Abstract

Despite the ongoing prevalence of marital distress, very few couples seek therapy. Researchers and clinicians have increasingly been calling for innovative interventions that can reach a larger number of untreated couples. Based on a motivational marital health model, the Marriage Checkup (MC) was designed to attract couples who are unlikely to seek traditional tertiary therapy. The objective of the MC is to promote marital health for as broad of a population of couples as possible, much like regular physical health checkups. This first paper from the largest MC study to date examines whether the MC engaged previously unreached couples who might benefit from intervention. Interview and survey data suggested that the MC attracted couples across the distress continuum and was perceived by couples as more accessible than traditional therapy. Notably, the MC attracted a substantial number of couples who had not previously participated in marital interventions. The motivational health checkup model appeared to encourage a broad range of couples who might not have otherwise sought relationship services to deliberately take care of their marital health. Clinical implications are discussed.

It has been well established that most married couples experience deterioration in their relationship. Roughly half of all people in the United States marrying for the first time are projected to divorce, a statistic that has remained stable over the last 20 years (National Center for Family & Marriage Research, 2009). Research consistently suggests that marital distress and dissolution are linked to higher rates of mental disorders, compromised immune system functioning, and child emotional and behavioral problems (Berger & Hannah, 1999). Fortunately, meta-analyses of the existing treatment outcome literature support the efficacy of marital therapy, with an effect size of .84 (Shadish & Baldwin, 2003). Unfortunately, the vast majority of people suffering from relationship difficulties do not seek help (Johnson, Stanley, Glenn, et al., 2002), and those who do primarily seek assistance in physicians’ offices (Russell, 2010).

What prevents couples in need from seeking available therapeutic interventions? Many couples appear to regard marital therapy as unnecessary. They may be unaware of risk factors in their relationships, failing to seek services even as their “symptoms” multiply (Doss, Atkins & Christensen, 2003). Couples who have not yet begun to self-evaluate as distressed often have low motivation to seek treatment. On the other hand, severely distressed couples often believe their relationship is too far-gone to benefit from help (Wolcott, 1986). Thus, couples in need are often caught in the paradox of either believing that their relationship is too distressed or not distressed enough to benefit from existing treatments.

Other frequently cited barriers include the cost of treatment, lack of confidence in the outcome, a preference to solve problems on one’s own, and logistical challenges such as lack of time or childcare (e.g. Uebelacker et al., 2006). Negative attitudes toward help seeking are particularly strong barriers to underrepresented groups including men (e.g. APA; Penn, Schoen & Berland Associates, 2004, as cited in Anker, Duncan & Sparks, 2009; Roberson & Fitzgerald, 1992). Several recent papers have called for the development of nontraditional marital interventions that are more accessible to a greater number of couples in need (e.g., Doss, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2009).

The Marriage Checkup

A primary goal of the Marriage Checkup (MC) is to engage couples across all levels of marital functioning, including those who have not sought psychological services in the past.

Advertising to prospective couples for the MC study involved highlighting four unique characteristics of the intervention. First, the MC is designed to be the marital health equivalent of annual physical or dental health checkups, providing an opportunity for all couples to care for the health of their marriage. Until now, marital interventions have consisted primarily of relationship education workshops or tertiary therapy for significantly distressed couples. In an attempt to fill the gap, the MC offers all married couples an opportunity to receive an individualized check up of their relationship health: satisfied couples can seek an MC prophylactically, couples experiencing mild to moderate distress can address issues before they become severe and without having to self-evaluate as “unhappy,” and highly distressed couples who might not otherwise seek tertiary therapy can be further motivated to pursue more extensive services. The second highlighted characteristic of the MC is that it is not described as therapy. Participants are informed that they will receive assessment and feedback with a trained consultant as an informational marital health service. This is intended to attract participants who may be suspicious or dismissive of marital therapy. Third, the MC is brief, consisting of a few questionnaires and two in-person visits, repeated annually. The brevity of the MC diminishes economic and time barriers and requires less confidence in the institution of therapy (i.e. can be tried on a short-term basis). This also reassures skeptical couples that the MC requires nothing of them beyond the assessment and feedback sessions. Fourth, MC advertising makes clear that the couple is responsible for deciding what, if anything, to do with the information provided. Active and autonomous participation from the couple is encouraged at all phases of the MC to promote couples’ sense of self-efficacy for their own marital health.

