Significance

Following egress from the endocytic compartment, nonenveloped DNA viruses have a distinct cytoplasmic phase whereupon the viral genome is transported into the nucleus of infected cells via nuclear pores. In contrast, the human papillomavirus (HPV) waits for nuclear envelope breakdown during mitosis to gain access to the nucleus. Here we provide evidence that the HPV genome resides continuously in a transport vesicle until mitosis is completed. This suggests that membrane-bound vesicles can temporally exist in the nucleus. Because vesicles are not normally detected in the nucleus, this also points to the existence of an unrecognized cell pathway for the disposal of nuclear vesicles.

Keywords: HPV entry, vesicular transport, mitosis, digitonin, nuclear vesicle

Abstract

During the entry process, the human papillomavirus (HPV) capsid is trafficked to the trans-Golgi network (TGN), whereupon it enters the nucleus during mitosis. We previously demonstrated that the minor capsid protein L2 assumes a transmembranous conformation in the TGN. Here we provide evidence that the incoming viral genome dissociates from the TGN and associates with microtubules after the onset of mitosis. Deposition onto mitotic chromosomes is L2-mediated. Using differential staining of an incoming viral genome by small molecular dyes in selectively permeabilized cells, nuclease protection, and flotation assays, we found that HPV resides in a membrane-bound vesicle until mitosis is completed and the nuclear envelope has reformed. As a result, expression of the incoming viral genome is delayed. Taken together, these data provide evidence that HPV has evolved a unique strategy for delivering the viral genome to the nucleus of dividing cells. Furthermore, it is unlikely that nuclear vesicles are unique to HPV, and thus we may have uncovered a hitherto unrecognized cellular pathway that may be of interest for future cell biological studies.

A major hurdle of DNA viruses during a primary infection is successful navigation of the cytoplasm to deliver the viral genome to the nucleus. Foreign DNA that enters the cytoplasm is susceptible to being sensed by innate immune sensors (1). Not surprisingly, viruses have evolved mechanisms to evade detection by these sensors. For example, herpesviruses and adenoviruses both egress into the cytoplasm, yet protect their viral DNA by keeping it encased in viral capsids until directly transferring it into the nucleus through the nuclear pore complex. In contrast, the capsid is unlikely to protect papillomavirus (PV) genomes while traversing the cytoplasm, because the major capsid protein is lost in the endocytic compartment (2).

The PV capsid is composed of two viral proteins, the major capsid protein L1 and the minor capsid protein L2, which enclose a chromatinized, circular, double-stranded DNA genome ∼8 kb in size (3–6). Following primary attachment and internalization, acidification of early endosomes triggers capsid disassembly (7–22). Host cell cyclophilins release the majority of L1 from the L2 protein, which remains in complex with the viral genome (2, 23, 24). A large portion of the L2 protein translocates across the endocytic membrane to engage factors, including the retromer complex, dynein, sorting nexins, and rab GTPases, that mediate transport to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (25–33). An siRNA screen has suggested that nuclear pore complexes are not required for nuclear entry, but that nuclear envelope breakdown during mitosis is necessary (34, 35).

Currently, when and how the human PV (HPV) genome egresses from the membranous compartment is unclear. Here we present evidence indicating that after the onset of mitosis, the viral genome of HPV type 16 (HPV16), an HPV type associated with malignancies (36), egresses from the TGN and associates with microtubules. The viral genome migrates along microtubules to the condensed chromosomes, facilitated by the L2 protein. During this time, the viral genome resides in a vesicular compartment, presumably a transport vesicle, until the completion of mitosis, delaying viral gene expression.

Results

Incoming Viral Genome Is Trafficked in Membrane-Bound Vesicles During Mitosis.

To study the trafficking of HPV virions, we used efficient generation of pseudoviral particles, which are considered indistinguishable from native virions but encapsidate a reporter plasmid (pseudogenome) (4, 37, 38). We also generated quasivirions in 293TT cells that encapsidate the HPV16 genome (39). For most experiments, we used particles containing a pseudogenome labeled with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU), a nucleotide analog that can be detected by immunofluorescent staining using Click-iT chemistry (40). Using differential permeabilization and epitope-mapped monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 1A), we recently demonstrated that the L2 protein assumes a transmembranous configuration in the TGN where the putative transmembrane domain (TM; residues 45–65) separates the luminal epitope (residues 18–35) from epitopes located C-terminally of the TM domain and facing the cytosol (32). In contrast, L1 protein was found exclusively in the luminal compartment of the TGN.

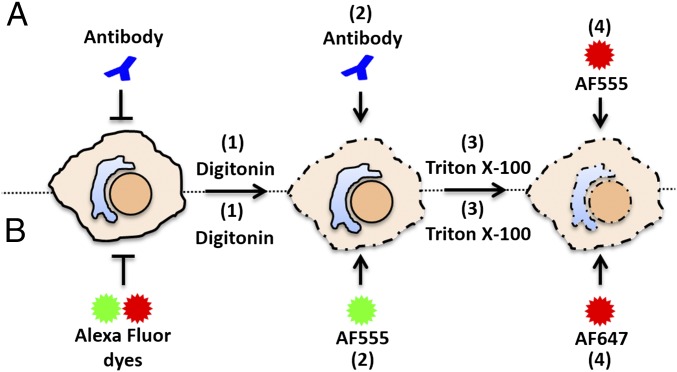

Fig. 1.

Diagram of differential staining assay for antibodies or Alexa Fluor dyes. (A) (1) Cells infected with EdU-labeled pseudovirus are fixed and permeabilized with DIG or TX-100, (2) incubated with primary and secondary antibodies and fixed briefly again, (3) permeabilized with TX-100, and (4) treated with AF555 (red) in Click-iT reaction buffer. (B) (1) Infected cells are fixed, permeabilized with DIG or TX-100, (2) treated with AF555 (green) in Click-iT reaction buffer, (3) permeabilized with TX-100, and (4) treated with AF647 (red) in Click-iT reaction buffer.

Because the point at which the viral genome egresses from membranous compartments during infectious entry remains unknown, we used the same approach to test for epitope accessibility in mitotic cells using EdU-labeled particles. HaCaT cells were infected with HPV16 pseudovirus for 24 h and then selectively permeabilized using a low concentration of digitonin (DIG) that permeabilizes the plasma membrane and early endosomes but not TGN, Golgi, or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (32). We observed that the epitope comprising residues 18–35 as well as L1 was still inaccessible in cells undergoing mitosis, whereas a downstream epitope (residues 163–170) was accessible (Fig. 2A), suggesting that L2 protein is still transmembranous during mitosis.

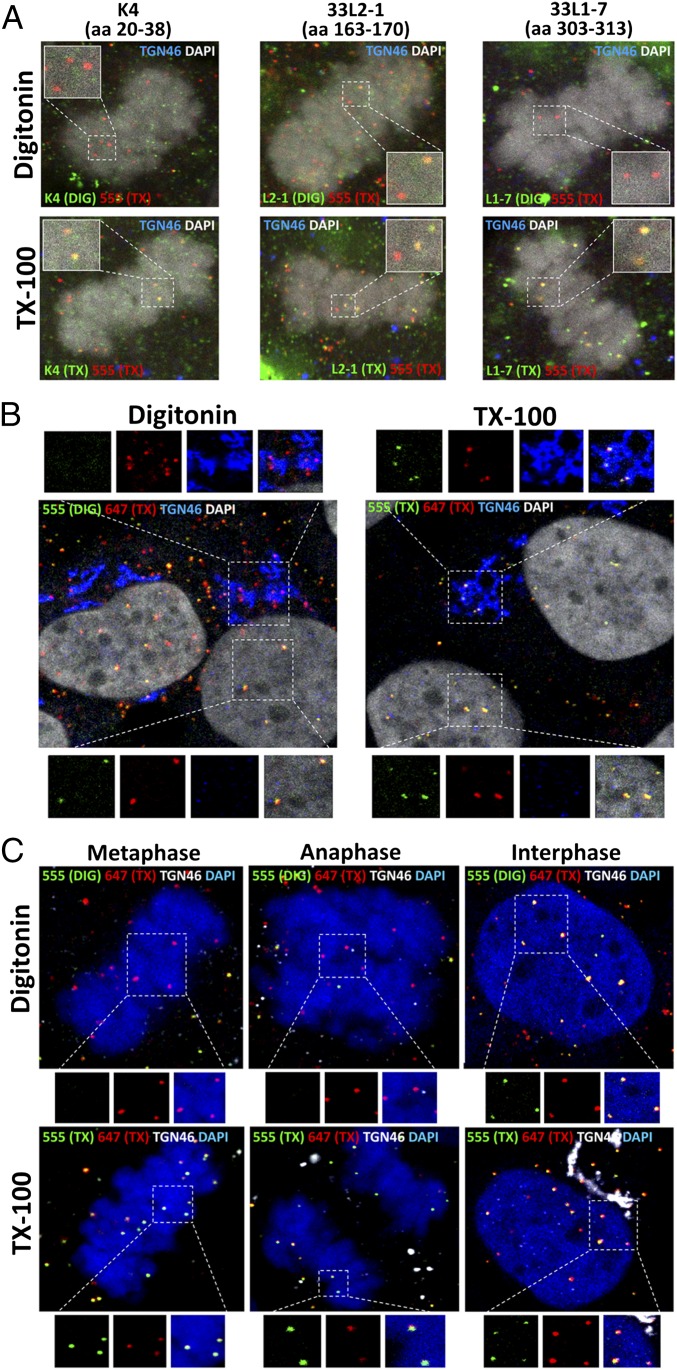

Fig. 2.

