Abstract

Animal bodies are mainly composed of hydrogels — polymer networks infiltrated with water. Most biological hydrogels are mechanically flexible yet robust, and they accommodate transportations (e.g., convection and diffusion) and reactions of various essential substances for life – endowing living bodies with exquisite functions such as sensing and responding, self-healing, self-reinforcing and self-regulating et al. To harness hydrogels’ unique properties and functions, intensive efforts have been devoted to developing various biomimetic structures and devices based on hydrogels. Examples include hydrogel valves for flow control in microfluidics[1], adaptive micro lenses activated by stimuli-responsive hydrogels[2], color-tunable colloidal crystals from hydrogel particles[3, 4], complex micro patterns switched by hydrogel-actuated nanostructures[5], responsive buckled hydrogel surfaces[6], and griping and self-walking structures based on hydrogels[7–9]. Entering the era of mobile health or mHealth, as unprecedented amounts of electronic devices are being integrated with human body[10–14], hydrogels with similar physiological and mechanical properties as human tissues represent ideal matrix/coating materials for electronics and devices to achieve long-term effective bio-integrations[15–17]. However, owing to the weak and brittle nature of common synthetic hydrogels, existing hydrogel electronics and devices mostly suffer from the limitation of low mechanical robustness and low stretchability. On the other hand, while hydrogels with extraordinary mechanical properties, or so-called tough hydrogels, have been recently developed[18–22], it is still challenging to fabricate tough hydrogels into stretchable electronics and devices capable of novel functions. The design of robust, stretchable and biocompatible hydrogel electronics and devices represents a critical challenge in the emerging field of soft materials, electronics and devices.

Here, we report a set of new materials and methods to integrate stretchable conductors, rigid electronic components, and drug-delivery channels and reservoirs into biocompatible and tough hydrogel matrices that contain significant amounts of water (e.g., 70 ~ 95 wt %). The resultant hydrogel-based electronics and devices are mechanically robust, highly stretchable, biocompatible, and capable of multiple novel functions. We show that the design of robust hydrogel-solid interfaces is particularly important to the functionality and reliability of stretchable hydrogel electronics and devices. Programmable delivery and sustained release of mock drugs can be achieved by controlling the flow of mock drug solutions through selected channels and reservoirs in hydrogel matrices at both undeformed and highly stretched states. We further demonstrate novel applications including a stretchable LED array encapsulated in biocompatible hydrogel matrix, and a smart hydrogel wound dresser that is highly stretchable, transparent, and capable of sensing temperatures at different locations on the skin and sustained release of various mock drugs to specific locations accordingly.

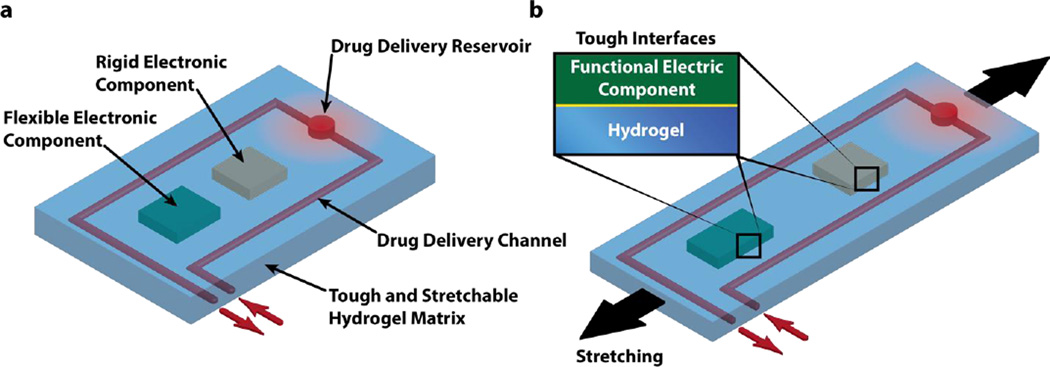

Figure 1 gives a generic illustration of the design of stretchable hydrogel electronics and devices. A biocompatible, highly stretchable and robust hydrogel provide a soft and wet matrix for electronics and devices – drastically different from dry elastomer/polymer matrices for conventional stretchable electronics. Functional electronic components such as conductors, microchips, transducers, resistors, capacitors are embedded inside or attached on the surface of the hydrogel (Fig. 1a). The electronic components may be covered (or partially covered) by an insulating layer such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) to maintain their normal functions in wet environments of hydrogels. Drug-delivery channels and reservoirs are further patterned in the hydrogel matrix, such that when drug solutions flow through the channels and/or into the reservoirs, they can diffuse out of the hydrogel to give programmable and sustained release of drugs (Fig. 1a). As the hydrogel electronic device is stretched, flexible electronic components can deform together with the device but rigid components will maintain their undeformed shapes, which requires larger deformation of hydrogel around rigid components than others (Fig. 1b). Therefore, in order to maintain reliability and functionality of the device, the hydrogel matrix and the interfaces between hydrogel and functional components need to be tough and robust under large deformation.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the design of stretchable hydrogel electronics and devices.

a) Functional electronic components such as conductors, microchips, transducers, resistors, and capacitors are embedded inside or attached on the surface of the hydrogel. Drug-delivery channels and reservoirs are patterned in the hydrogel matrix, and they can diffuse drugs out of the hydrogel to give programmable and sustained release of drugs. b) As the hydrogel electronic device is stretched, flexible electronic components can deform together with the device but rigid components will maintain their undeformed shapes, which requires robust interfaces between electronic components and hydrogel matrix.