Following recruitment, MC couples receive an Assessment session consisting of questionnaires and an in-person, conjoint interview. The questionnaires assess for variables associated with marital deterioration, including intimacy, communication, finances, sex, coparenting, etc. Partners are also asked to identify their most significant strengths and their most pressing areas of concern. The in-person Assessment session begins with a short interview about how the couple met and decided to marry, and then guides the couple through a social support exercise and a problem solving discussion, with the therapist as an observer. The session concludes with a therapeutic interview, which prompts the couple to discuss their most significant strengths and their primary areas of concern. Reviewing their strengths reinforces the positive qualities of the couple’s relationship and sets a positive tone for the session. The discussion of the couple’s concerns uses techniques from Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT; Jacobson & Christensen, 1996) to reframe issues in terms of their “softer” emotional content, to compassionately understand reasons underlying the partners’ points of contention, and to recognize how the partners may have come to feel stuck in a mutual trap. In the current study, the Assessment session also included a brief interview about the couples’ “Reasons for Seeking an MC,” as described below.

The third and final phase of the MC is the motivational Feedback session conducted two weeks after the Assessment session. The information gathered during assessment is consolidated into a feedback report that serves as the centerpiece of the in-person Feedback session. The MC therapist guides the couple through the report which summarizes the couple’s history, reviews their strengths, lists their questionnaire scores and interpretations, and addresses their areas of concern. During this process, the therapist solicits feedback from the couple regarding the accuracy of the general interpretations and presents partners with a menu of suggestions based on the current treatment and research literature for how they might actively address their specific issues. The clinician and the couple work together collaboratively to develop individualized action plans for how to best address the issues at hand. At the end of the session, each partner receives a copy of the Feedback report updated to reflect the work during the session.

Based on Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002), the goal of the feedback session is to provide partners with objective information about their strengths and concerns in order to motivate them to take deliberate care of their marital health. The MC uses MI to facilitate partners’ movement through the successive stages of change toward behavioral activation (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). MC couples’ existing strengths are highlighted to reinforce their own ability to take care of their relationship. Areas of concern are discussed empathically yet objectively by noting discrepancies between the long-term effects of detrimental patterns versus the partners’ relationship goals. The key to a successful Marriage Checkup is to activate the couple in the service of their own marital health. MC therapists are clear that the only efforts that benefit the relationship are those each partner is individually motivated to make. (Further description of the MC can be found in Córdova, Scott, Dorian, et al., 2005; Córdova, Warren, & Gee, 2001; Gee, Scott, Castellani, & Córdova, 2002; and Morrill & Córdova, 2010).

Current Aims

This first paper from the current study aims to evaluate the ability of a marital health checkup model to attract couples across the spectrum of marital functioning, as well as couples who may not otherwise seek services. Participant interviews and self-report surveys were examined to investigate the following hypotheses: 1) The MC will attract couples who do not explicitly perceive their relationship as distressed; 2) The MC will attract couples who would not otherwise seek traditional tertiary couple therapy; 3) MC couples will have a broader range of relationship functioning than couples seeking traditional therapy; and 4) The MC will be perceived as having fewer barriers to participation than traditional therapy.

METHOD

Married couples were recruited from the metropolitan area of a large city in the northeastern United States using print and broadcast media, flyers, the Internet, and word of mouth. Those who contacted the study (N = 334 couples, 668 individuals) were screened for eligibility. The MC study used deliberately broad inclusion criteria to facilitate a naturalistic sample of all married couples interested in a marital health checkup. Couples were only excluded if they were not currently married (7 couples), married but not living together (1 couple), currently participating in couple therapy (19 couples), or in individual therapy for couple issues (7 couples). Thirteen additional couples did not participate because they were not interested, lived too far away, or were lost to contact. The 574 remaining individuals (86%) were mailed packets of questionnaires and 443 participants or 77% (214 males and 229 females) returned the questionnaires to the study. Two hundred and fifteen couples (75%) returned both partners’ questionnaires and these couples were randomly assigned to either the treatment (113 couples) or control group (102 couples) of the MC study.

Participants

The 443 partners who returned the questionnaires ranged from 20 to 78 years old with an average age of 45.7 years (SD = 11.2). They had been married on average for 15.1 years (SD = 12.0), the longest marriage being 56 years and the shortest being 22 days. Ninety-four percent of these MC treatment seekers were White, 2.5% were Black, 2.5% were Asian, and .7% were American Indian and Alaska Native. On average, couples had two children, and a household income between $75,000–99,000. Eighty-eight percent of participants were high school graduates, and 43.9% held a bachelor’s degree or higher. Seventy-nine percent of treatment seekers were employed (75.4% full-time, 24.1% part-time).