Incoming viral genome resides in a vesicle until the completion of mitosis. (A) At 24 hpi with EdU-labeled pseudovirus, HaCaT cells were fixed, permeabilized with 5 µg/mL of DIG or 0.5% TX-100, and incubated with primary L2-specific antibodies K4 (amino acids 20–38), 33L2-1 (amino acids 163–170), or L1-specific antibody 33L1-7 (amino acids 303–313), followed by a subsequent secondary antibody (green). Cells were fixed again, permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF555 (red) in Click-iT reaction buffer. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (white). A luminal epitope of TGN46 (blue) served as a control to assess intracellular membrane integrity. Note the lack of reactivity of both the K4 and 33L1-7 antibodies in DIG-treated cells. (B) HaCaT cells were infected as described above. At 24 hpi, cells were fixed, permeabilized in 0.625 µg/mL DIG or 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF555 (green) in Click-iT reaction buffer. Cells were fixed again, permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF647 (red). TGN46 (blue) was stained after TX-100 treatment. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (white). (C) HaCaT cells were infected and differentially stained as described in B. A luminal epitope of TGN46 (white) served as a control to assess intracellular membrane integrity. Note the absence of AF555 staining in pseudogenomes localized to the TGN and associated with mitotic chromosomes.

As reported previously, the L2-specific antibodies show a high level of background even in uninfected cells, along with a low signal intensity (32). In addition, the antibodies are large macromolecules of ∼150 kDa and have limited accessibility for proteins present in larger complexes. To achieve a higher level of sensitivity and better penetration, we developed an assay using the low-molecular-weight dyes Alexa Fluor (AF) 555 and AF647 (∼ 500 Da), which are not cell-permeable on their own but can readily penetrate cells after DIG treatment, as well as nuclei of DIG-permeabilized cells, through the nuclear pores (Fig. S1C).

Fig. S1.

Differential staining controls. (A) At 1 hpi, HaCaT cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.625 µg/mL DIG or 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF555 (green) in Click-iT reaction buffer. Cells were briefly fixed again, permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF647 (red) in Click-iT reaction buffer. The ECM marker Laminin 332 (LN332) (blue) was stained after TX-100 treatment. The nuclei are stained with DAPI (white). Note that the EdU puncta localized on the ECM is accessible to AF555 after DIG treatment. (B) HaCaT cells were infected with EdU-labeled HPV16 pseudovirus for 18 h in the presence of 1 µM BafA1. Differential staining of pseudogenomes was performed as described in A. A luminal epitope of TGN46 (white) served as a control to assess intracellular membrane integrity. (C) Uninfected HaCaT cells were pulse-labeled with 10 µM EdU for 4 h, then differentially stained as described in A. A luminal epitope of TGN46 (white) served as a control to assess intracellular membrane integrity. Note that host chromatin was accessible to AF555 after DIG treatment in interphase and all phases of mitosis. (D) HaCaT cells were infected with VACV for 1 h at 4 °C to allow binding. Cells were either directly fixed or shifted to 37 °C for 2 h and then fixed. Differential staining of VACV genomes was performed as described in A. A luminal epitope of TGN46 (white) served as a control to assess intracellular membrane integrity. (E) Quantification of dye accessibility to the VACV genome at 1 h after binding or 2 h after entry. Quantification is based on the number of double-positive EdU puncta as a percentage of total EdU puncta per image (n = 15 images). All P values are < 0.0005. Note that VACV genome localized at the cell surface was inaccessible to AF555, but became accessible after internalization in DIG-treated cells.

HaCaT cells were infected with HPV16 pseudovirus harboring an EdU-labeled pseudogenome. At 24 h postinfection (hpi), the cells were fixed, and the plasma membrane was selectively permeabilized using a low concentration of DIG. In a first Click-iT reaction, accessible DNA was stained with AF555. Then the cells were completely permeabilized with Triton X-100 (TX-100) and treated with AF647 in a second Click-iT reaction (Fig. 1B). We observed that the pseudogenome localized within the TGN during interphase was inaccessible to the AF555 dye after DIG treatment (Fig. 2B). In line with our results presented above, we observed that the pseudogenomes associated with condensed chromosomes at various stages of mitosis were also inaccessible to AF555 after DIG treatment (Fig. 2C). Only after the completion of mitosis did we observe double-positive staining from both dyes within the nucleus.

We performed several control experiments to demonstrate the usefulness of this approach. First, we observed double-positive staining of pseudogenomes present on the extracellular matrix, supporting the feasibility of sequential staining and the capability of the dyes to penetrate viral capsids (Fig. S1A). We then tested sequential staining of internalized virions in cells treated with bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) at 18 hpi. BafA1 prevents the trafficking and acidification of early endosomes, as well as the uncoating of HPV16 (Fig. S1B) (41, 42). In addition, we observed double-positive staining of cells that had been pulse-labeled with EdU during interphase and all stages of mitosis, suggesting that the plasma membrane can be permeabilized at all stages of the cell cycle under these conditions (Fig. S1C). Double-positive staining was also observed when DIG was replaced by TX-100 (Fig. S1 B and C).

We also tested our differential staining assay for enveloped vaccinia virus (VACV), which has a strict cytoplasmic phase during the infection (43). We observed that the EdU-labeled VACV DNA was inaccessible to AF555 on the cell surface and accessible to both dyes after internalization (Fig. S1 D and E). Taken together, these data suggest that the incoming HPV genome is inaccessible to small-molecule dyes throughout mitosis, and thus likely resides in a membranous compartment, possibly a transport vesicle.

Incoming Viral Genome Is Protected from Nuclease Digestion During Mitosis.

To support the foregoing findings, we performed biochemical analyses on cells arrested in mitosis. We used the cell-permeable Eg5 inhibitor III (Eg5i) to block Eg5 kinesin, a motor protein required for spindle bipolarity. Inhibition by Eg5i arrests the cells in a monoastral phenotype (44). Although the HPV entry process is highly asynchronous, we observed that the majority of EdU puncta localized at condensed chromosomes in cells infected with pseudovirions in the presence of Eg5i. When we coupled Eg5i treatment with our differential staining assay, we found that the pseudogenomes were inaccessible to AF555 after DIG treatment, confirming their residence in a membrane-bound compartment (Fig. 3A).

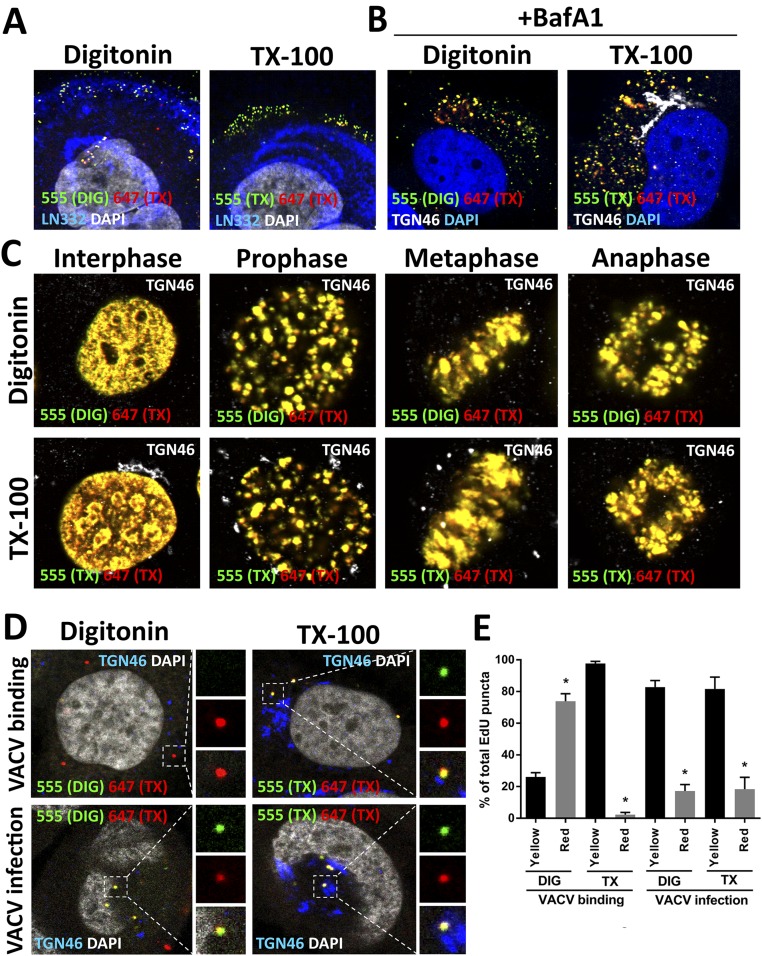

Fig. 3.

