Abstract

Background

Gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter through activation of GABA receptors. Volatile anesthetics activate type A (GABAA) receptors resulting in inhibition of synaptic transmission. Lung epithelial cells have been recently found to express GABAA receptors that exert anti-inflammatory properties. We hypothesized that the volatile anesthetic sevoflurane (SEVO) attenuates lung inflammation through activation of lung epithelial GABAA receptors.

Methods

Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized with SEVO or ketamine/xylazine (KX). Acute lung inflammation was induced by intratracheal instillation of endotoxin, followed by mechanical ventilation for 4 h at a tidal volume of 15 mL/kg without positive end-expiratory pressure (two-hit lung injury model). To examine the specific effects of GABA, healthy human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) were challenged with endotoxin in the presence and absence of GABA with and without addition of the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin.

Results

Anesthesia with SEVO improved oxygenation and reduced pulmonary cytokine responses compared to KX. This phenomenon was associated with increased expression of the π subunit of GABAA receptors and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). The endotoxin-induced cytokine release from BEAS-2B cells was attenuated by the treatment with GABA, which was reversed by the administration of picrotoxin.

Conclusion

Anesthesia with SEVO suppresses pulmonary inflammation thus protects the lung from the two-hit injury. The anti-inflammatory effect of SEVO is likely due to activation of pulmonary GABAA signaling pathways.

Keywords: volatile anesthetics, mechanical ventilation, inflammation

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a major challenge in critical illness that is associated with high mortality [1]. The majority of patients suffering from ALI require mechanical ventilation for life support [2, 3]. However, mechanical ventilation per se bears the risk of inducing and worsening pulmonary dysfunction described as ventilator induced lung injury (VILI) [4]. An important approach to manage patients with ALI is to reduce pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses that may have played an important role inducing multiple distal organ dysfunction in the context of VILI [1, 2].

Low tidal volume ventilation has been considered as a protective ventilator strategy [2], but it may not suit to all patients with respiratory failure [5]. Volatile anesthetics have been recently shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects in several experimental and clinical settings [6–8], which may be beneficial in the context of VILI. The use of sevoflurane (SEVO) can increase expression of IκB while decreasing NF-κB nuclear translocation following challenge with tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in human monocytes [8]. The administration of SEVO improved gas exchange and attenuated lung injury after endotracheal installation of endotoxin in rats [6]. Anesthesia with SEVO has been shown to decrease the production of inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 in lung lavage fluids and reduced postoperative adverse events in patients under thoracic surgery [7]. However, the mechanisms by which SEVO exerts the anti-inflammatory effects remain unclear.

It is known that volatile anesthetics such as SEVO and isoflurane activate type-A gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptor resulting in inhibition of synaptic transmission in neurons [9, 10]. GABA, synthesized from glutamate by decarboxylation via the enzymatic activity of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), produces fast synaptic inhibition in neurons through activating GABAA receptor, a GABA-gated anion channel. In addition to its conventional role in synaptic transmission, GABAA receptors also exert novel anti-inflammatory properties in the central nervous system [11] and in peripheral immune cells [12].

It is interesting that recent studies have demonstrated that GABAA receptors are also expressed in lung airway and alveolar epithelial cells [13–16]. However, their local role in response to inhalation of SEVO remains to be investigated in the context of ALI. We thus hypothesized that anesthesia with SEVO attenuates pulmonary inflammatory response through activation of GABAA receptor in lung epithelial cells. To test this hypothesis we examined the effects of SEVO on the expression of GABAA receptor and cytokine responses in a rat model of ALI, and the specific effects of GABA on cytokine responses in vitro in human lung epithelial cells.

