There is no substitute for dramatic reductions in the emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases to mitigate the negative consequences of climate change and, concurrently, to reduce ocean acidification. Mitigation, although technologically feasible, has been difficult to achieve for political, economic, and social reasons that may persist well into the future.

National Research Council (1)

Climate change is a global problem with grave implications: environmental, social, economic, political and for the distribution of goods. It represents one of the principal challenges facing humanity in our day. … There is an urgent need to develop policies so that, in the next few years, the emission of carbon dioxide and other highly polluting gases can be drastically reduced, for example, substituting for fossil fuels and developing sources of renewable energy.

Pope Francis (2)

Our planet is sustained by a web of interconnected and interdependent cycles (Fig. 1). Methane, an important component of the global carbon cycle, is widely used as a fuel by humans and as a carbon and energy source by microbes. Although invisible to our eyes, methane casts a dark specter through its proficiency to trap infrared radiation from the sun. As greenhouse gases, methane and carbon dioxide are recognized to be the most potent contributors to global warming. Increases in the atmospheric levels of these gases have been linked to the melting of glaciers, rising sea levels, increasing global temperatures, and other dire effects associated with climate change. Strategies to respond to climate change include: mitigation by reducing emissions or sequestering these gases from the atmosphere; climate intervention (albedo modification, CO2 removal); or adaptation to the impending environmental, ecological, social, political, and economic destabilization (1). Duin et al. (3), in an intriguing recent PNAS article, describe a strategy to mitigate rising methane levels by inhibiting the enzyme that catalyzes the biosynthesis of nearly all of the methane found on earth.

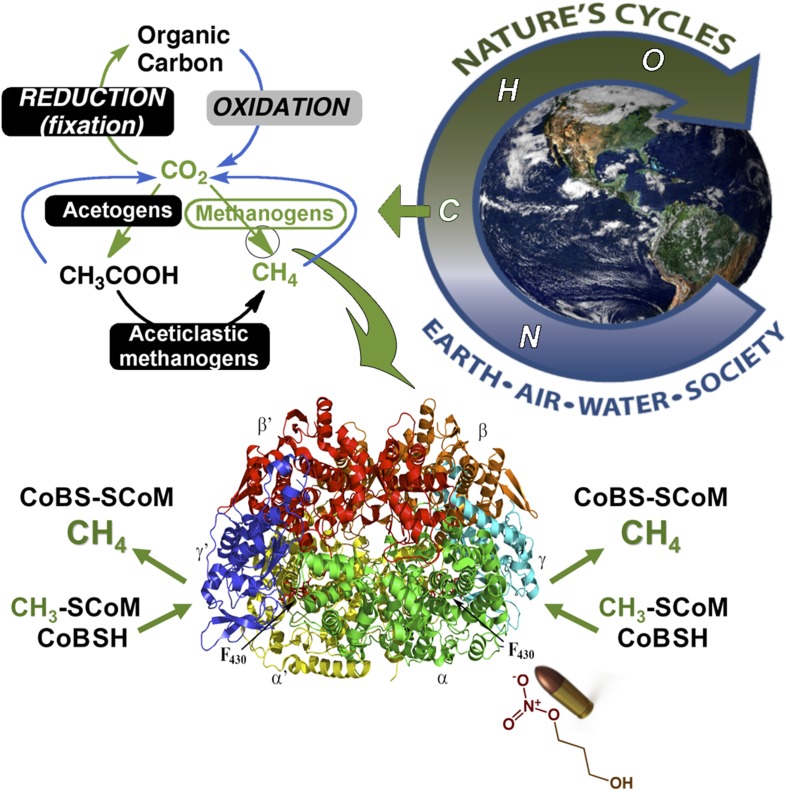

Fig. 1.

Our planet is sustained by the web of interconnected and interdependent nitrogen, carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen cycles. The carbon cycle involves the transformation of carbon dioxide into organic compounds by photosynthesis and other reductive processes (green) and its return to the atmosphere (blue) through respiration and various oxidative reactions. Anaerobic microbes like acetogens and methanogens are masters of carbon dioxide activation and reduction. In the final and rate-limiting step of methanogenesis, MCR reduces methyl-SCoM to methane. This enzyme provides a rich fuel for man and microbe. However, the oversupply of methane to the atmosphere contributes to climate change. As recently reported in PNAS (3), targeting MCR with a NOP bullet leads to MCR inactivation, which halts methanogenesis in pure cultures and in the mixed microbial community of the rumen.

The enzyme is methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR), which catalyzes the conversion of a methyl-thioether (methyl-coenzyme M, methyl-CoM) in the presence of a second thiol cofactor (coenzyme B, CoB) to methane and the disulfide (CoMS-SCoB) (Fig. 1). The heart of MCR is a nickel cofactor, called cofactor F430, that is only active in the Ni(I) state, a state that is highly vulnerable to oxidative inactivation. MCR and F430 are found only in methanogens, strictly anaerobic microbes found in most oxygen-depleted environments, including the human gut and the rumen of mammals like cattle, sheep, and camels. Ruminants are responsible for eructating up to 20% of worldwide methane emissions. Besides adding to the greenhouse gas global warming potential, the energetic cost of methane lost to the atmosphere decreases feed efficiency. Duin et al. (3) ask two questions: (i) Is there a magic bullet that can specifically inactivate MCR and, (ii) if so, can it target the MCR active site to arrest growth and methane production by these microbes?

