Abstract

Purpose of review

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a severe form of vasculitis in the elderly. The recent discovery of varicella zoster virus (VZV) in the temporal arteries (TA) and adjacent skeletal muscle of patients with GCA, and the rationale and strategy for antiviral and corticosteroid treatment for GCA are reviewed.

Recent findings

The clinical features of GCA include excruciating headache/head pain, often with scalp tenderness, a nodular TA and decreased TA pulsations. Jaw claudication, night sweats, fever, malaise and a history of polymyalgia rheumatica (aching and stiffness of large muscles primarily in the shoulder girdle, upper back and pelvis without objective signs of weakness) are common. ESR and CRP are usually elevated. Diagnosis is confirmed by TA biopsy which reveals vessel wall damage and inflammation, with multinucleated giant cells and/or epithelioid macrophages. Skip lesions are common. Importantly, TA biopsies are pathologically negative in many clinically suspect cases. This review highlights recent virological findings in TAs from patients with pathologically-verified GCA and in TAs from patients who manifest clinical and laboratory features of GCA, but whose TA biopsies (Bx) are pathologically negative for GCA (Bx-negative GCA). Virological analysis revealed that VZV is present in most GCA-positive and GCA-negative TA biopsies, mostly in skip areas that correlate with adjacent GCA pathology.

Summary

The presence of VZV in Bx-positive and Bx-negative GCA TAs indicates that VZV triggers the immunopathology of GCA. However, the presence of VZV in about 20% of TA biopsies from non-GCA post-mortem controls also suggests that VZV alone is not sufficient to produce disease. Treatment trials should be performed to determine if antiviral agents confer additional benefits to corticosteroids in both Bx-positive and Bx-negative GCA patients. These studies should also examine whether oral antiviral agents and corticosteroids are as effective as intravenous acyclovir and corticosteroids. Appropriate dosage and duration of treatment also remain to be determined.

Keywords: varicella zoster virus (VZV), giant cell arteritis (GCA), temporal arteries (TA)

INTRODUCTION

VZV is an exclusively human neurotropic alphaherpesvirus. Primary VZV infection causes varicella (chickenpox), after which virus becomes latent in ganglionic neurons along the entire neuraxis. Decades later, when VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity declines with age, virus reactivates, usually leading to zoster (dermatomal-distribution pain and rash). Often, zoster pain lasts for months or years (postherpetic neuralgia). Unfortunately, zoster can be further complicated by other serious neurological diseases such as meningoencephalitis, cerebellitis, isolated or multiple cranial nerve palsies (polyneuritis cranialis), myelitis and vasculopathy, as well as multiple ocular disorders. Sequelae include paralysis, blindness and death. Importantly, as is characteristic of GCA, all of the neurological and ocular disorders listed above may also develop in the absence of rash. The incidence and severity of zoster is best viewed as a continuum in immunodeficient individuals, ranging from a natural decline in VZV-specific immunity with advancing age to more serious host immune deficits as encountered in organ transplant recipients and patients with cancer or AIDS.

VZV is the only human virus that has been shown to replicate in arteries and cause disease. In intracerebral arteries, productive VZV infection leads to VZV vasculopathy [1,2]. An exciting finding in the past few years is that productive VZV infection and vascular disease is not limited to the intracranial circulation; indeed, VZV infects extracranial TAs and leads to GCA. The search for VZV in GCA was motivated by virtually identical pathological changes seen in the arteries of patients with both intracerebral VZV vasculopathy and GCA. In both conditions, the pathology is characterized by granulomatous arteritis, in which inflammation, often transmural, is seen with necrosis, usually in the arterial media, accompanied by multinucleated giant cells, epithelioid macrophages or both. The fact that granulomatous arteritis characterizes both intracerebral VZV vasculopathy and GCA, combined with the presence of VZV in cerebral arteries of VZV vasculopathy, prompted examination of TA biopsies for VZV from patients with pathologically-verified GCA as well as from patients with clinical features and laboratory abnormalities of GCA whose TA biopsies were pathologically-negative for VZV.