Measures

In addition to the demographic information, the questionnaires that were returned by the 443 participants collected multiple domains of relationship health data, including marital functioning as measured by the Marital Satisfaction Inventory – Revised, Global Distress Scale (MSI-R GDS; Snyder, 1997). The MSI-R GDS is a well-validated subscale measuring overall relationship distress. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the GDS was .93. Standardized mean T-scores are grouped by sex into the following categories: scores between 39–49 indicate low distress, 50–59 indicate moderate distress, and 60 and above indicate severe distress. MC participants’ MSI-R GDS scores were analyzed and compared to the scores of both community and clinical samples used in the original validation study of the MSI-R (Snyder, 1997).

The 215 randomized couples were also mailed the Mental Health Utilization questionnaire (MHU, developed for this study), which assessed their lifetime utilization of a variety of mental health treatment services. The MHU also asked about participants’ decision to participate in the MC instead of traditional couples therapy; respondents could endorse any of eight listed response options (see Table 4), and/or write-in an open-ended “Other” response. Seventy-six percent of participants (325 of 430) completed and returned the MHU and “Other” responses were given by 137 participants. All of the “Other” responses were coded by the first author, and 20% were coded separately by another trained coder, with 98% inter-observer agreement.

Table 4.

Self-report survey: Why did you choose to participate in the Marriage Checkup instead of traditional couples therapy? Please check ALL that apply:

| Reasons listed | # times endorsed | % participants endorsed |

|---|---|---|

| 1) We didn’t feel the need for therapy | 176 | 54.2% |

| 2) We didn’t know how to find a couples therapist | 8 | 2.5% |

| 3) We were uncomfortable with the idea of seeking therapy | 16 | 4.9% |

| 4) We didn’t have the time for couples therapy | 27 | 8.3% |

| 5) Couples therapy was too expensive | 31 | 9.5% |

| 6) We had a negative experience with couples therapy in the past | 15 | 4.6% |

| 7) One of us was not willing to go to couples therapy | 34 | 10.5% |

| 8) Other (please write in): | 142 | 43.7% |

Note. 325 participants (treatment and control). Responses given to 8) Other are the self-report columns coded in Table 2

Interviews

The 113 randomized treatment couples were invited for an in-person MC Assessment session which included a “Reasons for Seeking an MC” interview. Participants were asked, “Tell me a little bit about why you would like to get a Marriage Checkup at this time;” “Tell me a little bit about how, logistically, you decided as a couple to get a marriage checkup,” and “How do you hope to benefit from your Marriage Checkup?” Responses to the first and third questions were coded by five trained graduate students into categories of responses. Twenty percent of the coded interviews were double-checked by another set of blind coders and assessed for inter-rater reliability (IRR) with Cohen’s kappa. The 11 categories with fair to excellent kappas are listed in Table 1. Rarely endorsed items for which Cohen’s kappas could not be calculated were not included, nor were codes with low kappa scores. The mean reliability coefficient for the 11 items was .62.

Table 1.

Cohen’s Kappas and Number of Instances for Reasons Given for Seeking a MC

| Reason | Cohen's Kappa | Number of Instances |

|---|---|---|

| “Funtresting” | .79 | 72 |

| Relationship enhancement | .42 | 40 |

| Altruism | .42 | 38 |

| Money | .79 | 32 |

| Learn about relationship | .55 | 82 |

| MC health rationale | .79 | 70 |

| Quality time | .44 | 15 |

| Fewer barriers | .63 | 28 |

| Not distressed enough for therapy | −.05 | 2 |

| Don't know/not sure | 1.00 | 13 |

| Veiled treatment seeking | .25 | 93 |

| Like therapy, want more | N/A | 10 |

| Overt treatment seeking | .70 | 76 |

| No benefit | N/A | 8 |

| Included gay couples | N/A | 5 |

| Total | 584 |

N=198 treatment participants (99 couples). N/A indicates item was not endorsed by both coder & reliability-checker in the 20 double-checked interviews so Kappas could not be calculated. Grey shading indicates excluded items.

Only Veiled Treatment Seeking was included despite a reliability level below fair (.40). The low IRR was likely due to the ambiguous nature of the category itself, however the concept of Veiled Treatment Seeking remained particularly relevant to couple help seeking. The Veiled category encompasses statements implying relationship concerns that are not being openly admitted. Responses coded as Veiled Treatment Seeking included, “to create a forum for dialogue,” “to correct anything that needs to be corrected,” and “to understand what’s going on inside each other.” Veiled statements often appeared intentionally vague to avoid explicitly stating concerns, and thus were inherently difficult to judge as reliably as other items by definition.

