Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with resilience among individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Methods: Qualitative analyses were conducted of the written comments that were completed as part of a cross-sectional survey of individuals with SCI living in the community. More than 1,800 mail surveys were distributed to individuals identified as having a traumatic SCI through the records and/or membership lists of 4 organizations. Four hundred and seventy-five individuals completed and returned the survey, with approximately half (48.6%; n = 231) of respondents answering the open-ended question “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about your resilience or ability to ‘bounce back’ when you face a challenge?”

Results: Analyses of these responses identified both specific resources and cognitive perspectives that are associated with perceived happiness. Responses fell within 8 general categories: resilience, general outlook on life, social support and social relationships, religion or faith in a higher power, mood, physical health and functioning (including pain), social comparisons, and resources. Nuanced themes within these categories were identified and were generally concordant with self-reported level of happiness.

Conclusion: A majority of respondents with SCI identified themselves as happy and explained their adjustment and resilience as related to personality, good social support, and a spiritual connection. In contrast, pain and physical challenges appeared to be associated with limited ability to bounce back.

Keywords: adjustment, happiness, resilience, spinal cord injury

Adjustment to spinal cord injury (SCI) has been linked to important outcomes, including morbidity, mortality, health care costs, quality of life, and community reintegration.1,2 Difficulties adapting to life with SCI correlate with high levels of emotional distress, substance abuse, and secondary conditions; self-reports of low quality of life; and increased risk for suicide.3–5 In contrast, positive adjustment is associated with being able to continue with meaningful activities and goals to achieve positive outcomes.1

From the clinician's perspective, adjustment is often equated with the readiness, including motivation and skill, to perform needed behaviors to optimize rehabilitation and functional outcomes. Adjustment is seen as a dynamic and fluid process that interacts with intrapersonal, environmental, and biological factors to influence physical and psychological health and quality of life.2,6 Increasingly, research into adjustment includes a discussion of resilience. Resilience is defined as “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress…. [It] is not a trait that people either have or do not have. It involves behaviors, thoughts, and actions that anyone can learn and develop.”7

Despite the centricity of the concepts of adjustment and resilience to rehabilitation and community reintegration, the actual adjustment and self-regulatory processes that occur after SCI remain unclear.6 Only in the past few years has real attention been given to how cognitive appraisals and coping mediate adjustment to SCI.8–10 In addition, researchers have begun to translate concepts from the field of positive psychology and to examine the importance of a fighting spirit, finding meaning, and hope in mediating the relationship between functional status and psychological well-being.8,10–12

This article describes selected findings from a cross-sectional survey of individuals in the community living with SCI. The survey was conducted as part of a larger project on successful adjustment following SCI. The objective of this study is to describe, from the perspective of individuals living with SCI, factors that they felt contributed to their resilience or ability to “bounce back” when they meet a challenge.

Methods

Survey development

As part of a larger multimethod and multisite study, a 23-item survey (eAppendix A) was developed to identify adults with SCI living in the community who saw themselves as doing well and living meaningful lives. Survey questions were developed by study investigators in collaboration with an advisory council consisting of individuals with SCI, representatives from stakeholder organizations, and health care providers. Items pertained to personal factors, current health, and access to care. Injury-related characteristics were obtained by asking respondents closed-ended questions such as level of injury, number of years living with the injury, and feeling and movement below the level of injury. Embedded within the survey were standardized scales of satisfaction with life and flourishing,13,14 as well as questions specific to happiness and resilience. Participants were asked, “Generally speaking, would you describe yourself as being happy?”, and they responded on a 5-point scale from “all the time” to “not at all.” This question has been used as a brief assessment of subjective well-being in other studies.15 Finally, participants had the opportunity to respond to the open-ended question, “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about your resilience or ability to ‘bounce back’ when you face a challenge?”

Recruitment of subjects

Study protocols were reviewed and human subject protection approvals were obtained by the funding organization and relevant institutional review boards. Survey participants were identified through medical records, membership lists, and SCI-related databases of the 4 organizations that collaborated on this project. This approach gave researchers the opportunity to reach a broad spectrum of the known population of persons with traumatic SCI in southeastern Michigan and northern Ohio.