Material and Methods

Anesthesia and mechanical ventilation

The study was approved by the institutional Animal Care Committee (ACC948) of St. Michael’s Hospital. Thirty-four Sprague-Dawley rats (250 – 350 g) were randomly assigned to receive anesthesia with either ketamine + xylazine (KX, n = 17) or sevoflurane (SEVO, n = 17). In the KX group, anesthesia was induced using 80 mg/kg ketamine and 8 mg/kg xylazine intraperitoneally, followed by continuous intravenous infusion of ketamine at 15 mg/kg/h and xylazine at 3 mg/kg/h. In the SEVO group, anesthesia was induced by 3.5 Vol.% SEVO in a closed chamber and maintained with 2.6 Vol.%. These doses of anesthetics were chosen based on pilot experiments targeting similar mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and comparable depth of anesthesia defined by no reaction to toe pinches prior to neuromuscular blockade. Tracheotomy was performed followed by intratracheal intubation with a 14G angiocatheter. Neuromuscular blockade was achieved by i.v. infusion of pancuronium at 0.5 mg/kg/h.

The initial ventilator settings were as follows by using a rodent ventilator (Harvard 683): inspired oxygen fraction (FIO2) of 0.40, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5 cmH2O, tidal volume (VT) of 6 mL/kg and respiratory rate (RR) adjusted to keep arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) between 35 and 45 mmHg. The right carotid artery was cannulated (0.58 mm ID polyethylene tube) for continuous blood pressure monitoring. Intravenous infusion of lactated ringer solution at 3 mL/kg/h was administered through the tail vein in all animals. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37°C ± 1°C using a heating blanket.

Two-hit model of ALI

All animals received intratracheal instillation of endotoxin at 5 mg/kg (LPS, Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5, Sigma Aldrich). Thirty minutes later, mechanical ventilation was switched to high VT at 15 mL/kg and PEEP = 0 cmH2O for 4 h.

Measurements

MAP was monitored in a real time fashion. Arterial blood gases (PaO2, PaCO2) were recorded hourly throughout the experiments.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed in the left lung by using cold normal saline upon completion of the experiments. The BAL fluid was centrifuged at 4°C and 1,200 g for 10 min and the supernatant was stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Lung wet/dry ratio (WD ratio) was obtained after excision of the right lung and drying at 60°C for 72h.

The concentrations of glucose and lactate in blood were measured (Radiometer ABL 700 blood gas analyzer) at the end of the study.

Levels of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and multiple cytokines including interleukin 1-β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1α) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were measured using species specific multiplex cytokine assays (Bio-Rad) as previously described [17].

Basal expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD, GAD65/67 antibody, Abcam, Inc, Cambridge, MA), and GABAA receptor (GABA A Receptor alpha 2 antibody, Abcam, Inc.) was detected by immunohistochemistry in rats sacrificed by cervical dislocation without undergoing the experimental protocol to serve as healthy controls. The methods have been previously described by the authors [15]. GAD expression was also assessed by Western blot (GAD65/67 antibody, Abcam, Inc.) analysis as previously described [15].

Cell culture and treatment

Human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B, ATTC) were cultured in full confluence and incubated with GABA (100 nM) alone or GABA + picrotoxin, a GABAA receptor antagonist (PTX, 50 nM) for 10 min, followed by stimulation with LPS at 100 ng/mL (Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5, Sigma Aldrich) for 4h. This dose of LPS has been previously used for induction of inflammatory responses [18].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. Student’s t-test for unpaired samples was used to compare differences among groups at time 0 and for post-mortem analysis. Repeated measurements over time were analyzed with two-way analysis of variance for repeated measurements and adjusted with the Bonferroni post-test. Statistical significance was considered if p < 0.05.

Results

Bodyweight were similar in all animals. The amount of fluid infused was not different in both groups (11.3 ± 0.7 mL in SEVO vs. 12.5 ± 1.4 mL in KX group). Although the glucose level was slightly higher in the SEVO than in the KX group (8.59 ± 0.57 mmol/L vs. 7.83 ± 0.18 mmol/L) the difference did not reach statistically significance. However, a lower level of lactate in blood was observed in the SEVO group than the KX group (2.26 ± 0.23 mmol/L vs. 3.35 ± 0.45 mmol/L, p < 0.05).

Hemodynamics and gas exchange

MAP and PaCO2 showed a similar time course in all animals (Figure 1A and 1B, respectively). PaO2 decreased significantly starting 2h after high Vt ventilation in the KX group as compared to the SEVO (Figure 1C). The decreased level of PaO2 was associated with an increase in lung wet/dry ration suggesting enhanced lung permeability in the KX group (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Mean arterial pressure, gas exchange and lung permeability.

