kent, & Bickel, 1991) and given the need for the development of approaches to address polydrug use, further examination of the efficacy of a sequential administration of abstinence contingencies in polydrug users is warranted.

The present secondary analysis was conducted to provide a more detailed assessment of the contribution of the abstinence reinforcement component of the intervention. This analysis examined the effects of the abstinence reinforcement contingencies using a multiple baseline design across drugs, and included only participants who were exposed to each contingency.

METHOD

Data for this study were collected during a clinical trial that investigated the efficacy of the therapeutic workplace in promoting enrollment in methadone treatment and drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users (see Holtyn et al., 2014). The analyses presented in this report are limited to participants who were randomized to an employment-based abstinence reinforcement condition, because only those participants could have been exposed to the abstinence reinforcement contingencies of interest.

Setting and Participant Selection

The clinical trial was conducted in the therapeutic workplace at the Center for Learning and Health, a treatment-research unit at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (Baltimore, MD). During the clinical trial, participants signed into the workplace at a urinalysis laboratory and provided observed urine samples when required. The laboratory was located in close proximity to three workrooms in which participants worked at individual stations equipped with a computer and a desk (see Silverman et al., 2007, for a detailed description of the therapeutic workplace setting and procedures). Of the 266 individuals screened for the clinical trial, 99 did not qualify, five did not complete the intake interview, and eight declined participation or dropped out. The remaining 154 participants were enrolled in the trial. Of these 154 participants, 56 did not complete induction. Of the remaining 98 participants, 33 were randomly assigned to the abstinence, methadone, and work reinforcement condition and were included in the present analyses.

Participants in the clinical trial were recruited between December 2008 and November 2011. During this time, waiting lists for methadone treatment in Baltimore were common; however, interim methadone treatment was available if a methadone maintenance treatment slot was not open. Participants were recruited through agencies that served the target population, street outreach, and a respondent-driven sampling referral system in which study participants were paid for successfully referring others to the study. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent. Study inclusion criteria required that participants were at least 18 years old, reported injection drug use in the past 30 days, met the criteria for opioid dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), reported using heroin at least 21 of the past 30 days, provided an opiate-positive urine sample, showed visible signs of injection drug use (i.e., track marks), reported not receiving substance abuse treatment in the past 30 days, lived in Baltimore City, and were unemployed. Participants were excluded if they had a current severe psychiatric disorder or a chronic medical condition that would interfere with their ability to participate in the workplace, reported current suicidal or homicidal ideation, had physical limitations that would prevent them from using a keyboard, had medical insurance coverage (this would disqualify them from receiving interim methadone treatment), were currently considered a prisoner, or were pregnant or breastfeeding (pregnant women were referred to local specialized services for pregnant, out-of-treatment drug users, and breastfeeding women and those in the early postpartum period were referred to community-based comprehensive services and were not enrolled in this clinical trial).

Eligible participants were invited to attend the workplace for a 4-week induction. The induction period was included to provide exposure to the workplace (and the relevant reinforcers) before the implementation of any contingencies. During induction, participants were invited to attend the workplace and were encouraged to enroll in methadone treatment. They were asked if they would like to schedule an intake appointment for methadone treatment at one of the study’s participating treatment programs. If a participant expressed interest in an appointment, he or she selected a preferred program, and study staff scheduled the appointment and provided the participant with an appointment card. Participants could attend the workplace for 4 hr every weekday and could earn an hourly wage of $8 (hereafter base pay) as well as about $2 per hour for their performance on training programs (hereafter productivity pay). They were paid in vouchers that were exchangeable for goods and services. Urine samples were collected on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and tested for opiates and cocaine.

Participants who completed the induction period (i.e., those who attended the workplace for at least 5 min on 2 of 5 workdays in the last week of induction) were invited to participate in the main randomized clinical trial, randomly assigned to one of three conditions, and invited to attend the workplace for an additional 26 weeks. Participants were randomly assigned to the work reinforcement condition, the methadone and work reinforcement condition, or the abstinence, methadone, and work reinforcement condition. Those assigned to the abstinence, methadone, and work reinforcement condition were included in the analyses reported here, and their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Intake (N = 33)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 44 (9) |