The “Reasons for seeking an MC” responses were coded into the following categories (paraphrased responses from couples in parentheses): 1) “Funtresting” (“Because it sounded fun/neat/interesting”); 2) Relationship enhancement (“I don’t think there is anything wrong in the marriage, but we can always improve”); 3) Altruism (“Contribute to research”); 4) Money (“Get paid”); 5) Learn about relationship (“Gain information”); 6) MC health rationale, statements that endorse the marital health model (“A way to keep our relationship healthy”); 7) Quality Time (“Productive time together”); 8) Fewer Barriers (“It seemed easy”); 9) Don’t know/Not sure (“Nothing specific”); 10) Veiled Treatment Seeking (“Opportunity to discuss things”); and 11) Overt Treatment Seeking (“Concerned about relationship problems”). Each conceptually unique element of participants’ statements was coded separately.

Of the 113 randomized treatment couples invited for an in-person Marriage Checkup, twelve elected not to attend, citing reasons such as living too far away, being too busy, or the husband deciding not to participate. These 12 couples did not differ significantly from the 101 couples who completed the face-to-face visit on MSI-R GDS scores (t(221)=1.09, p=.28), nor length of marriage (t(25.40)=1.10, p=.28). However, they were significantly older (t(221)=2.28, p<.05), had fewer years of schooling (t(221)=−2.80, p<.01), and their household income trended toward being lower (t(26.52)=−1.97, p=.06). Of the 101 remaining treatment couples, 99 couples’ (198 participants) assessment sessions were successfully recorded (two couples’ videotapes were unable to be coded due to recording errors).

Given the similarity of the in session Reasons interview responses and the MHU “Other” responses, both modalities were coded using the same categories to facilitate direct comparison.

RESULTS

Hypothesis 1 – The MC will attract couples who do not explicitly perceive their relationship as distressed

As shown in Table 2, the top five reasons given for seeking a MC were 1) Veiled treatment seeking (47%), 2) Learn about relationship (41.4%), 3) Overt treatment seeking (38.4%), 4) “Funtresting” (36.4%), and 5) MC health rationale (35.4%). The same five (although in slightly different order) were given by both men and women.

Table 2.

Interview vs. Self-Report Most Common Reasons for Seeking an MC

| Interview Reason – 198 treatment participants (99 couples) | % Participants from interview | Number of instances | Self-Reported Reason – 73 treatment participants | % Participant s from self-report | Number of instances | Self-Report Reason – 137 treatment and control participants | % Participant s from self-report | Number of instances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veiled treatment seeking | 47.0 | 93 | Funtresting | 21.9 | 16 | Funtresting | 24.1 | 33 |

| Learn about relationship | 41.4 | 82 | Altruism | 20.5 | 15 | Altruism | 19.7 | 27 |

| Overt treatment seeking | 38.4 | 76 | Veiled treatment seeking | 19.2 | 14 | Veiled treatment seeking | 13.1 | 18 |

| Funtresting | 36.4 | 72 | Learn about relationship | 12.3 | 9 | MC health rationale | 11.7 | 16 |

| MC health rationale | 35.4 | 70 | Money | 9.6 | 7 | Learn about relationship | 10.2 | 14 |

| Enhancement | 20.2 | 40 | Overt treatment seeking | 8.2 | 6 | Money | 8.8 | 12 |

| Altruism | 19.2 | 38 | MC health rationale | 6.8 | 5 | Fewer barriers | 8.8 | 12 |

| Money | 16.2 | 32 | Fewer barriers | 6.8 | 5 | Overt treatment seeking | 5.1 | 7 |

| Fewer barriers | 14.1 | 28 | Enhancement | 2.7 | 2 | Don't know/Not sure | 2.2 | 3 |

| Quality time | 7.6 | 15 | Don't know/Not sure | 1.4 | 1 | Enhancement | 1.5 | 2 |

| Don't know/Not sure | 6.6 | 13 | Quality time | 0 | 0 | Quality time | 0 | 0 |

| Total number of instances | 559 | Total number of instances | 80 | Total number of instances | 144 |

The most frequent answers on the MHU were similar to those from the interviews, although “Funtresting” was the most common response, Overt treatment seeking was 6th, and the MC health rationale was 7th. When including control participants’ self-report surveys, four of the five top responses remained the same as the Reasons interview responses, however Altruism was again reported more frequently and Overt Treatment Seeking fell to 8th. Overall, 69.8% of responses given during the Reasons interview were non-distressed (nor Veiled) reasons for seeking an MC. Seventy-five percent of the treatment participants written-in Other responses fell in non-distressed categories, and 82.6% of reasons were non-distressed when combining control and treatment self-reported responses.

