Abstract

Objective

The main goal of this study was to determine the effects of incretins on type 2 diabetes (T2D) remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery for patients taking insulin.

Background

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic disease with potentially debilitating consequences. RYGB surgery is one of the few interventions that can remit T2D. Preoperative use of insulin, however, predisposes to significantly lower T2D remission rates.

Methods

A retrospective cohort of 690 T2D patients with at least 12 months follow-up and available electronic medical records was used to identify 37 T2D patients who were actively using a Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist in addition to another antidiabetic medication, during the preoperative period.

Results

Here, we report that use of insulin, along with other antidiabetic medications, significantly diminished overall T2D remission rates 14 months after RYGB surgery (9%) compared with patients not taking insulin (56%). Addition of the GLP-1 agonist, however, increased significantly T2D early remission rates (22%), compared with patients not taking the GLP-1 agonist (4%). Moreover, the 6-year remission rates were also significantly higher for the former group of patients. The GLP-1 agonist did not improve the remission rates of diabetic patients not taking insulin as part of their pharmacotherapy.

Conclusions

Preoperative use of antidiabetic medication, coupled with an incretin agonist, could significantly improve the odds of T2D remission after RYGB surgery in patients also using insulin.

Keywords: diabetes, incretin, insulin, obesity, remission, RYGB, surgery

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (“T2D” or “diabetes,” herein) has significant medical and socioeconomic implications.1 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery is an effective intervention in humans that remits T2D,2 with approximately 60% of patients achieving temporary resolution or durable T2D remission.3,4 RYGB has also been proposed as a therapy for T2D resolution even in cases where weight loss may not be the primary objective5 and particularly for cases with low body mass index (BMI) ranging from 25 to 35 kg/m2.6

Durable T2D remission has been associated with early-stage diabetes7 and significant percent excess body weight loss,8 whereas inability to achieve long-term remission has been associated with inadequate weight loss.9 Glycemic response to gastric bypass has also been correlated with BMI, duration of diabetes, fasting C peptide, and weight loss.10 Young age and low BMI (25–35 kg/m2) have also been associated with long-term T2D remission,6 whereas use of insulin, high HbA1c, and low percent excess body weight loss have been associated with decreased rate of remission after RYGB surgery.11 In the Swedish obese subjects study, 72% of patients experience remission of diabetes within 2 years after surgery but only 36% remained in remission after 10 years.12 In a recent study, patients not taking insulin before RYGB surgery had significantly higher remission rates than patients using insulin (53.8% vs 13.5%).3 Elsewhere, approximately 70% of patients using insulin did not remit diabetes 2 years after RYGB surgery, whereas among noninsulin users only approximately 15% of patients did not remit.13

In general, preoperative use of insulin is associated with low remission rates after RYGB surgery over 5 years.3,13 Here, we show that preoperative addition of incretins could significantly improve remission rates for this group of patients.

Methods

Basic Characteristics of Study Participants

A retrospective cohort of patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at Geisinger Clinic between January 1, 2004, and February 15, 2011,14 was used to identify 690 T2D patients with at least 12 months follow-up and available electronic medical records (EMR). Thirty-seven T2D patients were actively using a Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist (Byetta, Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, San Diego, CA), in addition to another antidiabetic medication, during the preoperative period. These 37 patients were matched (using a propensity model including age, HbA1c, serum insulin, and type of diabetes medication) to patients who were not using a GLP-1 agonist in the preoperative period (at a rate of 3 nonusers corresponding to 1 GLP-1 user). The same 37 GLP-1 users were also matched to 111 nonusers of GLP-1 who were prescribed an antidiabetic medication with or without insulin. GLP-1 users were also divided according to their insulin use, which created 4 groups of patients (Table).