| Gender (%) | |

| Female | 45 |

| Male | 55 |

| Race (%) | |

| Black | 73 |

| White | 27 |

| Married (%) | 27 |

| High school diploma or GED (%) | 61 |

| HIV positive (%) | 6 |

| Living in poverty (%) | 97 |

| Felony conviction (%) | 85 |

| DSM IV diagnosis (%) | |

| Opioid dependent | 100 |

| Cocaine dependent | 55 |

| Days used, past 30 days, mean (SD) | |

| Heroin | 29 (2) |

| Cocaine | 10 (11) |

| Wide Range Achievement | |

| Test grade levels, mean (SD) | |

| Reading | 7 (3) |

| Spelling | 7 (4) |

| Arithmetic | 6 (3) |

Design

The analyses reported here were designed to evaluate whether the opiate and cocaine abstinence reinforcement contingencies applied to participants in the abstinence, methadone, and work reinforcement condition increased the percentage of urine samples negative for opiates and cocaine. The present study used a multiple baseline design across drugs. One week after randomization and after a participant had been enrolled in methadone treatment for 3 consecutive weeks, an opiate-abstinence contingency was implemented. After 3 consecutive weeks of meeting the opiate-abstinence requirement, the abstinence contingency was expanded to include cocaine. The analyses were designed to determine if opiate abstinence increased selectively when the opiate-abstinence reinforcement contingency was applied, and if cocaine abstinence increased selectively when the cocaine-abstinence reinforcement contingency was applied.

Methadone and Abstinence Reinforcement Procedure

Methadone contingency

One week after randomization, participants were exposed to an employment-based methadone reinforcement contingency in which they were required to be enrolled in methadone treatment to work and to maintain maximum pay. If a participant was not enrolled, he or she was not allowed to work the next day or any day thereafter until methadone treatment was initiated or resumed. In addition, the participant’s base pay was temporarily reset from $8 per hour to $1 per hour. After the reset, base pay could increase by $1 per hour to the maximum of $8 per hour for every day that the participant was enrolled in methadone treatment and attended the workplace for at least 5 min.

Opiate-abstinence contingency

After a participant had been enrolled in methadone treatment for 3 consecutive weeks, an opiate-abstinence contingency was implemented. Under this contingency, mandatory urine samples were collected on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Urinary morphine concentrations had to be less than 300 ng/ml or at least 20% lower than the last sample that was submitted (Preston, Silverman, Schuster, & Cone, 1997). Failure to provide a sample or to meet the abstinence requirement resulted in a base pay reset from $8 per hour to $1 per hour. After the reset, base pay increased by $1 per hour to the maximum of $8 per hour for every day that the participant provided an opiate-negative sample.

Cocaine-abstinence contingency

After 3 consecutive weeks of meeting the opiate-abstinence requirement, the abstinence contingency was expanded to cocaine. Participants had to provide urinalysis evidence of abstinence from both opiates and cocaine on mandatory urine days to maintain maximum pay (i.e., urinary morphine and benzoylecgonine concentrations had to be less than 300 ng/ml or at least 20% lower than the last sample submitted). If they failed to provide a sample or failed to meet these criteria, their base pay was reset as described above.

General Procedure

Every Monday, participants were asked if they were in methadone treatment. If they indicated that they were in treatment, their methadone program was contacted to confirm enrollment. Participants who were not enrolled were again asked if they would like to schedule an appointment for methadone treatment, were informed that they could not work and that they would receive a base pay reset, and received instructions on how they could work again and increase their base pay.

On mandatory urine days, participants were required to submit samples in a bathroom attached to the laboratory; samples were collected under observation by a same-sex staff member. The sample was tested for opiates and cocaine using an Abbott AxSYM system. If contingency requirements were met or if no requirements were in effect, participants were given their identification card (a personal card provided at the start of induction that was used to monitor time spent in the workplace). If abstinence requirements were not met, they were informed that they would receive a base pay reset and received instructions on how their base pay could increase again. Then, participants who met the methadone contingency were given their identification cards.

Workroom procedures

After receiving their identification cards, participants reported to a workroom staff member, who would then swipe the card through a barcode reader to sign a participant into the workroom. Participants worked on computer-based typing and keypad training programs and the Individual Prescription for Achieving State Standards (iPASS) math program (iLearn, 2013). The typing and keypad programs taught participants to type characters using a QWERTY keyboard and a numeric keypad and consisted of a series of steps that were practiced in 1-min timings. After a timing, the number of correct and incorrect characters as well as any productivity pay for typing the characters were displayed on the computer screen (for additional details on the programs, see Koffarnus et al., 2013). The iPASS program provided individualized math instruction based on the skill level of the participant; participants were assigned to a specific unit based on their placement-test performance. The units increased in difficulty as they progressed through the program. Participants could earn productivity pay for advancing in the program and answering questions correctly. They worked on the training programs for 2 hr in the morning (10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.) and for 2 hr in the afternoon (1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.).

