Abstract

Background

Treatment for unstable angina (UA) or non-STEMI (NSTEMI) is aimed at plaque stabilization to prevent infarction. Two treatment strategies are: (1) invasive (i.e., cardiac catheterization laboratory < 24 hours after admission), or (2) selectively invasive (i.e., medications with cardiac catheterization laboratory > 24 hours for recurrent symptoms). However, it is not known if the frequency of transient myocardial ischemia (TMI), or complications during hospitalization varies by treatment.

Purpose

We examine; (1) occurrence of TMI in UA/NSTEMI, (2) compare frequency of TMI by treatment pathway and (3) determine predictors of in-hospital complications (i.e., death, MI, pulmonary edema, shock, arrhythmia w/intervention).

Method

Hospitalized patients with CAD (i.e., history of MI, PCI/stent, CABG, > 50% lesion via angiogram, or positive troponin) were recruited and 12-lead ECG Holter initiated. Clinicians, blinded to Holter data, decided treatment strategy; off-line analysis was done post discharge. TMI was defined as > 1 mm ST-segment ↑ or ↓, in > 1 ECG lead, > 1 minute.

Results

Of 291 patients, 91% were white, 66% male, 44% prior MI, and 59% prior PCI/stent or CABG. Treatment pathway was early in 123 (42%), and selective in 168 (58%). Forty-nine (17%) had TMI; 19 (15%) early invasive, 30 (18%) selective (p = 0.637). Acute MI after admission was higher in patients with TMI regardless of treatment strategy (early no TMI 4% vs yes TMI 21%; p = 0.020; selective no TMI 1% vs yes TMI 13%; p = .0004). Predictors of major in-hospital complication were TMI (OR 9.9; 95% CI, 3.84 to 25.78), and early invasive (OR 3.5; 95% CI, 1.23 to 10.20).

Conclusions

In UA/NSTEMI patients treated with contemporary therapies, TMI in not uncommon. The presence of TMI and early invasive treatment are predictors of major in-hospital complications.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is an umbrella term used to describe three specific diagnoses: unstable angina (UA), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Of these, UA and NSTEMI represent the largest proportion of ACS patients (two-thirds), and both are clinically challenging to diagnose since these patients often have atypical symptoms, and non-specific or no electrocardiographic (ECG) changes.1, 2 While biomarkers (i.e., troponin, CK-MB) are the gold standard for identifying myocardial infarction, these biomarkers are not sensitive to transient myocardial ischemia seen among ACS patients with UA, and may not become positive in patients with NSTEMI for several hours after symptom onset.3 Therefore, the treatment goal in UA/NSTEMI is timely identification of myocardial ischemia, or pre-infarction so that treatment(s) to optimize blood flow to the myocardium can be administered immediately. Because nurses provide ongoing assessment of patients for symptoms and electrocardiographic (ECG) changes associated with ACS, their role is pivotal in the detection of myocardial ischemia.

Currently, two treatment pathways are used, early invasive, which includes anti-ischemic, antithrombotic, and antiplatelet medications with coronary angiography in fewer than 24 hours after admission, or selectively invasive which include pharmacological management as above and angiography (typically >24 hours after admission) only if a patient fails to respond to intensive medical management (e.g., refractory angina, angina at rest, etc.) or has objective evidence of ongoing ischemia (e.g., dynamic ST-segment changes, positive biomarkers, etc.).3 Data from a number of randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses show that long term outcomes, two to five years, are better in UA\NSTEMI patients when an early invasive strategy is used versus a selectively invasive approach.4–13 While long term outcomes are more favorable when an early invasive approach is used, some of these studies showed that death and MI are higher during the index hospitalization when an early invasive strategy is used, indicating increased hazard for early invasive.9, 14–16 Another important consideration is that cross-over from selectively invasive to invasive (i.e., PCI/stent, or coronary artery bypass graft surgery) is not uncommon.3, 8, 13, 17, 18 These studies show that both strategies have inherent risks/benefits; thus, current recommendations from the ACC/AHA guidelines for management of NSTEMI/UA emphasize the need to carefully risk stratify each patient when choosing the optimal treatment pathway.1, 2 There is a need for additional diagnostic information during hospitalization that might help clinicians decide which patients are responding well to anti-ischemia therapies and which need more aggressive management.

The 12-lead ECG is an important part of risk stratification in UA/NSTEMI because it has advantages over symptoms, which are often unreliable or non-existent,19–25 or biomarkers, since ECG changes may precede the elevation of these blood tests.1, 3 Most commonly, clinicians obtain serial resting 12-lead ECGs, at 15 to 30 minute intervals, which are within guideline recommendations,3 and then apply dual lead continuous bedside ECG monitoring, ideally with ST-segment monitoring software activated,3, 26, 27 in order to expedite prompt detection of dynamic ST-segment changes indicative of ischemia. Several problems exist with these ECG approaches: (1) plaque rupture in ACS is dynamic, with cycles of occlusion and reperfusion, therefore, intermittent (“snap-shot”) ECG’s will miss acute ST-segment changes; (2) typical bedside monitors utilize only two to six ECG leads, rather than the recommended 12-leads, and (3) ST-segment monitoring software is vastly underutilized because it is plagued by a high number of false positive alarms.26–32 Given the challenges clinicians face when risk stratifying UA/NSTEMI patients for early versus selectively invasive treatment, there is a need to reexamine the potential value of continuous 12-lead ECG ST-segment monitoring for detection of ischemia during the initial hospital phase. Continuous ECG information could add to our understanding of how these two treatment strategies evolve during the acute phase of treatment, which could ultimately be used to guide treatment for UA/NSTEMI.