Several MC participants’ statements given during the interviews demonstrated that they did not self-identify as highly distressed in their marriage.

…Like [husband] said, we both feel that we have a good marriage and we just want to keep it that way. (Wife)

It just sounded really interesting. I feel like we’re in a really good place, but we could always get to a better place. (Wife)

As noted above, the Veiled treatment seeking findings should be considered cautiously given the reliability of the code. However, Veiled was consistently in the top three reasons for all methods of report (questionnaire and interview, and for both sexes). Several MC participants self-identified as relatively happy in their marriage, but implied veiled concerns, and also suggested how the MC provided them a rationale to participate despite their “satisfied” status.

I think our marriage is in pretty good shape but it doesn’t hurt to check and see where we stand…. And see what we need to work on and improve. (Husband)

It’s not that we don’t communicate, but there are some subjects we’re both careful about, and I would like to take that out of our relationship or at least open it up so we can look at it a little clearer.... (Wife)

By way of comparison, Doss, Simpson, and Christensen (2004) surveyed the main factors that led their 147 distressed couples to seek tertiary therapy. Four of the top five reasons given would be categorized in our system as overt treatment seeking (emotional affection, communication, divorce/separation concerns, arguments/anger) with one possibly classified as veiled treatment seeking (improve relationship). Out of the 18 rank-ordered categories of reasons given, only two would be coded by us as non-distressed: positive ideation (love for spouse, save good part of marriage; ranked 10th and given by 22% of couples), and social activities/time together (ranked 13th and given by 8% of couples). No couples reportedly endorsed seeking therapy because it seemed fun or interesting.

In contrast, MC participants talked about viewing the intervention as enjoyable.

I thought it’d be fun. No seriously. I’m serious! (Husband)

She approached me with it and it sounded fun and interesting. (Husband)

Hypothesis 2 – The MC will attract couples who would not otherwise seek traditional tertiary couple therapy

As displayed in Table 3, 63.7% (207) of respondents had never sought couple therapy before the MC, and 46.8% had never participated in individual therapy. One hundred and six participants, or 32.6%, reported they had never sought any kind of mental health treatment before the MC.

Table 3.

Previous mental health treatment seeking by percentage of participants

| Type of Previous Mental Health Treatment | % |

|---|---|

| Couples Therapy | 36.3 |

| Individual Therapy/Counseling | 53.2 |

| Group Therapy (led by a therapist) | 8.3 |

| Family Therapy | 12.3 |

| Medications only (short sessions, largely focused on medication) | 15.4 |

| Day Treatment | 2.5 |

| Hospitalization | 3.4 |

| Residential Treatment | .6 |

| Self Help (i.e., AA, NA, OA, ACOA, ALANON, Dep.Manic-Dep Assoc., etc) | 10.2 |

| Primary Care Physician (for mental health) | 12.0 |

| I have not sought any kind of mental health treatment in the past | 32.6 |

N= 325 participants

Many MC participants indicated that part of their decision to seek an MC was their belief that it was different from traditional therapy.

Well it said checkup, not necessarily therapy. (Husband)

…The idea of a check up and the way it was presented seemed more relaxed. (Husband)

It seemed interesting and non-threatening, less like a counseling kind of situation…. (Wife)

Sometimes MC couples said they would not be willing to attend traditional therapy.

We don’t really have problems I would actually consider going to therapy for but I was like, that’s kind of a neat idea, and that’s all. (Wife)

I wanted to discuss issues without therapy. (Husband)

Although the number of participants who had previously sought therapy is not usually included in published couple therapy studies, Doss et al. (2003) reported that 56% of their 147 distressed couples had attended couple therapy before with their current partner (more could have attended couple therapy with previous partners). Only 36.3% of MC couples indicated they had ever participated in couple therapy.

Additionally, as displayed in Table 4, 54.2% of MC participants indicated that they “did not feel the need for therapy,” 10.5% reported that one partner was not willing to attend couple therapy, and 4.9% were uncomfortable with the idea of seeking therapy. In addition, 9.5% responded that couple therapy was too expensive, and 8.3% said they did not have time for traditional couple therapy.