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP); arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) in animals anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (KX) or sevoflurane (SEVO) over time. Lung wet/dry weight ratio was determined at the end of 4-h mechanical ventilation started 30 min after LPS administration. N=17 per group.

Pulmonary inflammatory response

The total leukocyte count in BALF was significant lower in the SEVO group compared to the KX group (0.85 ± 0.04 × 106 vs. 1.03 ± 0.05 × 106, p < 0.05). Although there was a trend of decrease in the percentage of polymorphonuclear cells out of the total leukocytes (55 ± 5% vs. 69 ± 6%), the difference did not reach statistically significance. Cytokine profile in BAL fluid showed decreased levels of TNF-α, MIP-1α, IL-1β, KC, MCP-1 and ICAM-1 under anesthesia with SEVO compared to that with KX (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Inflammatory mediator responses in BAL fluid.

Cytokine and ICAM-1 responses in animals anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (KX) or sevoflurane (SEVO). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was obtained at the end of 4-h mechanical ventilation started 30 min after LPS intratracheal administration. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1α); interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β); keratinocyte growth factor (KC); monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). N=17 per group.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry showed a basal expression of GAD and GABAAR alpha unit colocalized with lung epithelium stained with surfactant protein C of healthy control rats (Figure 3A). Western blot assay showed a higher protein level of GAD in the SEVO group than in the KX group (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Lung expression of GAD and GABAAR receptor.

A. Immunohistochemistry staining for the epithelial marker surfactant protein C (green), and GAD (red), GABAAR (red) and their overlay (orange) in healthy rat lungs. B. Western blot for detection of GAD in animals anesthetized with KX or SEVO at the end of 4-h mechanical ventilation started 30 min after LPS intratracheal administration. Average expression of GAD over β-actin was from 5 experiments.

In vitro BEAS-2B cell experiments

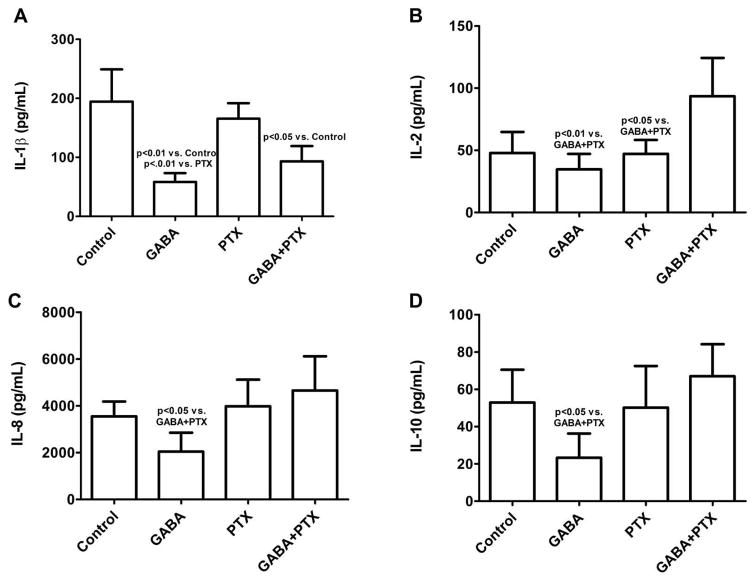

To investigate the specific effects of GABA in lung epithelial cells, human BEAS-2B cells were stimulated with LPS followed by treatment with GABA, PTX or GABA+PTX. We first confirmed that the dose of PTX used did not induce cytotoxicity as reflected by a constant LDH level before and after PTX administration [19], thus cell viability was no affected (data not shown). IL-1β was significantly reduced with GABA and GABA+PTX compared to Control and PTX alone group (Figure 4A). IL-2 was significantly decreased with GABA and PTX compared to GABA+PTX (Figure 4B). The concentrations of IL-8 and IL-10 decreased significantly with GABA, which was reserved by administration of PTX (Figure 4C and 4D, respectively).

Figure 4. Cytokine responses in BEAS-2B cells.