The purpose of this study was three-fold: (1) examine the occurrence of transient myocardial ischemia (TMI), in a group of hospitalized UA/NSTEMI patients treated with contemporary therapy; (2) compare the frequency of TMI by treatment pathway, early versus selectively invasive, and (3) determine if demographic, clinical history, treatment strategy, or TMI predict serious in-hospital complications.

Methods & Materials

The COMPARE study (R21 NR-011202, PI: MMP), described previously,33 was a prospective observational study designed to examine the frequency and consequences of TMI in hospitalized patients with UA/NSTEMI. In the COMPARE study, early invasive was defined as cardiac catheterization ≤ 24 hours after admission, with PCI/stent, or CABG if indicated. Selectively invasive was defined as pharmacological therapies, with cardiac catheterization >24 hours after hospital admission for failed aggressive medical treatment, as indicated by recurrent symptoms, ECG changes or positive stress test. Prior to recruitment and enrollment, approval from local institutional review boards was obtained, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Sample/Settings

Inclusion criteria were: (1) admitted for treatment of UA, NSTEMI, or suspected ACS and (2) English speaking. Patients were excluded if, admitted for STEMI, were comatose, had a major psychiatric disorder, isolation precautions, or left bundle branch block or ventricular pacing because these conditions distort the ST-segment, making it difficult to reliably interpret the ECG for ischemia.27

During the hours of 7 am to 5 pm, Monday through Friday, any patient presenting to the hospital for symptoms suggestive of ACS were invited to participate. Reported in this paper are only those with confirmed coronary artery disease (CAD) defined by: > 50% coronary lesion assessed by angiography, prior MI (i.e., medical record, or Q-waves on 12-lead ECG), positive biomarkers (i.e., troponin, CK-MB), or prior diagnosis of CAD (i.e., medical record, stent, CABG).

Data were collected at three private hospitals, two in Northern Nevada, one 380 beds the other 720 beds, and one in Northern California, with 366 beds; each hospital had well-developed cardiac service lines, board certified cardiologists, and a full range of invasive and non-invasive treatments (e.g., cardiac catheterization, operating rooms, cardiac rehabilitation, etc.).

12-Lead Holter Electrocardiographic Data

A 12-lead ECG Holter recorder (Mortara Instruments, Milwaukee, WI) was applied to patients meeting inclusion criteria. The Holter recorder was a “black box,” hence, data were not available to clinicians for decision making and there were no alarms generated: off-line analysis (described below) was conducted after hospital discharge. To ensure high quality ECG data, the skin on the torso was carefully prepped to remove any dirt, oils or creams that might interfere with signal quality, chest hair was cautiously clipped if necessary, radiolucent ECG electrodes were applied in the Mason-Likar limb lead configuration so as to not interfere with X-rays, and template ECGs were obtained with patients assuming supine, right- and left-side lying positions for use during off-line analysis to identify false positive ECGs due to positional changes.34–36 The ECG Holter recorder remained in place until the patient was discharged. All patients were maintained on the hospital’s bedside ECG monitor (five or six lead system) as per the hospital protocol. The research assistant made frequent rounds during the day to maintain accurate placement of the ECG electrodes/lead wires and reapply any that had fallen off or been taken off for procedures (e.g., cardiac catheterization, echocardiogram, X-ray, etc.). The research assistant also retrieved demographic, clinical and outcome data from the electronic health record.

ECG Ischemia Analysis

The 12-lead ECG Holter data were downloaded to a research computer and analyzed after hospital discharge using H-Scribe Analysis System (Mortara Instruments, Milwaukee, WI). TMI was defined as ST deviation (elevation or depression) ≥ 100 microvolts in ≥ 2 ECG leads ≥ 60 seconds.27 The H-Scribe software displays 24 hours of ECG tracings into trended data for easy inspection, and semi-automatically analyzes and codes ischemic events. While the H-Scribe provides semi-automated analysis, all of the ECG data were manually over read by the principal investigator (MMP) who was blinded to treatment group and clinical outcomes. In cases where there were questions about whether TMI was present/absent, two co-investigators (MGC, TMK) reviewed the ECG data and consensus was reached.