CASE STUDIES

Historically, the role of VZV in GCA was suggested upon virological analysis of a TA biopsy from an 80-year-old man who developed left ophthalmic-distribution zoster and ipsilateral ischemic optic neuropathy (ION) [3]. The TA exhibited inflammation, but not GCA. VZV antigen was found primarily in the arterial adventitia and less so in the media of the TA. The patient did not improve after treatment with steroids. After VZV was found in the TA, the patient was immediately treated with intravenous acyclovir and his vision recovered. The patient was diagnosed with VZV-induced ION and subclinical TA infection. Importantly, the location of VZV mostly in the arterial adventitia suggested that after reactivation from ganglia, virus spread transaxonally to the adventitia followed by transmural spread to the media.

The second patient was a 75-year-old woman who developed periorbital pain and blurred vision OS. There was no history of zoster rash. Visual acuity was 20/40 OD, 20/400 OS, with a mild left relative afferent pupillary defect [4]. The left optic nerve was swollen and hyperemic with peripapillary flame hemorrhages. ESR was 124 mm/hr. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone, 250 mg q6h. On day 3, headache and vision improved. Rheumatoid factor, ANA and ANCA titers were negative. On day 4, left TA biopsy was GCA-negative and she began taking oral prednisone, 60 mg daily. Over the next week, pain and vision worsened, visual acuity was 20/400 OS with a relative left APD, and the left eye became blind and non-reactive to light; brain MRI with gadolinium and orbital CT and head CT angiography were negative. CSF contained 8 WBCs/mm3, protein 72 mg%, glucose 54 mg%; CSF cultures for bacteria, fungi, AFB and cytology were negative. Despite the absence of GCA pathology in the TA, a VZV ION was diagnosed and she was treated with intravenous acyclovir, 10 mg/kg q8h for 7 days. On day 31, the CSF contained anti-VZV IgG but not anti-HSV IgG antibody, and the serum-to-CSF ratio of anti-VZV IgG was markedly reduced (14) compared to normal ratios for total IgG (121) and albumin (81). Immunohistochemistry and pathology revealed VZV antigen and neutrophils in the original left TA specimen. She was treated with oral valacyclovir, 1 g TID for 6 weeks; prednisone was reduced to 20 mg daily and tapered to 5 mg/week. Six weeks later, pain resolved and visual acuity improved to finger-counting. The left optic nerve was pale, with clear margins and resolution of hemorrhage. Essentially, another case of VZV ION with sublinical TA infection was uncovered, this time with no history of zoster rash.

The next link of VZV vasculopathy with features of GCA was provided by a 54-year-old diabetic woman who developed unilateral ION followed by acute retinal necrosis with multiple areas of focal venous beading [5]. The vitreous fluid contained amplifiable VZV DNA, but not HSV-1, CMV or toxoplasma DNA. The clinical presentation was remarkable for jaw claudication and intermittent scalp pain, prompting a TA biopsy that was pathologically-negative for GCA but notable for the presence of VZV antigen. The case added to the clinical spectrum of multifocal VZV vasculopathy.

DETECTION OF VZV IN GCA-NEGATIVE TEMPORAL ARTERIES

Further efforts to address the incidence of VZV infection in archived GCA biopsy-negative TAs from subjects with clinically suspected GCA revealed VZV, but not HSV-1 antigen, in 5/24 (21%) TAs [6]. Thirteen normal TAs contained neither VZV nor HSV-1 antigen. Interestingly, all 5 subjects whose TAs contained VZV antigen presented with clinical and laboratory features of GCA that included early visual disturbances. It then became clear that multifocal VZV vasculopathy can present with the full spectrum of clinical features and laboratory abnormalities characteristic of GCA, and that in GCA-negative/VZV-positive TAs, viral antigen predominated in the arterial adventitia.

During the continuing search for VZV antigen in patients with GCA in whom TA Bxs were negative, the TA of one subject revealed abundant VZV antigen and VZV DNA in multiple regions (skip areas) spanning 350 μm, as well as in skeletal muscle adjacent to the infected TA; pathological analysis of sections adjacent to those containing viral antigen revealed inflammation involving the arterial media and abundant multinucleated giant cells characteristic of GCA [7]. In three other such cases, the detection of VZV in “TA Bx-negative GCA patients” led to additional pathological studies and a change in diagnosis to GCA.

RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS OF ARCHIVED GCA-POSITIVE AND -NEGATIVE TAs FOR VZV

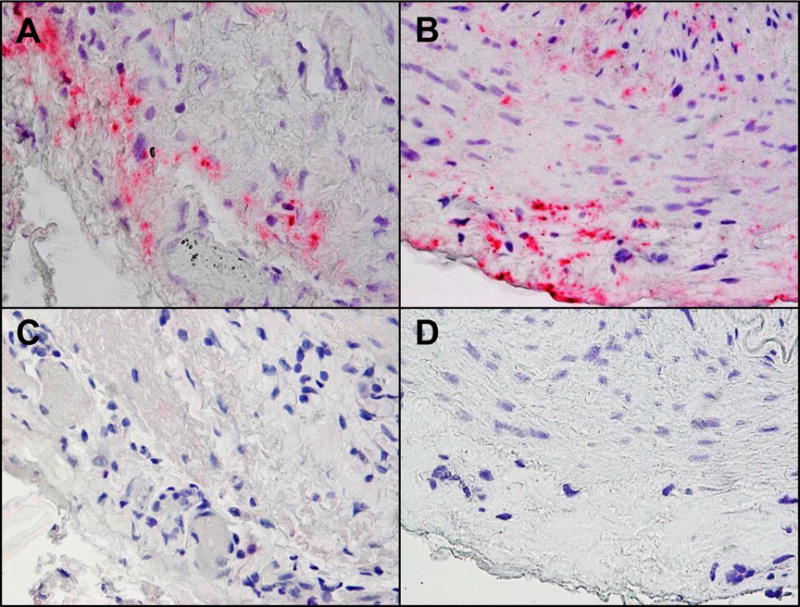

To test the hypothesis that VZV infection triggers the inflammatory cascade characteristic of GCA, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded GCA-positive TA biopsies (50 sections/TA), including adjacent skeletal muscle, and normal TA biopsies from subjects >50 years of age were examined for the presence and distribution of VZV antigen by immunohistochemistry and ultrastructurally for virions; adjacent regions were examined by hematoxylin-eosin staining. VZV antigen-positive slides were also analyzed by PCR for VZV DNA. Initially, VZV antigen was detected in 61/82 (74%) GCA-positive TAs compared with 1/13 (8%) normal TAs (p<0.0001). Most GCA-positive TAs contained viral antigen (Fig. 1A) in skip areas [8**]. VZV antigen, present mostly in the arterial adventitia followed by the media and intima, was also detected skeletal muscles adjacent to VZV antigen-positive TAs. Despite formalin fixation, VZV DNA was readily detected in 18/45 (40%) GCA-positive VZV antigen-positive TAs; 6/10 (60%) VZV antigen-positive skeletal muscles; and 1 VZV antigen-positive normal TA. VZ virions were also found in a GCA-positive TA. GCA pathology in sections adjacent to those containing VZV was seen in 89% of GCA-positive TAs, but not in any of 18 adjacent sections from normal TA. Overall, most GCA-positive TAs contained VZV in skip areas that correlated with adjacent GCA pathology. Moreover, transmission and scanning EM revealed herpesvirus particles in the same area that immunostained with anti-VZV antibody, and despite fixation, VZV DNA was readily amplifiable in many slides that contained VZV antigen. Together, the findings of VZV antigen, VZV DNA and VZ virions in TAs indicate productive virus infection.

FIGURE 1.

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) antigen in giant cell arteritis (GCA)-positive and GCA-Bx-negative temporal arteries (TAs). Immunohistochemical analysis with mouse anti-VZV gE IgG1 antibody shows VZV antigen in the adventitia of a GCA-positive TA (A) and in the adventitia, media and intima of a GCA-Bx-negative TA (B). No staining was seen when mouse anti-IgG1 isotype control antibody was substituted for the primary antibody (C & D). Magnification 600×.