The design of tough hydrogels relies on a combination of long-chain polymer networks that are highly stretchable and other components (such as other polymer networks) that can dissipate significant mechanical energy under deformation[23–25]. In Table 1, we provide a set of polymer candidates for the long-chain networks including Polyacrylamide (PAAm) and Polyethylene glycol (PEG) that are covalently crosslinked by N,N-Methylenebisacrylamide (BIS) and Diacrylate (DA) respectively, and the dissipative networks including alginate, hyaluronan and chitosan that are reversibly crosslinked by calcium sulfate, iron (III) chloride, sodium tripolyphosphate respectively. Table 1 further gives the optimal concentrations for each combination of networks and crosslinkers that can lead to tough hydrogels[19, 26,27]. The biocompatibility has been validated for hydrogels with individual polymer network of PAAm, PEG, alginate, hyaluronan or chitosan[28], therefore, the mixture of these individual polymer network are potentially biocompatible. Notably, the biocompatibility of specific combinations of PAAm-alginate and PEG-alginate tough hydrogels are reported in previous literature[26, 29]. Since the biocompatible PAAm-alginate hydrogel gives the highest stretch ability (~ 21 times) and fracture toughness (~ 9,000 Jm−2) among all candidates in Table 1, we choose PAAm-alginate as the hydrogel matrix for stretchable electronics and devices in the current study. It should be noted that using other tough hydrogels in Table 1 as matrices may have other benefits in applications; for example, the PEG-alginate and PEG-hyaluronan hydrogel matrices can allow encapsulation of viable cells in hydrogel electronics and devices[26, 30].

Table 1.

Compositions of a set of tough hydrogels with elastic network and dissipative networks[19, 26, 27] (Note that while the water concentration in hydrogels at as-prepared state ranges from 73 wt.% to 85%, it may increase up to 95% after swelling in water.)

| Dissipative Polymer Networks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | HA | Chitosan | ||

|

Elastic Polymer Networks |

PAAm | 12 wt. % AAm, 0.017 wt. % MBAA, 2 wt. % alginate, CaSO4(20 mM concentration in gel) |

18 wt. % AAm, 0.026 wt. % MBAA, 2 wt. % HA, Iron (III) chloride (3 mM concentration in gel) |

24 wt. % AAm, 0.034 wt. % MBAA, 2 wt. % chitosan, TPP (3 mM concentration in gel) |

| PEGDA | 20 wt. % PEGDA, 2.5 wt. % alginate, CaSO4(20 mM concentration in gel) |