Outcome Measures

The six in-hospital complications, identified from EHR review, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of Six in-hospital complications identified from review of the electronic health record following hospital discharge.

| 1. Arrhythmia requiring intervention with antiarrhythmic drugs, defibrillation, pacemaker |

| 2. Hemodynamic compromise requiring intervention with drugs, intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation, pacemaker |

| 3. New onset pulmonary edema during hospitalization requiring treatment with diuretics |

| 4. Unplanned transfer from the telemetry unit to coronary care unit (CCU) due to acute complications, including unrelieved chest pain, ECG changes, acute heart failure, arrhythmias, hemodynamic compromise, or cardiac arrest |

| 5. Cardiovascular related death |

6. MI after hospital admission:51, 52

|

ECG = electrocardiogram

MI = myocardial infarction

CK-MB = creatine kinase – myocardium

PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation 1994, 2014). Descriptive statistics were used to report demographic (i.e., age, gender, and ethnicity) and clinical information including medical history (i.e., prior angina, prior MI, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, prior cardiac procedures, and CAD). In addition, descriptive statistics were used to examine procedures performed (i.e., PCI/stent, CABG, treadmill test, and echocardiography), and medications administered. These values are expressed as means ± standard deviation and percentages for the entire sample, and by treatment group. Categorical variables were analyzed with χ2 analyses, with two sided Fisher’s Exact Test p-values reported. Two-tailed unpaired Student t-tests were used to compare continuous variables. A p value of < 0.05 was adopted as the critical value to determine whether differences between the two groups were statistically significant.

The occurrence of each complication was examined initially by χ2 analyses. To determine if patients with TMI compared to patients without TMI had more major in-hospital complications, a multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted. The independent predictors entered into the model were covariates known to increase adverse events in ACS patients including: age, gender, ethnicity, history of angina, MI, PCI, CABG, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, as well as treatment group (early or selective), and presence of TMI detected with 12-lead ECG Holter. The multiple logistic regression analysis examined the odds afforded by each covariate for the occurrence of the dependent variable, any adverse in-hospital complication. Odds ratios, and adjusted odds ratios, with 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results

Of the 488 total subjects enrolled, 174 (36%) did not have confirmed CAD, and 23 (5%) had left BBB, or a ventricular pacemaker and therefore were excluded; hence, the final sample was 291 patients. The mean time from hospital presentation to enrollment was 6 ± 5 hours, and mean monitoring time was 28 ± 20 hours. Of the 291 patients, 123 (42%) were treated with an early invasive strategy and 168 (58%) with a selectively invasive strategy. Sample characteristics were typical of those with CAD with regards to age (65 ± 12 years), and gender (male, 66%), and did not differ by treatment strategy (Table 2). Of the mostly white sample (91%), a higher proportion of ethnic minorities were in the selectively invasive group, 12% vs 5%; p = 0.04. Patients with a history of prior angina were more likely to be treated with an early invasive approach (49% versus 24%; p = 0.001), whereas those with prior CAD (56% versus 81%; p = 0.001), MI (32% versus 53%; p = 0.001), or CABG (15% versus 31%; p = 0.001) were more often treated with a selectively invasive strategy. Prior PCI was equivalent by group. The only risk factor that differed by treatment group was diabetes (23% early versus 38% selective; p = 0.007). While the majority of patients were admitted to the telemetry unit (85%), a higher proportion of early invasive patients were admitted to the coronary care unit (18% versus 7%; p = 0.006). There were no differences with regards to prescribed medication by treatment group, except for beta blocker (87% early versus 71% selective; p = 0.002). Hospital length of stay was longer in the early invasive group 88 ± 92 hours versus 63 ± 62 hours; p = 0.018.

Table 2.

Demographic, Clinical History and Hospital Treatment for All Subjects and By Group

| Characteristics | Study Sample n = 291 |

Early Invasive n = 123 (42%) |

Selectively Invasive n = 168 (58%) |

p-Value Early vs Selectively Invasive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age (mean ± SD, in years) | 65 ± 12 | 63 ± 11 | 66 ± 12 | 0.062 |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 192 (66) | 87 (71) | 105 (63) | 0.169 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 6 (2) | 0 | 6 (4) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.046 |

| Black | 10 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | |

| Pacific Islander | 5 (2) | 0 | 5 (3) | |

| White | 265 (91) | 117 (95) | 148 (88) | |

|

| ||||

| Race Comparing Non-White to White | 265 (91) | 117 (95) | 148 (88) | 0.040* |

|

| ||||

| Cardiac history | ||||

|

| ||||

| Prior angina | 101 (35) | 60 (49) | 41 (24) | 0.001** |

|

| ||||

| Prior coronary artery disease | 205 (70) | 69 (56) | 136 (81) | 0.001** |

|

| ||||

| Prior acute myocardial infarction | 127 (44) | 39 (32) | 88 (53) | 0.001** |

|

| ||||

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 126 (43) | 51 (42) | 75 (45) | 0.633 |

|

| ||||

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft | 70 (24) | 18 (15) | 52 (31) | 0.001** |

|

| ||||

| Risk factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Current Smoker | 65 (22) | 34 (28) | 31 (19) | 0.066 |

|

| ||||

| High cholesterol | 209 (72) | 87 (71) | 122 (73) | 0.792 |

|

| ||||

| High blood pressure | 212 (73) | 83 (68) | 129 (77) | 0.084 |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes | 91 (31) | 28 (23) | 63 (38) | 0.007* |

|

| ||||

| Admission unit | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cardiac Telemetry | 244 (85) | 100 (81) | 144 (86) | 0.336 |

| Cardiac Intensive Care | 34 (12) | 22 (18) | 12 (7) | 0.006* |

|

| ||||

| Cardiac medications | ||||

|

| ||||

| Nitrate | 171 (59) | 79 (64) | 92 (55) | 0.118 |

|

| ||||

| Beta blocker | 227 (78) | 107 (87) | 120 (71) | 0.002* |

|

| ||||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 135 (46) | 63 (51) | 72 (43) | 0.191 |

|

| ||||

| Antiplatelet | 275 (95) | 118 (96) | 157 (94) | 0.441 |

|

| ||||

| Aspirin | 272 (94) | 118 (96) | 154 (92) | 0.159 |

|

| ||||

| Antithrombin | 209 (72) | 94 (76) | 115 (69) | 0.148 |

|

| ||||

| Lipid lowering | 224 (77) | 101 (82) | 123 (73) | 0.091 |

|

| ||||

| Hospital Length of Stay | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hours | 75 ± 82 | 88 ± 92 | 63 ± 62 | 0.018* |

Early Invasive = pharmacological therapies, and cardiac catheterization ≤ 24 hours of hospital admission). Selectively Invasive = pharmacological therapies, with cardiac catheterization > 24 hours after hospital admission for failed aggressive medical treatment, as indicated by recurrent symptoms, ECG changes (hospital monitor or ordered 12-lead) or positive stress test.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001

Frequency of Transient Myocardial Ischemia by Treatment Strategy

During 8,140 hours of 12-lead ECG Holter monitoring in 291 patients, 49 (17%) had 109 total TMI events. Of the 49 patients with TMI events, 19 (15%) were treated with early invasive, and 30 (18%) with selectively invasive (p = 0.637). The mean number of TMI events was 2 ± 1 (range one to six), and was equivalent by treatment group (p = 0.269). Of the 49 patients, only 16 (33%) experienced symptoms during TMI. A higher number of patients in the early invasive group complained of symptoms (early 10/19 [53%] versus selective 6/30 [20%]; p 0.028). Figure 1 illustrates transient ischemia in a patient treated with a selectively invasive treatment strategy.

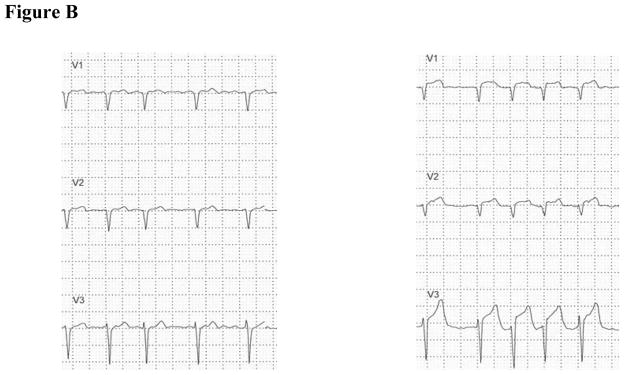

Figure 1.

Illustrates a patient treated with a selectively invasive strategy. Top figure A shows an ST-segment trend (Y-axis electrocardiographic (ECG) leads; X-axis time). This trend was recorded in a 67 year old male presenting to the emergency department at 0345 with pain between his shoulder blades and in his right arm. His cardiac history included paroxysmal atrial fibrillation treated with metoprolol and Coumadin, the latter was discontinued for unknown reasons one month prior. His initial troponin I was normal and his 12-lead ECG was unremarkable for acute ischemia. A CT scan ruled out aortic aneurysm, and he was admitted to the telemetry unit for further workup.

At 0300 (23 hours post admission) abrupt ST elevation is seen in leads V1–V4, and concomitant ST depression in leads V6, I, II, aVF and III. At 0345 the patient complained of back and right arm pain. The nurse gave the patient a sublingual nitroglycerin, IV morphine and obtained a 12-lead ECG. The hospital 12-lead ECG was obtained after the ST changes resolved; hence ischemia was not diagnosed. The patient went back to sleep. At 0555 the patient contacted the nurse complaining of 10/10 chest pain in his back and both arms. A hospital 12-lead ECG obtained by the nurse showed ST elevation in leads V2 and V3. The cardiologist was phoned and the patient was taken urgently to the cardiac catheterization laboratory where a stent was placed in the left anterior descending coronary artery. Of note, are the small ST segment changes during the day at 1320, 1800, and 2345, likely indicating acute but brief coronary occlusion followed by reperfusion.

Figure A. ST-segment Trend with time on X-axis and ECG Leads on Y axis.

Figure B. Left figure shows leads V1 to V3 (#1 in above figure), was obtained before transient myocardial ischemia. Right figure shows leads V1 to V3 (#2 in above figure), was obtained during transient myocardial ischemia and illustrates ST elevation indicative of complete coronary occlusion.

Major In-Hospital Complications

Of the 291 patients, 26 (9%) experienced a major in-hospital complication. Regardless of treatment strategy, major in-hospital complications were higher in those with TMI (5% no TMI versus 31% with TMI; p < .001). Of the 26 patients who experienced a major in-hospital complication, a higher proportion were in the early invasive group (14% early versus 5% selective; p = 0.021). Table 3 shows comparisons of major in-hospital complications by treatment strategy, and absence/presence of TMI. No patient died. Acute MI after hospital admission was higher in patients who experienced TMI regardless of treatment strategy (early no TMI 4% versus yes TMI 21%; p = 0.020; selective no TMI 1% versus yes TMI 13%; p = 0.004). Acute pulmonary edema occurred more often in early invasive patients with TMI (no TMI 0 patients versus 16% yes TMI; p = 0.003), however this was not different in the selective group. Among the early invasive group, a higher proportion with TMI were transferred from telemetry to the CCU due to acute complications (no TMI 2% versus yes TMI 32%; p = 0.001). While more patients with TMI in the selectively invasive group were transferred from telemetry to CCU this was not statistically different (no TMI 1% versus yes TMI 7%; p = 0.083). When any major in-hospital complications was combined into one variable, patients with TMI, regardless of treatment strategy, had more complications (early no TMI 8% versus yes TMI 47%; p = 0.001; selective no TMI 2% versus yes TMI 20%; p = 0.001).

Table 3.

Comparison of major in-hospital complications by treatment strategy, with groups divided further by transient myocardial ischemia (TMI) absent/present (n = 291).

| Complication | Early Invasive (n = 123) n (%) |

Selectively Invasive (n = 168) n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No TMI 104 (85) |

Yes TMI 19 (15) |

p-value | No TMI 138 (82) |

Yes TMI 30 (18) |

p-value | |

| Arrhythmia with intervention | 5 (5) | 1 (5) | 1.000 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemodynamic Compromise | 1 (1) | 1 (5) | 0.268 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary Edema | 0 | 3 (16) | 0.003 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Transfer from Tele to CCU | 2 (2) | 6 (32) | 0.001 | 1 (1) | 2 (7) | 0.083 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MI After Admit | 4 (4) | 4 (21) | 0.020 | 1 (1) | 4 (13) | 0.004 |

| Any Major Complication | 8 (8) | 9 (47) | 0.001 | 3 (2) | 6 (20) | 0.001 |

Two sided Fisher’s Exact Test is reported.

TMI = transient myocardial ischemia; MI = myocardial infarction; CCU = cardiac intensive care unit

Results of the logistic regression analysis examining whether demographic, clinical history, treatment strategy or TMI were predictors of major in-hospital complications are shown in Table 4. Compared to patients without TMI, patients with TMI were 9.9 times more likely to experience a major in-hospital complication (95% CI, 3.84 to 25.78, p=0.001), and patients treated with an early invasive strategy were 3.5 times more likely to have a major in-hospital complication (95% CI, 1.23 to 10.20, p=0.019).

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression analysis with any major in-hospital complication used as the dependent variable.

| Variable | B | P-value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.000 | 0.983 | 1.000 | [0.959, 1.042] |

| Gender (male = 0 female = 1) | −0.612 | 0.278 | 0.542 | [0.179, 1.638] |

| History Angina | 0.097 | 0.845 | 1.102 | [0.418, 2.902] |

| History MI | −0.287 | 0.632 | 0.750 | [0.232, 2.427] |

| History PCI | −0.435 | 0.436 | 0.648 | [0.217, 1.935] |

| History CABG | 0.207 | 0.733 | 1.231 | [0.374, 4.052] |

| Hypertension | 0.392 | .483 | 1.480 | [0.495, 4.425] |

| Hypercholesterolemia | −0.575 | 0.267 | 0.563 | [0.204, 1.553] |

| Transient myocardial Ischemia | 2.297 | 0.001* | 9.949 | [3.839, 25.784] |

| Early Invasive Treatment Group | 1.266 | 0.019* | 3.547 | [1.233, 10.204] |

p < 0.05

Discussion

Among hospitalized UA/NSTEMI patients, TMI is not uncommon; occurring in 17%, and its presence is highly predictive of untoward in-hospital complications, particularly MI after admission. This study is unique in that we explore the frequency and consequences of TMI, measured with continuous 12-lead ECG, comparing groups by contemporary treatment pathway (early versus selectively invasive). At the outset of this study, we hypothesized TMI would be higher in the selectively invasive group, thinking reperfusion would not be as complete with medications alone, but found there was no difference in the rate of TMI between the groups. Our data indicate that when combined, major in-hospital complications are more common in patients with TMI, regardless of treatment pathway, but are more frequent among patients treated with an early invasive strategy as compared to those treated with a selectively invasive strategy.

Occurrence of Transient Myocardial Ischemia & Comparison by Treatment Pathway

As mentioned, we found that 17% of our sample had TMI (early 15%; selective 18%), which is similar to prior studies.23–25, 28, 30, 37–42 Importantly, most of these prior studies are dated, thus one could argue, may not represent patients treated with present-day therapies. However, we show that this pathology is still occurring in a relatively high number of UA/NSTEMI patients despite advances in ACS treatment modalities.

Similar to previous reports we found that only a third of the patients with TMI complained of chest pain or an angina equivalent.22, 24, 25, 28, 36, 37, 40, 41, 43 While this is not a new finding, our study underscores the problem of symptoms as a reliable indicator of myocardial ischemia. It is worth noting that a criterion for failing intensive medical management in patients treated with a selectively invasive strategy is refractory angina, or angina at rest. Given that the vast majority of patients with TMI do not experience symptoms during ECG detected ischemia, identification of failed medical therapy is very likely to be missed using symptoms alone.

Interestingly, we found that patients treated with an early invasive approach and who had TMI were more likely to experience symptoms as compared to the selectively invasive TMI group. This might suggest ischemic burden was higher in the early invasive group. In a prior study, we reported that patients were more likely to experience symptoms during TMI as the magnitude (microvolts) of ST-segment changes increased.37 Our data highlight the value of continuously recorded 12-lead ECG’s as a way to identify transient, mostly silent, ischemia in NSTEMI/UA patients who represent the largest portion of patients presenting for ACS.

Major In-Hospital Complication Rates and Predictor of Major In-Hospital Complication

Major in-hospital complications were significantly higher in patients with TMI as compared to those without TMI regardless of treatment strategy group. When complications were assessed by group, patients treated with an early invasive strategy, and who had TMI, were more likely to have MI after admission, acute pulmonary edema, and require transfer from the telemetry unit to the CCU due to acute clinical changes. Among the selectively invasive group, those with TMI were more likely to experience MI after admission, and there was only a trend for those with TMI to be transferred from the telemetry unit to the CCU due to acute clinical changes. Our findings are in agreement with others showing the relationship of ECG detected TMI and untoward in-hospital complications. 19, 24, 25, 40, 43 Our findings are unique in that we examine not only the influence of TMI on in-hospital outcomes, but further assess this pathology by treatment group. Our finding of higher complication rates among early invasive patients is in contrast to a meta-analysis of a large number of randomized clinical trials with large sample sizes comparing early versus selectively invasive treatment, which showed a non-significant trend for higher rates for non-fatal MI among patient treated with an early invasive strategy.11 A possible explanation for this may be how MI after admission was defined in our study compared to the aforementioned clinical trials, dated from 1994 to 2005, which are prior to high sensitivity troponin tests.

When controlling for known risk factors, logistic regression analysis showed two predictors of major in-hospital complication were; early invasive treatment (OR 3.5) and TMI (OR 9.9). The latter reiterates the sensitivity of TMI to identify high risk patients that might benefit from more aggressive anti-ischemia therapies.

Limitations

Convenience sampling did not yield all consecutive patients; thus patients were missed. This could be important because we examined the group by treatment pathway (early versus selective). It is possible patients presenting on the weekend or at night are more likely to have selective treatment due to cardiac catheterization laboratory availability and staffing. While the mean time from hospital presentation to initiation of 12-lead ECG Holter was six hours, it is possible we missed TMI during the early course of hospitalization, which would underestimate the rate of TMI. This was a hospital based study, therefore, long term outcomes cannot be examined.

