Significance

We identify a consistent reduction in the clarity and vividness of people’s memory of their past unethical actions, which explains why they behave dishonestly repeatedly over time. Across nine studies using diverse sample populations and more than 2,100 participants, we find that, as compared with people who engaged in ethical behavior and those who engaged in positive or negative actions, people who acted unethically are the least likely to remember the details of their actions. That is, people experience unethical amnesia: unethical actions tend to be forgotten and, when remembered, memories of unethical behavior become less clear and vivid over time than memories of other types of behaviors. Our findings advance the science of dishonesty, memory, and decision making.

Keywords: dishonesty, memory, unethical behavior, psychological dissonance, morality

Abstract

Despite our optimistic belief that we would behave honestly when facing the temptation to act unethically, we often cross ethical boundaries. This paper explores one possibility of why people engage in unethical behavior over time by suggesting that their memory for their past unethical actions is impaired. We propose that, after engaging in unethical behavior, individuals’ memories of their actions become more obfuscated over time because of the psychological distress and discomfort such misdeeds cause. In nine studies (n = 2,109), we show that engaging in unethical behavior produces changes in memory so that memories of unethical actions gradually become less clear and vivid than memories of ethical actions or other types of actions that are either positive or negative in valence. We term this memory obfuscation of one’s unethical acts over time “unethical amnesia.” Because of unethical amnesia, people are more likely to act dishonestly repeatedly over time.

Across the globe, dishonesty is a widespread and common phenomenon. On an all-too-regular basis, the news reports cases of ethical misconduct in business, politics, sports, education, and medicine, behaviors that cost society millions, possibly billions, of dollars every year. Although certainly worrisome, these actions account for only a small portion of the dishonesty present in societies across the globe. Many people who consider themselves honest nevertheless often cheat on taxes, steal from the workplace, illegally download music from the internet, have extramarital affairs, use public transportation for free, lie, and so on. The costs of such arguably small-scale dishonesty are surprisingly large, both socially and financially.

These troubling data explain, at least in part, why scholars across disciplines ranging from law and economics to psychology and management have become increasingly interested in studying when and why people, even those who report that they value morality, often act unethically (1). To date, this research has focused largely on identifying situational pressures that can sway a person’s moral compass (2) and on examining how individual differences predict various forms of unethical behavior (3).

Despite the many insights such work has provided, we still know little about why people engage in unethical behavior repeatedly over time. Because dishonesty often results in guilt, remorse, or other negative emotions (4), we might expect that people would avoid continuing to act unethically. However, anecdotal evidence across the domains highlighted earlier suggests just the opposite. Here, we identify one possible reason for persistent dishonesty: Unethical actions tend to be forgotten; when remembered, memories of unethical behavior become less clear and vivid over time than those of ethical actions or other types of positive and negative behaviors.

Despite the common belief people hold that they are more ethical and fairer than others (5) and their strong desire to maintain a positive self-image, when facing the opportunity to act unethically, they often do so, if only by a little bit (1, 6). Because people hold an overly positive view of their morality but consistently fail to live up to this standard, they experience psychological discomfort after behaving dishonestly and engage in various strategies to alleviate this dissonance and reduce their distress. For instance, individuals come up with justifications for their unethical behavior to distance themselves from it (7) or view it as morally permissible—for example, by dehumanizing the victims of their dishonesty (8). That is, they recode their action by morally disengaging. In fact, people’s unethical acts lead them to disengage morally by judging wrongdoing as less morally problematic than they would otherwise (7). Additionally, to reduce the psychological discomfort experienced after committing unethical acts, people use a double-distancing mechanism, judging others’ transgressions more harshly than their own and presenting themselves as more virtuous and ethical in comparison (9).

Another strategy people use, we suggest, is forgetting the details of their unethical actions over time. Such information, in fact, threatens their moral self-image and creates distress. An extensive body of research has documented that people actively forget some of their past behavior when doing so is convenient or makes them feel good (10). In the case of dishonesty, laboratory studies show that guilty participants can suppress retrieval of their crimes when instructed to do so. In fact, in such situations the brain activity of those who committed crimes is indistinguishable from that of innocent people (11, 12).

More generally, we argue, people experience what we refer to as “unethical amnesia”: Their memory of their past unethical behavior becomes less clear, less detailed, and less vivid over time than their memory of their ethical actions and of actions unrelated to ethics. Because people value morality and want to maintain a positive moral self-image (5) but often act dishonestly when facing the temptation to behave unethically (6), they are motivated to forget the details of their actions so that they can keep thinking of themselves as honest individuals. Previous findings suggest that the motivation to forget an event can disrupt the encoding of that event and reduces a person’s ability to recall that event in the future (10). In addition, people forget negative emotional events more easily than neutral ones (10). Thus, when people want forget a certain event, their memory of the details of the event is more likely to be impaired than when they do not have such a desire or intend to remember the event. In the case of unethical behavior, this desire to forget may lead people not to think about their unethical actions very often. As a result, they feel better (e.g., their discomfort is lower later on) and can maintain their moral self-concept intact. In addition, their memories of such actions become fuzzier over time.

To examine whether people experience unethical amnesia, we conducted nine studies that use a variety of methods and sample populations. In our studies, we compare people’s memory for their unethical acts with their memory of other events, including neutral, negative, and positive ones, and with their memory of others’ unethical actions. Our results show that people’s memory for their unethical actions is impaired and offer an explanation for why people repeatedly engage in dishonest behavior over time.

Results

Studies 1a and 1b: Autobiographical Memory of One’s Past Actions.

In our first two studies, we rely on individuals’ past experiences to examine their memory for their unethical acts compared with other moral and nonmoral acts. In study 1a, we randomly assigned participants (n = 400) to write about one of their personal past experiences: unethical, ethical, positive, negative, or neutral. Afterward, we measured their memory using items adapted from the Memory Characteristics Questionnaire (MCQ) (13). The MCQ assesses various qualitative characteristics of one’s memory. We focused on two dimensions: clarity (how vividly a person remembers an event) and thoughts and feelings (how a person remembers the feelings and thoughts experienced during the event). For clarity of one’s own memory, participants rated four items (α = 0.86) on a seven-point scale, e.g., “My memory of this event is dim (1) to sharp/clear (7).” We measured thoughts and feelings with two items (α = 0.64) rated on a seven-point scale (1) not at all to (7) clearly, including “I remember how I felt at the time I just recalled.” Next, respondents reported how they felt while describing the event by indicating their emotions (e.g., bad or good, sad or happy).

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) using participants’ ratings for all measures (clarity, thoughts and feelings, and various emotions) as dependent variables and condition as a between-subjects factor revealed a significant effect of condition [F(8, 391) = 12.82, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.21]. Similarly, univariate tests revealed significant differences among conditions on both clarity [F(4, 395) = 6.14, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06] and thoughts and feelings [F(4, 395) = 11.08, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10] (Table S1).

Table S1.

Means (SDs) of responses by condition in study 1a

| Measures | Unethical | Ethical | Negative | Positive | Neutral |

| Clarity | 5.38 (1.17)a | 6.00 (0.88)b | 5.90 (0.91)b | 5.99 (0.86)b | 5.98 (0.90)b |

| Sensory | 3.07 (1.60)a | 3.53 (1.56)a,b | 3.14 (1.69)a | 3.53 (1.83)a,b | 3.83 (1.85)b |

| Time context | 4.84 (1.29)a | 5.42 (1.32)b | 5.38 (1.41)b | 5.61 (1.30)b | 5.69 (1.22)b |

| Spatial context | 5.53 (1.18)a | 5.91 (1.07)b | 5.70 (1.09)a,b | 5.97 (0.97)b,c | 6.17 (0.81)c |

| Thoughts and feelings | 5.07 (1.07)a | 5.92 (1.02)b | 5.61 (0.97)c | 5.96 (0.85)b | 5.35 (1.16)a,c |

| Intensity of feelings | 4.64 (1.39)a | 5.25 (1.30)b | 5.27 (1.44)b | 5.30 (1.37)b | 3.89 (1.55)c |

| Timing | 7.86 (1.77)a | 7.86 (1.34)a | 7.73 (1.66)a | 7.51 (1.99)a | 2.54 (1.16)b |

| Positive affect | 2.37 (0.92)a | 3.06 (0.97)b | 2.43 (0.77)a | 2.99 (0.85)b | 2.83 (0.84)b |

| Negative affect | 1.73 (0.82)a | 1.25 (0.37)b | 1.73 (0.79)a | 1.31 (0.54)b | 1.31 (0.54)b |

| Bad–good | 4.23 (1.69)a | 5.65 (1.37)b | 4.48 (1.64)a | 5.85 (1.27)b | 5.56 (1.29)b |

| Sad–happy | 4.12 (1.71)a | 5.48 (1.57)b | 4.17 (1.63)a | 5.73 (1.28)b | 5.46 (1.40)b |

| Tense–relaxed | 4.36 (1.84)a | 5.42 (1.61)b | 4.56 (1.66)a | 5.79 (1.32)b | 5.47 (1.57)b |

| Negative–positive | 4.32 (1.67)a | 5.64 (1.40)b | 4.37 (1.60)a | 5.89 (1.30)b | 5.53 (1.43)b |

| Uncomfortable–comfortable | 4.58 (1.77)a | 5.60 (1.38)b | 4.78 (1.71)a | 5.91 (1.20)b | 5.69 (1.39)b |

| Distressed–satisfied | 4.33 (1.71)a | 5.57 (1.50)b | 4.39 (1.53)a | 5.60 (1.32)b | 5.03 (1.61)b |

| Time spent on writing (in seconds) | 227.29 (137.43)a | 271.24 (178.81)a,b | 285.63 (178.55)b | 256.94 (156.08)a,b | 248.65 (159.09)a,b |

| Number of words | 107.46 (61.14)a | 125.36 (75.31)a,b | 134.09 (81.49)b | 105.21 (59.70)a,c | 112.79 (68.05)a,b |

Means not sharing subscripts within rows are significantly different at P < 0.05 based on Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc paired comparisons.

