Abstract

Objective

In the Weight Loss Maintenance (WLM) Trial, a personal contact (PC) intervention sustained greater weight loss relative to a self-directed (SD) group over 30 months. This study investigated the effects of continued intervention over an additional 30 months and overall weight change across the entire WLM Trial.

Methods

WLM had 3 phases. Phase 1 was a 6-month weight loss program. In Phase 2, those who lost ≥4 kg were randomized to a 30-month maintenance trial. In Phase 3, PC participants (n = 196, three sites) were re-randomized to no further intervention (PC-Control) or continued intervention (PC-Active) for 30 more months; 218 SD participants were also followed.

Results

During Phase 3, weight increased 1.0 kg in PC-Active and 0.5 kg in PC-Control (mean difference 0.6 kg; 95% CI:−1.4 to 2.7; P = 0.54). Mean weight change over the entire study was −3.2 kg in those originally assigned to PC (PC-Combined) and −1.6 kg in SD (mean difference −1.6 kg; 95% CI:−3.0 to −0.1; P = 0.04).

Conclusions

After 30 months of the PC maintenance intervention, continuation for another 30 months provided no additional benefit. However, across the entire study, weight loss was slightly greater in those originally assigned to PC.

Introduction

More than two-thirds of adult Americans are now overweight or have obesity (1,2). Fortunately, even modest (5-10%) weight loss has important health benefits, including a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes and hypertension (3,4). Well-designed behavioral interventions typically have resulted in clinically significant 6-month weight loss for one-half to two-thirds of adult participants (5-7). The current challenge is sustaining weight loss (8). To date, few randomized clinical trials have formally tested the effects of behavioral weight loss maintenance strategies; the majority have had follow-up periods of 2 years or less (9). While recent meta-analyses have confirmed that those who participate in weight loss maintenance interventions experience significantly less weight regain compared to controls, there is a paucity of evidence on the long-term sustainability of these interventions (10-12). Moreover, it is unknown whether extending the duration of efficacious weight loss maintenance interventions results in better outcomes, as has been demonstrated in short-term weight loss trials (13).

The Weight Loss Maintenance (WLM) Trial was a multi-center (four sites), randomized trial that compared strategies for maintaining weight loss in high-risk adults who lost at least 4 kg during an initial intensive weight loss intervention (14). After 30 months, participants randomized to a monthly personal contact (PC) intervention regained significantly less weight than those in a self-directed (SD) condition (15). For the current study, we extended follow-up of the PC and SD cohorts for an additional 30 months, and those originally randomized to PC underwent a second randomization to continued PC intervention or no further intervention. The primary aim of the current analysis is to examine the effects of an additional 30 months of the PC intervention compared to no further intervention. A secondary aim was to compare the overall effects of the PC intervention compared to the SD condition across the entire WLM Trial.