Written instructions

Participants were given written instructions detailing the procedures of the therapeutic workplace before induction and whenever a new contingency was implemented. Instructions were read aloud by a staff member as a participant followed along on paper. To ensure understanding, participants were required to answer multiple-choice questions placed throughout the instructions. They could earn $0.20 for every correct answer and $0.10 for each corrected error.

Data Analysis

Both visual inspection and statistical analyses were used to evaluate the effects of the abstinence contingencies. For opiates and cocaine, dichotomous outcome measures (e.g., opiate-positive vs. opiate-negative urine samples) were aggregated across participants for the nine samples before and the nine samples following the onset of each contingency. This resulted in a precontingency percentage of negative samples and postcontingency percentage of negative samples. The percentage of samples that tested negative before and after the onset of each contingency were compared for both opiates and cocaine using Wilcoxon signed ranks tests. For all analyses, urine samples were considered negative for opiates and cocaine if morphine and benzoylecgonine concentrations, respectively, were less than 300 ng/ml. To address the problem of missing data, two analyses were conducted that differed in how the missing urine samples were treated. For the missing positive analyses, missing samples were considered positive for opiates and cocaine. For the missing missing analyses, missing samples were not replaced. Because both methods yielded similar results, only the missing positive analyses are presented here.

RESULTS

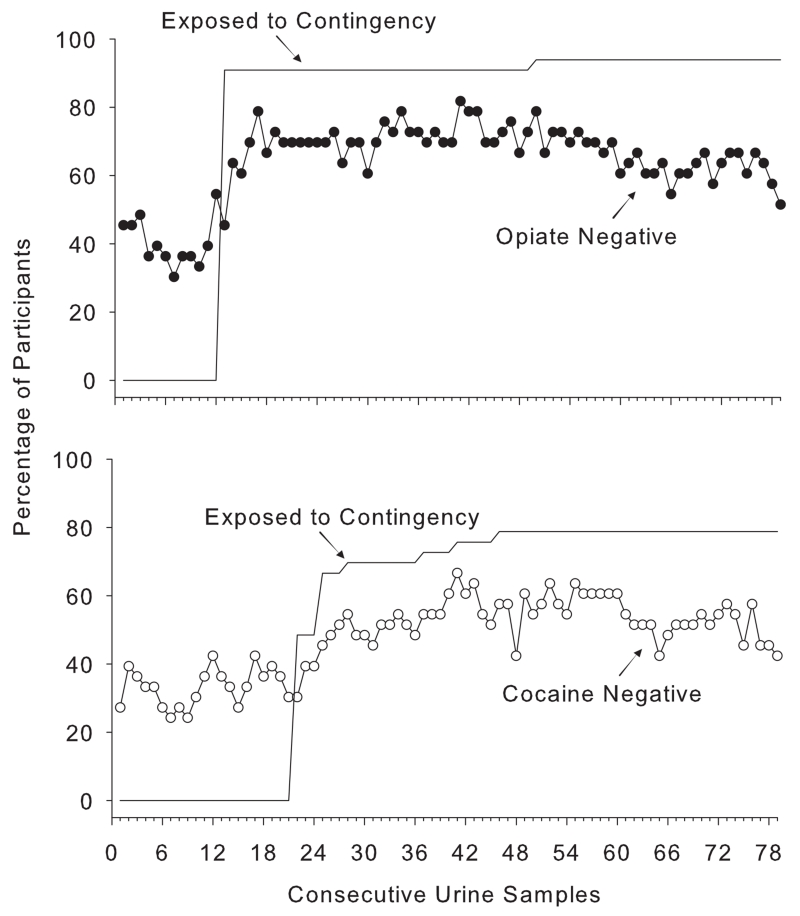

Figure 1 provides a summary of the urinalysis results across the entire 26-week intervention. The filled and open circles show the percentage of participants who provided opiate-negative (top) and cocaine-negative (bottom) urine samples and the solid horizontal line represents the percentage of participants cumulatively exposed to the opiate- (top) and cocaine-abstinence (bottom) reinforcement contingency. Because exposure to the opiate- and cocaine-abstinence reinforcement contingencies was dependent on participants’ enrollment in methadone treatment and opiate abstinence, respectively, participants were exposed to the contingencies at different times during the intervention. Shortly before the opiate-abstinence contingency was imposed for many participants (urine Samples 10 to 12), there was a slight increase in the percentage of opiate-negative urine samples. Nevertheless, the percentage of opiate-negative and cocaine-negative urine samples increased in proportion to the cumulative percentage of participants who were exposed to the opiate- and cocaine-abstinence contingencies, respectively.