A cross-sectional mail survey design with a 4-step approach was used. The 4 steps included sending participants: (1) a prenotification postcard; (2) a packet that included a cover letter, the survey, a return envelope, and a small ($3) incentive; (3) a reminder postcard; and (4) a second survey packet without an incentive. More than 1,800 surveys were mailed.

Data analyses

A 3-step approach to content analysis was used to uncover and interpret the responses of study participants. The first step was to examine the actual words participants used to answer the survey question; these were then used to articulate categories. Words that occur with great frequency are key to understanding survey respondents' understanding of resilience. It is essentially a quantitative technique that provides numeric counts and thus has a certain degree of precision.16,17

The second step to data analysis used a qualitative approach. For each of the categories identified, one of the authors (Duggan) examined the content of the replies provided by the survey participants—their thoughts, feelings, or actions in relation to their lives as persons living with SCI. Here the emphasis was not on frequency counts, but rather on delineating meaningful themes (central ideas) associated with the responses of survey participants. Responses were reviewed and themes were discussed with 2 of the other authors (Trumpower & Meade) before being finalized.

After categories were identified and themes articulated, we examined and grouped responses within each theme by the respondent's self-described level of happiness (happy “all” or “most” of the time, “some” of the time, “very infrequently,” or “not at all”).

Results

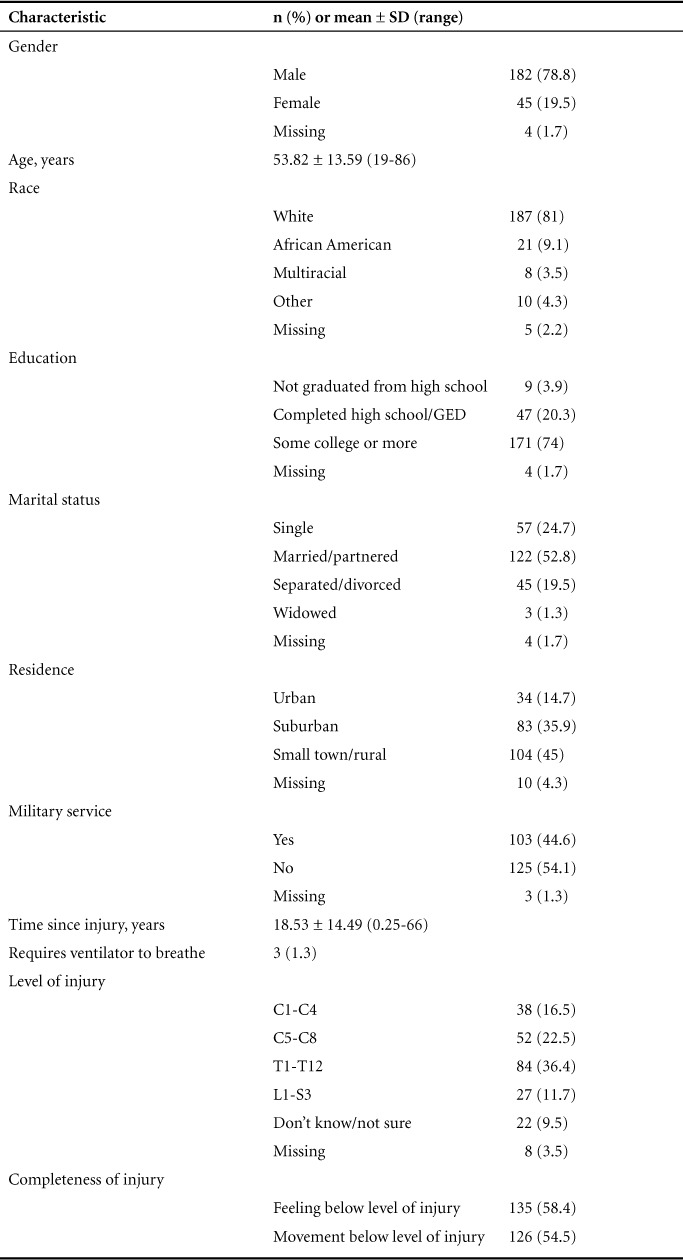

Demographic information and responses from the 231 individuals who answered the open-ended question “Is there anything else we should know about your resilience or ability to ‘bounce back’ after a challenge?” were extracted for analysis from the larger project database of 475 valid surveys. Characteristics of the sample used for this study are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample (N = 231)

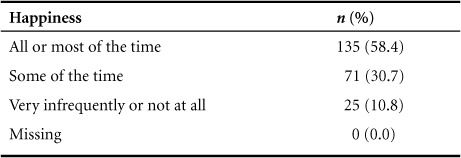

Table 2 depicts the distribution of responses to the open-ended question by level of perceived happiness. Of the 231 individuals whose data were extracted for this study, more than half (58.4%) reported being happy all or most of the time.

