Abstract

Background: Drug shortages are a problem that has been growing in recent years. This problem has an impact on patient outcomes and public health. Most countries have been affected by a diversity of drug supply chain problems.

Objective: To assess explanations for differences in drug shortages reported in the hospital setting in Saudi Arabia (SA) and the United States (US).

Methods: Data were collected in May–June 2014 from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and from 2 Saudi hospitals: King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH) and King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSHRC). Drugs were classified using the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. The drug shortages among the hospitals were compared using descriptive statistics and a chi-square test.

Results: The percentage of the total number of active ingredients reported in shortage was higher in the US hospital setting (15.1%) than in the Saudi hospitals (10.3%) (p < .0001). KAUH reported the highest number of shortages (n = 133), followed by BWH (n = 42) and KFSHRC (n = 27). A significantly higher percentage of shortages involved injectable drugs in the US hospital setting (78.1%) than the Saudi hospitals (34.43%) (p ≤ .0001). Nervous system (17%) and alimentary tract and metabolism agents (15.7%) were the therapeutic areas with the higher number of reported shortages in the US and SA hospital settings, respectively.

Conclusions: The number and characteristics of shortages varied by country and hospital. Several factors, including differences in hospital characteristics, number and type of drugs available, and procurement systems, may explain differences in reported shortages.

Keywords: drug shortages, hospital setting, Saudi Arabia, United States

Drug shortages are not new,1,2 and they are a global problem that has been growing significantly in recent years.3,4 Gray and Manasse listed 21 countries that have been affected by a diversity of drug supply disruptions in an article published in 2012.4 In the United States (US), drug shortages have been considered a health care crisis.5 Shortages are becoming more frequent and severe, affecting all therapeutic classes.5–7 There were 211 new national drug shortages reported by the University of Utah Drug Information Service in the US in 2010, 267 in 2011, 204 in 2012, 140 in 2013, and 185 in 2014.5,8

Information about shortages in Saudi Arabia (SA) is limited. A study at a teaching hospital in SA published in 2010 found that 9% of the prescriptions that were issued during a 6-month study period were not dispensed due to drug shortages.9 Shortages occur more frequently in the supply chain of sterile injectable products, oncology medications, anesthesia drugs, nutritional supports, and anti-infective therapies.5,7,10 Many different factors contribute to the shortages, including manufacturing problems, increased global demand, changes in regulatory standards, lack of raw materials, voluntary recalls, discontinuations, and quality problems.5,11,12 The low prices of generic medications have also contributed to the occurrence of drug shortages.13

Drug shortages have a manifest impact on patient outcomes and public health.12 Shortages may lead to missed dosages, prescribing inaccuracies, dispensing and administration errors, reduced patient adherence, and an increase in health care costs.7

In spite of the importance of drug shortages and their impact on patient care, there is a lack of studies comparing shortages in the hospital settings of different countries and describing potential factors that could explain differences in shortages among different hospitals and countries.

The objectives of this study were to describe and compare drug shortages reported in selected hospitals in SA and the US in the period May–June 2014 and to discuss factors that could explain differences in drug shortages in the hospital setting in SA and the US.

There are substantial differences between SA and the US in socioeconomic characteristics, drug regulations, pharmaceutical sectors, and health care systems. The authority for ensuring compliance with drug regulations rests in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA). The US FDA is considered one of the most advanced regulatory systems in the world; the SFDA was implemented in March 2003 and is in the process of developing its regulatory functions.14

King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSHRC) is a 370-bed government-funded tertiary care and national referral hospital facility, with 21,000 patients admitted per year. It is located in Jeddah, the second largest city in SA. KFSHRC allocated $27 million for medications in 2013 and has implemented an integrated computerized system that includes drug procurement, finance, human resources, logistics, and the billing system.15 King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH) is an 845-bed government-funded tertiary care teaching hospital in Jeddah. It allocated $12.5 million for medications in 2013, and the number of admissions reached 41,000 patients.16 Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) in Boston, Massachusetts, is a private nonprofit teaching 793-bed general medical and surgical facility with more than 45,000 admissions annually. Its drug budget allocation was $110 million in 2013.17,18