Figure 1.

The percentage of participants with urine samples negative for opiates (top) and cocaine (bottom) submitted over the 26-week intervention. The horizontal line shows the percentage of participants cumulatively exposed to the opiate- (top) and cocaine-abstinence (bottom) contingencies. All missing values were coded as positive.

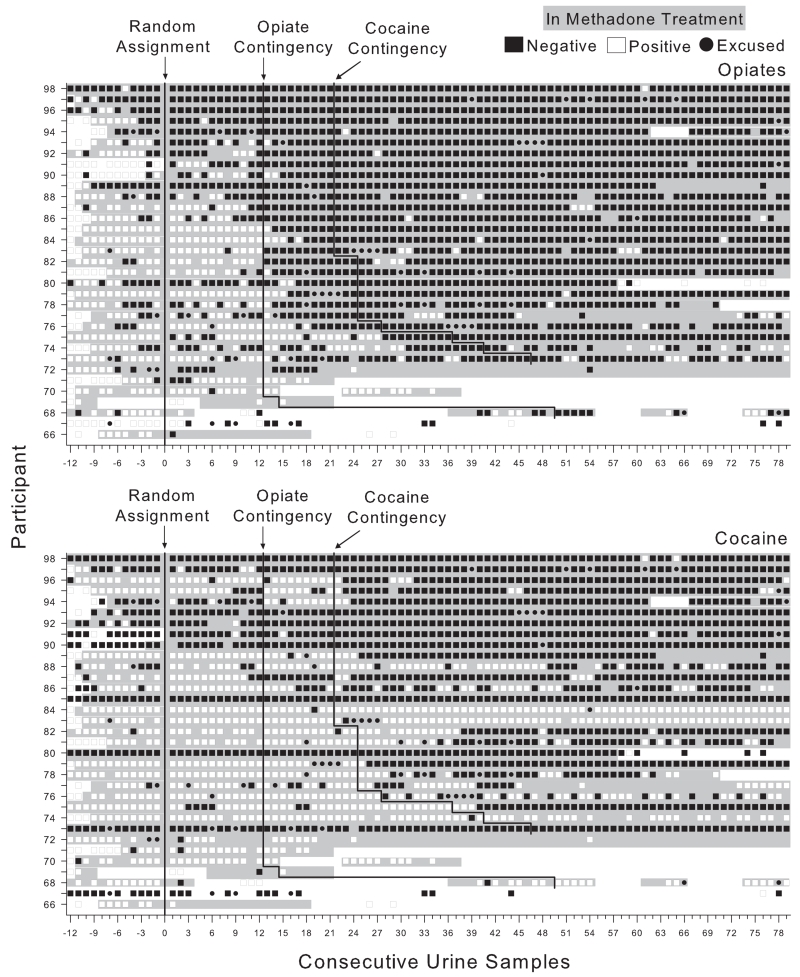

Figure 2 shows opiate (top) and cocaine (bottom) urinalysis results and also illustrates methadone enrollment for each participant. Most participants enrolled in methadone treatment during the induction period (before random assignment, and as indicated by the shading seen to the left of the first vertical line in the top panel) and remained in treatment throughout participation in the therapeutic workplace. Twenty-four of the 33 participants were enrolled in methadone treatment for the entire 26-week intervention period, eight participants were enrolled for only part of the intervention period (Participants 66, 68 to 71, 78, 80, and 94), and one participant never enrolled in treatment (Participant 67). During induction, most participants provided urine samples that were positive for opiates and cocaine (about 89% of urine samples). Some participants provided a greater percentage of opiate-negative urine samples after enrollment in methadone treatment than before enrollment. After the opiate-abstinence contingency was implemented, 15 participants submitted opiate-negative samples on the first day of the opiate contingency, whereas others did not initiate long periods of sustained opiate abstinence until several days or weeks after the onset of the contingency. Twenty-six of the 33 participants initiated or maintained periods of abstinence that lasted for 4 or more weeks.

Figure 2.