Table. Preoperative Characteristics of GLP-1 Users and Nonusers According to Insulin.

| No Insulin (N = 57) | Insulin (N = 91) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| GLP-1 (N = 14) | No GLP-1 (N = 43) | P | GLP-1 (N = 23) | No GLP-1 (N = 68) | P | |

| Age mean (SD), yrs | 47.9 (7.8) | 48.8 (10.7) | 0.770 | 53.2 (6.7) | 53.7 (9.3) | 0.790 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 36% (n = 5) | 19% (n = 8) | 0.271 | 35% (n = 8) | 38% (n = 26) | 0.767 |

| Female | 64% (n = 9) | 81% (n = 35) | 65% (n = 15) | 62% (n = 42) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 100% (n = 14) | 100% (n = 43) | NA | 100% (n = 23) | 99% (n = 67) | 0.999 |

| Other | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) | 1% (n = 1) | ||

| Diabetes medication | ||||||

| Metformin | 79% (n = 11) | 95% (n = 41) | 0.089 | 74% (n = 17) | 62% (n = 42) | 0.292 |

| Other ISA | 50% (n = 7) | 30% (n = 13) | 0.209 | 30% (n = 7) | 46% (n = 31) | 0.203 |

| Sulfonylureas | 71% (n = 10) | 44% (n = 19) | 0.123 | 57% (n = 13) | 32% (N = 22) | 0.039 |

| HbA1c, mean (SD), % | 7.0 (1.5) | 6.8 (1.1) | 0.571 | 8.6 (1.8) | 8.6 (1.6) | 0.880 |

| Glucose, mean (SD), mg/dL | 148 (72) | 118 (37) | 0.158 | 164 (98) | 166 (94) | 0.934 |

| Serum insulin, mean (SD), μU/mL | 24.7 (17.7) | 26.9 (36.7) | 0.774 | 20.5 (13.2) | 19.9 (14.4) | 0.871 |

P values were generated from 2-sample t test (continuous data) or χ2 test (categorical data).

ISA indicates other insulin-sensitizing agent.

These studies were approved by the Geisinger institutional review board for research. All participants provided informed written consent.

The antidiabetic medications used were metformin, sulfonylureas, and other insulin sensitizing agents [50% pioglitazone (Actos-Takeda, Deerfield, IL) and 50% rosiglitazone (Avandia-GSK, Philadelphia, PA)]. Insulin was prescribed to patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Some patients who were prescribed sulfonylureas and had poor glycemic control preoperatively were also prescribed insulin and/or the GLP-1 agonist for 6 to 9 months before surgery, in an injectable form (5 μg/0.02 mL or 10 μg/0.04 mL), administered once or twice a day. The decision for the additional preoperative use of GLP-1 agonist was based on poor glycemic control. Some patients were already on insulin and other antidiabetic medication, whereas, others were on just other antidiabetic medication (eg, sulfonylureas).

Definition of Type 2 Diabetes and Remission of Type 2 Diabetes

The definition of type 2 diabetes was according to guidelines by the American Diabetes Association.15 T2D was defined as fasting glucose more than 126 mg/dL or HbA1c more than 6.5%. Absence of diabetes was defined by fasting glucose less than 100 mg/dL and HbA1c less than 5.7%. Additional confirmation was obtained by examining EMR for the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code for T2D diabetes. Medications included biguanides (metformin), sulfonylureas, insulin, other insulin sensitizing agents, or combinations of different medications.

Remission of T2D after RYGB surgery was defined according to the established definition of diabetes criteria for “partial” and “complete” remission.16 Patients in “partial” remission (22% of patients with diabetes remission) were free of any use of antidiabetic medications, their fasted blood glucose levels were less than 125 mg/dL, and their HbA1c was less than 6.5% for a minimum of 12 months after surgery. Patients in “complete” remission (78% of patients with diabetes remission) had normal measures of glucose metabolism (ie, HbA1c < 5.7%, fasting glucose < 100 mg/dL) for at least 12 months after surgery, in the absence of active pharmacological therapy. An extra 2 months (12–14) were added to ensure normal laboratory test results (eg, glucose and HbA1c) that are often measured in the first 2 months after surgery and again within 2 months of their 12-month follow-up visit. Diabetes remission was also evaluated for 6 years after surgery (median follow-up: 3.5 years).