The search for VZV was extended to patients with clinically-suspect GCA with histopathologically-negative TA biopsies [9**]. VZV antigen was found in 45/70 (64%) GCA-negative TAs (Fig. 1B) compared with 11/49 (22%) normal TAs (p<.001), and extension of our earlier study revealed VZV antigen in 68/93 (73%) of GCA-positive TAs compared with 11/49 (22%) normal TAs (p<.001). Compared to normal TAs, VZV antigen was more likely to be present in both GCA-Bx-negative TAs (p<.001) and GCA-positive TAs (p<.001).

Continuing immunohistochemical analyses have to date revealed VZV antigen in 73/104 (70%) GCA-positive and 58/100 (58%) GCA-Bx-negative TAs compared to 11/61 (18%) normal TAs [10]. Overall, VZV antigen was 3.89-fold more likely to be present in GCA-positive TAs than in normal TAs (95% CI = 2.3819, 7.2384, p<0.0001) and 3.22 times more likely to be present in GCA-Bx-negative TAs than in normal TAs (95% CI = 1.9391, 6.0303, p<0.0001). All TAs contained viral antigen in multiple arterial layers. In GCA-positive and GCA-Bx-negative subjects, viral antigen was seen in the adventitia (86% and 95%, respectively), media (67% and 53%, respectively) and intima (52% and 45%, respectively); in normal TAs, viral antigen was seen in the adventitia (91%) and equally in media (82%) and intima (82%).

Examination of 58 GCA-positive, VZV antigen-positive TAs for VZV DNA showed that all contained cellular DNA and 23 (40%) contained the viral DNA. Of 58 patients with GCA who were Bx-negative, VZV antigen-positive TAs were examined. Fifty-one contained cellular DNA, of which 9 (18%) contained VZV DNA. Nine of 11 normal VZV antigen-positive TAs contained cellular DNA, of which 3 (33%) contained VZV DNA. Adventitial inflammation was seen adjacent to viral antigen in 26 (52%) of 58 GCA-Bx-negative subjects whose TAs contained VZV antigen. No inflammation was seen in normal control TAs containing VZV antigen.

Overall, the detection of VZV mostly in the adventitia of GCA-positive TAs, together with the presence of VZV in the inflamed adventitia of GCA-Bx-negative TAs, indicates that inflammation follows VZV reactivation from ganglia and transaxonal transport to arterial adventitia. The more detailed steps in the evolution of GCA (transmural inflammation and necrosis with giant and/or epithelioid cells) after virus infection of the adventitia and adventitial inflammation remain to be determined.

Another important finding in our studies is that the presence of VZV DNA and VZV antigen in 18% of control TAs without inflammation indicates that VZV reactivates sub-clinically in some people over age 50. VZV DNA is found in latently infected human ganglia, but VZV expression is limited to the immediate-early VZV gene 63 RNA [11]. If VZV were latent in TAs, only VZV DNA would be found, not VZV late glycoproteins and VZ virions.

Together, our data suggest that the prevalence of VZV in the TAs of patients with clinically-suspected GCA is similar, independent of whether biopsy is negative or positive pathologically. Detection of adventitial inflammation adjacent to VZV antigen in 52% of GCA-Bx-negative TAs for the first time connects the presence of VZV with pathology in GCA-Bx-negative TAs. Inflammation restricted to the adventitia may represent a milder form of GCA [12] and has also been associated with ischemic optic neuropathy (ION) [6,13]. As noted above, we initially detected VZV in the TAs of patients with ION whose biopsy revealed both adventitial and intimal inflammation but not classical GCA [3].

In addition, we found that GCA-negative TA biopsies contained VZV antigen in 5/7 (71%) patients with anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION). Two VZV-positive, biopsy-negative AION cases had clinical features consistent with GCA. In one patient, GCA pathology was subsequently found adjacent to VZV antigen. Importantly, most patients with VZV-positive biopsies had atypical AION features (vascular gliosis at optic disc, sub-retinal hemorrhage and progressive vision loss), suggesting that VZV vasculopathy in AION produces a wider range of ischemia than in classical GCA. Due to the multifocal nature of VZV vasculopathy and the rich innervation of the vascular supply to optic nerve and retina, VZV vasculopathy may produce a spectrum of ischemic injuries such as anterior and posterior ION, retinal necrosis and central retinal artery occlusion [4–6]. Thus, a search for VZV in atypical AION cases with elevated cup/disc ratios, pain, retinal pathology or slow progression may identify individuals who could benefit from antiviral treatment. Additional prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate effects of antiviral therapy in these patients. Virological examination of TA biopsies in AION patients with or without clinical and laboratory findings for GCA may reveal VZV infection and should be included in the standard evaluation of AION patients. Extensive serial sections of TA biopsies should be examined for both GCA pathology and for VZV antigen, since patients whose TAs contain VZV may benefit from antiviral treatment.