Opiate (top graph) and cocaine (bottom graph) urinalysis results across consecutive thrice weekly urine samples collected when participants attended the therapeutic workplace. The rows represent the results for individual participants. Samples to the left of the vertical line labeled “Random Assignment” were collected during induction. Filled squares indicate drug-negative urine samples, and open squares indicate drug-positive urine samples. Empty sections indicate missing samples. Shaded background for a row indicates that the participant was enrolled in methadone treatment. The filled circles indicate excused abstinences due to workplace closings and documented incarcerations.

Similar to the opiate-abstinence contingency, there was considerable variability in participants’ responses to the cocaine-abstinence contingency. Ten participants submitted cocaine-negative urine samples on the first day of the cocaine contingency, whereas others continued to submit positive samples. Eighteen of the 33 participants initiated or maintained periods of cocaine abstinence that lasted for 4 or more weeks. Although there was a decrease in the percentage of opiate-negative urine samples across the final samples (see Figure 1), Figure 2 shows that many participants were able to achieve and sustain opiate and cocaine abstinence.

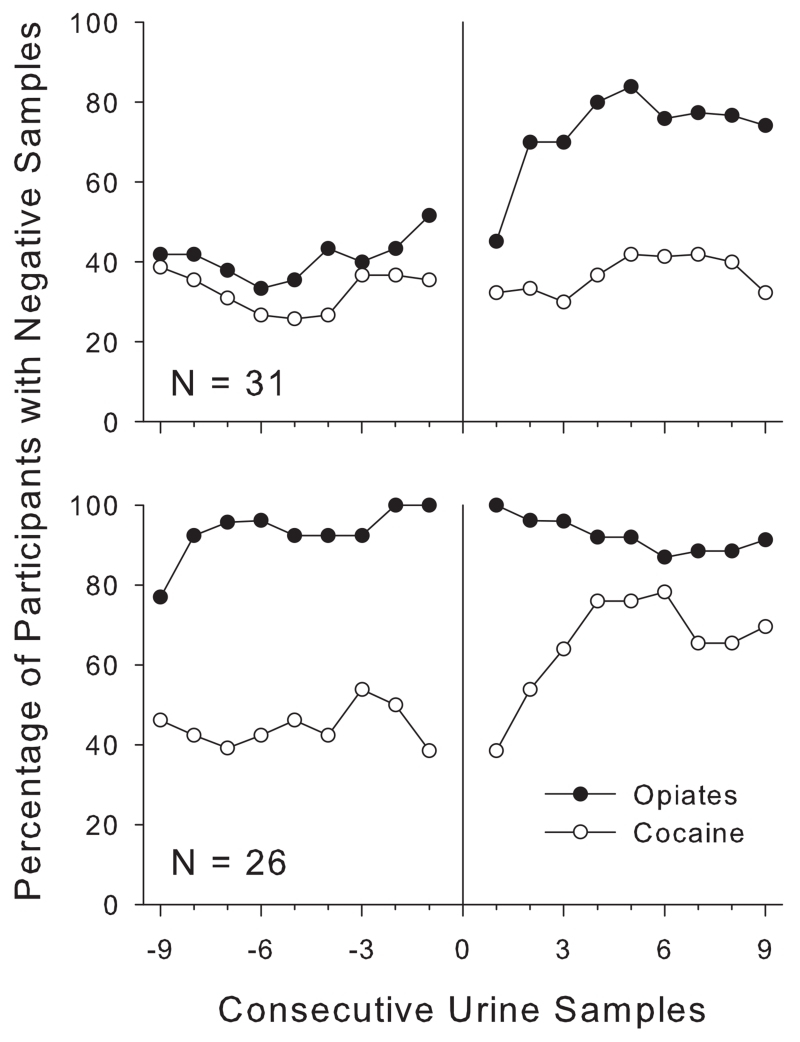

Figure 3 shows the selective effects of the abstinence reinforcement contingencies by including only those participants who were exposed to the contingencies and by showing the percentage of urine samples negative for opiates and cocaine immediately before and after the onset of the opiate- and cocaine-abstinence contingencies, respectively. Results for the 31 participants who were exposed to the opiate-abstinence reinforcement contingency are shown in the top panel, and results for the 26 participants who were exposed to the cocaine-abstinence reinforcement contingency are shown in the bottom panel. The percentages of participants abstinent from opiates and cocaine for the nine samples before and the nine samples following onset of the opiate- (top) and cocaine-abstinence (bottom) contingency are shown. The percentage of participants who provided opiate-negative urine samples (filled circles, top) was relatively stable before introduction of the opiate-abstinence contingency, although there was a slight upward trend across the last three urine samples. The percentage of participants who provided opiate-negative urine samples increased abruptly after the opiate-abstinence contingency was introduced, and remained at a level well above that shown before onset of the contingency. Participants provided significantly more opiate-negative urine samples after the onset of the opiate contingency than before (73% vs. 41%, respectively; p <.01). By comparison, the percentage of participants who provided cocaine-negative urine samples (open circles) remained at the same level before and after the opiate-abstinence reinforcement contingency was introduced (33% vs. 37%, respectively; p =.25).