Statistical Analysis

The preoperative clinical characteristics of insulin and noninsulin users and GLP-1 users and nonusers were compared by 2-sample t tests (continuous data) and χ2 tests (categorical data). Long-term remission (ie, up to 6 years after surgery) was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier analysis and was compared between GLP-1 users and nonusers with log-rank test. All analyses were conducted with SAS (Version 9.3, Cary, NC) by using 2-sided tests and a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Preoperative Use of Insulin Is Associated With Decreased Diabetes Remission but GLP-1 Use Improves Early Remission Rates

Four groups of T2D patients undergoing RYGB surgery and using different types of antidiabetic medication were identified and categorized according to their insulin and/or GLP-1 use (Table). The only 2 groups that differed significantly were among the sulfonylurea and insulin users who were prescribed more heavily the GLP-1 agonist (Table).

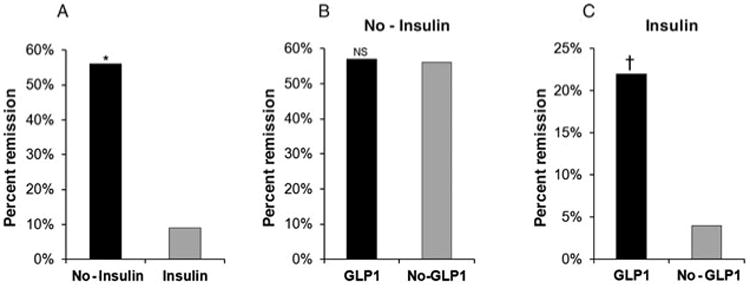

Diabetic patients who were prescribed insulin (along with another antidiabetic medication) before surgery had significantly diminished probability for diabetes remission (9%) at 14 months after RYGB surgery, compared with diabetic patients not taking insulin (56%, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A). After stratifying according to GLP-1 use, we found no significant effects by GLP-1 on noninsulin users who were prescribed other antidiabetic medications (Fig. 1B). Insulin users who were prescribed an antidiabetic medication as well as GLP-1 agonist, however, had significantly higher remission rates (22%) compared with insulin users (plus other antidiabetic medication) who were not prescribed GLP-1 (4%, P < 0.011) (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Effects of preoperative use of antidiabetic medication, insulin, and GLP-1 on diabetes remission (percent) 14 months after RYGB surgery. (A) Additional use of insulin among patients using other antidiabetic medication significantly reduced the odds of diabetes remission (*P < 0.0001). (B) GLP-1 use had no significant (NS) effect on diabetes remission for patients using antidiabetic medication but not using insulin. (C) GLP-1 use significantly improved the odds of diabetes remission among patients using a combination therapy of antidiabetic medication plus insulin (†P = 0.011). Patients were in partial or complete diabetes remission.

Preoperative Use of GLP-1 Increases Long-term Diabetes Remission in Patients Using Insulin