NUMBER OF TA SECTIONS EXAMINED FOR VZV IS CRITICAL

Success in detecting VZV in TAs was largely based on immunostaining of no less than 50 sections of every TA in all studies above; immunohistochemistry using VZV-specific antibodies did not detect VZV antigen when only one section from each TA was analyzed [14]. PCR in earlier studies to examine fixed GCA-positive and -negative TAs for VZV did not reveal VZV DNA when 1–6 sections per TA were examined [14–17], whereas analysis of 4–6 sections detected VZV DNA in 9/35 (26%) GCA-positive TAs [18], and examination of 10 sections detected VZV DNA in 18/57 (32%) specimens from GCA-positive TAs and in 18/56 (32%) of GCA-negative TAs [19]. Meanwhile, examination of 25 sections of each formalin-fixed TA biopsy specimen revealed VZV antigen in 5/24 (21%) GCA-negative TAs [20]. Overall, our detection of VZV antigen in most GCA-positive and GCA-Bx-negative TAs indicates the value of staining many sections, most likely increasing detection of virus in skip regions. Immunostaining of several hundred sections of each GCA-positive TA might reveal VZV in nearly all GCA-positive arteries.

DISTRIBUTION OF VZV IN THE TA AND PRESENCE OF VZV IN SKIP AREAS INFORM PATHOGENESIS

The consistently greater frequency of VZV in the adventitia than in the media and intima in GCA-positive and GCA Bx-negative TAs most likely reflects transaxonal transport of virus along afferent nerve fibers that innervate the TA after reactivation from ganglia [20]. In GCA-positive TAs, VZV in skip areas with inflammation is almost always associated with pathological features of GCA. The presence of VZV in skeletal muscle likely reflects the fact that the mammalian superficial TA is richly innervated and that nociception in connective tissue of the temporalis muscle is relayed by afferent fibers with cell bodies in the trigeminal ganglia from which VZV reactivates. Interestingly, about 40% of patients with GCA have a history of polymyalgia rheumatica. Since muscle biopsy is not usually performed in these patients, the frequency of VZV infection in peripheral skeletal muscle is unknown.

FUTURE OF VZV ANTIGEN DETECTION IN GCA AND TREATMENT

As with GCA pathology, VZV antigen and inflammation are usually patchy and detected in only some sections. Our research-focused evaluation is not practical for routine diagnostic work-up of TA biopsies. While immunohistochemical evaluation is worthwhile, the absence of VZV antigen in the TA does not rule out GCA or VZV reactivation since classic GCA pathology and viral antigen occur in skip lesions which may be missed in analysis.

As for treatment of GCA, no trials have yet been conducted to determine whether antivirals and steroids confer additional benefit to steroids alone. Although many GCA patients improve with steroids, reports are legion of GCA patients who relapse with corticosteroid withdrawal, and may also develop more disseminated VZV vasculopathy and die [21*,22*]. Because VZV triggers the immunopathology of GCA, antiviral treatment is likely to confer additional benefit to corticosteroids. The optimal antiviral regimen remains to be determined. We currently treat GCA with prednisone, 1 mg/kg, along with valacyclovir, 1 gm 3 times daily. If the patient improves after 4–6 weeks, we recommend tapering prednisone while continuing administration of antiviral agents for another 4–6 weeks. Long-term antiviral drugs are far less risky than long-term corticosteroids. Furthermore, if during a prednisone taper, patients’ symptoms recur or worsen, along with increases in ESR or CRP, oral antivirals should be added rather than increasing the prednisone dose. In our experience, antiviral treatment has successfully normalized symptoms and inflammatory markers. The value of our approach will have to be confirmed in large prospective studies.