Methods

Design

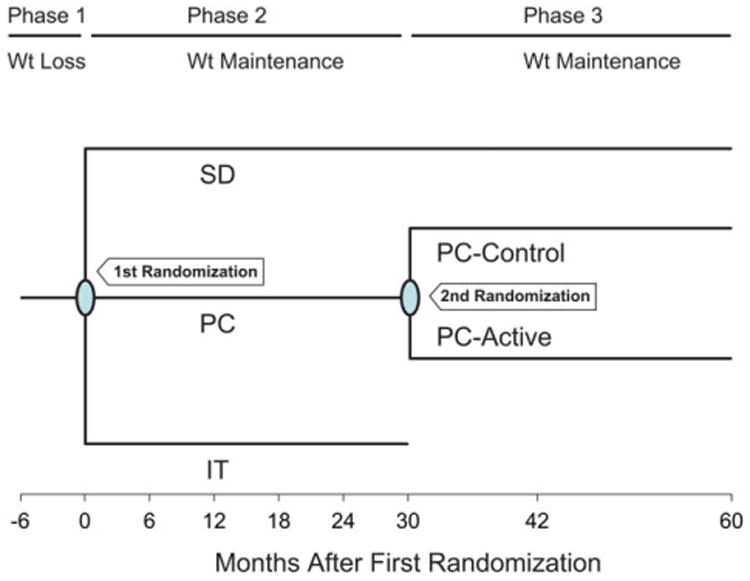

WLM was conducted in three phases (Figure 1). A 6-month weight loss intervention (Phase 1) was followed by a randomized 30-month weight loss maintenance trial (Phase 2) that compared two interventions [PC and an interactive technology-based intervention (IT)] to SD. Results of Phases 1 and 2 have been published (5,15). Three of the four Phase 1 and 2 centers also participated in a third phase that lasted an additional 30 months. During Phase 3, PC participants at these sites were re-randomized to either continued intervention (PC-Active) or no further intervention (PC-Control). SD participants received no further intervention but continued to be followed. Because the IT intervention did not differ significantly from the SD condition, follow-up of comparable IT-Active and IT-Control arms was discontinued midway through Phase 3 and those data are not reported here (15). The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board at each participating site, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Design of the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial. SD = self-directed; PC = personal contact; IT = interactive technology. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Participants

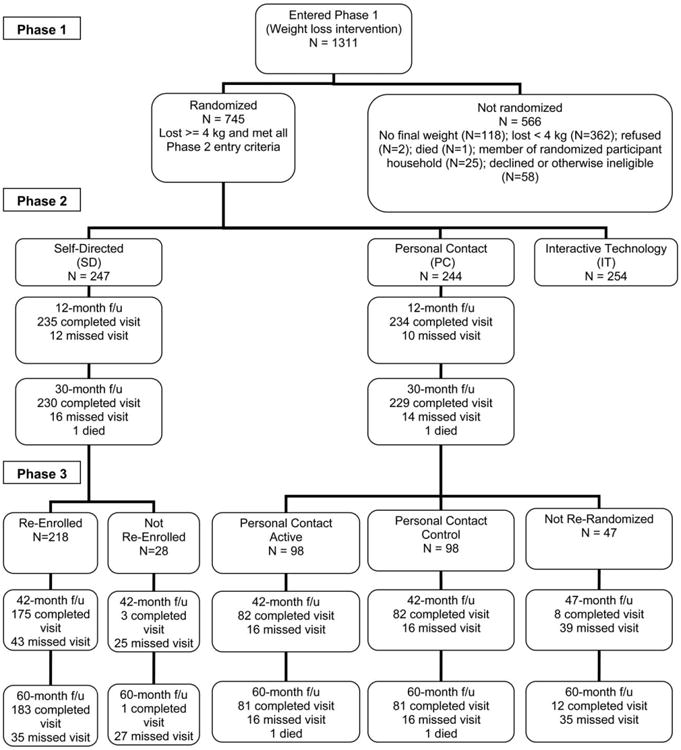

Participants were adults with a body mass index (BMI) of 25-45 kg/m2 who were taking medication for hypertension and/or dyslipidemia. Major exclusion criteria for Phase 1 were medication-treated diabetes mellitus, a recent cardiovascular event, and weight loss of > 9 kg in the last 3 months. The primary criterion for randomization into Phase 2 was weight loss of at least 4 kg during Phase 1. All Phase 2 participants at participating sites were invited to continue into Phase 3, and 414 agreed to do so (Figure 2). Of these, two died during Phase 3 and are excluded from any analyses.

Figure 2.

Participant flow during Phases 1, 2, and 3 of the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial at the Baltimore, Baton Rouge, and Durham clinical centers.

Participant flow

Individuals meeting prescreening criteria attended screening visits, after which eligible participants (N = 1,311) began the Phase 1 behavioral weight-loss program (Figure 2). Those who completed Phase 1 and met criteria for Phase 2 were randomized (N = 745). The Phase 2 randomization assignments were stratified by clinic, race, and weight loss during Phase 1. The Phase 3 randomization assignments were stratified by site, Phase 2 treatment group, and Phase 2 weight change through 18 months.

Measurements

Data collection occurred at the beginning of Phase 1 (“entry”), the end of Phase 1 (first randomization) and every 6 months after the first randomization for 30 months. During Phase 3, data collection visits occurred twice, 12 and 30 months after the second randomization, which corresponds to 42 and 60 months after the first randomization. Measurements were obtained by trained, certified staff masked to treatment arm. At each visit, weight was measured in duplicate with a calibrated digital scale.

