Self-perpetuating protein conformers (prions) have been described in animals (including human) and fungi (including yeast), and linked to both diseases and heritable traits (1–4). One would wonder if plants have them too. Indeed, a paper by Chakrabortee et al. (5), from the laboratory of Susan Lindquist, provides a first example of a plant protein behaving as a prion, at least in the heterologous (yeast) system. Chakrabortee et al. checked several domains of Arabidopsis thaliana proteins with potential prion properties, predicted by a computational search, and confirm that one of them, from the protein named Luminidependens (LD), can acquire and propagate a prion state in yeast cells when substituted for the prion domain of yeast prion protein Sup35.

Notably, the LD protein is involved in the “vernalization” phenomenon, an example of epigenetic “memory” of previous environmental changes (6). The term “vernalization,” known for about a century (7), refers to triggering the flowering and reproduction process after the exposure to cold weather. Ironically, Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko and his followers referred to vernalization in their fight against Mendelian genetics, arguing that this phenomenon confirms heritability of acquired traits (8). Lysenko had started his scientific career by applying the vernalization procedure to increase productivity of Soviet crops (9). Following initial success, Lysenko and his colleagues rejected the chromosome theory of inheritance and postulated that a variety of cellular components may serve as carriers of heritable patterns. This attack, transformed from scientific discussion to the administrative (and sometimes criminal) persecution of opponents, eventually led to complete destruction of research and teaching in Mendelian genetics in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) by the end of 1940s (8). No wonder that after restoration of Mendelian genetics in the USSR in the 1960s, Lysenko’s name had become synonymous with scientific illiteracy for upcoming generations of Russian biologists. However, it is worth remembering that the great Soviet biologist Nikolay Vavilov, who himself eventually fell victim to Lysenkoist persecutions, initially praised Lysenko’s work on vernalization (8, 10), suggesting that it might possess a certain scientific value.

Modern studies of yeast and fungal prions confirm that protein conformations (that is, alterations of cellular components that are distinct from the DNA-based chromosomal genes) can control certain heritable traits (4). Sadly, instead of becoming early pioneers of nonconventional mechanisms of inheritance, Lysenko and his followers chose to spread their views by administrative means, eventually losing the scientific contents of these views in the process. Likely this has even delayed studies of protein-based inheritance systems per se (especially in plants), as the rest of the academic community a priori placed them into the same garbage basket with others (sometimes indeed illiterate) of Lysenko’s “innovations.” This example shows that even potentially productive scientific ideas and results may bring harm if their protagonists stick to nonscientific means for achieving dominance in the field.

According to Chakrabortee et al., the prion domain of LD protein does confer properties of a heritable protein-based element to the reporter yeast protein to which it is fused (5). Similar to endogenous yeast prions (4, 11), transient overproduction of the LD prion domain generates oligomers (5) that can reproduce themselves by immobilizing (and possibly conformationally altering) the monomeric (substrate) protein of the same sequence after overproduction is turned over. Because protein levels may vary depending on physiological conditions, such a prion induction by transient protein overproduction may reflect physiological regulation of prion formation.

However, in contrast to the majority of known endogenous yeast prions (4, 12), the LD-based prion (termed [LD+]) apparently does not require the disaggregating chaperone Hsp104 for its propagation, and therefore is not affected by perturbations of Hsp104 levels and activity (5). Hsp104, working together with Hsp70 and Hsp40 partners, is needed for fragmenting prion polymers into the oligomeric seeds, thus initiating new rounds of prion propagation and transmission (for review, see ref. 4). Lack of Hsp104 involvement in the propagation of [LD+] is especially striking because plants possess an Hsp104 ortholog (13). On the other hand, at least two yeast Hsp104-independent prions, [GAR+] (14) and [ISP+] (15), have been reported. Notably, [LD+] produces smaller oligomers in vivo, compared with most endogenous yeast prions (5). Small oligomer size may explain lack of the Hsp104 requirement. Moreover, Chakrabortee et al. (5) show that the propagation of [LD+] is influenced by other yeast chaperones, specifically Hsp70 (the Ssa subfamily) and Hsp90. It appears likely that different (although possibly overlapping) chaperone machineries are operating on different types of prion oligomers.