DATA AND METHODS

Data for national drugs shortages were obtained from the FDA and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) databases.19,20 The FDA defines drug shortages as a situation in which the total supply of all clinically interchangeable versions of a drug are inadequate to meet the current or projected user demand, while the ASHP describes drug shortages as a supply issue that affects how the pharmacy prepares or dispenses a drug or how patient care is influenced when prescribers use alternative products.7

A convenient sample of hospitals, including the BWH in the US and KAUH and KFSHRC in Saudi Arabia, provided information about drugs that were on back order (ie, a hospital has ordered a drug and it is not readily available for purchase). However, each hospital may have different criteria to operationalize and report shortages.

The data were collected in May–June 2014, stored in Excel spreadsheets, and listed by active ingredient and dosage form. Drugs were classified using the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. Descriptive statistics were performed to describe shortages by active ingredients, route of administration, and the ATC classification system. A chi-square test was conducted to assess differences in proportions. The statistical significant level was set a priori at p ≤ .05.

RESULTS

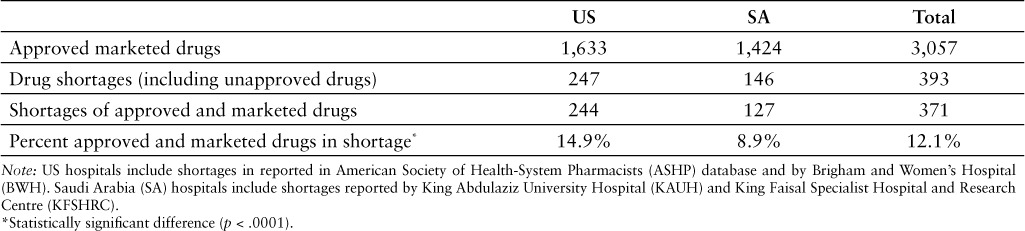

There were 247 active ingredients reported in shortage in the US hospital setting in May–June 2014 (Table 1). This number came from aggregating the shortages reported by the ASHP (n = 246) and BWH (n = 42) and then removing duplications. There were 28 shortages reported by the FDA in the same period, however FDA shortages affect drugs used in inpatient and outpatient settings and were excluded from the study. There were 3 shortages in the US hospital setting for drugs unapproved by the FDA. Furthermore, there were 146 active ingredients listed in shortage in at least one of the Saudi hospitals in the same period. KAUH reported 133 shortages and KFSHRC reported 27. There were 19 drugs unapproved by SFDA that were reported in shortage by at least one of the Saudi hospitals.

Table 1.

Percentage of active ingredients reported in shortages in a US hospital and 2 Saudi hospitals included in the study during the period May–June 2014

There were a total of 1,633 and 1,424 approved and marketed active ingredients in the study period in the US and SA, respectively (Table 1).20,21 The percentage of approved drugs in shortage was higher in the US hospital setting (14.9%) than in the 2 Saudi hospitals included in the study (8.9%) (p < .0001).