Initial weight loss intervention (Phase 1)

Phase 1 was a 6-month, group-based, weekly behavioral intervention. Intervention goals were weight loss of approximately 1-2 lb/week, 180 min/week of moderate physical activity (PA), reduced caloric intake, and consumption of the DASH diet (5). Participants were taught to keep food and PA self-monitoring records and to calculate caloric intake.

PC intervention (Phases 2 and 3)

The goal of the PC intervention was maintenance of Phase 1 weight loss or additional weight loss if desired, continued adherence to the DASH diet, and increasing moderate PA to at least 225 min/week. The intervention reinforced key theoretical constructs originally presented in Phase 1 (problem solving, accountability, self-monitoring, increased self-efficacy, goal setting), with an emphasis on maintenance of behavior change (relapse prevention, self-monitoring of weight) for preventing weight regain (16).

During Phase 2, PC participants had telephone contact with inter-ventionists trained in motivational interviewing and behavioral weight management for ∼15 min/month, except every fourth month when they had a 45-60 min individual, face-to-face contact. Those randomized to PC-Active in Phase 3 attended four, weekly group sessions. After these sessions, PC-Active participants continued monthly phone contacts, employing the same contact schedule, format, and general content as in Phase 2. Each PC-Active contact began with a reported weight and a review of progress, including frequency of food diaries and self-weighing, minutes/week of exercise, and progress toward goals. PC-Controls received no further intervention after completing Phase 2.

SD intervention (Phases 2 and 3)

SD participants received printed lifestyle guidelines with diet and physical activity recommendations at the Phase 2 randomization visit and met briefly with a study interventionist after the 12-month data collection visit (15). They received no further instructions or visits during the remainder of Phases 2 or 3.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was Phase 3 weight change (beginning to end of Phase 3). Other outcomes were change in weight across the whole study (from start of Phase 1 to end of Phase 3) and 5 dichotomous measures of weight change from study entry to end of study: at or below study entry weight, maintenance of at least 4 kg weight loss from study entry, at least 5% below entry weight, no more than 3% weight gain from first randomization, and no more than 3% weight gain from second randomization.

Analysis

For the primary comparison of PC-Active versus PC-Control, we used a general linear model with normal errors to regress Phase 3 weight change on treatment status while adjusting for weight change from study entry to end of Phase 2, age, site, gender, race, and an interaction term of gender and race. This analysis was limited to the 196 PC participants who were re-randomized into Phase 3, less the two who died during Phase 3 (Figure 2). Comparisons of binary weight change outcomes measured from study entry used logistic regression analyses adjusting for entry weight, age, site, gender, race, and an interaction term of gender and race. Analyses of binary weight change outcomes measured from start of Phase 2 or start of Phase 3 adjusted for weight at those time points in place of entry weight.

When we failed to reject the null hypothesis of no continued effect from continued PC intervention, we combined PC-Active and PC-Control for comparisons of the overall weight loss experience (Phases 1-3) versus SD. These latter analyses were generally limited to the 414 individuals who re-enrolled in Phase 3 (less two who subsequently died). However, for our analysis of absolute weight change from entry we included all 491 participants who were initially randomized to PC and SD in Phase 2 (less the four who died during Phases 2 or 3). Adjustment variables were the same as those used for the PC-Active versus PC-Control comparisons. We also compared weight change between successive measurement points for participants in the SD and combined PC conditions, again using all 491 SD and PC participants. For this latter analysis we expressed the weight change estimates as annualized weight change.

We used multiple imputation (17,18), including the 28 SD participants and 47 PC participants who initially opted out of Phase 3, to replace missing end-of-study weights, missing interim weights, and other missing data. Results presented in our figures and tables are the average of separate, identical analyses performed on each of these five complete imputation datasets, with appropriate adjustment of standard errors to incorporate the added variability from the imputation process. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2. Linear models were fit using PROC MIXED and logistic models using PROC GLIMMIX. All weight change outcomes shown in Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 3a, b are adjusted for the covariates in the models described above using ESTIMATE. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, and all P-values are two-sided.