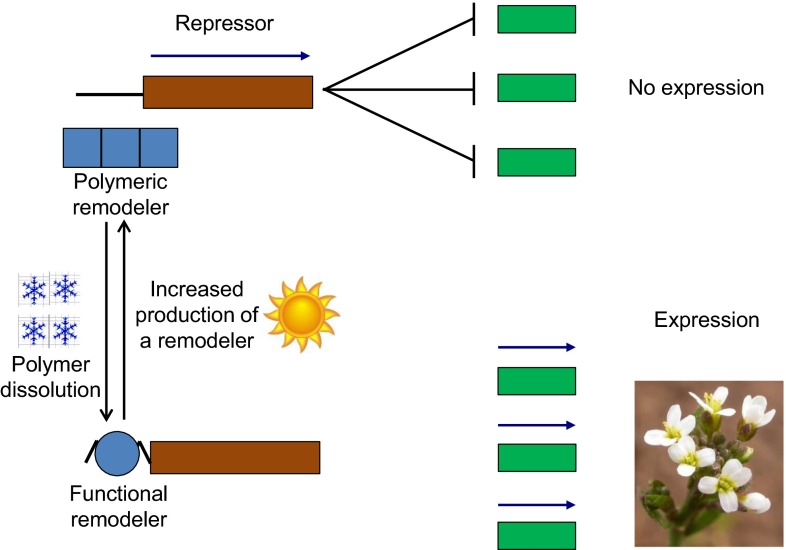

The LD protein possesses features of the transcriptional regulator (possibly, a chromatin remodeler) (16), which may explain its involvement in the vernalization pathway. Indeed, vernalization leads to heritable (in the course of cell generations) modifications of chromatin and gene expression (6). However, molecular processes leading to these changes and capable of “recording” the effect of cold treatment in the form of molecular “memory” remain unclear. Prions are built as perfect machines of molecular memory, because self-perpetuating abilities enable them to record and reproduce the memory of acquired alteration that initially caused prion formation. As such, prion-like elements may play a role of universal triggers connecting environmental signals to cellular and organismal processes. It is possible that at least some epigenetic pathways use a two-level regulatory mechanism, with a prion-like domain in the regulatory protein initially sensing and recording a signal, followed by a regulatory change in the chromatin organization or in the mode of gene transcription. For example, if a prion-forming remodeler exists in the polymeric (inactive) form during the unfavorable conditions (such as cold weather), converts to the nonprion (active) form once such conditions pass, and then generates a prion-like state again as a result of increased expression during favorable conditions, this may explain induction of the flowering pathway after cold weather and return to the repressed conditions after the flowering period is over (Fig. 1). Alternatively, it is possible that the polymeric form is active and is induced by cold treatment (not shown). The impact of environmental conditions on prion formation and propagation has been reported for various yeast prions (for review, see ref. 4), although much remains to be understood in regard to the molecular basis of these effects.

Fig. 1.

A hypothetical model for the regulation of gene expression by a prion-like chromatin remodeler. In the case of Arabidopsis, “remodeler” would refer to the LD protein, and potentially to other regulators with similar properties, and “repressor” would refer to the Flowering Locus C protein. The sun image indicates warm weather; the snowflakes indicate cold. An alternative model would suggest that the polymeric (prion) form is induced by cold and is active in chromatin repression.

Previously, prion-like properties of the posttranscriptional regulatory protein, CPEB, have been linked to long-term neuron potentiation in animal systems (for review, see ref. 17). Moreover, many yeast proteins with potential prion domains are transcriptional regulators or chromatin remodelers, and some of them are proven to form a prion in their native state (4, 18, 19). Prion-like behavior of [LD+] suggests that such a mechanism might be extended to plants. It now becomes an intriguing possibility that prion-like switches in chromatin remodelers may play a role in epigenetic regulation in animals and humans.

Obviously, the yeast prion propagation assay used by Chakrabortee et al. (5) is not without its limitations. It remains to be seen if LD can generate and maintain a prion state in its native

A paper by Chakrabortee et al., from the laboratory of Susan Lindquist, provides a first example of a plant protein behaving as a prion, at least in the heterologous (yeast) system.