20 wt. % PEGDA, 2 wt. % HA, Iron (III) chloride (3 mM concentration in gel) |

20 wt. % PEGDA, 2 wt. % Chitosan, TPP (3 mM concentration in gel) |

|

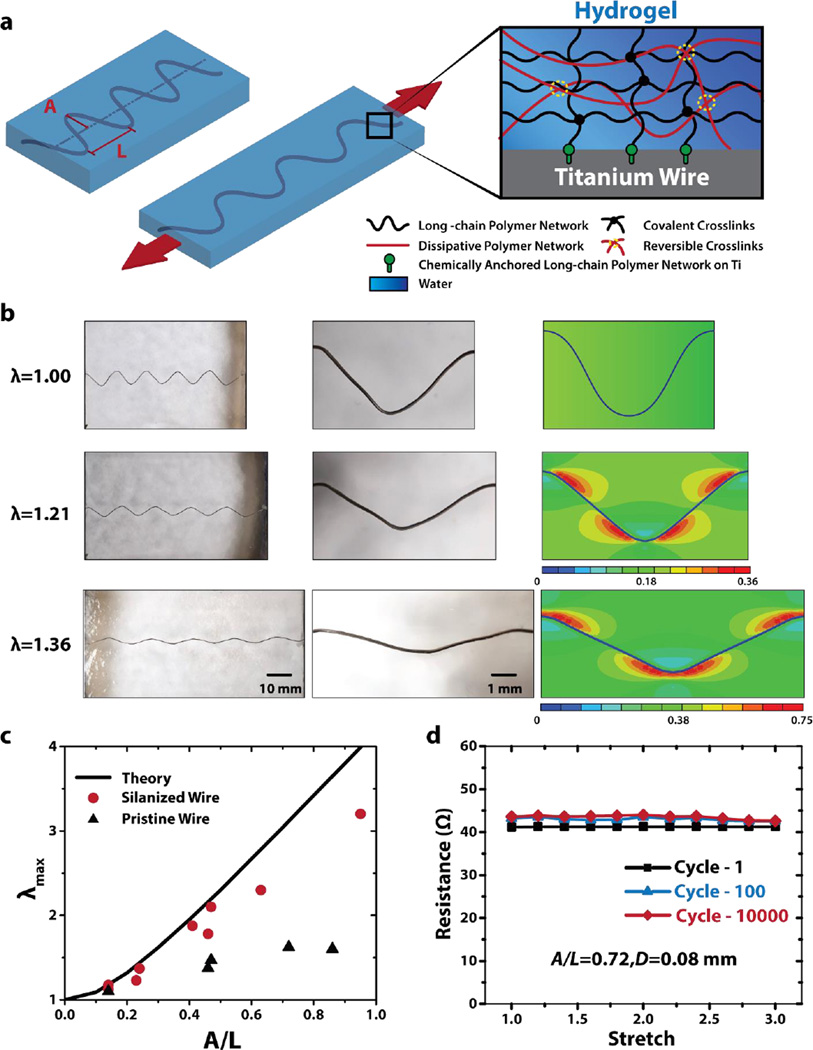

Now that a stretchable and robust hydrogel matrix has been determined, we will discuss methods to integrate various functional components including conductive wires, rigid chips, and drug-delivery channels and reservoirs into the hydrogel matrix. Given the high mechanical robustness and biocompatibility of titanium, we choose titanium wires (Unkamen Supplies, Diameters D: 0.08 mm ~ 0.2 mm) as the candidate for conductive components in hydrogel electronics and devices. Figure S2 illustrates the procedure to encapsulate titanium wires into hydrogel matrix to form transparent, stretchable and robust hydrogel conductors. In brief, the surface of titanium wire was functionalized with silane 3-(Trimethoxysilyl) Propyl Methacrylate (TMSPMA)[27] (See experimental section for details on silane functionalization.) The titanium wire was then deformed into a sinusoidal shape with amplitude A and wavelength L (Fig. 2a), either through the constraint of a mold (for relatively thin wires, e.g. diameter 0.08 mm) or plastic deformation (for relatively thick wires, e.g. diameter 0.2 mm)[11, 31–34]. Thereafter, pre-gel solution was casted around the deformed titanium wire and cured in a mold that determines the shape and dimensions of the hydrogel matrix. During the curing process, the PAAm long-chain network in the hydrogel was covalently anchored on the titanium wire (Fig. S1), giving extremely tough interface between hydrogel matrix and conductive wire (i.e., interfacial toughness over 1500 Jm−2)[27]. Figure 2b demonstrates a hydrogel conductor with A/L=0.23 for the encapsulated titanium wire. It can be seen that, except for the region of the wire, the hydrogel conductor is transparent – clearly showing the background of a white paper. As the hydrogel conductor is deformed to different stretches λ (defined as deformed length over undeformed length), the sinusoidal-shaped wire decreases its amplitude and increases its wavelength, enabling high stretchability of the hydrogel conductor (Fig. 2b). Because the hydrogel is much more compliant than titanium wire (shear modulus 10 kPa vs. 40 GPa) and highly stretchable, it can accommodate the shape change of the titanium wire without fracture or delamination (Fig. 2b). Finite-element model (using software, ABAQUS) of the hydrogel conductor indicates that the maximum principle strain in hydrogel matrix occurs around stationary points of the wavy interface between hydrogel and titanium wire (Fig. 2b) (See supplementary material for details of the finite-element model). Once the titanium wire becomes fully straight, the hydrogel conductor cannot be further stretched without inducing plastic deformation or failure of the wire[35] (See Fig. S4). Therefore, the theoretical limit of the stretch on the hydrogel conductor can be calculated as

| (1) |

Figure 2. Integration of wavy titanium wires in tough hydrogel matrix.

a) Schematic illustration of the transparent, highly stretchable and robust hydrogel electronic (DC) conductor. Long-chain polymer network of tough hydrogel matrix is chemically anchored onto silanized titanium surface via covalent crosslinks. b) The wavy wire can be highly stretched together with hydrogel matrix without fracture or debonding due to robust adhesion between wire and hydrogel matrix. Finite-element simulation shows maximum principal strain of the hydrogel matrix. c) The calculated λmax as a function of A/L in comparison with experimentally measured maximum stretches in hydrogel conductors that contain titanium wires with and without silanized surfaces. d) The hydrogel conductor (A/L=0.72, diameter D=0.08mm) can sustain multiple cycles (i.e., 10,000) of high stretch (i.e., 3), while maintaining constant resistance.

In Fig. 2c, we plot the calculated λmax as a function of A/L, and compare the theoretical limit with the maximum stretches measured in hydrogel conductors that contain titanium wires with and without silanized surfaces. Since the silanized titanium has a robust interface with the tough hydrogel matrix[27], the corresponding hydrogel conductor can reach very high maximum stretches (e.g., >2), only slightly lower than the theoretical limits (Fig. 2c). For example, Video S1 demonstrates a hydrogel conductor that contains a silanized titanium wire (A/L=0.32) being stretched to the theoretical limit of stretch λmax ≈ 1.58. On the other hand, the hydrogel conductor with pristine titanium wire fails quickly under moderate stretch (Fig. S3), due to the debonding between titanium wire and hydrogel matrix. Therefore, the measured maximum stretch for hydrogel conductor with pristine titanium wire is much lower than the value of silanized wire with the same A/L and the theoretical limit (Fig. 2c). These results prove that robust hydrogel-conductive-wire interfaces are critical to the reliability of stretchable hydrogel conductors. In addition, as shown on Fig. 2d, the hydrogel conductor can sustain multiple cycles (i.e., 10,000) of high stretch (i.e., 3), while maintaining constant total measured resistance. While high concentrations of salt solutions[36] and hydrogels that contain such solutions[37] have been used as transparent ionic conductors, the current work presents a simple method to fabricate transparent, highly stretchable and robust electronic conductors based on biocompatible hydrogels.