The overall strategy is standard; for example, our pharmaceutical industry is largely based on chemicals that target metabolic enzymes. Similarly, in the agricultural arena, an antibacterial compound (monensin) that decreases methanogenesis (4) is fed to nearly all feedlot cattle in the United States. This antibiotic increases the production of beneficial fatty acids, like propionate (4–6), which are metabolized by the animal. However, monensin is relatively nonspecific and impairs beneficial processes, like acetic acid formation by acetogenic bacteria (7, 8). Other antimethanogenesis compounds that have been developed include 2,4-bis (trichloromethyl)benzo[1,3] dioxins (9), an inhibitor of methanopterin biosynthesis (10), and nitrogen oxides (nitrate, nitrite, NO, and N2O) (11–14). Whereas the former two compounds have complex structures, the third is simple. Duin et al. (3) generated another simple inhibitor: 3-nitrooxypropanol (NOP), a CoM substrate analog containing a nitrogen oxide attached to a three-carbon alcohol.

The answer to the first question asked above is “yes.” Exposure of MCR for only a few minutes at low micromolar levels of NOP led to complete inactivation. Spectroscopic and X-ray crystallographic experiments demonstrated that the compound specifically targets the MCR active site. The second answer is a qualified “yes.” The bullet does abruptly and specifically halt methane production and growth; however, over time the methanogen can revive this all-important enzyme, restoring growth and methane production. Furthermore, rumen microbes are able to metabolize NOP. Another potential limitation is that it requires 100-fold higher levels of NOP to inhibit growth and methane formation in some methanogens than in others.

Now more questions arise: Can and should this strategy be tested as a food supplement in live animals to mitigate methane emissions? How much does the transient and uneven nature of this inhibition limit the use of NOP? Can the resilient rumen flora mount an effective response and become resistant to NOP? Further research is warranted to determine if this is a promising strategy as part of a multifaceted approach to address the crisis of an increasingly warming earth. Furthermore, it will be interesting to determine how complete inhibition of methanogenesis in the rumen affects animal health and feed efficiency.

Acknowledgments

Research on methanogenesis in S.W.R.’s laboratory is funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-FG02-08ER15931. Research on methane oxidation is funded by the US Department of Energy, Advanced Research Project Agency–Energy, under Award DE-AR0000426.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 6172.

References

- 1.Committee on Geoengineering Climate: Technical Evaluation and Discussion of Impacts; Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate; Ocean Studies Board; Division on Earth and Life Studies; National Research Council . Climate Intervention: Carbon Dioxide Removla and Reliable Sequenstration. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pope Francis (2015) Laudato Si. Encyclical letter On Care for Our Common Home. Available at w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html. Accessed April 27, 2016.

- 3.Duin EC, et al. Mode of action uncovered for the specific reduction of methane emissions from ruminants by the small molecule 3-nitrooxypropanol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. May 2, 2016;113:6172–6177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600298113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornton JH, Owens FN. Monensin supplementation and in vivo methane production by steers. J Anim Sci. 1981;52(3):628–634. doi: 10.2527/jas1981.523628x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuffey RK, Richardson LF, Wilkinson JID. Ionophores for dairy cattle: Current status and future outlook. J Dairy Sci. 2001;84(E suppl):E194–E203. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armentano LE, Young JW. Production and metabolism of volatile fatty acids, glucose and CO2 in steers and the effects of monensin on volatile fatty acid kinetics. J Nutr. 1983;113(6):1265–1277. doi: 10.1093/jn/113.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drake HL, editor. 1994. Acetogenesis (Chapman and Hall, New York), pp 647.

- 8.Ragsdale SW, Pierce E. Acetogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 fixation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784(12):1873–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies A, Nwaonu HN, Stanier G, Boyle FT. Properties of a novel series of inhibitors of rumen methanogenesis; in vitro and in vivo experiments including growth trials on 2,4-bis (trichloromethyl)-benzo [1, 3]dioxin-6-carboxylic acid. Br J Nutr. 1982;47(3):565–576. doi: 10.1079/bjn19820068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumitru R, et al. Targeting methanopterin biosynthesis to inhibit methanogenesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(12):7236–7241. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7236-7241.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kluber HD, Conrad R. Effects of nitrate, nitrite, NO and N2O on methanogenesis and other redox processes in anoxic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25(3):301–318. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Z, Yu Z, Meng Q. Effects of nitrate on methane production, fermentation, and microbial populations in in vitro ruminal cultures. Bioresour Technol. 2012;103(1):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Z, Meng Q, Yu Z. Effects of methanogenic inhibitors on methane production and abundances of methanogens and cellulolytic bacteria in in vitro ruminal cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(8):2634–2639. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02779-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulshof RB, et al. Dietary nitrate supplementation reduces methane emission in beef cattle fed sugarcane-based diets. J Anim Sci. 2012;90(7):2317–2323. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]