Vesicle protects the incoming viral genome from digestion during mitosis. (A) HaCaT cells were infected in the presence of Eg5i and differentially stained as described in Fig. 2 B and C. Note the absence of AF555 staining in pseudogenomes associated with arrested cells. (B) HaCaT and HeLa cells were infected with HPV16 pseudovirus for 24 h and 18 h, respectively, in the presence of 1.5 µM Eg5i or 0.5 µM BafA1. Monoastral phenotypic cells were isolated from the bulk population of Eg5i-treated cells, whereas total cells were collected in the BafA1 treatment. Note that BafA1 treatment blocks acidification and capsid uncoating. Plasma membranes were mechanically disrupted, and the cell lysates were treated with 10 U of DNase I for 3 h in the presence or absence of TX-100. Total DNA was isolated and analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR). Data are reported as –Δ Ct normalized to DNA isolated from TX-100–treated samples. Note that the HPV16 genome is protected from DNase I digestion up to 6.99 ± 0.23 and 7.02 ± 0.18 Ct values in HaCaT and HeLa cells, respectively (n = 3). (C) HeLa cells were infected with HPV16 quasivirions encapsidating an HPV16 genome for 24 h in the presence of 1.5 µM Eg5i or 1 µM BafA1. Cells were collected and mechanically disrupted as described in B. Cell lysates were fractionated using a sucrose density gradient. DNA in the gradient fractions was amplified using HPV16 E6-specific primers by conventional PCR using dilutions of the gradient fractions as a template and visualized by gel electrophoresis. Purified HPV16 quasivirus was fractionated as a virus-only control. Note that the HPV16 genome is enriched in fraction 4 in the Eg5i-treated cells, whereas it is enriched in fraction 6 in BafA1-treated cells.

We next infected HaCaT and HeLa cells with HPV16 pseudovirus in the presence of Eg5i, mechanically disrupted the plasma membrane, and treated cell extracts with DNase I to digest all accessible DNA molecules. We observed that the majority of the pseudogenomes, but not cellular DNA, was protected from digestion but became susceptible after TX-100 treatment (Fig. 3B). When we blocked acidification and trafficking of HPV16-containing endocytic vesicles with BafA1, the viral genome was protected to a similar level (41, 42, 45).

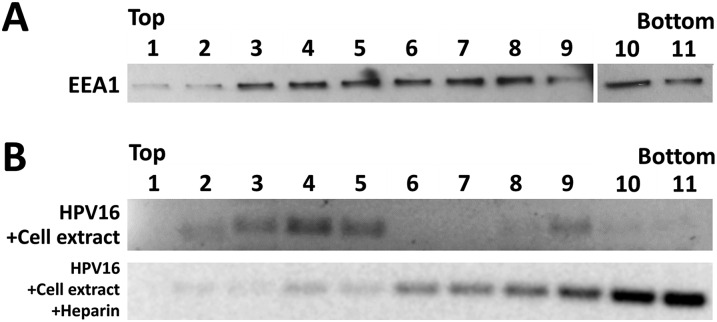

Further support for residence within a vesicular compartment during mitosis came from our flotation assays. At 18 hpi in the presence of Eg5i or BafA1, we generated cell extract from HeLa cells by mechanical disruption. Extracts were layered at the bottom of a sucrose step gradient, and during centrifugation, the HPV16 genome migrated up through the gradient, consistent with an association with lipids. Highly purified quasivirus alone remained near the bottom of the gradient (Fig. 3C). As a control, we demonstrated flotation of the early endosomal marker EEA1 from cell extract by Western blot analysis (Fig. S2A). When highly purified quasivirus was combined with cell extract, upward migration of the viral genome to higher fractions was unexpectedly observed. Preincubation of purified quasivirus with soluble heparin abolished this upward migration, suggesting that it was due to an interaction with heparan sulfates present on plasma membrane-derived vesicles (Fig. S2B). The relative density of DNA was distinct in BafA1- and Eg5i-treated samples, suggesting that the viral DNA resides in vesicles of differing natures.

Fig. S2.

Separation of vesicles via the sucrose flotation assay. (A) Uninfected HeLa cells were grown for 18 h, trypsinized, and then collected. Cellular homogenates were prepared by incubating cells on ice for 15 min in SFB (20 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EDTA) and then passing the cells 20 times through a 27-gauge needle. The PNS was adjusted to 40.6% sucrose in 1 mL total volume, and then placed into the bottom of an SW55 centrifuge tube. The sucrose flotation assay column was generated by overlaying the PNS with 2.5 mL of 35% sucrose, 1 mL of 25% sucrose, and 0.5 mL of 8.56% sucrose solution in SFB. Fractions of ∼425 µL were collected from the top after the column was spun down using a SW55 rotor for 40,000 rpm at 5 °C. The fractions were collected and probed for the presence of EEA1 by immunoblotting. Note that EEA1 is found in fractions near the top of the gradient. (B) Highly purified virus stock was combined with cell extract and subjected to the sucrose flotation assay as described in A. As a control, highly purified virus stock was preincubated with 100 µg/mL of heparin at 37 °C for 1 h, combined with cell extract, and subjected to sucrose flotation assay as described in A. Fractions were collected and used as a template for conventional PCR using E6-specific primers to detect the presence of the viral DNA. Note that preincubation with heparin blocked upward migration of the viral DNA.

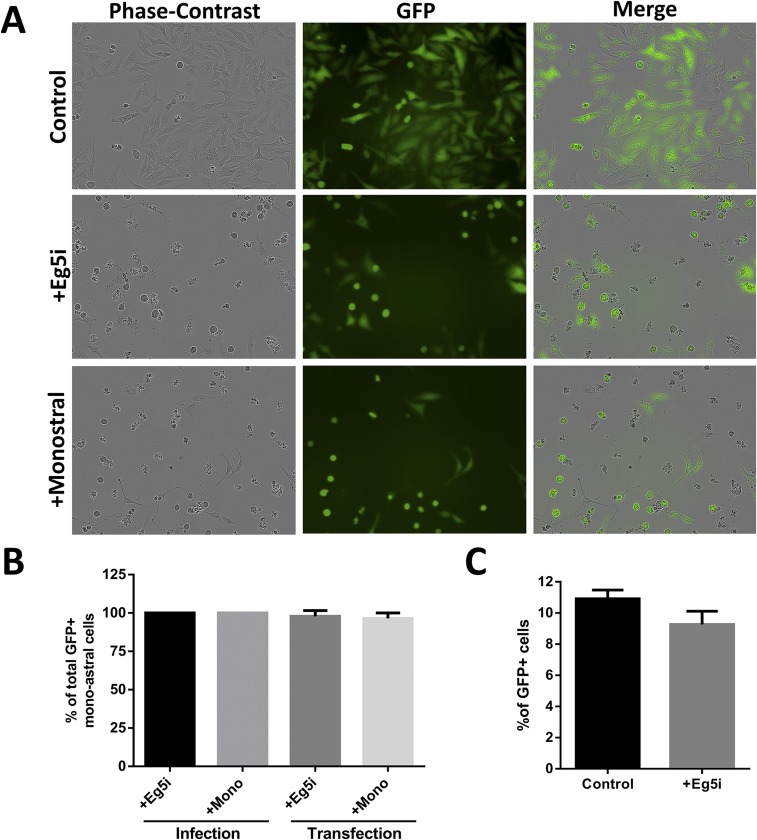

In contrast to our observations, a previous study reported that inhibition of Eg5 has no effect on pseudoviral infectivity in both HeLa and HaCaT cells (34). In line with that study, we also observed no significant inhibition of infection in the presence of Eg5i (Fig. S3C); however, we found a markedly reduced number of viable cells after 48 h (70.85% ± 3.75; n = 3) (Fig. S3A), raising the possibility that the GFP+ cells had escaped inhibition. To clarify this finding, we repeated the infection and monitored the GFP expression of individual cells using live-cell imaging. We observed that all cells expressing GFP had previously completed at least one round of mitosis (Movies S1 and S2), confirming that some cells can escape Eg5 inhibition. On the other hand, cells arrested in the monoastral phenotype never expressed GFP (Fig. S3B). The leakiness of Eg5 inhibition explains the apparent discrepancy of our observations with previously published infectivity data and provides further indirect evidence that the viral genome is retained in a vesicle during mitosis.