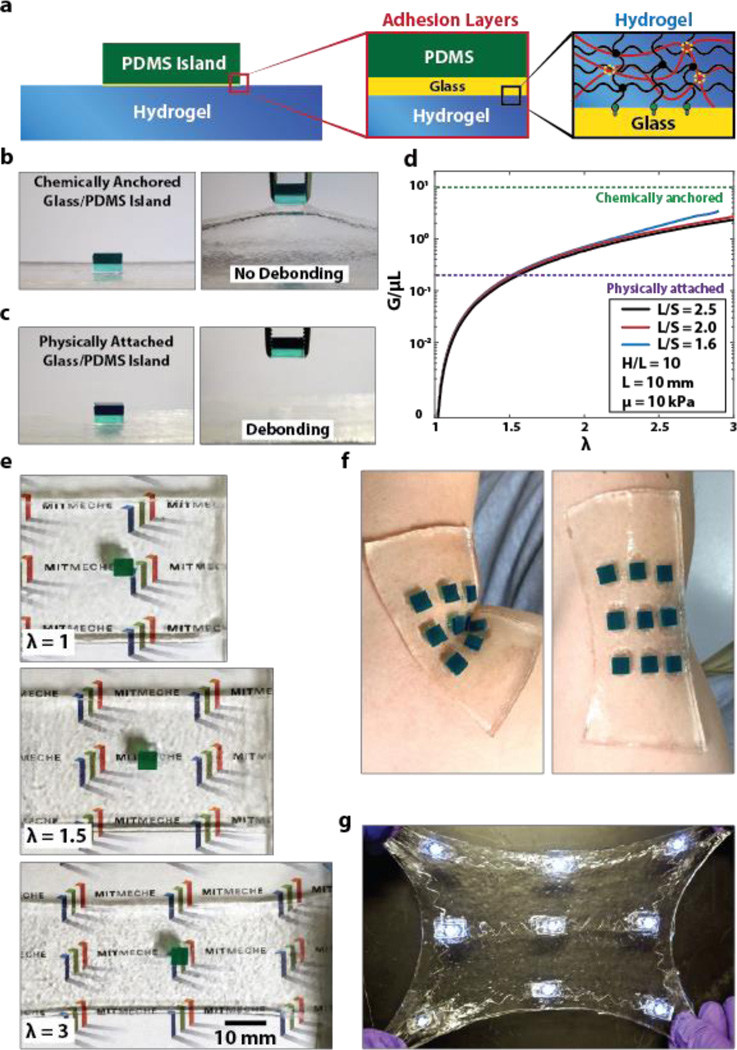

We next discuss the method to integrate relatively rigid components such as rigid chips into the hydrogel matrix. We will use chips made of PDMS (DowCorning Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit) to represent the rigid electronic components, since these electronic components are likely to be covered by PDMS for insulation from wet environment of the hydrogel matrix. However, it is challenging to form robust adhesion between hydrogels and PDMS due to its intrinsic oxygen permeation and radical scavenging nature[38]. Although a few methods were proposed by imparting the hydrophilicity of PDMS and coating PDMS with hydrophilic materials as hydrogels, the reported adhesion between hydrogels and PDMS may be not strong enough to sustain extremely large deformation[39]. Here, we used glass slides as intermediate layers to form tough bonding between chips and hydrogel matrix. Figure S5 illustrates the procedure to attach rigid electronic components on the surface of (or embed them inside) hydrogel matrix. One side of the glass slide and the PDMS chip were exposed to oxygen plasma for 2 min, and physically contacted each other right after plasma treatment to form siloxane covalent linkage between the glass slide and PDMS chip. Thereafter, the exposed surface of the attached glass slide was again exposed to oxygen plasma for 5 min and covered by TMSPMA aqueous solution for 2 hours. To adhere the PDMS chips on the surface of hydrogel matrix, we fabricated acrylic mold with laser-cut holes to host the PDMS-glass assemblies. Each assembly was put into a hole in the mold with functionalized glass side up, and then the pre-gel solution was poured into the mold. During the curing process, the PAAm long-chain network in the hydrogel was covalently anchored on glass slide, which gives high interfacial toughness over 1500 Jm−2[27] (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b and Video S2 demonstrates a PDMS chip bonded on the surface of hydrogel using silanized glass slide. It can be seen that the chip does not detach from the hydrogel, even when it is pulled by a tweezer that significantly deforms the hydrogel matrix. On the other hand, if the chip with pristine glass is physically attached on hydrogel, it can be easily detached by the tweezer, indicating the importance of functionalized and robust interfaces in hydrogel electronics (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Integration of rigid chips on the surface of (or inside) tough hydrogel matrix.

a) Schematic illustration of a rigid PDMS chip bonded on the surface of hydrogel. Glass slide is used to form stable and robust adhesion layer between PDMS chip and tough hydrogel. Oxygen plasma treated PDMS and glass slide surface are covalently bonded through siloxane bond, while silanization of the glass slide gives tough covalent bonding to hydrogel. b) Chemically anchored Glass/PDMS chip is robustly bonded on hydrogel matrix even when pulled by a tweezer. c) Physically attached Glass/PDMS chip is easily debonded from hydrogel matrix. d) Chemically anchored Glass/PDMS chip doesn’t debond from hydrogel matrix even under high stretch (up to 3 times) due to robust adhesion between adhesion layers. e) The calculated G/µL from the finite-element model is plotted as functions of λ and S/L. The typical values of interfacial toughness between chips and hydrogels with and without silanized interfaces are also given for comparison (1000 J/m2 and 20 J/m2 respectively). f) A sheet of hydrogel (thickness ~ 1.5 mm) with multiple patterned chips can conformably attach to different regions of human body and survive deformation due to body movements. g) A hydrogel electronic device that encapsulates an array of LED lights connected by stretchable silanized titanium wire. The device is transparent, and robust under multiple cycles of high stretch.

To predict whether a chip will debond from hydrogel matrix under deformation, we develop a plane-strain island-substrate model using finite-element software, ABAQUS[40]. (See supplementary material for details of the finite-element model.) The energy release rate G for initiating interfacial cracks between the chip and hydrogel substrate can be expressed as

| (2) |

where μ is the shear modulus of the hydrogel modeled as a neo-Hookean material, L the width of the chip, λ the applied stretch, S center-to-center distance between two adjacent chips, H thickness of undeformed hydrogel substrate, and f(•) a non-dimensional function. Since G/μL is a monotonic increasing function of H / L (Fig. S7), we focus on the case with infinitely deep substrate (i.e., H / L = ∞) to be conservative in the design. The calculated G / μL from the finite-element model is plotted in Fig. 3d as functions of λ and S / L The typical values of interfacial toughness between chips and hydrogels with and without silanized interfaces are also given in Fig. 3d for comparison. When the energy release rate reaches the interfacial toughness, cracks initiate on the interface inducing failure of the hydrogel device. The model shows that the chip-hydrogel structure with silanized interface can sustain very high stretch without debonding, but the structure without silanized interface will debond at relative low stretch (e.g., λ = 1.5). Figure 3e further demonstrate that the chip bonded with silanized interface does not detach from hydrogel matrix under high stretch (e.g., λ = 3). Since the hydrogel is soft, wet and biocompatible, a sheet of hydrogel (thickness ~ 1.5 mm) with multiple patterned chips can conformably attach to different regions of human body (e.g., the elbow in Fig. 3f). Movement of the body part deforms the hydrogel but will not debond the chips.

In addition to bonding on hydrogel surfaces, the rigid chips can also be encapsulated inside hydrogel matrices. In this case, tough interfaces between the chips and hydrogel can be achieved via multiple intermediate glass slides (Fig. S5). For example, Figure 3g and Video S3 illustrate a hydrogel electronic device that encapsulates an array of LED lights connected by stretchable wires (See Fig. S8 for details on fabrication). This new design of hydrogel-encapsulated LED array is soft, biocompatible, transparent, and robust under large deformations such as high stretch (Fig. 3g) and conformal deformation on human body (Video S3).