Importantly, memory scores were lower in the unethical condition than in the negative condition on both clarity [mean (M)unethical = 5.38 vs. Mnegative = 5.90] and thoughts and feelings (Munethical = 5.07 vs. Mnegative = 5.61). The unethical and negative conditions did not differ on any of the self-reported emotions or on affect (all F’s <1). These results suggest that the intensity of the emotions participants felt during memory recollection while writing their essays was as expected and did not differ between negative and unethical conditions (Table S1).

Together, these results provide initial evidence that individuals’ memories of their own past unethical acts are less clear and less vivid than their memories of their ethical acts and their memories of positive, negative, and neutral experiences.

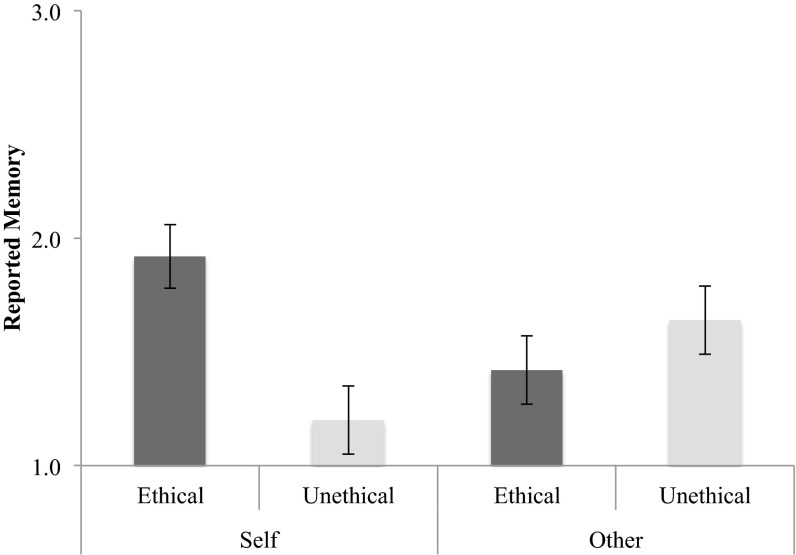

In study 1b, we randomly assigned participants (n = 343) to write about their own past ethical or unethical actions or the unethical or ethical behavior of someone else. Afterward, all participants rated their memory of the experience using the same MCQ items as in study 1a (clarity, α = 0.89; thoughts and feelings, α = 0.61). Participants also reported how they felt, using all the emotions included in study 1a as descriptors.

A MANOVA using participants’ ratings for all measures (clarity, thoughts and feelings, and various emotions) as dependent variables and actor and nature of the act as between-subjects factors showed a significant main effect for both actor [F(8, 332) = 2.71, P = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.06] and nature of the act [F(8, 332) = 11.46, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.22]. The analysis also yielded a significant interaction effect [F(8, 332) = 1.96, P = 0.050, ηp2 = 0.05] (Table S2).

Table S2.

Means (SDs) of responses by condition in study 1b

| Measures | Unethical-self | Ethical-self | Unethical-other | Ethical-other |

| Clarity | 5.58 (1.19)a | 6.07 (0.81)b | 5.54 (1.11)a | 5.55 (1.13)a |

| Sensory | 2.74 (1.38)a | 3.57 (1.46)b | 2.67 (1.29)a | 2.80 (1.43)a |

| Time context | 5.66 (1.13)a | 6.08 (0.91)b | 5.44 (1.32)a,c | 5.38 (1.51)a,b |

| Spatial context | 4.89 (1.75)a | 5.49 (1.34)b | 4.69 (1.61)a | 5.21 (1.47)a |

| Thoughts and feelings | 5.49 (0.98)a | 5.93 (0.84)b | 5.38 (1.28)a | 5.24 (1.21)a |

| Intensity of feelings | 5.02 (1.39)a | 5.27 (1.36)a | 5.02 (1.37)a | 4.55 (1.39)b |

| Timing | 7.98 (1.73)a | 7.73 (1.64)a | 8.09 (1.37)a | 7.00 (1.77)b |

| Positive affect | 2.37 (0.92)a | 3.06 (0.97)b | 2.59 (0.88)c | 2.87 (0.80)b |

| Negative affect | 1.73 (0.82)a | 1.25 (0.37)b,c | 1.55 (0.73)b | 1.32 (0.52)c |

| Bad–good | 3.84 (1.89)a | 5.66 (1.43)b | 4.68 (1.60)c | 5.60 (1.32)b |

| Sad–happy | 3.66 (1.89)a | 5.49 (1.56)b | 4.29 (1.72)c | 5.36 (1.57)b |

| Tense–relaxed | 4.13 (1.94)a | 5.42 (1.60)b | 4.59 (1.83)a | 5.34 (1.69)b |

| Negative–positive | 3.87 (1.78)a | 5.73 (1.40)b | 4.34 (1.84)c | 5.72 (1.47)b |

| Uncomfortable–comfortable | 3.93 (2.01)a | 5.51 (1.49)b | 4.72 (1.71)c | 5.51 (1.52)b |

| Distressed–satisfied | 3.96 (1.86)a | 5.38 (1.62)b | 4.51 (1.67)c | 5.34 (1.45)b |

| Time spent on writing (in seconds) | 368.35 (383.96)a | 326.59 (334.81)a | 337.20 (208.90)a | 300.64 (235.87)a |

| Number of words | 143.13 (89.72)a | 126.17 (76.29)a,b | 135.13 (77.64)b | 110.11 (74.42)b |

Means not sharing subscripts within rows are significantly different at the P < 0.05 based on Fisher’s least-significant difference post hoc paired comparisons.

A 2 × 2 ANOVA on the clarity scores revealed a significant main effect for both actor [F(1, 339) = 5.98, P = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.02] and nature of the act [F(1, 339) = 4.38, P = 0.032, ηp2 = 0.02] as well as a significant interaction [F(1, 339) = 4.95, P = 0.034, ηp2 = 0.02]. In the “self” conditions, participants had less clear memory of their unethical actions (M = 5.58, SD = 1.19) than of their ethical actions (M = 6.07, SD = 0.81) [F(1,169) = 10.17, P = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.06]. However, for those recalling someone else’s actions, clarity of memory did not differ depending on the ethicality of the act (Munethical = 5.54, SD = 1.11 vs. Methical = 5.55, SD = 1.13) [F(1,170) = 0.00, P = 0.98]. For thoughts and feelings scores, we found a main effect of actor [F(1, 339) = 11.69, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03] and a significant interaction [F(1, 339) = 5.99, P = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.02]. Similarly, on the thoughts and feelings measure, the difference between unethical (M = 5.49, SD = 0.98) and ethical acts (M = 5.93, SD = 0.84) was significant in the self conditions [F(1,169) = 9.86, P = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.06] but not when participants recalled someone else’s behavior (Munethical = 5.38, SD = 1.28 vs. Methical = 5.24, SD = 1.21) [F(1,170) = 0.54, P = 0.46].

Thus, even though people generally have a weaker memory of others’ actions than of their own, they remember others’ ethical and unethical acts similarly; however, people have less vivid memories of their own unethical experiences than of their own ethical ones.

Study 2: Actual Cheating and Its Subjective Memory.

Although the results of the first two experiments provide initial evidence for unethical amnesia, it is possible that people recalled different experiences across conditions. In study 2, a two-part laboratory study, we examine people’s subjective memories in a situation in which they had an opportunity to cheat to win more money.