Table 2.

Self-reported happiness of participants (n = 231)

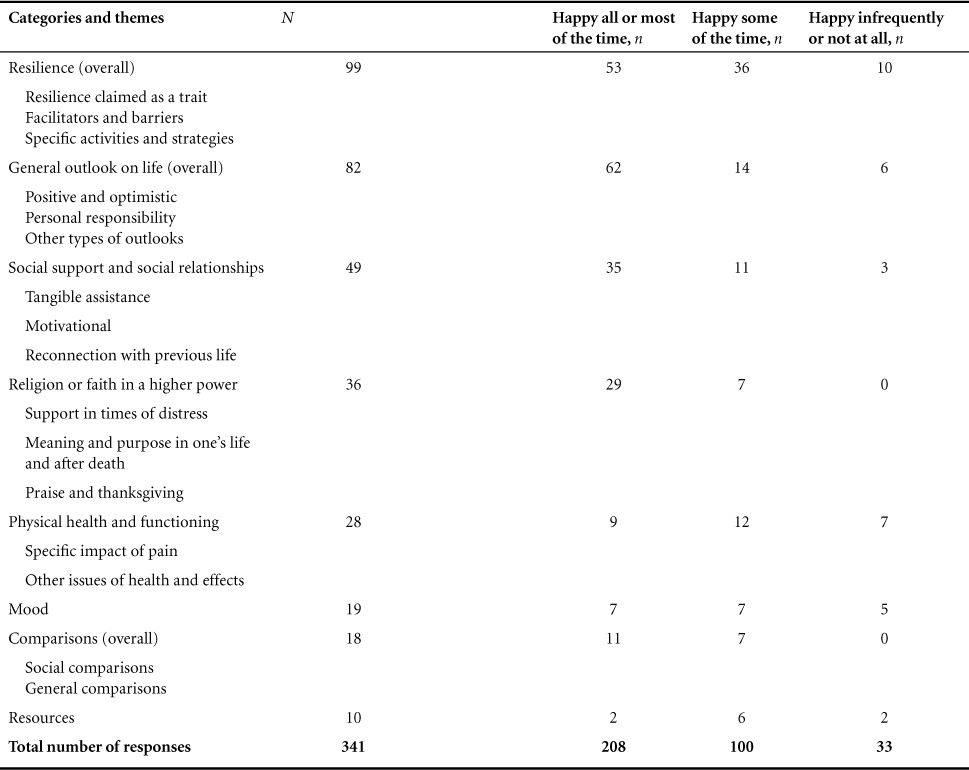

The content analysis of the responses provided by survey participants uncovered 8 distinct words or phrases directly or indirectly related to the ability to “bounce back” after SCI. Some respondents provided brief answers—a word, phrase, or single sentence. Others provided longer, more detailed responses incorporating more than one idea or theme. A total of 341 statements were identified. The qualitative analyses and articulation of the themes based on these categories are discussed below.

Table 3 shows the relationship between the frequency of responses in each category and the level of happiness. In particular, it is notable that all of the individuals who wrote about spirituality and religion and social comparisons reported being happy at least some of the time. All of the responses, grouped according to category and identified by level of happiness, are shown in eAppendix B (364.6KB, pdf) .

Table 3.

Classification of survey responses into categories and themes based on self-reported level of happiness

Resilience

The most frequent category of responses (n = 99) included words associated with resilience or similar constructs. Within this category, there were distinct themes of responses that mentioned (a) resilience as a skill or trait that individuals identified as having (or not), (b) facilitators of or barriers to resilience, and (c) specific activities and strategies—particularly cognitive restructuring—to support or achieve resilience.

The most common theme in this category was resilience as a trait. Within this theme, individuals stated:

Challenges with everyday life don't tend to stop me and I bounce back fine. Facing adversity and bouncing back is something I have done most of my life. Mentally I am very strong and have been able to make the best out of bad situations my entire life.