Table 2. Percent of participants who met various weight change criteria at end of Phase 3a.

| Statistical tests | Significance levelb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| All | SD | PC | PC-Active | PC-Control | PC-Active vs. PC-Control | PC vs. SD | |

| N | 412 | 218 | 194 | 97 | 97 | – | – |

| At or below entry weight [95% CI] | 70% [65-74%] | 63% [56-69%] | 77% [70-83%] | 75% [65-83%] | 79% [69-86%] | 0.54 | 0.002 |

| Maintained at least 4 kg loss from entry [95% CI] | 37% [32-42%] | 36% [30-43%] | 40% [33-47%] | 36% [27-46%] | 44% [34-54%] | 0.39 | 0.48 |

| At least 5% below entry weight [95% CI] | 32% [28-37%] | 27% [21-34%] | 37% [30-44%] | 37% [28-48%] | 38% [29-49%] | 0.90 | 0.052 |

| No more than 3% above weight at 1st randomization (Phase 2) [95% CI] | 31% [27-36%] | 26% [20-32%] | 36% [29-43%] | 37% [28-48%] | 35% [26-45%] | 0.67 | 0.044 |

| No more than 3% above weight at 2nd randomization (Phase 3) [95% CI] | 64% [59-69%] | 65% [58-71%] | 63% [56-70%] | 61% [51-71%] | 64% [54-73%] | 0.79 | 0.75 |

The end of Phase 3 is 66 months after start of Phase 1, 60 months after randomization into Phase 2. Data limited to the 414 participants from the Baltimore, Durham, and Baton Rouge clinical centers who were initially enrolled in either the SD or PC interventions for the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial and who subsequently enrolled in Phase 3 (less the two who died during Phase 3).

Two-tailed significance levels based on logistic regression analyses adjusting for age, site, gender, race and race-gender interaction. For outcomes reflecting change from study entry, the models also adjust for entry weight, while for outcomes reflecting change from the start of Phase 2 or Phase 3, the models are adjusted for weight at those points in time instead of entry weight.

SD = self-directed; PC = personal contact.

Table 3. Annualized change in weight (kg/y) during visit intervals in Phase 2 and 3a.

| Time interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Baseline to 6 m | 6 m to 12 m | 12 m to 18 m | 18 m to 24 m | 24 m to 30 m | 30 m to 42 m | 42 m to 60 m | |

| All | 0.49 [0.45 to 0.54] | 0.50 [0.46 to 0.55] | 0.38 [0.34 to 0.43] | 0.14 [0.11 to 0.18] | 0.10 [0.08 to 0.13] | 0.06 [0.04 to 0.09] | 0.01 [0.00 to 0.03] |

| SD | 0.68 [0.62 to 0.74] | 0.59 [0.53 to 0.65] | 0.56 [0.50 to 0.62] | 0.09 [0.06 to 0.14] | −0.02 [−0.01 to 0.05] | 0.02 [0.01 to 0.05] | 0.02 [0.01 to 0.05] |

| PC | 0.29 [0.23 to 0.35] | 0.41 [0.35 to 0.48] | 0.21 [0.16 to 0.27] | 0.20 [0.15 to 0.26] | 0.22 [0.17 to 0.28] | 0.10 [0.07 to 0.15] | 0.00 [0.00 to 0.02] |

| P-valueb | 0.0004 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.044 | 0.15 | 0.45 |

Data limited to 491 participants (less the four who subsequently died) from the Baltimore, Durham, and Baton Rouge clinical centers who were initially enrolled in either the SD or PC interventions for the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial.

P-value for comparison of slope of PC and slope of SD adjusting for site, age, race, gender, race-gender interaction, and starting weight.

SD = self-directed; PC = personal contact; [95% CI].