(plant) system. In addition, the authors were not able to prove prion properties of three other vernalization-related Arabidopsis proteins in yeast, despite the fact that these proteins contain prion-like domains exhibiting certain aggregation patterns (5). One possible explanation of this failure could be that the propagation of some plant-based prions is impaired in the heterologous chaperone environment of yeast cytoplasm. Assays based on initial prion nucleation rather than on the propagation of prion state could be more sensitive for screening prion candidates from other organisms in yeast.

Still, discovery of the first plant protein with proven in vivo prion properties opens new horizons for studying epigenetic phenomena in plants. By their nature, plants are made for prions, because they possess cytoplasmic bridges between cells and are frequently capable of vegetative proliferation. Thus, prion-like proteins produced in certain cells can potentially spread to other cells, so that prions may transmit a signal from the receptor tissue to the tissue developing a response. Moreover, prions could be transmitted even to vegetative progeny, generating new regulatory states heritable at the organismal level. Such events may explain physiological properties of interspecies grafts (a so-called “vegetative hybridization” broadly employed by Ivan Michurin and also used by Lysenkoists against Mendelian genetics) (8, 10). Even the “pangenesis” concept of Charles Darwin, postulating the existence of “gemmulas”—particles produced by different cells and tissues to carry heritable traits to the next generation (20)—may get a new molecular foundation.

Novel ideas frequently recapitulate something that has been previously proposed and forgotten. It is gratifying to believe that “seeds” can survive through difficult times, be reproduced in a prion-like fashion, and eventually reemerge over a threshold of skepticism. This is an encouragement for scientists whose thoughts were not immediately accepted by the academic community. Of course, such seeds require a tremendous amount of convertible “substrate” to be produced by experimental efforts in order for them to proliferate.

Acknowledgments

Y.O.C. is supported by Grants MCB 1516872 from the NSF and 14-50-00069 from the RSF.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 6065 in issue 21 of volume 113.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216(4542):136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colby DW, Prusiner SB. Prions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(1):a006833. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wickner RB. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: Evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264(5158):566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chernova TA, Wilkinson KD, Chernoff YO. Physiological and environmental control of yeast prions. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38(2):326–344. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakrabortee S, et al. Luminidependens (LD) is an Arabidopsis protein with prion behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(21):6065–6070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604478113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song J, Irwin J, Dean C. Remembering the prolonged cold of winter. Curr Biol. 2013;23(17):R807–R811. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasner G. Beiträge zur physiologischen Charakteristik sommer- und winterannueller Gewächse, insbesondere der Getreidepflanzen. Zeit Bot. 1918;10:417–480. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soyfer VN. Lysenko and the Tragedy of Soviet Science. Rutgers Univ Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lysenko TD. 1928. Vliianie termicheskogo faktora na prodolzhitel’nost’ faz razvitiia rastenii. Opyt so zlakami i khlopchatnikom [Effect of the thermal factor on the duration of the developmental phases of plants. Experiments with cereals and cotton.] Trudy Azerbaidzh Tsentr Op Sta (Baku) 3. (Russian)

- 10.Roll-Hansen N. A new perspective on Lysenko? Ann Sci. 1985;42(3):261–278. doi: 10.1080/00033798500200201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chernoff YO, Derkach IL, Inge-Vechtomov SG. Multicopy SUP35 gene induces de-novo appearance of psi-like factors in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1993;24(3):268–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00351802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [psi+] Science. 1995;268(5212):880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schirmer EC, Lindquist S, Vierling E. An Arabidopsis heat shock protein complements a thermotolerance defect in yeast. Plant Cell. 1994;6(12):1899–1909. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown JC, Lindquist S. A heritable switch in carbon source utilization driven by an unusual yeast prion. Genes Dev. 2009;23(19):2320–2332. doi: 10.1101/gad.1839109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogoza T, et al. Non-Mendelian determinant [ISP+] in yeast is a nuclear-residing prion form of the global transcriptional regulator Sfp1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(23):10573–10577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005949107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee I, et al. Isolation of LUMINIDEPENDENS: A gene involved in the control of flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1994;6(1):75–83. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Si K, Kandel ER. The role of functional prion-like proteins in the persistence of memory. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(4):a021774. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du Z, Park KW, Yu H, Fan Q, Li L. Newly identified prion linked to the chromatin-remodeling factor Swi1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Genet. 2008;40(4):460–465. doi: 10.1038/ng.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 2009;137(1):146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darwin CR. The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. Abrahams Magazine Service; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]