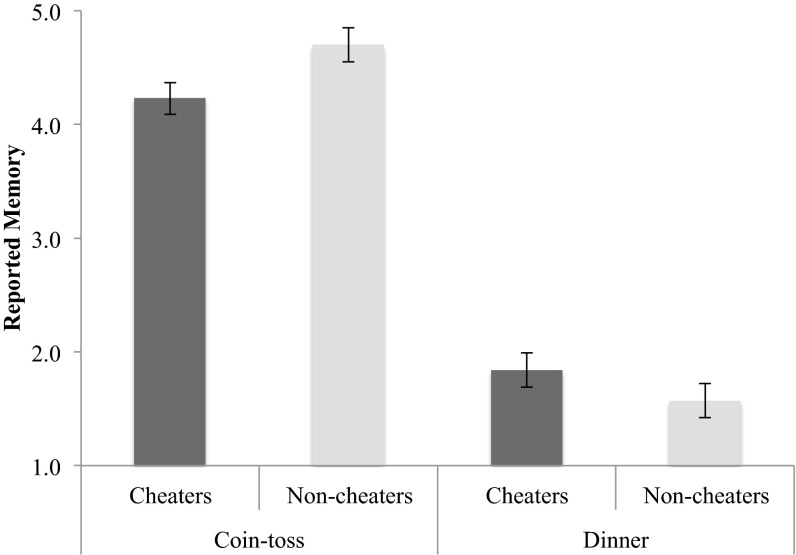

At time 1, participants played a coin-toss task in which, across 10 rounds, they could lie and earn more money. Two weeks later (n = 70), in a second laboratory session, we measured participants’ memory for the details of the coin-toss task and for another event that occurred on the same day (i.e., their dinner the night of the first laboratory session) to provide evidence for forgetting specifically related to cheating rather than to unrelated events.

To assess their memory of the coin-toss task and of their dinner, we used two different autobiographical memory measures presented to participants in random order to test the robustness of our effects: clarity (αcoin-toss task = 0.95; αdinner = 0.97) and thoughts and feelings (αcoin-toss task = 0.79; αdinner = 0.93) from the MCQ, and the Autobiographical Memory Questionnaire (AMQ) (14). The AMQ measures people’s autobiographical memory with eight items (e.g., “As I think about the coin-toss task/dinner that night, I can actually remember it”; αcoin-toss task = 0.88; αdinner = 0.97).

We examined differences in memory depending on the extent of cheating on the coin-toss task as well as differences in memory between those who cheated and those who did not. The amount of cheating on the coin-toss task significantly predicted the AMQ score (b = −1.05, SE = 0.40, P = 0.011), the clarity of one’s memory (b = −1.17, SE = 0.40, P = 0.004), and the thoughts and feelings score from the MCQ (b = −1.17, SE = 0.47, P = 0.015). Cheaters (i.e., those who cheated to some degree; 42.9% of participants) had worse memories of the coin-toss task (i.e., of their cheating) than did noncheaters (i.e., those who never cheated; 57.1% of participants). Their AMQ score was marginally lower (Mcheaters = 4.23, SD = 1.02 vs. Mnoncheaters = 4.70, SD = 1.19) [F(1, 68) = 3.04, P = 0.086, ηp2 = 0.04] (Fig. S1). Similarly, cheaters reported lower clarity of memory (Mcheaters = 4.60, SD = 1.08 vs. Mnoncheaters = 5.08, SD = 1.37) and recall of their thoughts and feelings (Mcheaters = 4.33, SD = 1.23 vs. Mnoncheaters = 4.89, SD = 1.34), both P = 0.081, ηp2 = 0.04.

Fig. S1.

Mean reported memory (AMQ) by cheating in study 2.

However, participants’ memory of their dinner the night of the first laboratory session was not affected by their behavior during the session. In fact, the extent of cheating was not related to any of the memory measures, Ps >0.88. Additionally, comparing cheaters with noncheaters revealed no significant differences between the two groups, Ps >0.22. Thus, people’s memory is impaired for unethical actions but not for ethical behavior or for neutral events.

Study 3: Random Assignment to Unethical Behavior.

In studies 1 and 2, we had no control over people’s actions; thus, in study 3, we randomly assigned participants to read a story describing either ethical or unethical behavior. A sample of adults participated in a two-part online study. In part 1, they read one of two detailed stories about cheating on an examination or not cheating (unethical or ethical version) and were asked either to take a first-person perspective and put themselves in the position of the main character or to read it from a third-person perspective. Four days later, the participants (n = 194) completed the MCQ measure (clarity, α = 0.94; thoughts and feelings, α = 0.95) and the AMQ measure (α = 0.96).

A MANOVA using participants’ ratings for the all measures (AMQ, clarity, thoughts and feelings) as dependent variables and the actor and nature of the act as between-subjects factors showed a significant interaction effect [F(3, 188) = 3.51, P = 0.016, ηp2 = 0.05].

The 2 × 2 (actor × nature of the act) ANOVA on the AMQ revealed a significant interaction effect [F(1, 190) = 10.37, P = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.05]. When taking a first-person perspective, participants remembered the story less well when it was about cheating (M = 1.20, SD = 0.42) than when it was not (M = 1.92, SD = 1.33) [F(1, 96) = 12.57, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12]. However, for participants in the third-person condition, there was no difference in memory between the ethical (M = 1.42, SD = 0.87) and unethical stories (M = 1.64, SD = 1.19) [F(1, 94) = 1.13, P = 0.29] (Fig. S2).

Fig. S2.

Mean reported memory (AMQ) by condition in study 3.

Similarly, the 2 × 2 (actor × nature of the act) ANOVA on the clarity factor revealed a significant interaction [F(1, 190) = 4.42, P = 0.037, ηp2 = 0.02]. Those participants recalling cheating reported less clear memory of the story (M = 1.54, SD = 0.82) than did those remembering acting ethically on the examination (M = 2.07, SD = 1.42) [F(1, 96) = 5.01, P = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.05]. However, there was no difference between the memory of ethical (M = 1.56, SD = 0.93) and unethical (M = 1.68, SD = 0.97) acts in the third-person perspective condition [F(1, 94) = 0.35, P = 0.56]. The same interaction effect emerged on the thoughts and feelings measure [F(1, 190) = 4.12, P = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.02]. Participants in the self-unethical condition had a less clear recall of thoughts and feelings (M = 1.72, SD = 1.10) than did participants in the self-ethical condition (M = 2.35, SD = 1.73) [F(1, 96) = 4.60, P = 0.035, ηp2 = 0.05]. However, there was no difference in the memory of ethical (M = 1.82, SD = 1.30) and unethical behavior (M = 2.01, SD = 1.41) in the third-person perspective condition [F(1, 94) = 0.46, P = 0.50].

These results show that people have less clear memory of their own unethical experiences than of their ethical experiences. However, when they take a third-person perspective (which is less threatening to their moral self-image), the type of behavior does not impact their memory.

Study 4: The Role of Time on Subjective Memory of Unethical Acts.

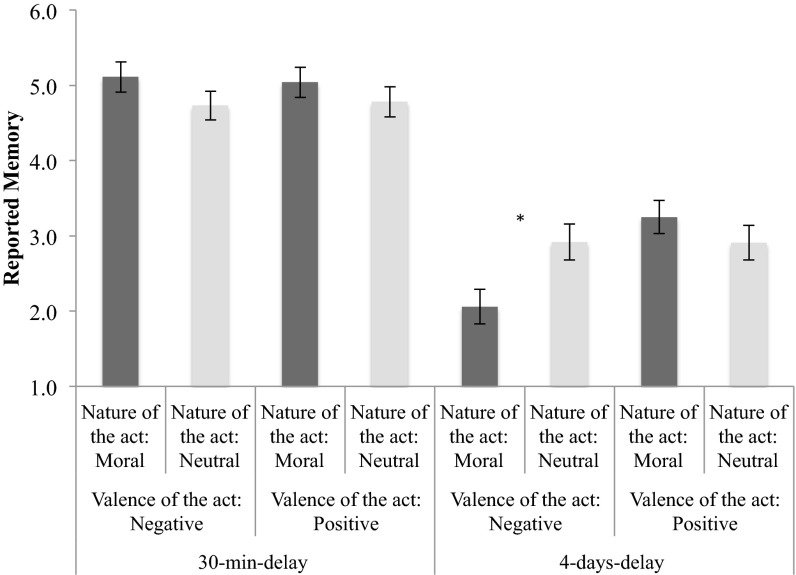

In study 4, participants read a story describing different behaviors and then answered questions about their memory of the story after either 30 min or 4 d. We manipulated both the nature of the act (moral vs. not moral) and its valence (positive vs. negative) to examine further the differences between unethical and negative experiences. We varied the time at which we asked participants about their memory of the event to examine whether people immediately distance themselves from the experience or whether such memory fading happens over time. Thus, the study used a 2 × 2 × 2 (nature of the act: moral vs. neutral × valence of the act: positive vs. negative × delay in assessing memory: 30 min vs. 4 d) design.

Participants in all conditions first read a story and then completed a filler task for 30 min. Those in the 30-min-delay condition (n = 148) then completed the AMQ measure. Those in the 4-d-delay condition (n = 109) were contacted 4 d later and answered the same questions about their memory of the story they had read in part 1.

We ran a 2 × 2 × 2 (nature of the act × valence of the act × delay) ANOVA on the AMQ scores (α = 0.88). As predicted, we found a significant three-way interaction [F(1, 249) = 4.88, P = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.02], which is depicted in Fig. 1. Among those who responded to the memory questions 30 min after reading the story, the nature of the act had only a marginal main effect, such that participants recalled the moral version more clearly than the neutral one [F(1, 144) = 3.60, P = 0.060, ηp2 = 0.02].

Fig. 1.

Mean reported memory (AMQ) by condition in study 4. *P ≤ 0.05.