Fig. S3.

Arrest in mitosis with inhibitors of Eg5 is leaky. (A) HeLa cells were infected with HPV16 pseudovirus encapsidating a GFP expression plasmid pseudogenome for 72 h in the presence or absence of 1.5 µM Eg5i and 100 µM monastrol. Cells were monitored by live-cell imaging. Images from 48 h are presented here. Note that GFP expression is visible in cells that exhibit the monoastral phenotype. Also note that there are markedly less viable cells after 48 h in the Eg5-inhibited cells. (B) Quantification for the number of GFP+ monoastral phenotypic cells that have undergone at least one round of division before expressing GFP (∼30 cells counted per biological replicate; n = 3) as observed by live-cell imaging. Note that ∼100% of cells that enter the monoastral phenotype have undergone at least one round of mitosis before expressing GFP. (C) HeLa cells were infected with HPV16 pseudovirus for 48 h in the presence or absence of 1.5 µM Eg5i, and the number of GFP+ cells were counted by flow cytometry. Note that Eg5i treatment did not show any loss in infectivity as measured by FACS.

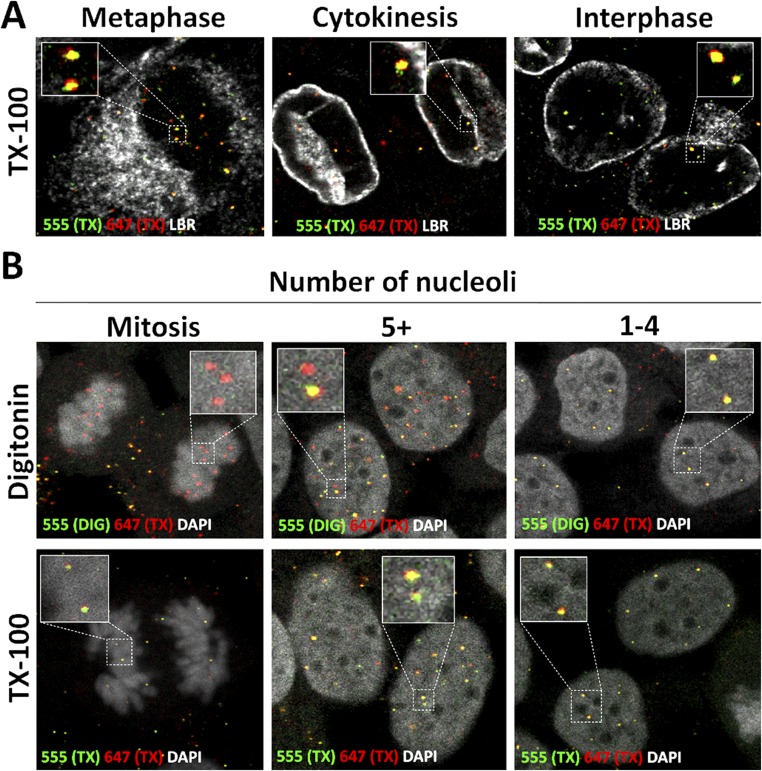

Release of the Viral Genome from the Vesicle Is Delayed.

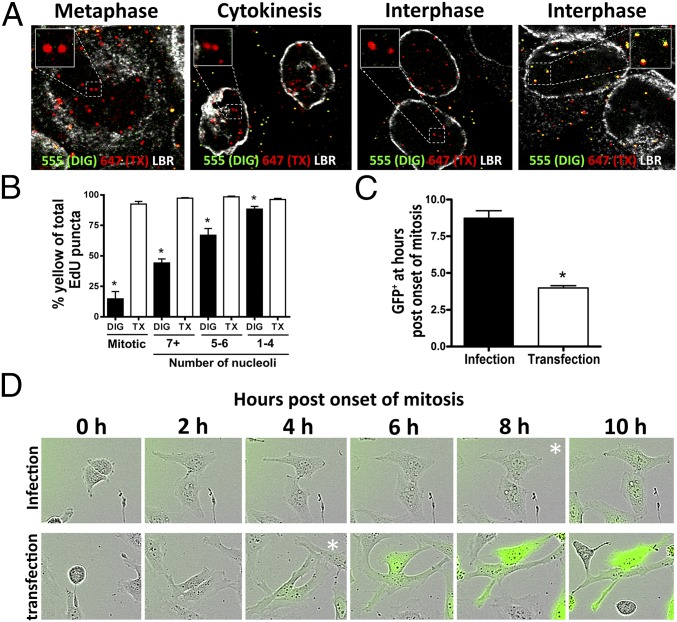

We observed that the viral genome remains inaccessible to AF555 dye in cells permeabilized with DIG in a minority of interphase cells (Fig. 4A), suggesting delayed egress from the putative transport vesicle. In controls, we observed dual staining with AF555 and AF647 in the TX-100–treated cells (Fig. S4A). To estimate the time it takes for the viral genome to become accessible after cytokinesis, we measured the number of nucleoli. In early G1 phase, a large number of smaller prenucleolar bodies are present that assemble to form the smaller number of larger nucleoli. In HeLa cells, this process takes ∼2 h after telophase (46, 47). Accessibility of the viral genome to AF555 after DIG treatment was inversely correlated with the number of nucleolar bodies observed (Fig. 4B and Fig. S4B).

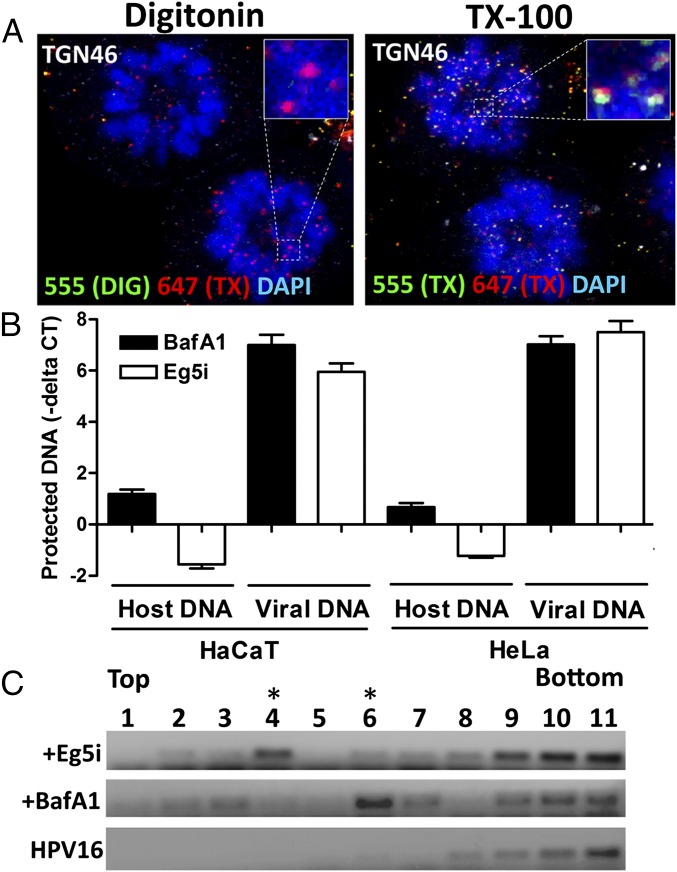

Fig. 4.

Release of the viral genome from the vesicle is delayed. (A) HaCaT cells were infected as described in Fig. 2 B and C. LBR (white) was stained after TX-100 treatment. Note the absence of AF555 staining within the nuclei of the DIG-treated cells in cytokinesis and some interphase cells. (B) Quantification of the AF555 accessibility as a percentage of total AF647 relative to the number of individual puncta per cell. The total number of nucleoli per cell was counted as well (∼50 cells counted per biological replicate, n = 3; mitotic, P < 0.0005; 7+ nucleoli, P < 0.0001; 5–6 nucleoli, P < 0.005; 1–4 nucleoli, P = 0.0303). Note that increased accessibility is inversely correlated with the number of nucleoli present per image slice. (C and D) HeLa cells were infected with HPV16 pseudovirus encapsidating pseudogenomes or transfected using MATra with pfwB plasmid for 72 h. Live-cell images were obtained once an hour. Cells were quantified by counting how long it took cells to display GFP expression following the onset of mitosis (50 cells counted per biological replicate, n = 3; P < 0.005). (D) Time lapse of HeLa cells from the onset of mitosis until display of GFP expression after delivery of pfwB by HPV16 pseudovirus and transfection with MATra reagent, respectively. Expression levels of GFP in the infection reached comparable levels to those of the transfection over time (Movie S3).