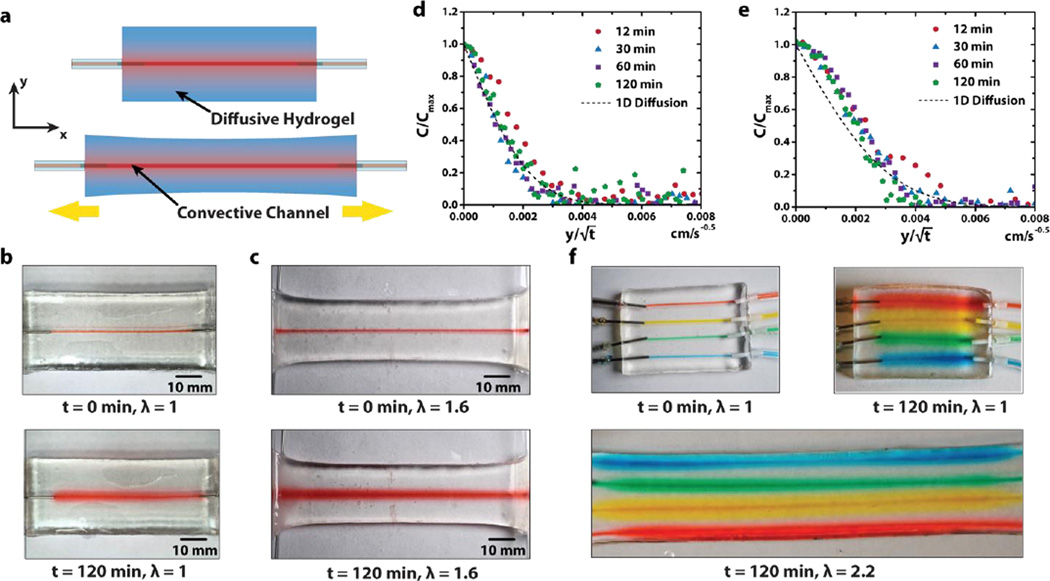

One unique advantage of hydrogels over dry polymers as matrices for stretchable electronics and devices is the capability of drug diffusion in hydrogels[28, 41]. In the current design, we pattern drug-delivery channels and reservoirs in the hydrogel matrix. Drug solutions can be fed to the channels and reservoirs from external sources via controlled convections (Fig. 4a). If the hydrogel matrix is in contact with human body, the drug solutions can diffuse from the channels and reservoirs out of the hydrogel matrix and maintain a sustained release at controlled locations in/on the body. Fig. 4b demonstrates the diffusion of a mock drug, 2% aqueous solution of a red food dye (McCormick), from a drug-release channel in a hydrogel matrix over time (See Table S1 for detailed ingredients of the mock drug). To simplify the analysis, we set the diameter of the drug-delivery channel close to the thickness of the hydrogel sheet, and seal the hydrogel sheet with silicone oil. This leads to approximately one-dimensional diffusion of the drug solution in the hydrogel sheet governed by

| (3) |

where C is the concentration of the drug at a point in the hydrogel, t the current time, y vertical position of the point in hydrogel at deformed state, and D the diffusion coefficient of the drug in the hydrogel. Since drug concentration on the wall of the channel (i.e., y = 0) is fixed to be C0 over time, Eq. (3) can be solved as

| (4) |

where eff(•) is the error function. We plot the measured values of C / C0 at different times and different locations in the hydrogel as functions of in Fig. 4d, and fit the diffusion coefficient of the drug in the hydrogel to be 1.5×10−10m2/s. In addition, when the hydrogel sheet is stretched (e.g., λ = 1.6 in Fig. 4c), it still accommodates drug diffusion without burst leakage, owing to the high toughness and stretchability of the hydrogel. The drug diffusion coefficient in the stretched hydrogel (Fig. 4e) is 3 × 10−10m2/s, higher than that in undeformed hydrogel, possibly due to the increase of mesh size in stretched hydrogel. In Fig. 4f, we further demonstrate that multiple drugs represented by different food dyes (See Table S1 for detailed ingredients) with different colors can be released simultaneously in the hydrogel device under multiple cycles of high stretches.

Figure 4. Integration of drug-delivery channels in tough hydrogel matrix.

a) Schematic illustration of diffusion of drug solution inside hydrogel from the drug-delivery channel. b) Experimental snapshots of drug diffusion in the undeformed hydrogel. c) Experimental snapshots of drug diffusion in the deformed hydrogel. d) Normalized one-dimensional diffusion of mock drug inside undeformed hydrogel channel. e) Normalized one-dimensional diffusion of mock drug inside deformed (λ = 1.6) hydrogel channel. f) Experimental snapshots of the diffusion of multiple mock drugs in a hydrogel matrix under high stretches.