Figure 3.

The percentage of urine samples negative for opiates (filled circles) and cocaine (open circles) relative to the onset of the opiate (top) and cocaine (bottom) contingency. Urinalysis results for the nine samples before and the nine samples following the onset of the contingency (represented at 0 on the x axis) are shown. All missing values were coded as positive.

When the cocaine-abstinence contingency was implemented (bottom), the percentage of cocaine-negative urine samples (open circles) increased abruptly and remained at a level well above that shown before onset of the contingency. Participants provided significantly more cocaine-negative urine samples after the onset of the cocaine contingency than before (65% vs. 45%, respectively; p <.01). However, the percentage of opiate-negative urine samples (filled circles) remained at the same level before and after the cocaine-abstinence reinforcement contingency was introduced (93% vs. 92%, respectively; p =.43).

DISCUSSION

The present secondary analysis provides evidence that employment-based abstinence reinforcement can increase opiate and cocaine abstinence among unemployed and out-of-treatment injection drug users. Participants were offered employment in a model workplace and were required to provide urinalysis evidence of recent drug abstinence to maintain maximum pay. By focusing on only those participants who were exposed to the opiate- and cocaine-abstinence contingencies, the present analyses show a statistically significant and clear difference in the percentage of participants who were able to initiate and maintain periods of sustained opiate and cocaine abstinence after exposure to each contingency. In addition, the present analyses provide information regarding the sequential administration of contingencies in promoting abstinence from opiates and cocaine, and suggest that the sequential administration of contingencies can be effective at promoting abstinence from multiple drugs. These effects were not evident in the intent-to-treat analysis reported previously (Holtyn et al., 2014).

Although the sequential administration of contingencies may be useful when polydrug use is targeted, the ability to detect effects of the abstinence contingencies using an intent-to-treat analysis may be limited by this design feature. In the primary clinical trial, exposure to the opiate- and cocaine-abstinence contingencies was dependent on participants’ enrollment in methadone treatment and opiate abstinence, respectively. As a result, some participants were never exposed to the contingencies, and others were exposed for only a portion of the 26-week intervention period. Theoretical and empirical models of operant behavior on which voucher-based abstinence reinforcement interventions are based have shown that reinforcer magnitude interacts with the response requirement. Specifically, if the response required to obtain a particular reinforcer is too effortful, the response is less likely to occur (Chung, 1965; Dallery et al., 2001; Miller, 1968). Thus, sequential administration was designed to lower the response requirement involved in abstaining from multiple drugs by first imposing the contingency on just one drug and then, after a period of abstinence, expanding the contingency to another drug (Dallery et al., 2001; Downey et al., 2000). However, in the primary clinical trial, the sequential administration obscured the effects of the contingencies, because the intent-to-treat analysis necessarily included urinalysis results from all participants across the entire 26-week intervention period. Future clinical trials that employ the sequential administration of abstinence contingencies may benefit from a fixed evaluation period during which all of the contingencies have been implemented and the subsequent analyses are conducted. Similar to procedures in which participants are inducted and stabilized on a specific drug dose before full evaluation at the targeted maintenance dose, the sequential administration of the abstinence contingencies may be considered to be part of an induction period, and full evaluation of the contingencies may be conducted after all of the contingencies have been implemented. Nevertheless, the present study highlights the utility of the multiple baseline design for detecting the additive effects of the abstinence contingencies.

Silverman et al. (2007) reported that imposing abstinence contingencies in a group of injection drug users who were enrolled in methadone treatment reduced attendance in the workplace. This effect was not seen in the present study. During the intervention period of this study, participants attended the workplace on approximately 71% of days compared to 39% reported by Silverman et al. In addition, rates of attendance in the present study were similar before and after implementation of the abstinence contingencies. It is possible that the different consequences of providing drug-positive urine samples across the two studies contributed to this difference. In Silverman et al., participants who did not meet an abstinence requirement could not work until they provided a drug-negative urine sample and received a temporary base-pay reset. In comparison, participants in the present study received only a base-pay reset. The opportunity to engage in paid work, albeit at a reduced hourly wage, after failure to meet an abstinence requirement may have promoted more consistent attendance.