Fig. S4.

Pseudogenome becomes accessible during early interphase. (A) HaCaT cells were infected with EdU-labeled HPV16 pseudovirus for 24 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF555 (green) in Click-iT reaction buffer. Cells were fixed again, permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF647 (red) in Click-iT reaction buffer. LBR (white) was stained. Note that the pseudogenome was accessible to AF555 during cytokinesis and early interphase after TX-100 permeabilization. (B) HaCaT cells were infected with EdU-labeled HPV16 pseudovirus for 24 h and stained. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.625 µg/mL DIG, and treated with AF555 (green) in Click-iT reaction buffer. Then the cells were fixed again, permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF647 (red) in Click-iT reaction buffer. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (white). Note that the pseudogenomes exhibited limited accessibility to AF555 after DIG treatment in cells with five or more nucleoli.

To test whether delayed release is correlated with delayed GFP expression, we used the MATra transfection method, which requires mitosis for the DNA to enter the nucleus. We found that expression of the same marker plasmid delivered by HPV16 particles was delayed by ∼4 h compared with delivery by transfection (Fig. 4 C and D and Movies S3 and S4). Taken together, these data suggest that release from the vesicle is delayed after the completion of mitosis.

L2 Mediates Transport Along Microtubules During Mitosis.

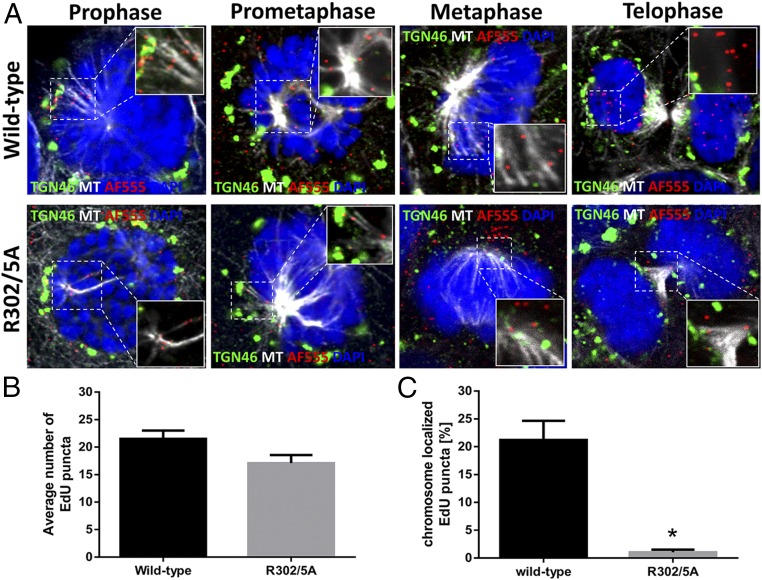

L2 protein has been demonstrated to interact with components of the dynein motor protein complex, opening up the possibility that virus-containing transport vesicles also use microtubule-mediated transport during mitosis (30, 31). Indeed, we found the incoming viral genome in close proximity to astral microtubules located between the TGN and the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) in prophase and prometaphase cells. During metaphase, we observed the viral genome next to spindle microtubules and/or the condensed chromosomes. In telophase cells, the viral genome was retained in the newly formed nuclei of dividing cells (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

The incoming viral genome associates with microtubules during mitosis, and L2 facilitates delivery to the nucleus. (A) HaCaT cells were infected for 24 h with pseudovirus harboring either WT 16L2 or 16L2-R302/5A that encapsidated an EdU-labeled pseudogenome. Cells were fixed, permeabilized in 0.5% TX-100, and treated with AF555 in Click-iT reaction buffer to detect the pseudogenomes (red). The TGN (green) or microtubules (MT; white) were stained as well. The nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Still images of cells in different stages of mitosis were collected. Note that the pseudogenome dissociated from TGN46 marker during prophase and associated with microtubules throughout mitosis. (B) Graphical representation of the average number of EdU puncta in three continuous Z-stack images per cell counted (n = 15 cells; P = 0.0431). (C) Graphical representation for the percentage of EdU puncta localized to condensed chromosomes of cells in different stages of mitosis for both the WT and mutant pseudoviruses. Quantification is based on the percentage of EdU puncta localized to condensed chromosomes out of the total number of EdU puncta per cell based on three continuous Z-stack images per cell counted (n = 15 cells; P < 0.0001).

We next asked whether the L2 protein is facilitating this transport. Our group and others have previously characterized several point mutations within the nuclear retention region of the L2 protein that are important for nuclear delivery of the viral genome (23, 48). EdU-labeled pseudovirus harboring mutant L2 protein (R302/5A) has been associated with astral microtubules in prophase and prometaphase like WT; however, despite infecting cells with similar amounts of visible EdU-labeled particles per cell (Fig. 5B), we found a dramatic loss of the viral genome associated with the condensed chromosomes during later stages of mitosis (Fig. 5C). By telophase, we observed a nearly complete loss of the viral genome from the nuclei of dividing cells in pseudovirus harboring the mutant L2 protein. Taken together, these data suggest that the viral genome dissociates from the TGN and transports along microtubules, and that L2 protein facilitates an association with condensed chromosomes.

Discussion

Here we have demonstrated that HPV resides and traffics in a vesicle throughout mitosis. Our conclusions are based on our findings that the viral genome is inaccessible to small-molecule dyes during all stages of mitosis, is protected from nuclease digestion, has low buoyant density in flotation gradients, displays delayed expression, and associates with microtubules during mitosis. Moreover, luminal epitopes of capsid proteins are inaccessible to antibodies during mitosis. Dye accessibility and delayed expression kinetics suggest that release from the putative transport vesicle inside the nucleus occurs after completion of mitosis and reestablishment of the nuclear envelope.

Our observations are somewhat contradictory to recently published findings purporting that arresting cells in a monoastral phenotype does not block HPV16 infection (34). However, a careful analysis reveals that Eg5 inhibition is leaky and that a minority of cells complete an additional cell cycle rather than being arrested in mitosis. Live-cell imaging demonstrated that only cells completing mitosis, and not those directly arrested in the monoastral phenotype, express GFP protein encoded by the pseudogenome. Cells that were directly arrested in mitosis died within the 48 h incubation period and were discarded during flow cytometry, giving the wrong impression that these inhibitors do not block infection. The prolonged treatment with inhibitors of mitosis without expression in arrested cells and nuclease resistance suggests that membranous structures protecting the viral genome are rather stable during mitosis.

Currently, we are unable to determine whether the viral genome is present within an HPV-induced transport vesicle or HPV is usurping a preexisting cellular pathway. Regardless, our data suggest that the L2 protein is important for directing the HPV-containing membranous structures toward the nucleus during mitosis. It was recently demonstrated that the L2 protein becomes transmembranous to engage numerous cytoplasmic factors required for trafficking to the TGN and possibly the ER, with some 30 N-terminal residues being luminal (28, 32). We have shown that L2 assumes a similar topography during mitosis, suggesting that HPV-harboring vesicles bud out of the TGN or the ER during the onset of mitosis. During cell division, the TGN and ER undergo reorganization and fragment into vesicles (49). This partitioning of the TGN and ER ensures that both compartments are equally distributed to the newly formed daughter cells. Therefore, it can be speculated that HPV takes advantage of this reorganization event to hijack a vesicle by using putative L2 interaction domains present on the cytosolic side of the membrane.

We also provide evidence that HPV-harboring vesicles traffic along microtubules. Initially, this seems to be a minus end-directed transport toward the MTOC. One possibility is that HPV uses dynein, which is known to bind to L2 protein, to facilitate trafficking (30, 31). Based on the association of HPV-harboring vesicles with spindle microtubules at later mitotic stages, we speculate that HPV migrates in a minus end- directed fashion along astral microtubules from the TGN to the MTOC. This is followed by plus end-directed transport along spindle microtubules from the spindle pole to condensed chromosomes, thus pointing to a switch in directionality. To date, however, live-cell imaging of late trafficking of HPV particles has been unsuccessful, precluding us from directly testing this idea.