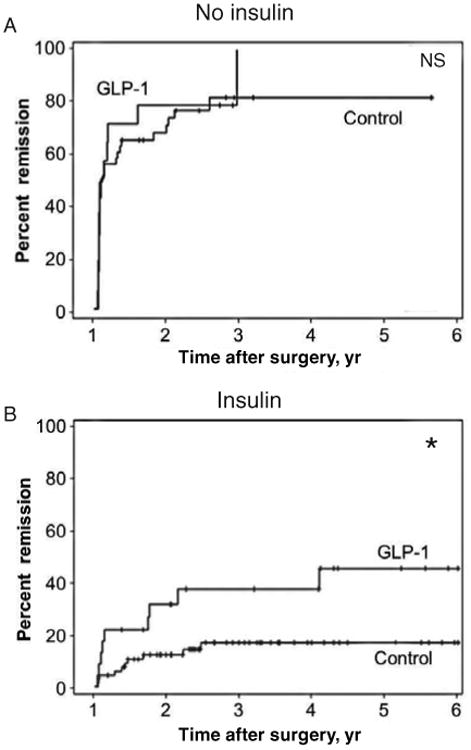

Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to determine the course of diabetes remission over 6 years. We found that diabetic patients prescribed GLP-1 (irrespective of insulin) had higher remission rates but not at statistically significant levels (log-rank P = 0.095) (data not shown). After stratifying the patients according to preoperative use of insulin, non–insulin-using patients who were prescribed GLP-1 (with or without another antidiabetic medication) did not benefit in terms of diabetes remission (log-rank P = 0.776) (Fig. 2A). Insulin-using patients, who were also prescribed preoperatively the GLP-1 agonist (in addition to another antidiabetic medication), however, had significantly higher remission rates than patients not using insulin (log-rank P = 0.016) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the long-term effect of preoperative antidiabetic medication, insulin, and GLP-1 on diabetes remission (percent) for up to 6 years after RYGB surgery. (A) GLP-1 had no significant (NS) effect on diabetes remission in patients using antidiabetic medication compared with patients using just antidiabetic medication (control). (B) GLP-1 significantly improved the chances of diabetes remission in patients using combination therapy of antidiabetic medication plus insulin, compared with patients using just combination therapy of antidiabetic medication plus insulin (control, *log-rank P = 0.016). Patients were in partial or complete diabetes remission.

Discussion

The majority of diabetic patients (∼60%) enter into a state of remission after RYGB surgery.17 The patients who do not remit are usually the ones who have advanced, long-term diabetes13 and approximately 70% of them are prescribed insulin in addition to metformin or other antidiabetic medication. Here, we report that patients prescribed insulin along with another antidiabetic medication had significantly higher rates of diabetes remission if they were also prescribed preoperatively a GLP-1 agonist.

Groups of patients were stratified according to insulin and/or GLP-1 use and were matched for HbA1c, fasting glucose levels, age, and gender distribution. First, we found that diabetic patients who were prescribed insulin before surgery had significantly diminished probability of diabetes remission (9%), compared with diabetic patients not taking insulin (56%), which is in agreement with previous reports.3,13 Insulin-using patients, however, that were also prescribed GLP-1, had higher remission rates (22%) than insulin users not prescribed GLP-1 (4%). GLP-1 had no effect on remission rates for diabetic patients not taking insulin suggesting that it can only benefit the former type of patients. In addition, Kaplan-Meier analysis over 6 years showed that patients taking insulin as well as GLP-1 had higher long-term (6 years) remission rates than patients using insulin alone. Patients who require insulin, in addition to an insulin sensitizer, usually have beta cells dysfunction18,19 but we did not have C peptide or meal challenge data to confirm this possibility in our patients.

Two recent studies showed that enhanced GLP-1 response to meal intake after RYGB surgery, or the use of an antagonist to the GLP-1 receptor, do not implicate the GLP-1 pathway in long-term remission of diabetes after RYGB surgery.20,21 A key difference with our study, however, is that the GLP-1 agonist was prescribed to our patients before surgery. None of our patients in remission took GLP-1 agonist (or any other antidiabetic medication) after surgery. It is noteworthy that most GLP-1 users, whether on insulin or not, were also prescribed sulfonylureas instead of metformin or other antidiabetic medication. Others have shown that the use of combination therapy of sulfonylurea, insulin, and GLP-1 in typical diabetic patients has greater benefit than combinations of metformin and GLP-1.22 Moreover, combined use of sulfonylurea, insulin, and a GLP-1 receptor agonist was found to improve glycemic control in diabetic patients.23 Hence, it is possible that the combination therapies that include sulfonylurea, insulin, and GLP-1 may have a more potent effect on diabetes remission than other combinations of antidiabetic therapies. These data also identify a specific category of patients (ie, those taking insulin) with severe diabetes who may benefit from incretin use, potentially, irrespective of BMI. This possibility would require extensive validation in future studies and clinical trials.

The study described here has some limitations. Duration of diabetes, for instance, was not available because some patients were diagnosed upon enrolment but likely had diabetes before entering our bariatric surgery program. In addition, some patients who were already on antidiabetic medication could not recall the time of their diagnosis and, in the absence of past EMR, duration could not be determined. This issue is further compounded by the unknown duration of prediabetes. Yet, we have found that use of insulin and age can be proximal surrogates to duration of diabetes (in general, older patients are likely to have had type 2 diabetes for longer time than younger patients) and we ensured that pairs of groups that were compared were stratified according to insulin use and were of almost identical ages. Another limitation is that our data cover a 6-year follow-up. It would be of interest to observe the duration of diabetes and its potential relapse in longer periods of time (>10 years postoperatively) and determine whether GLP-1 use before surgery offers even longer-term protection against the possibility of diabetes relapse.