However, among those who answered the memory questions 4 d later, there was a main effect of valence of the act, such that the memory score was lower for negative than for positive acts [F(1, 105) = 4.90, P = 0.029, ηp2 = 0.05]. Importantly, the interaction of the nature of the act × its valence was significant [F(1, 105) = 5.13, P = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.05]. In the moral-act conditions, participants who read that they had cheated (i.e., moral nature of the act/negative valence of the act condition) indicated they had a less clear memory (M = 2.06, SD = 1.34) than those who did not cheat (M = 3.25, SD = 1.38) [F(1, 55) = 13.75, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.20]. However, in the neutral-act conditions, there was no difference in memory depending on the valence of the act (Mnegative = 2.93, SD = 1.29 vs. Mpositive = 2.91, SD = 1.29) [F(1, 50) = 0.001, P = 0.98].

Together, these results show that, as we predicted, people’s subjective memory of ethical or unethical actions does not differ at the time when the event occurs. Over time, however, the memory of unethical actions becomes less clear.

Study 5: Objective Memory of One’s Unethical Acts.

In our previous studies we used subjective memory measures. In study 5, we used an objective measure. In a two-part online study, we randomly assigned participants to read a story about either ethical or unethical actions (as in studies 3 and 4). We asked participants (n = 88) to take a first-person perspective and put themselves in the position of the main character. One week later, they answered questions to evaluate their memory of the story by indicating whether each of 18 statements containing details of the original story was part of the story they had read or not. This objective memory score was, on average, lower for those who read in the story that they had cheated (M = 14.37, SD = 2.51) than for those who read that they had behaved honestly (M = 15.23, SD = 1.38), t(87) = 1.99, P = 0.049, d = 0.43.

Study 6: Unethical Amnesia Results from the Dissonance Experienced When Cheating.

Consistent with prior research, we suggested that when people behave unethically they experience greater dissonance and discomfort. This dissonance, we argued, triggers unethical amnesia. Because of this experienced dissonance people avoid thinking about their past unethical behavior often, because this information is threatening to their self-image. To provide evidence for the role of dissonance in creating unethical amnesia after unethical actions, we conducted a two-part online study in which we measured participants’ level of psychological discomfort and their moral self-concept after having an opportunity to cheat and their memory of this task 2 days later.

At time 1, participants played a die-throwing game: They had to throw a virtual six-sided die 20 times to earn points (which would be translated to real dollars and added to their final payment). Before each throw, participants had to choose the relevant side for that round: the visible side of the die (“U”) or the invisible one, facing down (“D”).

We randomly assigned participants to one of two conditions: likely-cheating vs. no-cheating. In the likely-cheating condition, participants had to choose mentally between U and D before every throw, and after each throw, they indicated the side they had chosen before the throw. In the no-cheating condition, participants were also asked to choose mentally between U and D before every throw, but they had to report their choice before throwing the virtual die. Thus, the likely-cheating condition tempted participants to cheat, whereas the no-cheating condition did not allow cheating.

Afterward, participants completed a measure of moral self-concept by indicating how they felt on items such as moral and trustworthy (α = 0.96) and a measure of dissonance by indicating how they felt on items such as uncomfortable and ashamed (α = 0.97).

Two days later, at time 2, participants (n = 279) answered questions about their memory of the die-throwing task on the AMQ measure (α = 0.89) and then answered questions about their current moral self-concept (α = 0.96) and their current level of psychological discomfort (α = 0.98).

As expected, at time 1, participants in the likely-cheating condition reported greater discomfort (M = 2.85, SD = 1.75) and lower scores on the moral self-concept (M = 3.80, SD = 1.77) than participants in the no-cheating condition (Mdiscomfort = 2.37, SD = 1.66 and Mmoral self-concept = 4.35, SD = 1.76) [t(277) = 2.33, P = 0.021, d = 0.28 and t(277) = −2.57, P = 0.011, d = 0.31, respectively]. However, these differences disappeared at time 2: Participants in the likely-cheating condition reported feeling the same level of discomfort (M = 2.06, SD = 1.46) and had similar scores on the moral self-concept (M = 4.98, SD = 1.35) as participants in the no-cheating condition (Mdiscomfort = 2.24, SD = 1.56 and Mmoral self-concept = 5.02, SD = 1.38), both Ps >0.33. Importantly, although psychological discomfort was significantly lower at time 2 than at time 1 for participants in the likely-cheating condition [F(1, 133) = 34.31, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.21], it was not different across time for participants in the no-cheating condition [F(1, 144) = 1.32, P = 0.25.

Providing evidence for unethical amnesia, participants in the likely-cheating condition recalled the die-throwing task less precisely (M = 4.92, SD = 1.16) than those in the no-cheating condition (M = 5.54, SD = 1.03) [t(277) = 4.76, P < 0.001, d = 0.57].

Importantly, as we predicted, the dissonance that participants experienced at time 1 and their perceived moral self-concept mediated the relationship between our manipulation of cheating and memory of the task at time 2. Based on bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples, we found that both psychological discomfort [95% bootstrapped confidence interval (CI): −0.14, −0.01] and perceived moral self-concept (95% bootstrapped CI: −0.13, −0.007) exerted significant indirect effects. Thus, the relationship between initial unethical behavior and greater unethical amnesia later on is mediated by the dissonance people experience after cheating and the negative impact such dishonesty has on their moral self-concept. Indeed, the higher the level of distress participants experienced at time 1 and the lower their self-reported moral self-image, the greater was the unethical amnesia reported at time 2.

These results show that the discomfort people experienced because of their unethical behavior is alleviated over time, and the more dissonance they experience after cheating, the fuzzier the memory of their unethical actions become.

Studies 7a and 7b: Unethical Amnesia Leads to Greater Subsequent Dishonesty.

We suggested that unethical amnesia provides one explanation for why people cheat persistently over time. We tested this hypothesis directly in our last two experiments. Study 7a was a two-part online study. At time 1, participants (n = 220) played the same die-throwing game as in study 6, but this time we did not include survey measures. At time 2, 3 days later, participants answered questions evaluating their memory of the die-throwing task on the AMQ measure (α = 0.84).

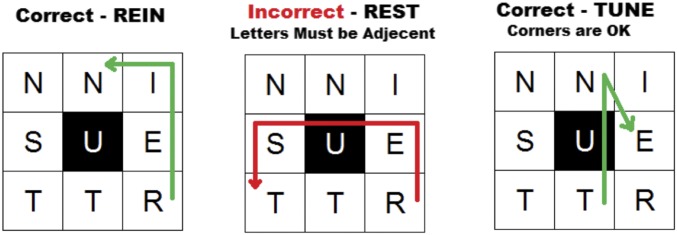

Next, we gave participants an opportunity to cheat: In particular, they engaged in a task in which they could misreport their performance for extra money. The task involved unscrambling 10 word jumbles; they would receive a $1 bonus for every jumble they reported they had solved correctly. Participants indicated which word jumbles they unscrambled successfully without being asked to write out the unscrambled words. The instructions informed them that the word jumbles would have to be solved in the order in which they appeared on the screen. However, the third word jumble could be unscrambled only to spell the obscure word “taguan.” No one had unscrambled this word successfully in a pilot study (see SI Study 7a), so it was unlikely that participants acting honestly would report having solved this jumble. We used the frequency with which participants reported having solved the third word jumble as the measure of cheating at time 2.

As we expected, participants in the likely-cheating condition recalled the die-throwing task less precisely (M = 2.17, SD = 0.82) than those in the no-cheating condition (M = 2.51, SD = 0.96) [t(218) = −2.80, P = 0.006, d = 0.38]. They also were more likely to cheat at time 2 [χ2(n = 220) = 4.58, P = 0.032, Cramer’s V = 0.14]; in fact, 81% (84 of 104) of the participants in the likely-cheating condition cheated at time 2 by reporting they had solved the third word jumble, whereas only 68% (79 of 116) of the participants in the no-cheating condition cheated on this second task measuring dishonesty.

Importantly, and as is consistent with our predictions, unethical amnesia mediated the effect of our manipulation on cheating on the word jumble task at time 2. In fact, bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples indicated that the 95% bootstrapped CI excluded zero (CI: 0.029, 0.477), providing evidence for a significant indirect effect. Thus, cheating causes unethical amnesia later on, and such impairment in people’s memory of their unethical actions drives further unethical behavior on subsequent tasks.

To provide a conceptual replication of these findings, we conducted another study using a different sample of participants and a different cheating task at time 2. Study 7b also was a two-part online study. At time 1, a sample of adults played the die-throwing game used in study 7a. Three days later, at time 2, participants (n = 258) answered questions evaluating their memory of the die-throwing task on the AMQ measure.

Next, we gave participants an opportunity to cheat on a task called the “Boggle task.” In this task, participants had to identify as many four-letter words as could be constructed from adjacent letters (including corners) in a three-by-three letter grid within a 2-min timeframe (Fig. S3). Participants were offered a monetary bonus for each correct word. Once the participants finished the Boggle task, or when the time expired, we asked them how many words they had identified correctly. Following a page break, we then presented participants with the original letter matrix and asked them to type in the words they identified so that we could pay them their correct bonus. Cheating, in this case, occurs every time people over-report their performance on the Boggle task (i.e., the number of words participants typed in - after the page break - is higher than the number they reported they got correct when they first saw the nine-letter box).