VZV IN GRANULOMAOTOUS AORTITIS

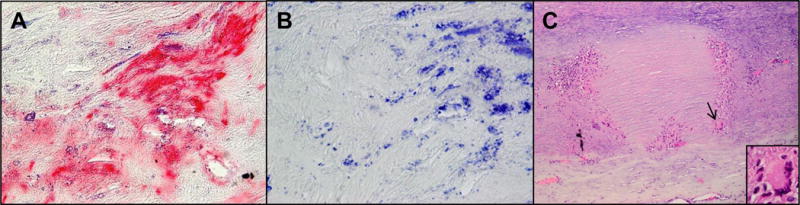

Finally, because granulomatous arteritis characterizes the pathology of GCA, granulomatous aortitis, and intracerebral VZV vasculopathy and because intracerebral VZV vasculopathy and GCA are strongly associated with productive VZV infection in cerebral and temporal arteries, respectively, we evaluated human aortas for VZV antigen and VZV DNA. Using 3 different anti-VZV antibodies, we identified VZV antigen in all of 11 aortas with pathologically verified granulomatous aortitis (Fig. 2), in one case of non-granulomatous aortitis, and in 5/18 (28%) control aortas obtained at autopsy [23]. The presence of VZV antigen in granulomatous aortitis was highly significant (P = 0.0001) as compared to control aortas, in which VZV antigen was never associated with pathology, indicating subclinical reactivation. VZV DNA was found in most aortas containing VZV antigen. The frequent clinical, radiological and pathological aortic involvement in GCA patients correlates with the significant detection of VZV in granulomatous aortitis.

FIGURE 2.

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) antigen in pathologically verified granulomatous aortitis. Immunostaining with a monoclonal mouse anti-VZV gE IgG1 antibody revealed VZV antigen in the adventitia of an aorta from a patient with pathologically verified granulomatous aortitis (A, pink color). No staining was seen when mouse IgG1 isotype control antibody was substituted for the primary anti-VZV antibody (B). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of another aorta that contained VZV antigen showed classic granulomatous aortitis pathology: inflammation in the adventitia and media with medial necrosis (C) and giant cells (C, arrow & inset). Magnification 600× (A and B) and 100× (C).

CONCLUSION

Virological analysis of TAs from patients with pathologically-verified GCA and TAs from pathologically GCA-negative patients manifesting clinical and laboratory features of GCA revealed the presence of VZV in most GCA-positive and GCA-TA Bx-negative specimens. In GCA-positive TAs, VZV was especially noted in skip areas that correlate with adjacent GCA pathology. The presence of VZV in GCA-positive and GCA-Bx-negative TAs shows that VZV triggers the immunopathology of GCA and implies the need for treatment in both groups of patients with antiviral drugs in addition to corticosteroids. It is not known whether oral or intravenous anti-viral agents plus corticosteroids are equally effective. Appropriate dosage and duration of treatment also remains to be determined.

KEY POINTS.

VZV is the only human virus shown to replicate in arteries and cause disease.

The pathology of intracerebral VZV vasculopathy and GCA is the same and characterized by granulomatous arteritis.

Productive VZV infection (herpesvirus virions, VZV antigen and VZV DNA) is seen in intracerebral VZV vasculopathy and GCA.

The number of temporal artery sections examined for VZV is critical.

The distribution of VZV in the TA and the presence of VZV in skip areas parallels the pathology in GCA.

The detection of VZV in some normal TAs indicates subclinical VZV reactivation, not VZV latency.

Because VZV likely triggers the immunopathology of GCA, antiviral treatment is likely to confer additional benefit to corticosteroid-treated patients, although the optimal antiviral regimen remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Teresa White for assistance with figure preparation, Marina Hoffman for editorial review and Cathy Allen for word processing and formatting.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported in part by NIH grants AG032958 (D.G., M.A.N.), NS093716 (D.G.) and NS094758 (M.A.N.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, are highlighted as:

*of special interest

**of outstanding interest

- 1.Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Wellish BS, et al. Varicella zoster virus, a cause of waxing and waning vasculitis: The New England Journal of Medicine case 5-1995 revisited. Neurology. 1996;47:1441–1446. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, et al. The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features. Neurology. 2008;70:853–860. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304747.38502.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salazar R, Russman AN, Nagel MA, et al. Varicella zoster virus ischemic optic neuropathy and subclinical temporal artery involvement. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:517–520. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagel MA, Russman AN, Feit H, et al. VZV ischemic optic neuropathy and subclinical temporal artery infection without rash. Neurology. 2013;80:220–222. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827b92d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathias M, Nagel MA, Khmeleva N, et al. VZV multifocal vasculopathy with ischemic optic neuropathy, acute retinal necrosis and temporal artery infection in the absence of zoster rash. J Neurol Sci. 2013;325:180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagel MA, Bennett JL, Khmeleva N, et al. Multifocal VZV vasculopathy with temporal artery infection mimics giant cell arteritis. Neurology. 2013;80:2017–2021. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagel MA, Khmeleva N, Boyer PJ, et al. Varicella zoster virus in the temporal artery of a patient with giant cell arteritis. J Neurol Sci. 2013;335:228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8**.Gilden D, White T, Khmeleva N, et al. Prevalence and distribution of VZV in temporal arteries of patients with giant cell arteritis. Neurology. 2015;84:1948–1955. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001409. The first large-scale search for VZV in archived GCA-positive TAs from 13 countries around the world. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Nagel MA, White T, Khmeleva N, et al. Analysis of varicella zoster virus in temporal arteries biopsy-positive and -negative for giant cell arteritis. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1281–1287. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2101. The first large-scale search for VZV in both archived GCA-positive and -negative TAs for VZV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilden DH, White T, Khmeleva N, et al. VZV in biopsy-positive and –negative giant cell arteritis: analysis of 100+ temporal arteries. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroiniflamm. 2016 doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000216. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouwendijk WJD, Choe A, Nagel MA, et al. Restricted varicella zoster virus transcription in human trigeminal ganglia obtained soon after death. J Virol. 2012;86:10203–10206. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01331-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor-Gjevre R, Vo M, Shukla D, Resch L. Temporal artery biopsy for giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1279–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuer GS, Nesher R, Neinus K, Nesher G. Association between histological features in temporal artery biopsies and clinical features of patients with giant cell arteritis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2013;15:271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nordborg C, Nordborg E, Petursdottir V, et al. Search for varicella zoster virus in giant cell arteritis. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:413–414. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy PG, Grinfeld E, Esiri MM. Absence of detection of varicella-zoster virus DNA in temporal artery biopsies obtained from patients with giant cell arteritis. J Neurol Sci. 2003;215:27–29. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Pla A, Bosch-Gil JA, Echevarria-Mayo JE, et al. No detection of parvovirus B19 or herpesvirus DNA in giant cell arteritis. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper RJ, D’Arcy S, Kirby M, et al. Infection and temporal arteritis: a PCR-based study to detect pathogens in temporal artery biopsy specimens. J Med Virol. 2008;80:501–505. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell BM, Font RL. Detection of varicella zoster virus DNA in some patients with giant cell arteritis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2572–2577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarez-Lafuente R, Fernandez-Gutierrez B, Jover JA, et al. Human parvovirus B19, varicella zoster virus, and human herpes virus 6 in temporal artery biopsy specimens of patients with giant cell arteritis: analysis with quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:780–782. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.025320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilden D, Nagel MA, White T, Grose C. WriteClick Editor’s Choice: Is temporal arteritis due to VZV infection? Neurology. 2015;85:1914–1915. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000475335.63503.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Nagel MA, Lenggenhager D, White T, et al. Disseminated VZV infection and asymptomatic VZV vasculopathy after steroid abuse. J Clin Virol. 2015;66:72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.03.016. An important exhaustive case study that revealed VZV in multiple organs and arteries in a patient who abused steroids. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Gilden D, White T, Galetta SL, et al. Widespread arterial infection by varicella zoster virus explains refractory giant cell arteritis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2:e125. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000125. A retrospective analysis of a patient with GCA who failed treatment with steroids and died of disseminated VZV vasculopathy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilden D, White T, Boyer PJ, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection in granulomatous arteritis of the aorta. J Infect Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw101. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]