Conclusions

Recently, incretins were reported to be associated with increases risk of pancreatitis and preneoplastic lesions,24 but the benefits may outweigh the potential risks.25 Use of the GLP-1 agonist in our study was restricted to time before surgery. Clinical trials and long-term observations would be required to properly evaluate the potential adverse effects of preoperative use of incretin mimetics among the type of patients described in this study. In summary, our data show that preoperative use of antidiabetic medication involving insulin and a GLP-1 agonist increased more than fivefold the probability of diabetes remission after RYGB surgery via a yet-to-be-determined mechanism. This finding warrants further evaluation of the preoperative use of incretin mimetics among insulin-using patients who otherwise have poor T2D remission rates after RYGB surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the thousands of participating RYGB surgery patients at Geisinger Health System. The author contributions were as follows: G.C.W. selected all patients and related information from databases and performed all statistical analyses; G.S.G. helped with the study design and manuscript preparation; P.B., A.T.P., J.G., W.E.S., and A.I. performed all RYGB surgeries and helped with the preparation of the manuscript; D.D.R. provided expert analysis of the diabetes data and interpretations of possible effects by combination therapies; C.D.S. admitted all the patients to the weight loss bariatric program at Geisinger Clinic and prescribed medications; and G.A. conceived and designed the study, participated in patient selection, and wrote the manuscript.

This research was supported by research funds from the Geisinger Health System and the National Institute of Health grants DK072488 (G.S.G., C.D.S., G.A.), DK088231 (G.S.G.), and DK091601 (G.S.G.).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflict of interest to report as it relates to this study.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1567–1576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackstone R, Bunt JC, Cortes MC, et al. Type 2 diabetes after gastric bypass: remission in five models using HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and medication status. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pournaras DJ, Osborne A, Hawkins SC, et al. Remission of type 2 diabetes after gastric bypass and banding: mechanisms and 2 year outcomes. Ann Surg. 2010;252:966–971. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181efc49a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varela JE. Bariatric surgery: a cure for diabetes? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14:396–401. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283468e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang CK, Shabbir A, Lo CH, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for the treatment of type II diabetes mellitus in Chinese patients with body mass index of 25–35. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1344–1349. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0408-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chikunguwo SM, Wolfe LG, Dodson P, et al. Analysis of factors associated with durable remission of diabetes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamza N, Abbas MH, Darwish A, et al. Predictors of remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus after laparoscopic gastric banding and bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:691–696. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.03.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deitel M. Update: why diabetes does not resolve in some patients after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21:794–796. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon JB, Chuang LM, Chong K, et al. Predicting the glycemic response to gastric bypass surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:20–26. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2003;238:467–484. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089851.41115.1b. discussion 84–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arterburn DE, Bogart A, Sherwood NE, et al. A multisite study of long-term remission and relapse of type 2 diabetes mellitus following gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2013;23:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0802-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood GC, Chu X, Manney C, et al. An electronic health record-enabled obesity database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(suppl 1):S11–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buse JB, Caprio S, Cefalu WT, et al. How do we define cure of diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2133–2135. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerhard GS, Styer AM, Wood GC, et al. A role for fibroblast growth factor 19 and bile acids in diabetes remission after roux-en-y gastric bypass. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1859–1864. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page KA, Reisman T. Interventions to preserve beta-cell function in the management and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:252–260. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0363-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison LB, Adams-Huet B, Raskin P, et al. beta-cell function preservation after 3.5 years of intensive diabetes therapy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1406–1412. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jimenez A, Casamitjana R, Flores L, et al. GLP-1 and the long-term outcome of type 2 diabetes mellitus after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in morbidly obese subjects. Ann Surg. 2013;257:894–899. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b8603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jimenez A, Casamitjana R, Viaplana-Masclans J, et al. GLP-1 action and glucose tolerance in subjects with remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus after gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2062–2069. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar A. Second line therapy: type 2 diabetic subjects failing on metformin GLP-1/DPP-IV inhibitors versus sulphonylurea/insulin: for GLP-1/DPP-IV inhibitors. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 2):21–25. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia) Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:910–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler PC, Elashoff M, Elashoff R, et al. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin-based therapies: are the GLP-1 therapies safe? Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2118–2125. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nauck MA. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin-based therapies: the benefits by far outweigh the potential risks. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2126–2132. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]