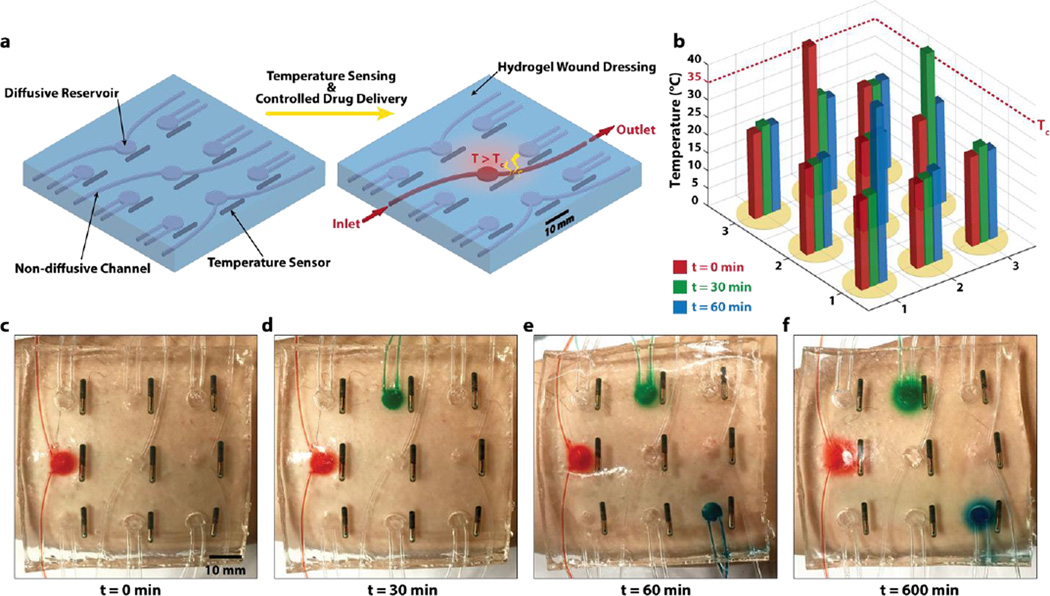

To further demonstrate novel functions of stretchable and biocompatible hydrogel electronics and devices, we fabricate a smart wound dressing that combines temperature sensors, drug delivery channels and reservoirs patterned into a stretchable and transparent tough hydrogel sheet (Fig. 5). Figure S9 illustrates the procedure to pattern temperature sensors (24PetWatch), non-diffusive drug-delivery channels (made of plastic tubes), and diffusive drug reservoirs in the hydrogel matrix. (See experimental methods for details of the procedure.) As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the temperature sensors were patterned into a 3 by 3 matrix with a drug-delivery reservoir next to each sensor. The smart wound dressing can give programmable and sustained deliveries of different drugs at various locations over human skin according to the temperatures measured at those locations (Fig. 5). For a conceptual demonstration, as a sensor detects that the temperature at a location increases above a threshold (e.g., 35°C) at a certain time, a drug solution can be manually delivered through the non-diffusive drug-delivery channel to the corresponding drug reservoir and then diffuse out of the hydrogel matrix in a controlled and sustained manner (Fig. 5a). The same procedure can be repeated according to the measurements from different temperature sensors over time (Fig. 5a–c). Figure 5c–f and Video S4 illustrates the controlled delivery and sustained releases of various drugs at different locations according to the temperatures measured at different times.

Figure 5. A smart wound dressing based on stretchable and biocompatible hydrogel device.

a) The temperature sensors are patterned into a 3 by 3 matrix with a drug-delivery reservoir next to each of them. The smart wound dressing can give programmable and sustained deliveries of different drugs at various locations over human skin according to the temperatures measured at those locations. b) The temperatures at different locations on the skin are measured via wireless temperature sensor over time. c–f) When the temperature at a location goes above a certain level (e.g., Tc = 35 °C), a mock drugs is injected through non-diffusive channels into the corresponding reservoir to diffuse out over time. Sustained releases of various drugs are achieved at different locations according to the temperatures measured at different times.

In summary, we report a set of novel materials and methods to integrate various electronic components and drug-delivery channels and reservoirs into tough hydrogel matrix —achieving stretchable, robust and biocompatible hydrogel electronics and devices. The compliant hydrogel matrix can accommodate both deformable (e.g., wavy wires and channels) and rigid (e.g., silicon chips) components embedded in or attached on it, even when the hydrogel electronics and devices are highly deformed. Experiments and numerical simulation show that the interfaces between hydrogel matrix and functional components are often subjected to high stresses, due to the mechanical mismatch. Surface functionalization (e.g., coating and silanization) of the functional components can give tough covalent bonding to the hydrogel, which is critical to functionality and reliability of hydrogel electronics and devices. We further demonstrate novel applications of hydrogel electronics and devices including a soft, wet, transparent and stretchable LED array, and a smart wound dresser capable of sensing temperatures of various locations on the skin, delivering different drugs to these locations, and subsequently maintaining sustained releases of drugs.

Experimental Methods

Synthesis of tough hydrogels

We followed the previous reported protocol for synthesis of PAAm-alginate tough hydrogel[19, 26, 27]. A precursor solution was prepared by mixing 4.1 mL 4.8 wt. % alginate (Sigma, A2033) and 5.5 mL 18.7 wt. % acrylamide (Sigma, A8887). We added 377 µL 0.2 g/100ml N,N-methylenebisacrylamide (Sigma, 146072) as the crosslinker for polyacrylamide and 102 µL 0.2 M ammonium persulphate (Sigma, 248614) as an initiator for polyacrylamide. After degassing the precursor solution in a vacuum chamber, we added 200 µL 1 M calcium sulphate (Sigma, C3771) as the ionic crosslinker for alginate and 8.2 µL N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (Sigma, T7024-50M) as the crosslinking accelerator for acrylamide. Thereafter, the precursor solution was poured into an acrylic mold and was subjected to ultraviolet light for 60 minutes with 8 W power and 254 nm wavelength to cure the hydrogel.

The PAAm-hyaluronic acid tough hydrogel was synthesized by mixing 10 mL of degassed precursor solution (18 wt. % AAm, 2 wt. % HA, 0.026 wt. % MBAA and 0.06 wt. % APS) with 60 µL of iron (III) chloride solution (0.05 M) and TEMED (0.0025 the weight of AAm). The PAAm-chitosan tough hydrogel was synthesized by mixing 10 mL of degassed precursor solution (24 wt. % AAm, 2 wt. % chitosan, 1 wt. % acetic acid, 0.034 wt. % MBAA and 0.084 wt. % APS) with 60 µL of TPP solution (0.05 M) and TEMED (0.0025 the weight of AAm). The PEGDA-alginate tough hydrogel was synthesized by mixing 10 mL of a degassed precursor solution (20 wt. % PEGDA and 2.5 wt. % sodium alginate) with calcium sulfate slurry (0.068 the weight of sodium alginate) and Irgacure 2959 (0.0018 the weight of PEGDA). The PEGDA-hyaluronan tough hydrogel was synthesized by mixing 10 mL of a degassed precursor solution (20 wt. % PEGDA and 2 wt. % HA) with 60 µL of iron chloride solution (0.05 M) and Irgacure 2959 (0.0018 the weight of PEGDA). The PEGDA-chitosan tough hydrogel was synthesized by mixing 10 mL of a degassed precursor solution (20 wt. % PEGDA, 2 wt. % chitosan and 1 wt. % acetic acid) with 60 µL of TPP (0.05 M) and Irgacure 2959 (0.0018 the weight of PEGDA). The curing procedure was identical to the PAAm-alginate tough hydrogel.