Fig. S3.

The Boggle task used in study 7b: a copy of the screen participants saw in the instruction phase.

As predicted, participants in the likely-cheating condition recalled the die-throwing task less precisely (M = 2.59, SD = 1.08) than those in the no-cheating condition (M = 2.97, SD = 1.22) [t(256) = −2.66, P = 0.008, d = 0.33]. They also were more likely to cheat at time 2 [χ2(n = 258) = 10.48, P = 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.20] providing further evidence for the consequences of unethical amnesia; in fact, 78% (96 of 123) of the participants in the likely-cheating condition cheated at time 2 on the Boggle task, a percentage that was higher than observed in the no-cheating condition, in which 59% (80 of 135) of the participants cheated.

Next, we examined whether unethical amnesia mediated the effect of our manipulation of the opportunity for dishonesty at time 1 on cheating on the Boggle task at time 2. As expected, bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples indicated that the 95% bootstrapped CI excluded zero (CI: 0.087, 0.515), providing evidence for a significant indirect effect. These results replicate the findings of study 7a and suggest that unethical amnesia explains persistent cheating over time.

Discussion

We encounter moral situations frequently (15). Indeed, morality is “a uniquely human characteristic—one that sets us apart from other species” (16). Because morality is such a fundamental part of human existence, people have a strong incentive to view themselves and be viewed by others as moral individuals. However, when encountering an opportunity to act dishonestly and benefit from it, people often choose to diverge from their moral compass and cheat. Across nine studies using diverse sample populations (undergraduate students and online panels of adults), we examine one possible reason why, despite the discomfort they experience after behaving unethically, people engage in similar ethically questionable behaviors over time. We find evidence that people experience unethical amnesia, forgetting of the details of their unethical actions over time, even when the transgressions are minimal and hypothetical. We document that acting unethically produces changes in memory, such that the memories of unethical actions are less clear and vivid over time than the memories of other type of actions. After they behave unethically, individuals’ memories of their actions become more obfuscated over time because of the psychological distress and discomfort caused by such misdeeds. This unethical amnesia and the alleviation of such dissonance over time are followed by more dishonesty subsequently in the future.

Our studies contribute to the literature on memory and motivated forgetting in four important ways. First, we examine memories of unethical deeds to understand the extent to which people think about such actions. Prior research has demonstrated that moral disengagement and motivated forgetting of ethical standards are common consequences of dishonesty. The empirical studies on motivated forgetting often focus on the memory of a specific threat-related stimulus rather than on the clarity and vividness of the memory of such incidents. In this paper, we examine the clarity, vividness, and level of details of people’s memories of their unethical acts. In so doing, we broaden the scope of existing research by shifting attention from a specific threat-related stimulus to the clarity of the memories of such experiences.

Second, most studies of emotional memory have examined short-lived emotional reactions to specific stimuli and have not considered the longer-term effects. Autobiographical memories can help us document changes in the memory of an experience over time. We thus contribute to the research on memory biases and distortions by demonstrating that one’s unethical acts lead to gradual decrements of the memory of the situation and the details associated with it. Specifically, our findings show that at the time of an ethical or unethical event, people’s subjective experiences of it do not differ from a memory perspective. Over time, however, people’s memory for unethical acts becomes less accessible, vivid, and clear. Presumably this obfuscation occurs because the memory of unethical acts is unwelcome, and thus people are less likely to think about them. Research has found that memories that are not revived are less likely to be remembered later (17) or are remembered less vividly (18); motivated retrieval-suppression mechanisms (10) may increase the chances that unwelcome memories are not revived.

Third, knowing that individuals self-enhance and forget memories is not sufficient; we need to know why this forgetting occurs and what implications it has on people’s behavior. Our results indicate that unethical amnesia is driven by the desire to lower one’s distress that comes from acting unethically and to maintain a positive self-image as a moral individual. This may be an adaptive, defensive behavior, because people are less likely to retrieve memories that threaten their self-concept and induce a negative mood. As a result, because unwanted memories of their dishonest behavior are obfuscated, people are more likely to act unethically repeatedly over time.

Fourth, we find that remembering personal experiences is modulated by the relevance of the events to one’s self-image. People’s self-images are grounded in autobiographical memories. We did not find a difference between the memory of ethical and unethical actions performed by someone else, i.e., in the third-party accounts. Given the importance of morality in person perception (16), remembering one’s unethical actions is distinct from the memory of other unpleasant situations because of morality’s critical role in one’s self-view. Memories of one’s unethical behavior fade faster over time because of the greater motivated forgetting relative to other events. Because some remembered memories are more central to self-definition than others, distinguishing different types of experiences is critical in explaining the effects of the valence of events on the clarity and vividness of one’s memory.

Our work also contributes to the literature on moral psychology and behavioral ethics. Research has shown the role of psychological processes in predicting individuals’ moral and immoral actions. However, the psychological consequences of dishonest behavior, and particularly its long-term effects, have been understudied. In this paper, we highlight an important consequence of dishonesty: obfuscation of one’s memory over time because of the psychological distress and discomfort created by unethical actions. We find that after they engage in unethical behavior, individuals’ memories of their unethical actions are less clear than their memories of ethical actions, whether negative, positive, or neutral. These results are particularly important because unethical amnesia can explain why ordinary, good people repeatedly engage in unethical behavior and also how they distance themselves from such behavior over time. Our findings further demonstrate the critical role of moral self-concept as we construct and reconstruct experiences to maintain our moral self-image intact regardless of our behavior.

Materials and Methods

Here we describe the sample populations we recruited in our nine studies. For additional methodological detail, full results, and tables, refer to the Supporting Information. Data are available from the corresponding author. We obtained informed consent from all participants, and the Institutional Review Board of Harvard University reviewed and approved all materials and procedures in our studies.

Study 1a.

In study 1a, 400 individuals (234 men; Mage = 31.7 y, SD = 9.1 y) located in the United States and recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk participated in a two-part online study for $1.

Study 1b.

In study 1b, 352 individuals (182 men; Mage = 29.7 y, SD = 9.1 y) located in the United States and recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk participated in a two-part online study for $1.

Study 2.

In study 2, 80 students (42 men, Mage = 22.1 y, SD = 3.7 y) at a university in the United States participated in the study for $15 and the opportunity to earn an additional $10. All participants were recruited to complete a two-part laboratory study and were instructed that they could complete the second part in exactly 2 wk for an additional payment of $20. Seventy students (36 men, Mage = 22.5, SD = 3.9) returned 2 wk later to complete the follow-up survey in the laboratory (88% response rate).

Study 3.

In study 3, 222 individuals located in the United States and recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk participated in a two-part online study for $1 with an opportunity to complete the second part in 4 d for an additional $1. Four days later, 194 participants (98 men, Mage = 34.8 y, SD = 12.7 y) completed part 2 of the study (80% response rate).

Study 4.

In study 4, 300 individuals located in the United States and recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk participated in a two-part online study for $1 with an opportunity to complete the second part in 4 d for an additional $1. In 30 min, 148 participants completed the survey with study variables of interest. Four days later, 109 participants completed part 2 of the study with study variables of interest (72% response rate). Our final sample size was 257 participants (140 men; Mage = 32.1 y, SD = 8.5 y).

Study 5.

In study 5, 127 students at a university in the United States participated in a two-part online study for a $10 Amazon gift card. Participants were asked to complete the second part in exactly 1 wk. To make sure most participants took both parts of the study, participants were informed that they would receive payment only after completing both parts of the study. One week later, 88 students (27 men, Mage = 20.2 y, SD = 1.9 y) completed the follow-up online survey (70% response rate).

Study 6.

In study 6, 301 students at a university in the United States participated in a two-part online study for a $10 Amazon gift card and the opportunity to earn an additional bonus based on their performance throughout the study (up to $20, also to be paid through Amazon gift cards). Participants were asked to complete the second part of the study 2 d later. To make sure most participants took both parts of the study, participants were informed that they would receive payment only after completing both parts of the study. Two days later, 279 students (145 men; Mage = 21.8 y, SD = 2.89 y) completed the follow-up online survey (93% response rate).

Study 7a.

In study 7a, 269 students at a university in the United States participated in a two-part online study for a $10 Amazon gift card and the opportunity to earn an additional bonus based on their performance throughout the study (up to $30, also to be paid through Amazon gift cards). Participants were asked to complete the second part of the study 3 d later. To make sure most participants took both parts of the study, participants were informed that they would receive payment only after completing both parts of the study. Three days later, 220 students (148 men; Mage = 20.5 y, SD = 1.39 y) completed the follow-up online survey (82% response rate).

Study 7b.

In study 7b, 283 individuals located in the United States and recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk participated in a two-part online study for $3 and the opportunity to earn an additional bonus of $20 depending on their performance throughout the study. Participants were asked to complete the second part of the study 3 d later. To make sure most participants took both parts of the study, participants were informed that they would receive payment only after completing both parts of the study. Three days later, 258 participants (127 men; Mage = 37.25 y, SD = 10.31 y) completed the follow-up online survey (91% response rate).