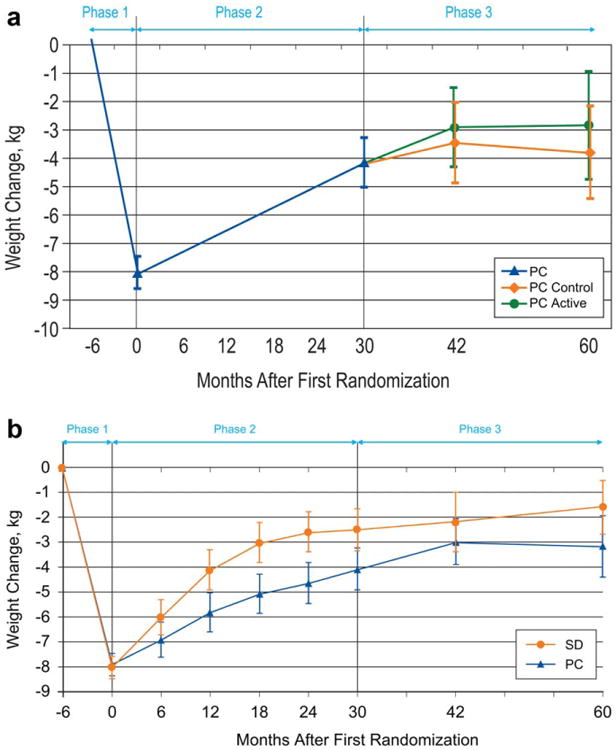

Figure 3.

(a) Adjusted mean (95% CI) weight change from study entry for the 196 participants in the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial who were assigned to the personal contact (PC) intervention during Phase 2 and who subsequently were randomized to receive continued PC intervention (PC-Active) or no further intervention (PC-Control) during the 30-month Phase 3 period. (b) Adjusted mean (95% CI) weight change from entry for all 491 participants originally randomized to the self-directed (SD) and PC conditions. Data are limited to participants from the Baltimore, Baton Rouge, and Durham clinical centers and do not include the four individuals who subsequently died. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Power

The maximum sample size for Phase 3 was the number of persons who enrolled in Phase 2 at the three participating sites. Given that 196 agreed to be re-randomized, we had 90% power to detect a 2.6 kg difference in weight change between PC-Active and PC-Control.

Results

The characteristics of participants randomized to the PC-Active and PC-Control groups were generally very similar, although the former had 33% more African-American women and 32% fewer African-American men (Table 1). Table 1 also shows similar information for the original PC and SD cohorts as randomized at the start of Phase 2 (n = 489). For both the PC-Active and PC-Control groups, 84% of participants provided a weight at the 42-month follow-up visit and 83% provided a weight at 60-month follow-up. Comparable statistics for the 218 SD participants who initially agreed to participate in Phase 3 were 80% and 84% (Figure 2). Although 28 SD and 47 PC participants initially opted out of Phase 3, staff nonetheless managed to collect some follow-up weights on these individuals as well (Figure 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of participantsa.

| Among PC, those re-randomized at 30 m to: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| All (n = 489) | SD (n = 246) | PC (n = 243) | PC-Active (n = 98) | PC-Control (n = 98) | |

| Age, mean (SD), yb | 55.1 (9.0) | 55.4 (8.8) | 54.9 (9.3) | 55.1 (9.1) | 55.1 (9.2) |

| Race/ethnicity and sex | |||||

| African-American | |||||

| Women | 158 (32%) | 80 (33%) | 78 (32%) | 36 (37%) | 27 (28%) |

| Men | 74 (15%) | 33 (13%) | 41 (17%) | 13 (13%) | 19 (19%) |

| Non-African-American | |||||

| Women | 164 (34%) | 85 (35%) | 79 (33%) | 31 (32%) | 32 (33%) |

| Men | 93 (19%) | 48 (20%) | 45 (19%) | 18 (18%) | 20 (20%) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | |||||

| Entry | 95.7 (16.7) | 95.2 (16.0) | 96.1 (17.3) | 93.9 (16.4) | 96.7 (18.4) |

| 1st randomization (Phase 2) | 87.8 (16.0) | 87.3 (15.4) | 88.3 (16.7) | 86.0 (15.8) | 88.5 (17.6) |

| 2nd randomization (Phase 3) | 92.6 (17.4) | 92.9 (16.7) | 92.2 (17.8) | 90.1 (16.9) | 92.1 (18.6) |

| Phase 1 weight change | −7.9 (3.7) | −8.0 (3.5) | −7.8 (3.8) | −7.9 (3.8) | −8.2 (4.2) |

| Phase 2 weight change | 4.8 (6.1) | 5.7 (6.4) | 3.9 (5.0) | 4.1 (4.9) | 3.6 (4.8) |

| Phase 1 and 2 weight change | −3.1 (6.4) | −2.3 (6.2) | −3.9 (6.1) | −3.8 (5.5) | −4.6 (6.8) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | |||||

| Entry | 34.1 (4.8) | 34.1 (4.9) | 34.1 (4.8) | 33.6 (4.8) | 33.9 (4.8) |

| 1st randomization (Phase 2) | 31.3 (4.7) | 31.2 (4.7) | 31.3 (4.7) | 30.8 (4.7) | 31.1 (4.7) |

| 2nd randomization (Phase 3) | 33.0 (5.2) | 33.2 (5.2) | 32.7 (5.2) | 32.3 (5.1) | 32.3 (5.1) |

| Incomeb | |||||

| <$60 K | 43% | 40% | 47% | 48% | 48% |

| ≥$60 K | 57% | 60% | 53% | 52% | 52% |

| Educationb | |||||

| Some college or less | 39% | 40% | 38% | 36% | 34% |

| College degree | 61% | 60% | 62% | 64% | 66% |

Data limited to participants from the Baltimore, Durham, and Baton Rouge clinical centers who were initially enrolled in either the SD or PC interventions for the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial.

At entry.

SD = self-directed; PC = personal contact.

Intervention adherence

During Phase 3, the average number of expected PC-Active contacts was approximately 30. The actual number of contacts [median (Q1, Q3)] was 23 (15,26), which is a median contact completion rate of 77%. Of these contacts, the vast majority were completed by telephone [median (Q1, Q3) = 20(14,24)].

Comparison of PC-Active and PC-Control during Phase 3

Figure 3a displays the weight experience of the PC-Active and PC-Control arms over the full course of the study; data are combined for study entry through the start of Phase 3. Mean (SD) weight gain measured from the start of Phase 3 was 1.0 kg (3.4) in PC-Active and 0.5 kg (6.1) in PC-Control [adjusted mean difference 0.6 kg (95% CI: −1.4 to 2.7), P = 0.55]. Table 2 displays the percent of individuals who met various criteria for weight outcomes. For each criterion, we observed no significant difference between PC-Active and PC-Control.

Comparison of SD and combined PC participants across Phases 1, 2, and 3

After initial mean weight loss during Phase 1, both PC and SD participants experienced weight regain (Figure 3b). Although the differences between the PC and SD groups appeared to be diminishing at the time of our primary (30-month) outcome analysis (15), they subsequently stabilized and the mean difference of −1.6 kg (95% CI:−3.1 to −0.1; P = 0.038) at 60 months post initial randomization was nearly identical to that observed at 30 months.

Of the 412 participants who opted to continue in Phase 3, 70% remained below entry weight at the end of the study (Table 2), with the percent for the combined PC-Active and PC-Control groups being significantly higher than the corresponding percent in SD (77% vs. 63%, P = 0.002). The percent of participants who maintained at least 5% below entry weight was borderline significantly higher in the combined PC group compared to SD (37% vs. 27%, P = 0.052). In terms of weight change post initial randomization (i.e., following initial weight loss), 36% of PC participants had final weights no more than 3% above their initial (Phase 2) randomization weight compared to only 26% of SD participants (P = 0.044). However, weight change post second (Phase 3) randomization did not differ between PC and SD.

Rate of weight regain

Trajectory of weight regain appeared to decline over time (Figure 3), being most rapid in the initial months of Phase 2 and largely flattening out during Phase 3. This is further illustrated in Table 3, which provides the average within-subject weight change between successive visits in the trial. To facilitate comparisons over time, the slopes are expressed in units of kg/y. Mean weight regain in SD was particularly rapid in the initial months of Phase 2, for example, 0.68 kg/y over the first 6 months post-randomization, in comparison to 0.29 kg/y in PC-combined. By the end of Phase 3, mean weight regain was extremely slow in both SD and PC, only 0.02 and 0.00 kg/y, respectively, and 0.01 kg/y overall.

Discussion

WLM is the longest randomized trial that prospectively tested the effects of behavioral weight loss maintenance interventions in persons who previously lost weight. The current study found that, among participants who lost at least 4 kg in a 6-month, group-based behavioral weight loss intervention and then completed 30 months of a behavioral weight loss maintenance intervention with monthly brief contacts with an interventionist, continued intervention for an additional 30 months did not significantly improve weight outcomes. Still, across the entire 66 months of the study, 60 of which focused on weight loss maintenance, mean weight loss in those originally assigned to the PC intervention was slightly greater than mean weight loss in the SD group, with a net mean difference of 1.6 kg. Consistent with these findings, 77% of Phase 3 participants initially assigned to the PC intervention had an end of study weight that was at or below their study entry weight compared to 63% in SD; 37% of those initially assigned to PC maintained at least 5% below their initial study entry weight compared to 27% in SD. However, the benefits of the PC intervention on weight loss, even when statistically significant, were modest at best.