At the opposite end of the continuum were individuals who spoke of a lack of resilience.

I no longer face problems/challenges “head on.” Instead I hide hoping these things will blow over or just go away.

The second theme within this category pertained to facilitators of and barriers to resilience. Respondents also mentioned a variety of factors that either facilitated or impeded their ability to “bounce back” after SCI. Supportive factors included persistence, personal growth, a history of experiencing and facing adversity, and the ability to adapt to new situations. This excerpt is representative of this aspect of the theme: “It is a constant battle, but after so many years you learn to bounce back quickly.”

Barriers to resilience cited by respondents included the sheer number of years living with SCI, the aging process, the accumulation of challenges over time, the number of challenges at any one point in time, a tendency to avoid problems, chronic pain, and the belief that no one could truly bounce back after a traumatic event. Individuals who took this approach typically described themselves as happy less often.

Wish I were younger and better physically to “bounce back.” Wish I didn't tire so easily. Chronic pain makes it hard to bounce back.

Finally, a number of respondents mentioned specific activities and strategies—particularly cognitive restructuring—to support or achieve resilience:

I tell myself I'm the only one who has control of my life and can make it or break it, only me. I pull myself up by my bootstraps and move on.

I bounced back through adaptive sports and my education/career. Without them I would be miserable. My recovery was about getting back to my “normal” before injury.

I am good at compensating. If I can't do something, I looked for a new way to do it.

General outlook on life

The second most frequently mentioned category was general outlook on life (n = 82), a concept that refers to a person's point of view, attitude toward life, or expectations for the future. Within this category, themes reflected (a) positive attitude or outlook, (b) a sense of personal responsibility, and (c) a mix of other types of approaches.

Responses that reflected the theme of positive attitude or outlook were particularly evident among participants who reported higher levels of happiness. What characterized their statements was a sense of optimism—the general belief that people can accomplish anything if they put their mind to it. Also implied in their statements was a sense of purpose in life and the decision to focus more on the future and less on the past. Below are examples within this theme:

The past is behind you. Stop looking back and focus on the present (what you can do and accomplish).

Each day is a blessing—the good, bad and challenging we may face. Tomorrow is new day, a new page of life.

Purpose in life (and sheer force of will) can go a long way in overcoming major challenge.

Other survey respondents incorporated suggestions of actions or strategies they used to ensure a positive outcome, such as seeking out “new ways of doing things,” “working smarter, not harder,” and “always push for improvement—stay well-read.”

A second theme that could be seen within this category was a sense of personal responsibility. Statements appeared to reflect a sense of ownership to achieving independence or other outcomes of importance.

If you don't do it, nobody else will.

It's up to me, go backwards or forward. I'm not going backwards, have to stay positive, but it is hard. But I'm alive and my 3 girls need me. I have a whole bucket of problems, so I just put a lid on it.

In contrast, individuals who identified themselves as less happy were more likely to mention that their outlook on life had changed over the years, sometimes to the point of helplessness. These individuals often mentioned that they had been optimistic in the early years after injury, but at some point in time, the struggles they experienced were wearing them down.

I tried to be optimistic, but over the years of chronic pain, I have been worn down.

I've been known for my ability to see the good. So far I seem to be managing but just barely.

I still have moments of “Why me?”

Social support and social relationships

Social support and social relationships were frequently mentioned as part of the responses (n = 49). The majority of respondents referred to persons in their immediate environment, including family members (spouse, children, and other relatives), friends, and other individuals who impacted their life (such as medical professionals and wheelchair sports teammates), as being crucial to their ability to bounce back in response to a challenge and specifically after their SCI.

Among those who mentioned the importance of social support, many identified personal qualities or attributes of the caregiver, such as constancy, consistency, love, and willingness to support their injured relative or friend in their recovery. The following comments are typical of this group of respondents:

Good family and friends support are a huge help.

My wife's support helps; the love of my family helps.

My husband was a “rock.”

A significant number of respondents described the many ways that family and friends contributed to their ability to bounce back after SCI. Three themes appeared to be woven into these responses. The first subcategory acknowledged the importance of the tangible help of friends and family. Though specific activities were not mentioned, it was apparent from their answers that without assistance from family and friends, respondents would have had a limited opportunity to participate in activities they had valued, enjoyed, and had always done in the past. The following comments illustrate this point:

I have my down days… but thank God I'm alive and have so many people who support me in things I want to do.