Although drug use was the targeted behavior in the present study, most participants displayed other characteristics that could impede long-term therapeutic behavior change. Participants had histories of chronic unemployment, poverty, and criminal behavior in addition to their persistent illicit drug use; 100% of participants were unemployed, 97% were living in poverty, and 85% had a felony conviction (see Table 1). Although 61% of participants had a high school diploma or GED, most of them had reading, spelling, and math skills that were at or below the seventh-grade level. It is not uncommon for participants of the therapeutic workplace to exhibit deficits in basic educational skills (Holtyn, DeFulio, & Silverman, in press) and professional demeanor (Carpenedo et al., 2007; Sigurdsson, Ring, O’Reilly, & Silverman, 2012; Wong & Silverman, 2007). Because many clinicians believe employment plays a vital role in recovery (Magura, 2003), a major aim of the therapeutic workplace is the development of skills that will allow participants to overcome some of the barriers to employment noted above and gain employment after participation in the workplace ends. Future research may benefit from the examination of the degree to which the therapeutic workplace procedures and outcomes produce socially meaningful improvements in job skills, employment, and economic status for participants.

The present study shows that employment-based abstinence reinforcement can be effective in promoting abstinence from opiates and cocaine even in out-of-treatment injection drug users who are at considerable risk for persistent drug use and HIV. Application of employment-based abstinence reinforcement for drug-addicted populations could be useful as a long-term treatment to address the interrelated and intractable problems of drug addiction, unemployment, HIV, and poverty.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants R01DA023864, K24DA023186, and T32DA07209 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We thank Jeanne Harrison for her assistance with data management and study coordination, Jackie Hampton for participant recruitment and assessment, and David Pierce and Josh DiGiacomo for their help with data analyses.

Contributor Information

August F. Holtyn, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Mikhail N. Koffarnus, VIRGINIA TECH CARILION RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Anthony DeFulio, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE.

Sigurdur O. Sigurdsson, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE, AND FLORIDA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

Eric C. Strain, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Robert P. Schwartz, FRIENDS RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Kenneth Silverman, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE.

REFERENCES

- Al-Tayyib AA, Koester S. Injection drug users’ experience with and attitudes toward methadone clinics in Denver, CO. Journal of Substance Abuse Treament. 2011;41:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.009. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Barthwell A, Senay E, Marks R, White R. Patients successfully maintained with methadone escaped human immunodeficiency virus infection. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:957–958. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810100099020. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810100099020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Corsi KF, Mikulich SK. Improving entry to methadone maintenance among out-of-treatment injection drug users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treament. 2003;24:305–311. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00038-2. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Crowley TJ, Zhang Y. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention and effectiveness: Out-of-treatment opiate injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;42:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01257-4. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Kwiatkowski C, Iguchi MY, Pinto F, John D. Facilitating treatment entry among out-of-treatment injection drug users. Public Health Reports. 1998;113:116–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Kent L, Bickel WK. Contingent reinforcement of abstinence with individuals abusing cocaine and marijuana. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:657–665. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-657. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenedo CM, Needham M, Knealing TW, Kolodner K, Fingerhood M, Wong CJ, Silverman K. Professional demeanor of chronically unemployed cocaine-dependent methadone patients in a therapeutic workplace. Substance Use and Misuse. 2007;42:1141–1159. doi: 10.1080/10826080701410089. doi: 10.1080/10826080701410089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. Effects of effort on response rate. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1965;8:1–7. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1965.8-1. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1965.8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of opiate plus cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcer magnitude. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:317–325. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.317. doi: 10.1007/s002130051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFulio A, Donlin WD, Wong CJ, Silverman K. Employment-based abstinence reinforcement as a maintenance intervention for the treatment of cocaine dependence: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104:1530–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02657.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFulio A, Everly JJ, Leoutsakos JS, Umbricht A, Fingerhood M, Bigelow GE, Silverman K. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to an FDA approved extended release formulation of naltrexone in opioid-dependent adults: A randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;120:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.023. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey KK, Helmus TC, Schuster CR. Treatment of heroin-dependent poly-drug abusers with contingency management and buprenorphine maintenance. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:176–184. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.176. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.8.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KE, Defulio A, Everly JJ, Donlin WD, Aklin WM, Nuzzo PA, Silverman K. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to oral naltrexone treatment in unemployed injection drug users. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21:74–83. doi: 10.1037/a0030743. doi: 10.1037/a0030743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everly JJ, DeFulio A, Koffarnus MN, Leoutsakos JS, Donlin WD, Aklin WM, Silverman K. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to depot naltrexone in unemployed opioid-dependent adults: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2011;106:1309–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03400.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Gowing L, Marsden J, Ling W, Ali R. Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment in HIV prevention. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16:S67–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.02.008. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Jose B, Deren S, Des Jarlais DC, Neaigus A. Risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among out-of-treatment drug injectors in high and low seroprevalence cities: The national AIDS research consortium. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142:864–874. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, Simpson DD. Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: A meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00068-x. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, Fenwick JW. A behavioral approach to achieving initial cocaine abstinence. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1218–1224. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1218. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtyn AF, DeFulio A, Silverman K. Academic skills of chronically unemployed drug-addicted adults. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. doi: 10.3233/JVR-140724. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtyn AF, Koffarnus MN, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO, Strain EC, Schwartz RP, Silverman K. The therapeutic workplace to promote treatment engagement and drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.021. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi MY, Belding MA, Morral AR, Lamb RJ, Husband SD. Reinforcing operants other than abstinence in drug abuse treatment: An effective alternative for reducing drug use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:421–428. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.421. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.65.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iLearn 2013 Retrieved from http://www.ilearn.com/web/ipass.html.