Previous observations have suggested that L2 protein can associate with condensed chromosomes during mitosis (34); therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that L2 may interact directly with nuclear resident proteins or with the condensed chromosomes to ensure that the transport vesicle remains associated with the mitotic bodies until the completion of mitosis. We have provided evidence that the 16L2-R302/5A mutant protein is defective for deposition of HPV-harboring vesicles on condensed chromosomes. This would suggest that the mutation disrupts interactions with nuclear components. Indeed, the mutation disrupts the nuclear retention of overexpressed L2 (48). It is also conceivable that this mutant is incapable of plus end-directed transport, however. We previously reported that this mutation resulted in increased levels of viral genome in the TGN of interphase cells (23), and suggested that 16L2-R302/5A is defective for mediating egress from the TGN; however, given our finding of dissociation from the TGN in prophase, an alternative explanation for the phenotype of this mutant protein may be a lack of interaction with motor proteins mediating plus end-directed transport, such as kinesins. It may be speculated that the deficiency in kinesin interaction speeds up net minus end-directed transport, resulting in increased levels of viral genome at the TGN. Further studies are needed to address this idea.

The L2 protein inserts into the membrane shortly after internalization and uncoating to facilitate intracellular trafficking. Our data demonstrate that this is not sufficient to release the genome into the cytoplasm, suggesting the need for cellular factors not present in the endocytic compartment, including TGN and ER. In that regard, HPV16 is unlike adenovirus, which uses the viral protein VI to rupture the endocytic membranes (50). On the other hand, polyomaviruses take advantage of the ER-associated degradation system to translocate across the ER membrane (51, 52). Because HPV delays its release until after mitosis and nuclear envelope reformation, it is unlikely to use similar mechanisms. Given this delayed timing, we can assume that the HPV-harboring vesicles are not involved in early events of nuclear envelope reformation and might not fuse with the nuclear envelope, which would deliver the viral genome into the nuclear intermembrane space rather than to the nucleoplasm. There is no published evidence for the existence of intranuclear vesicles; as such, it is tempting to speculate that degradation pathways may exist to remove vesicles fortuitously ending up in the nucleus during mitosis. Indeed, a number of nuclear phospholipases are involved in the turnover of lipids, although their exact function inside the nucleus is not well understood (53).

Interestingly, siRNA screens have identified several phospholipases required for HPV infection (27, 34). Another nonenveloped virus, parvovirus, uses phospholipases to penetrate intracellular membranes. On entry into the endosome, low pH triggers the parvovirus virion to deploy a lipolytic enzyme, phospholipase A2, expressed on the N terminus of VP1, the minor coat protein, to egress into the cytoplasm (54). Considering that the HPV capsid proteins have no known enzymatic activity, it may be speculated that HPV instead takes advantage of cellular phospholipases for egress. A release based on degradation would be consistent with the observed time delay. The study of HPV genome release might provide insight into the host cell factors involved in related cellular processes.

Furthermore, viruses often usurp existing cellular pathways, and it is unlikely that the observed nuclear vesicles are HPV-specific. Thus, we may have uncovered a hitherto unrecognized pathway for delivering cargo to the nucleus. Clearly, more research is needed to fully understand the late trafficking events and egress of HPV and to explore the host cell factors essential for these events.

Materials and Methods

The LSU Health Shreveport’s Institutional Biosafety Committee approved all of the experiments reported herein (project no. B06-009; approval of update on December 10, 2015).

Immunofluorescent Microscopy Using Click-iT Reaction Chemistry After Selective Permeabilization.

HaCaT cells were grown on coverslips for 24 h to ∼50% confluency and infected with HPV16 pseudovirus encapsidating the EdU-labeled pseudogenome at ∼200–500 EdU puncta per cell in the presence or absence of inhibitors. After specified times after infection, the cells were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min at room temperature (RT), washed with PBS, and selectively permeabilized with 0.625 µg/mL of DIG in PBS for 10 min at RT. The cells were washed in PBS and blocked in 5% (wt/vol) normal goat serum (NGS) for 30 min. Cells were treated with the first round of AF555 in Click-iT reaction buffer for 30 min at RT protected from light. After washing in PBS, an optional incubation for 1 h with primary rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-TGN46 in 2.5% NGS at 37 °C was performed, followed by extensive washing with PBS and incubation with a secondary polyclonal antibody, goat anti-rabbit conjugated with AF488 in 2.5% NGS for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed extensively once more in PBS and fixed in 1% PFA for 5 min at RT. Cells were washed again in PBS and permeabilized using 0.5% TX-100 for 10 min at RT. After an extensive wash with PBS, cells were treated with a second round with AF647 in Click-iT reaction buffer for 30 min at RT protected from light. Cells were then washed extensively again in PBS, and an optional second round of primary and secondary antibody was used to detect Lamin B receptor (LBR), Laminin 33, or TGN46 in 2.5% NGS for 1 h each at 37 °C. Finally, the cells were washed in PBS and mounted with DAPI. Single slice images and Z-stacks were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5 spectral confocal microscope. All images from each individual experiment were acquired under the same laser power settings and enhanced uniformly in Adobe Photoshop and/or ImageJ.

Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Additional details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Generation of HPV16 Quasivirus and HPV16 Pseudovirus.

Pseudoviruses encapsidating a GFP expression plasmid, pfwB, were generated in the 293TT cell line as described previously using expression plasmid pShell16L1L2HA-3′ (37, 38, 55). The pfwB plasmid was a kind gift from John Schiller, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda. Codon-optimized L1 and L2 expression plasmids, described previously (56), were provided by Martin Müller, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, Heidelberg. Quasivirions encapsidating the HPV16 genome were generated by cotransfecting pShell16L1L2, a loxed HPV16 genome contained on pCMV-LoxP-HPV16-EGFP plasmid, and pBCre, a Cre recombinase expression plasmid, into 293TT cells as described previously (39). Viral DNA within the virions was isolated using NucleoSpin Blood QuickPure (740569.250; Macherey-Nagel) supplemented with 20 mM each EDTA and DTT. The genome copy number was quantified with qPCR and HPV16- or pfwB-specific primers. Pseudovirus preparations in our hands have a particle:infectivity ratio of 1:100–1:300. For pseudogenome detection by immunofluorescence microscopy, the growth medium during generation of pseudovirus was supplemented with 100 µM of EdU at 6 h posttransfection as described previously (40).

Generation of Vaccinia Virus Encapsidating an EdU-Labeled Genome.

The 293TT cells were infected with vaccinia virus, Western Reserve (WR) strain, at a multiplicity of infection of 1. At 2 hpi, the growth medium was supplemented with 25 µM EdU. After 24 hpi, cells were collected, supernatant was discarded, and the infected cells were resuspended in 1 mM Tris pH 9.0. Three freeze-thaw cycles were performed, followed by purification of virus via ultracentrifugation through a 36% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion at 20,000 rpm for 1 h using the Beckman SW41 rotor. The pellet was then resuspended in 500 µL of Tris pH 9.0.

Cell Lines.

The 293TT and HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. HaCaT cells were grown in low-glucose DMEM containing 5% FBS and antibiotics.

Antibodies and Other Reagents.

The L2 protein was detected with mouse monoclonal (mab) antibodies K4 and 33L2-1, which recognize epitopes within amino acids 20–38 and 163–170, respectively (32). The L1 protein was detected using mouse mab 33L1-7, which recognizes an epitope within amino acids 303–313 of the L1 protein (2). The TGN was detected using rabbit polyclonal antibody (pab) anti-TGN46, which that recognizes a luminal epitope within amino acid residues 200–350 (PA5-23068; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Laminin-332 (formally known as Laminin-5) was detected using rabbit pab anti–Laminin-5 (ab14509; Abcam). The nuclear envelope was detected using rabbit pab anti-LBR (ab32535; Abcam). The microtubule network was detected using mouse mab α-tubulin conjugated to AF488 (8058S; Cell Signaling). The primary antibodies were detected using goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse AF488-conjugated secondary antibody (A-11034 and A-11029, respectively; Invitrogen). The Click-iT EdU Imaging Kits for AF555 and AF647 (C10338 and C10340, respectively; Invitrogen) were used for specific detection of the EdU-labeled genome and pseudogenome. The nuclei of cells were stained with ProLong Gold and SlowFade Antifade containing DAPI (P36931; Invitrogen). Pab rabbit anti-EEA1 (E3906; Sigma-Aldrich) was used for Western blots in the flotation assay.

Inhibitors.

All inhibitors were purchased from Calbiochem. Cells were arrested in the monoastral phenotype with 1.5 µM Eg5 inhibitor III (dimethylenastron; 324622) and 100 µM monastrol (475879). Bafilomycin A1 (196000) was used to block acidification of endosomes during staining and the flotation assay at indicated concentrations. Nocodazole (487928) was used in the flotation assay.