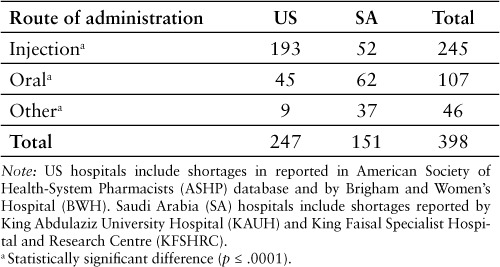

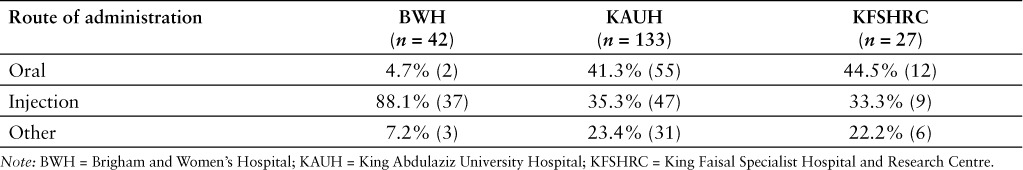

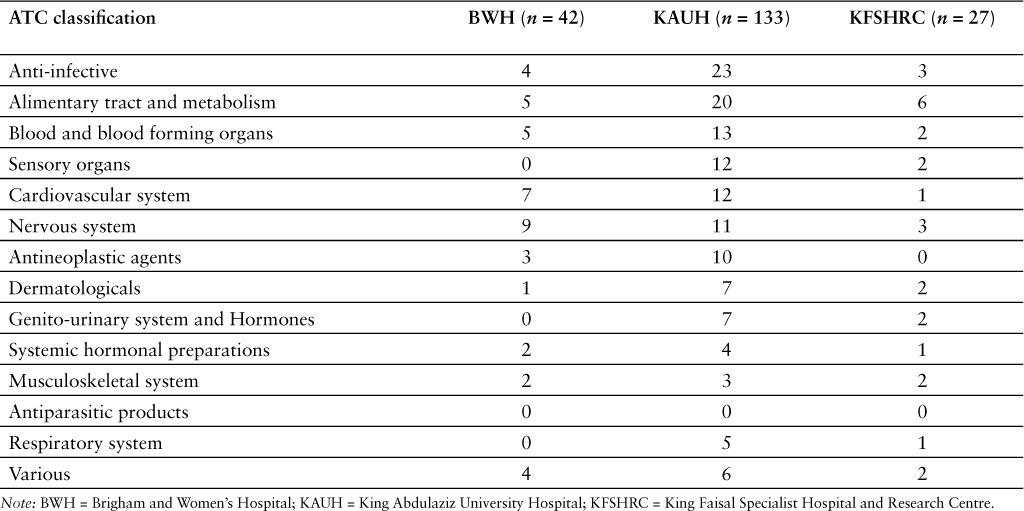

Injectable products represented most of the shortages reported in the US hospital setting (Tables 2 and 3). In contrast, oral products were more often reported in shortage in the 2 Saudi hospitals included in the analysis. The percentage of shortages corresponding to injectable products was higher in the US (78.1% of all reported shortages) than in the 2 Saudi hospitals (34.4%) (p ≤ .0001).The ATC classes with the largest number of shortages reported by BWH were nervous system (n = 9; 21.4%), cardiovascular system (n = 7; 16.7%), alimentary tract and metabolism (n = 5; 11.9%), and blood and blood forming organs (n = 5; 11.9%) (Table 4). In the case of KAUH, anti-infectives (n = 23; 17.3%), alimentary tract and metabolism (n = 20; 15.0%), and blood and blood forming organs (n = 13; 9.8%) were the classes with the largest reported number of shortages. In the case of KFSHRC, alimentary tract and metabolism (n = 6; 22.2%), anti-infective (n = 3; 11.1%), and nervous system (n = 3; 11.1%) were the classes with the largest reported number of shortages. At the same period of time (May–June 2014), there were 7 active ingredients that were reported in shortage by BWH and KAUH and another 7 that were listed in shortage by KAUH and KFSHRC. Sodium phosphate was the only active ingredient that was listed in shortage by all 3 hospitals.

Table 2.

Shortages of active ingredients by route of administration and country

Table 3.

Reported shortages by route of administration and reporting hospital

Table 4.

Shortages of active ingredients by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification and by reporting hospital

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing differences in the characteristics of the shortages reported by hospitals in 2 different countries, US and SA, with significant differences in drug regulation, pharmaceutical sectors, and health care systems. The results of the study indicate that there are differences in the number of shortages reported by hospitals in different countries and also by hospitals located in the same country. Several factors, including different criteria for operationalizing and reporting shortages, could explain the differences in the number of shortages reported by the different hospitals.