- Kleber HD. Methadone maintenance 4 decades later: Thousands of lives saved but still controversial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:2303–2305. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.648. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Wong CJ, Fingerhood M, Svikis DS, Bigelow GE, Silverman K. Monetary incentives to reinforce engagement and achievement in a job-skills training program for homeless, unemployed adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:582–591. doi: 10.1002/jaba.60. doi: 10.1002/jaba.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S. The role of work in substance dependency treatment: A preliminary overview. Substance Use and Misuse. 2003;38:1865–1876. doi: 10.1081/ja-120024244. doi: 10.1081/JA-120024244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP, Druley P, Navaline H, Abrutyn E. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: An 18-month prospective follow-up. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1993;6:1049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LK. Escape from an effortful situation. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1968;11:619–627. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-619. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KE, Galai N, Safaeian M, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD, Vlahov D. Temporal trends in the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus infection and risk behavior among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland, 1988-1998. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;156:641–653. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf086. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JA, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Reisinger HS, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Agar MH. Why don’t out-of-treatment individuals enter methadone treatment programs? International Journal of Drug Policy. 2010;21:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.07.004. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Silverman K, Schuster CR, Cone EJ. Assessment of cocaine use with quantitative urinalysis and estimation of new uses. Addiction. 1997;92:717–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb02938.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Mitchell SG, Peterson JA, Reisinger HS, Brown BS. Attitudes toward buprenorphine and methadone among opioid-dependent individuals. The American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17:396–401. doi: 10.1080/10550490802268835. doi: 10.1080/10550490802268835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson SO, Ring BM, O’Reilly K, Silverman K. Barriers to employment among unemployed drug users: Age predicts severity. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:580–587. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643976. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K. Exploring the limits and utility of operant conditioning in the treatment of drug addiction. The Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:209–230. doi: 10.1007/BF03393181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO. Maintenance of reinforcement to address the chronic nature of drug addiction. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55:S46–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.013. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Svikis D, Robles E, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: Six-month abstinence outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:14–23. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.9.1.14. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.9.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Svikis D, Wong CJ, Hampton J, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: Three-year abstinence outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;10:228–240. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.228. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.10.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Wong CJ, Needham M, Diemer KN, Knealing T, Crone-Todd D, Kolodner K. A randomized trial of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in injection drug users. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:387–410. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-387. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Ricketts EP, Huettner S, Cornelius L, Bishai D, Havens JR, Latkin CA. Facilitating entry into drug treatment among injection drug users referred from a needle exchange program: Results from a community-based behavioral intervention trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.015. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Metzger DS, Fudala PJ, Fiellin DA. Decreasing international HIV transmission: The role of expanding access to opioid agonist therapies for injection drug users. Addiction. 2005;100:150–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CJ, Silverman K. Establishing and maintaining job skills and professional behaviors in chronically unemployed drug abusers. Substance Use and Misuse. 2007;42:1127–1140. doi: 10.1080/10826080701407952. doi: 10.1080/10826080701407952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaller ND, Bazazi AR, Velazquez L, Rich JD. Attitudes toward methadone among out-of-treatment minority injection drug users: Implications for health disparities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009;6:787–797. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6020787. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6020787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]