Concentration of cytokines measured in cell culture supernatants of human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) stimulated with LPS (Control) followed by incubation with gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), picrotoxin (PTX) or GABA+PTX for 8h. N = 5 experiments per group.

Discussion

We demonstrate that anesthesia with SEVO improves oxygenation and reduced pulmonary cytokine responses associated with increased expression of GABAA as compared to anesthesia with KX. These results suggest that the activation of GABAA receptors may play a role in the lung protective effect seen with SEVO.

An established two-hit model was chosen for its clinical relevance that primary lung inflammation/injury was followed by mechanical ventilation as a treatment [6]. Since a single drug of either ketamine or xylazine is not recommended, a regime of the combination is commonly used for animal anesthesia [20]. We examined two regimes of anesthesia by choosing SEVO and KX in the present study. To avoid possible interference and/or crossover effects between the SEVO and KX, the same anesthetic regime was used for both induction and maintenance. The two anesthetic regimes are functioning through distinct mechanisms of action that would help understand the possible signaling pathways responsible for their effects. SEVO acts mainly via agonistic effects on GABAA receptors. Ketamine interacts mainly with the NMDA-subtype glutamate receptor but at high, fully anesthetic level doses, it binds to opioid μ receptors and sigma receptors[21–23]. In comparison with SEVO, ketamine has minor effects by selectively acting on alpha6 and delta subunits of GABA receptors [22]. A majority of literature suggested that ketamine exerts antagonistic action at the GABAA-receptor complex [24–26]. In particular, ketamine has been reported to decrease the GAD67 isoform [27]. Our results are in agreement with these previous studies [24] [25–27]. It is noted that subanesthetic doses of ketamine was reportedly to inhibit tonic convulsions induced by the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline, and the latter antagonized ketamine anesthesia. However, the suggested agonistic effects of ketamine on GABAA was not examined directly in the study [28]. Xylazine is a clonidine analoque acting on presynaptic and postsynaptic receptors of the central and peripheral nervous systems as an α2-adrenergic agonist that is used primarily for sedation, aesthesia, analgesia and muscle relaxation in animal models [29]. Similar drugs such as clonidine and dexmedetomidine are increasingly used in clinical anesthesia and critical care [30]. The different pharmacological actions of the anesthetics used in this study may explain their distinct anti-inflammatory properties. In addition, paralysis was applied by administration of a given dose of pancuronium in all animals to reach synchrony between the animals and the ventilator in order to minimize signal to noise ratio and to enhance reproducibility of the experiments. It is therefore that the paralysis was part of the anesthesia regimes used in the present study.

Various inflammatory mediators including the cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, chemokines and ICAM-1 have been shown to act as effector molecules in the disruption of the epithelial and endothelial barrier during mechanical ventilation [31, 32]. We observe that the administration of SEVO attenuated the production of the inflammatory mediators in the lung and thus reduced lung permeability. Our results are in agreement with other studies showing anti-inflammatory effects of volatile anesthetics in a variety of in vivo and in vitro models. In an ischemia-reperfusion model of acute kidney injury, Lee et al. [33] reported direct anti-inflammatory and anti-necrotic effects of SEVO by activation of prosurvival kinases and increase in de-novo synthesis of heat shock protein 70. Boost et al. [8] demonstrated that isoflurane, acting also on GABAA receptors [34], attenuates the release of IL-8 and heme oxygenase 1 in human monocytic THP-1 cells in vitro through a mechanism by which the volatile anesthetic stabilizes the NF-κB inhibitory pathway.

IL-10 was originally discovered as the cytokine synthesis inhibiting factor based on its biological activity. It down-regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, MHC class II antigens, and co-stimulatory molecules by upregulation of itself. In the present study, the administration of GABA attenuated the LPS-induced production of IL-1β and IL-10 in BEAS-2B cells. This phenomenon is consistent with previous reports showing that concentrations of IL-1β and IL-10 increased in response to LPS challenge to counterbalance the pro- and anti-inflammatory responses [35, 36].