Different definitions of shortage and the criteria for reporting a shortage may exist across countries, reporting hospitals, and institutions. Differences in the number of products in shortage reported by the FDA and ASHP have been attributed to variations in the definition of shortage and the characteristics of the reporting systems.7 Differences in the incidence and characteristics of shortages can also be related to differences between SA and the US in drug regulations, pharmaceutical sectors, and health care systems.

Most shortages were reported by KAUH, followed by BWH and then KFSHRC. This difference might be attributed to several reasons. First, the drug budget allocated by each hospital for purchasing pharmaceuticals may be an important factor to explain differences in reported shortages. In the case of the Saudi hospitals included in the analysis, KAUH has a limited budget in comparison with KFSHRC. A difference in resources may have a significant impact on the ability to purchase or import drugs in short supply.

The relatively higher number of shortages found in the US hospital setting may be explained by the existence of a greater number of products available in the US market (including niche and orphan products) than in SA. The large number of niche products and specialty drugs used by a highly specialized hospital such as BWH may increase the risk of shortages, in spite of the larger budget allocated by BWH to pharmaceuticals.

The analysis at the level of the route of administration indicated that injectable was the route of administration most affected by shortages in BWH. However, in the 2 Saudi hospitals, the majority of shortages occurred in active ingredients with the oral route of administration. The reasons behind this difference may be related to the strict requirements for sterile manufacturing established by the FDA in the US; as a result, only a few companies have the capability to produce sterile injectable products in the country.11 Additionally, the importation of sterile injectable products is complex and costly and has strict regulatory requirements set by the FDA, thus reducing the possibility of the international market purchasing sterile injectable medications by US providers.

With the exception of antiparasitic products, drug shortages affected all therapeutic classes. In the US hospital setting, the largest number of shortages occurred in the classes of nervous system, anti-infectives, and cardiovascular system. In the 2 Saudi hospitals, shortages were more frequent in the classes of alimentary tract and metabolism agents and anti-infective medications. Differences in classes may be explained in part by the routes of administration used. Anti-infective drugs, for example, may have a larger number of injectable products in comparison with other classes.

The existence of only one active ingredient reported in shortage across all the hospitals assessed in the study was an unexpected result. However, this result indicates that shortages can occur at a micro level and that hospitals located in the same city may have different drugs in shortage.

This study has some limitations. We compared the number of drug shortages between the US and SA hospital settings during a relatively short period of time (May–June 2014). Expanding the analysis over a longer period of time may result in finding more similarities in shortages and potentially more shortages that occur across countries and hospitals.

Furthermore, the study only included one hospital in the US and 2 hospitals in SA, thus the results of the analysis cannot be generalized to other hospitals in these countries. There is no standard definition in the US and SA health care systems for identifying and reporting drug shortages. Additionally, assessing differences in shortages between these countries is difficult due to the lack of any national organization or institution reporting shortages in SA. In contrast, 2 main organizations, one public (FDA) and the other a nonprofit (ASHP), report shortages that occur in the country. Therefore, the interpretation of the p values must consider the differences between definitions, hospitals' characteristics, and regulatory systems. However, this is an exploratory analysis that aims to discuss differences in factors affecting drug shortages in the US and SA and not to generate results that could be generalizable to all hospitals. This study provides an estimation of the number of drugs in shortage. Future research should assess the impact of shortages on patient care at the level of each hospital.

CONCLUSIONS

Differences exist in the number and characteristics of drug shortages reported by hospitals in different countries and also by hospitals located in the same country. Several factors could explain the variation found in this study, including differences in definitions of shortage, budgets allocated to purchasing of pharmaceuticals, regulatory systems, and the mix of drug products used in each country and hospital. Results also indicate that shortages can be occurred at a micro level, with hospitals located in the same city reporting a set of different drugs in shortage.

There is a need for a standard definition of drug shortage that could be applicable across countries, reporting organizations, and hospitals. Such a definition will allow for a better understanding of the problem of drug shortages and assessment of the impact of policies aiming to reduce the clinical and economic impact of drug shortages.