These results extend our previously reported results (15). In the initial 30-month weight loss maintenance phase of WLM (Phase 2), monthly brief PC provided modest benefit in sustaining weight loss relative to a control condition, while an internet-based intervention provided early but transient benefit (15). Similar to the current Phase 3 findings, 77% of PC participants maintained a weight at or below their initial study entry weight at the end of Phase 2 compared to 67% in SD. Moreover, the original weight loss differential between PC and SD in Phase 2 (−1.5 kg) was sustained over the additional 30 months of Phase 3 (−1.6 kg), without any apparent need for further PC intervention.

It is not clear why extending a behavioral weight maintenance intervention offering brief, monthly contacts with an interventionist was not effective relative to no further intervention. Contact completion rates were impressively high for an intervention being delivered 3 years after initially starting treatment [∼77% in Phase 3 vs. 91% in Phase 2 (15)]; therefore, this finding is not likely explained by low engagement. Our closer analysis of rates of weight change throughout the trial show that the PC intervention had the strongest effect on slowing down regain in the first 6 months of Phase 2. Weight regain slowed down towards the end of Phase 2, and the extremely slow rate of weight regain in Phase 3, in both SD and PC suggests that, similar to other studies (19,20), with increased time, less effort is required for persons to sustain weight loss, and continued intervention to reinforce behavioral skills may no longer be necessary. It is unclear, however, if approaches not used in our study (e.g., incentives, smart phones with tailored text messages, etc.) could have reinforced or “recharged” participants' weight management success.

Few studies have tested behavioral interventions designed to sustain weight loss once achieved, and even fewer have examined long-term weight loss maintenance beyond 3 years (8-12). While meta-analyses have concluded that behavioral weight loss maintenance interventions provide small to moderate, but clinically and statistically significant, benefits on weight regain (10-12), to our knowledge, other than pharmacologic studies (21) and the WLM Trial, only two other trials (16,22) have randomized participants to a behavioral weight maintenance intervention after meeting a predetermined weight loss criterion. Both the Study to Prevent Regain (STOP Regain) and the Treatment of Obesity in Underserved Rural Settings (TOURS) trials found that face-to-face and remotely-delivered [Internet (16) and telephonic (22)] weight maintenance interventions are superior to control in preventing weight regain at 18 and 12 months, respectively. Collectively, the findings of WLM, STOP Regain, and TOURS, and more recent research supporting combined telephonic and Web-based lifestyle interventions (23,24), suggest that weight management treatment can be delivered through multiple channels, an encouraging finding given the need for flexible, scalable and affordable interventions to address the chronic condition of obesity. Remotely delivered interventions not only greatly increase the dissemination of empirically supported weight maintenance interventions, particularly for underserved populations, they also provide a cost-effective alternative for examining longer follow-up periods in research.

The Look AHEAD Trial provides one of the largest (N = 5,145) and longest examinations of weight outcomes following intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) (25). Although this trial did not randomize participants to a weight maintenance intervention following a successful weight loss, ongoing lifestyle counseling focused on maintaining weight loss and increased levels of PA was offered during years 2-4 of the study. ILI participants achieved mean percent reduction in initial weight of 8.7, 6.5, 5.3, and 4.9% in years 1-4, respectively, and 45% maintained a 5% weight loss at 4 years. In the current study, 37% of PC participants achieved at least 5% weight loss at 5 years. WLM's PC intervention thus would appear to offer a less intensive approach to achieving generally comparable long-term weight loss to that seen with Look AHEAD's ILI intervention.

Importantly, 27% of WLM participants in the SD condition lost at least 5% below entry weight at 5 years, suggesting that a strong weight loss intervention that achieves sizeable weight reductions at 6 months (mean weight change during WLM Phase 1 was −5.8 kg) (5) promotes sustained effects in about a quarter of participants. Characterizing individuals who do not receive further intervention but achieve weight management success comparable to those receiving treatment may be an important future direction as the healthcare industry attempts to prioritize spending. What also requires further study is when and how to “step up” interventions for those who are non-responsive to behavioral maintenance interventions; thus future trials exploring adaptive techniques (e.g., Sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trials; SMARTs; http://methodology.psu.edu/ra/adap-inter/research) are needed.