SI Study 1a

Method.

Study 1a had five between-participants conditions: unethical behavior, ethical behavior, positive experience, negative experience, and neutral experience. Participants were randomly assigned to one of these five conditions. We asked participants to recall a certain event they had experienced personally in the past and to write about it in detail for a few minutes.

Participants in the unethical condition were asked to describe one unethical thing they had done that made them feel guilt, regret, or shame. They were told that other people engaging in this type of recall task frequently write about instances in which they acted selfishly at the expense of someone else, took advantage of a situation and were dishonest, or were untruthful or disloyal. They were asked to describe the situation and any thoughts and feelings they remembered from the experience in as much detail as possible so that a person reading their entry would understand the situation, what happened, and how they felt. In the other conditions, the instructions were similar, but we asked participants to write about a different type of experience: (i) one ethical thing they had done that made them feel happy, proud, or pure (ethical behavior condition); (ii) a negative event that happened to them that made them feel disappointed, sad, anxious, or embarrassed (negative experience condition); (iii) a positive event that happened to them that made them feel happy, excited, or satisfied (positive experience condition); or (iv) how they usually spend their evenings (control condition). As in the unethical condition, we provided some examples in each condition.

Immediately after this writing task, participants completed a memory measure. We adapted a few items from the MCQ (13). The MCQ assesses various qualitative characteristics of one’s memory (e.g., the spatial arrangement of objects, how one felt, characteristics such as visual clarity). The clarity dimension is a general vividness factor depending on perceptual and sensory information, and the thoughts and feelings factor relies on semantic and sensory information. Hence, clarity and thoughts and feelings rely on perceptual, sensory, and semantic information. In addition, the MCQ measures spatiotemporal features. Prior work has found that perceptual, sensory, and semantic information (i.e., clarity, sensory detail, and thoughts and feelings) is better recalled for emotional memories than for neutral ones, but emotional memories do not differ from neutral ones on memory measures related to spatial context and time (19). Because people recalled their own past experiences in studies 1a and 1b, we used the full version of the MCQ. Across all our studies, we focus on the clarity and thoughts and feelings dimensions; however, the results for the other dimensions for studies 1a and 1b are presented in Tables S1 and S2.

For clarity of memory, participants were asked to rate four items (α = 0.86) using seven-point scales: (i) Overall, I remember this event: [hardly (1) to very well (7)]; (ii) My memory of this event task is [dim (1) to sharp/clear (7)]; (iii) The overall vividness of the event is [vague (1) to very vivid (7)]; and (iv) My memory of the event is [sketchy (1) to highly detailed (7)]. We measured thoughts and feelings with two items (α = 0.64) on a seven-point scale: (i) I remember how I felt at the time I just recalled [not at all (1) to clearly (7)]; (ii) I remember what I thought at the time of the event I just recalled [not at all (1) to clearly (7)]. Next, participants were asked to identify the type of event and then specify when the event happened on a scale of 1 (just today) to 9 (more than a year ago). They also were asked to report how they felt while describing the event from memory on a seven-point scale: bad–good, sad–happy, tense–relaxed, negative–positive, uncomfortable–comfortable, distressed–satisfied. Finally, participants completed the positive (α = 0.90) and negative (α = 0.93) affect schedule using a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Results.

Table S1 reports the mean and SD of the main variables assessed in this study by condition.

We used an online survey tool that allowed us to record how much time each participant spent on the writing task. Thus, as a manipulation check, we compared the time each participant spent on the writing task as a proxy for their attention and engagement and found no significant difference across conditions [F(4, 395) = 1.51, P = 0.20].

MCQ responses.

A MANOVA using participants’ ratings for all measures (clarity, thoughts and feelings, bad–good, sad–happy, tense–relaxed, negative–positive, uncomfortable–comfortable, and distressed–satisfied) as dependent variables and condition as a between-participants factor showed a significance between all conditions on our dependent variables [F(8, 391) = 12.82, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.21]. Results of univariate tests with the writing condition as a between-participants factor revealed a significant difference among conditions for the clarity scores [F(4, 395) = 6.14, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06] and for the thoughts and feelings scores [F(4, 395) = 11.08, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10].

Next, we ran a series of analyses to compare the unethical condition with the other conditions; the results are summarized in Table S1. Overall, the pairwise comparisons indicate that the unethical condition had a significantly lower value than each of the other conditions. Of particular interest is the comparison between the unethical condition and the negative condition: Memory was significantly lower in the unethical condition than in the negative condition for both clarity (Munethical = 5.38 vs. Mnegative = 5.90) and thoughts and feelings (Munethical = 5.07 vs. Mnegative = 5.61) scores.

Emotions.

For self-reported emotions, the unethical and negative conditions did not differ on any of the items (bad–good, sad–happy, tense–relaxed, negative–positive, uncomfortable–comfortable, distressed–satisfied), nor did the conditions differ in negative and positive affect (all Fs <1). This finding provides evidence that the essays did not differ in terms of the intensity of the emotions the participants felt during the memory recollection. See Table S1 for the differences between all conditions on each measure.

Timing of the event described.

Importantly, the time the event occurred was not significantly different between the unethical and negative conditions (Munethical = 7.86 vs. Mnegative = 7.73; P = 0.62) (Table S1).

Word count.

Writing about unethical events, especially when the self is involved, might be difficult; alternatively, doing so may have a positive impact, because writing about traumatic events can help one overcome them. Thus, we examined the number of words each participant wrote across conditions. We found a significant effect of condition on the number of words written [F(4, 395) = 2.51, P = 0.042]. Pairwise comparisons showed that participants in the negative event condition wrote more words than participants in either the positive event or the unethical event condition (P = 0.013 and P = 0.020, respectively). We did not find significant differences in the comparisons between other conditions. Given the significant difference noted above, we ran all the analyses while controlling for the number of words in the essays participants wrote. Importantly, all our results remain the same in direction and significance levels.

SI Study 1b

Method.

Participants were randomly assigned to a 2 × 2 (actor: self vs. someone else × nature of the act: unethical vs. ethical) between-participants design. The instructions for the ethical and unethical recall task were identical to those for study 1a. In the self conditions, participants were asked to recall and describe their own unethical or ethical actions. In the someone-else conditions, they were asked to recall and describe the unethical or ethical behavior of another person.

Afterward, all participants were asked to rate their memory of the experience they had written about using seven-point scales on the MCQ items (clarity α = 0.89, thoughts and feelings α = 0.61). Finally, participants were asked to report how they felt, using all the items from study 1a.

Results.

Table S2 reports the mean and SD of the main variables assessed in the study by condition.

We compared the time each participant spent on the writing task as a proxy for their attention and engagement and found no significant difference across conditions [F(3, 339) = 0.74, P = 0.53].

MCQ responses.

A MANOVA using participants’ ratings for all measures (clarity, thoughts and feelings, bad–good, sad–happy, tense–relaxed, negative–positive, uncomfortable–comfortable, distressed–satisfied) as dependent variables and the actor and the nature of the act as between-participants factors showed a significant main effect for both actor [F(8, 332) = 2.71, P = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.06] and nature of the act [F(8, 332) = 11.46, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.22]. The analysis also yielded a significant interaction effect [F(8, 332) = 1.96, P = 0.050, ηp2 = 0.05]. A 2 × 2 ANOVA on the clarity scores revealed a significant main effect for both actor [F(1, 339) = 5.98, P = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.02] and nature of the act [F(1, 339) = 4.38, P = 0.032, ηp2 = 0.02]. The analysis also yielded a significant interaction effect [F(1, 339) = 4.95, P = 0.034, ηp2 = 0.02]. For thoughts and feelings scores, we found a main effect of actor [F(1, 339) = 11.69, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03] and a significant interaction effect [F(1, 339) = 5.99, P = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.02].

To interpret the interaction, we conducted multiple planned comparisons. For clarity, the results showed that within the self conditions, participants in the unethical condition had less clear memory (M = 5.58, SD = 1.19) than participants in the ethical condition (M = 6.07, SD = 0.81) [F(1,169) = 10.17, P = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.06]. However, for those recalling someone else’s actions, clarity of memory did not differ significantly between unethical (M = 5.54, SD = 1.11) and ethical (M = 5.55, SD = 1.13) acts [F(1,170) = 0.00, P = 0.98]. We also note there were no differences between the clarity of the memory of one’s own unethical actions (M = 5.58, SD = 1.19) and the unethical actions of others (M = 5.54, SD = 1.11) [F(1,168) = 0.04, P = 0.84]. We also compared people’s memory of their own ethical actions (M = 6.07, SD = 0.81) and those of others (M = 5.55, SD = 1.13) and found that they differed significantly [F(1,171) = 12.54, P = 0.001]. This pattern of results indicates a generally weaker memory of others’ actions than of one’s own actions.