Future studies could expand the sample to other hospitals in both the US and SA to generalize the result of the analysis to the hospital setting in each country. Moreover, further studies could assess the reasons for shortages and the prevalence of shortages as a proportion of the drugs listed in the formulary of each hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deutschmann W. Supply shortages in Germany. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2004;10(6):144–145. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodend AK, Poston J, Weir K. Drug Shortages—Risk or reality? Can Pharm J. 2005;138(1):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kweder SL, Dill S. Drug shortages: The cycle of quantity and quality. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;93(3):245–251. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray A, Manasse HR., Jr Shortages of medicines: A complex global challenge. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(3):158. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.101303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox ER, Sweet BV, Jensen V. Drug shortages: A complex health care crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(3):361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Executive order 13588 – Reducing prescription drug shortages. The White House website. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/10/31/executive-order-reducing-prescription-drug-shortages. Published October 31, 2011. Accessed May 2, 2014.

- 7.Le P, Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R et al. The prevalence of pharmaceutical shortages in the United States. J Generic Med. 2011;8(4):210–218. [Google Scholar]

- 8.University of Utah Drug Information Service Current drug shortage statistics [data on file]. September 30, 2015.

- 9.AL-Aqeel SA, AL-Salloum HF, Abanmy NO, Al-Shamrani AA. Undispensed prescriptions due to drug unavailability at a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Res. 2010;3(4):213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBride A, Holle LM, Westendorf C et al. National survey on the effect of oncology drug shortages on cancer care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(7):609–617. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaakeh R, Sweet BV, Reilly C et al. Impact of drug shortages on U.S. health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(19):1811–1819. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balkhi B, Araujo-Lama L, Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R, Szeinbach SL, Fox ER. Shortages of systemic antibiotics in the USA: How long can we wait? J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2013;4(1):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alsager S, Hashan H, Walker S. The Saudi Food and Drug Authority: Shaping the regulatory environment in the Gulf Region. Pharmaceutical Med. 2015;29(2):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen V, Rappaport BA. The reality of drug shortages—the case of the injectable agent propofol. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(9):806–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1005849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. About us. King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre website. Published 2013. http://www.kfshrc.edu.sa/wps/portal/en/!ut/p/c0/04_sb8k8xllm9msszpy8xbz9cp0os_jqeh9nsyddrwn33wa3a09d_1bxc2cja4mqe_2cbedfakzdrrq!/?wcm_portlet=pc_7_utoc9b1a0gmpf0i1oue7c20032_wcm&wcm_global_context=/wps/wcm/connect/kfshrc_lib/kfsh_bp/about/kfsh_rc+profile/introduction/ceo+statement. Accessed Oct 24, 2014.

- 16. About Hospital. King Abdulaziz University website. Updated January 30, 2014. http://hospital.kau.edu.sa/content.aspx?Site_ID=599&lng=EN&cid=38308. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- 17. About Brigham and Women's Hospital: The history of Brigham and Women's Hospital. Brigham and Women's Hospital website. Updated July 20, 2014. http://www.brighamandwomens.org/About_BWH/about_us.aspx. Accessed Oct 19, 2014.

- 18. Hospitals. Brigham and Women's Hospital. Stats & services. US News and World Report website. http://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/area/ma/brigham-and-womens-hospital-6140215/details. Accessed October 19, 2014.

- 19. Drug databases: Drug shortages. Current and resolved drug shortages and discontinuations reported to FDA. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm. Accessed May 2, 2014.

- 20. Drug Shortages: Current shortages. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists website. http://www.ashp.org/menu/DrugShortages/CurrentShortages. Accessed May 2, 2014.

- 21. Drug. Human drugs. Saudi Food & Drug Authority website. http://www.sfda.gov.sa/en/drug/search/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

- 22. Drugs@FDA Data Files. US Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed October 19, 2014.