Good support from friends that won't keep the chair from letting you do things.

A more frequently mentioned benefit of social support was motivational. Social support was crucial in buffering respondents from the possible onset of future crises. Social support was also helpful in encouraging respondents to be engaged in day-to-day life, thus facilitating a sense of continuity in their lives post SCI onset.

Without the support of my family and friends—would have “no drive to live” and little future. They make me strive to be better and to go a little further along life with a sure step.

I have two children that have kept me motivated not to give up.

Finally, survey participants identified the importance of reconnecting with their past life. Resuming former roles and responsibilities in the household and community provided a sense of purpose in life as well as productivity. It also provided a sense of continuity with their lives prior to injury.

Even though the deck is stacked against me, I have to keep getting up and moving forward because other people still depend on me.

I look at every day as another opportunity to be the best person I can for myself. And, more importantly, for the people around me.

Religion or faith in a higher power

Responses were notable for the inclusion of statements about religion or faith as a way of understanding and coping with the consequences of SCI (n = 36). Some responses were brief, such as “faith” (or belief in a higher power), “prayer,” or “amazing grace.” Others provided more detailed responses that gave insight into the functions of religion and faith in their lives.

Below is a sampling of respondents' statements. Three themes appear to be embedded in the comments reflecting the various functions of religion in their lives: (1) support in the time of distress, (2) meaning and purpose in one's life and (future life) after death, and (3) praise and thanksgiving.

A significant religious theme embedded in the statements of survey respondents was their dependence and trust in God and support they received from God in time of stress. The following statements are reflective of this theme:

God give[s] me the strength.

I believe in a God who knows my trials and helps me through each step. I believe that if I depend on his strength, that I can succeed no matter what level of function I have or don't have.

For some respondents, religion (or spirituality, if respondents were not members of organized religious institutions) provided a sense of purpose and meaning in their present life on earth. It was also an important source of comfort in dealing with their anticipated future life following earthly death.

My faith in God really blossomed with my SCI. I know that I am right where He wants me to be.

I am crucified with Christ, therefore I will live. Everything in this life will eventually fade—so cling to what is eternal and everything will fall into place.

The promises for our future that are in the Bible help me be positive and excited for my future. (Psalms 37:29; Revelations 21:4)

I am a born-again Christian. Even after death I have hope.

A final theme mentioned by a few respondents reflected a sense of gratitude, praise, or thanksgiving for the blessings received. These were brief comments:

Every day is a blessing.

I am truly blessed with support and God.

In summarizing this section of the report, it should be mentioned that the vast majority of respondents viewed religion and faith as functioning positively to promote resilience or the ability to cope. Only one respondent viewed religion as a possible threat. This appears evident from the following comment:

I sometimes believe it is a test from a higher power or punishment for wrongful acts.

Physical health and functioning

Twenty-eight responses addressed issues related to health and functioning as affecting the participants' ability to bounce back after a challenge. Specific health conditions related to SCI included bladder issues, impaired movement in the neck, numbness in the head and face, and spinal compression. Some respondents cited health conditions unrelated to SCI, such as cancer, heart conditions, and degenerative arthritis.

I have balance issues, given time I can pick myself up.

A theme emerged from within this category highlighting the impact of pain on resilience. Below are 2 examples:

My pain level is my main obstacle in doing just about anything. You cannot be proactive because I am constantly at the mercy of the pain.

The chronic pain makes it hard to bounce back. The pain drugs have had terrible side effects and have not worked.

Mood

In 19 responses, statements related to mood as influencing their ability to “bounce back” after SCI were present; as might be expected, these responses are fairly concordant with self-described level of happiness. Individuals who described themselves as happier generally either mentioned being happy with their lives and taking pleasure in facing adversity or in having a balance of positive and negative moods. The comments of these 2 individuals are representative:

I am happy to be alive every day.

In the seventeen years since my accident, I have never dealt with bouts of depression or anger. I take pleasure in defying the odds.

Several responses, though, were notable for a sense of despair.

I am in desperate search for a doctor supportive of assisted suicide.