The findings for thoughts and feelings are similar to those of clarity scores. In the self conditions, we find a significant difference between unethical (M = 5.49, SD = 0.98) and ethical acts (M = 5.93, SD = 0.84) [F(1,169) = 9.86, P = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.06] but no significance difference for others (M = 5.38, SD = 1.28 vs. M = 5.24, SD = 1.21) [F(1,170) = 0.54, P = 0.46]. Similarly, on the thoughts and feelings scores, we found no differences between one’s own unethical actions (M = 5.49, SD = 0.98) and the unethical actions of others (M = 5.38, SD = 1.28) [F(1,168) = 0.43, P = 0.51]. There was a significant difference between one’s own ethical actions (M = 5.93, SD = 0.84) and those of others (M = 5.24, SD = 1.21) [F(1,171) = 19.10, P < 0.001]. Once again, we attribute this significant difference to a weaker memory for others’ actions than for one’s own.

Word count.

As in study 1a, we examined the number of words each participant wrote. We ran a 2 × 2 (actor: self vs. someone else × nature of the act: unethical vs. ethical) between-participants ANOVA. The analysis revealed no main effect for actor [F(1,339) = 1.98, P = 0.17] nor a significant interaction [F(1,339) = 0.21, P = 0.65]; there was a significant effect for nature of the act (Munethical = 139.12 vs. Methical = 118.27) [F(1,3339) = 6.01, P = 0.015]. Given the significant difference, we ran all the analyses while controlling for the number of words in the essays the participants wrote. Our results were similar in both their nature and significance.

SI Study 2

Method.

Study 2 was a two-part study. In the first laboratory session, participants were informed that they would complete a prediction task in which they would be asked to predict the outcome of a virtual coin toss. Participants first indicated whether to predict heads or tails. After recording their prediction, they flipped a coin virtually and then reported whether their prediction matched the actual outcome. They were told that they would earn $1 if they had guessed correctly. Participants were further instructed that they would complete 10 rounds of the coin flip task. Before proceeding to the payment rounds, they were asked to complete a practice round in which they did not earn money. Participants were directed to an ostensibly independent website that allowed them to flip a coin virtually. This website offered a true random coin flip, but, unbeknownst to the participants, we were able to record the outcome of each virtual coin toss and link it to participants’ identification numbers used in the laboratory session. Importantly, the website was designed so that participants’ unique identification numbers did not appear on the website; therefore, participants believed that this was an independent website. Thus, we were able to identify whether participants cheated on any of the 10 rounds. To increase the sense of anonymity, we placed an envelope containing 10 $1 bills on each desk where participants sat throughout the study and asked participants at the end of each round to take $1 if their prediction was correct. If their prediction was incorrect, they would not earn any money and were asked to proceed to the next round. In each round, after participants flipped the virtual coin, we reminded them of their prediction before they indicated whether the outcome matched the prediction or not. We did not instruct participants that there would be a memory test in the second part of the study. At the end, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

In the second laboratory session, exactly 2 wk later, participants were told that they would be asked to answer a few questions about the task they had completed in the first laboratory session. They further learned that the goal of the study was to investigate how people remember and reflect on events from the past. Next, they were reminded that 2 wk earlier, they had come to the laboratory and completed a coin-toss task. They then were asked to answer questions about their memory of the coin-toss task. To test the robustness of our effects, all participants completed two different autobiographical memory measures in reference to the coin-toss task in random order. We used the same measures to assess participants’ memory for the details of another event that occurred on the day of the first laboratory sessions: their dinner on the night of that session.

We used the AMQ (14) with eight items (αcoin-toss task = 0.88; αdinner = 0.97) assessed on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = as clearly as if it were happening right now). Sample items include: “As I think about the coin-toss task, I can actually remember it” and “As I remember the coin-toss task, I can feel now the emotions that I felt then.” All participants also completed the clarity (αcoin-toss task = 0.95; αdinner = 0.97) and thoughts and feelings (αcoin-toss task = 0.79; αdinner = 0.93) items from the MCQ in reference to the coin-toss task.

Results.

Out of 800 total rounds (10 rounds for 80 participants), ∼52% (419 rounds) of the coin-toss outcomes did not match the participants’ predictions, thus presenting an opportunity for cheating. To account for the extent to which participants could have cheated, we computed a cheating ratio, dividing the number of over-reports the participant made by the number of over-reports the participant could have made. A value of zero on the cheating ratio means no cheating, whereas a value of 1 means cheating to the fullest degree possible. The average cheating was 0.23 (SD = 0.33) with a minimum of zero (56.3%) and maximum of 1 (8.7%). Ten participants (five of whom never lied and five of whom lied to some degree) did not return for the second laboratory session. Thus, we were left with 70 participants for the analyses.

Coin toss MCQ and AMQ responses.

Results of regression analyses revealed that the amount of cheating significantly predicted the AMQ score (b = −1.05, SE = 0.40, P = 0.011), the clarity of memory score from the MCQ (b = −1.17, SE = 0.40, P = 0.004), and the thoughts and feelings score from the MCQ (b = −1.17, SE = 0.47, P = 0.015). Also, we compared cheaters (i.e., those who cheated on at least one round; 42.9% of participants) with noncheaters (i.e., those who never cheated; 57.1% of participants). The average score of cheaters on the AMQ was marginally lower (M = 4.23, SD = 1.02) than that of noncheaters (M = 4.70, SD = 1.19) [F(1, 68) = 3.04, P = 0.086, ηp2 = 0.04] (Fig. S1). Similarly, cheaters reported lower clarity of memory (Mcheaters = 4.60, SD = 1.08 vs. Mnoncheaters = 5.08, SD = 1.37) and recall of their thoughts and feelings (Mcheaters = 4.33, SD = 1.23 vs. Mnoncheaters = 4.89, SD = 1.34), both P = 0.081, ηp2 = 0.04.

Dinner MCQ and AMQ responses.

Next, we turned to participants’ memories of their dinner on the night of the first laboratory session. Results of regression analyses revealed that the number of rounds on which each participant cheated did not predict any of the self-reported memory measures of their dinner, Ps >0.88. Additionally, comparing cheaters with noncheaters found no significant differences between the two groups on any of the measures, Ps >0.22.

SI Study 3

Method.

Study 3 was a two-part online study. In part 1, participants were randomly assigned to a 2 × 2 (actor: self vs. third-person × nature of act: unethical vs. ethical) between-participants design. Participants were asked to read a story (see SI Scenario Pair A, below). According to the condition to which they had been randomly assigned, participants read one of two short stories of about 250 words. Participants in the self-conditions took a first-person perspective and were asked to put themselves in the position of the main character.

In the story, participants imagined taking a chemistry course, a subject in which they were told they did not perform well. They read that at the time of the final exam they were one point below a C (a passing grade). They further read that, even though they had studied very hard, they did not feel that they were retaining any information. As a result, they created a cheat sheet as a backup. During the final examination, they were asked a very confusing question about amino acids. They were informed that they tried for a few minutes to remember the correct answer.

Those in the unethical condition read that they could not remember the answer, so they used their hidden cheat sheet. They further read that they received a C+ but felt very guilty about cheating, believing they had done something morally wrong. In the ethical condition, participants read that they had remembered the answer so they did not use the hidden cheat sheet. They also read that they received a C+ and felt proud, believing they had done something morally right by not cheating.

The participants in the self-conditions read the story from a first-person perspective, and those in the third-person conditions read the exactly the same story from a third-person perspective, with “Chris” as the main character.

Four days later, in part 2, we asked questions about their memory of the story they had read. Participants rated their memory on the short version of the MCQ including only clarity (α = 0.94) and thoughts and feeling (α = 0.95). We measured thoughts and feelings with four items, adding two items to those used in study 1a: “I remember how I felt at the time I read about the event” and “I remember what I thought at the time I read about the event.” Additionally, we used the AMQ from study 2.

Results.

A MANOVA using participants’ ratings for the all measures (AMQ, clarity, thoughts and feelings) as dependent variables and actor and nature of the act as between-participants factors showed a significant interaction effect [F(3, 188) = 3.51, P = 0.016, ηp2 = 0.05].

AMQ responses.

A 2 × 2 (actor × nature of act) ANOVA on the AMQ revealed a significant effect for the interaction of actor and nature of the act [F(1, 190) = 10.37, P = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.05] (Fig. S2). Within the self conditions, participants in the unethical condition reported lower memory of the story (M = 1.20, SD = 0.42) than did participants in the ethical condition (M = 1.92, SD = 1.33) [F(1, 96) = 12.57, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12]. However, in the third-person conditions, there was no difference in memory between the ethical (M = 1.42, SD = 0.87) and unethical (M = 1.64, SD = 1.19) stories [F(1, 94) = 1.13, P = 0.29]. Additionally, one’s memory of one’s own unethical actions (M = 1.20, SD = 0.42) was weaker than one’s memory of Chris’ unethical actions (M = 1.64, SD = 1.19) [F(1,93) = 5.77, P = 0.018]. However, one’s memory of one’s own ethical actions (M = 1.92, SD = 1.33) was stronger than one’s memory of Chris’ ethical actions (M = 1.42, SD = 0.87) [F(1,97) = 4.92, P = 0.029].

MCQ responses.