Although roughly 23% of men initiated contact with the MC, this is not very different from men in tertiary treatment samples (e.g. Doss et al., 2003). However, anecdotal evidence suggested that some men were particularly drawn to the MC.

I saw the ad in the paper and it sounded along the lines of what I was thinking of what makes our relationship tick…without it being a true counseling session. Because I never thought we needed counseling anyway…. (Husband)

I think I was pretty agreeable to it, and curious and interested…. So I was pretty receptive to it and when she showed me the paper it sounded interesting and intriguing. (Husband)

My husband saw the ad, and thought it was a good idea. (Wife)

Hypothesis 3 – MC couples will have a broader range of relationship functioning than couples seeking traditional therapy

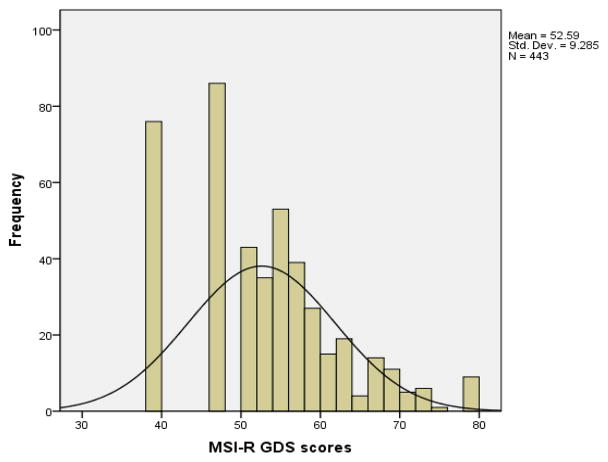

Of the 443 MC respondents, 162 had MSI-R GDS scores in the low distress (i.e. satisfied) range, 197 had moderately distressed scores, and 84 scored in the highly distressed range. Replicating findings from a previous study (Córdova et al., 2005), we compared the MSI-R GDS means and standard deviations to those reported by Snyder (1997) for 100 therapy couples (M= 64.9, SD=6.9) and 154 community couples (M=47.4, SD=7.8), used to develop norms for the MSI-R. T-tests revealed that the mean GDS score for the MC sample (M= 52.59, SD=9.29) was significantly lower than the mean couple GDS score in Snyder’s therapy sample, t(657)=−16.77, p<.001) and significantly higher than the mean couple GDS score in Snyder’s community sample, t(731)= 8.29, p<.001).

Additionally, MC couples’ GDS scores had broader overall variability than that of community or therapy couples. The variance of MC couples (86.30) was significantly larger than both the variance of community couples (60.84) and of therapy couples (47.61) at levels of p < .001. The GDS scores of MC couples spanned the entire range from 39–79 (most satisfied possible score to most distressed possible score). The mean and median GDS of 53 placed these couples just in the moderately distressed range. However, the mode of 47 indicated that the most frequent MC couple score was in the satisfied range (the second most frequent score was 40). The histogram presented in Figure 1 displays the distribution of the GDS scores, which depicts both significant numbers of couples with non-distressed scores, as well as equal overall coverage of the distressed range from means of 50 and above.

Figure 1.

Distribution of MSI-R GDS scores for 443 MC treatment seekers

In addition to the many non-distressed statements made by MC couples, other participants did express significant strain on their relationship, and stated why they believed the MC would be useful for them.

Because there has been a lot of BS the past year. I think we could actually use it. (Wife)

We were going through a hard time. I looked at counseling and this seemed like a good first step. (Wife)

We’ve been in this relationship a long time and I don’t think we’ve progressed in certain areas and to me it’s a little frustrating….We’ve tried to work it out amongst ourselves the best we can…. So we’d welcome any feedback. (Husband)

Hypothesis 4 – The MC will be perceived as having fewer barriers to participation than traditional therapy

As shown in Table 2, “Fewer Barriers” reasons for seeking an MC were offered by 14.1% of participants during the assessment interviews. These included statements that suggested the MC was perceived as being convenient, or did not seem as threatening or intimidating as traditional therapy.

Furthermore, when responding to the self-report survey about why they chose to participate in the MC rather than in traditional couple therapy (as shown in Table 4), 17.8% of the responses addressed fewer logistical barriers including expense and time. Additionally, fewer barriers was written-in as “Other” by 6.8% of treatment couples and 8.8% of the treatment and control couples combined.

Some couples explicitly noted fewer barriers as a reason for seeking an MC.