A recent study by Faller and colleagues [37] who reported in a mouse model of VILI by using a tidal volume of 12 mL/kg for 6 hours that the administration of the volatile anesthetic isoflurane resulted in a reduction in lung damage, inflammation and stress protein expression. Our data are consistent with their observation despite that we use a two hit model of ALI followed mechanical ventilation under the anesthesia with SEVO. Taken together, our and the previous study [37] support the concept that volatile anesthetics exert anti-inflammatory effects protecting the lung from injury.

Volatile anesthetics produce anesthetic action primarily by binding to GABAA receptor in neurons of the central nervous system (CNS) [15]. Specifically, SEVO activates GABAA receptor in the CNS resulting in an inhibition of neuronal activities [9, 15]. We have previously discovered the existence of GAD and GABA receptors in human airway epithelial cells [15], and other investigators identified GABA receptors in alveolar epithelial type II cells [14]. In an ongoing study, we observed that volatile anesthetics including SEVO also enhance GABAA receptor -mediated anion current in pulmonary epithelial cells. In the present study, we further confirmed the presence of GAD and GABAA receptor both in rat airway and alveolar epithelial cells. We also demonstrate that anesthesia with SEVO results in an increase in expression of GAD and GABAA receptor in the lung compared with KX. We speculate that an increase in GAD expression after SEVO administration may be due to a positive feedback mechanism as a result of the binding between SEVO and GABAA receptors.

The concentrations of cytokines were lower and the GAD expression was higher in the SEVO group than in the KX group in vivo conditions. These observations suggest that SEVO exerts anti-inflammatory properties partially by upregulation of GABA receptors. This concept was further supported by the in vitro lung epithelial cell studies where LPS induced-cytokine responses were attenuated in the presence of GABA, which was reversed by the administration of picrotoxin. Furthermore, it has been reported that an increase in surface levels of GABAA receptors requires the activity of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase C [38]. This is in accord with a recent study reporting that a mechanism by which isoflurane reduced VILI was through increasing phosphorylation of Akt protein, since the inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling prior to mechanical ventilation completely reversed the lung-protective effects of isoflurane in mice [37].

It is worthy note that anesthesia with SEVO or KX may result in hyperglycemia in rats [39, 40]. Clinical and experimental data suggest that hyperglycemia is protective against the development of ALI/ARDS [41]. We observe that the blood glucose level was higher in the SEVO than in the KX groups although the difference did not reach statistically significant. However, whether a different effect on glycemia between SEVO and KX might provide an additional pathway by which SEVO exerts a protective effect remains to be further investigated.

There are several limitations in the study, 1) The experimental double-hit model used in this study may not reflect the complex clinical scenario seen in patients with ALI/ARDS. 2) The involvement of GABAA receptor was the focus of the study, whether mechanisms other than GABAA receptor are also responsible in the protective effects of SEVO remains to be elucidated. 3) The study design compares the modulation of pulmonary inflammatory responses during mechanical ventilation by two different anesthesia regimens, it is impossible to draw conclusion whether the difference is due to the protective effects of one or the detrimental effects of the other single agent. 4) We focused the investigation on SEVO in the present study, further studies using other volatile (i.e., desflurane or isoflurane) or intravenous (i.e., propofol or midazolame) anesthetics are warranted.

In summary, we demonstrate that anesthesia with sevoflurane can improve oxygenation and reduce pulmonary cytokine responses as compared to ketamine/xylazine. The protective effects of sevoflurane appeared to be associated with its agonistic effects at GABAA receptors.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grants to WYL, AS and HZ, Ontario Thoracic Society (OTS) Grant-in-Aid and McLaughlin Foundation to HZ. SF was supported by the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. PS was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG SP 1222/3-1). PS is a recipient of the University of Toronto Eli Lilly Critical Care Fellowship Award.