A 2 × 2 (actor × nature of act) ANOVA on the clarity factor revealed a significant effect for the interaction of actor and nature of the act [F(1, 190) = 4.42, P = 0.037, ηp2 = 0.02]. As in the AMQ, the participants recalling their own unethical actions reported lower memory of the story (M = 1.54, SD = 1.42) than did participants remembering their own ethical actions (M = 2.07, SD = 1.42) [F(1, 96) = 5.01, P = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.05]. However, there was no difference in the third-person condition between memory of ethical (M = 1.56, SD = 0.93) and unethical (M = 1.68, SD = 0.97) acts [F(1, 94) = 0.35, P = 0.56]. One’s memory of one’s own unethical actions (M = 1.54, SD = 0.82) was not significantly different from one’s memory of Chris’ unethical actions (M = 1.68, SD = 0.97) [F(1,93) = 0.58, P = 0.45]. However, one’s memory of one’s own ethical actions (M = 2.07, SD = 1.42) was stronger than one’s memory of Chris’ ethical actions (M = 1.56, SD = 0.93) [F(1,97) = 4.33, P = 0.040]. We attribute this significant difference to a weaker memory for the actions of others than for one’s own actions.

As for the recalled thoughts and feelings, a 2 × 2 (actor × nature of act) ANOVA revealed a significant effect for the interaction of actor and nature of the act [F(1, 190) = 4.12, P = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.02]. Consistent with the results for clarity of memory, participants had a less clear recall of thoughts and feelings in the self-unethical condition (M = 1.72, SD = 1.10) than did participants in the self-ethical condition (M = 2.35, SD = 1.73) [F(1, 96) = 4.60, P = 0.035, ηp2 = 0.05]. However, in the third-person condition there was no difference between memory of ethical (M = 1.82, SD = 1.30) and unethical (M = 2.01, SD = 1.41) acts [F(1, 94) = 0.46, P = 0.50]. The thoughts and feelings scores for one’s own unethical actions (M = 1.72, SD = 1.27) were not significantly different from the scores for Chris’ unethical actions (M = 2.01, SD = 1.41) [F(1,93) = 1.27, P = 0.26]. The score on one’s memory of one’s own ethical actions (M = 2.35, SD = 1.73) was marginally higher than the score for the memory of Chris’ ethical actions (M = 1.82, SD = 1.30) [F(1,97) = 2.94, P = 0.090].

SI Study 4

Method.

Study 4 was a two-part online study. In part 1, participants were randomly assigned to a 2 × 2 × 2 (nature of the act: moral vs. neutral × valence of the act: positive vs. negative × delay in assessing memory: 30 min vs. 4 d) between-participants design. Participants were asked to read a story from a first-person perspective and later answer some questions about it (see SI Scenario Pair B, below, for neutral versions of the stories). We used the stories from study 3 for the moral conditions (SI Scenario Pair A, below). Specifically, we used the ethical version of the story from study 3 in the moral-positive act condition of study 4 and the unethical version of the story from study 3 in the moral-negative act condition of study 4.

For the neutral story, we replaced the actor’s choice of making a cheat sheet as a backup with hiring a tutor to help with examination preparation. As in the moral version of the story, in the neutral version of the story the actor could not remember the answer to a question in the examination. In the neutral-positive act condition, as in the moral-positive act condition, participants read that they remembered the answer because the tutor had covered the topic and that they received a C+ and felt very proud. Those in the neutral-negative act condition read that they could not remember the answer to the question because their tutor did not cover the topic and therefore they failed. They read that they felt very bad about this outcome.

Next, all participants completed a 30-min filler task which involved completing neutral scramble tasks and typing neutral sentences in allotted spaces on the computer screen. Those in the 30-min condition completed the AMQ memory measure right after completing the filler task. Those in the 4-d condition instead read that they would answer a few questions about the story they had read during part 2 of the study.

Four days later, those in the 4-d condition were asked to complete the same memory measure. Those in the 30-min condition were sent a different link and asked to complete a survey for an unrelated study.

Results.

Attrition.

In the 4-d condition, 72% of the participants who completed part 1 of the study also completed part 2. As noted, those in the 30-min condition were sent a different link and were asked to complete a survey for an unrelated study. We examined the number of people who returned to complete that survey (80%) to assuage potential concerns regarding attrition. Overall, the number of participants that returned to complete the second part of the study did not differ across conditions.

AMQ responses.

We ran a 2 × 2 × 2 (nature of the act × valence of the act × delay in assessing memory) ANOVA on the AMQ scores. Results yielded a main effect of delay in assessing memory [F(1, 249) = 200.36, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.45)] and a marginally significant main effect of valence of the act [F(1, 249) = 3.70, P = 0.056, ηp2 = 0.02]. We also found a significant interaction of delay in assessing memory × valence of the act [F(1, 249) = 3.98, P = 0.047, ηp2 = 0.02], a significant interaction of delay in assessing memory × nature of the act [F(1, 249) = 3.77, P = 0.053, ηp2 = 0.02], and a marginally significant interaction of nature of the act × valence of the act [F(1, 249) = 3.24, P = 0.073, ηp2 = 0.01]. Finally, as predicted, we found a significant three-way interaction of delay in assessing memory × nature of the act × valence of the act [F(1, 249) = 4.88, P = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.02] (Fig. 1).

Follow-up comparisons between the different groups indicated that among those who responded to the memory questions 30 min after reading the story, there was only a marginal main effect of the nature of the act, such that participants recalled the moral story more clearly than the neutral story [F(1, 144) = 3.60, P = 0.060, ηp2 = 0.02].

However, among those who responded to memory questions 4 d later, there was a main effect of valence of the act, such that the memory scores were lower for negative events [F(1, 105) = 4.90, P = 0.029, ηp2 = 0.05]. Consistent with the results of study 3, in the delayed conditions, we replicated the interaction effect of nature of the act × valence of the act [F(1, 105) = 5.13, P = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.05]. In the conditions in which participants read a moral story, participants who read that they cheated had a less clear memory of their actions (M = 2.06, SD = 1.34) than those who read they did not cheat (M = 3.25, SD = 1.38) [F(1, 55) = 13.75, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.20]. However, among those who read the neutral story, there was no difference in memory between negative (M = 2.93, SD = 1.29) and positive (M = 2.91, SD = 1.29) conditions [F(1, 50) = 0.001, P = 0.98].

Importantly, among the participant responded to the memory questions after 4 d, those who had read a moral-related story in which they were honest (i.e., moral nature of the act/positive valence of the act condition) did not remember it significantly differently from participants who had read a neutral story in which the act was positive (P = 0.35) or negative (P = 0.31). These results confirm our findings from studies 1b and 3 and suggest that differences in the memory of one’s own ethical and unethical actions arise not because one’s own memory of ethical behavior is enhanced but rather because one’s memory of one’s unethical experiences degrades. As such, the significant differences between the memory of one’s own ethical actions and of others’ unethical and ethical actions should be attributed to people generally having less vivid memories of others’ actions because they are not personally involved in the events.

SI Study 5

Method.

Study 5 was a two-part online study. In part 1, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (unethical vs. ethical) and then were asked to read the story from our previous studies for the ethical and unethical conditions. Participants took a first-person perspective and were asked to put themselves in the position of the main character.

One week later, participants were asked to answer questions about the story they had read. They were told that the goal of the study was to investigate how people remember and reflect on events from the past. We asked them to complete a task measuring their memory of the details of the story they read. Participants were presented with 18 statements, one at a time, and were asked to state (true or false) whether the details presented were part of the story they had read before. Half of the statements were actually true and used the information provided in the original story. For example, we created two statements, “I took a chemistry class during my undergraduate program,” and “I was majoring in anthropology,” from the original statement, “The last time I took chemistry, I had to do it for a semester for my bachelor’s degree in anthropology.” Half of the statements were false. For example, we created one statement “The cheat sheet was written on blue paper,” from the original statement, “As a result, I made a cheat sheet on white notebook paper as a backup.” In brief, the statements covered general details of the story. By using these true and false statements, we were able to assess the extent to which participants recalled the objective details of their past ethical or unethical actions as described in the story they had read.

Results.

The average objective memory scores were lower for participants who, 1 wk earlier, had read a story in which they cheated (M = 14.37, SD = 2.51) than for those who had read a story in which they behaved honestly (M = 15.23, SD = 1.38) [F(1, 87) = 3.97, P = 0.049, ηp2 = 0.04]. These results provide further support for unethical amnesia and show that people remember fewer details of their past unethical rather than ethical actions.

SI Study 6

Study 6 was a two-part online study that required participants to engage in a series of tasks and answer questions at two different points in time. At time 1, participants played a die-throwing game (as in ref. 20). In this game, participants were asked to throw a virtual six-sided die 20 times to earn points that would be translated to real dollars and added to participants’ final payment. The instructions of the game reminded participants that each pair of numbers on opposite sides of the die added up to 7: 1 vs. 6, 2 vs. 5, and 3 vs. 4. The instructions referred to the visible side that was facing up as “U” and the opposite, invisible side that was facing down as “D.” As in previous research (20) the instructions read: