Abstract

Background

Acute leukemia represents 4% of cancer cases in the United States (US) annually. There are over 302,000 people living with acute and chronic leukemia in the US. Treatment has been shown to have both positive and negative effects on health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Objective

Examine psychometric properties of symptom and HRQOL instruments and to provide implications for the assessment in adults with acute leukemia relevant to clinical practice and future research.

Methods

Systematic literature search was conducted from 1990-2014 using electronic databases and manual searches. Psychometric studies were considered eligible for inclusion if 1) the psychometric paper was published using at least one HRQOL or symptom instrument and 2) adults with acute leukemia were included in the sample. Studies were excluded if the age groups were not adults, or if the instrument was in a language other than English.

Results

Review identified a total of 7 instruments (1 cancer generic HRQOL, 2 symptom-related, 3 HRQOL combined with symptom questions, and 1 disease- specific). The most commonly used instrument was the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30), followed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Fatigue (FACT-F).

Conclusions

An acute leukemia diagnosis can have a significant impact on HRQOL. Our recommendations include using both a HRQOL and symptom instrument to capture patient experiences during and after treatment.

Implications for Practice

The availability of comprehensive, valid and reliable HRQOL and symptom instruments to capture the experiences of adults with acute leukemia during and posttreatment is limited.

Keywords: Acute leukemia, acute leukemia survivors, health related quality of life, symptoms, instruments, psychometrics, cancer-related fatigue

Introduction

It is estimated that 54, 270 individuals in the Unites States (US) will be diagnosed with leukemia in 2015 and an estimated 24,450 will die from the disease.1 Of these new cases, 27,080 have acute lymphoblastic leukemia or acute myeloid leukemia, and 11, 910 will die with the disease, with the remaining being chronic leukemias1. Acute leukemia has a 5-year survival rate of 56% in the US.2 Newly diagnosed acute leukemia is usually treated in a specialized care center with an average stay of 4-6 weeks. It is common for patients to have fluctuating symptoms associated with the disease and its treatment such as myelosuppression, stomatitis, and nausea throughout their hospitalization.3,4

There is the potential to advance acute leukemia science by systematically reviewing symptoms that occur, solely or concurrently, during and after treatment to determine how health-related quality of life (HRQOL) changes over time. It is important to understand patient-reported symptoms and HRQOL of adults with acute leukemia to better address their physical and psychosocial needs. In Bryant et al,4 cancer related fatigue (CRF), depression, and anxiety were found to be the most prominent symptoms that interfered with HRQOL and activities of daily living. In that review, we found that acute leukemia and its treatment have a significant impact in all QOL domains; we concluded that there was a need for future studies focused on longitudinal research and increased minority representation4.

One common way of assessing symptoms and HRQOL is through self-reported instruments, measuring the outcomes at one or more points. These instruments vary in the symptoms and HRQOL domains measured, the length of the questionnaire, the wording of questions and their response options, the reference or recall period, and the level of psychometric evidence in support of the validity and reliability of the measure.

The majority of the measures are not leukemia specific, except for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu), which was recently developed in 2002.5

This review examined the psychometric properties of instruments used in acute leukemia research, and provides clinical and research relevant implications of symptom and HRQOL instruments used in adults with acute leukemia.

Methods

Search strategy

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines6, a systematic literature search was conducted by the first (ALB) and third (JSK) authors. The search was completed in August 2014. The electronic databases PubMed, PsychInfo, EMBASE, CINAHL, and HAPI were searched using the following text words and their combinations: leukemia or leukaemia and each individual instrument included in this study. In a previous acute leukemia literature review conducted by Bryant et al4, 20 instruments were identified: Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Distress Thermometer, Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30), Fatigue Visual Analog Scale (F-VAS), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Fatigue (FACT-F), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Spiritual (FACT-Sp), Functional Living Index-Cancer (FLIC), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital and Anxiety Scale (HADS), Life Ingredient Profile (LIP), Mental Adjustment to Cancer (MAC), the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI), Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale-Self report (PAIS-SR), Perceived Quality of Life (PQOL), Revised Piper Fatigue Scale (RPFS), Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQOL), and Short-Form-36 (SF-36). Fifteen instruments were removed from the initial review of 20 instruments due to not being clearly defined as a symptom or HRQOL domain, lack of testing to determine psychometric properties, or the sample did not specifically include adults with acute leukemia. The five remaining instruments were BFI7, FACT-F8, FACT-G9, MDASI10, and EORTC QLQ-C3011. Two additional instruments were added based on the search strategy: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An)8 and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu).5 The final analysis included 7 instruments.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if 1) the psychometric paper was published using at least one HRQOL or symptom instrument and 2) adults with acute leukemia were included in the sample. Studies were excluded if the age groups were not adults, or if the instrument was in a language other than English. Other exclusions included case reviews, summary reports, clinical reviews, and literature and systematic reviews.

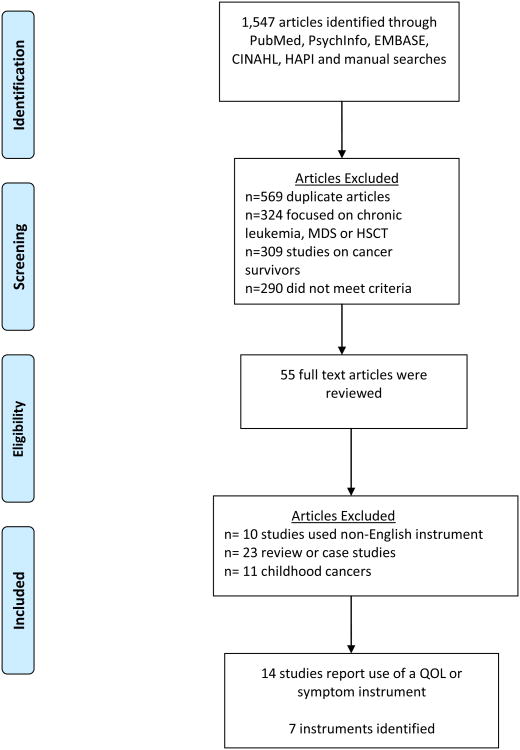

A total of 1,547 articles were identified through the 5 electronic databases and manual searches. Five hundred sixty-nine were duplicates articles, 324 were chronic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), 309 were about cancer survivors and not acute leukemia, and 290 did not meet the criteria and were removed after initial review. Fifty-five full text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 10 of those were excluded because the studies used non-English instruments, 23 were review or case studies, and 11 focused on childhood cancers. Fourteen studies reported use of a HRQOL and/or symptom instrument 7,12-24 (Figure 1). Seven instruments were identified based on inclusion criteria: 1) Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI)7, 2) European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30)11, 3) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An)8, 4) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Fatigue (FACT-F)8, 5) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G)9, 6) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu)5, and 7) M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI)10.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Data Extraction

Both generic and disease-specific HRQOL aspects of leukemia were identified in this review. In addition, the review also yielded symptom instruments which were either solely symptom focused or multidimensional with HRQOL domains. The psychometric properties, reliability and validity, of each instrument were extracted using the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust criteria.6 Reliability is “the degree to which an instrument is free from error” and validity is the “degree to which the instrument measures what it purports to measure”6(pg. 3).

Data Synthesis

The findings from the review are in narrative and table form. The different measures identified in this review and their complete description such as number of items, scoring, domains, scaling, reliability, validity, and numbers of studies are provided in Table 1. The number of items and measured domains of all instruments ranged from 10-47 and 5-15, respectively. Four instruments measured both symptom and HRQOL domains (FACT-An, FACT-F, FACT-Leu and EORTC QLQ-C30). The 14 studies identified in the review are described in Table 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of Instruments Used to Measure Symptoms and HRQOL in Adults with Acute Leukemia.

| Instrument | # of items | Domains Measured | Scale | Recall Period | Were acute leukemia patients included in sample? | Reliability | Validity | Language/Cultural Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI)7 | 10 items Higher score, more fatigue (intensity/interference) patients perceived |

Fatigue Intensity Average fatigue intensity Worst level of fatigue Least level of fatigue Fatigue interference with daily life (past week) |

0-11 Likert 0=no fatigue (or no interference) at all to 10=worst fatigue (or interference) one can imagine |

Past 24 hours | Yes n=17 (51%) acute leukemia |

IC: 0.96 Test-retest: Nor reported in original study |

Content Criterion related: concurrent Construct: Divergent |

Psychometrically and linguistically validated in 8 languages Chinese (simplified and traditional) English Filipino German Greek Japanese Korean Russian |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30)11 | 30 items Higher score poorer QOL |

Fatigue Nausea Pain Dyspnea Sleep Disturbance Appetite Loss Constipation Diarrhea Physical function Role function Social function Emotional function Cognitive Financial Impact Global QOL |

0-4 Likert 0=not at all to 4=very much |

Past Week | Yes n=113 (100%) acute leukemia |

Cronbach alpha: 0.54-0.89 Test-retest: Not reported in original study |

Content Criterion related: Concurrent Predictive Construct: Convergent Divergent Known group |

79 languages |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Anemia (FACT-An)8 | 47 items Higher the number, greater anemia symptoms |

Physical Well-being Social Well-being Emotional Well-being Functional Well-being Anemia related questions |

0-4 Likert 0=not at all to 4=very much |

Past 7 days | Yes n=3 (6%) acute leukemia |

IC: .96 Test retest: .96 |

Content Criterion-related: Concurrent Construct: Convergent Divergent Known group validity |

60 languages |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Fatigue (FACT-F)8 | 40 items Higher the number, increased fatigue |

Physical Well-being Social Well-being Emotional Well-being Functional Well-being Fatigue related questions |

0-4 Likert 0=not at all to 4=very much |

Past 7 days | Yes n=3 (6%) acute leukemia |

IC: .93-.95 Test retest: .90 |

Content Criterion-related Concurrent Construct Convergent Divergent Known group validity |

58 languages |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- General (FACT-G)9 | 27 items Higher the number, poorer QOL |

Physical Well-being Social/Family Well-being Emotional Well-being Functional Well-being |

0-4 Likert 0=not at all to 4=very much |

Past 7 days | Yes N=8% leukemia |

Internal consistency .69-.82 Test-retest reliability .82-.92 |

Content Criterion-related: Concurrent Construct: Convergent Divergent Known group validity |

60 languages |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Leukemia (FACT-Leu)5 | 42 items Higher the number, greater leukemia symptoms |

Physical Well-being Social Well-being Emotional Well-being Functional Well-being Leukemia related questions |

0-4 Likert 0=not at all to 4=very much |

Past 7 days | Yes N=35 (44%) acute leukemia |

Internal consistency .75-.96 Test-retest reliability .765-.890 |

Content Criterion-related: Concurrent Construct: Convergent Divergent Known Group Validity |

46 languages |

| M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI)10 | 13 items Higher the number, increase symptom distress |

General activity Mood Work Relations with others, Walking Enjoyment of life |

Symptom Severity 0=Not present to 10=As Bad as you can Imagine Symptom Interference 0=Did not interfere and 10=interfered completely |

Last 24 hours | Yes n=29 acute leukemia |

IC: 0.82-0.94 Test-retest: 0.83-0.84 |

Content Criterion-related: Concurrent Predictive Construct: Convergent Known group validity |

Psychometrically and linguistically validated in 9 languages Arabic Chinese (Simplified and traditional) English Filipino French Greek Japanese Korean Russian |

Table 2. Summary of the Studies using Symptoms and HRQOL Instruments in Adults with Acute Leukemia (n=14).

| Author Purpose |

Study Design | Sample Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Alibhai, Leach et al14 | Prospective, longitudinal | Total n=65; n=65 acute leukemia |

| Alibhai, Leach, Kermalli et al13 | Prospective, longitudinal | Total n=65; n=65 acute leukemia |

| Alibhai et al12 | Non-randomized, prospective exercise intervention | Total n=35; n=35 acute leukemia |

| Battaglini et al15 | Non-randomized exercise intervention | Total n=10; n=10 acute leukemia |

| Cella et al24 | Tool validation | Total n=29 (item generation), 79 (validation); acute and chronic leukemia |

| Efficace et al16 | Prospective, observational | Total n=119; mixed cancers |

| Jarden et al17 | Prospective exercise and health counseling trial | Total n=17; n=17 acute leukemia |

| Oliva et al20 | Prospective, observational | Total n=113; n=113 acute leukemia |

| Mendoza et al7 | Tool validation | Total n=595; n=68 acute leukemia |

| Mohamedali et al19 | Prospective, longitudinal cohort | Total n=103; n=103 acute leukemia |

| Pearce et al21 | Prospective, cross-sectional | Total n=150; mixed cancers |

| Persson et al22 | Prospective, longitudinal | Total n=16; mixed cancers |

| Shabbir et al18 | Non-randomized prospective exercise intervention | Total n=35; n=35 acute leukemia |

| Schumacher et al23 | Prospective, longitudinal | Total n=28; n=28 acute leukemia |

Validated HRQOL measures used in Adults with Acute Leukemia

A total of 7 instruments (1 cancer generic HRQOL, 2 symptom-related, 3 HRQOL combined with symptom questions, and 1 disease-specific) were identified and included in this review. The cancer generic HRQOL instrument was the FACT-G.9 The two symptom-related instruments included the BFI7 and MDASI10. The three HRQOL instruments with symptom questions included FACT-An8, FACT-F8, and EORTC-QLQ-C3011. The FACT-Leu was the only disease-specific instrument.5

Description of Symptom and HRQOL Instruments and their Psychometric Properties

The psychometric properties of the fourteen studies and their use of symptom and HRQOL instruments are presented in the Table 2. The symptom measure with the highest number of items was MDASI.10 The most commonly used HRQOL measure was the EORTC-QLQ-C30 measures (physical, role, social and emotional function, cognitive, financial impact, and global QOL).

The number of items and domains in the symptom instruments ranged from 1-13 and 1-6. The BFI recall period was in the “past 24 hours,”7 MDASI recall period was the “last 24 hours,”10 and FACT instruments were in the “last 7 days”5,8-9. All the HRQOL instruments reviewed in this study report overall internal consistency reliability in the range of .54-.96 and test-retest reliability ranging from .77-96. Content and convergent validity were reported for all measures.

Description of Identified Studies

The fourteen studies included in this review were of several types: one was a prospective, cross-sectional study, two were tool validation studies, two were prospective observational studies, four were exercise interventions, and five were prospective longitudinal studies. Ten of the studies included only patients with acute leukemia, one included patients with acute and chronic leukemia and the other three studies included patients of various cancer types. (Table 2). Stage of cancer treatment was not included because of the variety of cancer types and treatments patients were undergoing. The average number of patients in each of these studies was 104 (range 10-595). All studies were published between 1998-2012.

Discussion

This study reviewed the published psychometric literature and described 7 instruments that measured symptoms or HRQOL in adults with acute leukemia. There is no universally accepted definition of QOL/HRQOL, but various organizations and researchers have defined it as multidimensional in nature. In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO)25 defined QOL as “an individual's perception of their position in life, in the context of the culture and value systems in their life, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.”25 Cella's26 definition of HRQOL refers to the extent to which one's usual or expected physical, emotional, and social well-being are affected by a medical condition or its treatment, whereas Ferrell's QOL framework27 includes physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. Consideration of these QOL domains is necessary in understanding the impact of an acute leukemia treatment and the long term and late effects that accompany this diagnosis.

While using the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust guidelines28, we assessed the HRQOL instruments using the attributes and criteria that focus on reliability, validity, cultural and language adaptations. We did assess cultural and language adaptations and noted many of these instruments had been translated and adapted in several languages. One challenge faced by researchers and clinicians is use of reliable and valid measures during and after treatment are responsive to clinical changes. Measures that can capture change over time (i.e., an instruments “responsiveness” to change) are ideal and allows for comparisons between time points. There are two types of HRQOL measures used in this analysis. First, the generic cancer HRQOL measure, FACT-G, is able to measure these domains across different cancers. Few instruments are available that measure HRQOL domains specific to acute leukemia survivors, with one exception, the FACT-Leu. Surprisingly, the FACT-F measure was used more often in these studies than FACT-G or FACT-Leu. This may be associated with emerging data on the impact that cancer related fatigue (CRF) has on adults with acute leukemia during inpatient treatment12-15,17-18,29-30, and CRF being a persistent symptom during and after treatment.3-4,31 The FACT-G and EORTC-QLQ-C30 have been validated in a number of cancer groups with a variety of translations, compared to the FACT-Leu, which was only recently developed and validated.

Limitations of this review include focus on adults with acute leukemia without searching grey literature for additional studies such as dissertation abstracts and letters to the editors. We did not focus on chronic leukemias or other hematological cancers, which limits our generalizability to other cancers. However, a systematic methodologic approach using PRISMA was a strength of this review.

Conclusions

Acute leukemia researchers, clinicians, and oncology nurses need to have comprehensive data to explore clinical changes in their patients' symptom or HRQOL responses. Oncology nurses are at the frontline of caring for these patients and it is essential for them to be aware of instruments and tools used in acute leukemia research. Their use of these instruments will allow for early recognition and identification of common symptoms and/or HRQOL changes in these adults. There are certain domains of HRQOL that may be more prominent in acute leukemia survivors, such as increased symptoms and decreased functionality.4 To the authors' knowledge, this is the first review to explore the psychometric properties of instruments used with the acute leukemia adult population.

Our recommendations for clinical use and research are based on this review including a using both a HRQOL and symptom instrument to capture patient experiences during and after treatment. There are sound, reliable instruments that have been used in this population and we believe there are instruments that could adequately measure the patient's symptom and HRQOL experience throughout their illness trajectory. However, we question if these measures will be relevant over time with longer term survivors? The majority of measures have been tested in patients within 2 years of treatment; researchers lack data to support use of these measures in longer term survivors (>5 years or longer). Survivorship needs of these patients may need to be re-evaluated after 2 years since the late and long term effects may differ in each cancer population.

The HRQOL instruments vary in domains but the FACT-Leu has both general and specific leukemia questions. None of the current studies identified used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a promising new system designed to validly and reliably measure HRQOL domains in multiple populations; however no studies to date have examined the psychometric properties of PROMIS measures in acute adult leukemia. This review provides an overall synopsis of previous symptom and HRQOL literature in the acute leukemia population.

Acknowledgments

Support has been provided from the Cancer Care Quality Training Program Postdoctoral Fellowship (5R25CA116339) and NCI 5K12CA120780-07 (Bryant) and Doctoral Scholarship in Cancer Nursing Renewal (DSCNR-13-276-03) from the American Cancer Society, the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32NR013456 and the Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholar Program (Walton).

Footnotes

Dr. Reeve has a conflict of interest with Patient Reported Outcomes and Behavioral Evidence (PROBE) Advisory Board.

No other conflicts of interest from the remaining authors.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. 2015 Retrieved February 23, 2015 at http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/allcancerfactsfigures/index.

- 2.National Cancer Institute. SEER Stat Facts Sheets: Leukemia. 2015 Retrieved February 23, 2015 from http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/leuks.html.

- 3.Albrecht T. Physiologic and psychological symptoms experienced by adults with acute leukemia: an integrative literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(3):286–95. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.286-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant AL, Walton AM, Shaw-Kokot J, et al. Patient Reported Symptoms and Quality of Life in Adult Survivors of Acute Leukemia: A Systematic Review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015:E91–E101. doi: 10.1188/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster K, Chivington K, Shonk C, et al. Measuring quality of life (QOL) among patients with leukemia: The Functional Assessment of Cancer-Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu) Quality of Life Research. 2002;11(7):678. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG for the PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses: the PRIMSA statement criteria. [Accessed on July 13, 2014];BMJ. 2009 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. from http://www.prisma-statement.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendoza T, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, Morrissey M, Johnson BA, Wendt JK, Huber SL. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85(5):1186–1196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Wesbster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Management. 1997;13(2):63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale: development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer: The M. D. Anderson Symptom. Inventory Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634–1646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaronson N, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alibhai S, O'Neill S, Fisher-Schlombs K, et al. A clinical trial of supervised exercise for adult inpatients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) undergoing induction chemotherapy. Leukemia Research. 2012;36(10):1255–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alibhai S, Leach M, Kermalli H, et al. The impact of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and its treatment on quality of life and functional status in older adults. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2007;64(1):19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alibhai S, Leach M, Kowiger ME, et al. Fatigue in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia: predictors and associations with quality of life and functional status. Leukemia. 2007;21(4):845–848. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Battaglini CB, Hackney AC, Garcia R, et al. The effects of an exercise program in leukemia patients. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2009;8(2):130–138. doi: 10.1177/1534735409334266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efficace F, Cartoni C, Niscola P, et al. Predicting survival in advanced hematologic malignancies: do patient-reported symptoms matter? European Journal of Haematology. 2012;89(5):410–416. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarden M, Adamsen L, Kjeldsen L, et al. The emerging role of exercise and health counseling in patients with acute leukemia undergoing chemotherapy during outpatient management. Leukemia Research. 2013;37(2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shabbir M, O'Neill S, Fisher-Schlombs K, et al. A clinical trial of supervised exercise for adult inpatient with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) undergoing induction chemotherapy. Leukemia Research. 2012;36(10):1255–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohamedali H, Breunis H, Timilshina, et al. Older age is associated with similar quality of life and physical function compared to younger age during intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia Research. 2012;36(10):1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliva E, Nobile F, Alimena G, et al. Quality of life in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: patients may be more accurate than physicians. Haematologica. 2011;96(5):696–702. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.036715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearce M, Coan A, Herndon J, III, et al. Unmet spiritual care needs impact emotional and spiritual well-being in advanced cancer patients. Supportive Care Cancer. 2012;20(10):2269–2276. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Persson L, Larsson G, Ohlsson O, et al. Acute leukaemia or highly malignant lymphoma patients' quality of life over two years: A pilot study. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2001;10(1):36–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schumacher A, Kessler T, Buchner T, et al. Quality of life in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving intensive and prolonged chemotherapy—A longitudinal study. Leukemia. 1998;12(4):586–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cella D, Jensen SE, Webster K, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in leukemia: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy--Leukemia (FACT-Leu) questionnaire. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41(10):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cella D. Measuring quality of life in palliative care. Seminars in Oncology. 1995;22(2 Suppl 3):73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrell BR, Hassey Dow K, Grant M. Measurement of the QOL in cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research. 1995;4(6):523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Quality of Life Research. 2002;11(3):193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang PH, Lai YH, Shun SC, et al. Effects of a walking intervention on fatigue-experiences of hospitalized acute myelogenous leukemia patients undergoing chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35(5):524–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klepin H, Danhauer S, Tooze J, et al. Exericse for older adult inpatients with acute myelogenous leukemia: A pilot study. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2011;2(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryant AL, Walton AM, Phillips B. Cancer-Related Fatigue: Scientific Progress has been made in 40 Years. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2015;19(2):137–139. doi: 10.1188/15.CJON.137-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]