The drugs used to treat my SCI have completely ruined my life. The anti-depressant used to control my nerve pain has caused severe depression that I never had before and I cannot escape from.

Comparisons

Comparisons (n = 18) also emerged as a category. Within this category, there were 2 themes: social comparisons and comparison to a more general outcome. It is notable that none of the respondents who described themselves as happy infrequently or not at all made comparison statements.

The social comparisons were almost always downward comparisons, that is, respondents were comparing themselves to people they viewed as being “worse off ” in some way than they themselves were. For the most part, these other people were not defined explicitly. Below are examples reflecting such comparisons:

Every time I've found myself at the lowest point, feeling that I can no longer deal with paralysis, I always manage to see someone worse off than me.

I know there are people worse off than I. So whenever I want to complain about things I want to do and can't, I try to remember that.

Only one respondent made what might be considered an upward comparison—a situation in which respondents viewed their lives unfavorably compared to other people with or without disabilities.

I met a “quad” who was physically much worse off than me but living his life just fine. I realized there was no reason why I could not do the same things and more.

A few respondents made more general comparisons, contrasting the current state of their lives with the way things could have been (“… things can always be worse”). Once again, these statements typically reflect that life and the current situation is better than it might be.

Resources

An eighth category emerged from responses in which a lack of access to resources or services was mentioned (n = 10), including therapy, transportation, and employment. Most of the individuals who responded in this way reported that they were happy “some of the time.”

Felt like I was bouncing back when I had regular PT. Insurance is no longer paying.

I know things could be worse. My main problem is having enough money to take care of my wife and monthly bills every month since they have cut my check down so low. It is hard for us.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to use responses to the question “What else should we know about your resilience or ability to ‘bounce back’ from a challenge?” to identify self-reported facilitators and barriers associated with adjustment and happiness following SCI. Eight categories were identified: resilience, general outlook on life, social support and social relationships, religion or faith in a higher power, physical health and functioning, mood, comparisons, and resources. These categories encompassed 18 overlapping themes that increased understanding of the factors that are related to resilience among adults with SCI living in the community. Consistent with previous research,18 the majority of respondents described themselves as being happy “all or most of the time.”

The category of resilience was the most frequently articulated in this study, likely because it was prompted by the format of the question that asked specifically about it. Respondents, though, used the opportunity to claim it as a trait or skill that they possessed to varying degrees or to provide information about barriers or facilitators (including activities and strategies) to maintaining it. The concept of resilience was clearly one that resonated with participants and is relevant to better understanding the experiences of those individuals with SCI who have been successful in adjusting to their traumatic injury and going on with their lives.19,20 The ability to be persistent, knowing how to face adversity, adaptability, personal growth, and finding meaning were all associated with “bouncingback” and are consistent with, and expand upon, existing research. In particular, they appear to overlap with the 5 factors of posttraumatic growth described by Tedeschi and Calhoun.21

The next category that was articulated was general outlook on life. In particular, most of the respondents reported a positive, optimistic approach to life concordant with their self-reported level of happiness. Responses in this category included details about the role and importance of “attitude” that have been previously cited as impacting quality of life and adjustment among individuals with SCI.22,23 Respondents also identified actions or strategies they used to have positive outcomes. Those individuals who reported a negative outlook were likely to have described this as being a change from a previous approach to life.

Social support and social relationships were also frequently mentioned as impacting resilience; a finding concordant with how physical disability and mobility impairment can have social consequences that can threaten a person's sense of connectedness to family and to the larger community. Respondents with SCI in this study were appreciative of the support they received from family and friends and described it as a positive factor in their integration back into community life and in promoting resilience. The importance of family and personal relationships has varied; some studies identified these relationships as unmet needs while others identified them as important to an individual's psychological and physical well being.24–26 This study supports the latter statement, with social relationships and social support articulated as key features of resilience.

The category of religion or faith in a higher power as a source of support was also clearly articulated by respondents and adds to the literature on adjustment to SCI. Little attention in the SCI literature has been paid to whether or not (and how) people ask for and receive support from a higher power, including spiritual forces and spiritual beings such as God.27 For most people, religion and church attendance are not the primary focus of their everyday lives.28 However, the salience of religion (or faith in a higher power), as measured by its importance and centrality in people's lives, increases for people facing health-related crises.29 The onset of SCI challenges a person's sense of personal control and is likely to trigger religious or spiritual thoughts as a way of making sense out of his or her life after SCI.30–32

The relationship between resilience and social comparisons is also not frequently discussed in rehabilitation research, though it is noted in the larger body of psychosocial research.33 Although this category of responses was one of the smaller seen, it appeared to be associated with better outcomes. Responses seem to suggest that a comparison with others who are viewed as being less fortunate (either based on resources, level of impairment, or some other factor) is an adaptive response that motivates a sense of resilience.

The other categories of responses—including those of physical health and functioning, mood, and resources—are consistent with and expand on previous research on satisfaction of life following SCI.34,35 This research shows that higher levels of distress and lower levels of life satisfaction are related to poorer health, higher levels of pain, and fewer resources.

Overall, the categories and themes articulated in this study appear to be consistent with the research supporting the use of the Stress Appraisal and Coping Model to understand adjustment following SCI. 36–39 In particular, our findings highlight the frequency that individuals with SCI perceive themselves as being happy and how this appears to be connected with self-identification as being resilient, employing strategies to reframe one's experience, and having a sense of support from friends or a higher power.

Limitations

A primary limitation of this study is self-selection bias, that is, only individuals who decided to complete the open-ended question and participate in the larger survey were included. Although the sample remains fairly large and diverse for a qualitative study, it is undoubtedly weighted to reflect the perspectives of individuals with SCI who had the energy and motivation to participate.

Implications for future research

It is important that clinicians integrate into practice not only information that is based upon studies that demonstrate statistical relationships among and between variables but also information from the narrative qualitative approach that adds an understanding of the process of “successful adjustment.” The approach of allowing individuals to reprocess and to identify new understandings and meaning for their lives after such an injury, described by the participants here, is consistent with the current procedures of many clinicians. The use of such assessment findings to inform and influence well-directed plans for treatment may require a modification or expansion of the underlying clinical framework. Continued research using the above approach to the adjustment process after SCI is needed and will allow the field to more fully identify, understand, and appreciate the positive aspects of the transformation.

Conclusions

The issue of resilience and ability to bounce back following SCI appears to be one that resonates with a significant number of individuals. Their responses reflect both supports and barriers to adjustment.

Acknowledgments

All of the co-authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report. Funding was provided through the proposal “Cognitions, Decisions, and Behaviors Related to Successful Adjustment Among Individuals With SCI: A Qualitative Examination of Military and Nonmilitary Personnel,” funded through the Department of Defense, Proposal Log Number SC110130, Award Number W81XWH-12-1-0589, HRPO Log Number A-17615.1a. Support for use of REDCap was provided through the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research grant support (CTSA: UL1TR000433).

The authors would like to thank Joanna Jennie for assisting with the preparation of the manuscript and Andrew Stewart for contributing to the review of the background research.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Edhe DM. Application of positive psychology to rehabilitation psychology. In: Frank RG, Rosenthal M, Caplan B, editors. Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards JS, Kewman DG, Richardson E, Kennedy P. Spinal cord injury. In: Frank RG, Rosenthal M, Caplan B, editors. Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.North NT. The psychological effects of spinal cord injury: A review. Spinal Cord. 1999;37(10):671–679. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinemann AW, Doll MD, Armstrong KJ, Schnoll S, Yarkony GM. Substance use and receipt of treatment by persons with long-term spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72(7):482–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanford RE, Soden R, Bartrop R, Mikk M, Taylor TKF. Spinal cord and related injuries after attempted suicide: Psychiatric diagnosis and long-term follow-up. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(6):437–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott TR. Defining our common ground to reach new horizons. Rehabil Psychol. 2002;47(2):131–143. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychological Association. FYI: Building your resilience. 2015. http://www.apapracticecentral.org/outreach/building-resilience.aspx Accessed November 30, 2015.