Our study has limitations. First, the study did not collect follow-up information on Phase 1 participants who did not lose 4 kg or more, thus our results are directly applicable only to those who are able to successfully lose this amount of weight. Second, because of limited resources, we did not collect dietary and physical activity measures in Phase 3 and cannot comment on behavioral mediators as we did in Phase 2 (26). Third, given financial and logistical considerations, we were unable to collect prospective measures of cardiovascular and other medical outcomes. Finally, the trial's sample size precluded us from addressing the impact of extending PC in race and gender subgroups.

WLM also has numerous strengths. It is the longest trial that tested strategies to sustain newly achieved weight loss, and it enrolled a large proportion of African-American participants, a population at disproportionate risk for obesity and its consequences. Moreover, despite the long duration of Phase 3, follow-up was excellent (83% attended final data collection visits), and sophisticated procedures for dealing with missing data were employed. These factors contribute to the high internal validity of the study and potential generalizability of findings.

In conclusion, after initial weight loss of at least 4 kg followed by 30 months of brief monthly counseling primarily by telephone, continuation of the counseling intervention did not provide significant additional benefit over the next 30 months. Nonetheless, after 5 years, those initially assigned to this intervention had better long-term weight loss than those who were in the SD group and received no weight loss maintenance intervention. Regardless of treatment condition, weight regain was most substantial in the first year, continued at a slower rate in the second year, and largely flattened by the third year.

Acknowledgments

Funding agencies: Sponsored by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants 5-U01 HL68734, 5-U01 HL68676, 5-U01 HL68790, 5-U01 HL68920, 5-UO1 HL68955, and 5RC1HL099437.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Four of the study authors (JWC, LJA, GJJ, and ATD) have a financial relationship with Healthways, Inc., a company with whom we partnered for the POWER Trial (Appel, NEJM, 2012), which occurred after the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial was complete. This relationship presents no conflicts of interest with the organization that sponsored the research (NIH). VHM has a financial relationship with Naturally Slim, LLC, and this relationship presents no conflict of interest. All other authors declared no conflict of interest.

Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifer NCT00054925.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;131:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE) JAMA. 1998;279:839–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollis JF, Gullion CM, Stevens VJ, et al. Weight loss during the intensive intervention phase of the weight-loss maintenance trial. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butryn ML, Webb V, Wadden TA. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34:841–859. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLean PS, Wing RR, Davidson T, et al. NIH working group report: innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:7–15. doi: 10.1002/oby.20967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turk MW, Yang K, Hravnak M, Sereika SM, Ewing LJ, Burke LE. Randomized clinical trials of weight loss maintenance: a review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;24:58–80. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317471.58048.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dombrowski SU, Knittle K, Avenell A, Araujo-Soares V, Sniehotta FF. Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g2646. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Middleton KM, Patidar SM, Perri MG. The impact of extended care on the long-term maintenance of weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13:509–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, Usman Ali M, Raina P, Sherifali D. Strategies for weight maintenance in adult populations treated for overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E47–E54. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perri MG, Nezu AM, Patti ET, McCann KL. Effect of length of treatment on weight loss. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:450–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brantley P, Appel L, Hollis J, et al. Design considerations and rationale of a multi-center trial to sustain weight loss: the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial. Clin Trials. 2008;5:546–556. doi: 10.1177/1740774508096315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol Methods. 2001;6:330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klem ML, Wing RR, Lang W, McGuire MT, Hill JO. Does weight loss maintenance become easier over time? Obes Res. 2000;8:438–444. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:74–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, et al. Extended-care programs for weight management in rural communities: the treatment of obesity in under-served rural settings (TOURS) randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2347–2354. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1959–1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wadden TA, Webb VL, Moran CH, Bailer BA. Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation. 2012;125:1157–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wadden TA, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, et al. Four-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with long-term success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1987–1998. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coughlin JW, Gullion CM, Brantley PJ, et al. Behavioral mediators of treatment effects in the weight loss maintenance trial. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:369–381. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9517-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]