The main thing was it wasn’t a major time commitment…. I work nights, he works days, so scheduling things is kind of tricky. But this wasn’t too bad and it was spread over a good amount of time, and the questionnaires we could do from home, so that was a main factor. (Wife)

DISCUSSION

The need to develop interventions that can overcome existing barriers to couple treatment-seeking is an ongoing challenge to the newest generation of researchers. Data from the current study indicate that the MC can attract couples with mild to moderate relationship distress as well as those naïve to mental health treatment. In order for interventions to reach couples who may not know they are at risk, the service must appeal to those who perceive themselves as healthy. Because the MC attracted couples who self-identified as satisfied but typically had distressed GDS scores, as well as couples who often gave Veiled reasons for seeking treatment (although preliminary), it appears possible that the MC does cast this kind of broad net.

Additionally, the mismatch between high rates of marital distress and low rates of couple therapy utilization has left an urgent, unmet need. Although engaging the first-time mental health client is particularly difficult, over 63% of MC participants had never sought a couple-level intervention previously, and for over 32% the MC was their first foray into mental health services. Furthermore, although it was more often the female partners who initiated contact with the MC study, 47.8% of the participants were male. Given that research suggests that clients are more likely to re-use mental health services after the first time (Bringle & Byers, 1997), participating in the MC could increase future mental health utilization by men.

Fifty-three percent of MC participants had previously participated in individual therapy, the most common type of mental health treatment in our society today. However, while it has been shown that individual treatment can improve marital satisfaction as a result of improvements in personal levels of distress, research does not support individual therapy as the most effective way to address relationship issues (Atkins, Dimidjian, Bedics, & Christensen, 2009). Couples treatment has been shown to be more effective than individual treatment for many domains that can influence the relationship (Browne, 1995). Unfortunately, 49.7% of MC participants who had previously engaged in individual therapy had never participated in couple therapy, again highlighting the need for more attractive and accessible couple level interventions.

What mechanisms might enable the MC to attract couples who would not normally seek mental health services? Although further research is needed to examine the active mechanisms, an important component appears to be the marital health model. Emphasizing health and a checkup resonated with many couples, and this trend will perhaps continue to rise due to recent mental health parity legislation.

It looked like you were trying to establish a checkup yearly almost like going for a physical. I thought it was a good idea. (Wife)

But out of honesty, everyone’s relationship, especially one that’s lasted 22 years…there’s no harm that can come from a 22,000 mile check up. (Husband)

I’m a physician and I thought it was a neat concept similar to a physical or dental example…a psychological exam for couples. (Wife)

The marital health language of the MC also supports the idea of actively taking care of one’s marriage like other valued areas in life.

We’re both very proactive; we’re just good about our physical and mental health and I was like ‘this makes sense!’ (Wife)

I think it’s healthy that everybody gets a checkup…. Whether you want to call it preventative maintenance, it’s good to have a checkup to find out what’s going on if there are things going on. (Husband)

There are several potentially useful clinical implications of these findings. Couple therapists could utilize a brief checkup model to attract unreached couple populations in various communities. Efforts to facilitate dissemination of the checkup are currently underway. The checkup model could also be generalizable to other groups. For example, many parents could benefit from parenting services but do not seek them because they are not experiencing a severe problem (e.g. court mandate, conduct disordered child, etc.). We are currently exploring a potential “parenting checkup” which could provide a health frame to attract at-risk parents who would not ordinarily seek services.

Additionally, many areas within the mental health field are increasingly emphasizing the importance of motivation to successful treatment (e.g. Goldfried, 2011). Behavioral Couples Therapy researchers have found a lack of motivation to be the largest single barrier to treatment engagement for couples where one partner has a substance abuse disorder (O’Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2006). Adding a couple-level motivational component to a variety of interventions could increase treatment compliance by engaging and strengthening the marital system as support and encouragement.

Although these results are promising, several limitations should be noted. A primary concern regarding generalizability is that the current findings occurred in the context of a paid research study. A small percentage of participants (8–16%, depending on data collection method) indicated that one of their reasons for participation was the research payment. About 9% of the sample suggested that they chose the MC because of cost considerations. A similar proportion of the population might resist an MC in the community due to cost, but it should be noted that the MC would require considerably less time and money than would a full course of traditional therapy.