Silanization and grafting of glass slide and titanium wire

We followed the previous reported protocol for bonding of hydrogels to glass and titanium[27]. The surfaces of glass and titanium were functionalized by grafting functional silane TMSPMA. Solid substrates were thoroughly cleaned with aceton, ethanol and deionized water in order, and completely dried before the next step. Cleaned substrates were treated by oxygen plasma (30 W with 200 mTorr pressure, Harrick Plasma PDC-001) for 5 min. Right after the plasma treatment, substrate surface was covered with 5 mL of the silane solution (100 mL deionized water, 10 µL of acetic acid with pH 3.5 and 2 wt. % of TMSPMA) and incubated for 2 hours in the room temperature. Substrates were washed with ethanol and completely dried. Functionalized substrates were stored in low humidity condition before used for experiments.

During oxygen plasma treatment of the solids, oxide layers on the surfaces of the solids (silicon oxide on glass and titanium oxide on titanium) were reacted into hydrophilic hydroxyl groups by oxygen radicals produced by oxygen plasma. These hydroxyl groups on the oxide layer can readily form hydrogen bonds with silanes in the functionalization solution generating a self-assembled layer of silanes on the oxide layers[42]. Notably, methyl groups in TMSPMA are readily hydroxylated in acidic aqueous environment and form silanes. These hydrogen bonds between surface oxides and silanes become chemically stable siloxane bonds with removal of water forming strongly grafted TMSPMA onto oxide layers on various solids[43].

Grafted TMSPMA has methacrylate terminal group which can form covalent linkage with acrylate groups in acrylamide under radical crosslinking process, generating chemically anchored long-chain polymer network onto various solid surfaces[44]. Since the long-chain polymer networks in hydrogels are chemically anchored onto solid surfaces via strong and stable covalent bonds, the interfaces can achieve relatively high intrinsic work of adhesion than physically attached hydrogels. The silane functionalization chemistry is summarized in Fig. S1.

Adhesion between PDMS and glass slide

PDMS chips were fabricated by mixing resin and crosslinker with 10:1 weight ratio (DowCorning Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit), and cure it for 5 hours at 90 °C. PDMS chips were covalently bonded onto glass slide by introducing both surface with oxygen plasma for 2 min and physically contact both surfaces. It is well known that oxygen plasma generates hydroxyl groups on both glass and PDMS surface, and these Si-OH groups form covalent siloxane bond at their physical contact[45].

Fabrication of sinusoidal titanium wire

Plastically deformable titanium wire (Unkamen Supplies, Diameters: 0.08 mm ~ 0.2 mm) was formed into wavy shape by squeezing linear wire in between wavy acrylic mold. Since titanium wire is plastically deformable, the amplitude and period of sinusoidal shape were controlled by using different geometry of molds (Fig. S2a).

The measurement of stretchability and resistivity of hydrogel with titanium wire encapsulated

The stretchability of the tough hydrogel with titanium wire encapsulated was measured using universal machine (2 kN load cell; Zwick / Roell Z2.5). Before curing the pre-gel solution, sinusoid titanium wire was placed inside the mold measuring 70mm × 25mm × 3mm (Fig. S2b). The resultant sample was stretched at 1/min using universal testing machine (Fig. S2c), which gives the representative stress-stretch curves as shown in Fig. S3a. For the hydrogel with pristine titanium wire encapsulated, the detachment (Fig. S3b) between titanium wire and hydrogel occurs, which gives the maximum stretch λmax. While for the hydrogel with silanized titanium wire encapsulated, no detachment can be observed till the titanium wire is stretched to the locking stretch, which gives the maximum stretch λmax. To fully understand the locking stretch of the sample with chemically anchored titanium wire, we calculated the theoretical locking stretch of a sinusoidal titanium wire. One segment in the titanium wire can be expressed as (see Fig. 2a). Since the arc length of a curve is , the theoretical locking stretch of a sinusoidal titanium wire can be expressed as Eq. (1). In addition to the measurement of stretchability, the electrical resistance was measured using the same test set-up by multimeter.

Preparation and operation of smart wound dressing

The smart wound dressing sample was fabricated by making channels and reservoirs using both patterned acrylic mold and sacrificial gelatin[46]. Figure S9 shows the schematic illustration of fabrication procedures. A patterned acrylic mold was made using laser cut machine (Epilog Mini/Helix) and thereafter the PAAm-alginate precursor solution was poured into the mold. After the sample was fully cured in UV oven for 60 minutes with 8 W power and 254 nm wavelength, heated gelatin solution (Knox, 10 wt. % at 70 °C) was infused into the shaped reservoirs with the diameter of 8mm and EVA tubings with outside diameter of 1.52 mm and wall thickness of 0.51 mm (McMaster, 1883T1) was placed in the shaped channels. The sample with both gelatin disks and EVA tubings was stored in refrigerator (5 °C) for 5 min. Then the temperature sensors (24PetWatch) were placed beside the reservoirs and the sample was again covered with precursor solution, encapsulated with gelatin disks, EVA tubings and temperature sensors. The whole sample was further cured in room temperature for 30 min. After the second curing, the entire wound dressing was placed at oven (70 °C) for 10 min. Liquefied gelatin was wash away from the tough hydrogel matrix by flowing deionized water multiple times through channels and reservoirs. During the operation of the smart wound dressing, a heat gun was applied to induce concentrated heat to increase local temperature of the wound dressing, and a drug solution was pumped into the corresponding drug reservoir once the temperature at a location increased over the critical value.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by ONR (No. N00014-14-1-0528), MIT Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, and NSF (No. CMMI-1253495). H. Y. acknowledges the financial support from Samsung Scholarship. H. K. acknowledges the financial support from Samsung. X. Z. acknowledges the supports from NIH (No. UH3TR000505) and MIT Materials Research Science and Engineering Center. S. L. and X. Z. acknowledge the help from Zhifei Ge and Prof. Cullen Buie on diffusion test.