Immunofluorescent Microscopy Using Primary Antibodies After Selective Permeabilization.

HaCaT cells were grown on coverslips for 24 h to ∼50% confluency and infected with HPV16 pseudovirus encapsidating EdU-labeled pseudogenome at ∼200–500 EdU puncta per cell. After 24 hpi, the cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min at RT, washed with pH 7.5 PBS, and selectively permeabilized with 5 µg/mL DIG in ddH20 for 10 min at RT. The cells were then washed in PBS and blocked in 5% NGS for 30 min, then incubated with Click-iT reaction mixture without AF to denature the capsids. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by an extensive washing in PBS.

Next, the cells were incubated with a secondary pab anti-rabbit conjugated with AF488 or AF647, then once again washed extensively in PBS and fixed in 1% PFA for 5 min at RT. The cells were permeabilized using 0.5% TX-100 for 10 min at RT. After a brief wash with PBS, cells were treated with the Click-iT reaction buffer with AF555 for 30 min at RT protected from light. Cells were again washed extensively in PBS and mounted with DAPI. Single slice images and Z-stacks were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5 spectral confocal microscope. All images from each individual experiment were acquired under the same laser power settings and enhanced uniformly in Adobe Photoshop and/or ImageJ.

For immunofluorescent microscopy, HaCaT cells were grown on coverslips for 24 h to ∼50% confluency and then infected with HPV16 pseudovirus encapsidating EdU-labeled pseudogenome at approximately ∼200–500 EdU particles per cell. After 24 hpi, the cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min at RT, washed with PBS, and permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100 in PBS for 10 min at RT. After another washing in PBS and blocking in 5% NGS for 30 min, the cells were incubated with the Click-iT reaction mixture with AF555 for 30 min at RT protected from light.

The cells were then washed extensively and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by another extensive wash in PBS and incubation with a secondary pab anti-rabbit conjugated to AF488 or 647. Cells were once again extensively washed in PBS and mounted with DAPI. Single slice images and Z-stacks were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5 spectral confocal microscope. All images from each individual experiment were acquired under the same laser power settings and enhanced uniformly in Adobe Photoshop and/or ImageJ.

Separation of Virus-Containing Vesicles via the Sucrose Flotation Assay.

HeLa cells were grown to ∼80% confluency in T150 flasks and then infected with HPV16 quasivirions for 18 h in the presence of either 1 µM BafA1 or 1.5 µM Eg5 inhibitor III. In addition, 10 µM nocodazole was added to the cell medium at 17 h. The cells were then washed with PBS (pH 7.5), incubated with alkaline phosphate buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4, 1.37 M NaCl, and 53.7 mM KCl, pH 10.25) for 2 min, and washed again several times with PBS. To selectively remove monoastral cells from the bulk population, cells were treated with diluted trypsin solution for ∼2 min. Monoastral phenotypic cells were isolated from the bulk population by gently tapping them off the flasks and collecting the supernatant. The same procedure was followed for the BafA1-treated samples, except that the total cell population was collected for these samples.

Cellular homogenates were prepared by incubating cells on ice for 15 min in subcellular fractionation buffer (SFB; 20 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EDTA) and then passing the cells 20 times through a 27-gauge needle. The homogenates were centrifuged to generate postnuclear supernatant (PNS), which was then adjusted to 40.6% sucrose in 1 mL total volume, and then placed into the bottom of a SW55 centrifuge tube (Beckman Coulter; 331372). The sucrose flotation assay column was generated by overlaying the PNS with 2.5 mL of 35% sucrose, 1 mL of 25% sucrose, and 0.5 mL of 8.56% sucrose solution in SFB. Fractions of ∼410 µL were collected from the top after the column was spun down for 3 h using a SW55 rotor at 40,000 rpm and 5 °C. The fractions were probed for the presence of HPV genome by conventional PCR, using HPV16-specific E6 primers, with products visualized on a 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel.

To confirm that the sucrose flotation assay successfully separated vesicular structures based on buoyancy, uninfected HeLa cells were lysed and subjected to the sucrose flotation assay as described above. The marker for vesicles and endosomes, EEA1, was probed for in these fractions via Western blot analysis as described previously (57). As a control, highly purified virus stock was preincubated with 100 µg/mL of heparin at 37 °C for 1 h or directly added to cell extract and subjected to the flotation assay as described above.

DNase Protection Assay.

HeLa and HaCaT cells were grown to 80% confluency in 10-cm dishes and infected with HPV16 pseudovirus for 18 and 24 h, respectively, in the presence of either 0.5 µM BafA1 or 1.5 µM Eg5 inhibitor III. At 6 hpi, cells were washed with PBS and high-pH buffer to inactivate cell surface-resident virus. HeLa and HaCaT cells were cultured in fresh medium supplemented with the appropriate inhibitors and DNase I for another 12 h and 18 h, respectively. Monoastral phenotypic HaCaT cells were isolated from the bulk population by a 1-min treatment with diluted trypsin and gently tapped off the dish, after which the supernatant was collected. Monoastral phenotypic HeLa cells were isolated from the bulk population by gently tapping the cells off the dish. The total cell population was collected in the BafA1-treated samples. Cells were resuspended in PBS plus 1 mM DTT and then passed 40 times through a 27-gauge needle.

Homogenates were treated with DNase I (M0303S; New England BioLabs) for 3 h at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 0.5% TX-100 detergent. The reaction was stopped by adding 1× stop buffer (5 mM EDTA), followed by incubation at 65 °C for 10 min. Next, homogenates were treated with 0.2% SDS, proteinase K, and RNase A overnight, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction of DNA. Isolated DNA was analyzed by qPCR using pfwB- and β-actin–specific primers.

Infection Assay.

HeLa cells were grown overnight at 37 °C in a 24-well plate to 30–50% confluency, then infected with HPV16 pseudovirus in the presence or absence of 1.5 µM Eg5 inhibitor III. After 48 hpi, cells were collected, and GFP+ cells were counted using a BD FACSCalibur analyzer. In addition, the cell suspension from the above experiment was combined in a 1:1 ratio with 0.4% trypan blue solution (25–900-cl; CellGro) and the numbers of trypan blue-positive and -negative cells were counted using a hemocytometer.

Live-Cell Imaging.

HeLa cells were grown overnight at 37 °C in a 24-well plate to 30–50% confluency and then infected with HPV16 pseudovirus in the presence or absence of 1.5 µM Eg5 inhibitor III or 100 µM monastrol. Plates were incubated in the IncuCyte ZOOM system (Essen Bioscience) at 37 °C. Images were obtained every hour for up to 72 h for both phase-contrast and GFP excitation. Composite images were compiled into movies depicting hours 9–48. Individual cells were quantified by determining the difference in time between the onset of mitosis and visual GFP expression per cell, with 50 cells counted per biological replicate (n = 3).

Transfection.