It is encouraging that the MC appears to attract a diverse group of couples in terms of marital functioning and previous treatment utilization. Mildly and moderately distressed couples have historically been overlooked and underserved by couple interventions, leaving many couples vulnerable to accumulating marital deterioration. However, the MC does unfortunately appear vulnerable to several familiar barriers to mental health services such as attracting a predominantly White, middle-class, educated population, and women initiating contact more often than men. Most health services, including medical and dental clinics, suffer similar imbalances in terms of participation, a significant problem that remains to be addressed. This reminds us again that simply opening the doors to mental health services is not enough to attract traditionally underserved populations, but rather that mental health providers must actively reach out to diverse communities. Relatedly, although the group of 12 randomized treatment couples who did not follow through with the in-person MC is too small to formulate more than tentative interpretations, indications that these couples were significantly older, less educated, and trending toward less household income could imply that couples who are more stressed may experience additional barriers to participation in the MC. One explanation may be that couples with lower socioeconomic status face greater logistical barriers to participating in even a short-term intervention.

Overall, these data suggest that the MC is a promising approach for encouraging a broad range of couples who might not otherwise seek services to actively attend to their marital health. Previous research indicated that participation in the MC also improves relationship outcomes across a range of marital health domains. If the ongoing study replicates previous results, the MC model may have the potential to significantly diminish the occurrence of marital ill-health for a larger number of couples.

References

- Anker MG, Duncan BL, Sparks JA. Using client feedback to improve couple therapy outcomes: A randomized clinical trial in a naturalistic setting. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):693–704. doi: 10.1037/a0016062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Dimidjian S, Bedics JD, Christensen A. Couple discord and depression in couples during couple therapy and in depressed individuals during depression treatment. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(6):1089–1099. doi: 10.1037/a0017119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R, Hannah MT. Preventive Approaches in Couples Therapy. PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bringle RG, Byers D. Intentions to seek marriage counseling. Family Relations. 1997;46:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Browne K. Alleviating spouse relationship difficulties. Counseling Psychology Quarterly. 1995;8(2):109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Jacobson NS, Babcock JC. Integrative behavioral couple therapy. In: Jacobson N, Gurman A, editors. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti Domenic V. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova JV. The Marriage Checkup: A Scientific Program for Sustaining and Strengthening Marital Health. New York: Jason Aronson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova JV, Scott RL, Dorian M, Mirgain S, Yaeger D, Groot A. The marriage checkup: A motivational interviewing approach to the promotion of marital health with couples at-risk for relationship deterioration. Behavior Therapy. 2005:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova JV, Warren LZ, Gee CB. Motivational interviewing as an intervention for at-risk couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2001;27(3):315–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2001.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Atkins DC, Christensen A. Who’s dragging their feet? Husbands and wives seeking marital therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29(2):165–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Marital therapy, retreats and books : The who, what, when and why of relationship help seeking. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2009;35(1):18–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Simpson LE, Christensen A. Why do couples seek marital therapy? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(6):608–614. [Google Scholar]

- Gee CB, Scott RL, Castellani AM, Córdova JV. Predicting 2- Year marital satisfaction from partners’ reaction to a marriage checkup. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2002;28:399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2002.tb00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfried MR. Generating research questions from clinical experience: Therapists’ experiences in using CBT for Panic Disorder. The Behavior Therapist. 2011;34(4):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Christensen A. Acceptance and change in couple therapy. New York: Norton; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, Stanley SM, Glenn ND, Amato PR, Nock SL, Markman HJ, et al. Marriage in Oklahoma: 2001 baseline statewide survey on marriage and divorce (S02096 OKDHS) Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Department of Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Knudson-Martin C, Mahoney AR. Couples, gender, and power: Creating change in intimate relationships. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morrill MI, Córdova JV. Building Intimacy Bridges: From the Marriage Checkup to Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy. In: Gurman A, editor. Clinical Casebook of Couple Therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 331–354. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Divorce Rate in the U.S., 2008. Family Profiles, FP-09-02. 2009 http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file78753.pdf.

- O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W. Behavioral Couples Therapy for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JQ, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self- change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JM, Fitzgerald LF. Overcoming the masculine mystique: Preferences for alternative forms of assistance among men who avoid counseling. Journal of Counseling. 1992;39:240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Russell L. Mental health care services in primary care: Tackling the issues in the context of health care reform. Center for American Progress; 2010. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Baldwin SA. Meta-analysis of MFT interventions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29:547–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DK. Marital Satisfaction Inventory, Revised (MSI-R): Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Hecht J, Miller IW. The Family Check-Up: A pilot study of a brief intervention to improve family functioning in adults. Family Process. 2006;45(2):223–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott IH. Seeking help for marital problems before separation. Australian Journal of Sex, Marriage & Family. 1986;7(3):154–164. [Google Scholar]