Conclusions

The data from this study supports three conclusions: that nearly 20% of hospitalized UA/NSTEMI patients had TMI, that the frequency of TMI between treatment pathway (early vs selectively invasive) was not different and that major in-hospital complications were significantly higher in patients with TMI and early invasive treatment. An important strength of this study was that it included UA/NSTEMI patients treated with contemporary therapies. Transient myocardial ischemia detected with continuous 12-lead ECG is a significant contributor to major in-hospital complications and should be carefully assessed for in this patient population. This finding is not necessarily novel. However, there has been marked paucity of studies on this topic in the past decade – why? Underutilization of ST-segment monitoring software for detection of TMI is multifaceted including; physician factors (lack of interest or unaware of current recommendations for ST-segment monitoring),31, 32 nurse factors (lack of knowledge, skill and ability),29, 44, 45 and the high number of false positive alarms.46 The value of assessing for dynamic, often clinically silent myocardial ischemia should not be ignored because of these issues, rather each of these challenges should be further explored and strategies and interventions developed to address each. For example, guidance from the American Association of Critical Care Nurses’ Alarm Management recommendations including: providing proper skin preparation for ECG electrodes, change ECG electrodes daily and customize alarm parameters and levels on ECG monitors.47 Additionally, several quality assurance projects have shown that educational programs improve nurses knowledge and use of ST-segment monitoring.48–50 This technology has the potential to identify high risk patients requiring treatment adjustments. Finally, while we highlight the usefulness of ECG monitoring for detection of TMI, this software might also be useful for ruling out cardiac pathology in patients with symptoms suggestive of ACS, in which there is not a cardiac cause.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grant R21NR011202 (PI - MMP) provided by the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no relationships to disclose with business or industry related to planning, executing, and/or publishing this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- 1.Khera S, Kolte D, Aronow WS, Palaniswamy C, Subramanian KS, Hashim T, Mujib M, Jain D, Paudel R, Ahmed A, Frishman WH, Bhatt DL, Panza JA, Fonarow GC. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the United States: contemporary trends in incidence, utilization of the early invasive strategy, and in-hospital outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB C. American Heart Association Statistics, and S. Stroke Statistics. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, Jr, Jaffe AS, Jneid H, Kelly RF, Kontos MC, Levine GN, Liebson PR, Mukherjee D, Peterson ED, Sabatine MS, Smalling RW, Zieman SJ. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, Vicari R, Frey MJ, Lakkis N, Neumann FJ, Robertson DH, DeLucca PT, DiBattiste PM, Gibson CM, Braunwald E. Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(25):1879–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox KA, Clayton TC, Damman P, Pocock SJ, de Winter RJ, Tijssen JG, Lagerqvist B, Wallentin L, Collaboration FIR. Long-term outcome of a routine versus selective invasive strategy in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(22):2435–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox KA, Goodman SG, Klein W, Brieger D, Steg PG, Dabbous O, Avezum A. Management of acute coronary syndromes. Variations in practice and outcome; findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Eur Heart J. 2002;23(15):1177–89. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox KA, Poole-Wilson P, Clayton TC, Henderson RA, Shaw TR, Wheatley DJ, Knight R, Pocock SJ. 5-year outcome of an interventional strategy in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):914–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullough PA, O’Neill WW, Graham M, Stomel RJ, Rogers F, David S, Farhat A, Kazlauskaite R, Al-Zagoum M, Grines CL. A prospective randomized trial of triage angiography in acute coronary syndromes ineligible for thrombolytic therapy. Results of the medicine versus angiography in thrombolytic exclusion (MATE) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(3):596–605. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta SR, Cannon CP, Fox KA, Wallentin L, Boden WE, Spacek R, Widimsky P, McCullough PA, Hunt D, Braunwald E, Yusuf S. Routine vs selective invasive strategies in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. Jama. 2005;293(23):2908–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Pogatsa-Murray G, Mehilli J, Bollwein H, Bestehorn HP, Schmitt C, Seyfarth M, Dirschinger J, Schomig A. Evaluation of prolonged antithrombotic pretreatment (“cooling-off” strategy) before intervention in patients with unstable coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1593–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Donoghue M, Boden WE, Braunwald E, Cannon CP, Clayton TC, de Winter RJ, Fox KA, Lagerqvist B, McCullough PA, Murphy SA, Spacek R, Swahn E, Wallentin L, Windhausen F, Sabatine MS. Early invasive vs conservative treatment strategies in women and men with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(1):71–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spacek R, Widimsky P, Straka Z, Jiresova E, Dvorak J, Polasek R, Karel I, Jirmar R, Lisa L, Budesinsky T, Malek F, Stanka P. Value of first day angiography/angioplasty in evolving Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: an open multicenter randomized trial. The VINO Study. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(3):230–8. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.TIMI. Effects of tissue plasminogen activator and a comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Results of the TIMI IIIB Trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Ischemia. Circulation. 1994;89(4):1545–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoenig MR, Doust JA, Aroney CN, Scott IA. Early invasive versus conservative strategies for unstable angina & non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the stent era. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004815. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004815.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charytan DM, Wallentin L, Lagerqvist B, Spacek R, De Winter RJ, Stern NM, Braunwald E, Cannon CP, Choudhry NK. Early angiography in patients with chronic kidney disease: a collaborative systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1032–43. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05551008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meine TJ, Roe MT, Chen AY, Patel MR, Washam JB, Ohman EM, Peacock WF, Pollack CV, Jr, Gibler WB, Peterson ED, Investigators C. Association of intravenous morphine use and outcomes in acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. Am Heart J. 2005;149(6):1043–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Winter RJ, Windhausen F, Cornel JH, Dunselman PH, Janus CL, Bendermacher PE, Michels HR, Sanders GT, Tijssen JG, Verheugt FW. Early invasive versus selectively invasive management for acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1095–104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desideri A, Fioretti PM, Cortigiani L, Trocino G, Astarita C, Gregori D, Bax J, Velasco J, Celegon L, Bigi R, Pirelli S, Picano E. Pre-discharge stress echocardiography and exercise ECG for risk stratification after uncomplicated acute myocardial infarction: results of the COSTAMI-II (cost of strategies after myocardial infarction) trial. Heart. 2005;91(2):146–51. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.026849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akkerhuis KM, Klootwijk PA, Lindeboom W, Umans VA, Meij S, Kint PP, Simoons ML. Recurrent ischaemia during continuous multilead ST-segment monitoring identifies patients with acute coronary syndromes at high risk of adverse cardiac events; meta-analysis of three studies involving 995 patients. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(21):1997–2006. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drew BJ, Funk M. Practice standards for ECG monitoring in hospital settings: executive summary and guide for implementation. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2006;18(2):157–68. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drew BJ, Krucoff MW. Multilead ST-segment monitoring in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a consensus statement for healthcare professionals. ST- Segment Monitoring Practice Guideline International Working Group. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8(6):372–86. quiz 387–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb SO, Weisfeldt ML, Ouyang P, Mellits ED, Gerstenblith G. Silent ischemia as a marker for early unfavorable outcomes in patients with unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(19):1214–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605083141903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klootwijk P, Meij S, von Es GA, Muller EJ, Umans VA, Lenderink T, Simoons ML. Comparison of usefulness of computer assisted continuous 48-h 3-lead with 12-lead ECG ischaemia monitoring for detection and quantitation of ischaemia in patients with unstable angina. Eur Heart J. 1997;18(6):931–40. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelter MM, Adams MG, Drew BJ. Association of transient myocardial ischemia with adverse in-hospital outcomes for angina patients treated in a telemetry unit or a coronary care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2002;11(4):318–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelter MM, Adams MG, Drew BJ. Transient myocardial ischemia is an independent predictor of adverse in-hospital outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated in the telemetry unit. Heart Lung. 2003;32(2):71–8. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2003.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, Kaufman ES, Krucoff MW, Laks MM, Macfarlane PW, Sommargren C, Swiryn S, Van Hare GF. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721–46. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, Kaufman ES, Krucoff MW, Laks MM, Macfarlane PW, Sommargren C, Swiryn S, Van Hare GF. AHA scientific statement: practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20(2):76–106. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drew BJ, Pelter MM, Adams MG, Wung SF, Chou TM, Wolfe CL. 12-lead ST-segment monitoring vs single-lead maximum ST-segment monitoring for detecting ongoing ischemia in patients with unstable coronary syndromes. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(5):355–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Funk M, Winkler CG, May JL, Stephens K, Fennie KP, Rose LL, Turkman YE, Drew BJ. Unnecessary arrhythmia monitoring and underutilization of ischemia and QT interval monitoring in current clinical practice: baseline results of the Practical Use of the Latest Standards for Electrocardiography trial. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krucoff MW, Croll MA, Pope JE, Pieper KS, Kanani PM, Granger CB, Veldkamp RF, Wagner BL, Sawchak ST, Califf RM. Continuously updated 12-lead ST-segment recovery analysis for myocardial infarct artery patency assessment and its correlation with multiple simultaneous early angiographic observations. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71(2):145–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90729-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton JA, Funk M. Survey of use of ST-segment monitoring in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10(1):23–32. quiz 33–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandau KE, Sendelbach S, Frederickson J, Doran K. National survey of cardiologists’ standard of practice for continuous ST-segment monitoring. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(2):112–23. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelter MM, Kozik TM, Loranger DL, Carey MG. A research method for detecting transient myocardial ischemia in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome using continuous ST-segment analysis. J Vis Exp. 2012;(70) doi: 10.3791/50124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams MG, Drew BJ. Body position effects on the ECG: implication for ischemia monitoring. J Electrocardiol. 1997;30(4):285–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(97)80040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drew BJ, Adams MG. Clinical consequences of ST-segment changes caused by body position mimicking transient myocardial ischemia: hazards of ST-segment monitoring? J Electrocardiol. 2001;34(3):261–4. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2001.25431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drew BJ, Wung SF, Adams MG, Pelter MM. Bedside diagnosis of myocardial ischemia with ST-segment monitoring technology: measurement issues for real-time clinical decision making and trial designs. J Electrocardiol. 1998;30(Suppl):157–65. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(98)80067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams MG, Pelter MM, Wung SF, Taylor CA, Drew BJ. Frequency of silent myocardial ischemia with 12-lead ST segment monitoring in the coronary care unit: are there sex-related differences? Heart Lung. 1999;28(2):81–6. doi: 10.1053/hl.1999.v28.a96639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amanullah AM, Lindvall K. Prevalence and significance of transient--predominantly asymptomatic--myocardial ischemia on Holter monitoring in unstable angina pectoris, and correlation with exercise test and thallium-201 myocardial perfusion imaging. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(2):144–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carmo P, Ferreira J, Aguiar C, Ferreira A, Raposo L, Goncalves P, Brito J, Silva A. Does continuous ST-segment monitoring add prognostic information to the TIMI, PURSUIT, and GRACE risk scores? Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2011;16(3):239–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2011.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drew BJ, Adams MG, McEldowney DK, Lau KY, Wung SF, Wolfe CL, Ports TA, Chou TM. Frequency, duration, magnitude, and consequences of myocardial ischemia during intracoronary ultrasonography. Am Heart J. 1997;134(3):474–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drew BJ, Adams MG, Pelter MM, Wung SF. ST segment monitoring with a derived 12-lead electrocardiogram is superior to routine cardiac care unit monitoring. Am J Crit Care. 1996;5(3):198–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drew BJ, Pelter MM, Adams MG. Frequency, characteristics, and clinical significance of transient ST segment elevation in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(12):941–7. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gottlieb SO, Weisfeldt ML, Ouyang P, Mellits ED, Gerstenblith G. Silent ischemia predicts infarction and death during 2 year follow-up of unstable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10(4):756–60. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelter MM, Carey MG, Stephens KE, Anderson H, Yang W. Improving nurses’ ability to identify anatomic location and leads on 12-lead electrocardiograms with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9(4):218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stephens KE, Anderson H, Carey MG, Pelter MM. Interpreting 12-lead electrocardiograms for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: what nurses know. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22(3):186–93. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000267822.81707.c6. quiz 194–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drew BJ, Harris P, Zegre-Hemsey JK, Mammone T, Schindler D, Salas-Boni R, Bai Y, Tinoco A, Ding Q, Hu X. Insights into the problem of alarm fatigue with physiologic monitor devices: a comprehensive observational study of consecutive intensive care unit patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sendelbach S, Jepsen S. AACN Practice Alert Alarm Management. AACN Evidence Based Practice Resources Work Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chronister C. Improving nurses’ knowledge of continuous ST-segment monitoring. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2014;25(2):104–13. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blakeman JR, Sarsfield K, Booker KJ. Nurses’ Practices and Lead Selection in Monitoring for Myocardial Ischemia: An Evidence-Based Quality Improvement Project. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2015;34(4):189–95. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sendelbach S, Wahl S, Anthony A, Shotts P. Stop the Noise: A Quality Improvement Project to Decrease Electrocardiographic Nuisance Alarms. Crit Care Nurse. 2015;35(4):15–22. doi: 10.4037/ccn2015858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]