HeLa cells were grown overnight at 37 °C in a 24-well plate to 30–50% confluency. Then 700 ng of pfwB plasmid DNA was incubated with 0.7 µL of MATra reagent in 100 µL of Corning SF Medium (40-101-CV) for 30 min at RT. The HeLa cells were transfected by adding 100 µL of the MATra transfection reagent and DNA mixture to 500 µL of DMEM on the HeLa cells in the 24-well plate. The plates were incubated on a MATra magnet for 15 min at RT, followed by the addition of another 400 µL of DMEM. Transfected cells were immediately placed in the IncuCyte ZOOM at 37 °C for image acquisition as described above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Müller and John Schiller for providing reagents and Rona Scott and Lindsey Hutt-Fletcher for engaging in helpful discussions and reading the manuscript. This project was supported by Grants R01 AI081809 (to M.J.S.) and R01 DE0166908S1 (PI: Lindsey Hutt-Fletcher; co-PI: M.J.S. and Rona S. Scott) from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Institutes of Dental and Cranofacial Research and by Grant P20GM103433from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Additional support was provided by the Feist Weiller Cancer Center. S.D. was supported by a Carroll Feist predoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1600638113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Paludan SR, Bowie AG. Immune sensing of DNA. Immunity. 2013;38(5):870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bienkowska-Haba M, Williams C, Kim SM, Garcea RL, Sapp M. Cyclophilins facilitate dissociation of the human papillomavirus type 16 capsid protein L1 from the L2/DNA complex following virus entry. J Virol. 2012;86(18):9875–9887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00980-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buck CB, et al. Arrangement of L2 within the papillomavirus capsid. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5190–5197. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02726-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck CB, Pastrana DV, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Generation of HPV pseudovirions using transfection and their use in neutralization assays. Methods Mol Med. 2005;119:445–462. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-982-6:445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modis Y, Trus BL, Harrison SC. Atomic model of the papillomavirus capsid. EMBO J. 2002;21(18):4754–4762. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klug A, Finch JT. Structure of viruses of the papilloma-polyoma type, I: Human wart virus. J Mol Biol. 1965;11:403–423. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knappe M, et al. Surface-exposed amino acid residues of HPV16 L1 protein mediating interaction with cell surface heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(38):27913–27922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giroglou T, Florin L, Schäfer F, Streeck RE, Sapp M. Human papillomavirus infection requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J Virol. 2001;75(3):1565–1570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1565-1570.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joyce JG, et al. The L1 major capsid protein of human papillomavirus type 11 recombinant virus-like particles interacts with heparin and cell-surface glycosaminoglycans on human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(9):5810–5822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selinka HC, et al. Inhibition of transfer to secondary receptors by heparan sulfate-binding drug or antibody induces noninfectious uptake of human papillomavirus. J Virol. 2007;81(20):10970–10980. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00998-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culp TD, Budgeon LR, Christensen ND. Human papillomaviruses bind a basal extracellular matrix component secreted by keratinocytes which is distinct from a membrane-associated receptor. Virology. 2006;347(1):147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards KF, Bienkowska-Haba M, Dasgupta J, Chen XS, Sapp M. Multiple heparan sulfate binding site engagements are required for the infectious entry of human papillomavirus type 16. J Virol. 2013;87(21):11426–11437. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01721-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day PM, Schiller JT. The role of furin in papillomavirus infection. Future Microbiol. 2009;4(10):1255–1262. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Day PM. Cleavage of the papillomavirus minor capsid protein, L2, at a furin consensus site is necessary for infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(5):1522–1527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508815103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schelhaas M, et al. Entry of human papillomavirus type 16 by actin-dependent, clathrin- and lipid raft-independent endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002657. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spoden G, et al. Clathrin- and caveolin-independent entry of human papillomavirus type 16: Involvement of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs) PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheffer KD, Berditchevski F, Florin L. The tetraspanin CD151 in papillomavirus infection. Viruses. 2014;6(2):893–908. doi: 10.3390/v6020893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheffer KD, et al. Tetraspanin CD151 mediates papillomavirus type 16 endocytosis. J Virol. 2013;87(6):3435–3446. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02906-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abban CY, Meneses PI. Usage of heparan sulfate, integrins, and FAK in HPV16 infection. Virology. 2010;403(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon CS, Kim KD, Park SN, Cheong SW. alpha(6) integrin is the main receptor of human papillomavirus type 16 VLP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283(3):668–673. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evander M, et al. Identification of the alpha6 integrin as a candidate receptor for papillomaviruses. J Virol. 1997;71(3):2449–2456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2449-2456.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surviladze Z, Dziduszko A, Ozbun MA. Essential roles for soluble virion-associated heparan sulfonated proteoglycans and growth factors in human papillomavirus infections. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(2):e1002519. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiGiuseppe S, Bienkowska-Haba M, Hilbig L, Sapp M. The nuclear retention signal of HPV16 L2 protein is essential for incoming viral genome to transverse the trans-Golgi network. Virology. 2014;458-459:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bienkowska-Haba M, Patel HD, Sapp M. Target cell cyclophilins facilitate human papillomavirus type 16 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(7):e1000524. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergant M, Banks L. SNX17 facilitates infection with diverse papillomavirus types. J Virol. 2013;87(2):1270–1273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01991-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergant Marušič M, Ozbun MA, Campos SK, Myers MP, Banks L. Human papillomavirus L2 facilitates viral escape from late endosomes via sorting nexin 17. Traffic. 2012;13(3):455–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipovsky A, et al. Genome-wide siRNA screen identifies the retromer as a cellular entry factor for human papillomavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(18):7452–7457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302164110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popa A, et al. Direct binding of retromer to human papillomavirus type 16 minor capsid protein L2 mediates endosome exit during viral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(2):e1004699. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day PM, Thompson CD, Schowalter RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Identification of a role for the trans-Golgi network in human papillomavirus 16 pseudovirus infection. J Virol. 2013;87(7):3862–3870. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03222-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Florin L, et al. Identification of a dynein interacting domain in the papillomavirus minor capsid protein l2. J Virol. 2006;80(13):6691–6696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00057-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider MA, Spoden GA, Florin L, Lambert C. Identification of the dynein light chains required for human papillomavirus infection. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13(1):32–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiGiuseppe S, et al. Topography of the human papillomavirus minor capsid protein l2 during vesicular trafficking of infectious entry. J Virol. 2015;89(20):10442–10452. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01588-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W, Kazakov T, Popa A, DiMaio D. Vesicular trafficking of incoming human papillomavirus 16 to the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum requires γ-secretase activity. MBio. 2014;5(5):e01777–e14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01777-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aydin I, et al. Large-scale RNAi reveals the requirement of nuclear envelope breakdown for nuclear import of human papillomaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(5):e1004162. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pyeon D, Pearce SM, Lank SM, Ahlquist P, Lambert PF. Establishment of human papillomavirus infection requires cell cycle progression. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(2):e1000318. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cubie HA. Diseases associated with human papillomavirus infection. Virology. 2013;445(1-2):21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buck CB, Pastrana DV, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Efficient intracellular assembly of papillomaviral vectors. J Virol. 2004;78(2):751–757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.751-757.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buck CB, Thompson CD, Pang YY, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Maturation of papillomavirus capsids. J Virol. 2005;79(5):2839–2846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2839-2846.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JH, et al. Propagation of infectious human papillomavirus type 16 by using an adenovirus and Cre/LoxP mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(7):2094–2099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308615100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishii Y, et al. Inhibition of nuclear entry of HPV16 pseudovirus-packaged DNA by an anti-HPV16 L2 neutralizing antibody. Virology. 2010;406(2):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engel S, et al. Role of endosomes in simian virus 40 entry and infection. J Virol. 2011;85(9):4198–4211. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02179-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selinka HC, Giroglou T, Sapp M. Analysis of the infectious entry pathway of human papillomavirus type 33 pseudovirions. Virology. 2002;299(2):279–287. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moss B. Poxvirus entry and membrane fusion. Virology. 2006;344(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu M, et al. Inhibition of the mitotic kinesin Eg5 up-regulates Hsp70 through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in multiple myeloma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(26):18090–18097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bayer N, et al. Effect of bafilomycin A1 and nocodazole on endocytic transport in HeLa cells: Implications for viral uncoating and infection. J Virol. 1998;72(12):9645–9655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9645-9655.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernandez-Verdun D. Assembly and disassembly of the nucleolus during the cell cycle. Nucleus. 2011;2(3):189–194. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.3.16246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muro E, et al. The traffic of proteins between nucleolar organizer regions and prenucleolar bodies governs the assembly of the nucleolus at exit of mitosis. Nucleus. 2010;1(2):202–211. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.2.11334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mamoor S, et al. The high-risk HPV16 L2 minor capsid protein has multiple transport signals that mediate its nucleocytoplasmic traffic. Virology. 2012;422(2):413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shima DT, Haldar K, Pepperkok R, Watson R, Warren G. Partitioning of the Golgi apparatus during mitosis in living HeLa cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(6):1211–1228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H, Gerace L, Nemerow GR. Adenovirus protein VI mediates membrane disruption following capsid disassembly. J Virol. 2005;79(4):1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.1992-2000.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inoue T, Tsai B. A large and intact viral particle penetrates the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to reach the cytosol. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(5):e1002037. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rainey-Barger EK, Magnuson B, Tsai B. A chaperone-activated nonenveloped virus perforates the physiologically relevant endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Virol. 2007;81(23):12996–13004. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01037-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faenza I, Fiume R, Piazzi M, Colantoni A, Cocco L. Nuclear inositide specific phospholipase C signaling: Interactions and activity. FEBS J. 2013;280(24):6311–6321. doi: 10.1111/febs.12450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farr GA, Zhang LG, Tattersall P. Parvoviral virions deploy a capsid-tethered lipolytic enzyme to breach the endosomal membrane during cell entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(47):17148–17153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508477102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buck CB, Thompson CD. Production of papillomavirus-based gene transfer vectors. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2007;Chap. 26:Unit 26.1. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb2601s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leder C, Kleinschmidt JA, Wiethe C, Müller M. Enhancement of capsid gene expression: Preparing the human papillomavirus type 16 major structural gene L1 for DNA vaccination purposes. J Virol. 2001;75(19):9201–9209. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9201-9209.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobayashi T, et al. Separation and characterization of late endosomal membrane domains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(35):32157–32164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.