Reference

- 1.Beebe DJ, Moore JS, Bauer JM, Yu Q, Liu RH, Devadoss C, Jo BH. Nature. 2000;404:588. doi: 10.1038/35007047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong L, Agarwal AK, Beebe DJ, Jiang HR. Nature. 2006;442:551. doi: 10.1038/nature05024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debord JD, Eustis S, Debord SB, Lofye MT, Lyon LA. Advanced Materials. 2002;14:658. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwayama Y, Yamanaka J, Takiguchi Y, Takasaka M, Ito K, Shinohara T, Sawada T, Yonese M. Langmuir. 2003;19:977. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidorenko A, Krupenkin T, Taylor A, Fratzl P, Aizenberg J. Science. 2007;315:487. doi: 10.1126/science.1135516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Hanna JA, Byun M, Santangelo CD, Hayward RC. Science. 2012;335:1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1215309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda S, Hara Y, Sakai T, Yoshida R, Hashimoto S. Advanced Materials. 2007;19:3480. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morales D, Palleau E, Dickey MD, Velev OD. Soft matter. 2014;10:1337. doi: 10.1039/c3sm51921j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palleau E, Morales D, Dickey MD, Velev OD. Nature communications. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong J-W, Shin G, Park SI, Yu KJ, Xu L, Rogers JA. Neuron. 2015;86:175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers JA, Someya T, Huang Y. Science. 2010;327:1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1182383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer S, Bauer-Gogonea S, Graz I, Kaltenbrunner M, Keplinger C, Schwödiauer R. Advanced Materials. 2014;26:149. doi: 10.1002/adma.201303349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammock ML, Chortos A, Tee BCK, Tok JBH, Bao Z. Advanced Materials. 2013;25:5997. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu N. The Bridge on Frontiers of Engineering. 2013;43:31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan L, Yu G, Zhai D, Lee HR, Zhao W, Liu N, Wang H, Tee BC-K, Shi Y, Cui Y. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:9287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202636109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu C, Duan Z, Yuan P, Li Y, Su Y, Zhang X, Pan Y, Dai LL, Nuzzo RG, Huang Y. Advanced Materials. 2013;25:1541. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren H, Panhuis M in het. Synthetic Metals. 2015;206:61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong JP, Katsuyama Y, Kurokawa T, Osada Y. Advanced Materials. 2003;15:1155. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun J-Y, Zhao X, Illeperuma WRK, Chaudhuri O, Oh KH, Mooney DJ, Vlassak JJ, Suo Z. Nature. 2012;489:133. doi: 10.1038/nature11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun TL, Kurokawa T, Kuroda S, Ihsan AB, Akasaki T, Sato K, Haque MA, Nakajima T, Gong JP. Nat Mater. 2013;12:932. doi: 10.1038/nmat3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens L, Calvert P, Wallace GG. Soft Matter. 2013;9:3009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren H, Gately RD, O'Brien P, Gorkin R. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics. 2014;52:864. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong JP. Soft Matter. 2010;6:2583. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao X. Soft Matter. 2014;10:672. doi: 10.1039/C3SM52272E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang T, Lin S, Yuk H, Zhao X. Extreme Mechanics Letters. 2015;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong S, Sycks D, Chan HF, Lin S, Lopez GP, Guilak F, Leong KW, Zhao X. Advanced Materials. 2015;27:4035. doi: 10.1002/adma.201501099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuk H, Zhang T, Lin S, Parada GA, Zhao X. Nature Materials. 2015. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101:1869. doi: 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darnell MC, Sun J-Y, Mehta M, Johnson C, Arany PR, Suo Z, Mooney DJ. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8042. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan C, Liao L, Zhang C, Liu L. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2013;1:4251. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20600a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lv C, Yu H, Jiang H. Extreme Mechanics Letters. 2014;1:29. [Google Scholar]

- 32.He J, Nuzzo RG, Rogers J. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2015;103:619. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim D-H, Ahn J-H, Choi WM, Kim H-S, Kim T-H, Song J, Huang YY, Liu Z, Lu C, Rogers JA. Science. 2008;320:507. doi: 10.1126/science.1154367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahn J-H, Je JH. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2012;45:103001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang K-I, Chung HU, Xu S, Lee CH, Luan H, Jeong J, Cheng H, Kim G-T, Han SY, Lee JW, Kim J, Cho M, Miao F, Yang Y, Jung HN, Flavin M, Liu H, Kong GW, Yu KJ, Rhee SI, Chung J, Kim B, Kwak JW, Yun MH, Kim JY, Song YM, Paik U, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Rogers JA. Nat Commun. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q, Zhang L, Zhao X. Physical review letters. 2011;106:118301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.118301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keplinger C, Sun J-Y, Foo CC, Rothemund P, Whitesides GM, Suo Z. Science. 2013;341:984. doi: 10.1126/science.1240228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dendukuri D, Panda P, Haghgooie R, Kim JM, Hatton TA, Doyle PS. Macromolecules. 2008;41:8547. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cha C, Antoniadou E, Lee M, Jeong JH, Ahmed WW, Saif TA, Boppart SA, Kong H. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013;52:6949. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shivapooja P, Wang Q, Orihuela B, Rittschof D, López GP, Zhao X. Advanced Materials. 2013;25:1430. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. ADVANCED MATERIALS-DEERFIELD BEACH THEN WEINHEIM. 2006;18:1345. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dugas V, Chevalier Y. Journal of colloid and interface science. 2003;264:354. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9797(03)00552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida W, Castro RP, Jou J-D, Cohen Y. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2001;17:5882. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muir BV, Myung D, Knoll W, Frank CW. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:958. doi: 10.1021/am404361v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duffy DC, McDonald JC, Schueller OJ, Whitesides GM. Analytical chemistry. 1998;70:4974. doi: 10.1021/ac980656z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golden AP, Tien J. Lab on a Chip. 2007;7:720. doi: 10.1039/b618409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.