The authors are indebted to Julie Khang, BSc for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Phua J, Badia JR, Adhikari NK, Friedrich JO, Fowler RA, Singh JM, Scales DC, Stather DR, Li A, Jones A, Gattas DJ, Hallett D, Tomlinson G, Stewart TE, Ferguson ND. Has mortality from acute respiratory distress syndrome decreased over time?: A systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:220–227. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-722OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome N. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brun-Buisson C, Minelli C, Bertolini G, Brazzi L, Pimentel J, Lewandowski K, Bion J, Romand J, Villar J, Thorsteinsson A, Damas P, Armaganidis A, Lemaire F for the ASG. Epidemiology and outcome of acute lung injury in European intensive care units. Results from the ALIVE study. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:51–61. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tremblay L, Valenza F, Ribeiro SP, Li J, Slutsky AS. Injurious ventilatory strategies increase cytokines and c-fos m-RNA expression in an isolated rat lung model 4. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:944–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI119259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhotra A. Low-tidal-volume ventilation in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1113–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct074213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voigtsberger S, Lachmann RA, Leutert AC, Schlapfer M, Booy C, Reyes L, Urner M, Schild J, Schimmer RC, Beck-Schimmer B. Sevoflurane ameliorates gas exchange and attenuates lung damage in experimental lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1238–1248. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bdf857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Conno E, Steurer MP, Wittlinger M, Zalunardo MP, Weder W, Schneiter D, Schimmer RC, Klaghofer R, Neff TA, Schmid ER, Spahn DR, Z’Graggen BR, Urner M, Beck-Schimmer B. Anesthetic-induced improvement of the inflammatory response to one-lung ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1316–1326. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a10731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boost KA, Leipold T, Scheiermann P, Hoegl S, Sadik CD, Hofstetter C, Zwissler B. Sevoflurane and isoflurane decrease TNF-alpha-induced gene expression in human monocytic THP-1 cells: potential role of intracellular IkappaBalpha regulation. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:665–671. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirota K, Roth SH. Sevoflurane modulates both GABAA and GABAB receptors in area CA1 of rat hippocampus. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:60–65. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sebel LE, Richardson JE, Singh SP, Bell SV, Jenkins A. Additive effects of sevoflurane and propofol on gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor function. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1176–1183. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhat R, Axtell R, Mitra A, Miranda M, Lock C, Tsien RW, Steinman L. Inhibitory role for GABA in autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2580–2585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915139107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duthey B, Hubner A, Diehl S, Boehncke S, Pfeffer J, Boehncke WH. Anti-inflammatory effects of the GABA(B) receptor agonist baclofen in allergic contact dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:661–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin N, Kolliputi N, Gou D, Weng T, Liu L. A novel function of ionotropic gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors involving alveolar fluid homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36012–36020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin N, Narasaraju T, Kolliputi N, Chen J, Liu L. Differential expression of GABAA receptor pi subunit in cultured rat alveolar epithelial cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;321:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiang YY, Wang S, Liu M, Hirota JA, Li J, Ju W, Fan Y, Kelly MM, Ye B, Orser B, O’Byrne PM, Inman MD, Yang X, Lu WY. A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med. 2007;13:862–867. doi: 10.1038/nm1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuta K, Osawa Y, Mizuta F, Xu D, Emala CW. Functional expression of GABAB receptors in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:296–304. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0414OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voglis S, Quinn K, Tullis E, Liu M, Henriques M, Zubrinich C, Penuelas O, Chan H, Silverman F, Cherepanov V, Orzech N, Khine AA, Cantin A, Slutsky AS, Downey GP, Zhang H. Human neutrophil peptides and phagocytic deficiency in bronchiectatic lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:159–166. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1250OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, Kim YK, Govindarajan A, Baba A, Binnie M, Marco Ranieri V, Liu M, Slutsky AS. Effect of adrenoreceptors on endotoxin-induced cytokines and lipid peroxidation in lung explants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1703–1710. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9903068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Racher AJ, Looby D, Griffiths JB. Use of lactate dehydrogenase release to assess changes in culture viability. Cytotechnology. 1990;3:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00365494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green CJ, Knight J, Precious S, Simpkin S. Ketamine alone and combined with diazepam or xylazine in laboratory animals: a 10 year experience. Lab Anim. 1981;15:163–170. doi: 10.1258/002367781780959107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narita M, Yoshizawa K, Aoki K, Takagi M, Miyatake M, Suzuki T. A putative sigma1 receptor antagonist NE-100 attenuates the discriminative stimulus effects of ketamine in rats. Addict Biol. 2001;6:373–376. doi: 10.1080/13556210020077091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hevers W, Hadley SH, Luddens H, Amin J. Ketamine, but not phencyclidine, selectively modulates cerebellar GABA(A) receptors containing alpha6 and delta subunits. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5383–5393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5443-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirota K, Sikand KS, Lambert DG. Interaction of ketamine with mu2 opioid receptors in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. J Anesth. 1999;13:107–109. doi: 10.1007/s005400050035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kounenis G, Koutsoviti-Papadopoulou M, Elezoglou V. Ketamine may modify intestinal motility by acting at GABAA-receptor complex; an in vitro study on the guinea pig intestine. Pharmacol Res. 1995;31:337–340. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(95)80086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vutskits L, Gascon E, Potter G, Tassonyi E, Kiss JZ. Low concentrations of ketamine initiate dendritic atrophy of differentiated GABAergic neurons in culture. Toxicology. 2007;234:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonner JM, Zhang Y, Stabernack C, Abaigar W, Xing Y, Laster MJ. GABA(A) receptor blockade antagonizes the immobilizing action of propofol but not ketamine or isoflurane in a dose-related manner. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:706–712. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000048821.23225.3A. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Behrens MM, Lisman JE. Prolonged exposure to NMDAR antagonist suppresses inhibitory synaptic transmission in prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:959–965. doi: 10.1152/jn.00079.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irifune M, Sato T, Kamata Y, Nishikawa T, Dohi T, Kawahara M. Evidence for GABA(A) receptor agonistic properties of ketamine: convulsive and anesthetic behavioral models in mice. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:230–236. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200007000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Villar R, Toutain PL, Alvinerie M, Ruckebusch Y. The pharmacokinetics of xylazine hydrochloride: an interspecific study. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1981;4:87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.1981.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riker RR, Shehabi Y, Bokesch PM, Ceraso D, Wisemandle W, Koura F, Whitten P, Margolis BD, Byrne DW, Ely EW, Rocha MG. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:489–499. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruewer M, Luegering A, Kucharzik T, Parkos CA, Madara JL, Hopkins AM, Nusrat A. Proinflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2003;171:6164–6172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi H, Fleming NW, Serikov VB. Contact activation via ICAM-1 induces changes in airway epithelial permeability in vitro. Immunol Invest. 2007;36:59–72. doi: 10.1080/08820130600745703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee HT, Kim M, Jan M, Emala CW. Anti-inflammatory and antinecrotic effects of the volatile anesthetic sevoflurane in kidney proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F67–78. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00412.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jia F, Yue M, Chandra D, Homanics GE, Goldstein PA, Harrison NL. Isoflurane is a potent modulator of extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors in the thalamus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:1127–1135. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.134569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erickson MA, Banks WA. Cytokine and chemokine responses in serum and brain after single and repeated injections of lipopolysaccharide: multiplex quantification with path analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:1637–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ward JL, Harting MT, Cox CS, Jr, Mercer DW. Effects of ketamine on endotoxin and traumatic brain injury induced cytokine production in the rat. J Trauma. 2011;70:1471–1479. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821c38bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faller S, Strosing KM, Ryter SW, Buerkle H, Loop T, Schmidt R, Hoetzel A. The Volatile Anesthetic Isoflurane Prevents Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury via Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Signaling in Mice. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:747–756. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824762f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porcher C, Hatchett C, Longbottom RE, McAinch K, Sihra TS, Moss SJ, Thomson AM, Jovanovic JN. Positive feedback regulation between gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA(A)) receptor signaling and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release in developing neurons. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21667–21677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaufman DA. Time-dependent behavioral recovery after sepsis in rats. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:576. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1369-0. author reply 577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitamura T, Ogawa M, Kawamura G, Sato K, Yamada Y. The effects of sevoflurane and propofol on glucose metabolism under aerobic conditions in fed rats. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1479–1485. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b8554a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Honiden S, Gong MN. Diabetes, insulin, and development of acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2455–2464. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a0fea5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]