- 8.Chevalier Z, Kennedy P, Sherlock O. Spinal cord injury, coping and psychological adjustment: A literature review. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:778–782. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean R, Kennedy P. Measuring appraisals following spinal cord injury: A preliminary psychometric analysis of the appraisals of disability. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54(2):222–231. doi: 10.1037/a0015581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy P, Evans M, Sandhu N. Psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury: The contributions of coping, hope and cognitive appraisals. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14(1):17–33. doi: 10.1080/13548500802001801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audu ML, Nataraj R, Gartman SJ, Triolo RJ. Posture shifting after spinal cord injury using functional neuromuscular stimulation—a computer simulation study. J Biomech. 2011;44(9):1639–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfstrom ML, Smithson EF. Cognitive appraisals, coping and quality of life outcomes: A multi-centre study of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:762–769. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indicators Res. 2009;39:247–266. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolan P, Peasgood T, White M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J Econ Psychol. 2008;29(1):94–122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catanzaro M. Using qualitative analytic techniques. In: Woods NF, Catanzaro M, editors. Nursing Research Theory and Practice. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1988. pp. 437–456. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morse J. Qualitative generalizability. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(1):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonanno GA, Kennedy P, Galatzer-Levy IR, Lude P, Elfström ML. Trajectories of resilience, depression, and anxiety following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57(3):236–247. doi: 10.1037/a0029256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White B, Driver S, Warren A-M. Considering resilience in the rehabilitation of people with traumatic disabilities. Rehabil Psychol. 2008;53(1):9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White B, Driver SD, Warren AM. Resilience and indicators of adjustment during rehabilitation from a spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2010;55(1):23–32. doi: 10.1037/a0018451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siösteen A, Lundqvist C, Blomstrand C, Sullivan L, Sullivan M. Sexual ability, activity, attitudes and satisfaction as part of adjustment in spinal cord-injured subjects. Paraplegia. 1990;28(5):285–295. doi: 10.1038/sc.1990.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vissers M, van den Berg-Emons R, Sluis T, Bergen M, Stam H, Bussmann H. Barriers to and facilitators of everyday physical activity in persons with a spinal cord injury after discharge from the rehabilitation centre. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(6):461–467. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dijkers M, Abela NB, Gans BM, Gordon W. The aftermath of spinal cord injury. In: Stover SL, Delisa JA, Whiteneck GG, editors. Spinal Cord Injury. Clinical Outcomes from the Model Systems. Baltimore: Aspen: Baltimore: 1995. pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy P, Rogers BA. Reported quality of life of people with spinal cord injuries: A longitudinal analysis of the first 6 months post-discharge. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:498–503. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAweeney MJ, Forchheimer M, Tate DG. Identifying the unmet living needs of persons with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil. 1996;62:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meade M, Jackson MN, Barrett K, Ellenbogen P. Needs Assessment of Virginians with Spinal Cord Injury: Final Report: Findings and Recommendations. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallop G. Religion in America: The Gallup Report (Report No. 222) Princeton, NJ: Princeton Religion Center; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pargament KI, Kennell J, Hathaway W, Grevengoed N, Newman J, Jones W. Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of coping. J Sci Study Relig. 1988;27(1):90–104. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulman RJ, Wortman CB. Attributions of blame and coping in the “real world”: Severe accident victims react to their lot. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977;35(5):351–363. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.35.5.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duggan CH. “God, if you're real, and you hear me, send me a sign”: Dewey's story of living with a spinal cord injury. J Relig Disabil Health. 2000;4(1):57–79. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keany KC, Glueckhauf RL. Disability and value change: An overview and reanalysis of acceptance of loss theory. Rehabil Psychol. 1993;38(3):199–210. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Todd JL, Worell J. Resilience in low-income, employed, African American women. Psychol Women Q. 2000;24(2):119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Putzke JD, Richards JS, Hicken BL, DeVivo MJ. Predictors of life satisfaction: A spinal cord injury cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(4):555–561. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.31173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Putzke JD, Richards JS, Hicken BL, DeVivo MJ. Interference due to pain following spinal cord injury: Important predictors and impact on quality of life. Pain. 2002;100(3):231–242. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martz E, Livneh H, Priebe M, Wuermser LA, Ottomanelli L. Predictors of psychosocial adaptation among people with spinal cord injury or disorder. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1182–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galvin LR, Godfrey HP. The impact of coping on emotional adjustment to spinal cord injury (SCI): Review of the literature and application of a stress appraisal and coping formulation. Spinal Cord. 2001;39(12):615–627. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catalano D, Chan F, Wilson L, Chiu CY, Muller VR. The buffering effect of resilience on depression among individuals with spinal cord injury: A structural equation model. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(3):200–211. doi: 10.1037/a0024571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]